Abstract

The efficacy of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men (MSM) is contingent upon consistent adherence. Digital pill systems (DPS) provide real-time, objective measurement of ingestions and can inform behavioral adherence interventions. Qualitative feedback was solicited from MSM who use stimulants to optimize a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-based intervention (LifeSteps), used in conjunction with a DPS, to promote PrEP adherence (PrEPSteps). Seven focus groups and one individual qualitative interview were conducted in Boston, MA with cisgender, HIV-negative MSM who reported stimulant use and current PrEP use or interest. Focus groups and interviews explored reactions to the DPS and PrEPSteps messaging components: contingent reinforcement (CR), corrective feedback (CF), LifeSteps, and substance use Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT). Quantitative assessments were administered. Qualitative data were analyzed using applied thematic analysis. Twenty MSM participated. Most were White (N = 12), identified as homosexual or gay (N = 15), and college-educated (N = 15). Ages ranged from 24 to 68 years (median 35.5). Participants were willing to engage with the DPS and viewed it as beneficial for promoting adherence. Confirmatory CR messages were deemed acceptable, and a neutral tone was preferred. CF messages were viewed as most helpful and as promoting individual responsibility. LifeSteps was perceived as useful for contextualizing nonadherence. However, SBIRT was a barrier to DPS use; concerns around potential substance use stigma were reported. MSM who use stimulants were accepting of the DPS and PrEPSteps intervention. CR, CF, and LifeSteps messages were viewed as helpful, with modifications pertaining to tone and content; SBIRT messages were not preferred.

Keywords: Digital pills, HIV prevention, Ingestible sensors, Medication adherence, Technology acceptance model

Implications.

Practice: Behavioral interventions that respond to real-time adherence data through a digital pill can be optimized to address nonadherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Policy: Deployment of digital pill systems to measure HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis should consider the addition of interventions that use digital pill data as an overarching architecture.

Research: Future research should be aimed at measuring the effectiveness of digital pill-based interventions to maximize HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence.

INTRODUCTION

Once-daily oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP; tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine) is a highly efficacious biomedical tool in preventing new HIV infections; however, its effectiveness is closely linked to medication adherence, to help end the HIV epidemic [1]. Men who have sex with men (MSM) are more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to experience concomitant psychosocial challenges like depression, anxiety, and substance use [2] which can contribute to increased risk for HIV transmission [3] or acquisition [4]. These challenges can lead to disruptions in daily routines and to instances of PrEP nonadherence [5, 6]. Neurocognitive changes associated with substance use may also contribute to difficulties designing a structured routine to support medication adherence behavior [7, 8]. Finally, the existence of comorbid mental health and substance use disorders can cause shame surrounding missed medication doses, which can further exacerbate PrEP nonadherence [9]. Among MSM who use PrEP, those with substance use disorders have greater difficulty achieving continuous adherence and may be at increased risk of HIV acquisition [10–12]. One study of 104 MSM on PrEP found that use of club drugs (e.g., methamphetamine, cocaine) increased the odds of missing a PrEP dose by 55% the same day and 60% the following day [13].

Many empirically supported behavioral interventions exist to help support PrEP adherence among MSM. These strategies range from sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) tailored to specific barriers to adherence among MSM to text-based interventions that provide push reminders, to use PrEP to peer navigators that promote both PrEP uptake and continuance [14–16]. These interventions can effectively improve PrEP use, but they promote adherence during clinical visits, or in response to inferred nonadherence events and therefore miss opportunities to intervene in the context of daily suboptimal adherence [6, 17]. Among existing digital health interventions that deliver adherence-boosting interventions to individuals proximal to nonadherence events, these tools are often limited by an inability to objectively confirm medication ingestion events [18].

There are many direct and indirect techniques to measure PrEP adherence. Direct measures include ingestible sensors, video-based observed therapy, and pharmacologic assays utilized to measure drug concentrations. Indirect measures include self-reported adherence, pill counts, pharmacy records, and electronic adherence monitors (EAMs) [19–21]. However, these tools lack the capacity to directly measure and confirm medication ingestion events in real-time. The use of a digital pill system (DPS) that measures PrEP ingestion patterns offers a novel opportunity to understand suboptimal adherence and simultaneously deliver behavioral content, in real-time, that accounts for proximal ingestion patterns. DPS comprise a hard gelatin capsule with an integrated electronic radiofrequency emitter, which overencapsulates a drug (e.g., PrEP). When ingested, the gastric chloride ion gradient activates the radiofrequency emitter, transmitting ingestion time data to a wearable Reader device [22]. The Reader stores ingestion data and relays it to a cloud-based interface, where clinicians can view real-time adherence information. Users have access to a paired smartphone application, where they can view historical ingestion data (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

The digital pill system (DPS; ID-Cap System, eTectRx, Gainesville FL) consists of an ingestible radiofrequency emitter that co-encapsulates PrEP (1); on ingestion, the digital pill is activated, and its signal is acquired by a wearable Reader (2), which relays ingestion data to a smartphone app which enables on-demand access to adherence data (3). The app simultaneously transmits ingestion data to a clinician dashboard (4) which allows for real-time monitoring of ingestion data.

Image courtesy of etectRx.

DPS have been previously found to be feasible methods for measuring adherence to antiretroviral agents, antituberculosis medication, antihyperglycemics, and opioids [22–28]; these investigations have also demonstrated that DPS are acceptable to patients. We have also previously demonstrated a willingness among MSM who use substances to interact with and operate a DPS to record PrEP ingestions; in this work, MSM described a preference to receive personalized messages that respond to adherence patterns, and reminders to help reinforce their PrEP adherence [29]. Two investigations have utilized DPS to measure adherence to ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for hepatitis C treatment, and to antihypertensives [30, 31]. These studies demonstrated that virological response in hepatitis C treatment was associated with adherence detected by the DPS, and that blood pressure control was achieved in the context of improved adherence to digitized antihypertensive medications. Most studies that have deployed the DPS to date have focused on the use of the technology to measure ingestion patterns and overall adherence. However, the ability to detect nonadherence in real-time also presents an opportunity to develop closed-loop systems that respond to discrete changes in adherence. In this context, DPS could then be used to respond to nonadherence at the moment it occurs, boost suboptimal adherence, and help support positive adherence behaviors [32].

