ABSTRACT

Failure of treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis with antimonial drugs and miltefosine is frequent. Use of oral combination therapy represents an attractive strategy to increase efficacy of treatment and reduce the risk of drug resistance. We evaluated the potency of posaconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and fluconazole and the potential synergy of those demonstrating the highest potency, in combination with miltefosine (HePC), against infection with Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis. Synergistic activity was determined by isobolograms and calculation of the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI), based on parasite quantification using an ex vivo model of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) infected with a luciferase-transfected, antimony and miltefosine sensitive line of L. panamensis. The drug combination and concentrations that displayed synergy were then evaluated for antileishmanial effect in 10 clinical strains of L. panamensis by reverse transcription-quantitative (qRT-PCR) of Leishmania 7SLRNA. High potency was substantiated for posaconazole and itraconazole against sensitive as well as HePC- and antimony-resistant lines of L. panamensis, whereas fluconazole and voriconazole displayed low potency. HePC combined with posaconazole (Poz) demonstrated evidence of synergy at free drug concentrations achieved in plasma during treatment (2 μM HePC plus 4 μM Poz). FICI, based on 70% and 90% reduction of infection, was 0.5 for the sensitive line. The combination of 2 μM HePC plus 4 μM Poz effected a significantly greater reduction of infection by clinical strains of L. panamensis than individual drugs. Orally administrable miltefosine/posaconazole combinations demonstrated synergistic antileishmanial capacity ex vivo against L. panamensis, supporting their potential as a novel therapeutic strategy to improve efficacy and effectiveness of treatment.

KEYWORDS: Leishmania, miltefosine, posaconazole, azoles, combined therapy

TEXT

Pentavalent antimonial drugs have been the first-line monotherapeutic treatment for dermal leishmaniasis in Central and South America for decades. Miltefosine (hexadecylphosphocholine, HePC), an oral drug originally developed for treatment of breast cancer, was approved in India in 2002 for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis and subsequently in various countries, including Colombia in 2005 for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in adults and children (1). Failure of monotherapeutic treatment for American cutaneous leishmaniasis has been estimated to be 20 to 30% with antimonial drugs (2–4), and 17 to 30% with miltefosine (4, 5). In addition, loss of susceptibility or intrinsic tolerance of Leishmania to these drugs has been demonstrated (6). Pediatric populations with cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) represent a particular therapeutic challenge for several reasons, including the 20- to 28-day duration of treatment, the parenteral administration of the most widely used antimonial drugs, and higher elimination rates of antimony and miltefosine in children (7, 8).

Some infectious diseases, such as HIV and tuberculosis, require that combinations of drugs be given for effective therapy and to prevent drug resistance (9). In line with these experiences, combination therapy for the treatment of CL has been advocated as a strategy to increase efficacy, reduce duration and cost of treatment, and diminish the risk of emergence of drug resistance. Additionally, combining orally administrable drugs with low toxicity could promote the adherence to and effectiveness of treatment, especially in the pediatric population.

Oral miltefosine is well tolerated and has shown efficacy for CL in children as well as adults in the Latin American region where Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis is prevalent (1, 4). Miltefosine efficacy for CL caused by L. (V.) braziliensis and L. (V.) guyanensis has also been demonstrated (10–12). However, data on the efficacy of miltefosine for L. (Leishmania) mexicana and related species are limited and uncertain (1). In vitro assays have shown variable potency of miltefosine against different species of Leishmania (13, 14) and evidence of lower potency against clinical strains of L. (V.) braziliensis than those of L. (V.) panamensis and L. (V.) guyanensis (6). Additionally, evidence of prompt selection for resistance has emerged under in vitro and in vivo conditions of miltefosine exposure (15–17).

Diverse oral antifungal azoles have been evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of CL, some of them showing moderate efficacy against Leishmania species from the New and Old World (18–21). The azoles are an important class of antifungal agents with a broad spectrum of activity against most yeasts and filamentous fungi and act in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway through inhibition of the cytochrome P450-dependent enzyme sterol 14a-demethylase (22). The triazole posaconazole, which is structurally similar to itraconazole (23, 24), has broad activity against both yeasts and molds and specifically retains activity against organisms that are resistant to other azoles, such as fluconazole (25). The ergosterol pathway has also been considered an important antileishmanial target based on the mechanism of action of amphotericin B against Leishmania (26). In vitro studies using promastigotes have provided evidence of the potency of fluconazole, itraconazole, and voriconazole for some New World Leishmania species (27–29). Similarly, in vitro evaluation has shown posanconazole to be potent against infection by L. amazonensis (30); however, little is known about its activity against other Leishmania species.

Considering the potential therapeutic gain in efficacy achievable by combining miltefosine and azoles in the treatment of CL, their oral administration, and low toxicity, we explored the feasibility of achieving increased potency against L. (V.) panamensis, the most prevalent causal agent of CL in Colombia (31, 32). Ex vivo assays using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), which include innate immune components of the response to infection and drug exposure, were performed to evaluate the potency of miltefosine (HePC), posaconazole (Poz), itraconazole (Itra), voriconazole (Vori), and fluconazole (Fluc). The evaluated drug concentrations were deliberately selected to correlate with concentrations of drug that are achievable in humans, particularly in pediatric populations (7, 8, 33–36). Consideration of safety and pharmacokinetics in the preclinical evaluation of these drug combinations provides the basis for future clinical assessment of the efficacy and tolerability of promising oral drug combinations.

RESULTS

Posaconazole and itraconazole have potent antileishmanial activity against intracellular amastigotes of L. (V.) panamensis.

