Abstract

Hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is the gold-standard for measurement of portal hypertension, a common cause for life-threatening conditions such as variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy. HVPG also plays a crucial role in risk stratification, treatment selection and assessment of treatment response. Thus recognition of common pitfalls and unusual hepatic venous conditions is crucial. This article aims to provide a radiographical and clinical guide to HVPG with representative clinical cases.

Introduction

Portal hypertension is a common consequence in cirrhosis and can cause variceal bleeding, ascites and hepatic encephalopathy. It is defined as elevation of hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) >5 mmHg, but its complications mostly occur when HVPG is above 12 mmHg.1,2 Causes of portal hypertension can be categorized into pre-hepatic, hepatic and post-hepatic (Table 1).3

Table 1.

Causes of portal hypertension and their effects on HVPG

| Types of portal hypertension | Common causes | Changes in FHVP, WHVP and HVPG |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-hepatic | Portal/splenic vein thrombosis; Pancreatic cancer etc. | FHVP, WHVP, HVPG are normal |

| Hepatic | Pre-sinusoidal: Sarcoidosis | FHVP, WHVP, HVPG are normal |

| Sinusoidal: Cirrhosis by Viral/alcohol/NASH | FHVP normal, WHVP↑and HVPG↑ | |

| Post-sinusoidal: Budd Chiari | FHVP↑,WHVP↑and HVPG↑ | |

| Post-hepatic | IVC obstruction; Right heart failure | FHVP↑and WHVP↑, HVPG↑ or normal |

FHVP, free hepatic venous pressure; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; IVC, inferior vena cana; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; WHVP, wedged hepatic venous pressure.

Accurate measurement of HVPG is crucial for risk stratification and follow up of portal hypertension. HVPG is calculated by subtracting the free hepatic venous pressure (FHVP) from the wedged hepatic venous pressure (WHVP) (HVPG = WHVP-FHVP). The median of three readings is taken as HVPG.

FHVP is measured when the pressure-sensitive catheter is positioned at the distal portion of hepatic vein without occluding flow, while WHVP is measured when the balloon catheter is inflated to occlude flow, thus providing a standing column to the portal vein via the hepatic sinusoid.4 In this regard, it is analogous to pulmonary wedged capillary pressure measurements.

Measurement of HVPG

Equipment

The following equipment are used in our HVPG measurement procedure.

Imaging: Ultrasound; digital subtraction angiography

Medications: 1% Lidocaine; iodinated contrast

Basic consumables: Gauzes; puncture needles; syringe

Catheters and wires: 4Fr Multipurpose A catheter (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN); 5.5Fr ‘over-the-wire’ Fogarty balloon catheter (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA); 6Fr Sheath (Terumo, Hatagaya, Japan); 0.035” Amplatz guide wire (1 cm tip, Boston scientific, Marlborough, MA); 0.035” Stiff hydrophilic guidewire (Terumo, Hatagaya, Japan); pressure monitoring kit (Biosensor, Singapore).

Detailed steps

After local anesthesia infiltration, the internal jugular vein is accessed under ultrasound guidance using 18G needle.

A 6F sheath is inserted over a guide wire. Usually the right hepatic vein (RHV) is cannulated with a 4F MPA catheter and a 0.035” stiff hydrophilic guidewire.

On the lateral view, the RHV can be differentiated from the middle hepatic vein (MHV). RHV traverses posteriorly/en face while the MHV will point more anteriorly. (Figure 1a and b).

Digital subtraction venography is then performed to exclude strictures and hepatic venous collaterals.

The catheter is then manipulated to a deeper portion of the vein, a 0.035” Amplatz wire (1 cm straight tip) is inserted and the 4F MPA catheter is then exchanged for the 5.5F occlusion balloon catheter.

With the balloon inflated, another digital subtraction venography is performed to ensure adequate occlusion. If significant hepatic-venous to hepatic-venous (HV-HV) shunts or vessel stricture are identified, an alternative vein should be cannulated.

