Abstract

Introduction

Although erectile dysfunction (ED) involves an interaction between physiological and psychological pathways, the psychosocial aspects of ED have received considerably less attention so far.

Aim

To review the available evidence on the psychosocial aspects of ED in order to develop a position statement and clinical practice recommendations on behalf of the European Society of Sexual Medicine (ESSM).

Method

A comprehensive, narrative review of the literature was performed.

Main outcome measures

Specific statements and recommendations according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence criteria were provided.

Results

A multidisciplinary treatment, in which medical treatment is combined with a psychological approach, is preferred over unimodal treatment. There is increasing evidence that psychological treatments of ED can improve medical treatments, the patient's adherence to treatment, and the quality of the sexual relationship. The main components of psychological treatment of ED involve cognitive and behavioral techniques aimed at reducing anxiety, challenging dysfunctional beliefs, increasing sexual stimulation, disrupting sexual avoidance, and increasing intimacy and communication skills in a relational context. When applicable and possible, it is strongly recommended to include the partner in the assessment and treatment of ED and to actively work on interpartner agreement and shared decision-making regarding possible treatment options. To ensure a better integration of the biopsychosocial model into clinical practice, developing concrete treatment protocols and training programs are desirable.

Conclusion

Because the psychosocial approach to ED has been underexposed so far, this position statement provides valuable information for clinicians treating ED. Psychological interventions on ED are based on existing theoretical models that are grounded in empirical evidence. However, the quality of available studies is low, which calls for further research. The sexual medicine field would benefit from pursuing more diversity, inclusivity, and integration when setting up treatments and evaluating their effect.

Dewitte M, Bettocchi C, Carvalho J, et al. A Psychosocial Approach to Erectile Dysfunction: Position Statements from the European Society of Sexual Medicine (ESSM). Sex Med 2021;9:100434.

Key Words: Erectile Dysfunction, Sexology, Psychotherapy, Biopsychosocial

INTRODUCTION

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is one of the most prevalent sexual disorders in men and has therefore attracted much research attention.1, 2, 3 Most studies, however, are uniformly directed towards exploring biological markers, which is partly due to the widespread and easy accessibility of medical treatments such as phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDEi5) since the late 90s, leaving the psychological and social underpinnings of ED underexposed. This is remarkable because erectile function involves a dynamic interplay between vascular, neurologic, hormonal as well as psychological and relational/social factors.4,5 Furthermore, a disruption of the sexual response causes considerable distress in men and their partners.6, 7, 8 Differentiating between organic vs nonorganic ED may be less relevant when considering that physical, psychological, and social factors are always involved and will interact to determine the behavioral expression of ED. Accordingly, the exclusive use of an organic model could expose the clinician to an underestimation of psycho-relational variables. This neglect may negatively bear on the patient's adhesion to the treatment. By now, there are several review papers and clinical guidelines available on ED,9, 10, 11, 12, 13 but the majority of these papers approach the assessment and treatment of ED from a purely medical perspective and pay only little attention to describing the psychosocial aspects of ED. Although increasingly more clinicians have started to integrate psychological assessment and advices in ED protocols, there are only few papers available that provide a comprehensive and exclusive overview of the psychological and relational/social aspects underlying ED.7,14 The aim of this paper, on behalf of the European Society of Sexual Medicine (ESSM), is to review the available evidence on the psychosocial variables for the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of ED, in order to complement existing medical grounded knowledge, and to provide a position statement and recommendations for clinical practice.

METHOD

A comprehensive literature search was conducted on the main scientific databases (Pubmed, Web of Science, Psych Info, Medline, and Cochrane) using the following words: erectile dysfunction, erectile disorder, erectile difficulties, erectile problem, paired with psychogenic OR psychological OR social OR interpersonal OR partner OR relationship OR intervention. Publications up to February 2020 were included. Only papers that explicitly focused on psychological and social/relational aspects of ED were considered. In addition, only papers targeting cismen with ED were included as the literature on ED has focused mainly on cismen and research with other identities (eg, transmen) is still very limited. The statements were internally discussed among a team of experts appointed by the ESSM. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The quality of the evidence was graded, and levels of evidence were provided according to the Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence criteria (https://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-basedmedicine-levels-evidence-march-2009).

