Abstract

A total of 111 Candida isolates representing 11 species were examined for their respective responses to a Tween 80 opacity test. The strains of Candida albicans and C. tropicalis that were examined produced an opacity response around their colonies at 2 to 3 days postinoculation. A second group of Candida species yielded a halo around their colonies at 8 to 10 days postinoculation. The remaining Candida species did not produce a positive test response through 10 days postinoculation. The strains of C. dubliniensis were easily differentiated from strains of C. albicans by this test. The Tween 80 opacity test is simple and economical to prepare and is easy to interpret.

Various species of Candida have been reported to have lipolytic activity (3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13). Many of the pathogenic Candida species secrete lipolytic enzymes such as esterases (6, 19) and phospholipases (5). The esterase activities of these yeasts were previously demonstrated with the application of the Tween opacity test medium with different Tween compounds (13). Patterns of Tween opacity responses associated with various Candida species and various Tween compounds were suggested as useful tests for distinguishing various Candida species (13).

Recently, the Tween opacity test was demonstrated to be useful for the identification of various dermatophytes (16). In particular, the period of time that a positive Tween opacity test was first observed yielded a significant identification characteristic for the various dermatophytes that were examined.

The objective of the investigation described here was to ascertain the lipolytic activities of various species of Candida that are clinically significant (4, 8, 18) and to demonstrate that their respective temporal responses to Tween opacity are useful adjuncts in their identification.

A total of 110 cultures representing 11 Candida species were examined. The cultures, except for those of Candida dubliniensis, were obtained from stock cultures maintained at room temperature on malt extract agar slants. The cultures of C. dubliniensis were obtained from David Pincus, bioMerieux, Inc., Hazelwood, Mo., and Michael Rinaldi, Fungus Testing Laboratory, University of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio. The latter yeasts were maintained on malt extract agar. The species of Candida that were examined are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Lipolytic activities of various Candida species on a Tween 80 opacity medium

| Species | No. of isolates tested | No. of isolates positive/total no. of isolates tested for the following period of time (Days) opacity first observed:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–3 | 4–7 | 10–12 | ||

| C. albicans | 15 | 15/15 | ||

| C. dubliniensis | 16 | 0/16 | ||

| C. famata | 15 | 0/15 | ||

| C. glabrata | 15 | 0/15 | ||

| C. guilliermondii | 5 | 5/5 | ||

| C. kefyr | 5 | 0/5 | ||

| C. krusei | 10 | 0/10 | ||

| C. lusitaniae | 2 | 0/2 | ||

| C. parapsilosis | 15 | 0/5 | ||

| C. rugosa | 3 | 3/3 | ||

| C. tropicalis | 10 | 10/10 | ||

The identities of the isolates were reconfirmed according to their morphologies on cornmeal agar, their formation of germ tubes in serum, chlamydospore formation, and their assimilation patterns, which were determined with the API ID 32C yeast identification panel after 72 h of incubation at 30°C. The C. dubliniensis strains were identified in my laboratory with the API ID 32C system by using glycine, xylose, α-methyl-d-glucoside, and trehalose as hallmarks for identification (10).

The agar medium (14) was prepared with 10.0 g of Bacto Peptone (BD Biosciences, Sparks, Md.), 5.0 g of NaCl, 0.1 g of CaCl2, 15.0 g of agar, and 1,000 ml of distilled water. After the medium was autoclaved it was cooled to about 50°C and 5 ml of autoclaved Tween 80 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was added. The 90-mm petri dishes were filled with 25 ml of the medium. The final pH of this medium was 6.8. The inoculated agar plates were incubated at 30°C and were examined daily through 10 days. In one experiment, the inoculated agar plates were incubated at 35°C.

Variations of the standard formula of the agar medium were prepared in order to determine their respective effects on the opacity responses with the test organisms. Accordingly, an experiment was performed by omitting the calcium salt. In another experiment, the calcium salt was used at 0.4 g/liter. In other experiments, the medium was prepared with 0.1, 0.8, or 1.0% Tween 80.

