Last year’s Environmental Scan described the profound impact of COVID-19 on nursing and regulation. Although 2022 was armored with the arrival of three vaccines for adults in the US, many people around the country, tragically, continued to suffer and die from COVID-19. Vaccine hesitancy and a particularly virulent variant of the virus, the Delta variant, reminded the nation that the pandemic was far from over. There was an opportunity for optimism, however. Millions of adults across the United States received a COVID-19 vaccine, and this allowed a return to many aspects of pre-pandemic life.

This report is a comprehensive examination of the current state of nursing, healthcare, and regulation in the year 2022, including the continuing impact of COVID-19 on the nursing workforce, nursing education, healthcare delivery, and legislative and policy issues. It is also a look ahead and is intended to assist nursing regulatory bodies, policymakers, and others in strategic planning and preparing for the future. It is based on the most recent statistics, literature, and research related to healthcare and public protection.

The 2022 Environmental Scan, however, is more than a depiction of recent trends and events; it is a story of resiliency. Despite the continued hardships and challenges of the pandemic, the nursing workforce continues to provide high quality care to patients, nursing education programs are using innovative and collaborative methods to educate students, and nursing regulators are behind the scenes providing support and, of course, protecting the public.

The U.S. Nursing Workforce

While it remains to be seen what lasting impacts the COVID-19 pandemic will have on the nursing and regulatory landscapes, one of the most carefully watched is the impact of the pandemic on the nursing workforce. The existing nursing shortages, the aging of the nursing workforce, and the growing “COVID-19 effect” of nurses leaving the profession due to burnout, fear of infection, or vaccine refusal means that millions of additional nurses will be needed by 2030 to fill the global nurse shortage. While the latest available data suggest a subtly changing workforce, the pandemic may have set in motion a tectonic shift in workforce demographics and post-pandemic dynamics that will reverberate over the next several years.

National and State Data

The latest registered nurse (RN), licensed practical nurse (LPN)/licensed vocational nurse (LVN), and advance practice registered nurse (APRN) workforce data show steady RN employment, declining LPN/LVN employment, and growing APRN employment in 2020. The workforce in 2020 was more demographically diverse and representative of the country’s population than in any other year studied.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s (2021) The Future of Nursing 2020–2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity estimates that around 1 million of the U.S.’s oldest nurses could leave the profession within 10 years.

The RN andLPN/LVN Workforce

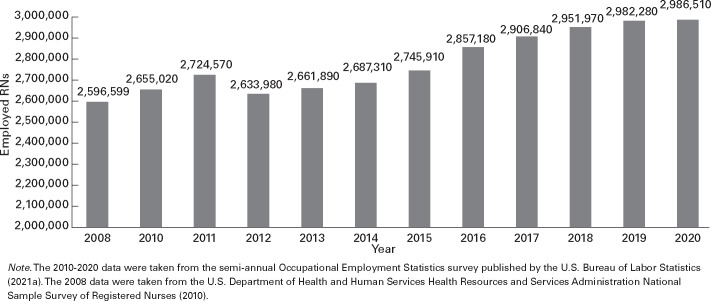

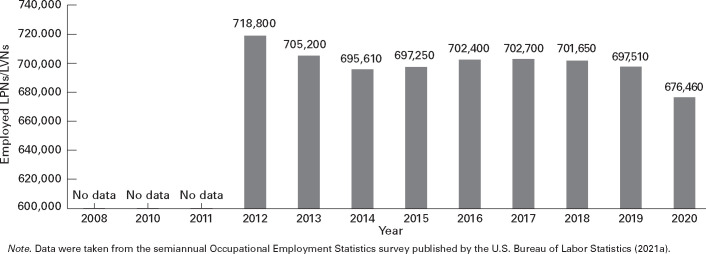

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing’s (NCSBN’s) National Nursing Database tracks the number of U.S. licensed nurses from 57 boards of nursing (BONs) and is updated daily (excluding Michigan). There were 4,317,277 RNs and 918,919 LPNs/LVNs in the United States as of September 30, 2021 (NCSBN, 2021a). The most recent Occupational Employment Statistics data from May 2020 indicate that 2,986,510 RNs and 676,460 LPN/LVNs were employed in the United States (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS], 2021a). Figure 1, Figure 2 illustrate steady RN employment and declining LPN/LVN employment.

Figure 1.

Number of Employed Registered Nurses in the United States, 2008-2020

Figure 2.

Number of Licensed Practical Nurses/Licensed Vocational Nurses in the United States, 2012-2020

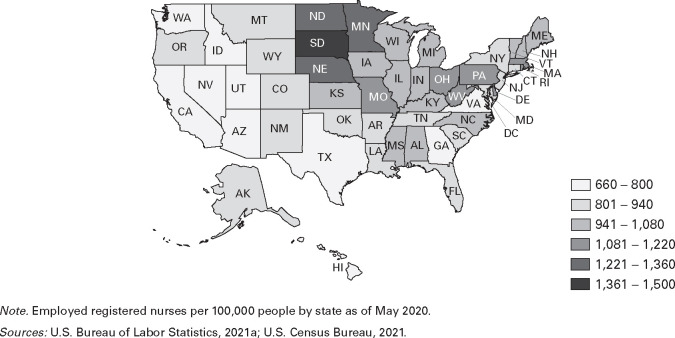

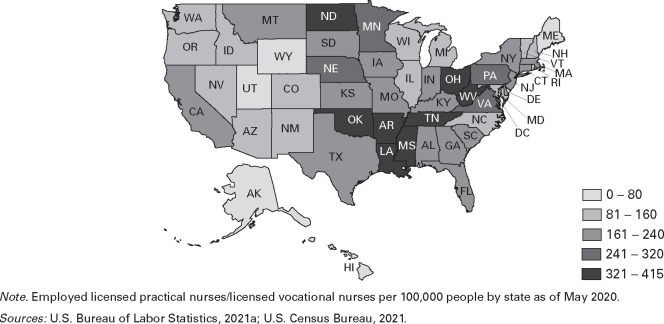

The number of employed RNs per population in each state varies widely across the country, from fewer than 700 nurses per 100,000 people in Georgia to nearly 1,550 nurses per 100,000 in the District of Columbia (Figure 3 ) (BLS, 2021a; U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Utah also has approximately 700 RNs per 100,000 people. Conversely, states in the upper Mid-west—South Dakota (1,481 per 100,000), North Dakota (1,280 per 100,000), and Minnesota (1,241 per 100,000)—have the highest ratios of employed RNs per population. The ratio of employed LPN/LVNs is between 45 and 65 per 100,000 people in Alaska, Utah, and Hawaii and nearly 400 per 100,000 in Louisiana (Figure 4 ).

Figure 3.

Number of Employed Registered Nurses per 100,000 People*

Figure 4.

Number of Employed Licensed Practical Nurses/Licensed Vocational Nurses per 100,000 People

The maps in Figure 3, Figure 4 give a quick state-level snapshot of the supply of employed nurses, noting that there are regional differences within each state that could be different from the overall state-level view. These regional differences within states are often the main concern for individuals involved in studying and monitoring the nursing workforce. For instance, California has one of the lowest employed nurse-to-population ratios; however, within the state, city centers like San Francisco may have very high nurse-to-population ratios, whereas rural areas of the state may have very low nurse-to-population ratios. Within-state regional nurse employment numbers are available from the BLS (2021a).

The APRN Workforce

There are four nursing roles that make up the APRN title: (a) certified nurse practitioners (CNPs), (b) certified nurse midwives (CNMs), (c) clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), and (d) certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs). The APRN workforce is difficult to accurately measure due to variations in state statutes regarding how APRNs are classified; however, the profession continues to grow.

The BLS tracks employment data for the CNP, CNM, and CRNA roles. Currently, the BLS does not independently track employment data for the CNS role. According to the most recent estimates (May 2020), the total number of APRNs employed in the three tracked roles is 271,900 (BLS, 2021c). The BLS expects the role to continue to grow by 45% through the year 2030, adding an estimated 120,000 individuals by that time (BLS, 2021c).

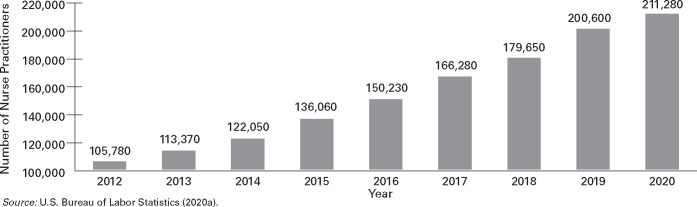

CNPs still make up the most populous APRN role, with 211,280 CNPs employed in the United States according to the most recent data (Figure 5 ). The role has now doubled in size since the BLS began tracking CNPs a decade ago ( BLS, 2021d).