ETIOLOGY OF ED

Statement#1: The etiology of ED is multifactorial and therefore a biopsychosocial approach is required. (Good Clinical Practice Statement).

Evidence

Psychological Factors

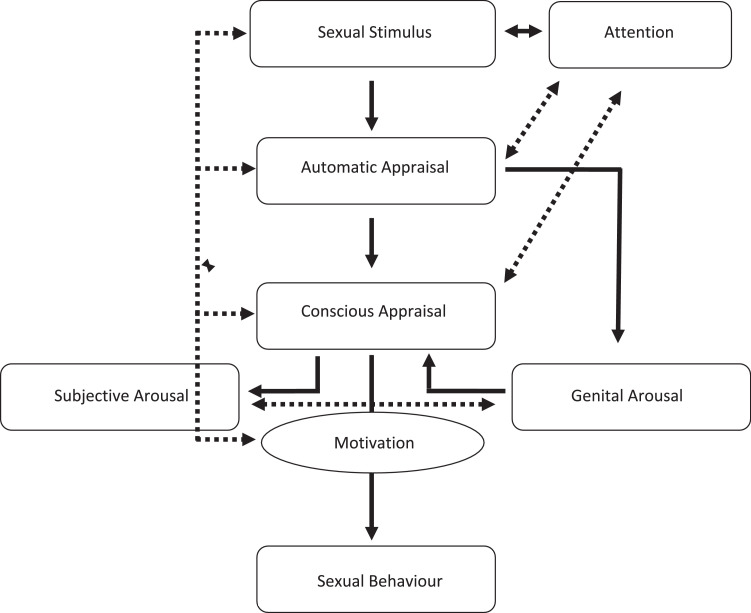

Most of the evidence on the psychosocial etiology of ED is based on theoretical models that are commonly accepted, but not sufficiently validated by high quality experimental studies. Figure 1 presents an overview of the cognitive-motivational processes involved in sexual response generation.16,17 A first important implication is that an adequate sexual stimulus is needed to activate the sexual arousal response.16 Accordingly, ED may result from a lack of sexual stimulation or a limited sexual repertoire that has lost its arousing properties throughout the years. Another important implication concerns the difference between subjective and genital arousal. Given that awareness of growing physiological signals (ie, genital swelling) is a key element in sexual responding, it is assumed that stronger feedback links between the cognitive and physical components of the sexual system will likely increase sexual arousability.16 There is evidence that men with ED show lower genital arousal (as indexed by lower average genital temperature and temperature change) in response to sexual stimuli, compared to men without ED.18 Furthermore, men with ED have been found to show lower agreement between their subjective and genital arousal, which implies that, particularly in men with ED, subjective arousal can be experienced without being physically aroused.18

Figure 1.

A sexual response model based on the models of Janssens et al, 2000.15

Cognitive factors might also play a role in here and disrupt the cascade of sexual arousal responding.19,20 Men who experience erectile difficulties enter a sexual situation with high negative affect and low positive affect, along with negative expectations about their sexual performance. This mindset induces an attentional shift towards cues that signal failure and a strong evaluative focus on their own bodily signals, which distracts them from erotic cues. They react with spectatoring, self-monitoring, performance demands, and failure anxiety, which are frequently associated with an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity, leading to genital arousal inhibition.15,18,19 Eventually, some men will avoid sexual activity, thereby maintaining or worsening the initial negative affect associated with sex.19,21 A recent meta-analysis including 2,118 patients receiving internet-based cognitive behavior therapy has shown that more severe anxiety symptoms represent a crucial factor for successful positive ED outcomes.22 In addition to cognitive distraction, negative automatic thoughts (eg, I am a failure, I need to perform, my erection is not firm enough) and macho-beliefs that involve unrealistic, unattainable expectations of male sexual performance (eg, penile erection is essential for a woman's sexual satisfaction, failing to get an erection may result in the woman leaving me) may predispose men to get trapped into a vicious circle of ED.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Other cognitive processes are attributions about the cause and level of control regarding their negative sexual experiences.29 Men with ED tend to attribute the erectile failure to their own incompetence (internal attribution) and experience a lower sense of control or self-efficacy.20,30,31