One method to evaluate the integration of a novel intervention with the DPS is through the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM; [33]), a theoretical framework that has previously been utilized to understand the potential acceptance of technology-mediated PrEP adherence measurements [29, 34, 35]. Designing evaluations around TAM allows for the exploration of perceived use, intended use, and actual use of technology. Applied to a behavioral intervention that integrates with a DPS, TAM can guide explorations of how individuals may perceive the usefulness and methods of interaction with the system as a whole. Rather than developing an intervention by presenting it in isolation from its linked technology, TAM permits exploration of the interaction of an intervention within the technology, allowing for an evaluation of how individuals receive intervention components while they use the DPS.

The present study sought to develop and refine a novel CBT-based intervention (PrEPSteps) using real-time feedback from a DPS to enhance PrEP medication adherence in MSM with non-alcohol substance use. We presented the design of the PrEPSteps intervention in focus group discussions, informed by the TAM, to understand perceived use and intended use of the intervention among MSM with self-reported stimulant use. By integrating prospective user feedback into the intervention development process, we sought to refine and optimize the PrEPSteps intervention to support PrEP adherence in MSM with non-alcohol substance use.

METHODS

Participants

Recruitment strategies included outreach to patients in care at a Boston community health centers specializing in sexual and gender minority health and HIV care, advertising via social media platforms, community outreach via recruitment events in the greater Boston area, and flyers posted at local community health centers. Inclusion criteria included being: (a) 18 years or older, (b) cisgender MSM, (c) self-reported HIV-negative, (d) any self-reported stimulant use (e.g., methamphetamine/crystal meth, cocaine) over the past 6 months, and (e) self-report of current PrEP use or interest in taking PrEP. Individuals were excluded from participation if they did not speak English. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Fenway Health. Focus group discussions were conducted between September 2018 and June 2019.

Original PrEPSteps intervention

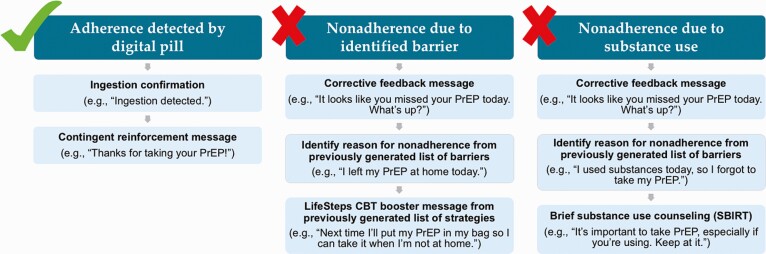

We developed PrEPSteps, a CBT-based intervention delivered via text message, housed within the architecture of the DPS, that is respondent to PrEP ingestion patterns. There are four major components to PrEPSteps: (a) contingent reinforcement (CR), (b) corrective feedback (CF), (c) LifeSteps, an empirically supported CBT-based intervention that has been shown to improve highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and PrEP adherence [36, 37], and (d) Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) centered around substance use (Fig. 2). To begin using the intervention, users first defined a customized dosing window (i.e., the daily time they anticipate taking PrEP). Next, users had an initial session of LifeSteps to learn about PrEP adherence. During this session, users identified several of their personal barriers to adherence and, through a discussion with a trained study team member, identify solutions to these barriers. As part of this discussion, users crafted customized messages for each potential solution, using their own words, which became the LifeSteps booster messages that were delivered to them via text following nonadherence events. Finally, users participated in a discussion of the intersection of substance use and PrEP adherence to highlight this as a potential reason for nonadherence. Each component of the PrEPSteps intervention was then delivered to users in response to prespecified PrEP ingestion patterns as detected by the DPS.

Fig 2.

| Schematic of the PrEPSteps intervention demonstrating respondent interventions delivered based on daily PrEP adherence and nonadherence.

CR messages

Each time a user successfully used the DPS for a PrEP ingestion (i.e., they ingested a digital pill and correctly operate the Reader), a CR text message is delivered to their smartphone to confirm that the ingestion has been detected, and to positively reinforce their adherence behavior.

CF messages

In the context of a nonadherence event (i.e., when no ingestion is detected by the DPS), users instead received a CF text message, which prompted them to identify and report the reason for their missed ingestion. Users then selected the most applicable reason for their missed dose from a personalized list of adherence barriers (which they previously specified during their initial LifeSteps session). Users’ responses to CF messages then linked directly to LifeSteps booster messages (described below). LifeSteps booster presents the user with their previously identified, personalized barriers to adherence.

LifeSteps booster messages

Once a user responded to a CF message identifying the barrier most applicable to their nonadherence event, they automatically received a LifeSteps booster message, which presented them with the personalized solution to the applicable barrier, which they themselves developed during the initial LifeSteps session.

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) messages

Finally, in the event that a user identified substance use as the reason for a given nonadherence event, they are presented with an SBIRT message, which aims to remind participants of the importance of PrEP adherence in the context of substance use and to provide them with a referral to substance use treatment if indicated.

Procedures

Screening and enrollment

Interested individuals were screened in-person at Fenway Health or via phone by a trained study member to confirm eligibility. Eligible individuals were then scheduled to join an in-person focus group discussion at Fenway Health. Prior to the start of each focus group discussion, participants were verbally consented as a group and then asked to individually complete a quantitative assessment (see measures below).

Focus group discussions

To obtain multiple opinions and understand how PrEPSteps may be used in the real world, we convened focus groups where participants could interact and provide feedback around each component of the intervention [38, 39]. We specifically wanted to facilitate interaction between participants to generate consensus around the appropriate tone and content of PrEPSteps intervention messages. Focus group discussions were audio-recorded and led by the PI and a trained study team member. Seven focus groups and one individual interview were conducted in total. The focus groups and interview followed a semi-structured format; discussions explored responses to digital pill technology and solicited feedback on the four components of the PrEPSteps intervention. After each focus group and interview, the facilitators debriefed and compiled a summary for distribution to the full study team, to ensure that all topics were adequately covered and to solicit feedback on the discussion; debriefs were also used to assess for thematic saturation between focus groups.

