ABSTRACT

The emergence of daptomycin-resistant (DAP-R) Staphylococcus aureus strains has become a global problem. Point mutations in mprF are the main cause of daptomycin (DAP) treatment failure. However, the impact of these specific point mutations in methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains associated with DAP resistance and the “seesaw effect” of distinct beta-lactams remains unclear. In this study, we used three series of clinical MRSA strains with three distinct mutated mprF alleles from clone complexes (CC) 5 and 59 to explore the seesaw effect and the combined effect of DAP plus beta-lactams. Through construction of mprF deletion and complementation strains of SA268, we determined that mprF-S295A, mprF-S337L, and one novel mutation of mprF-I348del within the bifunctional domain lead to DAP resistance. Compared with wild-type mprF cloned from a DAP-susceptible (DAP-S) strain, these three mprF mutations conferred the seesaw effect to distinct beta-lactams in the SA268ΔmprF strains, and mutated mprF (I348del and S337L) did not alter the cell surface positive charge (P > 0.05). The susceptibility to beta-lactams increased significantly in DAP-R CC59 strains, and the seesaw effect was found to be associated with distinct mutated mprF alleles and the category of beta-lactams. The synergistic activity of DAP plus oxacillin was detected in all DAP-R MRSA strains. Continued progress in understanding the mechanism of restoring susceptibility to beta-lactam antibiotics mediated by the mprF mutation and its impact on beta-lactam combination therapy will provide fundamental insights into treatment of MRSA infections.

KEYWORDS: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, daptomycin, mprF, seesaw effect, beta-lactams, treatment, MRSA

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the major causes of hospital and community-acquired infections. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) accounts for at least 25% to 50% of S. aureus infections in hospital settings, resulting in serious consequences, including central line-associated bloodstream infections, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis (1, 2). Daptomycin (DAP) or vancomycin (VAN) monotherapy is the recommended first line of treatment for MRSA bacteremia (3). Owing to the limited tissue distribution and emergence of isolates with reduced susceptibility to VAN, DAP has become an important alternative therapy targeting MRSA infections (4).

DAP is a cyclic lipopeptide approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in a wide variety of S. aureus infections, such as bloodstream infections (BSI) and endocarditis. However, clinical S. aureus strains with mprF mutations, especially MRSA, have been reported to be associated with DAP treatment failures. These mutations involve altering surface charge, cell wall thickness, and cell membrane synthesis (5–8). Most studies have investigated mprF functions in clinical strains and have not evaluated other mutations in genes influencing mprF, which have been associated with the DAP-resistant (DAP-R) phenotype, such as yycFG, rpoB, rpoC, pgsA, and cls (9). Thus, it is necessary to study mprF mutations in a defined genetic background. Yang et al. showed that the S. aureus (Newman) strain mprF deletion mutant exhibited increased susceptibility to DAP, and mprF-S295L and mprF-T345A increased the DAP MIC and net surface positive charge (10).

The “seesaw effect” describes a phenomenon in which DAP resistance sensitizes MRSA to beta-lactams, which has been observed both in vitro and in vivo (11–14). Some researchers have shown that the mprF mutation could contribute to beta-lactam sensitization, which is involved in the effectiveness of DAP-oxacillin (OXA) combination (15). Furthermore, various studies have revealed that combinations of DAP with nafcillin (NAF) (in vivo), as well as other beta-lactams, displayed strong synergistic interactions against DAP resistance in MRSA isolates (11). However, it has been demonstrated that the mprF mutation does not always correlate with enhanced OXA susceptibility (10, 16). Thus, it remains to be elucidated whether all mprF mutations could restore susceptibility to beta-lactam antibiotics and the mechanism by which mutated mprF influences the effectiveness of the DAP-beta-lactam combination against DAP-R MRSA.

In a previous study, we collected 20 sequential clinical DAP-S and DAP-R MRSA isolates from three infective endocarditis patients (5). In this study, we investigated the impact of the specific mutations of mprF genes on susceptibility to DAP and beta-lactams in vitro. We aimed to evaluate the synergistic effects of DAP in combination with OXA against MRSA strains with different mprF mutations using the time-kill assay. This research provides new insights for the development of effective treatments for MRSA infection.

RESULTS

Distinct point mutations in mprF lead to DAP resistance.

In our previous studies, different mutations (S295A, I348del, and S337L) on mprF genes were detected in DAP-R MRSA isolates. All three mutations are located at the junction of the flippase domain and the synthase domain of MprF (5). To elucidate the contribution of distinct mprF mutations to DAP resistance in a defined genetic background, each mutation was cloned into a plasmid and then transferred to the S. aureus strain SA268ΔmprF. Phenotypic analysis comparing SA268 and its isogenic SA268ΔmprF showed that the inactivation of mprF led to increased susceptibility to DAP; the MIC decreased from 0.5 μg/ml to 0.0625 μg/ml (Table 1). Furthermore, complementation of SA268ΔmprF with wild-type mprF (Δ-pmprFSA268) and respective parental mprF (Δ-pmprFSAZ1, Δ-pmprFSAW1, and Δ-pmprFSAC1) restored the susceptibility to DAP (MIC, 0.5 μg/ml). Importantly, three mutants complemented with mprF containing S295A, I348del, or S337L mutations (Δ-pmprFS295A, Δ-pmprFI348del, and Δ-pmprFS337L) revealed higher DAP resistance, with MICs of 2, 4, and 4 μg/ml, respectively, compared to their isogenic mutants complemented with mprF from DAP-susceptible (DAP-S) strains. Thus, these results indicated that these three mprF mutations confer DAP resistance in S. aureus.

TABLE 1.