Furthermore, self-blame and negative affect are higher when men attribute their ED to psychological or relational causes as opposed to organic causes.20 There is also evidence showing that men with ED report lower levels of self-confidence, more negative self-schema's, and a negative body-image.21,32, 33, 34, 35 They are also found to display worrying, perseverative thinking, catastrophizing, and thought control strategies19 as well as higher levels of perfectionism, neuroticism, and somatization.36,37 According to the Dual Control Model, individuals vary in their propensity for excitation and inhibition, which may lead to problems with sexual function and behavior.38,39 Particularly a higher propensity for sexual inhibition due to threat of sexual performance failure, rather than lower levels of excitation, would constitute a risk factor for the development and maintenance of ED.39 Support for the clinical validity of the Dual Control Model is derived from a previous study including 146 men with ED and 446 age-matched controls.40 The authors showed that that subjects with ED who reported normal sleep-related erections or better erections during masturbation than during sexual intercourses, both suggestive of a psychogenic problem,41 showed higher sexual excitation, but not higher sexual inhibition.

Other important psychological factors to be considered are depression and anxiety. Excessive levels of anxiety may strengthen the focus on erectile failure and performance demand, which are core elements in the pathogenesis of ED.42 In particular, anxiety could be considered as the final common pathway by which social, psychological, and biological stressors disrupt sexual functioning.42,43 Accordingly, data performed in a large sample of patients seeking medical care for ED showed that free-floating anxiety has a relevant impact on maintaining the erection during intercourse which is another factor supporting a nonorganic origin of the problem.43

Regarding depression, several studies have suggested a reciprocal relationship with ED. The prevalence of ED is almost 5-fold higher in men with depression and, vice versa, men with ED often report higher rates of depression.44, 45, 46 Accordingly, data derived from a meta-analysis including 12 studies and more than 14,000 participants followed up to 10 years, showed that depression was associated with a 70% increased risk of ED, whereas ED was associated with a more than 3-fold increased risk of depression.45 The mechanisms underlying this association are probably both biologically and psychologically driven. Patients with depression have generally lower levels of energy and lack interest or motivation (ie, anhedonia).46 In addition, patients are characterized by negative thoughts and low self-confidence, resulting in performance anxiety and eventually ED. At the same time, the biological working hypothesis suggests that depression can be the consequence of hypothalamic pituitary adrenocortical (HPA) axis perturbation, leading to an excess catecholamine release and a serotonin production impairment, which in turn can cause poor cavernosal muscle relaxation and sexual avoidance.46 Moreover, most anti-depressants have negative effects on erectile and orgasmic function.47,48

Social/Relational Factors

The relational dynamics that contribute to or result from the sexual problem represent another crucial point in ED patient evaluation.14,49,50 Not only does ED and its treatment involve a shared stressor that is challenging for both partners, but it is also common that sexual changes in 1 partner go along with sexual changes in the other partner.14,51,52 Accordingly, evidence has shown that female partners of men with ED more frequently report sexual problems52 as well as reduced quality of their sex life due to lower levels of intimacy and foreplay.53,54

ED can also cause trust issues in partners who rely on their men's “spontaneous” erection as a sign of sexual attractiveness. As a result of the changes in a man's sexual behavior, partners may start to doubt themselves or suppose potential betrayal and infidelity.55 In some cases, the use of PDE5 inhibitors may generate false beliefs regarding the possibility to have an erection in all sexual occasions, beyond the partner's seductive capacity.49 Difficulties to openly talk about sex and communicate about likes and dislikes may further increase the negative sexual experiences.54,56, 57, 58, 59, 60 As the prevalence of ED increases with age, partners may also face their own sexual changes (whether or not driven by menopause or disease), which has an impact on sexual recovery.61 Evidence has shown that partners of men with nonorganic or psychological ED report more psychosexual issues than men with organic ED.62 In addition, it has been found that men with ED report lower levels of relationship satisfaction and more relationship conflict than men without ED and that intimacy is an important correlate of sexual satisfaction in men with ED.27,62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 Finally, in addition to relational and partner-related factors, it also important to consider the influence of media and societal expectations that create pressure on the male sexual performance, thereby fueling macho-beliefs, sexual myths, and unrealistic ideas about the perfect intercourse model.27,68

