ABSTRACT

The success of islet transplantation in both basic research and clinical settings has proven that cell therapy has the potential to cure diabetes. Islets intended for transplantation are inevitably subjected to damage from a number of sources, including ischemic injury during removal and delivery of the donor pancreas, enzymatic digestion during islet isolation, and reperfusion injury after transplantation in the recipient. Here, we found that protein factors secreted by porcine adipose-tissue mesenchymal stem cells (AT-MSCs) were capable of activating preserved porcine islets. A conditioned medium was prepared from the supernatant obtained by culturing porcine AT-MSCs for 2 days in serum-free medium. Islets were preserved at 4°C in University of Wisconsin solution during transportation and then incubated at 37°C in RPMI-1620 medium with fractions of various molecular weights prepared from the conditioned medium. After treatment with certain fractions of the AT-MSC secretions, the intracellular ATP levels of the activated islets had increased to over 160% of their initial values after 4 days of incubation. Our novel system may be able to restore the condition of isolated islets after transportation or preservation and may help to improve the long-term outcome of islet transplantation.

Abbreviations: AT-MSC, adipose-tissue mesenchymal stem cell; Cas-3, caspase-3; DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DTZ, dithizone; ES cell, embryonic stem cell; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; IEQ, islet equivalent; INS, insulin; iPS cell, induced pluripotent stem cell; Luc-Tg rat, luciferase-transgenic rat; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; PDX1, pancreatic and duodenal homeobox protein-1; UW, University of Wisconsin; ZO1, zona occludens 1.

KEYWORDS: Porcine, islet, mesenchymal stem cells, cold preserved, secreted fractions

Introduction

For patients with type 1 diabetes, islet transplantation is a promising therapy due to its therapeutic effect and safety.1 During islet transplantation, donor islets are infused into the hepatic portal vein, which then engraft to the hepatic parenchyma. In Japan, the islet transplantation program has adopted the immunosuppressive regimen developed by Shapiro et al.2 which is known as the Edmonton Protocol, with the major adaptation that islets are isolated from donors after cardiac death as dictated by the Japanese national protocol for islet donation, isolation, and transplantation.3,4

Clinical islet transplantation can be accomplished in two ways: 1) a cold-preserved brain-dead donor’s pancreas is transported to a cell processing center, where it is then transplanted into a recipient; or 2) a donor pancreas is procured and then the islets are isolated, preserved, cultured, and then transplanted into a recipient in the same facility. For islets to be useful in research and clinical applications, they must maintain their function after shipment from one location to another. It has been reported that the system through which surgeons send procured pancreas to remote islet isolation centers and the center sends back isolated islets is effective within 2,500 km.5–7 According to a recent report, isolated human islets were successfully shipped over 10,000 km internationally, a journey longer than 48 h, with gas-permeable bags being used to maintain clinical grade.8

The success of islet transplantation greatly depends on the number of islets transplanted to the recipient (usually > 13,000 islet equivalent [IEQ]/recipient kg), and insulin independence is generally only achieved after transplantation from more than one donor preparation per recipient.9–11 After intraliver islet transplantation, most recipients achieve insulin independence, but this condition is not permanent.12 Although transplantation of sufficient islets makes it unnecessary for most patients to require insulin administration, the rate of independence decreases over time, with less than 10% of transplant recipients remaining insulin independent at five years.13 It is worthwhile noting that although the liver has been extremely well studied and characterized both in animal models and humans, it is widely recognized that it may not provide the ideal microenvironment for islets due to the immunologic, anatomic, and physiologic factors that contribute to loss of islet mass soon after infusion.14–19

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are thought to be pluripotent cells that can differentiate into a variety of cells and can be an ideal resource for transplantation therapy.20,21 Additionally, MSCs have been confirmed to secrete a variety of cytokines.22

Previously reported, it was suggested that islet co-culture with MSCs are effective in improving the efficiency of clinical islet transplantation.23 From these reports, we considered that there is the islet-suppressing effect that deteriorates during transport and the islet-activating effect before transplantation.

We previously examined the efficacy of several commonly used organ preservation solutions on the viability of isolated islets from luciferase-transgenic (Luc-Tg) rats and found that proteins secreted by rat adipose-tissue mesenchymal stem cells (AT-MSCs) activated preserved Luc-Tg rat islets.24–26

Here, we apply the findings from our rodent model experiments to the preservation and activation of porcine islets in a preclinical study in a large animal. We identified factors secreted from porcine AT-MSCs that markedly activated preserved porcine islets. These data will be helpful for elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms of pancreatic commitment and could be useful in the development of diabetes therapy through the transplantation of preserved islets.