Overnight cultures of each isolate grown on Sabouraud agar were transferred to the Tween 80 medium by touching the center of the agar medium with a cotton swab so as to prepare a circular inoculation site about 10 mm in diameter. The tests were performed in triplicate. The presence of a halo (15) around an inoculated site on the Tween medium, viewed with transmitted light, indicated a positive test and indicated that the Candida isolate produced an esterase.

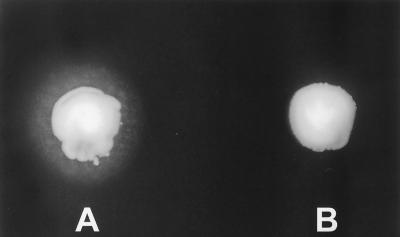

All the strains of C. albicans and C. tropicalis grown on the standard Tween 80 medium produced a halo response that circumscribed their respective inoculated sites from 2 to 3 days postinoculation. The isolates of C. guillermondii and C. rugosa yielded a halo around their inoculated sites at 8 to 10 days postinoculation. The remainder of the Candida species that were examined on the Tween 80 medium produced no halo around their inoculated sites through 10 days of observation. The Tween agar medium yielded similar results when stored at 8°C for 1 month. These results are summarized in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the positive halo response for C. albicans and the negative response for C. dubliniensis at 48 h postinoculation. The API ID 32C system produced a profile number of 7042-1400-15 for 14 strains of C. dubliniensis and a profile number of 7142-1000-15 for 2 strains.

FIG. 1.

Positive halo effect around an inoculation site on Tween 80 opacity test medium with C. albicans (A) and negative response with C. dubliniensis (B) after a 48-h period of incubation at 30°C.

No lipolytic activity occurred when the concentration of Tween 80 in the medium was reduced to 0.1%. The lipolytic Candida species that were examined produced halo responses similar to those produced in the standard medium when the Tween 80 concentrations were 0.8 or 1.0%. None of the Candida species that were examined yielded a halo response when CaCl2 was omitted from the medium.

When the calcium salt concentration was increased to 0.4 g/liter, the isolates of C. guillermondii, C. rugosa, as well as C. parapsilosis yielded halo responses at 3 to 4 days postinoculation. On this modified medium the strains of C. albicans and C. tropicalis produced halo responses like that produced with the standard Tween medium at 2 to 3 days postinoculation.

Previous studies by a Tween opacity test have been applied to detect the lipolytic activities of various bacteria (15) and various species of the mould Chrysosporium (2). Recently, this test was demonstrated to be a useful supplementary test for the identification of various dermatophytes through their respective temporal opacity responses on the Tween 80 opacity medium (16).

The hydrolysis of the Tween opacity medium is associated with the lipolytic enzymes produced by the respective Candida species. Liberated fatty acids bind with the calcium incorporated into the medium. The calcium complex is visible as insoluble crystals around the inoculation site (12).

The use of a Tween 80 medium without the incorporation of a calcium salt did not yield a visible opacity response with the Candida species that were examined in the present investigation. Similar observations were observed previously (13). A wide spectrum of Candida species will yield an opacity response on a calcium salt-free medium containing either Tween 40 or Tween 60 (13). In the present study, it was shown that a few more species of Candida will yield a positive Tween 80 opacity test result when the CaCl2 content is increased to 0.4% than on the standard Tween 80 medium when the CaCl2 content is 0.01%. The standard Tween 80 medium, containing 0.1% CaCl2, however, yields a more differential medium.

The results of the Tween opacity test with the Candida species examined in this investigation were similar when the inoculated plates were incubated at 30 or 35°C. Furthermore, there were no differences with respect to the time of detection or ease of detection.

Recently, the same API ID 32C system profiles for the C. dubliniensis strains examined in this investigation were reported (10).

The present investigation is the first to demonstrate two temporal responses of various Candida species with an opacity effect that can visually be observed on Tween 80 medium. Thus, some of the Candida species that were examined produced a halo response around various colonies within a period of 1 to 3 days postinoculation. A second group of species of Candida produced a halo around their colonies at 8 to 10 days postinoculation. A larger group of Candida species did not yield a Tween 80 opacity response through 10 days postinoculation.