Figure 5.

Number of Certified Nurse Practitioners in the United States, 2012-2020

The number of employed CNMs has increased at a smaller rate, according to the latest data. The BLS estimates the role contains 7,120 individuals as of May 2020, an increase of less than 3% from the previous year (BLS, 2021e).

In contrast to the recent trend, the number of employed CRNAs has decreased according to the most recent data. A total of 41,960 CRNAs were employed in May 2020, representing a decrease of nearly 4% from the previous year (BLS, 2021f). This decrease may be due to the timing of the most recently available BLS data, which show employment numbers from within the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, many health systems had suspended elective surgeries, leading to a furlough of anesthesiology staff, though some were redeployed to intensive and critical care to assist with COVID-19 patients (Relias Media, 2021). As more recent BLS data become available, the CRNA employment trend will bear watching.

The 2020 National Nursing Workforce Survey

Since 2013, NCSBN and the National Forum of State Nursing Workforce Centers have partnered every 2 years to conduct a national sample survey using the Forum’s Nurse Supply Minimum Data Set, a standardized survey tool designed to collect workforce data. The results from the 2020 survey were released in 2021 (Smiley et al., 2021).

Demographics

The workforce in 2020 was more demographically diverse and representative of the country’s population than in any other year in which this study was previously conducted. Overall, the RN workforce is 81% White/Caucasian. In contrast, 72% of the U.S. population identifies as Caucasian (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Although these data indicate that persons of color are not adequately represented in the RN workforce, as younger nurses have entered the workforce, they have introduced greater racial diversity by identifying as an underrepresented minority. Nurses between 19 and 49 years of age comprise 47% of all RNs but account for 49% of RNs who identify as Black/African American and more than 60% of RNs who identify as multiracial, Asian, or Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.

In a pattern similar to that of RNs, younger LPNs/LVNs have introduced more racial diversity to the workforce. However, the racial distribution of the LPN/LVN workforce much more closely matches the racial distribution of the U.S. population than does that of the RN workforce. LPN/LVN licensure requires the lowest level of nursing education and yields a median annual salary that is more than 35% lower than the median income of RNs. Thus, as the workforce ages and the less racially diverse generation of nurses begins to retire, it will be important to monitor whether persons of color begin to account for more of the LPN/LVN workforce than would be representative of the country’s population, as this could indicate barriers in more advanced nursing education that require further exploration.

An additional area that warrants monitoring is the proportion of nurses in the workforce who are working past typical retirement age. Nurses aged 65 years or older account for nearly 20% of each of the RN and LPN/LVN workforces in 2020 (Smiley et al., 2021). In 2017, this same age cohort accounted for 15% of RNs and 13% of LPNs/LVNs (Smiley et al., 2017). During the COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in a high rate of complications and mortality for patients older than 65 years, many nurses are reconsidering how long they plan to remain in the workforce (as the 2020 National Nursing Workforce Survey was conducted in the first months of the pandemic, any demographic shifts of this nature would not have been fully captured).

Although women continue to account for the majority of nurses, the proportion of men licensed as RNs or LPNs/LVNs in the country is increasing. Currently, men account for just under 10% of the RN workforce, which is up from 7% in 2013. The same pattern, though less pronounced, holds true for the proportion of men in the LPN/LVN workforce (8.1%, up from 7.5% in 2015). The increase in the number of men in the overall nursing workforce reflects the improved representation of men among nurses younger than 50 years. Men account for a higher proportion of nurses within every age cohort between 19 and 49 years of age than they account for in the workforce as a whole.

Employment

Data suggest that an average of 83% of all nurses who maintain licensure are employed in nursing; of those, roughly two thirds work full time, 10% work part time, and about 7% work per diem shifts. During the past four reporting periods, there has been a consistent number of RNs and LPNs/LVNs who maintain a nursing license and report working in fields other than nursing. Using weighted sample values, this translates to approximately 200,000 licensees. Additionally, there are approximately 175,000 projected licensees who report being unemployed but are not seeking work as nurses. Still another approximately 15% of unemployed nurses who are seeking nursing employment reported difficulty in finding a nursing position. For nurses who report being unemployed, about half of RNs and roughly 43.3% of LPNs/LVNs cite taking care of their home and family as their reason for not working.

The proportion of nurses reporting a retired nursing employment status is on the rise. In a new survey question for 2020, respondents were asked if they plan to retire in the next 5 years. More than one fifth of all nurses replied positively to the question. The authors note this may be more critical as we face COVID-19 pandemic responses, which may more quickly accelerate the retirement rate due to the increased health risks that COVID-19 places on persons older than 60 years.

Nearly 84% of RNs work only one position in nursing; however, 13.7% reported that they work two positions and 2.4% reported working three positions or more. Nearly 60% of nurses work 32 to 40 hours per week and more than one fifth of nurses work more than 40 hours per week. Similar to RNs, 82.4% of LPNs/LVNs reported being currently employed in only one position, and those who reported working two positions increased from 2017 to 2020. One fifth of LPNs/LVNs reported working 41 to 50 hours in their typical week and roughly 60% reported working 32 to 40 hours.

Hospitals continue to be the primary practice setting for RNs, followed by the ambulatory care setting, home health, and nursing homes. The number of LPNs/LVNs who are working in hospitals has increased since 2017, which corresponds with the decrease of those who reported working in nursing homes or extended care settings. In the recent 2021 NCSBN LPN/LVN Practice Analysis, 48.3% of LPNs/LVNs reported working in long-term facilities, compared to 49.4% in 2018. Similarly, 14.7% of LPNs/LVNs reported working in hospitals in 2021, compared to 13.5% in 2018 (NCSBN, in press; NCSBN, 2019).

Of those nurses who provide direct patient care, more than 90% of the respondents hold the title of staff nurse. Not surprisingly, the title with the least amount of direct patient care is nurse executive. In the specialty area of anesthesia, 94.7% of respondents provide direct patient care; for nurses who report neonatal as their specialty, 91.2% provide direct patient care. Of those nurses reporting geriatric/ gerontology as their specialty area, 45.1% provide direct patient care. Nurses who reported public health (31.0%) and community (26.7%) as specialty areas are provide direct patient care at a proportion lower than that of all other specialties.

Education

In the 2020 survey, the proportion of RNs holding a baccalaureate degree increased for those reporting their highest level of nursing education, but it remained steady for those reporting the degree held when obtaining their first nursing license. The proportion of RNs holding an associate degree when first licensed increased slightly in 2020. This trend had been declining in recent years. When considering only the highest nursing degree earned, the proportion of RNs earning a baccalaureate degree or higher continues to increase, with 65% of nurses currently holding a BSN or higher, although the proportion falls short of the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) 2020 goal of 80% of RNs holding a baccalaureate degree or higher (Institute of Medicine, 2011). The proportion of LPNs/LVNs earning an associate or baccalaureate degree also increased slightly this year, while the proportion of those with a practical/vocational certificate or nursing diploma declined.

There is also evidence that RNs and LPNs/LVNs are continuing their nursing education after obtaining their initial nursing license. Comparing the highest level of nursing education to the educational attainment when first licensed shows that proportionally more RNs hold a baccalaureate or graduate degree than they did at initial licensure. Additionally, proportionally more LPNs/LVNs hold an associate or baccalaureate degree as their highest level of nursing education than at initial licensure.

Experience and Licensure

According to survey respondents, both RNs and LPNs/LVNs are more experienced now than in previous years. The proportion of nurses practicing for 10 years or less has declined, while the proportion of those practicing between 11 and 30 years grew in 2020. As in previous years, most RNs (95%) and LPNs/LVNs (99%) obtained their initial nursing license in the United States.

Salary

The Occupational Outlook Handbook (BLS, 2021b) reported that the median pay for RNs in 2020 was $75,330. The median pay for LPNs /LVNs in 2020 was reported to be $48,820.

Nursing incomes overall have at best remained essentially flat over time, with increases that just barely beat out inflation. Regional income increases in specific states as described in the report may be a good indicator for where employment demand for nurses is high in the country. Of concern are greater-than-average drops in reported median income in specialties related to women and maternal-child health. However, this finding may simply be an indicator that there is less demand in these areas as our population ages.

While telehealth has become a major focus of pandemic healthcare delivery, at the time of this survey, it does not seem that there have been major changes to how nurses use telehealth. It is anticipated that this will change a great deal in the future as our care delivery systems learn how best to utilize nursing services in this new normal.