FHVP is measured with balloon deflated 1–2 cm from the inferior vena cana (IVC) (or as near to the IVC as reasonably possible) and after stabilization of readings (typically after 45–60 s, Figure 1c). The transducer should be at the level of the heart with appropriate zeroing. Waveform of FHVP measurement is shown in Figure 1f.

WHVP is measured with the balloon inflated and after stabilization of readings (typically after 45–60 s, Figure 1d). Another way of measuring WHVP is by wedging a 4F catheter against the wall of the vein without use of balloon occlusion catheter (Figure 1e), however, this is not practiced at the Singapore General Hospital as we feel that this will lead to variability due to local tissue and procedurist factors. Waveform of WHVP is shown in Figure 1g.

Three sets of readings are obtained.

The following pressures are then recorded:

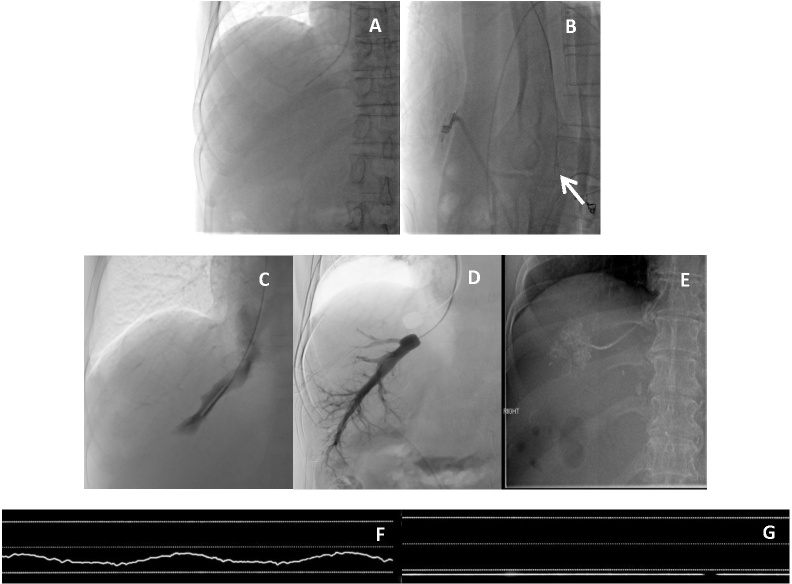

Figure 1.

Routine measurement of HVPG. Anterior view (a) and lateral view (b) showing the catheter coursing posteriorly in lateral view (arrow) indicating cannulation of the right hepatic vein. Measurement of FHVP and WHVP. (c): Balloon deflated to measure FHVP; d): Balloon inflated to measure WHVP, digital subtraction venogram confirmed good vessel occlusion and absence of HV–HV shunts. (e): Example of WHVP measurement by wedging catheter against a small hepatic vein branch in a different patient. (f) Sample waveform of FHVP measurement; g) Sample waveform of WHVP measurement. FHVP; free hepatic venous pressure; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; WHVP, wedged hepatic venous pressure.

IVC at the level of renal and hepatic veins (a sudden rise in pressure gradient may suggest IVC stenosis, albeit rare.)

Right atrium

Pulmonary artery (if RA pressure more than 8 mmHg)

To ensure accuracy, the following criteria need to be fulfilled: (1) measurements were replicated for at least three times to ensure reproducibility; (2) there should not be any negative pressure reading if possible; (3) measurements should be consistent and variation should not be more than 2 mmHg.4 If the difference between measurements is more than 2 mmHg, additional measurements will be performed. The first three measurements within 2 mmHg difference will be used for HVPG calculation.

Interesting cases discussion

Case 1: Routine HVPG measurement

Background: 61 year-old Chinese male with decompensated cirrhosis with unknown etiology electively admitted for HVPG measurement and liver biopsy.