Refinement of the PrEPSteps intervention

Focus group discussions were utilized as a way to discuss the DPS with participants and develop its application for measuring and boosting PrEP adherence through the combination of DPS technology and brief CBT-based intervention. Iterative refinements to the structure and design of each component of the PrEPSteps intervention were made following each focus group, based on participant feedback.

Measures

Quantitative assessment

Participants completed a brief quantitative questionnaire before the focus group discussion, in which they self-reported demographic data, health information, sexual history, and substance use history. Demographic data included age, gender, race, ethnicity, income, education, sexual preferences, relationship status, and primary care provider information. Health history information included history of medical conditions, mental health problems, and sexually transmitted infections. Sexual history questions asked participants to report the number and type of partners with whom they had sexual encounters over the past three months, as well as their preferred sexual activities, condom use behavior, and use of substances before or during sexual activity. Finally, substance use questions included the frequency and type of substance use, and physical, behavioral, social consequences related to their substance use.

Semi-structured focus group discussions

A semi-structured focus group guide, informed by TAM, was used for each discussion. Focus groups centered around the perceived use of each component of PrEPSteps, as well as how participants would intend to use PrEPSteps when linked to the DPS. We also explored preferences around each intervention component, as well as for the content, tone, frequency, and mode of delivery of PrEPSteps. The focus group guide was piloted with two members of the study team (P.R.C., G.G.), who were trained by an expert in qualitative analysis specifically pertaining to technology development (R.K.R.). Focus groups lasted approximately 60 min and were conducted by P.R.C. We adhered to the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines in the design, analysis, and reporting of this investigation. Sample questions and probes are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

| PrEPSteps intervention components and sample focus group questions and probes

| Intervention component | Sample questions/probes |

|---|---|

| Contingent reinforcement (CR) | • How do you think it would feel to receive messages that congratulate you on taking your PrEP? |

| • What are some kinds of messages you would like to see to encourage you to take PrEP? | |

| Corrective feedback (CF) | • What happens if you forget to take your PrEP and the system sends you feedback on that? |

| • How would it feel to know you missed your PrEP dose and we (the research team) knew? | |

| LifeSteps boosters | • How would you feel if you received a LifeSteps booster on your phone if you did not take your PrEP? |

| • Do you think people would want to think about nonadherence in the moment it happens? | |

| Substance use-related Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) | • We understand that substance use may impact someone’s ability to take PrEP. How do you think we could best talk about substance use and PrEP in PrEPSteps? |

| • Would you be willing to interact with questions about your substance use in the setting of your digital pill PrEP ingestions? |

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for selected quantitative variables. Audio-recorded focus group discussions were professionally transcribed and reviewed for completeness, accuracy, and final de-identification. Two of the core components of the TAM (perceived use and intended use of technology) guided qualitative data interpretation. Data were analyzed using applied thematic analysis, whereby three study team members (G.G., Y.M., M.B.) developed both (a) deductive codes, using the TAM-based focus group guide as a template; and (b) inductive codes, to reflect emergent data and other novel concepts raised by participants [40]. Team members met regularly to develop the coding framework and to resolve discrepancies in data interpretation; an audit trail of codebooks was maintained for reference and comparison. Finally, all transcripts were double-coded by two team members (P.R.C., Y.M.); coding was facilitated by NVivo version 12 (QSR International). The coders reviewed the aggregate coding to identify key themes, and findings were presented to the full team for discussion and final interpretation.

RESULTS

A total of 91 individuals were screened, 53 were eligible, and 20 participated in a focus group discussion. Reasons for ineligibility included a lack of self-reported stimulant use in the past 6 months (n = 36), and a self-reported positive or unknown HIV status (n = 4); two participants were ineligible for both reasons. Among the 33 eligible individuals who elected not to participate in a focus group, reasons included scheduling conflicts (n = 8), moving out of town (n = 1), inability to contact (n = 1), not interested in participating (n = 7), and unknown (n = 16), Seven focus groups were conducted in total; the average length was 50.3 min. The eighth planned focus group was attended by only one participant, due to scheduling conflicts and drop-out among the other scheduled participants. We elected to conduct this session as an individual interview facilitated by study staff and included feedback from this participant in this analysis. Of the 20 enrolled participants, the median age was 35.5 years old (range 24–68) (Table 2). Most participants identified as White (60.0%), not Hispanic or Latino (80.0%), and homosexual or gay (75.0%); the majority had at least a college degree (75.0%).

Table 2.

| Sociodemographic characteristics

| Variable | Sample (N = 20) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Age (in years) | ||

| Median (range) | 35.5 (24–68) | – |

| Race | ||

| White | 12 | 60.0 |

| Black/African American | 2 | 10.0 |

| More than one race | 5 | 25.0 |

| Other | 1 | 5.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 | 20.0 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 16 | 80.0 |

| Education | ||

| High school graduate/GED | 3 | 15.0 |

| Some college education | 2 | 10.0 |

| College graduate | 5 | 25.0 |

| Some graduate education | 2 | 10.0 |

| Graduate/professional | 8 | 40.0 |

| Income (annual) | ||

| Less than $6,000 | 1 | 5.0 |

| $6,000 to $11,999 | 1 | 5.0 |

| $12,000 to $17,999 | 3 | 15.0 |

| $18,000 to $23,999 | 1 | 5.0 |

| $24,000 to $29,999 | 3 | 15.0 |

| $30,000 to $59,999 | 6 | 30.0 |

| More than $60,000 | 5 | 25.0 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Homosexual or gay | 15 | 75.0 |

| Bisexual | 3 | 15.0 |

| Other | 2 | 10.0 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 13 | 65.0 |

| In a committed relationship | 3 | 15.0 |

| In a domestic partnership | 3 | 15.0 |

| Married | 1 | 5.0 |

Quantitative results

Table 3 displays descriptive statistics for selected quantitative variables. Overall, participants reported a high rate of HIV risk behavior, reporting a median of five sexual partners during the past three months (IQR 2.5–30), with nearly half (44.4%) never using condoms in the past 30 days. Most participants (57.9%) had previously had an STD. The majority were currently taking PrEP (60.0%) at the time of the focus group, with just under half (41.7%) of these reporting at least one missed dose over the past 2 weeks. Almost all participants (89.5%) reported nonmedical stimulant use, as well as use of other substances, including alcohol (57.9%), marijuana (63.2%), hallucinogens (26.3%), and other substances like poppers (63.2%).