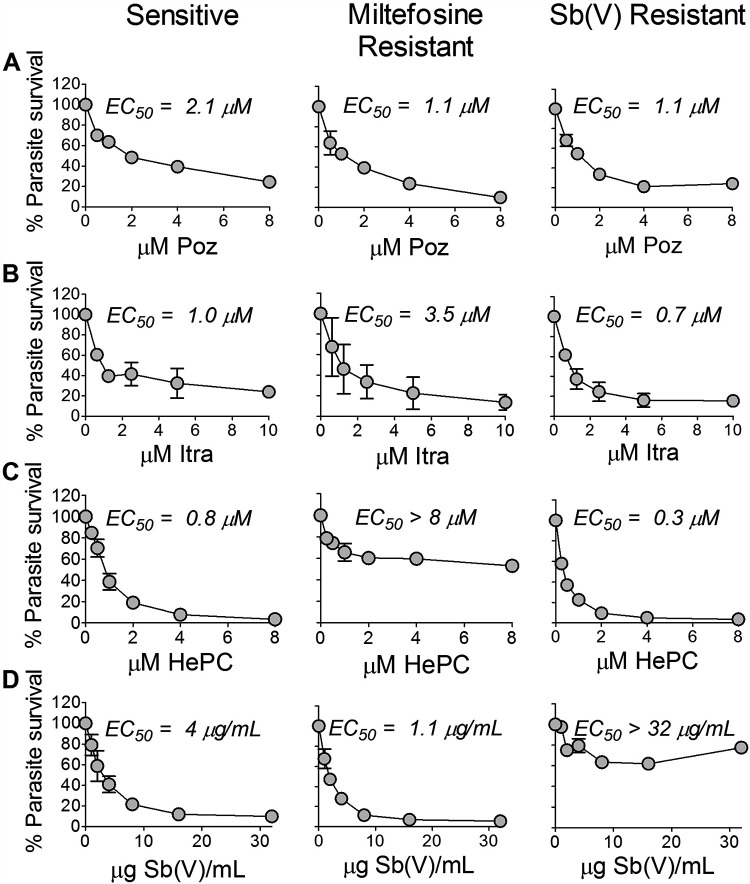

Antileishmanial activity of individual drugs against sensitive and HePC- or antimony SbV-resistant lines of L. (V.) panamensis lines in the ex vivo human PBMC model substantiated the potency of Poz and Itra (Fig. 1A and B). The 50% effective concentrations (EC50) of Poz and Itra for the HePC-resistant line were 1.1 and 3.5 μM, respectively, whereas the EC50 for HePC was >8 μM (10 times the EC50 of the sensitive line) (Fig. 1C). Similarly, the EC50 of Poz and Itra for the SbV-resistant line were 1.1 and 0.7 μM, respectively, in contrast to the EC50 of SbV, which was >32 μg/ml SbV (Fig. 1D), corresponding to the Cmax of Sb in plasma. The EC50 of Poz and Itra for the SbV- and HePC-sensitive line were 2.1 and 1.0 μM, respectively (Fig. 1A and B), concentrations that have been documented in the plasma of treated children as well as adults (34, 37, 38).

FIG 1.

Potency of posaconazole and itraconazole for intracellular amastigotes of L. (V.) panamensis. (A to D) Dose response of antileishmanial activity of Poz (A), Itra (B), HePC (C), and SbV (D) in PBMCs from healthy volunteers infected with drug-sensitive and HePC- or SbV-resistant lines. Data are based on 3 replicates for each condition per experiment and presented as the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) of two independent experiments for resistant lines and three experiments for the susceptible line.

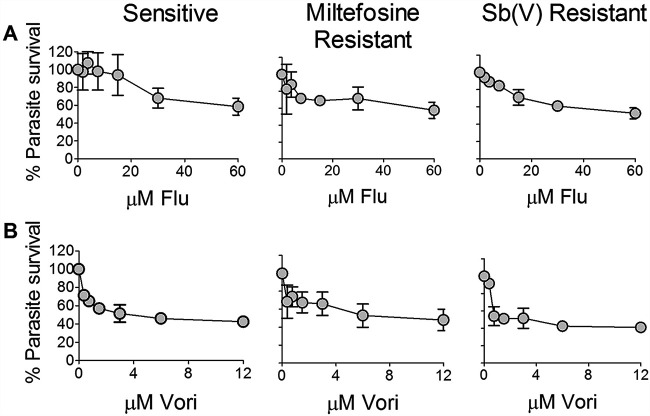

Other azole compounds evaluated, including fluconazole (Fluc) and voriconazole (Vori), which have been reported to be active against L. amazonensis (39) and L. donovani (29), had low antileishmanial activity against both sensitive and resistant laboratory lines of L. (V.) panamensis in the ex vivo infection of human PBMCs (Fig. 2A and B). At concentrations approximating the corresponding Cmax of free drug in plasma (Fluc, 39 μM; Vori, 2.9 μM) (36, 40), Fluc and Vori failed to achieve at least a 50% reduction of infection. Cytotoxicity evaluation of azoles under the experimental conditions of this study showed that Fluc, Vori, and Itra were not cytotoxic for PBMCs at concentrations of 100 μM; the ex vivo subcytotoxic concentration of Poz for PBMCs was 25 μM.

FIG 2.

Potency of fluconazole and voriconazole against intracellular amastigotes of L. (V.) panamensis. (A and B) Dose response of antileishmanial activity of Fluc (A) and Vori (B) in the ex vivo PBMC model infected with drug-sensitive and HePC- or SbV-resistant laboratory-derived lines. Data are based on three replicates for each condition per experiment and presented as the mean and SEM of two independent experiments.

Combination of miltefosine and posaconazole increased antileishmanial activity against the drug-sensitive laboratory line of L. (V.) panamensis.

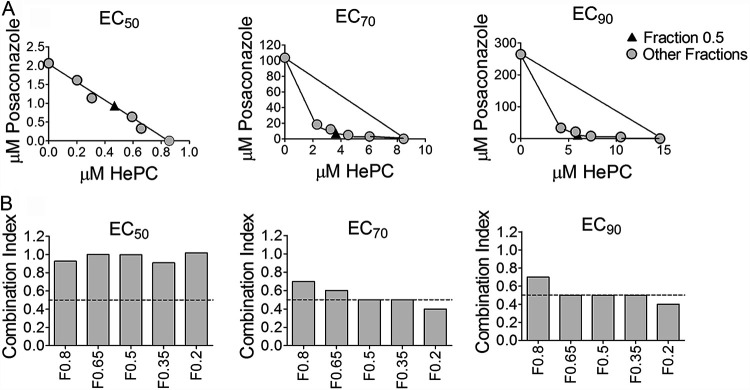

Based on the results of potency assays of individual drugs, Poz and Itra were selected for evaluation of interactions when combined with HePC. According to the combination index-isobologram method, HePC and Poz demonstrated synergy for fraction combination F0.5, F0.35, and F0.2 when parasite viability was reduced by 70% (EC70) and for F0.65, F0.5, F0.35, and F0.2 when parasite viability was reduced by 90% (EC90) for the drug-sensitive line (combination index, ≤0.5) (Fig. 3A and B). Based on these results, Fraction F0.5 for the HePC/Poz combination, corresponding to the relation 1:2 of HePC:Poz (Fig. 3A, filled triangle) was the most potent combination and therefore was selected for evaluation with clinical strains of L. (V.) panamensis. The concentrations 2 μM HePC:4 μM Poz, were selected because 2 μM miltefosine is well within achievable free drug (nonprotein bound) concentrations in plasma, and the corresponding pozaconazole concentration at the 1:2 ratio achieving synergy (4 μM) is at the lower end of achievable drug plasma concentration (33, 37). Isobologram analysis of the HePC/Itra combination showed a combination index of >0.85 for all fractions in the reduction of 50% (EC50), 70% (EC70), and 90% (EC90) of parasite viability, indicating the absence of synergy for any of the proportions and concentrations of HePC and Itra in combination.