Remarks

The vast majority of research on the psychological etiology of ED is derived from cross-sectional studies, which implies that no conclusions can be made regarding cause or effect. Most likely, reciprocal relationships and feedback loops exist between ED and psychosocial mechanisms. For example, although ED has a clear impact on the partner and the relationship, it could be that pre-existing communication problems or relational dissatisfaction and conflict may exacerbate the manifestation of and coping with ED. In addition, it is important to recognize that most studies on the interpersonal dynamics of ED include heterosexual, monogamous samples,69 so the results are not simply generalizable to partners in other relationship types or LGBTQI+ individuals/couples. Hence, more experimentally controlled and prospective studies are needed to better understand how psychosocial factors are implicated in ED. Finally, it should be recognized that ED represent multifactorial disorders in which organic relation and psychological factors mutually interact among each other. Hence, although psychosocial and relational factors can maintain or worsen an organic problem, the presence of organic factors must be accurately ruled out in all patients complaining of ED.

DIAGNOSTIC ISSUES OF ED

Statement #2: The diagnostic process of ED should take into account diversity in terms of onset, context, age, and sexual orientation (Level 2, Grade C).

Statement #3: Questionnaires and structured interviews can support the diagnostic process but must not be considered a replacement of history taking. (Good Clinical Practice Statement).

Evidence

It is generally assumed that ED under the age of 40 is primarily driven by psychosocial factors, whereas ED in older men would be more biologically based.70, 71, 72 Although underlying etiology is important to ensure appropriate management, fragmentation must be averted because ED represents a spectrum with various degrees of psychological and biological involvement.73 In fact, the etiology of ED, even in younger men, is mostly multi-factorial, including a combination of psychological and biological factors.74,75 Other important factors to be considered are ED onset primary (ie, present from the very first sexual contact) or secondary (ie, developed after a period of healthy sexual function) and if ED occurs in all situations or in specific ones. Adding specificity to the diagnosis of ED is important in order to develop more personalized treatment plans.

Sexual orientation is relevant as well. Evidence has shown that the odds of reporting ED are 1.5 times higher in men who have sex with men when compared to heterosexual men.69 Increased feelings of insecurity and performance demand, competition between partners that focus on rigid erections, sexual minority stress, social stigma or internalized homonegativity, in addition to possible organic underlying factors, may all contribute to higher (sexual) distress, which then interferes with the sexual response and vice versa.69 Higher prevalence rates of ED are also found in men with HIV, which could be attributed to organic factors such as the use of protease inhibitor medication inducing androgen deficiency, as well as psychosocial factors such as psychological distress, low social support and discrimination, fear of rejection and fear of transmission.76,77 Similar considerations can be made regarding other important causes of ED where the combination of drugs and feelings of inadequacy along with fear and psychological distress due to body image perturbation (eg, obesity) can profoundly negatively affect sexual function and well-being.78

Several case history tools, including self-reported questionnaires and structured interviews, are available to assess different aspects of ED. Although these inventories have demonstrated their utility in several clinical trials, they cannot be used to replace a full sexual history which remains a crucial step in ED patient evaluation.79

Remarks

Information about sexual health of men who have sex with men or about systematic differences with heterosexual men in terms of prevalence and underlying mechanisms is limited.69 LGBTQI individuals are often excluded in research samples for the purpose of creating homogenous groups. Furthermore, the vast majority of ED case-history tools does not take diversity into account because they are mainly oriented towards heterosexual couples in stable relationship and/or to men who have experienced sexual intercourse in the last 4 weeks preceding the evaluation (eg, International Index of Erectile Function). Such measures are therefore less suited to measure the sexual experiences of single men and men who have sex with men.80, 81, 82

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS: ASSESSMENT OF ED

Statement #4: Clinicians are recommended to proactively ask about sexuality, ED, and treatment options by creating a safe and open environment (Good Clinical Practice Statement).