Readings: FHVP: 11/12/12; WHVP: 29/29/29; HVPG 17 (mmHg)

This is in keeping with severe portal hypertension. Biopsy showed the cause to be primary biliary cirrhosis.

Case 2: Follow-up HVPG measurement

Background: 53 year-old Chinese female with background non-alcoholic steatohepatitis cirrhosis, presented with variceal bleeding requiring ICU admission. The first HVPG measurement was done during her inpatient stay. Patient was then treated with propranolol 60 mg PO 3 times per day for 4 weeks. A follow-up HVPG measurement was performed at the similar location to assess treatment response (Figure 2).

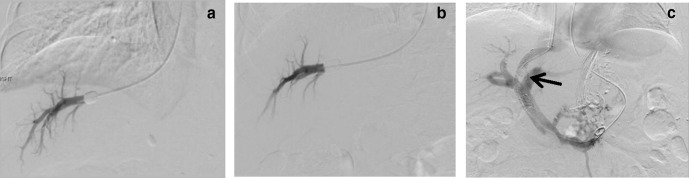

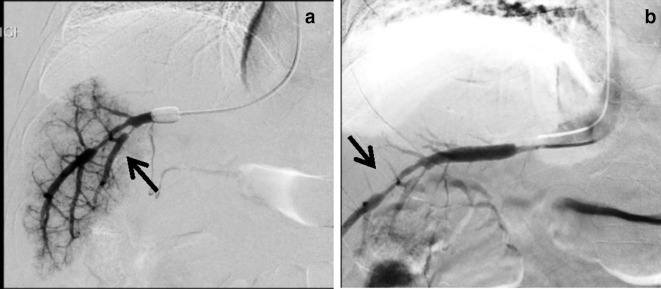

Figure 2.

Serial HVPG. Initial (a) and follow up (b), HVPG measurements at similar locations. (c): Patient was eventually treated with TIPS (arrow). HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Pre-β blocker readings: FHVP: 15/15/16; WHVP: 39/39/38 (mmHg); HVPG: 24 mmHg.

Post-β blocker readings: FHVP: 14/15/15; WHVP: 36/36/37 (mmHg); HVPG: 21 mmHg.

One of the clinical applications of HVPG measurement is to assess treatment response. For reproducible and accurate measurements, a similar location was chosen to perform the second HVPG measurement. Repeat HVPG was only mildly reduced in this patient. Significant improvement is generally taken as reduction of HVPG to below 12 mmHg or a 20% reduction from the baseline HVPG.5 In view of failed medical treatment, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure was performed to better control her symptoms.

Case 3: Presence of multiple HV–HV shunts

Background: 60 year-old Malay male with liver cirrhosis secondary to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and Hepatitis B.

Readings: FHVP: 14/16/16; WHVP 18/19/19 (mmHg); HVPG: 3 mmHg

HVPG measurement was only 3 mmHg, which was abnormally low. Venogram showed extensive HV–HV shunts (Figure 3a, arrow), which could account for his abnormally low HVPG readings.

Figure 3.

Presence of HV–HV shunts and HVPG measurement at alternative site a) Presence of extensive HV–HV shunts (arrow) on venography, which may result in falsely low HVPG; b) Measurement of FHVP in left hepatic vein; c) Wedged venogram of left hepatic vein showed no HV–HV shunting. HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; WHVP, wedged hepatic venous pressure.

Routinely, right hepatic vein is used as the preferred site for HVPG measurement due to its accessibility and fitness for standardization. However, if there were multiple HV–HV shunts present on the right, the left hepatic vein could be used as an alternative, which in this case showed no significant HV–HV shunts (Figure 3b and c) and yielded HVPG of 14 mmHg.

Case 4: Arterioportal (AP) shunting causing portal hypertension.

Background: 60 year-old Chinese male, presented with hematemesis secondary to esophageal varices.