Health Resources and Services Administration Projections of Supply and Demand for Women’s Health Service Providers

In March 2021, the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis’s report Projections of Supply and Demand for Women’s Health Service Providers: 2018-2030 was released. The key findings of the study are that demand for obstetricians/gynecologists (OB-GYNs) will exceed the national supply, although other women’s health providers are expected to grow at rates that exceed demand. Specifically, based on current utilization patterns, demand for OB-GYNs is projected to exceed supply by 5,170 full-time equivalents (FTEs) by 2030, with supply decreasing from 50,850 to 47,490 (7%).

In contrast, if current usage patterns and new entrant levels remain unchanged, other providers may compensate for this shortage by 2030. Certified nurse midwife (CNM) supply is expected to grow by 32% (from 9,830 to 12,950 FTEs) and women’s health nurse practitioner (NP) supply is projected to grow by 89% (from 10,610 to 20,020 FTEs) while demand is projected to grow by 4% (from 10,610 to 11,050 FTEs) (National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, 2021).

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Future of Nursing Report

In 2021, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released their newest report, The Future of Nursing 2020–2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity. The report estimates that up to 1 million of the U.S. workforce’s oldest nurses could leave the profession within the next 10 years. This loss will be mitigated by more than 1 million nurses anticipated to join the workforce in that same time frame, as well as the continued immigration of internationally educated nurses, which the report estimates may ultimately comprise between 8% to 15% of the workforce. Although this supply is predicted to be sufficient to cover the losses caused by retirements, the report acknowledges that this supply will not be evenly distributed across all regions of the country.

International and U.S. Nurse Workforce Supply and Retention

A survey of national nursing associations by the International Council of Nurses revealed that 90% of these associations are somewhat or extremely concerned that heavy workloads, insufficient resourcing, and burnout and stress related to the pandemic response are the key drivers resulting in increased numbers of nurses who have left the profession and increased reported rates of intention to leave this year and when the pandemic is over (International Council of Nurses, 2021). Twenty percent of national nursing associations reported an increased rate of nurses leaving the profession in 2020, and studies from associations around the world have consistently highlighted increased intention-to-leave rates.

Due to existing nursing shortages, the aging of the nursing workforce, and the growing COVID-19 effect, the International Council of Nurses now estimates that 10.6 million nurses will need to be added to the global workforce by 2030 to fill the global nurse shortage gap.

Despite reports of professional burnout and stress on the workforce, a recent study demonstrated the resiliency of the U.S. workforce. In a study of 904 nurses from Japan, Republic of Korea, Republic of Turkey, and the United States, resiliency was associated with nurses receiving organizational support, nurses being involved in the development of policies, and nurses’ country of practice. Mean resilience was greater for U.S. nurses than those of other countries participating in the study (Jo, 2021). Another study examined the factors that increased resilience among healthcare providers during COVID-19. A survey conducted by Munn et al. (2021) (n = 2,459) indicated that greater resilience is associated with positive perceptions of leadership support, the organization’s understanding of the emotional support needed by staff, deployment policy, availability of educational resources, and psychological safety.

While the long-term effects of COVID-19 on the U.S. nursing workforce remain to be seen, many regions are beginning to attribute a decline in workforce supply to burnout from the sustained pandemic response, and nurse leaders are raising alarms about the forthcoming consequences. On September 1, 2021, the president of the American Nurses Association (ANA) sent a letter to the secretary of the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) expressing deep concern that “this severe shortage of nurses, especially in areas experiencing high numbers of COVID-19 cases, will have long-term repercussions for the profession, the entire health care delivery system, and ultimately, on the health of the nation” (ANA, 2021, p.1). The letter cited the following examples of shortages of nursing staff being reported across the country:

-

•

Mississippi has reported that it has seen a decrease of 2,000 nurses since the beginning of 2021.

-

•

Tennessee hospitals are operating with 1,000 fewer staff than at the beginning of the pandemic, prompting them to call on their National Guard for reinforcements.

-

•

Texas is recruiting 2,500 nurses from outside the state, a number that still will fall short of expected demand.

Vaccine Mandates and the Nursing Workforce

On August 23, 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) fully approved the Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccine for use in adults aged 16 or older (FDA, 2021). Subsequently, the Biden administration announced a rule, finalized in November 2021, requiring all healthcare workers at facilities that participate in Medicare and Medicaid to be vaccinated (Reed, 2021a). Even prior to the vaccine approval, many private employers made the decision to require COVID-19 vaccination as a condition of employment. At the time of FDA approval, the American Hospital Association estimated that 35% of hospitals already mandated the COVID-19 vaccine for their staff (Reed, 2021b), and that percentage continued to climb as the Federal mandate was drafted and finalized (Reed, 2021b; Hughes, 2021).

Some U.S. regulatory bodies took additional steps to ensure public protection. The District of Columbia Health Regulation and Licensing Administration made vaccination a requirement of licensure, requiring licensees in all licensed healthcare professions to attest by September 30, 2021, that they had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, or they would face disciplinary action, which could include license suspension, revocation, or non-renewal (DC Health, 2021). Similarly, in Oregon, Governor Kate Brown rescinded the option for healthcare workers to be regularly tested for COVID-19 in lieu of receiving the vaccine, requiring all healthcare workers to be fully vaccinated by October 18, 2021 (State of Oregon Newsroom, 2021). In response, the Oregon BON issued a temporary rule that failure to comply with Oregon Health Authority COVID-19 vaccine rules would be added to the list of actions considered conduct unbecoming a licensee in the state’s nurse practice act (NPA). Any nurse reported to be not in compliance would be subject to a due-process investigation and possible discipline. The Oregon BON addressed licensee concerns about the impact on the profession by stating that “the Board does not have jurisdictional authority to favor the profession over its role as a state agency and protection of the public” (Oregon Board of Nursing, 2021, p.2). The temporary rule will be made permanent if the Oregon Health Authority’s rules regarding vaccination are also made permanent.

In the face of vaccine mandates, concerns were raised about the potential losses to the healthcare workforce if practitioners chose to leave their positions rather than receive the vaccine. As of November 2021, these losses appear to represent a small percentage of the workforce. According to a compiled list of self-reports by health systems as individual vaccine mandates come into effect, the majority of health systems lost approximately 1% or less of their workforce through resignations or terminations related to the mandate (Muoio, 2021).

Officials acknowledge, however, that even a 1% reduction in workforce is problematic at a time when many health systems already find their workforces strained. As New Mexico Health Department Acting Head Dave Scrase pointed out, unvaccinated staff requiring extended leave due to infection and illness would also place a strain on the system (Kornfield & Timsit, 2021). In some instances, the losses have been sufficient to temporarily suspend or consolidate certain services normally offered by the health system, such as imaging or maternal health (Muoio, 2021; Kornfield & Timsit, 2021). It should be noted that a given health system’s mandate compliance rate is not representative of its vaccination rate, as the granting of religious or medical exemptions is not uniform and varies from system to system. In some cases in which larger percentages of employees left their positions, it may have been the case that the criteria for exemption were less lenient (Kornfield & Timsit, 2021).

Post-Pandemic Workforce Dynamics

While workforce dynamics prior to the pandemic were disrupted by globalization and emerging technologies, the disrupting factor for the future will be location of the worksite.

A McKinsey Global Institute report (Lund et al., 2021) makes three major predictions about the state of the post-COVID-19 workforce. First, remote work will likely continue after the pandemic. In advanced economies, this could be at a rate 4 to 5 times higher than pre-pandemic levels. Such an increase in remote work could have an impact on the greater geography of the workforce as fewer workers commuting may mean fewer services are required to take place in major metropolitan centers. Second, workplaces with high physical proximity—such as medical care—will continue to innovate ways to reduce physical exposure via automation and machine learning. Third, there will likely be a shift in demand, away from low-wage jobs and toward high-wage jobs, which will require low-wage workers to develop new skills. According to the report’s analysis of the workforce in eight countries, as many as 1 in 16 workers may have to transition to new occupations by the year 2030 to account for changing demand. These changes are expected to disparately impact women and minorities in many of the countries analyzed (Lund et al., 2021).

The report specifies that demand for healthcare workers will likely continue to remain high (Lund et al., 2021), which is in line with many workforce projections in the United States. Taken together with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s (2021) charge to increase health equity, an opportunity comes into focus for nurse educators, employers, and regulators to take steps now to facilitate the entry of these displaced workers into the nursing profession.

Implications for Regulators

It is important to note that even the most current workforce data, from any source, comprise just a snapshot of a moment that is already past; therefore, the fallout of a sustained public health emergency on the nursing workforce remains to be seen. Regulators should prepare for the possibility that the pandemic will lead to a wave of retirements. There is a future opportunity to use the data most healthcare regulatory bodies already collect on their licensees to project workforce needs at the state and regional level and to enact steps to mitigate shortages before they begin. This possibility was noted in NCSBN’s global research agenda (Alexander et al., 2021), which calls upon researchers to explore the practical applications of these existing resources.