Statement #5: The assessment of ED requires a medical and psychosexual evaluation as approached from a multidisciplinary perspective (Level 3, Grade 3).

Statement #6: When possible, the partner needs to be involved in the assessment of ED (Level 1, Grade B).

Statement #7: The evaluation of ED should include an assessment of distress (Level 3, Grade 2).

Evidence

Table 1 summarizes the key features of the psychosocial assessment and treatment of ED. Several men experience their health care providers as not approachable enough to talk about sexual issues.83 Furthermore, feelings of shame and embarrassment may prevent men from broaching the topic, with research showing that less than 50% of men talk about ED with their doctor.84 This leaves the responsibility to the health care providers who need to proactively ask about the sexual experiences of their patients and to create an open and safe therapeutic relationship.9,10,13,85,86

Table 1.

Key features of psychosocial assessment and intervention in ED

| Assessment | Intervention | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Factors | Relationship/Partner-related factors⁎ | Individual or with a partner (whenever possible) |

| Etiology from a multidisciplinary perspective: • Medical history • Medical evaluation to screen for vascular, neurologic, hormonal, or medication-induced ED |

Evaluation of co-existence of sexual dysfunction (primary or secondary to men's ED) | Integration of psychological and medical interventions |

| • Determination of specificity • primary vs secondary • situational vs generalized • psychogenic or mixed |

Partner's perception of severity and etiology of partner's ED | Build an atmosphere of trust and safety (good therapeutic alliance) |

| Psychosexual history (sexual development, sexuality education, sexual orientation, body image, history of abuse) | Couple's sexual history and skills | Target unrealistic expectations about treatment |

| Sexual distress and comorbidity with anxiety and depression | Emotional impact of partner's ED and attributions, including guilt, trustfulness and perceptions of self-attractiveness | Use an updated version of the PLISSIT model to guide intervention |

| Evaluation of sexual desire and subjective sexual arousal | Evaluation of couple's communication, sexual self-disclosure and conflict management | Psychoeducation |

| Evaluation of adequate stimulation | Evaluation of both partners’ sexual likes and dislikes | Anxiety reduction and desensitization |

| Sexual beliefs (eg, male performance beliefs) | Partner's own sexual beliefs (eg, about men´s sexual performance) | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, (including third wave approaches such as mindfulness) Consider internet-delivered interventions |

| Attentional processes (eg, cognitive distraction, automatic thoughts) | Willingness to be involved in and expectations about treatment | Increasing sexual stimulation |

| Traits /personality factors (eg, perfectionism, negative affect, neuroticism) | Expanding on sexual quality instead of quantity and adjusting expectations (Good Enough Sex Model) | |

| Questionnaires, including a measure of distress | Include pleasure and/or satisfaction as treatment outcome | |

| Previous attempts to solve the problem, expectations about current intervention | ||

| Involvement of partner | ||

| Barriers to treatment: • Feeling embarrassed • Low self-confidence • Self and partner blaming • Feeling older • Communication problems between partners • Inaccurate information and limited understanding of ED • Stigma about ED • Unrealistic expectations about treatment |

||

| Facilitators of treatment: • Desire to have sex • Partner's compliance • Awareness of treatment options and affordability of treatment |

||

Notes: This table assumes distress associated with the experience of ED. This table centers on psychosocial factors and therefore excludes medical/organic factors. The authors acknowledge that a multidisciplinary integrative approach to ED is necessary.

These factors can be evaluated with the patient or, ideally, with the partner present.