MICs of DAP and beta-lactams for SA268 and mprF derivatives

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) of: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAP | FOX | OXA | CZ | AMO | PEN | |

| SA268 | 0.5 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| SA268-p | 0.25 | 64 | 64 | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| ΔmprF | 0.0625 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| ΔmprF-p | 0.125 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| Δ-pmprFSA268 | 0.5 | 128 | 64 | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| Δ-pmprFSAZ1 | 0.5 | 128 | 32 | 64 | 16 | 4 |

| Δ-pmprFS295A | 2 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 2 |

| Δ-pmprFSAW1 | 0.5 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 8 |

| Δ-pmprFI348del | 4 | 32 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| Δ-pmprFSAC1 | 0.5 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| Δ-pmprFS337L | 4 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

There was no significant impact of the mprF deletion and point mutations on the MICs of other non-beta-lactam antibiotics, such as quinolones, macrolides, and glycopeptides (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Contribution of mprF mutations to the seesaw effect.

The beta-lactam MICs were measured to investigate the association between the seesaw effect and the mprF mutations from DAP-R strains. All 20 clinical DAP-S and DAP-R MRSA isolates were resistant to cefoxitin (FOX), OXA, and penicillin (PEN), except for SAC4A and SAC4B, which exhibited susceptibility to OXA at an MIC of 0.5 μg/ml (see Table 2). Although there were no breakpoints for amoxicillin (AMO) and cefazolin (CZ) in the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, we observed that the beta-lactam MICs of all SAZ strains that belonged to clone complex (CC) 5 were higher than that of the other three CC59 MRSA strains. Furthermore, compared with their isogenic DAP-S strains, the susceptibility to beta-lactams increased significantly among SAW5 with mprF-I348del and SAC4A and SAC4B with mprF-S337L, whereas SAZ7 (DAP = 2 μg/ml) with mprF-S295A did not influence the phenotypic variability of beta-lactams. In particular, the beta-lactam MICs of SAC4A/B declined by ≥4-fold. For example, the MIC of OXA declined from 32 μg/ml to 0.5 μg/ml, and the AMO MIC declined from 16 μg/ml to 2 μg/ml, suggesting that CC59 strains with the mprF mutation displayed the seesaw effect, whereas the SAZ7 (CC5) strain did not.

TABLE 2.

MICs of DAP and beta-lactams for clinical MRSA isolates

| Strain | CC | ST/SCC meca | MIC (μg/ml) of: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAP | FOX | OXA | CZ | AMO | PEN | |||

| SAZ1 | 5 | 5/II | 0.25 | 1024 | 2048 | 512 | 64 | 32 |

| SAZ2 | 5 | 5/II | 0.25 | 1024 | 2048 | 512 | 64 | 32 |

| SAZ3 | 5 | 5/II | 0.25 | 1024 | 2048 | 512 | 64 | 32 |

| SAZ4 | 5 | 5/II | 0.5 | 1024 | 2048 | 512 | 32 | 32 |

| SAZ5 | 5 | 5/II | 0.5 | 1024 | 2048 | 512 | 32 | 32 |

| SAZ6 | 5 | 5/II | 0.5 | 1024 | 2048 | 512 | 64 | 32 |

| SAZ7 | 5 | 5/II | 2 | 1024 | 2048 | 512 | 32 | 32 |

| SAW1 | 59 | 59/IVa | 0.25 | 32 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 16 |

| SAW2 | 59 | 59/IVa | 0.25 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 |

| SAW3 | 59 | 59/IVa | 0.5 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 |

| SAW4 | 59 | 59/IVa | 0.5 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 16 |

| SAW5 | 59 | 59/IVa | 1b | 16 | 32 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| SAC1 | 59 | 4513/IVa | 0.125 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 4 |

| SAC2 | 59 | 4513/IVa | 0.25 | 32 | 32 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| SAC3 | 59 | 4513/IVa | 0.5 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 16 |

| SAC4A | 59 | 4513/IVa | 4 | 8 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 |

| SAC4B | 59 | 4513/IVa | 4 | 16 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 |

| SAC5A | 59 | 4513/IVa | 0.25 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 16 | 8 |

| SAC5B | 59 | 4513/IVa | 0.25 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 16 | 8 |

| SAC5C | 59 | 4513/IVa | 0.25 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 16 |

ST, sequence type; SCC mec, staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec.

The MIC of SAW5 was 2 μg/ml irregularly.

To determine whether the mprF point mutations contributed to the seesaw effect, we measured the susceptibility of different beta-lactams in the mprF deletion and complementation MRSA strains. The SA268ΔmprF resulted in increased susceptibility to beta-lactams such as FOX, OXA, and CZ with a ≥4-fold decrease in MICs (Table 1). The strains of Δ-pmprFSA268 restored beta-lactam susceptibility compared to SA268, indicating that the mprF gene impacted beta-lactam susceptibility in SA268. Compared with strains carrying parental mprF (Δ-pmprFSAW1 and Δ-pmprFSAC1), the mutants complemented with two mutated mprF (Δ-pmprFI348del and Δ-pmprFS337L) genes produced significant increases in susceptibility to OXA and CZ, as evidenced by a ≥4-fold decline in MICs. The MIC of Δ-pmprFS295A decreased 4-fold in CZ. Moreover, the susceptibility of PEN and AMO was not significantly changed (≤2-fold) among these strains, indicating that the seesaw effect was variable among distinct beta-lactams.

In vitro activity of DAP-OXA combinations against DAP-S/DAP-R MRSA strains.