FIG 3.

Isobolograms of miltefosine and posaconazole combinations. Representation of the EC50, EC70, and EC90 of the drugs combined (F0.2, F0.35, F0.5, F0.65, and F0.8) or alone (F0, Poz [y axis]; F1, HePC [x axis]) for infection with the L. (V.) panamensis drug-sensitive line. The black triangle in each panel corresponds to the fraction F0.5, selected as the optimal drug concentration for combination therapy (A). Combination index score for each fractional concentration (B). Synergy is defined by a fractional inhibitory concentration index ≤0.5. Each data point is based on a dose response curve of 6 concentrations of each drug or combination. Data are presented as the mean of two independent experiments.

The combination of miltefosine and posaconazole demonstrated significantly greater antileishmanial activity than either drug alone against intracellular amastigotes of clinical strains.

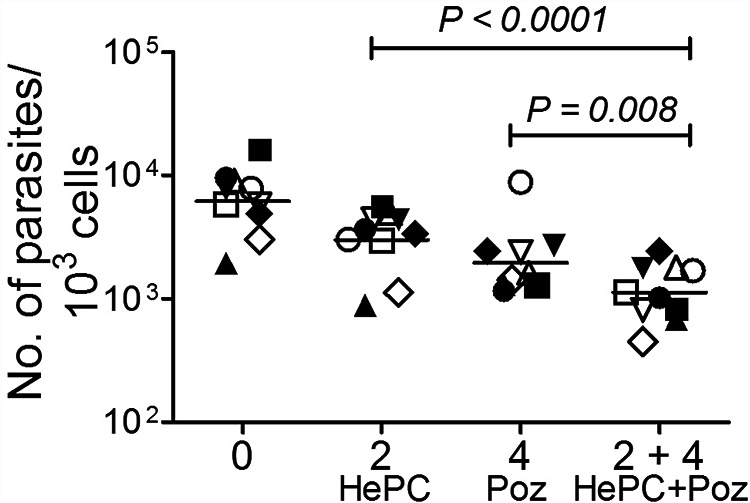

The concentrations and proportions of the drugs HePC (2 μM) and Poz (4 μM) selected in accordance with the synergistic effect based on the FICI index of HePC/Poz (≤0.5) for the drug-sensitive laboratory line, and on free drug Cmax in children (8, 37), showed significantly greater antileishmanial activity, measured as the reduction of parasite burden, against clinical strains of L. (V.) panamensis compared with the individual drugs (Fig. 4). The ratios of geometric mean loads were 0.37 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.25 to 0.56; P < 0.0001) for PBMCs infected with the clinical strains exposed to the combination of HePC/Poz compared to HePC alone and 0.57 (95% CI, 0.38 to 0.86; P = 0.008) compared to Poz alone. Clinical strains included both HePC-sensitive and -tolerant/resistant strains based on prior in vitro susceptibility in the U-937 human promonocytic cell line. There was no evidence of an effect of resistance phenotype on parasite burden (F = 0.005 on 1 and 34 degrees of freedom, P = 0.94).

FIG 4.

Antileishmanial activity of the selected miltefosine/posaconazole combination for intracellular amastigotes of clinical strains. Potency of the selected drug combination (2 μM HePC/4 μM Poz) and the same concentrations of each drug alone for clinical strains of L. (V.) panamensis using an ex vivo model of PBMCs. Ten clinical strains were evaluated, five sensitive (empty symbols) and five tolerant/resistant (filled symbols) to miltefosine based on previously conducted evaluations of susceptibility in U937 macrophages. Each data point corresponds with the mean parasite burden determined by quantitative PCR of Leishmania 7SLRNA in two replicate cultures of PBMCs from the same donor. Bars correspond with the geometric mean of the parasite burden of the 10 clinical strains of L. (V.) panamensis. Symbols represent individual clinical strains.

DISCUSSION

Safe, orally administrable therapeutic alternatives for CL are needed to improve the adherence to and effectiveness of treatment for all patients, but particularly for the pediatric population. We found that posaconazole and itraconazole have potent activity against sensitive and HePC- or SbV-resistant lines of L. (V.) panamensis in ex vivo human PBMCs, whereas fluconazole and voriconazole had low potency. Our study is the first investigation of the antileishmanial potential of Poz for a species of the Viannia subgenus. Furthermore, our results provide preclinical evidence of an alternative treatment for CL caused by L. (V.) panamensis based on combined therapy with the oral drugs miltefosine and posaconazole, both of which are in clinical use and known to be safe for administration in children as well as adults (37, 41, 42). Combination of these drugs at concentrations (2 μM and 4 μM, respectively) that can be achieved with dosing and therapeutic regimens used in children and adults (7, 8, 33–36) resulted in synergy at 70% and 90% of maximal antileishmanial activity against infection with a drug-sensitive line of L. (V.) panamensis. Considering that the goal of treatment is to maximally reduce parasite burden, this outcome supports the potential benefit of the combination.

Importantly, the combination was also significantly more potent than miltefosine (P < 0.0001) or Poz (P = 0.008) alone for clinical strains previously defined as tolerant/resistant to miltefosine in the U937 human macrophage model, validating the activity of the drug combination in parasites over the range of natural susceptibility to miltefosine, including apparent resistance. The intracellular achievability of the synergistic concentrations of HePC and Poz during treatment is supported by previously reported concentrations of these drugs in peripheral blood cells (8, 43).