The assessment of ED traditionally starts with a careful medical history along with a physical examination, combined with specific lab testing (eg, hormone, glucose, and lipid levels).10,87 Given the involvement of psychosocial factors in the etiology of ED, it should be standard practice to take a detailed psychosexual history that focuses on the cognitive, emotional, and relational experiences associated with ED.7,10,88 Special attention is needed to identify the presence of adequate sexual stimuli and to explore whether the current sexual script (ie, the couple's ideas and expectations of how the couple should behave in sexual or romantic situations) is still satisfying to elicit sexual arousal. Medical specialists, however, may often lack the knowledge and skills to evaluate key psychological determinants of ED.89 It is therefore important to update the university curricula of physicians to include biopsychosocial knowledge of sexual health issues as well as to team up with a sexologist to assess (and treat) ED from a multidisciplinary perspective. It is noteworthy that the Multidisciplinary Committee of Sexual Medicine (MJCSM) does strongly promote such multidisciplinary view.90

In addition, it is important to include, whenever applicable and possible, the partner during the assessment procedure because (s)he may be aware of the problem first as men tend to ignore or suppress the problem, even when feeling distressed.49,52,53 Not only does the partner often know more about the circumstances in which the ED occurs, (s)he may also play an important role in motivating the partner to consider treatment. Moreover, the partner's attitude and understanding of ED has been found to influence the decision to seek treatment and agreement between both partners about the choice of treatment would even predict treatment outcome and adherence.91

As a final consideration on the assessment of ED, we mention the importance of including a distress measure because an erectile problem qualifies only as a dysfunction requiring treatment when it provokes feelings of distress.7 Note that, from a clinical point of view, the presence of distress without a clear ED diagnosis has to be considered as well.92,93 At present, few questionnaires are available to assess distress. The Female Sexual Distress Scale and its revisions have been validated for use in a population of females92 or female partners of males suffering from premature ejaculation,94 but more specific measures are needed that take into account the (possible changes in the) meaning of ED over the course of life. As the prevalence of ED increases with age, the level of distress caused by the ED does not follow the same linear sequence. Hence, older men may experience severe levels of impaired sexual function without significant distress.72 Age should be taken into account when proposing a treatment because lack of motivation may interfere with treatment adherence or may cause men to decide not to pursue any treatment at all.83,95

PSYCHOLOGICAL TREATMENT OF ED

Statement #8: Clinicians are recommended to assess barriers for ED treatment such as low self-confidence, embarrassment, communication problems between partners, stigma related to ED and its treatment (Good Clinical Practice Statement).

Evidence

Research has identified several barriers to seeking treatment for ED. In addition to feeling embarrassed, communication problems between partners, low self-confidence, self and partner blaming, and feeling older, also inaccurate information and limited understanding of ED may prevent men and their partners from seeking help.59,96,97 Other barriers to treatment are unrealistic expectations about treatment possibilities and stigma around sexuality in later life as well as stigma related to ED treatment, particularly regarding the use of medication.56 Moreover, health care professionals’ gender and communication style seem to have an effect on men's disclosure about ED.98 Indicators for seeking treatment, on the other hand, are desire to have sex, duration of the condition, partner insistence, awareness of treatment options, and affordability of treatment.96,97 Health care professionals need to be aware of and assess indicators and contra-indicators of help-seeking behavior in order to proactively inform and counsel men with ED, promote treatment adherence, and guide future management.

The medical treatment of ED follows a stepwise program, moving from less invasive treatments such as lifestyle changes, pelvic floor exercises, and medication (changes) to more invasive modalities such as the use of mechanical devices, intracavernous injections, and surgical implantation of a penile prosthesis.9, 10, 11, 12 Although medical treatments have been shown to be physiologically effective, long-term adherence to medical treatment is poor and erectile function recovery is not always achieved, often depending on how well men are instructed about (correct) use of the medical aids.99, 100, 101 Research has shown that more than 50% of the couples do not adhere to medical aids for erectile function after the first year of treatment.99,100,102 This often culminates in complete avoidance of sexual activity, which may eventually damage the structure and physiological mechanism of the penis and negatively affect the emotional state of men and their partner. Although more work is needed to identify the exact reasons for treatment drop-out, there is a possible role of treatment costs and side-effects, recovery of natural erectile capability, lack of interest in sexual activity, lack of spontaneity and artificial intimacy associated with the use of sexual aids, embarrassment, new demands that induce performance anxiety, unrealistic expectations, and relational issues such as communication problems, lack of confidence, and lack of partner suppor.t95,96 Furthermore, focusing only on the functional aspects of erectile function and disregarding the role of sexual stimulation and/or the meaning of ED for the couple may interfere with treatment success and adherence. Most of the aforementioned variables refer to psychosocial issues, which indicates the need to combine medical treatments with psychological treatment in order to target the psychological and relational aspects of ED that are left untreated when relying on a purely symptomatic management.