Results

Shipping of porcine islets and establishment of porcine AT-MSCs

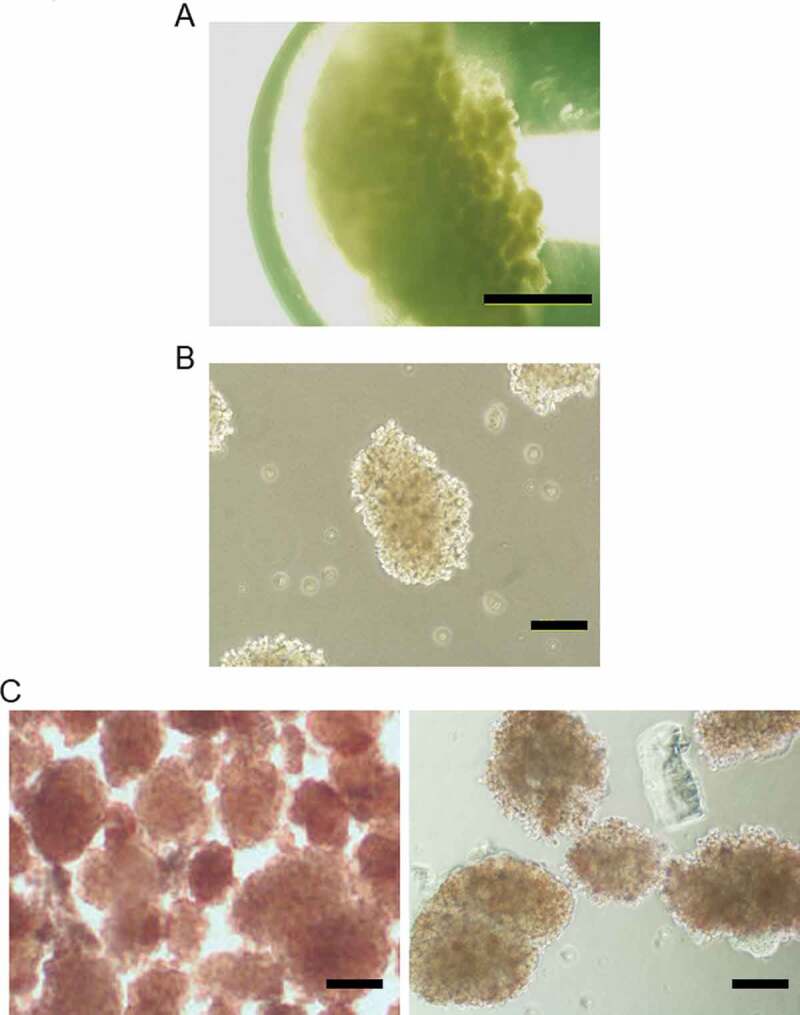

Porcine islets were shipped in University of Wisconsin (UW) preservation solution at 4–10°C in a 1.5-mL tube (about 2,000 IEQ/tube; Figure 1(a)), and the median time required for transportation was 20.3 ± 5.43 h (n = 7). Isolated fresh porcine islets the stimulation index in the static glucose stimulation test (3.482 ± 1.433) and ADP/ATP ratio (0.0518 ± 0.0354) were normally. The islets regained their three-dimensional morphology post-transportation after culturing in RPMI-1620 medium for 2 h (Figure 1(b)), and the survival rate was 66.15% ± 7.08% (n = 7) by trypan blue staining. We found dithizone (DTZ)-negative islets in the samples (Figure 1(c)), suggesting that porcine islets are damaged during shipping by the long preservation time and low temperature.

Figure 1.

Shipping of porcine islets and establishment of porcine adipose-tissue mesenchymal stem cells (AT-MSCs). (a) Phase-contrast image of cold-preserved porcine islets in a 1.5-mL tube. (b) Morphology of porcine islets after 2 h under culture conditions. (c) Dithizone staining of fresh-porcine islets (left) and (b)(Right). (d) Morphology of Kusabira–Orange transgenic porcine-derived AT-MSCs at passage 6. (e) The differentiation potential of porcine AT-MSCs (passage 8) into adipocytes and osteocytes were evaluated using differentiation-induction media purchased from Lonza Walkersville, Inc. (http://www.lonza.com) according the manufacturer’s protocols. (F) Analysis of porcine MSCs marker genes by RT-PCR. Scale bar (a): 1 mm (b), (c), (d), (e): 500 μm.

Figure 1.

Continued.

Next, we isolated porcine AT-MSCs from the fat tissue of Kusabira-Orange transgenic porcines (Figure 1(d)). Established porcine AT-MSCs were induced to differentiate into adipocytes and osteoblasts (Figure 1(e)), and expression of MSC-marker genes was detected by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (CD29+, CD45-, and CD105+), such as a porcine BM-MSCs (Figure 1(f)).27 Thus, our porcine AT-MSCs expressed similar characteristics to those of other animal species, such as rat and human.