Our initial evaluation of individual azole drugs using human PBMCs showed that Poz and Itra were the most potent, demonstrating a dose response effect in reducing the viability of intracellular amastigotes of SbV- and HePC-sensitive and -resistant lines of L. (V) panamensis. Poz and Itra are broad-spectrum drugs, orally administered and regularly used as prophylaxis or for treatment of fungal infections in immunosuppressed patients (37, 44); as such, there is significant clinical experience with these agents. Efficacy of Itra and Poz has been reported for patients with CL caused by L. infantum (45) and L. major (46). Additionally, in vitro assays have shown these azoles to have high potency for intracellular amastigotes of L. amazonensis (30) and L. tropica (47). The EC50 values of Poz and Itra reported for L. amazonensis using peritoneal macrophages from CF1 mice were 1.63 and 0.08 μM, respectively, similar to the EC50 values determined in this study for the laboratory lines of L. (V.) panamensis that are sensitive (Poz, 2.1 μM; Itra, 1 μM) or resistant to SbV (Poz, 1.1 μM; Itra, 0.7 μM) or HePC (Poz, 1.1 μM; Itra, 3.5 μM).

Based on our results, Poz appears to have the highest efficacy of the azoles evaluated against L. (V) panamensis, particularly when combined with HePC. The concentrations of Poz and HePC used in our studies correlate well with prior descriptions of plasma levels and intracellular concentrations achieved in treated patients (8, 43). We therefore propose that Poz has the potential to be repurposed for the treatment of leishmaniasis in combination with miltefosine. These findings compel evaluation of synergic activity of Poz and HePC for other species of this subgenus, particularly L. (V.) braziliensis, which is widely distributed in the Americas and presents variable susceptibility to HePC.

In addition to our experimental findings, other factors favor the use of Poz for CL. The mechanism of action of the various azoles suggests that Poz could have higher efficacy against this infection. Poz and Itra, similar to other antifungal azole compounds, are inhibitors of the enzyme 14α-demethylase (CYP51), which catalyzes the biosynthesis of ergosterol, a basic compound in the structure and function of the cell membrane of both fungi and trypanosomatids (48, 49). Poz has been shown to have potent antifungal activity against many pathogenic fungi; often its activity is greater than that of other azoles and amphotericin B (50). The greater potency of Poz against fungi that of other azoles is attributed to its chemical structure, which allows it to interact with an additional domain of the enzyme 14α-demethylase, inhibiting growth of Candida strains resistant to Fluc and Vori. Additionally, Poz is a poor substrate for efflux pumps in fungi and hence can remain active when other azoles have been expelled from host cells or microbial organisms (25).

Furthermore, several pharmacokinetic characteristics support Poz for treatment of CL. Penetration at the site of infection is a key requirement for the efficacy of all antimicrobial agents (51). According to their pharmacokinetics and lipophilic structure, Itra and Poz have a large volume of distribution, tend to penetrate preferentially in tissues with high lipid content, and often exhibit a tissue/plasma concentration ratio that exceeds 1 (51). Consequently, these azoles are more concentrated in certain tissues than in plasma. In relation to the skin, where parasites are localized, Fluc and Poz have been found to reach higher concentrations than in plasma (52, 53), whereas Itra tends to accumulate in sebaceous glands (54). Physiological factors such as inflammation, a common characteristic of leishmanial skin lesions, tend to increase tissue permeability and penetration of drugs into tissue as a result of the disruption of normal physiological barriers. Such an effect has been demonstrated for Itra and Fluc (55). In addition, intracellular accumulation of Itra has been shown in alveolar macrophages (56), and of Poz, in mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells, which can harbor Leishmania (43). These characteristics could contribute to the efficacy of azoles such as Poz in the treatment of CL.

Overall, the adverse events caused by azoles are classified as mild or moderate. Common adverse effects of Poz are gastrointestinal complaints such as nausea and vomiting, and for Itra, the same gastrointestinal complaints plus fever and exanthem (57). These are similar in type and severity to those observed with HePC in the treatment of CL. Notably, oral administration of Poz capsules provides more stable pharmacokinetics (PK) than administration as a suspension, during which PK has been shown to be affected by food intake (58, 59). Since the azoles and miltefosine are both known to cause liver toxicity, periodic monitoring of liver function by hepatic enzyme testing may be required if these drugs are combined in adult patients. However, posaconazole is typically considered less hepatotoxic by clinicians than other azoles such as itraconazole or voriconazole (60), and pediatric populations tend to have fewer hepatic side effects than adults (61), so liver function monitoring may be less necessary in younger patients taking Poz and HePC specifically. Whether the combination of Poz and HePC would result in increased frequency or severity of adverse events is not known; however, it is also plausible that lower exposure to each drug in combined regimens in terms of dose and duration of treatment could instead reduce adverse effects.

In conclusion, the results obtained in this study show that the combination of miltefosine and the broad-spectrum azole posaconazole is a promising candidate for more effective treatment of CL, particularly involving infection by L. (V.) panamensis. This species is overall clinically responsive to miltefosine and is the most prevalent species among diagnosed patients in Colombia (31, 62). Distinct mechanisms of action of azoles and miltefosine may contribute to the synergistic increase in the antileishmanial potency of their combination as well as reduce the risk of emergence of Leishmania (Viannia) populations that are tolerant or resistant to miltefosine. The clinical experience and knowledge of the pharmacology of Poz facilitate its repurposing for CL, as Poz is one of the most studied azoles for the treatment of mycosis in children and adults due to its potency and broad-spectrum activity (37, 57). Our results provide proof of concept for the therapeutic potential of the combination of HePC and Poz and encourage its clinical evaluation in patients infected with L. (V.) panamensis. Although the clinical benefit of the combination cannot be predicted, the unmet need for safe, effective, achievable treatment of patients within the rural context of CL, together with the accumulated knowledge and experience with these drugs, support clinical evaluation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental strategy.

We evaluated the potency of the combination of miltefosine (HePC) and different azole compounds to identify the drug combinations with the highest antileishmanial activity at achievable plasma concentrations. Based on published evidence of antileishmanial activity and therapeutic potential, Fluc, Vori, Itra, and Poz were selected for evaluation. Criteria for the selection of the azoles investigated were considered in the following order: oral administration, established safety in adults and children, concentration in skin and pharmacokinetics, potency in vitro, clinical efficacy/case reports for different Leishmania species.