Readings: FHVP:16/18/18; WHVP: 28/28/28 (mmHg); HVPG: 10 mmHg

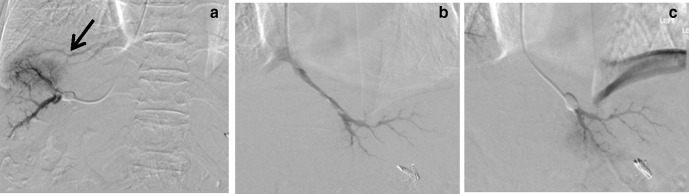

While the HVPG is not severely elevated, CT scan revealed an AP shunt, a rare cause of portal hypertension. This is evident by early opacification of the portal vein during arterial phase (Figure 4c) and catheter angiogram (Figure 4d). Treatment for this condition would be embolization of AP shunt, using coils in this instance (Figure 4e). Post-embolization, the patient reported improvement in symptoms.

Figure 4.

Presence of AP shunts and portal hypertension. Measurement of FHVP (a) and WHVP (b), no obvious venogram abnormality. (c): However, CT abdomen showed opacification of portal vein during CT arterial phase (arrow), indicating presence of AP shunt. Embolization of AP shunt. (d) Pre-embolization, solid arrow indicates the presence of AP shunt, dash arrow indicates the hepatic artery. (e) Post-embolization of AP shunt with 3 mm coils, dashed arrow indicating the hepatic artery. AP, arterioportal; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; WHVP, wedged hepatic venous pressure.

Case 5: Budd Chiari syndrome as post-hepatic cause of portal hypertension

Background: 62 year-old Indian male, admitted for refractory ascites from presumed alcohol-induced liver cirrhosis. His venogram shows multiple stenoses in the hepatic veins, consistent with early Budd Chiari syndrome (Figure 5A and B)5 This patient was eventually treated with a TIPS procedure.

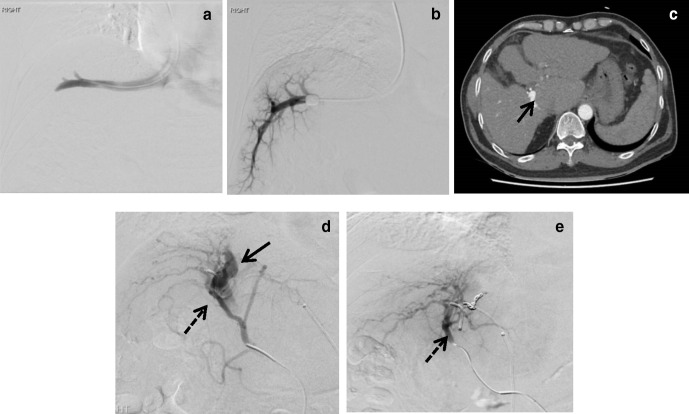

Figure 5.

Budd Chiari syndrome and portal hypertension. (a, b): WHVP and FHVP measurements showing multifocal hepatic vein stenoses (arrows) .

Case 6: Pulmonary hypertension causing portal hypertension (Post-hepatic cause).

Background: 49 year-old Malay male presented with recurrent ascites and was diagnosed to have early cirrhosis. However, he was a non-drinker and his hepatitis serology tests were negative. Notably, he had one previous episode of non-ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).

Readings: FHVP: 16/16/16; WHVP: 20/20/19 (mmHg); Right atrial pressure: 16 mmHg (normal <6 mmHg); Pulmonary arterial pressure: 35 mmHg (normal <25 mmHg); HVPG: 4 mmHg.

Even though the patient’s HVPG was normal, in our protocol, pulmonary arterial pressure is measured if the right atrial pressure is above 8 mmHg (Figure 6). This is a classic example of a cardiopulmonary (post hepatic) cause of portal hypertension with a normal HVPG.

Figure 6.

Pulmonary arterial pressure measurement. Tip of pigtail catheter in the main pulmonary artery.