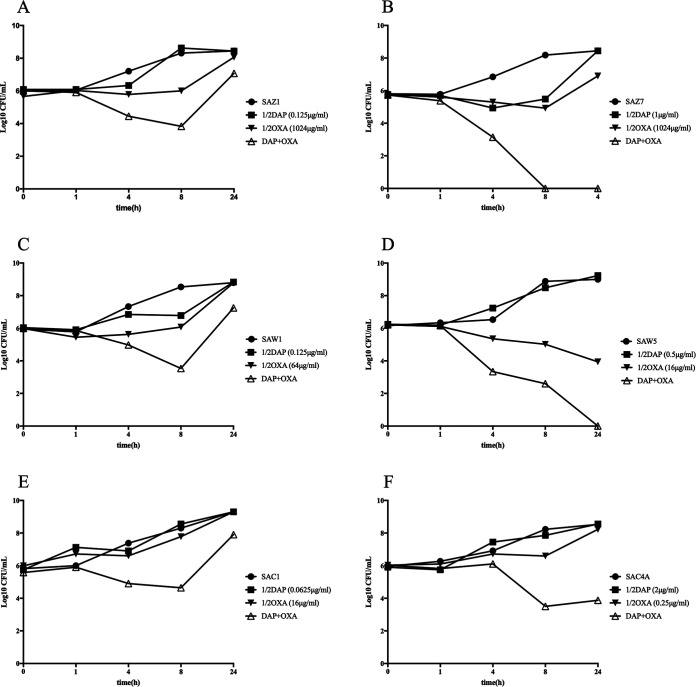

Previous observations showed that DAP, in combination with beta-lactams, exhibits significant synergistic effects (17–19). Thus, the time-killing test was performed to investigate whether our clinical DAP-S/DAP-R MRSA strains have a similar phenotype in the presence of 1/2× MIC of DAP and OXA. As shown in Fig. 1A to F, after 24 h of incubation with DAP and OXA, synergistic activity was observed in three DAP-R strains (SAZ7, SAW5, and SAC4A), as demonstrated by strain killing of ≥2-log10 CFU/ml at 24 h compared with the initial inoculum and the most active single agents. Furthermore, the curves demonstrated a dramatic killing starting in the first 8 h. In contrast, all DAP-S MRSA strains were unaffected by the combination of DAP and OXA, with change in killing being <2-log10 CFU/ml. Thus, the combination of DAP and OXA may have a major impact on DAP-R MRSA strains. In addition, our results revealed this combination is equally effective for strains without the seesaw effect.

FIG 1.

In vitro time-kill curves for 7 clinical MRSA strains. Time-kill analyses were performed using MH broth with a 106 CFU/ml inoculum at 0, 1, 4, 8, and 24 h in 1/2× MIC of DAP and OXA. (A, C, and E) DAP-S MRSA strains. (B, D, F, and G) DAP-R MRSA strains.

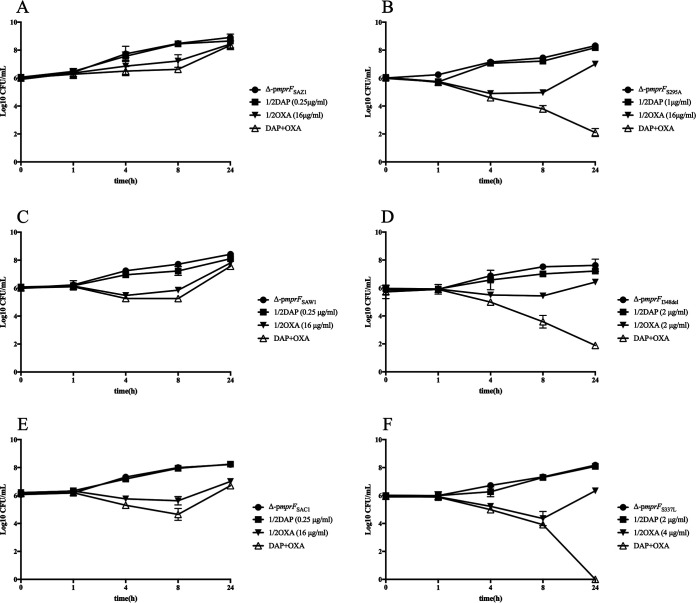

To further investigate the effect of this combination, in vitro time-kill curves for its respective parental mprF- and mutated mprF-complemented strains were performed (Fig. 2). Similar to the previous results, neither DAP nor OXA used alone showed any bactericidal effects. After 24 h, the combination of DAP and OXA demonstrated indifference to all wild-type mprF-complemented strains, with the differences in counts < 2-log10 CFU/ml change in killing. However, the mprF-mutated strains showed a downward growth, and count decreased ≥2-log10 CFU/ml compared with those of the single agents and the initial inoculum, suggesting that the combination of DAP and OXA is highly synergistic in killing mprF mutant strains.

FIG 2.

In vitro time-kill curves for mprF-mutated and -complemented strains. Time-kill analyses were performed using MH broth with a 106 CFU/ml inoculum at 0, 1, 4, 8, and 24 h in 1/2× MIC of DAP and OXA. (A, C, and E) Wild-type mprF-complemented strains derived from three clinical DAP-S MRSA strains. (B, D, and F) Mutated mprF-complemented strains derived from three clinical DAP-R MRSA strains.

Effect of mprF mutations on cell surface positive charge and cell wall thickness.