HePC- and antimony (SbV)-sensitive and -resistant laboratory lines of L. (V.) panamensis transfected with luciferase (luc) (15, 63–65) (described in “Leishmania Strains and Lines”) were initially employed to evaluate parameters of potency of individual drugs, and then the most promising combination with HePC was determined using the drug-sensitive luc-transfected line. Accordingly, Poz and Itra were selected for analyses in combination with HePC. The drug concentrations in the combinations that displayed synergy were then evaluated for antileishmanial activity against 10 clinical strains of L. (V.) panamensis with disparate susceptibilities to HePC (5 sensitive and 5 tolerant/resistant) based on prior published results (6) of conventional in vitro evaluation of susceptibility in the U937 human promonocytic cell line (ATCC CRL-1593.2TM) (Table 1). Taking into consideration the importance of the immune/inflammatory response in the pathogenesis and resolution of leishmaniasis during natural infections, the antileishmanial assay of potency of the individual and combined drugs was conducted using human PBMC cultures, which encompass the participation of lymphocytes and host macrophages in parasite killing (64).

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility of L. (V.) panamensis clinical strains to HePC in the conventional model of U937 macrophages

| Strain code | % Parasite survival at 16 μM HePC |

|---|---|

| Resistant strains | |

| MHOM/COL/2009/5589 | 97 |

| MHOM/COL/2003/3784 | 77 |

| MHOM/COL/2007/5264 | 81 |

| MHOM/COL/2007/5261 | 94 |

| MHOM/COL/2003/3768 | 92 |

| Sensitive strains | |

| MHOM/COL/2009/5675 | 5 |

| MHOM/COL/2008/5498 | 7 |

| MHOM/COL/2004/6991 | 6 |

| MHOM/COL/2005/8190 | 5 |

| MHOM/COL/2004/6890 | 4 |

Study population and ethics statement.

Seven healthy male and female volunteers, between the ages of 18 and 60 years, without clinical history of leishmaniasis, participated in the study as donors of PBMCs. Volunteers were residents of the municipality of Cali, Colombia, and were enrolled within the Centro Internacional de Entrenamiento e Investigaciones Médicas (CIDEIM) research facilities in Cali. A blood sample of 100 mL was collected from each volunteer to obtain PBMCs for potency assays.

Ethics statement.

The study was approved and monitored by the CIDEIM Institutional Review Board for research involving human subjects in accordance with national and international guidelines for good clinical practice. Voluntary, informed, signed consent was provided by each participant.

PBMC isolation.

PBMCs were isolated by centrifugation over Histopaque 1077 solution (Sigma-Aldrich) according to product instructions. The cells were cryopreserved in 90% fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) by gradual cooling at approximately 1°C/minute using a freezing container (Thermo Scientific, USA) and then stored in liquid nitrogen until the time of experimental evaluation. Prior to use, the cells were rapidly thawed at 37°C, and PBMCs with ≥90% viability were used for the experiments (66).

Antileishmanial drugs.

Stock solutions of HePC, Fluc, Vori, Itra, and Poz (Cayman Chemical Co.) were prepared by dissolution in sterile dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Fisher Chemical) and stored at −20°C until use. Working solutions of the drugs were prepared in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) on the day of use. Maximal final concentration of DMSO in the PBMC culture was 0.2%.

Leishmania strains and lines.

The potency of drugs was evaluated in intracellular amastigotes of laboratory-adapted lines of L. (V.) panamensis transfected with the luciferase reporter gene as previously described (63). These lines included MHOM/COL/2003/3594/LUC001, which is sensitive to both SbV and HePC (64), and the drug-resistant lines MHOM/COL/1986/1166-1000.1, resistant to SbV (65, 67), and MHOM/COL/1986/1166-LUC056, resistant to HePC (15). The miltefosine- and antimony-resistant lines were propagated and maintained in the presence of 60 μmol HePC/L and 150 μg SbV/mL, respectively, and 80 μg/ml of Geneticin throughout propagation in culture.

Drug combinations were evaluated in 10 clinical strains of L. (V.) panamensis isolated from the same number of patients with CL. Clinical strains were selected according to susceptibility profile to a previously defined discriminatory concentration of HePC in differentiated macrophages of the promonocytic cell line U937, as previously described (16). Strains were classified as sensitive (n = 5) and tolerant/resistant (n = 5) based on the reduction of parasite burden when infected U-937 human macrophages were exposed to 16 μM HePC. The mean parasite survival for sensitive strains was 5% (range, 4 to 7%), and for tolerant/resistant strains, mean survival was 88% (range, 77 to 97%) compared with the corresponding control without drug (Table 1).

Drug cytotoxicity assays in PBMCs.

To control for potential confounding effects of drug cytoxicity for host PBMCs, cell viability was evaluated based on acid phosphatase activity (68) after 72 h of exposure to HePC, Fluc, Vori, Itra, and Poz at the concentrations employed in the potency assays for individual drugs and drug combinations. The subcytotoxic concentration was defined as the drug concentration resulting in less than 10% loss in cell viability comparing drug-exposed versus unexposed control cell cultures.

Potency assays using intracellular amastigotes.

Antileishmanial potency assays were conducted using an ex vivo human PBMC model as previously described (64). For all experiments, PBMCs were cultured at a final concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml. Infection with sensitive and resistant lines or clinical strains of L. (V.) panamensis was achieved by adding opsonized (human AB+ serum) stationary-phase promastigotes (day 6 of culture) in complete medium at a 10:1 parasite to monocyte ratio followed by incubation for 24 h at 34°C and 5% CO2. Afterward, individual drugs were added over a range of concentrations based on the Cmax for each drug in children (Poz, ≈1 to 4 μM; Itra, ≈0.8 to 4 μM; HePC, ≈2 to 3,6 μM; SbV, ≈32 μg/mL; Fluc, ≈17 to 38 μM; Vori, ≈1 to 2 μM) (7, 8, 33–36). Concentrations evaluated for each drug were the following: Poz, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 μM; Itra, 0.6, 1.2, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 μM; HePC, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 μM; SbV, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 μg/mL; Fluc, 1.8, 3.7, 7.5, 15, 30, and 60 μM; and Vori, 0.3, 0.7, 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 μM. Infected PBMCs were exposed to drugs for 72 h at 34°C and 5% CO2. Infection was quantified as luciferase activity using luminometry (Chameleon V multilabel microplate reader; Hidex, Finland) as previously described (63).

Evaluation of intracellular survival of clinical strains by real-time PCR.