Education

Nursing education in 2021 continued to be challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic, though the context was different from that in 2020. While many of the alternative strategies used in 2020 continued, there was a steady movement toward normality in 2021. Similarly, there was more comfort in using novel technologies and a recognition that many of the successful innovations could continue.

COVID-19 Impact on Nursing Education

In 2020, faculty and students had to quickly pivot to mostly online didactic education and adapt clinical experiences to compensate for loss of access to clinical sites, either through increased in-person simulation, virtual simulation, or other innovative strategies. By 2021, although COVID-19 and the more contagious Delta variant were still considerations, nursing programs began to normalize to what they were pre-pandemic. An informal survey of BONs in October 2021 found that the majority of nursing students in the 33 responding states had returned to clinical facilities, although percentages varied by region. Nearly half of respondents (45%) reported that the percentage of online didactic education was about the same as in pre-pandemic times; 39% reported that the percentage of online education was less than in 2020, though it was still significant; 16% reported that the percentage of online didactic education was about the same as seen during the pandemic in 2020 (NCSBN, unpublished findings).

The effects of the pandemic on nursing education are wide-ranging. In a systematic review conducted in Spain (Goni-Fuste et al., 2021), researchers evaluated 48 articles regarding the experiences of nursing students during global pandemics, from 2003 to 2020, and identified the following themes:

-

•

Education, including knowledge of the pandemic and the need for flexibility and finding creative ways for students to complete their education

-

•

Concern about risk and preventive behavior

-

•

Willingness to work during an outbreak

-

•

Emotional impact on the students

-

•

Ethical dilemmas.

These themes are similar to those found in U.S. studies during the COVID-19 pandemic (Emory et al., 2021; Feeg et al., 2021a; Michel et al., 2021).

Additionally, U.S. studies on the impact of COVID-19 on nursing education revealed concerns by students that that pandemic-based changes in nursing education delivery have left them unprepared for practice. In a qualitative survey of 993 students on the impact of the pandemic, Feeg et al. (2021a) uncovered worries about passing the NCLEX because of the changes incurred due to the pandemic. Likewise, in a national survey of 620 nursing students by Emory et al. (2021), 58% of the students reported their fear that the changes in learning experiences will affect their success on licensure examinations. Additionally, more than 53% of the students surveyed in Emory et al.’s (2021) study expressed concern that the quality of their care would be affected because of the alternative teaching strategies, which is a significant concern to regulation, education, and practice.

Nursing students in the United States also expressed concerns about lacking in-person clinical experiences and their difficult adjustment to online learning. These concerns were emerging themes in Michel et al.’s (2021) study of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on undergraduate students (n = 772 for the quantitative questions and n = 540 for the qualitative questions). For example, one student stated that book learning cannot replace hands-on experience. Another worried that the lack of clinical experiences would create barriers to finding a job. Similarly, in their qualitative findings, Emory et al. (2021) reported a theme that online schooling was not effective. Michel et al. (2021) suggested that schools of nursing, practice partners, and regulators should collaborate to facilitate clinical experiences during times of crisis. Interestingly, while U.S. students clearly preferred direct patient care over simulation (Michel et al., 2021), in other parts of the world there was a concern that simulation programs were not yet widely available for nursing schools (Sümen & Adibelli, 2021).

Given nursing students’ fears about alternative teaching strategies affecting their passage of the NCLEX, national pass rates (NCSBN, 2021b) for 2020 and 2021 (through July 30), along with the 2 years prior to that, are compared in Table 1 .

Table 1.

NCLEX Pass Rates Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Examination |

Pre-Pandemic |

During Pandemic |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

| NCLEX-RN | 88.29% N = 163,238 |

88.18% N = 171,387 |

86.57% N = 177,407 |

83.75% N = 104,298 |

| NCLEX-PN | 85.91% N = 47,031 |

85.63% N = 48,234 |

83.08% N = 45,661 |

80.01% N = 21,808 |

There was a slight decline in pass rates in 2020 and 2021 (through July 30). Although further study would be required to determine the causes of this slight decline, it is possible that the alternative education strategies used by nursing programs during the pandemic were contributory.

The Future of Nursing 2020–2030 asserted that the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the deficiencies in the nursing workforce’s preparedness to respond to public health and other disasters and identified nursing education as one avenue toward addressing this gap (National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, 2021). This deficiency exists not only in the nursing curriculum, but also in the infrastructure of programs themselves. Michel et al. (2021) noted the lack of emergency preparedness of nursing programs as evidenced by the haphazard movement to remote teaching and the abrupt removal of students from clinical facilities. They suggest that future planning should address how disasters may affect students, their clinical experiences, collaborative agreements, and regulatory requirements. Planning should address delivery of the courses while considering the comfort of both the students and the faculty. Additionally, students need to receive safety training about the disaster, including how to don and doff personal protective equipment. Emory et al. (2021) found that 30.8% of their student respondents reported not having any safety training related to caring for patients with COVID-19. This lack of readiness to care during a disaster was also found globally. For example, in a study of nursing student readiness to care for COVID-19 patients in Turkey, nearly three quarters of the students (n = 967) did not consider the curriculum to be sufficient in terms of readiness for a global crisis.

One important question is how the COVID-19 pandemic affected new graduate nurse employment in 2020. The National Student Nurses’ Association surveys their members annually about student nurse post-graduation employment, and their 2020 survey reports that overall employment of new graduates was 85% in 2020, down from 87% in 2019 and 89% in 2018 (Feeg et al., 2021b). See Figure 3, Figure 4 for employment trends across the country. Employment trends for new graduates in 2020 were down in all regions but the South. The lowest employment was in the West (77%) and Northeast (79%), which reflected the areas most affected by the pandemic during that time. The 2021 data were not available, but it will be interesting to see if this downward trend in new graduate employment continues.

New graduate nurses who found employment during the pandemic reported unique challenges in their transition into nursing practice. In a mixed methods descriptive study of 295 new graduates who began employment in July 2020, researchers at one academic medical center studied the impact of COVID-19 on new graduate preparedness for professional practice (Smith et al., 2021). The sample represented graduates from 136 nursing programs across 38 states. Interestingly, of the 295 participants, only 8 indicated they had completed their full clinical experience requirements. The new graduates reported that up to 240 clinical hours were replaced by either virtual simulation or another experience. Because of this, many new graduates lost in-person clinical hours with one or more clinical specialties, including those with medical-surgical, maternity, psychiatric, or community health patients. Many reported that there were large gaps in time (e.g., several months) since they had hands-on direct patient care. One student had not been in the clinical setting since the fall of 2019. The new graduates overall feared being overwhelmed or unsafe in their practice. Smith et al. (2021) recommend further research on the impact of COVID-19 on new graduates related to their competency, confidence, resiliency, and retention. Additionally, there is a need for more intense transitioning of these graduates, with leadership that supports new graduates in a residency program with trained preceptors.

While the COVID-19 pandemic certainly was challenging for nursing students, it is heartening to note that there has been an increased interest in nursing as a career. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) reported that in 2020, there was a 5.6% increase in enrollment in baccalaureate nursing programs (AACN, 2021a). A continuing concern, however, is the faculty shortage that is limiting the number of qualified students who can be admitted to nursing programs.

Faculty Vacancy Positions

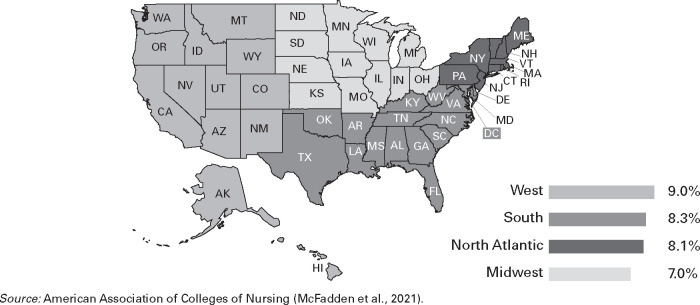

The AACN’s Special Survey on Vacant Faculty Positions for Academic Year 2021-2022 (McFadden et al., 2021) reports the issues and trends related to nursing faculty in baccalaureate or higher nursing education. According to their research, the total number of budgeted faculty positions has continued to increase since 2009, with a larger spike in 2021 than in previous years (Table 2 ). The 2021 survey data also shows a larger growth in the faculty vacancy rate (8%) compared to the 2020 data.

Table 2.