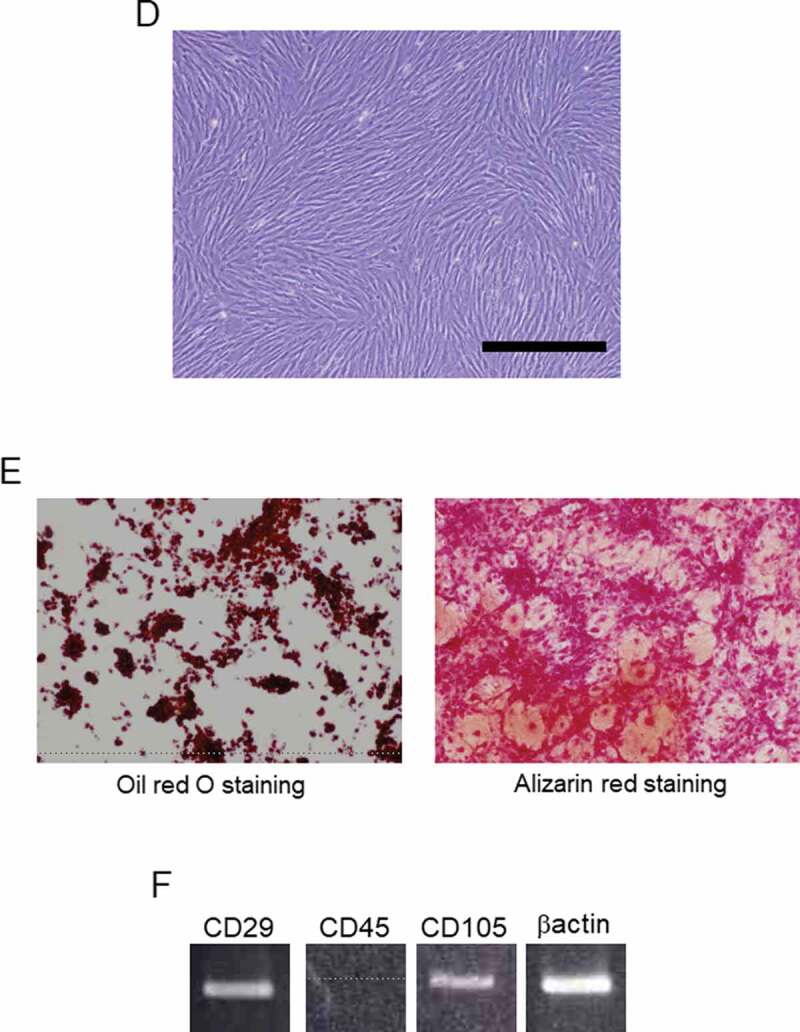

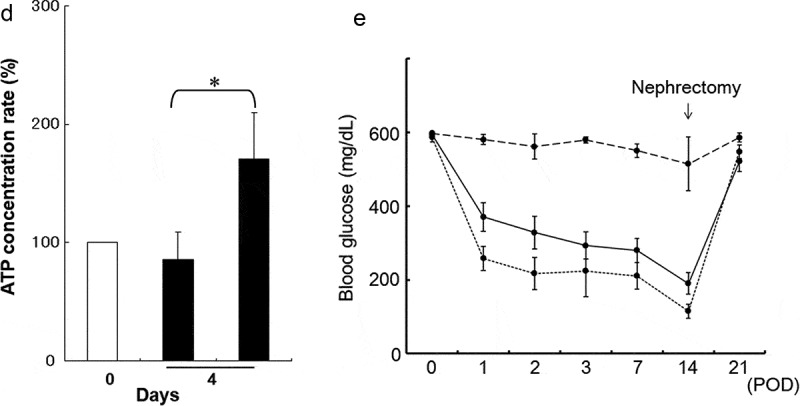

Evaluation of co-culture of degraded porcine islets with porcine AT-MSCs

We used a Boyden chamber to examine the activatory effect of porcine AT-MSCs on degraded porcine islets in co-culture. At 4 days, the co-cultured islets had regained their morphology and strong DTZ positivities (Figure 2(a)); however, the islet-only control group had further degraded (Figure 2(b)). The morphology of the co-cultured MSCs has changed due to the use of serum-free medium (Figure 2(c)). The concentration of intracellular ATP had also recovered in the co-cultured islets (Figure 2(d)), whereas it had not in the islet-only control group (170.7% ± 39.1% vs. 85.4% ± 23.6%). This suggests an important islet activatory role for factors secreted by AT-MSCs.

Figure 2.

Analysis of degraded porcine islets and ATP content in a co-culture system. (a) Co-culture of porcine adipose-tissue mesenchymal stem cells (AT-MSCs) and porcine islets. (b) Islets only. Upper panels are phase-contrast images and bottom panels are images of dithizone staining. (c) The morphology of the co-cultured MSCs. Scale bar (a), (b), (c): 500 µM (d) Intracellular ATP content of co-cultured islets. White bar represents day 0. The black bar on the left represents the islets-only control group on day 4, whereas that on the right represents islets co-cultured with AT-MSCs on day 4. *There are significant differences between the islets-only control group and the islets co-cultured group (P < .05). (e) Blood glucose levels after islet transplantation into the kidney capsule of STZ-induced-diabetic mice are shown. Straight line is UW group. Dashed line is non-transplanted group. Dotted line is UW and AT-MSC secretions group. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Continued.

Functionality of the preserved islet in STZ-induced diabetic mice

Approximately 200 IEQs were transplanted into the left kidney capsule of newly diabetic NOD-scid mice. Mice receiving islets preserved in AT-MSC secretion-conditioned medium in UW or fresh showed better glycemic control than those that received UW only preserved porcine islet (Figure 2(e)). Additionally, a recurrence of hyperglycemia was evident in nephrectomized mice, which suggests that the diabetic condition was reversed upon porcine islet transplantation and reappeared when the graft was removed. Thus, the UW and AT-MSC secretion-conditioned medium preserved islets functioned therapeutically in vivo and their transplantation ameliorated the effects of STZ-induced diabetes in mice.