The viability of clinical strains was evaluated by amplifying transcripts of the 7SLRNA gene of L. (V.) panamensis as previously described (69). Infected PBMCs (10 × 106 in total) cultured in six-well plates were collected in TRIzol for subsequent RNA extraction using the phenol-chloroform method. High-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kits (Applied Biosystems) were used for cDNA synthesis. The qRT-PCR was carried out with SYBR green qRT-PCR master mix (Life Technologies) using the TRY7SL forward primers (5′-TGC TCT GTA ACC TTC GGG GGC T-3′) and TRY7SL reverse (5′-GGC TGC TCC GTY NCC GGC CTG ACC C-3′), which amplifies a 179-bp transcript of 7SLRNA of Leishmania. Two technical replicates were performed for each sample, and measurement was carried out in real time using Bio-Rad CFX96 equipment. The specificity of qRT-PCR products was determined by melting curve analysis.

Drug combination studies.

The activity of drug combinations was evaluated in human PBMCs as described above. Drug interactions were defined using isobolograms and calculation of the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI). Dose response of the combined drugs in different proportions (F0.2, F0.35, F0.5, F0.65, and F0.8) or individual drugs (F0, azole; F1, HePC) were evaluated according to a previously described methodology (70). A combination was classified as synergistic if the FICI was ≤0.5, no interaction if the FICI was >0.5 to 4, and antagonistic if the FICI was >4. To better understand the magnitude of the interaction, the combination index was calculated for each ratio of the drug combination tested at the 50%, 70%, and 90% effective concentrations (EC50, EC70, and EC90). The drug combination and corresponding concentration and proportion with the highest antileishmanial activity was selected based on the FICI and evaluated in clinical strains.

Statistical analysis.

The EC50, EC70, and EC90 values were determined using the PROBIT procedure of the SPSS program (version 20). The combination index was determined as described previously (70). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to estimate and compare antileishmanial effects of individual drugs and their combination on clinical strains. More specifically, ANOVA was done on the log-transformed parasite burden, and the coefficients were back-transformed to be expressed in ratios of geometric means. For analysis of resistance status, the ANOVA included this and the drugs (miltefosine, posaconazole, neither or both). The final analysis included drugs and strain, in order to match to the latter. Both strain and resistance status cannot be included in the same analysis because the former determines the latter (i.e., they are aliased or perfectly colinear). Analyses were performed with Prism 6 (GraphPad, Inc., San Diego, CA) and R 4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) software. More specifically, ANOVA was done using the “aov” function in R. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our colleagues in the Clinical Research Unit, Miguel Dario Prieto and Jimena Jojoa for their assistance in the enrollment of volunteers, Maryori Vidarte and María Claudia Barrera for technical assistance in the culture and characterization of Leishmania strains used in this study, and Neal Alexander and Yenifer Orobio for their guidance in the statistical analyses. We gratefully acknowledge the support of Tawanda Gumbo of Baylor Institute of Immunology Research, Dallas, TX, during the development of the proposal for this investigation. Preliminary results of this work were previously presented in the international symposium “Omic Technologies for Infectious Disease Research” held in Cali, Colombia, in September 2017.

This research was financed by the Colombian National Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, COLCIENCIAS, contract number 666-2014, code 2229-657-41039, and supported in part by the Global Infectious Research Training Program of the Fogarty International Center of the U.S. National Institutes of Health under award number SD43TW006589 and NIH/NIAID Tropical Medicine Research Centers (TMRC) grant U19AI129910. D.M.W. was supported by NIAID K08 Award AI103036, a Children’s Clinical Research Advisory Committee Early Investigator Award, and the Welch Foundation (I-2086).

We declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Olga Lucía Fernández, Email: ofernandez@cideim.org.co.