Table 3.

| Descriptive statistics for select quantitative measures

| Variable | Sample (N = 20) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Sexual partners in past 3 months | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (2.5–30) | – |

| On PrEP | ||

| Yes | 12 | 60.0 |

| No | 8 | 40.0 |

| Missed doses of PrEP in past 2 weeksa | ||

| Yes | 5 | 41.7 |

| No | 7 | 58.3 |

| Number of missed doses of PrEP in past 2 weeks | ||

| 0–2 doses | 3 | 60.0 |

| 3–4 doses | 1 | 20.0 |

| >4 doses | 1 | 20.0 |

| Condom use in past 30 daysb | ||

| Never | 8 | 44.4 |

| Almost never | 2 | 11.1 |

| Sometimes | 3 | 16.7 |

| Almost every time | 2 | 11.1 |

| Every time | 3 | 16.7 |

| Ever had an STDa | ||

| Yes | 11 | 57.9 |

| No | 8 | 42.1 |

| Diagnosed mental health problemsa | ||

| Anxiety | 6 | 31.6 |

| Depression | 5 | 26.3 |

| Bipolar disorder | 3 | 15.8 |

| Other | 4 | 21.1 |

| None | 9 | 47.4 |

| Nonmedical use of stimulantsa | ||

| Yes | 17 | 89.5 |

| No | 2 | 10.5 |

| Frequency of stimulant use in past 30 daysa | ||

| Never | 1 | 5.3 |

| One or two times | 11 | 57.9 |

| About once a week | 2 | 10.5 |

| Several times a week | 4 | 21.1 |

| About every day | 1 | 5.3 |

| Other substances in usea | ||

| Alcohol | 11 | 57.9 |

| Marijuana | 12 | 63.2 |

| Sedatives/tranquilizers | 2 | 10.5 |

| Opiates | 3 | 15.8 |

| Hallucinogens | 5 | 26.3 |

| Heroin | 2 | 10.5 |

| None | 1 | 5.3 |

| Other (e.g., poppers, amyl/butyl nitrate) | 12 | 63.2 |

aData missing from one participant.

bData missing from two participants.

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Qualitative results

Qualitative analyses revealed both barriers to and facilitators of the four core components of the PrEPSteps intervention. Within each component, participants identified elements that were acceptable, as well as those requiring modifications to improve usability and acceptability. The core components of PrEPSteps and participant responses to each are outlined below and in Table 4.

Table 4.

| Content areas and selected participant quotes

| Contingent reinforcement (CR) | |

| Perception of CR messages as motivating and confirming adherence behavior | “It would just feel rewarding… knowing that I’m preventing myself from being HIV positive.” (Age 35, not on PrEP) |

| “I mean, that way you know it worked, and you don’t have to think about it. With that in mind, I would want [the message] immediately because that way I know that what I did works, and it was processed.” (Age 25, on PrEP) | |

| Preference for confirmatory CR messages with a neutral tone, rather than positive feedback | “I personally would be annoyed by contingent reinforcement, in general, because it’s something I’m supposed to do, right, so when it becomes such mundane process that I’m not being congratulated for it, [it] sort of takes away the meanings of the congratulations that I get in other facets of my life.” (Age 25, on PrEP) |

| “I wouldn’t want ‘Thanks for taking your PrEP today’ or ‘Thank you for taking PrEP today. Keep it up.’ I feel like it’s something I should do. I shouldn’t be thanked for it.” (Age 63, not on PrEP) | |

| Acceptability of weekly CR messages to provide a snapshot of adherence | “To me, that feels like, if you’re gonna get a message every day, that that’s more course correctable… If I get it at the end of the week, I’m like, ‘I missed four days,’ You know what I mean? I’m like, ‘Oh, great.’ (Age 33, not on PrEP) |

| “My optimal thing is once a week… The everyday thing for me becomes part of whole big wall of info that I get, and it doesn’t reach me.” (Age 55, not on PrEP) | |

| Corrective feedback (CF) | |

| Perception of CF messages as aiding understanding of the context of one’s nonadherence | “It’s a good way of… [getting] me focused on figuring out I did forget. What can I do for myself to figure out how to keep on track of taking this pill?” (Age 36, on PrEP) |

| “At the beginning, some people will be like, ‘No, I don’t need a phone call. I can do it.’ Then they might realize that they haven’t been taking it. It’s up to them to sit there and be like, ‘Oh, I need to change that.’” (Age 35, not on PrEP) | |

| Acceptability of CF messages following nonadherence, and expectation of provider monitoring via DPS | “I feel like as a clinician, you should go in and check. If it’s because I’m on vacation and I forgot to take it, not because I’m too coked out of my mind to remember to take a pill, [it’s] just as simple as asking.” (Age 63, not on PrEP) |

| “If we’re trying to correct behavior [for] people who forget medication, then maybe this will help add some responsibility, like ‘you missed your PrEP, which is that specific medication that we talked about.’ That’s why this app’s here.” (Age 25, on PrEP) | |

| Desire for CF messages either daily or after two consecutive missed ingestions | “That’d be important, especially if someone didn’t realize that they missed it the first day, and then they [say], ‘Oh, I’m missing it today because I am out. I forgot. It’s not a big deal,’ but in reality, you missed two, maybe even three days at this point. If you are gonna be keeping track of it, you should let us know every single day.” (Age 24, on PrEP) |

| “Well, if I forgot one day, I think I would remember eventually that I didn’t take it. I mean hopefully I am committed to taking it, I’m gonna take it the next day. If it is two days, then there’s probably some kind of problem.” (Age 63, not on PrEP) | |

| Preference for concise, straightforward CF messages with a negative tone | “Everyone operates differently, but I personally would want a message that imbues some kind of fear… ‘By you not taking it regularly or you just missed a dose, you’re putting yourself at risk.’” (Age 25, on PrEP) |

| “I think just being short, to the point… ‘It looks like you missed your PrEP today. What’s up?’ Actually, that’s rather casual, I’d just say, ‘What’s happened?’” (Age 25, on PrEP) | |