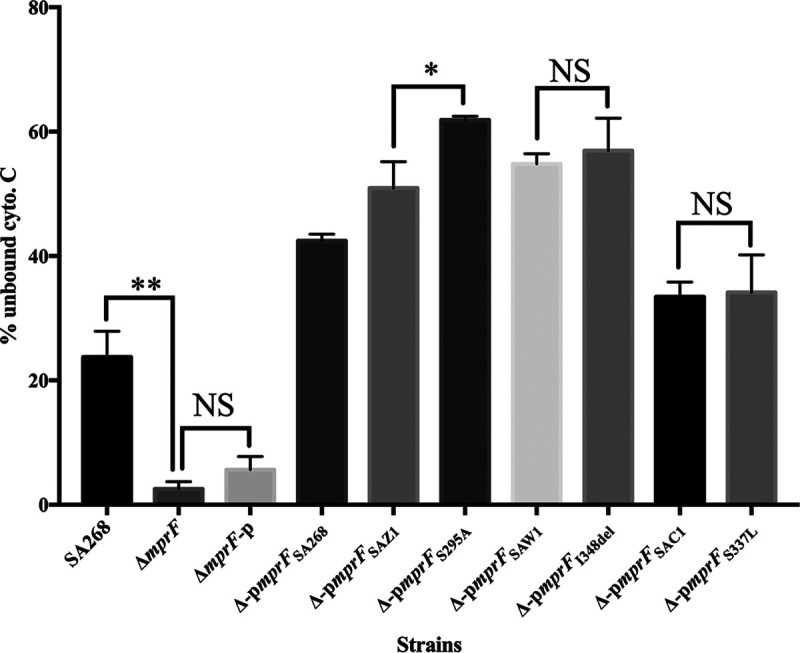

To analyze whether the point mutations in mprF could affect the overall S. aureus surface charge, we compared the cytochrome c-binding capacities of strains expressing mprF to those of the wild-type or mutated strains. As shown in Fig. 3, the SA268ΔmprF had a significantly reduced positive surface charge compared to that of the SA268 strain (P ≤ 0.01). Of note, the percentage of unbound cytochrome c of the strain carrying an mprF mutation (S295A) was higher than the strain complemented with its wild-type mprF (P ≤ 0.05). However, the other two DAP resistance-associated mutations (I348del and S337L) did not impact the positive surface charges (P > 0.05) compared with the parental mprF gene. Thus, these results indicate that not all the DAP resistance-associated mprF mutations lead to alteration of the cell surface positive charge.

FIG 3.

Binding of cytochrome c to SA268 and its mprF derivates. Data represent the means (±SDs) from three independent experiments. **, P ≤ 0.01; *, P ≤ 0.05; NS, P > 0.05.

Furthermore, there were no significant increases in cell wall thickness in clinical DAP-R strains compared to the respective DAP-S strain (P > 0.05) (see Fig. S1).

DISCUSSION

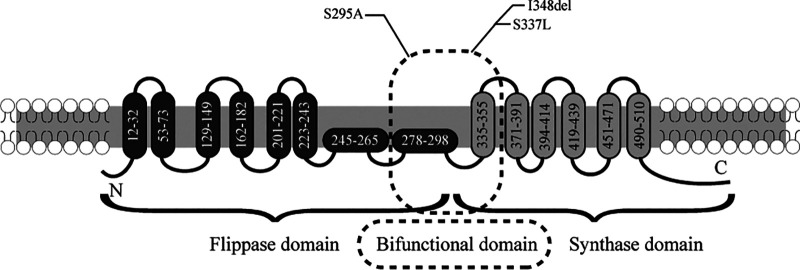

MRSA is responsible for the increased disease burden, and in recent years, it has rapidly disseminated among the general population in most areas, including China (20, 21). Resistance to DAP is an emerging clinical problem in the treatment of MRSA infections such as bacteremia and endocarditis. Recently, it has been demonstrated that mprF mutations located at a central bifunctional domain bridging the synthase and translocase domains play a crucial role in MprF function (6, 16, 22). In this study, we determined that mutated mprF genes at S295A and S337L and one novel mutation, I348del, which is located at the junction of the flippase and synthase domains, derived from clinical strains, could mediate DAP resistance (Fig. 4). Notably, our results indicated that change of cell surface charge and cell wall thickness did not necessarily occur in mprF-mutated strains. Some studies have reported the association of increased cell positive charge with mprF mutations (10, 23). However, increasing evidence suggests that DAP resistance-conferring point mutations in mprF do not lead to a general alteration of the cell surface charge and cell wall thickness (24). The membrane lipids need to be evaluated in the future to better understand the phenotypic membrane adaptations in these mprF-mutated strains. Mechanistically, the T345A mutation in mprF may enable the flippase to accommodate DAP, conferring DAP resistance (16).

FIG 4.

MprF topology analysis. Specific mutations within the bifunctional domain bridging the flippase and the synthase domains of MprF mediate daptomycin resistance. The MprF synthase and flippase domains are shown in gray and black, respectively. The predicted MprF topology was modified from previous publications (6, 16).

Novel combinations of last-resort antibiotics like DAP or VAN with beta-lactams have been recommended for the treatment of MRSA infections because beta-lactam susceptibility may improve when lipopeptide or glycopeptide susceptibility is decreased (25, 26). Mutated mprF is a key component of the seesaw effect that results in impairment of PrsA location and chaperone functions, which are essential for penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a) maturation (15). Consistent with previous reports, we determined the contribution of S295A, I348del, and S337L mutations in mprF to the seesaw effect in a defined genetic background of ST59 MRSA. We also observed that this effect was associated with distinct mprF alleles, showing that mprF-I348del and mprF-S337L had a higher beta-lactam susceptibility than mprF-S295A. We also noticed that only some beta-lactams, such as OXA and CZ, showed resensitization in mprF-mutated strains, suggesting the seesaw effect is mainly achieved by beta-lactams targeting the different PBPs. On the other hand, we found the seesaw effect was relatively significant in CC59 strains since two CC59 strains exhibited restored susceptibility to beta-lactams. This might be explained by the diversity in the genetic background of the strain. Some researchers have observed that the strains which express a high level of beta-lactam resistance do not display the seesaw effect (11, 15). Thus, we emphasized that the seesaw effect was limited to specific mutations in mprF, distinct beta-lactams, and genetic background.