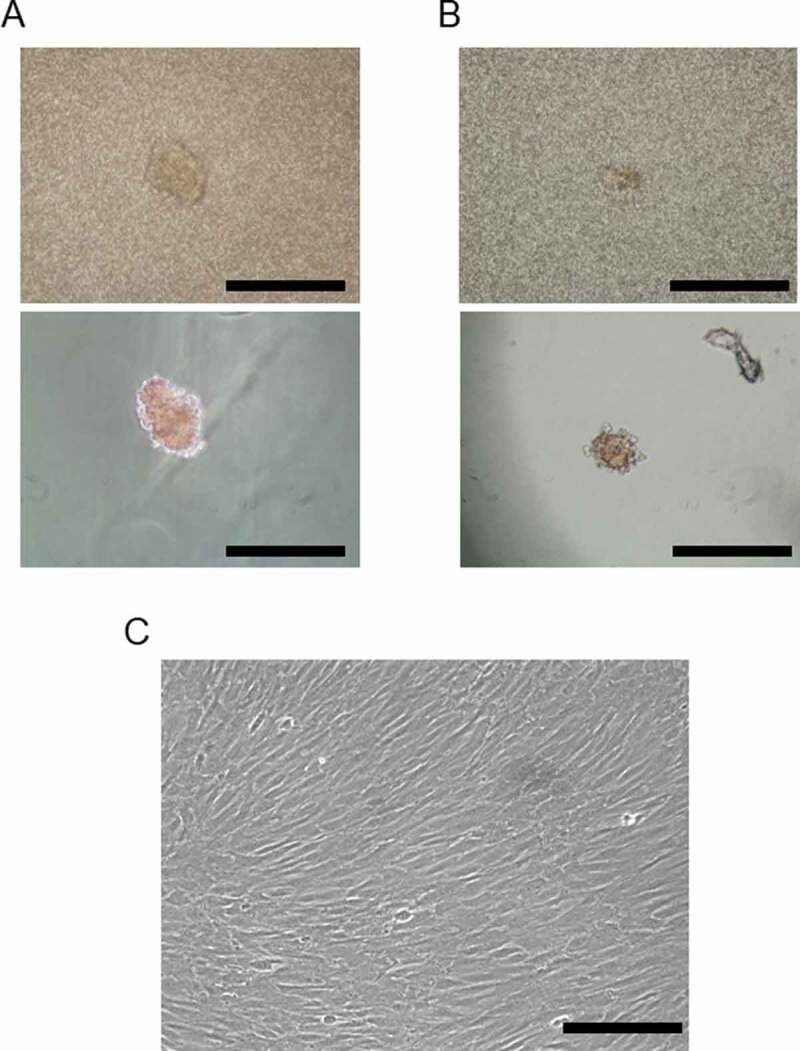

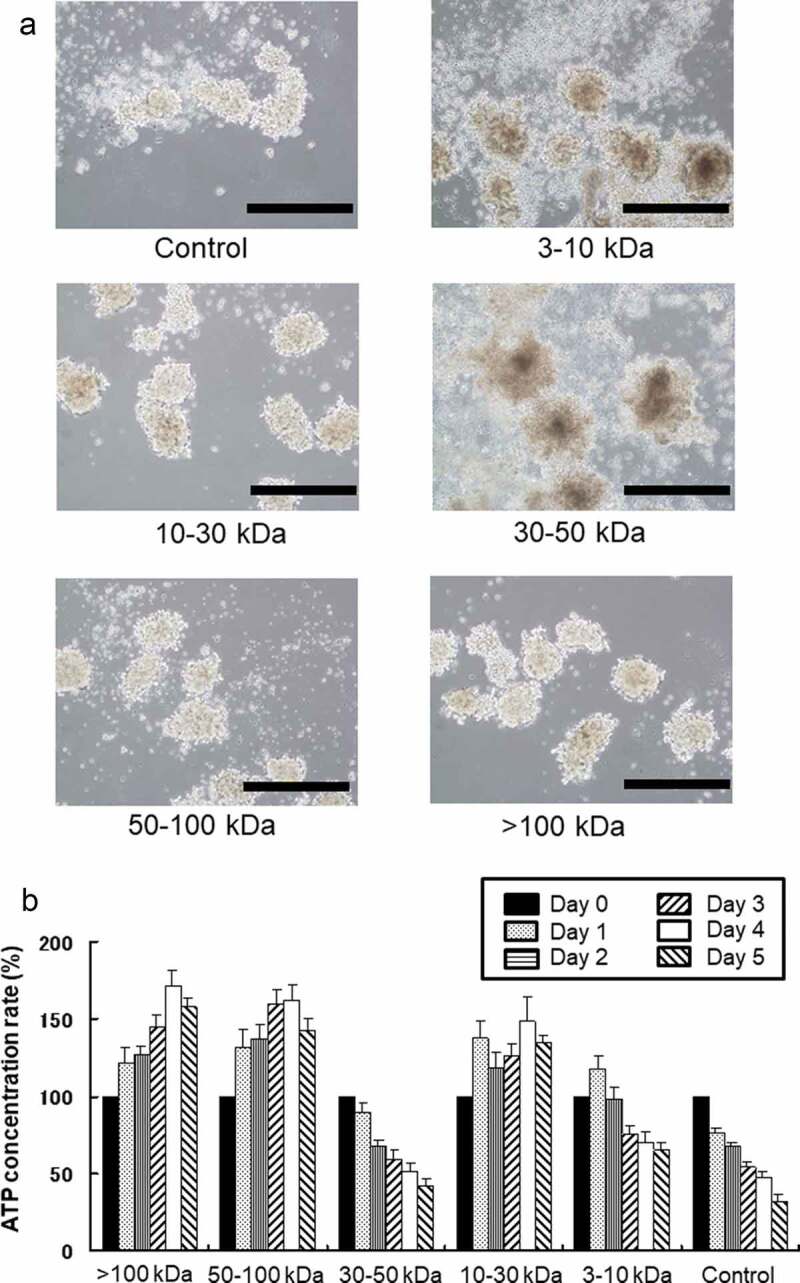

Activation of degraded porcine islets by porcine AT-MSC secretions

We fractionated the AT-MSC secretion-conditioned medium into five fractions by molecular size and treated islet samples with the individual fractions by adding them to the islet culture medium. Islet condition deteriorated when treated with the 3–10 kDa or 30–50 kDa fractions compared with controls (Figure 3(a)). However, when treated with the 10–30 kDa fraction or the fractions above 50 kDa, the islets retained their structure at 4 days. The intracellular ATP content of the cultured islets also recovered in those treated with the 10–30 kDa fraction or the fractions above 50 kDa. However, intracellular ATP content in the groups administered the 3–10 kDa or 30–50 kDa fractions decreased compared with the control group (Figure 3(b)). Thus, we found that factors capable of activating degraded islets were present in the fractions containing secretions with molecular weights between 10 and 30 kDa and above 50 kDa.

Figure 3.

Comparison of porcine islet condition after treatment with various fractions of porcine adipose-tissue mesenchymal stem cell (AT-MSC) secretions. (a) Microscopic morphology of isolated islets after treatment with various fractions of AT-MSC secretions. (b) Intracellular ATP content of each sample of cultured islets after treatment with various fractions of AT-MSC secretions. Intracellular ATP content in the groups administered the 3–10 kDa or 30–50 kDa fractions decreased compared with the control group. Scale bar: 500 µm.