Nursing Program Full-time Faculty Positions and Needs, 2009-2021

| Faculty Positions and Needs | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of budgeted faculty positions | 18,511 | 19,830 | 21,533 | 21,685 | 22,649 | 22,838 | 24,539 |

| No. of faculty vacancies (vacancy rate) | 1,328 (7.1%) | 1,567 (7.9%) | 1,565 (7.3%) | 1,715 (7.9%) | 1,637 (7.2%) | 1,492 (6.5%) | 1,965 (8%) |

| No. of filled faculty positions (filled rate) | 17,183 (92.9%) | 18,263 (92.1%) | 19,968 (92.7%) | 19,970 (92.1%) | 21,012 (92.8%) | 21,346 (93.5%) | 22,574 (92%) |

| Mean faculty vacancies per school | 3.1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2 | 1.84 | 1.69 | 2.1 |

| Range of faculty vacancies | 1–26 | 1–36 | 1–31 | 1–38 | 1–26 | 1–31 | 1–31 |

| No. of schools with faculty vacancies | 429 | 461 | 480 | 488 | 475 | 461 | 576 |

| No. of schools with no faculty vacancies, need additional faculty | 130 | 133 | 128 | 138 | 134 | 136 | 118 |

| Number of schools with no faculty vacancies, do not need additional faculty | 182 | 220 | 224 | 245 | 284 | 287 | 241 |

There are more schools overall with faculty vacancies (n = 576) than in 2020 and the previous eleven years. Regional data reveals that the Midwest is experiencing the lowest vacancy (7%) compared to the South (8.1%), North Atlantic (8.3%) and West (9%) regions (Figure 6 ).

Figure 6.

Full-time Faculty Vacancy Rates by Region, 2021-2022 Academic Year

According to the AACN’s faculty vacancy survey (McFadden et al., 2021), the largest barriers to nursing education programs hiring new faculty members are in line with previous years’ data and are identical to the top four barriers identified in 2020:

-

•

Nursing programs have inadequate funds to hire additional faculty

-

•

The administration is unwilling to commit to more full-time positions

-

•

Competition for jobs in other marketplaces causes an inability to recruit qualified faculty

-

•

Qualified applicants for faculty positions are unavailable in the geographic area needed.

Furthermore, nursing programs continue to report the same critical issues related to faculty recruitment (McFadden et al., 2021):

-

•

Noncompetitive salaries

-

•

Finding faculty with the right specialty mix

-

•

A limited pool of doctorally prepared faculty

-

•

Finding faculty willing and able to teach clinical courses

-

•

Finding faculty willing and able to conduct research

-

•

High faculty workload.

Other notable critical issues concerning faculty recruitment that schools are reporting remain consistent with data from 2020 (McFadden et al., 2021):

-

•

Challenging location (rural areas or those areas with a high cost of living)

-

•

Institutional budget cuts or restrictions

-

•

Finding faculty who fit well with the school culture

-

•

Recruitment from historically underrepresented populations.

The overall number of schools experiencing faculty vacancies continues to increase across the United States. These data trends suggest these numbers will continue to rise.

Simulation in Prelicensure Nursing Programs

Educators have been left with many questions in the wake of clinical site closures during the pandemic. What ratio of clinical hours to simulation hours can be used to substitute for clinical experiences (Haerling [Adamson] & Prion, 2021)? What are the outcomes of traditional supervised clinical experiences (Leighton et al., 2021)? Can virtual simulation substitute for clinical simulation (Badowski et al., 2021)? These are all critical questions that need more research.

Hayden et al.’s (2014) landmark study on simulation, which provided evidence that simulation can be substituted for up to 50% of traditional clinical experiences with no significant difference in outcome, used a 1:1 ratio of clinical experience hours to simulation hours. While a couple of studies (Curl et al., 2016; Sullivan et al., 2019) have investigated using a 2:1 ratio, with promising results, these studies only included a small number of nursing programs and students. Additional and more robust studies are needed to guide future policy.

Other researchers studied virtual simulation, which they defined as screen-based simulation, for meeting students’ needs. In a retrospective, multisite, exploratory descriptive study with 97 prelicensure nursing students from three universities, investigators compared student perceptions of virtual simulation in meeting student learning needs to traditional clinical experiences and manikin-based simulation environments using the Clinical Learning Environment Comparison Survey (CLECS) 2.0 (Badowski et al., 2021). The researchers found that traditional clinical experiences met students’ perceived needs on all six subscale items, manikin-based simulation met the perceived needs in two areas, and virtual simulation met the perceived needs in four areas. These findings suggest that virtual simulation can be used to supplement traditional clinical experiences; however, more robust studies on virtual simulation are needed before it can replace traditional clinical experiences. In a systematic review of virtual simulation in nursing education studies from 1996 to 2018, Foronda et al. (2020) found virtual simulation to be a promising strategy, citing the high number of exploratory and other descriptive designs as well as the variability of objectives, conditions, equipment, and samples in the studies included. They recommended randomized controlled trials to elevate the science of virtual simulation.

Much of the current data on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, when clinical experiences are limited, suggest the importance of in-person clinical experiences. Yet, Leighton et al. (2021) uncovered evidence that the outcomes of traditional clinical experiences have not been rigorously studied. They attempted to conduct a systematic review on learning outcomes of traditional clinical experiences in nursing education but came up empty systematic—that is, no studies met their criteria. They suggest that we need sound scientific inquiry on the how to rigorously evaluate nursing education outcomes. Likewise, although one large mixed-methods study (Spector et al., 2020) suggested that clinical experiences with patients are critical to nursing education, it is unclear what specifically constitutes quality clinical experiences.

Practice-Academic Partnerships

A primary challenge for many nursing students throughout the pandemic was as visitors to clinical sites, they were barred from entering their clinical training sites during the pandemic (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021). However, one positive outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic is an increased interest in practice facilities and education programs collaborating to form practice-academic partnerships (Gilliss et al., 2021; Honig et al., 2021; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021; Robertson et al., 2021; Spector et al., 2021; Zerwic et al., 2021). Under this model, education programs partner formally with institutions to provide hands-on clinical experiences to nursing students while allowing them to simultaneously earn academic credit for their experiences. In a practice-academic partnership, students are classified as essential workers rather than as visitors to a clinical site, allowing access to clinical experiences during public health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nursing education programs used a variety of models for these partnerships. In some cases, students were able to work as paid nurse technicians in partnering medical centers (Honig et al., 2021); in others, students were unpaid, but the partnership enabled clinical experiences to continue (Zerwic et al., 2021). Some partnerships utilized unique care settings, such as community-based integrated primary care (Mixer et al., 2021) or, in one case, a partnership between a nursing education program, a health system, and a YMCA (Cooper, 2021). These valuable models provide essential primary and preventive care experiences to students while also giving them experience caring for diverse or underserved populations. Regardless of the model, the status of these partnerships was solidified when national nursing leaders released a policy brief in support of them on March 27, 2020 (NCSBN, 2020).

While guiding principles and best practices from these partnerships are beginning to appear in the literature (Zerwic et al., 2021; Gilliss et al., 2021), some notable recommendations for future practice-academic partnerships are the inclusion of nurse regulators in the partnership model (Spector et al., 2021) and the development of valid and reliable outcome measures to effectively evaluate partnerships once they are in place (Robertson et al., 2021).

Vaccine Resistance

As COVID-19 vaccines became widely available in early 2021, several BONs reported the emergence of a new challenge to the completion of clinical experiences. Although data suggest that the vast majority (86%) of students were vaccinated or planned to be as of August 2021 (National Student Nurses’ Association, 2021), as clinical facilities began to require all staff to be vaccinated, students who were not vaccinated were unable to complete the clinical requirements of their nursing programs at these facilities. Both educators and regulators expressed uncertainty about how to proceed; therefore, NCSBN convened a group of leaders from BONs and key nursing organizations to discuss the matter and develop a policy brief. The policy brief (NCSBN, 2021c) included the following recommendations:

Students should be vaccinated so that they can participate in clinical experiences.

-

•

Nursing programs should educate vaccine-hesitant students and address the myths and misleading information about the vaccines.

-

•

Course descriptions should state that clinical experiences are required.

-

•

Programs are mandated by accreditors and BONs to provide clinical experiences, but they are not obligated to provide students with alternative experiences if the students cannot participate in the experiences provided.

-

•

Other vaccines are often required by clinical facilities; the COVID-19 vaccine is not different.

-

•

BONs have no obligation to waive students’ clinical experience requirements.

-

•

Accommodations for medical or sincerely held religious beliefs should be decided on a case-by-case basis.