C. dubliniensis is a yeast associated with oral candidiasis (17) as well as candidiasis at other clinical sites (10). This yeast has shared phenotypic similarities with C. albicans (4), and thus, C. dubliniesis isolates may have been misidentified as C. albicans in the past (1, 4). Although growth at 42°C has been used to differentiate these two yeasts, some strains of C. dubliniensis may exhibit either poor (17) or good (14) growth at 42°C. Hybridization methods for the identification of these two yeasts are considered labor-intensive and expensive to perform (10).

The Tween opacity test described in the present report permitted the clear differentiation of the strains of C. albicans from the strains of C. dubliniensis within 3 days of incubation on the Tween 80 medium. Thus, the Tween 80 opacity test medium lends itself to an excellent means of differentiation of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis.

In summary, the Tween opacity test, as described in this report, appears to be a useful adjunct that complements the standard morphologic and physiological tests that are used to identify various species of Candida (18). This test will be especially useful for the differentiation of C. albicans from C. dubliniensis. The test medium is simple and economical to prepare and is easy to interpret.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brandt M E, Harrison L H, Pass M, Sofair A N, Huie S, Li R, Morrison C J, Warnock D W, Hajjeh R A. Candida dubliniensis fungemia: the first four cases in North America. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:46–49. doi: 10.3201/eid0601.000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calvo R M, Calvo M A, Larrondo J. Enzyme activities in Chrysosporium strains. Mycopathologia. 1991;116:177–179. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chattaway F W, Odds F C, Barlow A J E. An examination of the production of hydrolytic enzymes and toxins by pathogenic strains of Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1971;67:255–263. doi: 10.1099/00221287-67-3-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman D C, Rinaldi M G, Haynes K A, Rex J N, Summerbell R C, Anaisse E J, Li A, Sullivan D J. Importance of Candida species other than Candida albicans as opportunistic pathogens. Med Mycol. 1998;36(Suppl. 1):156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghannoun M A. Potential role of phospholipase in virulence and fungal pathogenesis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:122–143. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.1.122-143.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomori G. Microscopic histochemistry, principles and practice. 2nd ed. Chicago, Ill: The University of Chicago Press; 1953. Enzymes; pp. 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordillo M A, Obrajors N, Montesinos J L, Valero F, Lafuente F, Sola C. Stability studies and effect of the initial oleic acid concentration on lipase production by Candida rugosa. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;43:38–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00170620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazen K C. New and emerging yeast pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:462–478. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novotny C, Dolezalova L, Lieblova J. Dimorphic growth and lipase production in lipolytic yeasts. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 1994;39:71–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02814534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pincus D H, Coleman D C, Pruitt W R, Padhye A A, Salkin I F, Geimer M, Bassel A, Sullivan D J, Clarke M, Hearn V. Rapid identification of Candida dubliniensis with commercial yeast identification systems. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3533–3539. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3533-3539.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pospisl L, Kabatova A. Lipolytic activity in some Candida strains. Zentbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektkrnkh Hyg Abt 1 Orig. 1976;131:692–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qadripur S A. Die lipolytische AktiviTät von Dermatophyten. Mykosen. 1989;139:352–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudek W. Esterase activity in Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 1978;8:756–769. doi: 10.1128/jcm.8.6.756-759.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoofs A, Odds F C, Colebunders R, Leven M, Goussens H. Use of specialized isolation media for recognition and identification of Candida dubliniensis isolates from HIV-infected patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:296–300. doi: 10.1007/BF01695634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sierra G. A simple method for the detection of lipolytic activity of microorganisms and some observations on the influence of the contact between cells and fatty substrates. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1957;71:15–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02545855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slifkin M, Cumbie R. Evaluation of the Tween opacity test for the identification of dermatophytes. Med Microbiol Lett. 1996;5:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan D, Coleman D. Candida dubliniensis: an emerging opportunistic pathogen. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1997;8:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warren N G, Hazen R C. Candida, Cryptococcus, and other yeasts of medical importance. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 1184–1199. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wills E D. Lipases. Adv Lipid Res. 1965;3:197–240. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4831-9939-9.50012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]