| LifeSteps boosters | |

| Acceptability of interacting with self-generated LifeSteps booster messages after nonadherence events | “It’s another way of reminding [you] what are you doin’, step back, what are you doin’? This would be a good thing like, ‘well, why am I forgetting or what’s goin’ on?’” (Age 36, on PrEP) |

| “You would be more accountable because it is not someone else telling you. It is yourself. Like your conscience. LifeSteps is probably helpful ‘cause it’s your own words and language.” (Age 31, on PrEP) | |

| Perception that nonadherent individuals would not engage with LifeSteps booster messages, and belief that messages do not address the root causes of nonadherence | “If it was something like, ‘Oh, I was feeling down, so I didn’t take my PrEP.’ It’s like, ‘Do you need behavioral health services?’ Something that actually is gonna produce more change, as opposed to… I feel down and I’ve already identified that as a barrier, and now this is just a reminder notification… I just don’t think that goes anywhere. It seems a little bit shallow in terms of doing some of these behavioral changes or bringing the barriers down.” (Age 35, not on PrEP) |

| “I question the likelihood of the individual providing corrective feedback if they haven’t taken the pill. Feedback, in general, is something that’s hard to solicit. If you have chosen not to take the pill for whatever reason, I find it that you’re less likely to take it a step further and not provide feedback as to why.” (Age 25, on PrEP) | |

| Preference for ability to report adherence barriers not identified during initial LifeSteps session | “If there’s another option [where] you can write in, like why you forgot to take your PrEP that day, or why didn’t you take your PrEP that day.” (Age 31, on PrEP) |

| Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) | |

| Intrusiveness of a stand-alone SBIRT module that delivered queries around substance use | “I already feel bad about putting my own morals and everything at risk… I think to be reminded that you forgot to take your PrEP because you’re getting high, for me personally, would make me feel worse about myself.” (Age 35, not on PrEP) |

| “If I’m doing substances or I’m getting high or whatever, that’s a whole big section of life, right? If this thing is just to make sure that I’m adhering to PrEP, let’s just keep it at that. I don’t want to hear moralizing.” (Age 33, not on PrEP) | |

| Perception of SBIRT messages as acceptable and beneficial only with a nonjudgmental and nonconfrontational tone | “People have signed up for that and they know that there is that correlation between the PrEP and the stimulant use, so naturally that should be a question and that’s what you guys are trying to see.” (Age 54, not on PrEP) |

| “[These messages] are great because I think they address the reality of whatever perhaps guilt or shame or difficulty you’re going through as a result of your substance abuse issues and encourage you to take PrEP in spite of it and does not discount the difficulty that you’re actually going through. I think these [messages] should be framed… from a place of sensitivity and encouragement.” (Age 25, on PrEP) | |

| Preference for follow-up via phone or in-person after text-based substance use queries | “I would say the first couple of times through a text but… if it’s getting to [be] an issue or a problem, I’d definitely want a phone call or something just to know that you guys are there.” (Age 36, on PrEP) |

Contingent reinforcement

In concordance with TAM, participants perceived two intended uses of CR messages. First, they considered such messages to be a method for motivating users to maintain adherence to PrEP. CR in the form of positive feedback was viewed by some as a simple way to reinforce desired behavior associated with PrEP adherence. Operationally, participants reported that the greatest potential value of CR messages would be the confirmation that they had correctly operated the DPS, and the reassurance that their ingestion had been recorded; in general, its function as a confirmatory message was reported to be the most desirable use of CR.

Most participants were not in favor of receiving positive feedback following a PrEP ingestion. Participants described PrEP use as a personal choice—a measure taken not only to protect themselves from HIV but also as a demonstration of their commitment to their sexual health—and felt like they did not need any additional rewards for engaging in this behavior.

Participants reported a preference for a neutral, brief CR message indicating that their ingestion was recorded, which would serve to reinforce their DPS use and provide feedback that the system was operated successfully. Participants noted that CR may be most useful early on in PrEP initiation, or among those who had previously struggled with nonadherence. As consistent adherence behaviors become more ingrained, participants reported that CR messages had the potential to become tedious, with some noting that they would prefer weekly CR messages that described aggregate adherence over the past week, rather than daily messages following each individual ingestion. The concept of weekly CR (i.e., as a snapshot of weekly PrEP adherence behavior) was highly acceptable; some participants also described this as a means of facilitating gamification of their PrEP adherence, which could encourage medication-taking behavior.

Corrective feedback

The CF portion of PrEPSteps delivers negative feedback following missed doses of PrEP, as detected by the DPS. Participants widely considered CF messages to be the most helpful intervention component. Perceived benefits included facilitating users’ understanding of PrEP adherence and improving their ability to identify the specific circumstances that increase the likelihood of missing doses, especially when paired with access to their real-time adherence data.

Participants also described other perceived benefits of CF, including that it would help them to recognize potential barriers to nonadherence, as the messages themselves would serve as a reminder of missed PrEP doses. They felt that CF would be an acceptable way for researchers or clinicians to interact with users regarding their nonadherence. Interestingly, some participants reported that CF messages should be obligatory for anyone using the DPS, noting that CF would be an expected component from both a technological standpoint (i.e., CF should be a standard tool for reinforcing adherence in any DPS) and a clinical one (i.e., providers who are monitoring a DPS should be communicating with the patient following evidence of nonadherence).

Similar to CR, most participants agreed that the delivery of CF messages would be important following missed doses. They described CF messages as a helpful way to track nonadherence in the short term and avoid developing patterns of nonadherence in the long term. Many also viewed CF as a means of confirming whether or not a dose had been missed on a given day, thereby reducing potential anxiety and uncertainty. At the same time, some participants reported that CF could be a barrier to DPS use, given the total number of messages one might receive. Despite this, most reported they would still find value in CF, and noted that CF messages should ideally be sent after two or more missed doses in a one-week period.