Trends and Analyses of Nursing Education Programs

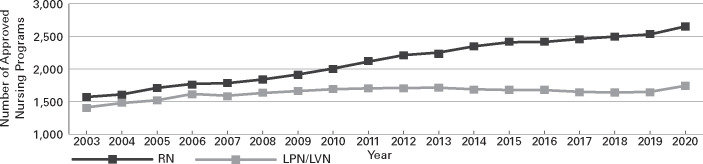

NCSBN has been analyzing trends of new U.S. RN and LPN/LVN education programs since 2003 and using these data as a proxy for predicting future workforce numbers. The percentage of growth since 2003 for RN programs is 69% and for LPN programs is 23%. RN program growth continues to steadily increase over the years. LPN/LVN program growth decreased from 2013-2018, but growth increased in 2019 and 2020 (NCSBN, 2021d) (Figure 7 ).

Table 3.

Number of Approved Nursing Programs in the United States, 2003–2020

| Year | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPN | 1,411 | 1,478 | 1,520 | 1,617 | 1,590 | 1,632 | 1,661 | 1,690 | 1,703 | 1,710 | 1,712 | 1,689 | 1,678 | 1,676 | 1,650 | 1,638 | 1,650 | 1,742 |

| RN | 1,571 | 1,610 | 1,710 | 1,771 | 1,783 | 1,839 | 1,915 | 2,007 | 2,112 | 2,212 | 2,252 | 2,347 | 2,410 | 2,414 | 2,460 | 2,496 | 2,530 | 2,652 |

Figure 7.

Number of Approved Nursing Programs in the United States, 2003–2020

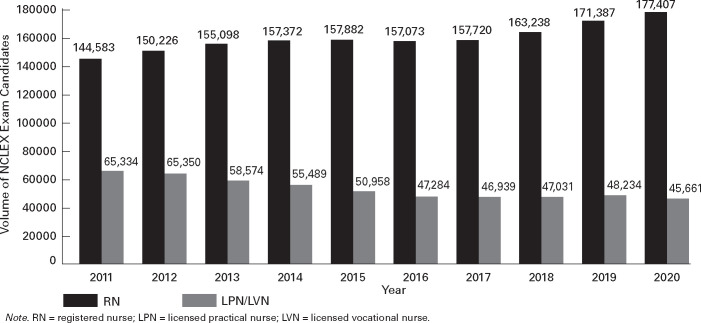

In addition to collecting annual approved nursing program data, NCSBN evaluates trends for the numbers of first-time NCLEX test takers to predict the future nursing workforce. Upon examining the 10-year trend of first-time NCLEX takers in the United States (2011-2020), the number of RN first-time NCLEX takers plateaued between 2014–2017; however, since 2018, there has been a growing increase (NCSBN, 2021b). There was a gradual decline in first-time NCLEX-PN takers from 2012-2016, with a small rise occurring from 2017 to 2019, but in 2020, the number of NCLEX-PN test takers decreased to its lowest number in 10 years (Figure 8 ).

Figure 8.

Ten-Year Trend of U.S. RN and LPN/LVN First-time NCLEX Takers, 2011-2020

A 10-year analysis of U.S. RN first-time NCLEX takers by program type exhibited that although associate degree nursing (ADN) graduates accounted for the largest number of nursing program graduates for the majority of the 10-year period, the number of baccalaureate degree nursing graduates has grown considerably. In 2020, the number of baccalaureate-degree nursing graduates surpassed the number of associate degree graduates (NCSBN, 2021b). Furthermore, the growth of baccalaureate degree graduates over the 10 years is 52%, while that of ADN graduates over the same 10-year period is 4.5% (Table 4 ). This increase is in line with the past Future of Nursing report (Institute of Medicine, 2011) recommendation to increase the percentage of BSN-educated nurses in the workforce.

Table 4.

Ten-Year Trend of U.S. RN First-time NCLEX Takers by Program Type, 2011–2020

| Year | Baccalaureate Degree | Associate Degree | Diploma |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 58,146 | 82,764 | 3,476 |

| 2012 | 62,535 | 84,517 | 3,173 |

| 2013 | 65,406 | 86,772 | 2,840 |

| 2014 | 68,175 | 86,377 | 2,787 |

| 2015 | 70,857 | 84,379 | 2,607 |

| 2016 | 72,637 | 81,653 | 2,745 |

| 2017 | 75,944 | 79,511 | 2,222 |

| 2018 | 79,235 | 82,000 | 1,968 |

| 2019 | 84,298 | 84,794 | 2,247 |

| 2020 | 88,643 | 86,520 | 2,180 |

Note. RN = registered nurse.

Graduate Nursing Education Trends in the United States

The recent AACN Annual Surveys (Fang et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2021) revealed an increase in enrollments in master’s, doctoral (research-focused), and doctor of nursing practice (DNP) programs (4.1%, 0.9%, and 8.9%, respectively) despite pandemic-related concerns. The number of graduates also increased during the same period in master’s (2.9%) and DNP (14.6%) programs, but there was a decrease (-5.7%) in graduates in research-focused doctoral programs (Table 5 ).

Table 5.

Enrollment and Program Graduates Across Master’s, Doctoral (Research-Focused), and Doctor of Nursing Practice Programs, 2019 and 2020

| 2019 | 2020 | % Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment | |||

| Master’s | 146,059 | 152,054 | 4.1% |

| Doctoral (research-focused) | 4,584 | 4,625 | 0.9% |

| Doctor of nursing practice | 36,096 | 39,301 | 8.9% |

| Program Graduates | |||

| Master’s | 49,844 | 51,280 | 2.9% |

| Doctoral (research-focused) | 803 | 757 | -5.7% |

| Doctor of nursing practice | 7,949 | 9,110 | 14.6% |

Note. Data are from the same schools reporting in 2019 and 2020.

In conjunction with the increase in enrollments and graduations, a small increase was seen from 2019 to 2020 in the percentage of enrollees who are part of an ethnic minority across all three levels of programs (35.3% in 2019 to 37.1% in 2020 for master’s enrollees; 33.3% in 2019 to 33.8% in 2020 for research-focused doctoral enrollees, and 36.0% in 2019 to 37.1% in 2020 for DNP enrollees), as well as a slight increase in the percentage of graduates in DNP programs who are part of an ethnic minority.

There was a decrease in the percentage (from 31.9% in 2019 to 28.0% in 2020) of research-focused doctorally prepared graduates who are part of an ethnic minority (Fang et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2021). There was no change in the percentage of graduates in master’s level programs in this category.

Slight decreases were also found for the same time period when comparing the percentage of male enrollees in master’s (12.0% in 2019 to 11.7% in 2020) and research-focused doctoral programs (11.1% in 2019 to 10.5% in 2020) and male graduates in master’s and DNP programs. However, an increase was seen in the percentage of male enrollees in DNP programs as well as male graduates in research-focused doctoral programs (Fang et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2021).

The AACN Annual Survey (Fang et al., 2021) compared enrollment and graduation data by area of study in master’s level programs in schools reporting in both 2019 and 2020. The percentages of NP students and graduates have increased (4.5% and 5.3%, respectively) while the percentages of students and graduates in clinical nurse specialist (-8.1% and -13.5%, respectively) and nurse anesthesia (-28.1% and -7.9%, respectively) programs have decreased. Nurse-midwifery programs experienced increased enrollments (2.8%) but a decrease in graduates (-7.1%). Community/public health and forensic nursing experienced noteworthy increases from 2019 to 2020 in student enrollment while case management and clinical nurse leader programs showed evident decreases in the percentage of graduates in the same period (Table 6 ).

Table 6.

Enrollment and Graduation in Master’s Level Programs in the Same Schools Reporting in 2019 and 2020

| Program | 2019 | 2020 | Change in Number | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Nurse Specialist | ||||

| Students | 792 | 728 | -64 | -8.1% |

| Graduates | 288 | 249 | -39 | -13.5% |

| Nurse-Midwifery | ||||

| Students | 1,578 | 1,622 | 44 | 2.8% |

| Graduates | 521 | 484 | -37 | -7.1% |

| Nurse Anesthesia | ||||

| Students | 1,825 | 1,313 | -512 | -28.1% |

| Graduates | 813 | 749 | -64 | -7.9% |

| Clinical Nurse Leader | ||||

| Students | 2,330 | 2,114 | -216 | -9.3% |

| Graduates | 1,167 | 881 | -286 | -24.5% |

| Nurse Practitioner | ||||

| Students | 90,329 | 94,367 | 4,038 | 4.5% |

| Graduates | 28,018 | 29,499 | 1,481 | 5.3% |

| Combined Nurse Practitioner/Clinical Nurse Specialist | ||||

| Students | 52 | 55 | 3 | 5.8% |

| Graduates | 20 | 25 | 5 | 25.0% |

There are multiple entry points for becoming an NP. Enrollment and graduation data for master’s and post-master’s NP programs as well as post-baccalaureate and post-master’s DNP programs were reported in the AACN Annual Surveys (Fang et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2021). A comparison of the data reported in 2019 and 2020 shows a notable increase in both family NP and psychiatric and mental health NP enrollment and graduation in the master’s NP and post-baccalaureate DNP programs. The same increase can be seen when comparing enrollment and completion data in post-master’s psychiatric and mental health NP programs; however, a decrease is seen in family NP enrollment and graduation in this category (Table 7 ).