Nancy Gore Saravia, Email: saravian@cideim.org.co.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soto J, Arana BA, Toledo J, Rizzo N, Vega JC, Diaz A, Luz M, Gutierrez P, Arboleda M, Berman JD, Junge K, Engel J, Sindermann H. 2004. Miltefosine for new world cutaneous leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis 38:1266–1272. doi: 10.1086/383321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llanos-Cuentas A, Tulliano G, Araujo-Castillo R, Miranda-Verastegui C, Santamaria-Castrellon G, Ramirez L, Lazo M, De Doncker S, Boelaert M, Robays J, Dujardin J-C, Arevalo J, Chappuis F. 2008. Clinical and parasite species risk factors for pentavalent antimonial treatment failure in cutaneous leishmaniasis in Peru. Clin Infect Dis 46:223–231. doi: 10.1086/524042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soto J, Toledo J, Vega J, Berman J. 2005. Short report: efficacy of pentavalent antimony for treatment of Colombian cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 72:421–422. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubiano LC, Miranda MC, Muvdi Arenas S, Montero LM, Rodríguez-Barraquer I, Garcerant D, Prager M, Osorio L, Rojas MX, Pérez M, Nicholls RS, Gore Saravia N. 2012. Noninferiority of miltefosine versus meglumine antimoniate for cutaneous leishmaniasis in children. J Infect Dis 205:684–692. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velez I, López L, Sánchez X, Mestra L, Rojas C, Rodríguez E. 2010. Efficacy of miltefosine for the treatment of American cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 83:351–356. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez OL, Diaz-Toro Y, Ovalle C, Valderrama L, Muvdi S, Rodríguez I, Gomez MA, Saravia SG. 2014. Miltefosine and antimonial drug susceptibility of Leishmania Viannia species and populations in regions of high transmission in Colombia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8:e2871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz A, Rainey PM, Herwaldt BL, Stagni G, Palacios R, Trujillo R, Saravia NG. 2007. Pharmacokinetics of antimony in children treated for leishmaniasis with meglumine antimoniate. J Infect Dis 195:602–608. doi: 10.1086/510860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro M.dM, Gomez MA, Kip AE, Cossio A, Ortiz E, Navas A, Dorlo TPC, Saravia NG. 2017. Pharmacokinetics of Miltefosine in Children and Adults with Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02198-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02198-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Worthington RJ, Melander C. 2013. Combination approaches to combat multidrug-resistant bacteria. Trends Biotechnol 31:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soto J, Rea J, Balderrama M, Toledo J, Soto P, Valda L, Berman JD. 2008. Efficacy of miltefosine for Bolivian cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 78:210–211. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2008.78.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soto J, Toledo J, Gutierrez P, Nicholls RS, Padilla J, Engel J, Fischer C, Voss A, Berman J. 2001. Treatment of American cutaneous leishmaniasis with miltefosine, an oral agent. Clin Infect Dis 33:E57–E61. doi: 10.1086/322689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chrusciak-Talhari A, Dietze R, Chrusciak Talhari C, da Silva RM, Gadelha Yamashita EP, de Oliveira Penna G, Lima Machado PR, Talhari S. 2011. Randomized controlled clinical trial to access efficacy and safety of miltefosine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania (Viannia) guyanensis in Manaus, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 84:255–260. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Escobar P, Matu S, Marques C, Croft SL. 2002. Sensitivities of Leishmania species to hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine), ET-18-OCH(3) (edelfosine) and amphotericin B. Acta Trop 81:151–157. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(01)00197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yardley V, Croft SL, De Doncker S, Dujardin J-C, Koirala S, Rijal S, Miranda C, Llanos-Cuentas A, Chappuis F. 2005. The sensitivity of clinical isolates of Leishmania from Peru and Nepal to miltefosine. Am J Trop Med Hyg 73:272–275. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2005.73.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obonaga R, Fernández OL, Valderrama L, Rubiano LC, Castro M.dM, Barrera MC, Gomez MA, Gore Saravia N. 2014. Treatment failure and miltefosine susceptibility in dermal leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania subgenus Viannia species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:144–152. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01023-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez O, Diaz-Toro Y, Valderrama L, Ovalle C, Valderrama M, Castillo H, Perez M, Saravia NG. 2012. Novel approach to in vitro drug susceptibility assessment of clinical strains of Leishmania spp. J Clin Microbiol 50:2207–2211. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00216-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez-Victoria FJ, Sánchez-Cañete MP, Seifert K, Croft SL, Sundar S, Castanys S, Gamarro F. 2006. Mechanisms of experimental resistance of Leishmania to miltefosine: implications for clinical use. Anticancer Chemotherapy 9:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emad M, Hayati F, Fallahzadeh MK, Namazi MR. 2011. Superior efficacy of oral fluconazole 400 mg daily versus oral fluconazole 200 mg daily in the treatment of cutaneous leishmania major infection: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 64:606–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dogra J, and, Saxena VN. 1996. Itraconazole and leishmaniasis: a randomised double-blind trial in cutaneous disease. Int J Parasitol 26:1413–1415. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(96)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saenz RE, Paz H, and, Berman JD. 1990. Efficacy of ketoconazole against Leishmania braziliensis panamensis cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Med 89:147–155. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90292-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galvao EL, Rabello A, and, Cota GF. 2017. Efficacy of azole therapy for tegumentary leishmaniasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 12:e0186117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maertens JA. 2004. History of the development of azole derivatives. Clin Microbiol Infect 10(Suppl 1):1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herbrecht R. 2004. Posaconazole: a potent, extended-spectrum triazole anti-fungal for the treatment of serious fungal infections. Int J Clin Pract 58:612–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2004.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres HA, Hachem RY, Chemaly RF, Kontoyiannis DP, Raad II. 2005. Posaconazole: a broad-spectrum triazole antifungal. Lancet Infect Dis 5:775–785. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hof H. 2006. A new, broad-spectrum azole antifungal: posaconazole—mechanisms of action and resistance, spectrum of activity. Mycoses 49(Suppl 1):2–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCall L-I, El Aroussi A, Choi JY, Vieira DF, De Muylder G, Johnston JB, Chen S, Kellar D, Siqueira-Neto JL, Roush WR, Podust LM, McKerrow JH. 2015. Targeting ergosterol biosynthesis in Leishmania donovani: essentiality of sterol 14 alpha-demethylase. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0003588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beach DH, Goad LJ, and, Holz GG. 1988. Effects of antimycotic azoles on growth and sterol biosynthesis of Leishmania promastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol 31:149–162. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ginouvès M, Simon S, Nacher M, Demar M, Carme B, Couppié P, Prévot G. 2017. In vitro sensitivity of cutaneous Leishmania promastigote isolates circulating in French Guiana to a set of drugs. Am J Trop Med Hyg 96:1143–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kulkarni MM, Reddy N, Gude T, McGwire BS. 2013. Voriconazole suppresses the growth of Leishmania species in vitro. Parasitol Res 112:2095–2099. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Macedo-Silva ST, Urbina JA, de Souza W, Rodrigues JCF. 2013. In vitro activity of the antifungal azoles itraconazole and posaconazole against Leishmania amazonensis. PLoS One 8:e83247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saravia NG, Weigle K, Navas C, Segura I, Valderrama L, Valencia AZ, Escorcia B, McMahon-Pratt D. 2002. Heterogeneity, geographic distribution, and pathogenicity of serodemes of Leishmania viannia in Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 66:738–744. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ovalle CE, Porras L, Rey M, Ríos M, Camargo YC. 2012. Geographic distribution of Leishmania species isolated from patients at the National Institute of Dermatology Federico Lleras Acosta E.S.E., 1995–2005. Biomedica 26:145–151. (In Spanish.) doi: 10.7705/biomedica.v26i1.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groll AH, Abdel-Azim H, Lehrnbecher T, Steinbach WJ, Paschke A, Mangin E, Winchell GA, Waskin H, Bruno CJ. 2020. Pharmacokinetics and safety of posaconazole intravenous solution and powder for oral suspension in children with neutropenia: an open-label, sequential dose-escalation trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 56:106084. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmitt C, Perel Y, Harousseau JL, Lemerle S, Chwetzoff E, Le Moing JP, Levron JC. 2001. Pharmacokinetics of itraconazole oral solution in neutropenic children during long-term prophylaxis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:1561–1564. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1561-1564.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nahata MC, Tallian KB, and, Force RW. 1999. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in young infants. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 24:155–157. doi: 10.1007/BF03190361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neely M, Rushing T, Kovacs A, Jelliffe R, Hoffman J. 2010. Voriconazole pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in children. Clin Infect Dis 50:27–36. doi: 10.1086/648679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doring M, Müller C, Johann P-D, Erbacher A, Kimmig A, Schwarze C-P, Lang P, Handgretinger I, Müller I. 2012. Analysis of posaconazole as oral antifungal prophylaxis in pediatric patients under 12 years of age following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. BMC Infect Dis 12:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Iersel M, Rossenu S, de Greef R, Waskin H. 2018. A population pharmacokinetic model for a solid oral tablet formulation of posaconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62: e02465-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02465-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliveira MB, Calixto G, Graminha M, Cerecetto H, González M, Chorilli M. 2015. Development, characterization, and in vitro biological performance of fluconazole-loaded microemulsions for the topical treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Biomed Res Int 2015:396894. doi: 10.1155/2015/396894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nahata MC, and, Brady MT. 1995. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole after oral administration in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 48:291–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00198314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiederhold NP. 2016. Pharmacokinetics and safety of posaconazole delayed-release tablets for invasive fungal infections. Clin Pharmacol 8:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mbui J, Olobo J, Omollo R, Solomos A, Kip AE, Kirigi G, Sagaki P, Kimutai R, Were L, Omollo T, Egondi TW, Wasunna M, Alvar J, Dorlo TPC, Alves F. 2019. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of an allometric miltefosine regimen for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in eastern African children: an open-label, phase II clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis 68:1530–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farowski F, Cornely OA, Vehreschild JrgJ, Hartmann P, Bauer T, Steinbach A, RüPing MJGT, Müller C. 2010. Intracellular concentrations of posaconazole in different compartments of peripheral blood. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:2928–2931. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01407-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Groll AH. 2002. Itraconazole-perspectives for the management of invasive aspergillosis. Mycoses 45(Suppl 3):48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2002.tb04770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paniz Mondolfi AE, Stavropoulos C, Gelanew T, Loucas E, Perez Alvarez AM, Benaim G, Polsky B, Schoenian G, Sordillo EM. 2011. Successful treatment of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum with posaconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1774–1776. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01498-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White JML, Salisbury JR, Jones J, Higgins EM, Vega-Lopez F. 2006. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: three children with Leishmania major successfully treated with itraconazole. Pediatr Dermatol 23:78–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khazaeli P, Sharifi I, Talebian E, Heravi G, Moazeni E, Mostafavi M. 2014. Anti-leishmanial effect of itraconazole niosome on in vitro susceptibility of Leishmania tropica. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 38:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Souza W, and, Rodrigues JC. 2009. Sterol biosynthesis pathway as target for anti-trypanosomatid drugs. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2009:642502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kazan K, and, Gardiner DM. 2017. Targeting pathogen sterols: defence and counterdefence? PLoS Pathog 13:e1006297. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabatelli F, Patel R, Mann PA, Mendrick CA, Norris CC, Hare R, Loebenberg D, Black TA, McNicholas PM. 2006. In vitro activities of posaconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B against a large collection of clinically important molds and yeasts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2009–2015. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00163-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Felton T, Troke PF, and, Hope WW. 2014. Tissue penetration of antifungal agents. Clin Microbiol Rev 27:68–88. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00046-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krishna G, Beresford E, Ma L, Vickery D, Martinho M, Yu X, Komjathy S, Tavakkol A. 2010. Skin concentrations and pharmacokinetics of posaconazole after oral administration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:1807–1810. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01616-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brammer KW, Farrow PR, and, Faulkner JK. 1990. Pharmacokinetics and tissue penetration of fluconazole in humans. Rev Infect Dis 12 Suppl 3:S318–26. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_3.s318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cauwenbergh G, Degreef H, Heykants J, Woestenborghs R, Van Rooy P, Haeverans K. 1988. Pharmacokinetic profile of orally administered itraconazole in human skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 18:263–268. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(88)70037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Savani DV, Perfect JR, Cobo LM, Durack DT. 1987. Penetration of new azole compounds into the eye and efficacy in experimental Candida endophthalmitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 31:6–10. doi: 10.1128/AAC.31.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perfect JR, Savani DV, Durack DT. 1993. Uptake of itraconazole by alveolar macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 37:903–904. doi: 10.1128/AAC.37.4.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doring M, Blume O, Haufe S, Hartmann U, Kimmig A, Schwarze C-P, Lang P, Handgretinger R, Müller I. 2014. Comparison of itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole as oral antifungal prophylaxis in pediatric patients following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 33:629–638. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1998-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wass EN, Hernandez EA, and, Sierra CM. 2020. Comparison of the efficacy of posaconazole delayed release tablets and suspension in pediatric hematology/oncology patients. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 25:47–52. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-25.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jung DS, Tverdek FP, and, Kontoyiannis DP. 2014. Switching from posaconazole suspension to tablets increases serum drug levels in leukemia patients without clinically relevant hepatotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:6993–6995. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04035-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mohr J, Johnson M, Cooper T, Lewis JS, Ostrosky-Zeichner L. 2008. Current options in antifungal pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy 28:614–645. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.5.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brady MT, Kimberlin DW, Long SS (ed). 2018. Red book: 2018–2021 report of the committee on infectious diseases, 31st ed. American Academy of Pediatrics, Itasca, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salgado-Almario J, Hernandez CA, Ovalle CE. 2019. Geographical distribution of Leishmania species in Colombia, 1985–2017. Biomedica 39:278–290. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.v39i3.4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Romero IC, Saravia NG, and, Walker J. 2005. Selective action of fluoroquinolones against intracellular amastigotes of Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis in vitro. J Parasitol 91:1474–1479. doi: 10.1645/GE-3489.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gonzalez-Fajardo L, Fernández OL, McMahon-Pratt D, Saravia NG. 2015. Ex vivo host and parasite response to antileishmanial drugs and immunomodulators. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0003820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goyeneche-Patino DA, Valderrama L, Walker J, Saravia NG. 2008. Antimony resistance and trypanothione in experimentally selected and clinical strains of Leishmania panamensis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:4503–4506. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01075-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sambor A, Garcia A, Berrong M, Pickeral J, Brown S, Rountree W, Sanchez A, Pollara J, Frahm N, Keinonen S, Kijak GH, Roederer M, Levine G, D'Souza MP, Jaimes M, Koup R, Denny T, Cox J, Ferrari G. 2014. Establishment and maintenance of a PBMC repository for functional cellular studies in support of clinical vaccine trials. J Immunol Methods 409:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Walker J, Gongora R, Vasquez J-J, Drummelsmith J, Burchmore R, Roy G, Ouellette M, Gomez MA, Saravia NG. 2012. Discovery of factors linked to antimony resistance in Leishmania panamensis through differential proteome analysis. Mol Biochem Parasitol 183:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang TT, Sinai P, and, Kain SR. 1996. An acid phosphatase assay for quantifying the growth of adherent and nonadherent cells. Anal Biochem 241:103–108. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Romero I, Téllez J, Suárez Y, Cardona M, Figueroa R, Zelazny A, Saravia NG. 2010. Viability and burden of Leishmania in extralesional sites during human dermal leishmaniasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4:103–108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Straetemans R, O’Brien T, Wouters L, Van Dun J, Janicot M, Bijnens L, Burzykowski T, Aerts M. 2005. Design and analysis of drug combination experiments. Biom J 47:299–308. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200410124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]