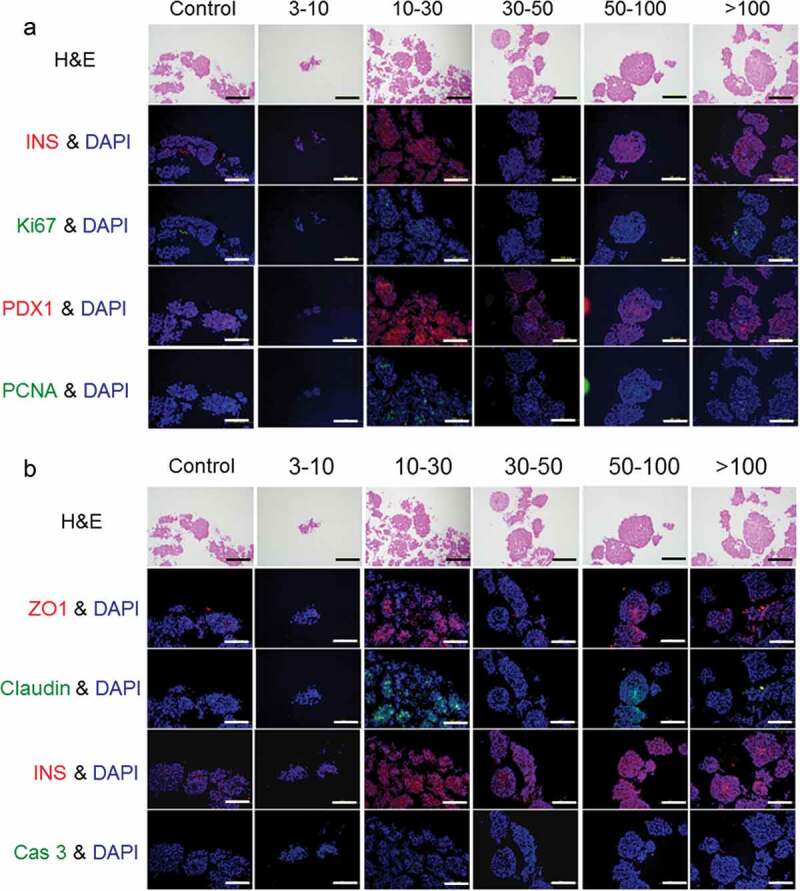

Histological analysis

We analyzed the activation of porcine islets by the factors secreted by AT-MSCs with immunohistochemistry. First, activated porcine islets were stained with markers for functionality (INS and PDX1) and proliferation cells (pancreatic-like stem cells) (Ki67 and PCNA) and then examined under a fluorescence microscope (Figure 4(a)). In the group treated with the 10–30 kDa fraction, we observed a lot of cells strongly positive for INS and PDX1; we also observed some INS- and PDX1-positive cells in the groups treated with the fractions above 50 kDa. In contrast, the numbers of INS- and PDX1-positive cells in the groups treated with the 3–10 kDa and 30–50 kDa fractions were decreased compared with the control group. Ki67- and PCNA-positive cells were observed in the central areas of islets treated with the 10–30 kDa fraction or the fractions above 50 kDa. These positive cells were more abundant in the group treated with the 10–30 kDa fraction. Thus, we found that treatment with fractions containing secretions with molecular weights between 10 and 30 kDa and above kDa increased the expression of markers related to islet function and proliferation.

Figure 4.

Immunostaining of porcine islets activated by various fractions of porcine adipose-tissue mesenchymal stem cells secretions. (a) Evaluation of markers of function and pancreatic stem cells. (b) Evaluation of tight-junction proteins and apoptosis. These samples are serial sections.

Tight junction proteins play an important role in the maintenance of islet structure, so we stained activated porcine islets with anti-ZO1 and anti-Claudin-3 antibodies (Figure 4(b)). In the groups treated with the 10–30 kDa fraction or the fractions above 50 kDa, a stable islet structure was observed together with ZO1 and Claudin-3 expression. However, in the groups treated with the other fractions, ZO1 and Claudin-3 expression was low. In addition, the apoptosis marker Cas-3 was expressed in the groups treated with the 3–10 kDa or 30–50 kDa fraction (Figure 4(b)). Previously reported that PDX-1 negative islet cells have been shown to undergo apoptosis.28

Discussion

Recent reports have focused on the induction of insulin-secreting cells comparable to βαcells from human-derived embryonic stem (ES) cells and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells in vitro.29–32 ES cells and iPS cells have enormous potential; however, limitations, such as teratoma formation followed by tumor genesis and immunogenicity, as well as a range of ethical issues, are preventing them from being applied clinically. Somatic stem cells such as MSCs have also been used to induce insulin-secreting cells in vitro.33,34 MSC-derived insulin-secreting cells present a low risk for tumor genesis and do not raise any ethical issues; however, the clinical application of stem cell-derived insulin-secreting cells is still a long way off. Therefore, patients with severe diabetes are currently treated by through the transplantation of pancreatic tissue or islets from brain-dead donors.

For the quality and quantity of islets from a single donor to be sufficient to cure one recipient in terms of therapeutic effect, the purification rate of isolated islets, and the processes of islet recovery after isolation and maintenance of islet viability must all be improved. To resolve these issues, many researchers have investigated and reported on the use of a range of materials and protocols.35–42 Our method here is little influenced by the condition of the donor pancreas because we use factors secreted by MSCs that restore islets injured during shipping and/or culturing before transplantation. In preliminary experiments (data not shown), we shipped a sample of human islets (n = 1) kept in common preservation solution from the United States to Japan. We then cultured the islets in standard medium containing factors secreted by human MSCs, and the result was similar to that of the present study regarding porcine islets. In Japan, CMRL solution is not so common and only available for clinical shipping. Furthermore, for the islets shipping solution, have been made reports still different from several research facility, it does not have reached the consensus. In our preliminary verification, the UW solution was not inferior to the islets-culture medium (CMRL or equivalent) in storage effectiveness. Additionally, several studies have been reported that experimentally verified the benefits of using UW solution not only for organs but also for islet preservation.43

Cell-based therapy is now viewed as an important tool in regenerative medicine.37,38 Previous reports have revealed that transplantation of MSCs in mice and rats has functional benefits, in part because of the ability of these cells to produce a large amount of bioactive factors.20,21 MSCs display self-renewal capacity and multilineage potential that is they have the potential to differentiate into bone, fat, or cartilage cells44,45 and MSC-like cells have been found in isolated human islets.46,47 Among the numerous molecules that have been proposed to induce β-cell expansion, hepatocyte growth factor has received much attention. There is increasing evidence suggesting that hepatocyte growth factor (about 83 kDa) and insulin-like growth factors (about 29 kDa) play an important role in the proliferation and survival of pancreatic β-cells both in vitro and in vivo.48,49 We think that candidate effectors for activating degraded islets are hepatocyte growth factor, insulin-like growth factor, and the transforming growth factor because previous reports have suggested that these cytokines are factors for the activation of pancreas and/or β cells.50–52

In conclusion, we found that certain fractions of the factors secreted by MSCs were able to activate preserved islets. By using these factors, it should be possible to restore islets to the condition they were in prior to isolation and transportation. This is important for the shipping of islets for research purposes and is even more important for entire islet clinical preparations.

Materials and methods

Animals and islet isolation

Retired breeder porcines weighing approximately 200 kg each were used as donors for all experiments as previously described.53 All animals used in this study were handled in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health.54 Isolation of porcine islets was performed at Tohoku University as previously described,55–57 with minimal modifications. Purified islet fractions were pooled and cultured in CMRL 1066 medium (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 20% porcine serum, 2 mM N-acetyl-L-alanyl-L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 100 IU/mL penicillin (GIBCO, Tokyo, Japan), 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Biochrom), and 20 μg/mL ciprofloxacin (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The medium was subsequently changed to UW solution and the islets translocated to a 1.5-mL Eppndorf tube, which was then put into a Styrofoam container and transported by refrigerated truck to Jichi Medical University, Tochigi, Japan. The porcine islets take about 20 hours to refrigerate and transport the isolated to the Jichi Medical University.