Table 7.

Enrollment and Graduation in Master’s NP, Post-Master’s NP, Post-Baccalaureate DNP, and Post-Master’s DNP Programs, 2019 and 2020

| Master’s NP |

Post-Master’s NP |

Post-Baccalaureate DNP |

Post-Master’s DNP |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus Area | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Total Enrollment | 90,401 | 94,751 | 8,248 | 8,525 | 15,625 | 16,947 | 4,192 | 4,169 |

| Total Graduation | 28,071 | 29,587 | 3,168 | 3,593 | 2,805 | 3,139 | 1,047 | 1,269 |

| Family NP | ||||||||

| Schools | 354 | 364 | 269 | 280 | 205 | 217 | 72 | 70 |

| Students | 58,761 | 59,774 | 3,185 | 2,584 | 8,756 | 9,354 | 1,008 | 714 |

| Graduates | 19,194 | 19,696 | 1,260 | 1,196 | 1,533 | 1,793 | 126 | 120 |

| Pediatric Primary Care NP | ||||||||

| Schools | 70 | 71 | 57 | 58 | 57 | 58 | 21 | 24 |

| Students | 2,472 | 2,456 | 155 | 105 | 732 | 796 | 112 | 92 |

| Graduates | 920 | 946 | 56 | 82 | 146 | 132 | 7 | 10 |

| Women’s Health NP | ||||||||

| Schools | 33 | 32 | 25 | 27 | 23 | 23 | 9 | 9 |

| Students | 1,429 | 1,477 | 101 | 62 | 279 | 282 | 16 | 12 |

| Graduates | 421 | 494 | 40 | 41 | 43 | 50 | 2 | 4 |

| Neonatal NP | ||||||||

| Schools | 28 | 28 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 11 | 9 |

| Students | 789 | 832 | 46 | 73 | 262 | 311 | 29 | 29 |

| Graduates | 280 | 269 | 16 | 15 | 56 | 58 | 5 | 5 |

| Pediatric Acute Care NP | ||||||||

| Schools | 28 | 26 | 31 | 34 | 25 | 23 | 9 | 9 |

| Students | 631 | 671 | 87 | 128 | 326 | 363 | 28 | 29 |

| Graduates | 183 | 195 | 86 | 46 | 42 | 57 | 5 | 9 |

| Psychiatric & Mental Health NP | ||||||||

| # of Schools | 128 | 139 | 142 | 164 | 101 | 114 | 41 | 43 |

| Students | 10,635 | 13,673 | 3,105 | 3,937 | 1,836 | 2,209 | 504 | 608 |

| Graduates | 1,923 | 2,682 | 993 | 1,468 | 317 | 370 | 78 | 120 |

| Adult Gerontology – Primary Care NP | ||||||||

| Schools | 140 | 140 | 108 | 106 | 97 | 103 | 27 | 26 |

| Students | 6,525 | 6,312 | 528 | 542 | 1,506 | 1,342 | 121 | 102 |

| Graduates | 2,524 | 2,387 | 252 | 228 | 301 | 296 | 25 | 14 |

| Adult Gerontology – Acute Care NP | ||||||||

| Schools | 104 | 109 | 106 | 114 | 73 | 83 | 21 | 25 |

| Students | 8,261 | 8,526 | 989 | 1,032 | 1,573 | 1,813 | 148 | 167 |

| Graduates | 2,370 | 2,661 | 440 | 495 | 289 | 310 | 11 | 20 |

| NP Dual Population Foci | ||||||||

| Schools | 32 | 30 | 17 | 13 | 22 | 38 | 14 | 9 |

| Students | 898 | 921 | 28 | 27 | 355 | 477 | 21 | 60 |

| Graduates | 256 | 198 | 10 | 10 | 78 | 73 | 1 | 18 |

Note: NP = nurse practitioner. All data presented as n.

The percentage of enrollments and graduates from master’s programs continues to exceed those of DNP programs. The adult gerontology enrollment and graduation rates were increased in the acute care NP population, but the primary care student enrollment and graduation rates decreased. In the pediatric populations both the pediatric primary care NP and pediatric acute care NP enrollment and graduations increased generally with a slight reduction in post-baccalaureate DNP graduation in the pediatric primary care group. Post-master’s NP pediatric acute care NP enrollment increased while graduation decreased.

The AACN annual surveys from 2020 and 2021 demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic has not negatively impacted enrollment in master’s level, research-focused doctoral, and DNP programs. The following trends were identified when comparing the 2021 survey with the prior year:

-

•

Increased percentage of NP program enrollment and graduation with a subsequent decrease in percentage of CNS and nurse anesthesia program enrollment and graduation and decrease in nurse-midwifery graduation

-

•

Greater percentage of master’s level enrollment and graduation as compared to DNP programs

-

•

Increased percentage of enrollment and graduation in psychiatric and mental health NP master’s, post-master’s, post-baccalaureate DNP, and post-master’s DNP programs

-

•

Increased percentage of adult gerontology acute care NPs as compared to adult gerontology primary care NP enrollment and graduation

-

•

Increased percentage of enrollment in community/public health and forensic nursing programs.

Nurse Practitioner Program

In December 2019, The National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (NONPF) and the AACN convened a national task force to review and revise the current Criteria for the Evaluation of Nurse Practitioner Programs (5th ed.) (NONPF, 2016).

These evaluation criteria, combined with accreditation standards, are the foundation for evaluation of NP programs and used by the programs themselves, as well as program accreditors, to evaluate the quality of NP educational programs (AACN, 2016; Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing, 2017).

These standards are reviewed and revised through a consensus-based process every 3 to 5 years to ensure NP program quality. Nineteen organizations are participating in the development of The Standards for Quality Nurse Practitioner Education, 6th Edition, which culminates in the January 2022 release of the Criteria for the Evaluation of Nurse Practitioner Education Programs, 6th edition (NONPF, in press). The criteria are organized into 4 chapters: (a) standards focus on institutional support, (b) resources to support program quality, (c) curriculum, and (d) systematic evaluation processes to promote ongoing quality improvement. Criteria elaborate on the components of the standard and provide the necessary requirements to meet each standard.

The criteria are degree neutral and do not differentiate between master’s or doctoral programs; they apply to all NP educational programs.

The task force accepted over 500 comments from multiple listening sessions and an interactive webinar following the release of the draft document. Most of the comments involved the increase of direct clinical hours from 500 to 1,000 hours with the option of 250 hours of simulation.

PhD Nursing Education Programs in the United States

Nurse researchers are crucial for generating evidence-based policies in areas such as nursing education. However, the overall percentage of nursing faculty with PhD degrees is decreasing. The total number of nursing faculty across the United States increased by 21% between 2013 and 2018; however, that growth was disproportionately among those holding DNPs. While faculty holding PhDs grew by 12%, faculty with DNPs grew by 158% (Fang & Zhan, 2021). Although DNP holders are filling the faculty gap to some extent, a growing number of nursing faculty hold PhDs in non-nursing disciplines (Algase et al., 2021). Algase et al. (2021) suggest that the knowledge these faculty bring from other disciplines may advance nursing science in several ways; however, the authors also raise important questions about these faculty, such as the driving force behind this trend.

With the dearth of PhD-holding faculty, focus has turned to increasing the pipeline of new PhDs. The completion rate of PhD students during the 2013–2018 period was 74.2%, taking an average of 5.7 years to graduate. Those most likely to leave the program before graduating tended to be male students, part-time students, students in post-baccalaureate programs, students who were not faculty or were part-time faculty, or students with more than 24% of their courses being taught online (Fang & Zhan, 2021). In 2019, the University of Pennsylvania convened a summit to discuss the state of PhD education (Broome et al., 2021). Several innovations, such as a focus on team science, were presented. The participants recognized that they must try different approaches to mentoring, including team and peer mentoring. The mentor must be able to connect the students with a larger network of researchers and scholars. Similarly, Morris et al. (2021) noted that facilitating growth in the way students think (e.g., exposing them to diverse opinions and thought processes) is important preparation for stewardship of the discipline in which PhD nurses will lead. Puzantian & Darwish (2021), from Lebanon, also addressed innovations in PhD nursing programs. They asserted that traditional measurement courses focus on the psychometric evaluation of instruments measuring cognition and behavior; however, in the age of big data, precision medicine, and translational science, PhD students should be taught across the measurement spectrum.