Many studies suggest that DAP plus beta-lactam in addition to standard monotherapy against MRSA strains demonstrates a synergistic effect both in vitro and in vivo (27, 28). Several mechanisms have been reported explaining synergistic activity of beta-lactams combined with DAP. Mechanistically, beta-lactams enhanced the activity of DAP against DAP-R MRSA strains by inducing a reduction in the cell surface positive charge, increasing the frequency of septation and cell wall abnormalities, boosting the immune system, and reducing virulence (11, 29, 30). Our study showed that DAP combined with OXA also had synergistic activity, not only in CC59 MRSA strains but also in CC5 strains without the seesaw effect. However, the concentration of OXA used in a synergistic assay for this CC5 MRSA was high, and the clinical efficacy of this combination should be further studied in vivo, especially for MRSA lineages with high beta-lactam MICs.

There are some limitations to our study. First, only mutations in the mprF gene were investigated in the present study. Previous studies showed that multiple genes and pathways were involved in the DAP resistance mechanism and seesaw effect. Here, we constructed mprF mutants in an ST59 strain and confirmed the important role of mprF in the seesaw effect. Second, only three series of clinical MRSA were included in this study, which may not be representative of all the phenotypes for these lineages. Further study, including more diverse CCs and strains, should be conducted. However, the data on the seesaw effect in CC5 and CC59 MRSA are important since they both belong to the predominant clones in mainland China. Finally, only cell surface charge and cell wall thickness were analyzed, which may not fully help us understand the gain-in-function mutations in the mprF gene. More cell membrane phenotypic assays need to be investigated in the future.

To conclude, though the combination of DAP with beta-lactams is recommended to enhance the therapeutic effect for infections such as endocarditis (31), our study illustrated that the efficacy of DAP and beta-lactam combination therapy was strain or clone dependent. Therefore, continued progress in understanding the mechanism of restoring susceptibility to beta-lactam antibiotics mediated by the mprF mutation and its impact on beta-lactam combination therapy will provide fundamental insights into treatment of MRSA infections such as bacteremia and endocarditis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 3. Twenty sequential MRSA strains were isolated from blood cultures of three endocarditis patients as previously described and investigated in this study (5). The wild-type S. aureus SA268 strain, which belongs to ST59, was used for constructing mprF mutants. Strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Oxoid, Cambridge, UK) or on tryptic soy agar (TSA; Oxoid, Cambridge, UK) plates unless specified.

TABLE 3.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| SAZ1 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST5-CC5, SAZ7 with mutation of S295A in mprF | 5 |

| SAZ2 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST5-CC5, SAZ7 with mutation of S295A in mprF | 5 |

| SAZ3 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST5-CC5, SAZ7 with mutation of S295A in mprF | 5 |

| SAZ4 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST5-CC5, SAZ7 with mutation of S295A in mprF | 5 |

| SAZ5 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST5-CC5, SAZ7 with mutation of S295A in mprF | 5 |

| SAZ6 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST5-CC5, SAZ7 with mutation of S295A in mprF | 5 |

| SAZ7 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST5-CC5, SAZ7 with mutation of S295A in mprF | 5 |

| SAW1 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST59-CC59, SAW5 with mutation of I348del in mprF | 5 |

| SAW2 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST59-CC59, SAW5 with mutation of I348del in mprF | 5 |

| SAW3 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST59-CC59, SAW5 with mutation of I348del in mprF | 5 |

| SAW4 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST59-CC59, SAW5 with mutation of I348del in mprF | 5 |

| SAW5 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST59-CC59, SAW5 with mutation of I348del in mprF | 5 |

| SAC1 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST4513-CC59, SAC4A, and SAC4B with mutation of S337L in mprF | 5 |

| SAC2 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST4513-CC59, SAC4A, and SAC4B with mutation of S337L in mprF | 5 |

| SAC3 | Clinically derived MRSA, ST4513-CC59, SAC4A, and SAC4B with mutation of S337L in mprF | 5 |

| SAC4A | Clinically derived MRSA, ST4513-CC59, SAC4A, and SAC4B with mutation of S337L in mprF | 5 |

| SAC4B | Clinically derived MRSA, ST4513-CC59, SAC4A, and SAC4B with mutation of S337L in mprF | 5 |

| SAC5A | Clinically derived MRSA, ST4513-CC59, SAC4A, and SAC4B with mutation of S337L in mprF | 5 |

| SAC5B | Clinically derived MRSA, ST4513-CC59, SAC4A, and SAC4B with mutation of S337L in mprF | 5 |

| SAC5C | Clinically derived MRSA, ST4513-CC59, SAC4A, and SAC4B with mutation of S337L in mprF | 5 |

| SA268 | CA-MRSA, ST59 | 39 |

| ΔmprF | SA268, deleted mprF | This study |

| SA268-p | SA268 strain complementing pTX16 | This study |

| ΔmprF-p | SA268ΔmprF strain complementing pTX16 | This study |

| Δ-pmprFSA268 | SA268ΔmprF strain expressing mprF cloned from SA268 | This study |

| Δ-pmprFSAZ1 | SA268ΔmprF strain expressing mprF cloned from SAZ1 | This study |

| Δ-pmprFS295A | SA268ΔmprF strain expressing S295A mutation in mprF compared with SAZ1 | This study |

| Δ-pmprFSAW1 | SA268ΔmprF strain expressing mprF cloned from SAW1 | This study |

| Δ-pmprFI348del | SA268ΔmprF strain expressing I348del mutation in mprF compared with SAW1 | This study |

| Δ-pmprFSAC1 | SA268ΔmprF strain expressing mprF cloned from SAC1 | This study |

| Δ-pmprFS337L | SA268ΔmprF strain expressing S337L mutation in mprF compared with SAC1 | This study |

| Escherichia coli DH5α | Host strain for construction of recombination plasmids | |

| RN4220 | A descendant of S. aureus NCTC 8325 employed as a subcloning host | 40 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKOR1 | E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector plasmid | 32 |

| pTXΔ | S. aureus plasmid derived from pTX15, Tetr | 33 |

| pTX16 | Control plasmid for pTX expression plasmid series, lipase gene present in pTX15 is deleted | 41 |

Gene deletion and complementation.