Adipose tissue-derived MSC preparation and culture

Kusabira-Orange transgenic porcine-derived adipose tissue was minced with scissors and scalpels into pieces less than 1 mm in diameter. After gentle shaking of the minced tissue with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS[–]), the mixture was separated into two phases. The upper phase (the phase containing stem cells, adipocytes, and blood) was enzymatically dissociated with 0.125% collagenase (type I) in PBS[–] for 1.5 h at 37°C with gentle shaking. The dissociated tissue was mixed with an equal volume of MEMα (GIBCO, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Tokyo, Japan), and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The solution was left to separate into two phases in a few minutes. The lower phase was centrifuged at 1,200 rpm for 5 min at 20°C to isolate the AT-MSCs. The AT-MSCs were then seeded into 100-mm tissue culture dishes (Thermo Scientific, Tokyo) and cultured in MEMα supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. When the cells were 70% to 80% confluent, they were harvested with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen, Tokyo), replated at 2.0 × 104 cells/cm2, and cultured in MEMα supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C for 5 days. AT-MSCs between the fifth and eighth passages were used for the experiments.

Characterization of porcine AM-MSCs

Analysis of stem cell markers genes and differentiation ability in porcine AT-MSCs. Total RNA (0.5 g) was reverse-transcribed using the SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. PCR analyses were performed using the AmpliTaq Gold kit (Applied Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan). The PCR primer sequences are listed in Table 1. The differentiation potential of porcine AT-MSCs (passage 8) into adipocytes and osteocytes was evaluated using differentiation-induction media purchased from Lonza Walkersville, Inc. (http://www.lonza.com) according the manufacturer’s protocols.

Table 1.

Primer list

| Primer Name | Accession No | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| CD29 Forward | NM213968 | 5ʹ-ACAGTGAAGACATGGACGCT-3’ |

| CD29 Reveres | 5ʹ-CAGGTCTGACACATCTCACA-3’ | |

| CD45 Forward | AY444866 | 5ʹ-TCCAGAATGCGTCACTCTGA-3’ |

| CD45 Reveres | 5ʹ-TTGAATGTGAGGCAGACTCC-3’ | |

| CD105 Forward | NM214031 | 5ʹ-CTTTGTGCAGGTGAGCATGT-3’ |

| CD105 Reveres | 5ʹ-TGCAGTCTTGTGGACATCCA-3’ | |

| βActin Forward | NM007393 | 5ʹ-AGAGCAAGAGAGGTATCCTG-3’ |

| βActin Reveres | 5ʹ-GCAGAAGCCTAGTTGGATCA-3’ |

Production of conditioned medium

To analyze the factors secreted by AT-MSCs, we prepared a conditioned medium. AT-MSCs were plated into thirty 100-mm tissue culture dishes. Once they had reached confluence, the cells were washed with PBS[–] and incubated in serum-free MEMααmedium (GIBCO). After 2 days, the supernatant was collected and then centrifuged, filtered, and concentrated at 12,000 rpm using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (Millipore, Tokyo, Japan; molecular weights 3, 10, 30, 50, and 100 kDa).

Immunohistochemical analysis of preserved islets

Islet samples were cultured for 4 days at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, before being fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Histological analysis was conducted by serial tissue section followed by staining with hematoxylin and eosin for conventional morphological evaluation or with anti-INS-1 (sc-7839, Dilute 150 times), anti-PDX-1 (sc-14662, Dilute 150 times), anti-Ki67 (E1870, Dilute 200 times), anti-PCNA (sc-7970, Dilute 200 times), anti-ZO1 (HP9044, Dilute 100 times), or anti-Claudin-3 (sc-17662, Dilute 100 times) antibodies. Rhodamine- or FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies were applied for 30 min (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dilute 2000 times). Nuclei were stained with DAPI.

Measurement of ATP

ATP was measured by means of an ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit CLS II (Roche Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was measured with a Mithras LB940 multimode microplate reader (Berthold, Tokyo, Japan). The total amount of ATP was normalized for total protein level using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (TaKaRa, Kyoto, Japan).

Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice

STZ (Sigma, Tokyo, Japan) was prepared in citrate buffer (pH4.5) and delivered by intraperitoneal injection (50 mg/kg) for 5 consecutive days before transplantation. Mice with blood glucose levels >400 mg/dl were considered as diabetic.

Analysis of preserved porcine islets for diabetic mice

The porcine islets were cultured in preservation solution (UW contacting AT-MSC secretion-conditioned medium or UW only) at 4°C. After 24 h, preserved islets were injected under the kidney capsule. An incision was made in the renal capsule and advanced in the subcapsular space, to the kidney. Isolated porcine islets were slowly injected and allowed to spread at the pole. The blood glucose level was checked at days 0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, and 21. After 14 days, the prince islet containing transplanted kidney was resected, and monitoring of blood glucose continued 7 days.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Results were analyzed by using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the personnel in the Division of Development of Advanced Therapy, Jichi Medical University.

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Duality of interest

The authors state that they have no duality of interest.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: TT and YF

Performed the experiments: TT, NK, MG

Analyzed the data: TT, NK, YS

Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: TT, MG, NK, AM, NS, JK.