In terms of the tone and content of CF, most participants preferred messages that were brief and straightforward with a negative tone. This preference for messages with a negative tone (e.g., “You didn’t take your PrEP today. You’re at risk.”) contrasted with the more positive messages that had been presented for discussion in the focus groups (e.g., “You missed your PrEP today. No biggie! Why did it happen?”), which were designed to decrease potential stigma around PrEP nonadherence. Participants reported that the primary purpose of CF messaging should be to alert users of a missed dose (not to console or reassure them) and to compel them to either take their PrEP immediately or to help them remember their pill the next day. In addition, participants suggested that, depending on a user’s preferences, CF could also be an acceptable means of delivering educational messages around HIV and HIV prevention, the benefits of PrEP, and general sexual health information.

LifeSteps boosters

Following a nonadherence event, LifeSteps booster messages linked with CF present a user with several of their self-identified barriers to PrEP adherence; users select the barrier that corresponds to the nonadherence event and is then presented with their personalized solution for that barrier. Many participants reported that the delivery of LifeSteps booster messages in conjunction with CF would be helpful for recognizing the specific reasons for a missed dose, and for remembering the strategies available to them for avoiding nonadherence in the future. The presentation of an individual’s personalized list of adherence barriers from the initial LifeSteps session was viewed as an important facilitator for understanding adherence data from the DPS. Moreover, using participants’ own words to create LifeSteps messages, and prompting them to interact with these messages following nonadherence events, was considered to be an acceptable and effective approach to guiding changes in PrEP adherence behavior.

Two participants perceived the utility of LifeSteps boosters to be limited, noting that the messages would not address the root causes of nonadherence. These participants reported that nonadherent users may not be willing to engage in the self-reflection necessary to identify the reasons for their missed doses; one participant noted that nonadherence would be better addressed at an in-person medical appointment, rather than through a brief mobile intervention. Another suggested that LifeSteps could be a potential avenue for connecting individuals with in-person counseling related to behavioral health issues that may have led to their nonadherence. However, despite this feedback, these participants did not view the presence of LifeSteps booster messages as a barrier to overall interaction with the DPS or the intervention as a whole.

In terms of the content of the LifeSteps booster messages, participants expressed a strong preference for a free text response option that would enable them to identify and report other adherence barriers that they may not have included in their list from the initial LifeSteps session. Participants were largely willing to provide additional details through their responses to the LifeSteps booster messages surrounding their reasons for PrEP nonadherence.

Substance use-related Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment

One goal of the PrEPSteps intervention is to address the intersection of substance use events and nonadherence through messages aimed at improving adherence in this context. The majority of participants reported that a stand-alone SBIRT module that delivered queries around substance use would be too intrusive. While some acknowledged the historical impact of substance use on their PrEP adherence, they maintained that SBIRT messages that attempted to provide encouragement around reducing substance use would be a barrier to interacting with the intervention. Participants also noted that delivering comforting messages around the importance of PrEP adherence in the context of substance use could even have the paradoxical effect of discouraging adherence, as individuals may experience increased guilt or shame associated with substance use-related nonadherence following the receipt of such messages.

While SBIRT was generally perceived as a barrier to interaction with PrEPSteps, some participants recognized the value of such messages. Given the stigma around PrEP nonadherence in this context, substance use messages were recommended to be conciliatory, nonjudgmental, and nonconfrontational in tone, and focusing more on nonadherence than substances, so as not to exacerbate existing mental health conditions, like depression, among DPS users.

Further, while an independent SBIRT module was seen as relatively unacceptable, participants noted that substance use queries could instead be integrated into and explored as part of LifeSteps. Participants were supportive of such app-based querying around substance use and mental health symptoms as adherence barriers and encouraged the inclusion of a mechanism by which users could contact a study team member or other mental health support if needed.

Discussion

PrEP is a pillar of the Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) strategy, and MSM continue to be the population with the greatest risk for HIV acquisition in the US [12]. Moreover, stimulant use has been highly associated with HIV acquisition in MSM [41–44]. Thus, developing an intervention to address PrEP adherence among stimulant users must be a priority. Accurate adherence measures create opportunities to deliver interventions that encourage medication ingestion in the moments that nonadherence occurs. Real-time feedback via the DPS may help MSM with all types of substance use to understand important patterns associated with PrEP adherence and nonadherence. Operation of a DPS system may also promote communication regarding PrEP adherence in real time, providing valuable insights for patients and the opportunity for clinicians and care teams to reinforce adherence [29]. In this investigation, we developed a novel intervention, PrEPSteps, to reinforce adherence to PrEP among MSM with non-alcohol substance use, and leveraged the TAM to solicit qualitative feedback on the intervention and to refine it through a process of iterative modification.

We enacted several key modifications to the PrEPSteps intervention to maximize its acceptance based on focus group discussions. First, participants requested a change in the tone of CR messages. While we had initially conceptualized CR messages as providing encouragement after adherence behavior, participants viewed positively toned messages as unnecessary, and preferred concise, neutral CR messages confirming successful operation of the DPS. Second, participants strongly preferred CF messages that were negative in tone, rather than conciliatory, which was surprising. They described PrEP adherence as an important component of their sexual health and sought negative CF messages that were paired with delivery of information concerning the risks associated with nonadherence. Though we had originally constructed an intervention that was encouraging in response to positive feedback and conciliatory in the face of negative feedback, participants sought less positive feedback and more negative feedback overall; they reported that, if the goal of PrEPSteps was to reinforce PrEP adherence, then messages should be geared towards maximizing adherence and providing strong negative feedback in the face of nonadherence.

One intervention component that was viewed as particularly effective was the LifeSteps booster sessions linked to CF messages. Participants found it acceptable to receive messages, following DPS-detected nonadherence, to help them identify the relevant adherence barriers that may have contributed to their missed dose. This messaging was viewed as increasing the relevance of LifeSteps and enhancing users’ ability to consider their individual barriers in real time. Participants reported a willingness to interact with and respond to LifeSteps booster messages. While participants were also willing to share their experiences with substance use as part of the intervention, and acknowledged its impact on their PrEP adherence, some described substance-use-related messages as intrusive, and asked for such messages to be delivered in a conciliatory tone. They reported that, rather than overemphasizing substance use, messages should remind users that they could still take their PrEP despite having used substances. This important finding may inform the design of future interventions that address substance use among MSM.