Gene deletion mutants were constructed as previously described (32). Briefly, allelic replacement was performed by amplifying approximately 1-kb regions up- and downstream of the gene(s) and cloning them into plasmid pKOR1. The plasmi d was first transformed into S. aureus RN4220 and then into strain SA268. To integrate the plasmid, SA268 (pKOR1-mprF) cultures grown at 30°C in TSB with 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol (TSBCm10) were transferred into fresh TSBCm10, prewarmed at 43°C, and incubated overnight with rotation at the same temperature. The deletion mutant was verified using PCR and sequencing.

Wild-type and mutated derivatives of mprF were cloned in pTXΔ and transferred into strain SA268ΔmprF (33). Briefly, mprF was amplified using PCR, digested with BamHI and MluI, cloned into BamHI- and MluI-digested pTXΔ, and transformed into S. aureus RN4220 and then into the SA268ΔmprF strains via electroporation. These plasmids confer resistance to tetracycline, which was added to growth cultures at a concentration of 12.5 mg/ml. Parental SA268 and SA268ΔmprF strains bearing the empty plasmid pTX16 were used as controls. Primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Oligonucleotide sequences were confirmed using Sanger sequencing.

Determination of susceptibility to beta-lactams and other non-beta-lactams.

The MICs of daptomycin (DAP), cefoxitin (FOX), cefazolin (CZ), oxacillin (OXA), gentamicin (GEN), ciprofloxacin (CIP), rifampin (RIP), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SMT), clindamycin (CLI), linezolid (LZ), tetracycline (TET), levofloxacin (LEV), erythromycin (ERY), vancomycin (VAN), and teicoplanin (TEC) were determined with broth microdilution in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (34) ([CLSI]) 2019 guidelines. The MICs of penicillin (PEN) and amoxicillin (AMO) were determined by agar dilution and Iso-Sensitest agar (TopBio, China) as previous study described (35). The terms resistant or resistance are used to describe decreased susceptibility, whether or not the MIC reached the clinically relevant breakpoint levels.

Isolate pairs with a positive seesaw effect were defined by a ≥4-fold decrease in beta-lactam MIC in the DAP-R strain compared to its respective parental DAP-S strain (36).

Analysis of synergy combined with DAP and beta-lactams.

Time-kill curves were determined with DAP and OXA at concentrations of 1/2× MIC, using MH broth containing 50 μg/ml Ca2+ with an initial inoculum of 1 × 106 CFU/ml according to previously described criteria (11, 37). Viability counts were performed at 0, 1, 4, 8, and 24 h. Bactericidal synergy was defined as a ≥2-log10 CFU/ml decrease between the combination antibiotic and the most active single agent after 24 h. Moreover, the number of surviving organisms in the presence of the combination had to be ≥2-log10 CFU/ml below the starting inoculum. Lack of difference was defined as a <2-log10 change (increase or decrease) in killing. All experiments were performed in duplicate. Data analysis was performed using Prism 7.0 software.

Phenotypic analysis.

To quantify relative cell surface charge in strains, we employed the cytochrome c binding assays as previously characterized (16, 38). Briefly, exponential-phase bacteria were harvested, washed twice with MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0), and adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1. Aliquots of 1 ml were collected, resuspended in 200 μl MOPS buffer and 50 μl of cytochrome c solution (equine heart, 2.5 mg/ml in MOPS buffer; Sigma), and incubated at 37°C with shaking for 15 min. Supernatants were recovered, and the OD530 was measured spectrophotometrically. Data shown for assays are the means (±standard deviations [SDs]) of three independent experiments.

To determine the cell wall thickness of the DAP-S and DAP-R strains, S. aureus cells were prepared for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (TECNAI-10; Philips) analyses as described previously (24). For each strain, 50 cell wall thickness measurements were obtained from a minimum of 25 cells at ×205,000 magnification (Gatan charge-coupled device [CCD]).

Ethics.

This study was approved by the local ethics committees of Sir Run Shaw Hospital with a waiver of informed consent (approval no. 20190426-2).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Otto (U.S. National Institutes of Health) and Min Li (Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine) for providing the plasmids pKOR1 and pTXΔ. We thank Beibei Wang in the Center of Cryo-Electron Microscopy (CCEM), Zhejiang University, for her technical assistance in transmission electron microscopy.

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (project no. LQ20H190005) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project no. 81971977).

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Shengnan Jiang, Yunsong Yu, and Yan Chen designed the study. Hemu Zhuang, Feiteng Zhu, Xiang Wei, and Junxiong Zhang did experiments. Lu Sun, Shujuan Ji, Haiping Wang, Dandan Wu, Feng Zhao, and Rushuang Yan analyzed the data. Shengnan Jiang, Hemu Zhuang, Yunsong Yu, and Yan Chen wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Yunsong Yu, Email: yvys119@zju.edu.cn.