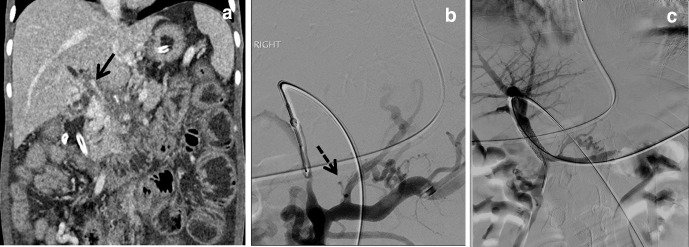

Case 7: HVPG in portal vein stenosis (pre-hepatic cause)

Background: 34 year-old Chinese female with history of disseminated TB presented with intestinal obstruction and ascites.

Readings: FHVP: 5/6/6 (mmHg); WHVP: 8/9/9 (mmHg); HVPG: 3 mmHg.

While HVPG readings were normal, CT scan showed significant main portal vein stenosis secondary to compression from surrounding lymphadenopathy (Figure 7a). This patient was treated by main portal vein stenting (Figure 7b and c).

Figure 7.

Portal vein stenosis with normal HVPG. a: CT scan (coronal view) showing patient with diffused lymphadenopathy causing obstruction of main portal vein (arrow). b: Direct venogram showed significant stenosis. Multiple collaterals (dash arrow) were present. c: A stent was inserted via a left portal vein puncture, leading to restoration of blood flow. HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient

Conclusion

When performed in a standardized fashion, HVPG can diagnose portal hypertension, gauge response to treatment and guide further management. Procedurists should look out for HV–HV shunts which may underestimate portal hypertension. Pre- and post-hepatic causes can yield normal HVPG, thus measuring right atrial and pulmonary arterial pressures, in addition to careful review of imaging should be performed if needed.

Contributor Information

Qiqi Lu, Email: qiqi.lu@mohh.com.sg.

Sum Leong, Email: leong.sum@singhealth.com.sg.

Kristen Alexa Lee, Email: kristen.alexa.lee@singhealth.com.sg.

Ankur Patel, Email: ankur.patel@singhealth.com.sg.

Jasmine Ming Er Chua, Email: jasmine.chua.m.e@singhealth.com.sg.

Nanda Venkatanarasimha, Email: nanda.kumar@singhealth.com.sg.

Richard HG Lo, Email: richard.lo.h.g@singhealth.com.sg.

Farah Gillan Irani, Email: farah.gillan.irani@singhealth.com.sg.

Kun Da Zhuang, Email: zhuang.kun.da@singhealth.com.sg.

Apoorva Gogna, Email: apoorva.gogna@singhealth.com.sg.

Pik Eu Jason Chang, Email: jason.chang@singhealth.com.sg.

Hiang Keat Tan, Email: tan.hiang.keat@singhealth.com.sg.

Chow Wei Too, Email: toochowwei@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Groszmann RJ, Bosch J, Grace ND, Conn HO, Garcia-Tsao G, Navasa M, et al. Hemodynamic events in a prospective randomized trial of propranolol versus placebo in the prevention of a first variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 1990; 99: 1401–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91168-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Tsao G, Groszmann RJ, Fisher RL, Conn HO, Atterbury CE, Glickman M. Portal pressure, presence of gastroesophageal varices and variceal bleeding. Hepatology 1985; 5: 419–24. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840050313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parikh S. Hepatic venous pressure gradient: worth another look? Dig Dis Sci 2009; 54: 1178–83. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0491-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tey TT, Gogna A, Irani FG, Too CW, Lo HGR, Tan BS, et al. Application of a standardised protocol for hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement improves quality of readings and facilitates reduction of variceal bleeding in cirrhotics. Singapore Med J 2016; 57: 132–7. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2016054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suk KT. Hepatic venous pressure gradient: clinical use in chronic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2014; 20: 6–14. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2014.20.1.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]