Wrote the paper: TT

References

- 1.Barton FB, Rickels MR, Alejandro R, Hering BJ, Wease S, Naziruddin B, Oberholzer J, Odorico JS, Garfinkel MR, Levy M, et al. Improvement in outcomes of clinical islet transplantation: 1999-2010. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(7):1436–1445. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan EA, Lakey JR, Rajotte RV, Korbutt GS, Kin T, Imes S, Rabinovitch A, Elliott JF, Bigam D, Kneteman NM, et al. Clinical outcomes and insulin secretion after islet transplantation with the edmonton protocol. Diabetes. 2001;50(4):710–719. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.4.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, Korbutt GS, Toth E, Warnock GL, et al. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(4):230–238. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saito T, Gotoh M, Satomi S, Uemoto S, Kenmochi T, Itoh T, Kuroda Y, Yasunami Y, Matsumoto S, Teraoka S, et al. Islet transplantation using donors after cardiac death: report of the Japan Islet Transplantation Registry. Transplantation. 2010;90(7):740–747. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ecb044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langer RM, Máthé Z, Doros A, Máthé ZS, Weszelits V, Filó A, Bucher P, Morel P, Berney T, Járay J, et al. Successful islet after kidney transplantations in a distance over 1000 kilometres: preliminary results of the Budapest-Geneva collaboration. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(10):3113–3115. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ichii H, Sakuma Y, Pileggi A, Fraker C, Alvarez A, Montelongo J, et al. Shipment of human islets for transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1010–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabkin JM, Leone JP, Sutherland DE, Ahman A, Reed M, Papalois BE, Wahoff DC.. Transcontinental shipping of pancreatic islets for autotransplantation after total pancreatectomy. Pancreas. 1997;15(4):416–419. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199711000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikemoto T, Matsumoto S, Itoh T, Noguchi H, Tamura Y, Jackson AM, et al. Assessment of islet quality following international shipping of more than 10,000 km. Cell Transplant. 2010;19(6–7):731–741. doi: 10.3727/096368910X508834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ricordi C, Strom TB. Clinical islet transplantation: advances and immunological challenges. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(4):259–268. doi: 10.1038/nri1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goto M, Eich TM, Felldin M, Foss A, Källen R, Salmela K, Tibell A, Tufveson G, Fujimori K, Engkvist M, et al. Refinement of the automated method for human islet isolation and presentation of a closed system for in vitro islet culture. Transplantation. 2004;78(9):1367–1375. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000140882.53773.DC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan EA, Shandro T, Green K, Paty BW, Senior PA, Bigam D, Sgapiro AMJ, Vantyghem M-C. Assessment of the severity of hypoglycemia and glycemic lability in type 1 diabetic subjects undergoing islet transplantation. Diabets. 2004;53(4):955–962. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennet W, Groth CG, Larsson R, Nilsson B, Korsgren O. Isolated human islets trigger an instant blood mediated inflammatory reaction: implications for intraportal islet transplantation as a treatment for patients with type 1 diabetes. Ups J Med Sci. 2000;105(2):125–133. doi: 10.1517/03009734000000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan EA, Paty BW, Senior PA, Bigam D, Alfadhli E, Kneteman NM, Lakey JRT, Shapiro AMJ. Five-year follow-up after clinical islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2005;54(7):2060–2069. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melzi R, Sanvito F, Mercalli A, Andralojc K, Bonifacio E, Piemonti L. Intrahepatic islet transplant in the mouse: functional and morphological characterization. Cell Transplant. 2008;17(12):1361–1370. doi: 10.3727/096368908787648146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toyofuku A, Yasunami Y, Nabeyama K, Nakano M, Satoh M, Matsuoka N, Ono J, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Tanaka M, et al. Natural killer T-cells participate in rejection of islet allografts in the liver of mice. Diabetes. 2006;55(1):34–39. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.01.06.db05-0692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yasunami Y, Kojo S, Kitamura H, Toyofuku A, Satoh M, Nakano M, et al. Valpha14 NK T cell-triggered IFN-gamma production by Gr-1+CD11b+ cells mediates early graft loss of syngeneic transplanted islets. J Exp Med. 2005;202(7):913–918. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlsson PO, Palm F, Andersson A, Liss P. Markedly decreased oxygen tension in transplanted rat pancreatic islets irrespective of the implantation site. Diabetes. 2001;50(3):489–495. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korsgren O, Lundgren T, Felldin M, Foss A, Isaksson B, Permert J, Persson NH, Rafael E, Rydén M, Salmela K. Optimising islet engraftment is critical for successful clinical islet transplantation. Diabetologia. 2008;51(2):227–232. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0868-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriksson O, Eich T, Sundin A, Tibell A, Tufveson G, Andersson H, et al. Positron emission tomography in clinical islet transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(12):2816–2824. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banas A, Teratani T, Yamamoto Y, Tokuhara M, Takeshita F, Osaki M, et al. IFATS collection: in vivo therapeutic potential of human adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells after transplantation into mice with liver injury. Stem Cells. 2008;26(10):2705–2712. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanazawa H, Fujimoto Y, Teratani T, Iwasaki J, Kasahara N, Negishi K, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in a rat model. PLoS One. 2011;29(4):e19195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishikawa T, Banas A, Teratani T, Iwaguro H, Ochiya T. Regenerative cells for transplantation in hepatic failure. Cell Transplant. 2012;21(2–3):387–399. doi: 10.3727/096368911X605286b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rackham CL, Dhadda PK, Le Lay AM, King AJ, Jones PM. Preculturing Islets With Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Is an Effective Strategy for Improving Transplantation Efficiency at the Clinically Preferred Intraportal Site. Cell Med. 2014;7(1):37–47. doi: 10.3727/215517914X680047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Negishi K, Teratani T, Iwasaki J, Kanazawa H, Kasahara N, Lefor AT, et al. Luminescence technology in preservation and transplantation for rat islet. Islets. 2011;3(3):111–117. doi: 10.4161/isl.3.3.15626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teratani T, Matsunari H, Kasahara N, Nagashima H, Kawarasaki T, Kobayashi E. Islets from rats and porcines transgenic for photogenic proteins. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2012;8(5):382–389. doi: 10.2174/157339912802083504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasahara N, Teratani T, Doi J, Iijima Y, Maeda M, Uemoto S, et al. Use of mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium to activate islets in preservation solution. Cell Med. 2013;5(2–3):75–81. doi: 10.3727/215517913X666477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juhásová J, Juhás S, Klíma J, Strnádel J, Holubová M, et al. Osteogenic differentiation of miniature porcine mesenchymal stem cells in 2D and 3D environment. Physiol Res. 2011;60:111–117. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson JD, Ahmed NT, Luciani DS, Han Z, Tran H, Fujita J, Misler S, Edlund H, Polonsky KS. Increased islet apoptosis in Pdx1± mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(8):1147–1160. doi: 10.1172/JCI200316537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Amour KA, Bang AG, Eliazer S, Kelly OG, Agulnick AD, Smart NG, et al. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1392–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang J, Au M, Lu K, Eshpeter A, Korbutt G, Fisk G, Majumdar AS. Generation of insulin-producing islet-like clusters from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25(8):1940–1953. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang D, Jiang W, Liu M, Sui X, Yin X, Chen S, et al. Highly efficient differentiation of human ES cells and iPS cells into mature pancreatic insulin-producing cells. Cell Res. 2009;19(4):429–438. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thatava T, Nelson TJ, Edukulla R, Sakuma T, Ohmine S, Tonne JM, Yamada S, Kudva Y, Terzic A, Ikeda Y, et al. Indolactam V/GLP-1-mediated differentiation of human iPS cells into glucose-responsive insulin-secreting progeny. Gene Ther. 2011;18(3):283–293. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsai PJ, Wang HS, Lin GJ, Chou SC, Chu TH, Chuan WT, Lu Y-J, Weng Y-J, Su C-H, Hsieh P-S, et al. Undifferentiated Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation Induces Insulin-Producing Cell Differentiation and Suppression of T-Cell-Mediated Autoimmunity in Nonobese Diabetic Mice. Cell Transplant. 2015;24(8):1555–1570. doi: 10.3727/096368914X683016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim SY, Kim YR, Park WJ, Kim HS, Jung SC, Woo SY, Jo I, Ryu K-H, Park J-W. Characterisation of insulin-producing cells differentiated from tonsil derived mesenchymal stem cells. Differentiation. 2015;90(1–3):27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Omori K, Valiente L, Orr C, Rawson J, Ferreri K, Todorov I, Al-Abdullah IH, Medicherla S, Potter AA, Schreiner GF, et al. Improvement of human islet cryopreservation by a p38 MAPK inhibitor. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(5):1224–1232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omori K, Mitsuhashi M, Ishiyama K, Nair I, Rawson J, Todorov I, Kandeel F, Mullen Y. mRNA of the pro-apoptotic gene BBC3 serves as a molecular marker for TNF-α-induced islet damage in humans. Diabetologia. 2011;54(8):2056–2066. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCall MD, Maciver AH, Pawlick R, Edgar R, Shapiro AM. Histopaque provides optimal mouse islet purification kinetics: comparison study with ficoll, iodixanol and dextran. Islets. 2011;3(4):144–149. doi: 10.4161/isl.3.4.15729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kin T, Shapiro AM. Surgical aspects of human islet isolation. Islets. 2010;2(5):265–273. doi: 10.4161/isl.2.5.13019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimoda M, Itoh T, Sugimoto K, Iwahashi S, Takita M, Chujo D, SoRelle JA, Naziruddin B, Levy MF, Grayburn PA, et al. Improvement of collagenase distribution with the ductal preservation for human islet isolation. Islets. 2012;4(2):130–137. doi: 10.4161/isl.19255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friberg AS, Brandhorst H, Buchwald P, Goto M, Ricordi C, Brandhorst D, Korsgren O. Quantification of the islet product: presentation of a standardized current good manufacturing practices compliant system with minimal variability. Transplantation. 2011;91(6):677–683. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31820ae48e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saito Y, Goto M, Maya K, Ogawa N, Fujimori K, Kurokawa Y, Satomi S. Brain death in combination with warm ischemic stress during isolation procedures induces the expression of crucial inflammatory mediators in the isolated islets. Cell Transplant. 2010;19(6–7):775–782. doi: 10.3727/096368910X508889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noguchi H, Naziruddin B, Onaca N, Jackson A, Shimoda M, Ikemoto T, et al. Comparison of modified Celsior solution and M-kyoto solution for pancreas preservation in human islet isolation. Cell Transplant. 2010;19(6–7):751–758. doi: 10.3727/096368909X508852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noguchi H, Naziruddin B, Jackson A, Shimoda M, Ikemoto T, Fujita Y, Chujo D, Takita M, Kobayashi N, Onaca N, et al. Low-temperature preservation of isolated islets is superior to conventional islet culture before islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;89(1):47–54. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181be3bf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stb H, Tanavde VM, Hui JH, Lee EH. Upregulation of adipogenesis and chondrogenesis in MSC serum-free culture. Cell Med. 2011;2(2):27–41. doi: 10.3727/215517911X575984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Sci. 1999;284(5411):143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlotti F, Zaldumbide A, Loomans CJ, van Rossenberg E, Engelse M, de Koning EJ, Hoeben RC. Isolated human islets contain a distinct population of mesenchymal stem cells. Islets. 2010;2(3):164–173. doi: 10.4161/isl.2.3.11449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson LM, Wong SH, Yu N, Geras-Raaka E, Raaka BM, Gershengorn MC. Insulin but not glucagon gene is silenced in human pancreas-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27(11):2703–2711. doi: 10.1002/stem.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alvarez-Perez JC, Ernst S, Demirci C, Casinelli GP, Mellado-Gil JM, Rausell-Palamos F, Vasavada RC, Garcia-Ocaña A. Hepatocyte growth factor/c-Met signaling is required for β-cell regeneration. Diabetes. 2014;63(1):216–223. doi: 10.2337/db13-0333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agudo J, Ayuso E, Jimenez V, Salavert A, Casellas A, Tafuro S, Haurigot V, Ruberte J, Segovia JC, Bueren J, et al. IGF-I mediates regeneration of endocrine pancreas by increasing beta cell replication through cell cycle protein modulation in mice. Diabetologia. 2008;51(10):1862–1872. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Izumida Y, Aoki T, Yasuda D, Koizumi T, Suganuma C, Saito K, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor is constitutively produced by donor-derived bone marrow cells and promotes regeneration of pancreatic beta-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333(1):273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park SM, Hong SM, Sung SR, Lee JE, Kwon DY. Extracts of Rehmanniae radix, Ginseng radix and Scutellariae radix improve glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and beta-cell proliferation through IRS2 induction. Genes Nutr. 2008;2(4):347–351. doi: 10.1007/s12263-007-0065-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han B1, Qi S, Hu B, Luo H, Wu J. TGF-beta I promotes islet beta-cell function and regeneration. J Immunol. 2011;186(10):5833–5844. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goto M, Tjernberg J, Dufrane D, Elgue G, Brandhorst D, Ekdahl KN, Brandhorst H, Wennberg L, Kurokawa Y, Satomi S, et al. Dissecting the instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction in islet xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15(4):225–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bayne K. Revised Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals available. Am Phys Soc Physiolo. 1996;39:208–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goto M, Groth CG, Nilsson B, Korsgren O. Intraportal porcine islet xenotransplantation into athymic mice as an in vivo model for the study of the instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11(2):195–202. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-3089.2003.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dendo M, Maeda H, Yamagata Y, Murayama K, Watanabe K, Imura T, et al. Synergistic Effect of Neutral Protease and Clostripain on Rat Pancreatic Islet Isolation. Transplantation. 2015;99:1349–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goto M, Holgersson J, Kumagai-Braesch M, Korsgren O. The ADP/ATP ratio: a novel predictive assay for quality assessment of isolated pancreatic islets. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(10):2483–2487. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]