Formative qualitative feedback from focus group participants led to several significant changes to the final PrEPSteps intervention (Table 5). First, we adjusted CR messages to a neutrally-toned message (“Ingestion detected”), to be delivered immediately after ingestion; these messages serve as both positive feedback and confirmation that users have correctly operated the DPS. Additionally, at the suggestion of our participants, we added weekly metric messages summarizing the proportion of DPS-detected PrEP doses over the past week as part of the CR module. Second, we combined CF messages with LifeSteps booster messages, such that negative feedback following nonadherence is now presented simultaneously with LifeSteps messages containing user-generated problem-solving solutions to their personal barriers to adherence. Finally, we integrated substance use assessment and counseling into the LifeSteps counseling session to improve its acceptability among potential PrEPSteps users.

Table 5.

| Modifications to original PrEPSteps intervention based on focus group feedback

| Original intervention component | Modifications based on focus group feedback |

|---|---|

| Contingent reinforcement (CR) | • Changed positive/encouraging tone to neutral tone, e.g., “Ingestion detected.”•Added weekly metrics around ingestion, e.g., “This week, you took N/7 doses of PrEP.” |

| Corrective feedback (CF) | • Linked with LifeSteps booster messages |

| LifeSteps boosters | • Simultaneous presentation with CF messages |

| Substance use-related Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) | • Included substance use as a potential barrier to adherence within LifeSteps, rather than as a separate component of the intervention |

This study had several limitations. First, the focus groups were small in size, ranging from one to four individuals; however, we were able to facilitate in-depth discussions of PrEPSteps despite the small group sizes and achieve thematic saturation. Of our focus groups, only one had a single individual in attendance. Given the formative nature of our work, and the novel application of a DPS to PrEP adherence, we felt it was important to incorporate the perspectives shared by this participant. Second, participants were predominately White and well-educated, and therefore their responses may not generalize to members of other demographic groups. We additionally enrolled individuals who were both already maintained on PrEP and those who were interested in starting PrEP. These groups may have differed in willingness to utilize an adherence intervention and preferences regarding key aspects of PrEPSteps. Future research should examine such differences and focus on further tailoring the PrEPSteps intervention based on individual PrEP status and baseline adherence. Finally, this investigation developed and refined the PrEPSteps intervention, but did not deploy the intervention among study participants. The real-world feasibility and acceptability of PrEPSteps, therefore, remains unknown and requires further investigation in the context of a randomized controlled trial.

This investigation demonstrates the use of the TAM to guide the development and refinement of a text message-based behavioral intervention to promote PrEP adherence using data from a DPS. While the TAM is traditionally used to evaluate novel technologies, this study demonstrated that its core tenets can also be applied to behavioral interventions layered on top of the technologies themselves. In particular, we found that the TAM served as a useful framework for assessing prospective users’ perspectives on the utility of PrEPSteps and the perceived methods by which users might interact with PrEPSteps in the real world. This exploration resulted in several important refinements to maximize the acceptability of PrEPSteps; the resulting intervention will be evaluated in a pilot randomized controlled trial (NCT03512418).

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the NIH (grant number K23DA044874).

Contributor Information

Peter R Chai, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, MA, USA; Division of Medical Toxicology, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA; The Koch Institute for Integrated Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Yassir Mohamed, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Georgia Goodman, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Maria J Bustamante, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Matthew C Sullivan, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Jesse Najarro, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Lizette Mendez, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Kenneth H Mayer, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Edward W Boyer, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, MA, USA; Division of Medical Toxicology, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Conall O’Cleirigh, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Rochelle K Rosen, Center for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, The Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI, USA; Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, RI, USA.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: PRC is also funded by NIH R44DA051106 and research funding from Gilead Sciences, Hans and Mavis Psychosocial Foundation, and E-ink Corporation. KM and CO are funded by NIAID P30AI060354. EWB and RKR are funded by NIH R01DA047236.

Human Rights: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Fenway Health (protocol ID 1162312).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Transparency Statements

Study registration: The study was pre-registered at ClinicalTrials.Gov (NCT03512418).

Analytic plan pre-registration: The analysis plan was not formally pre-registered.

Data availability: De-identified data from this study are not available in a public archive. De-identified data from this study will be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) by emailing the corresponding author.

Analytic code availability: There is no analytic code associated with this study.

Materials availability: Materials used to conduct the study are not publicly available.