Measuring Outcomes: National Nursing Education Core Database

Based on indications from a large mixed-methods study on nursing program quality indicators, which also resulted in regulatory guidelines for nursing education programs (Spector et al., 2020), NCSBN developed a nursing education core database, launched in fall 2020, intended to assist BONs in measuring outcomes for their nursing education programs. While most BONs already required an annual report of each of their nursing education programs, the database assists with this process, providing a common annual report template with a core set of evidence-based questions to all participating BONs. BONs may also customize the report template with their own additional questions and opt into 16 questions related to COVID-19.

The data are used by each participating BON (22 BONs were participating as of October 2021) to monitor their programs for warning signs that are highlighted in the report. The tool allows BONs to identify any areas of weakness so that programs can make changes before their approval statuses are affected and their NCLEX pass rates drop, keeping in mind that NCLEX pass rates are lagging indicators of nursing program performance. This allows nurse regulators and nursing education programs to be proactive in making improvements. Annually, NCSBN will analyze and report the aggregate data, revising and refining the associated regulatory guidelines (Spector et al., 2020), as necessary. Nursing regulatory bodies outside the United States have also expressed interest in participating in the project.

The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education

On April 6, 2021, AACN’s membership approved The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education (the Essentials) (AACN, 2021b). This document departs from previous editions given the changes in higher education and the rapidly evolving healthcare system. The AACN asserts that new thinking and new approaches are necessary to educate nurses for the future. The new Essentials document also incorporates contemporary trends in nursing education, which include:

-

•

Diversity, equity, and inclusion

-

•

Four spheres of care, namely: disease prevention/promotion of health and well-being; chronic disease care; regenerative or restorative care; and hospice/palliative/supportive care

-

•

Systems-based practice

-

•

Informatics and technology

-

•

Academic-practice partnerships

-

•

Career-long learning.

A major change in the Essentials document is the recommended integration of competency-based education into the curricula, thereby holding students accountable for mastering the competencies at their level of education. The document also outlines competency domains, competencies, and sub-competencies with a levelled approach (AACN, 2021b), which would allow a seamless transition from entry level nursing to advanced nursing fields, such as APRNs. AACN has developed several resources, including webinars, for faculty to use when incorporating competency-based education into their curriculum (AACN, 2021b).

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) has become a renewed topic of interest after a series of events in 2020 sparked a national conversation about racial inequity (Morrison et al., 2021). Recent research points to the benefits of prioritizing DEI and highlights the barriers to true inclusion that still exist in nursing. In a literature review on DEI, using Melnyk’s levels of evidence, Morrison et al. (2021) found that increased diversity in the healthcare workforce led to improved quality of care, better financial performance, more innovation, increased team communication, decreased health disparities, and positive outcomes; these improvements were achieved by developing policies and practices that generated a climate of inclusion. An ethnographic study of Black nurses in the United States (Iheduru-Anderson, 2021) sought to better understand how racism or racial bias affects attitudes and/or actions toward career development in academia and nursing leadership. Identified themes included discrimination and stereotyping, nursing while black (pressure to conform), fear (of job loss, being silenced, etc.), nursing leadership dynamics (paying lip service to diversity), and resilience and disillusionment (“Why bother?”). The researcher concluded that because nursing education provides the foundation for practice, it is critical to address racism in the curriculum. Similarly, in a phenomenological design, other researchers studied the experiences of 11 Black/African American nursing students (Hill & Albert, 2021). They identified the themes of resolve to succeed, ineffective education models, a need for support of the college experience, and finding Black/African American mentors. Some of the barriers cited were inadequate college preparation, a feeling of isolation, and an inability to connect with other students.

To create a more diverse nursing workforce, many schools of nursing are using holistic admissions that consider individual experiences and attributes as well as traditional metrics such as grades and test scores. Lewis et al. (2021) studied outcome measures of three cohorts of their accelerated bachelor of science in nursing (ABSN) program before they used holistic admissions (n = 274) and then three cohorts of ABSNs after implementing holistic admissions (n = 283). They found that while the diversity of their students increased, on-time graduation and licensure pass rates remained stable. These findings suggest that holistic admissions in nursing education can increase diversity, while at the same not adversely affecting outcomes. More research on the outcomes of holistic admissions is important for the future.

Bennett et al. (2021) studied the progression of students in their nursing program from 2012 to 2016 (n = 2,498), tracking them from pre-nursing to taking the NCLEX. They found that 57% were lost prior to the nursing program application, and of those, losses were higher in the minority group (Bennett et al., 2021). A major barrier for Black/African American students was not succeeding in the science courses. However, once the minority students moved past the pre-nursing science barriers, they were likely to be successful in the program. In fact, 100% of the African American students passed the NCLEX on their first attempt. This study suggests that remedial programs should be implemented in the pre-nursing period rather than once the students have already entered the nursing program, when interventions are often given.

The Future of Nursing 2020–2030 identified the further diversification of the nursing workforce as a key step in addressing health inequity and social determinants of health (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021). The report committee calls for education programs to create environments of inclusion and consistent support for the economic, social, and professional needs of their students. The research described in the preceding paragraphs provides insight into the steps that may be taken to realize this recommendation.

Promoting Equity

With health equity as its central focus, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report (2021) also highlighted the importance of equity’s promotion within the nursing curriculum in addition to the makeup of the program cohort. The report challenges nurse educators to go beyond mere inclusion of content on the social determinants of health and to integrate these discussions across the entire nursing curriculum, including through experiential learning opportunities in diverse communities. The report notes that BSN programs are more likely to contain health equity concepts than other prelicensure nursing programs (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021), which further demonstrates the value of the previous Future of Nursing report’s call for an increase in BSN-educated nurses (Institute of Medicine, 2011). Additionally, the 2021 report notes that additional research into social determinants of health is essential to advancing the knowledge base of nursing practice through evidence-based findings. For this reason, it is vital that the supply of PhD-prepared nurses in the workforce remains steady (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021).

Consistency in Global Standards and Strategies

With the growing prominence of cross-border practice in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, consistency in practice and education standards, both within countries and across countries, is paramount.

In April 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) published strategic directions for nursing and midwifery through the year 2025 (WHO, 2021a), which also provides direction for nursing education programs globally. These evidence-based practices and policies can help countries ensure that nurses are optimally educated for meeting their patients’ needs and other population health goals. The WHO cites a growing global call for the minimum education of a nurse or midwife to be at the baccalaureate level. Policy priorities for nursing education include:

-

•

Align the levels of education with optimized roles within the health and academic systems. With this priority, they recommend considering “bridge” programs for upgrading the credentials of students.

-

•

Optimize domestic production of midwives and nurses to meet or surpass health system demand from both the public and private sector. They acknowledge that in many countries this will mean investments to facilitate faculty development and to address infrastructure and technology constraints.

-

•

Design education programs to be competency-based, apply effective learning design, meet quality standards, and align with population health needs. As discussed previously, in the United States, AACN has also made this recommendation in “Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education.”

-

•

Ensure faculty are properly trained in the best education methodologies and technologies with demonstrated expertise in content areas. This will require advanced training of faculty, as well as investments in digital technologies and clinical simulation.

With a similar eye toward the harmonization of nursing education standards, the Global Alliance for Nursing Education and Sciences (Baker et al., 2021) used a multinational methodology, reflecting consensus of leaders in nursing education, to develop the Global Pillars Framework to strengthen nursing education worldwide. These interrelated pillars are:

-

•

Pillar I: Competency expectations for new graduates. Learning outcomes are classified under knowledge and practice skills; communication and collaboration; critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment; and professionalism and leadership.

-

•

Pillar II: Guidelines for nursing education programs. Recommendations are organized under curriculum, admissions, and learning experiences.

-

•

Pillar III: Guidelines for education institutions. Strategies are classified under faculty, instructors, and preceptors; resources; leadership and administration; and outcomes.

This framework assumes nursing students will be educated at the baccalaureate level. Baker et al. (2021) assert that globally, we must start now to create a harmonized and modernized approach to nursing education.

Current and Future Nursing Students

Educators must be prepared for entry of students not properly prepared for the rigors of a nursing education program. For over a decade, reports have outlined the decline in K-12 education standards. This decline is alarming as it can impact learning in the higher levels of education (Loveless, 2021). Educators should be aware of these issues and nursing programs should be prepared to offer remediation and tutoring for students when necessary.

Implications for Regulators