Yan Chen, Email: chenyan@zju.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lakhundi S, Zhang K. 2018. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: molecular characterization, evolution, and epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Rev 31:e00020-18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00020-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindsay JA, Holden MT. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus: superbug, super genome? Trends Microbiol 12:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassoun A, Linden PK, Friedman B. 2017. Incidence, prevalence, and management of MRSA bacteremia across patient populations-a review of recent developments in MRSA management and treatment. Crit Care 21:211. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1801-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Micek ST. 2007. Alternatives to vancomycin for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Clin Infect Dis 45(Suppl 3):S184–90. doi: 10.1086/519471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji S, Jiang S, Wei X, Sun L, Wang H, Zhao F, Chen Y, Yu Y. 2020. In-host evolution of daptomycin resistance and heteroresistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from three endocarditis patients. J Infect Dis 221:S243–S252. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayer AS, Mishra NN, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Rubio A, Yang SJ. 2015. Frequency and distribution of single-nucleotide polymorphisms within mprF in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates and their role in cross-resistance to daptomycin and host defense antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4930–4937. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00970-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards RL, Haigh RD, Pascoe B, Sheppard SK, Price F, Jenkins D, Rajakumar K, Morrissey JA. 2015. Persistent Staphylococcus aureus isolates from two independent cases of bacteremia display increased bacterial fitness and novel immune evasion phenotypes. Infect Immun 83:3311–3324. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00255-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphries RM, Pollett S, Sakoulas G. 2013. A current perspective on daptomycin for the clinical microbiologist. Clin Microbiol Rev 26:759–780. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00030-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller WR, Bayer AS, Arias CA. 2016. Mechanism of action and resistance to daptomycin in Staphylococcus aureus and enterococci. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 6:a026997. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang SJ, Mishra NN, Rubio A, Bayer AS. 2013. Causal role of single nucleotide polymorphisms within the mprF gene of Staphylococcus aureus in daptomycin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5658–5664. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01184-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta S, Singh C, Plata KB, Chanda PK, Paul A, Riosa S, Rosato RR, Rosato AE. 2012. Beta-lactams increase the antibacterial activity of daptomycin against clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains and prevent selection of daptomycin-resistant derivatives. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:6192–6200. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01525-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang SJ, Xiong YQ, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum R, Jones T, Bayer AS. 2010. Daptomycin-oxacillin combinations in treatment of experimental endocarditis caused by daptomycin-nonsusceptible strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with evolving oxacillin susceptibility (the “seesaw effect”). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3161–3169. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00487-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhand A, Bayer AS, Pogliano J, Yang SJ, Bolaris M, Nizet V, Wang G, Sakoulas G. 2011. Use of antistaphylococcal beta-lactams to increase daptomycin activity in eradicating persistent bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: role of enhanced daptomycin binding. Clin Infect Dis 53:158–163. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moise PA, Amodio-Groton M, Rashid M, Lamp KC, Hoffman-Roberts HL, Sakoulas G, Yoon MJ, Schweitzer S, Rastogi A. 2013. Multicenter evaluation of the clinical outcomes of daptomycin with and without concomitant beta-lactams in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and mild to moderate renal impairment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1192–1200. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02192-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renzoni A, Kelley WL, Rosato RR, Martinez MP, Roch M, Fatouraei M, Haeusser DP, Margolin W, Fenn S, Turner RD, Foster SJ, Rosato AE. 2017. Molecular bases determining daptomycin resistance-mediated resensitization to beta-lactams (seesaw effect) in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01634-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01634-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernst CM, Slavetinsky CJ, Kuhn S, Hauser JN, Nega M, Mishra NN, Gekeler C, Bayer AS, Peschel A. 2018. Gain-of-function mutations in the phospholipid flippase MprF confer specific daptomycin resistance. mBio 9:e01659-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01659-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kebriaei R, Rice SA, Singh NB, Stamper KC, Nguyen L, Sheikh Z, Rybak MJ. 2020. Combinations of (lipo)glycopeptides with beta-lactams against MRSA: susceptibility insights. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:2894–2901. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steenbergen JN, Mohr JF, Thorne GM. 2009. Effects of daptomycin in combination with other antimicrobial agents: a review of in vitro and animal model studies. J Antimicrob Chemother 64:1130–1138. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karchmer AW. 2021. Combination therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia: beauty remains in the eye of the beholder. Clin Infect Dis 72:1526–1528. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.David MZ, Daum RS. 2010. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin Microbiol Rev 23:616–687. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Sun L, Ba X, Jiang S, Zhuang H, Zhu F, Wang H, Lan P, Shi Q, Wang Z, Chen Y, Shi K, Ji S, Jiang Y, Holmes MA, Yu Y. 2021. Epidemiology, evolution and cryptic susceptibility of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in China: a whole-genome-based survey. Clin Microbiol Infect doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayer AS, Mishra NN, Sakoulas G, Nonejuie P, Nast CC, Pogliano J, Chen KT, Ellison SN, Yeaman MR, Yang SJ. 2014. Heterogeneity of mprF sequences in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates: role in cross-resistance between daptomycin and host defense antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:7462–7467. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03422-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thitiananpakorn K, Aiba Y, Tan XE, Watanabe S, Kiga K, Sato'o Y, Boonsiri T, Li FY, Sasahara T, Taki Y, Azam AH, Zhang Y, Cui L. 2020. Association of mprF mutations with cross-resistance to daptomycin and vancomycin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Sci Rep 10:16107. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73108-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang SJ, Nast CC, Mishra NN, Yeaman MR, Fey PD, Bayer AS. 2010. Cell wall thickening is not a universal accompaniment of the daptomycin nonsusceptibility phenotype in Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for multiple resistance mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3079–3085. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00122-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis JS, Sud A, O'Sullivan MVN, Robinson JO, Ferguson PE, Foo H, van Hal SJ, Ralph AP, Howden BP, Binks PM, Kirby A, Tong SYC, Combination Antibiotics for MEthicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CAMERA) study group, Tong S, Davis J, Binks P, Majumdar S, Ralph A, Baird R, Gordon C, Jeremiah C, Leung G, Brischetto A, Crowe A, Dakh F, Whykes K, Kirkwood M, Sud A, Menon M, Somerville L, Subedi S, Owen S, O'Sullivan M, Liu E, Zhou F, Robinson O, Coombs G, Ferguson P, Ralph A, Liu E, Pollet S, Van Hal S, Foo H, Van Hal S, Davis R. 2016. Combination of vancomycin and beta-lactam therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a pilot multicenter randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 62:173–180. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chambers HF, Basuino L, Hamilton SM, Choo EJ, Moise P. 2016. Daptomycin-beta-lactam combinations in a rabbit model of daptomycin-nonsusceptible methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:3976–3979. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00589-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jorgensen SCJ, Zasowski EJ, Trinh TD, Lagnf AM, Bhatia S, Sabagha N, Abdul-Mutakabbir JC, Alosaimy S, Mynatt RP, Davis SL, Rybak MJ. 2020. Daptomycin plus beta-lactam combination therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: a retrospective, comparative cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 71:1–10. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duss FR, Garcia de la Maria C, Croxatto A, Giulieri S, Lamoth F, Manuel O, Miro JM. 2019. Successful treatment with daptomycin and ceftaroline of MDR Staphylococcus aureus native valve endocarditis: a case report. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:2626–2630. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berti AD, Theisen E, Sauer JD, Nonejuie P, Olson J, Pogliano J, Sakoulas G, Nizet V, Proctor RA, Rose WE. 2016. Penicillin binding protein 1 is important in the compensatory response of Staphylococcus aureus to daptomycin-induced membrane damage and is a potential target for beta-lactam-daptomycin synergy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:451–458. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02071-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werth BJ, Sakoulas G, Rose WE, Pogliano J, Tewhey R, Rybak MJ. 2013. Ceftaroline increases membrane binding and enhances the activity of daptomycin against daptomycin-nonsusceptible vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus in a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:66–73. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01586-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, El Khoury G, Erba PA, Iung B, Miro JM, Mulder BJ, Plonska-Gosciniak E, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, Snygg-Martin U, Thuny F, Tornos Mas P, Vilacosta I, Zamorano JL, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 36:3075–3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Yeh AJ, Cheung GY, Villaruz AE, Tan VY, Joo HS, Chatterjee SS, Yu Y, Otto M. 2015. Basis of virulence in a Panton-Valentine leukocidin-negative community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain. J Infect Dis 211:472–480. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang R, Braughton KR, Kretschmer D, Bach TH, Queck SY, Li M, Kennedy AD, Dorward DW, Klebanoff SJ, Peschel A, DeLeo FR, Otto M. 2007. Identification of novel cytolytic peptides as key virulence determinants for community-associated MRSA. Nat Med 13:1510–1514. doi: 10.1038/nm1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2019. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 29th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison EM, Ba X, Coll F, Blane B, Restif O, Carvell H, Koser CU, Jamrozy D, Reuter S, Lovering A, Gleadall N, Bellis KL, Uhlemann AC, Lowy FD, Massey RC, Grilo IR, Sobral R, Larsen J, Rhod Larsen A, Vingsbo Lundberg C, Parkhill J, Paterson GK, Holden MTG, Peacock SJ, Holmes MA. 2019. Genomic identification of cryptic susceptibility to penicillins and beta-lactamase inhibitors in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Microbiol 4:1680–1691. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0471-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jenson RE, Baines SL, Howden BP, Mishra NN, Farah S, Lew C, Berti AD, Shukla SK, Bayer AS, Rose WE. 2020. Prolonged exposure to beta-lactam antibiotics reestablishes susceptibility of daptomycin-nonsusceptible staphylococcus aureus to daptomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e00890-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00890-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-de-la-Maria C, Gasch O, Garcia-Gonzalez J, Soy D, Shaw E, Ambrosioni J, Almela M, Pericas JM, Tellez A, Falces C, Hernandez-Meneses M, Sandoval E, Quintana E, Vidal B, Tolosana JM, Fuster D, Llopis J, Pujol M, Moreno A, Marco F, Miro JM. 2018. The combination of daptomycin and fosfomycin has synergistic, potent, and rapid bactericidal activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a rabbit model of experimental endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e02633-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02633-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berti AD, Baines SL, Howden BP, Sakoulas G, Nizet V, Proctor RA, Rose WE. 2015. Heterogeneity of genetic pathways toward daptomycin nonsusceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus determined by adjunctive antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2799–2806. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04990-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qu T, Feng Y, Jiang Y, Zhu P, Wei Z, Chen Y, Otto M, Yu Y. 2014. Whole genome analysis of a community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST59 isolate from a case of human sepsis and severe pneumonia in China. PLoS One 9:e89235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Novick R. 1967. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology 33:155–166. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peschel A, Gotz F. 1996. Analysis of the Staphylococcus epidermidis genes epiF, -E, and -G involved in epidermin immunity. J Bacteriol 178:531–536. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.531-536.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table S1. Download AAC.01295-21-s0001.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.01 MB (9.5KB, xlsx)

Supplemental Table S2. Download AAC.01295-21-s0002.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.01 MB (10.4KB, xlsx)

Supplemental Figure S1. Download AAC.01295-21-s0003.pdf, PDF file, 0.7 MB (708.1KB, pdf)