References

- 1. Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. ; iPrEx Study Team . Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(151):151ra125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Batchelder AW, Safren S, Mitchell AD, Ivardic I, O’Cleirigh C. Mental health in 2020 for men who have sex with men in the United States. Sex Health. 2017;14(1):59–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mayer KH, Skeer MR, O’Cleirigh C, Goshe BM, Safren SA. Factors associated with amplified HIV transmission behavior among American men who have sex with men engaged in care: Implications for clinical providers. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47(2):165–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choi KW, Batchelder AW, Ehlinger PP, Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C. Applying network analysis to psychological comorbidity and health behavior: Depression, PTSD, and sexual risk in sexual minority men with trauma histories. j Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85(12):1158–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Safren SA, Blashill AJ, O’Cleirigh CM. Promoting the sexual health of MSM in the context of comorbid mental health problems. aids Behav. 2011;15(suppl 1):S30–S34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taylor SW, Psaros C, Pantalone DW, et al. “Life-Steps” for PrEP adherence: Demonstration of a CBT-based intervention to increase adherence to Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) medication among sexual-minority men at high risk for HIV acquisition. Cogn Behav Pract. 2017;24(1):38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shuper PA, Joharchi N, Bogoch II, et al. Alcohol consumption, substance use, and depression in relation to HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) nonadherence among gay, bisexual, and other men-who-have-sex-with-men. bmc Public Health. 2020;20(1):1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wood S, Gross R, Shea JA, et al. Barriers and facilitators of PrEP adherence for young men and transgender women of color. aids Behav. 2019;23(10):2719–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chemnasiri T, Varangrat A, Amico KR, et al. ; HPTN 067/ADAPT Study Team . Facilitators and barriers affecting PrEP adherence among Thai men who have sex with men (MSM) in the HPTN 067/ADAPT Study. aids Care. 2020;32(2):249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berry MS, Johnson MW. Does being drunk or high cause HIV sexual risk behavior? A systematic review of drug administration studies. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2018;164:125–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Butler AJ, Rehm J, Fischer B. Health outcomes associated with crack-cocaine use: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:401–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (Updated) (No. Vol. 31). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grov C, Rendina HJ, John SA, Parsons JT. Determining the roles that club drugs, marijuana, and heavy drinking play in PrEP medication adherence among gay and bisexual men: Implications for treatment and research. aids Behav. 2019;23(5):1277–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Biello KB, Psaros C, Krakower DS, et al. A pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence intervention (lifesteps) for young men who have sex with men: Protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. jmir Res Protoc. 2019;8(1):e10661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ching SZ, Wong LP, Said MAB, Lim SH. Meta-synthesis of qualitative research of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence among men who have sex with men (MSM). aids Educ Prev. 2020;32(5):416–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Silapaswan A, Krakower D, Mayer KH. Pre-exposure prophylaxis: A narrative review of provider behavior and interventions to increase PrEP implementation in primary care. j Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):192–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Riddell J 4th, Amico KR, Mayer KH. HIV preexposure prophylaxis: A review. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1261–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qu D, Zhong X, Xiao G, Dai J, Liang H, Huang A. Adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men: A prospective cohort study. Int j Infect Dis. 2018;75:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bell KM, Haberer JE. Actionable adherence monitoring: Technological methods to monitor and support adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Curr hiv/aids Rep. 2018;15(5):388–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Castillo-Mancilla JR, Haberer JE. Adherence measurements in HIV: New advancements in pharmacologic methods and real-time monitoring. Curr hiv/aids Rep. 2018;15(1):49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spinelli MA, Haberer JE, Chai PR, Castillo-Mancilla J, Anderson PL, Gandhi M. Approaches to objectively measure antiretroviral medication adherence and drive adherence interventions. Curr hiv/aids Rep. 2020;17(4):301–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chai PR, Carreiro S, Innes BJ, et al. Digital pills to measure opioid ingestion patterns in emergency department patients with acute fracture pain: a pilot study. j Med Internet Res. 2017;19(1):e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Au-Yeung KY, Moon GD, Robertson TL, et al. Early clinical experience with networked system for promoting patient self-management. Am j Manag Care. 2011;17(7):e277–e287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Belknap R, Weis S, Brookens A, et al. Feasibility of an ingestible sensor-based system for monitoring adherence to tuberculosis therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Browne SH, Peloquin C, Santillo F, et al. Digitizing medicines for remote capture of oral medication adherence using co-encapsulation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(3):502–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Browne SH, Behzadi Y, Littlewort G. Let visuals tell the story: Medication adherence in patients with type II diabetes captured by a novel ingestion sensor platform. jmir Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(4):e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Daar ES, Rosen MI, Wang Y, et al. Real-time and wireless assessment of adherence to antiretroviral therapy with co-encapsulated ingestion sensor in HIV-infected patients: A pilot study. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13(1):189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martani A, Geneviève LD, Poppe C, Casonato C, Wangmo T. Digital pills: A scoping review of the empirical literature and analysis of the ethical aspects. bmc Med Ethics. 2020;21(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chai PR, Goodman G, Bustamante M, et al. Design and delivery of real-time adherence data to men who have sex with men using antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis via an ingestible electronic sensor. aids Behav. 2021;25(6):1661–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bonacini M, Kim Y, Pitney C, McKoin L, Tran M, Landis C. Wirelessly observed therapy to optimize adherence and target interventions for oral hepatitis C treatment: observational pilot study. j Med Internet Res. 2020;22(2):e15532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Frias J, Virdi N, Raja P, Kim Y, Savage G, Osterberg L. Effectiveness of digital medicines to improve clinical outcomes in patients with uncontrolled hypertension and type 2 diabetes: Prospective, open-label, cluster-randomized pilot clinical trial. j Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Knights J, Heidary Z, Cochran JM. Detection of behavioral anomalies in medication adherence patterns among patients with serious mental illness engaged with a digital medicine system. jmir Ment Health. 2020;7(9):e21378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Venkatesh V, Davis FD. A theoretical extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manage Sci. 2000;46(2):186–204. 10.1287/mnsc.46.2.186.11926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Campbell JI, Aturinda I, Mwesigwa E, et al. The Technology Acceptance Model for Resource-Limited Settings (TAM-RLS): A novel framework for mobile health interventions targeted to low-literacy end-users in resource-limited settings. aids Behav. 2017;21(11):3129–3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dworkin MS, Panchal P, Wiebel W, Garofalo R, Haberer JE, Jimenez A. A triaged real-time alert intervention to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among young African American men who have sex with men living with HIV: focus group findings. bmc Public Health. 2019;19(1):394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mayer KH, Safren SA, Elsesser SA, et al. Optimizing pre-exposure antiretroviral prophylaxis adherence in men who have sex with men: Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial of “Life-Steps for PrEP”. aids Behav. 2017;21(5):1350–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL, et al. Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: life-steps and medication monitoring. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39(10):1151–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wong L. Focus group discussion: A tool for health and medical research. Singapore Med J 2008;49:256–60; quiz 261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kinalski DD, Paula CC, Padoin SM, Neves ET, Kleinubing RE, Cortes LF. Focus group on qualitative research: Experience report. Rev Bras Enferm. 2017;70(2):424–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E. Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vu NT, Maher L, Zablotska I. Amphetamine-type stimulants and HIV infection among men who have sex with men: Implications on HIV research and prevention from a systematic review and meta-analysis. j Int aids Soc. 2015;18:19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoenigl M, Chaillon A, Moore DJ, Morris SR, Smith DM, Little SJ. Clear links between starting methamphetamine and increasing sexual risk behavior: A cohort study among men who have sex with men. j Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(5):551–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Santos GM, Coffin PO, Das M, et al. Dose-response associations between number and frequency of substance use and high-risk sexual behaviors among HIV-negative substance-using men who have sex with men (SUMSM) in San Francisco. j Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(4):540–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Freeman P, Walker BC, Harris DR, Garofalo R, Willard N, Ellen JM; Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions 016b Team . Methamphetamine use and risk for HIV among young men who have sex with men in 8 US cities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(8):736–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]