A distinction can be made between counselling and psychotherapy, with counselling referring to providing support and guidance, raising awareness, and giving limited advices with regard to specific (present) issues, so the patient can figure out better ways to manage the ED. Psychotherapy, on the other hand, goes 1 step further and is directed towards gaining insights into chronic and recurrent emotional and cognitive patterns, often established by past events, and how these may cause the current problems.102 Sex therapy can be regarded as a specific type of psychotherapy, focusing specifically on sexual experiences.103 Because there is no clear evidence on which type of psychological treatment is better suited for which type or stage of ED, we refer to psychological treatment in general when describing the evidence on treatment.

THE MANAGEMENT OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TREATMENT

In the following sections, we will provide a more specific analysis of various issues related to the psychological treatment of ED patients.

General Considerations

Statement #9: A multidisciplinary treatment, in which medical treatment is combined with psychological treatment, has proven to be more effective than mono-treatment (Level 2, Grade B).

Statement #10: The biopsychosocial model is recommended because biological, psychological and relational factors are typically at play in the development and maintenance of ED (Level 5).

Evidence

Medical treatments, especially pharmacotherapy, are often viewed as more effective and cost-efficient than psychological treatments because the latter raise uncertainty about treatment duration and outcome.49,87,104,105 As a result, medical treatments are often applied regardless of cause or status of the partner relationship. The patients themselves may also prefer a medical treatment over psychological treatment because they consider the use of medication or other sexual aids as a quick fix and less invasive than being exposed to emotional and relational issues.105 Available evidence shows that combining medical treatment with psychotherapy increases its effectiveness in terms of better outcomes and less drop-out, even when a clear organic cause has been established.106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112

Psychological treatment may help to promote treatment adherence, integrate the treatment (ie, medical aids) into the sexual relationship and resolve psychological correlates such anxiety, negative thoughts, distress, self-confidence, intimacy, and communication problems between partners.59,109 Furthermore, psychological treatment can prevent the recurrence of the sexual problem after treatment because men learn to manage their dysfunctional response patterns associated with ED.108 Hence, whereas medical treatments are directed towards treating the symptoms, that is, restoring erection, psychological treatment targets the underlying causes, maintaining factors, and subjective experiences. Medical treatment is, however, not only indicated in case of organic ED. PDE5 inhibitors, for example, can be used in case of psychologic ED as well to reduce failure anxiety and increase self-confidence as a first step to regain control over their erectile function.113,114 Hence, it can be stated that the treatment of ED is not cause-specific.12

Remarks

Although the past decade marks a clear shift towards a multicausal and multi-dimensional conceptualization and treatment of sexual dysfunctions, the implementation of interdisciplinary referral networks and multidisciplinary treatments is still a challenge.89 Unimodal treatment algorithms may be conceptually condemned but remain common practice. This tension between theory and practice of biopsychosocial sexual health care may result from insufficient knowledge and lack of explicit clinical guidelines on how to set up and implement an integrated treatment program. Limitations in training curricula and structural obstacles may prevent the actual implementation of the biopsychosocial model.89 In addition, available studies on the effectiveness of psychological treatments are limited and hampered by small samples sizes, inadequate follow-up, and a lack of controlled designs.106, 107, 108 Sexual health organizations should therefore invest more in offering trainings in biopsychosocial practice, developing biopsychosocial treatment manuals, and promoting RCT's on the effectiveness of integrated combination treatments. ESSM is actively working towards these aims.115

Practical Approach

The Importance of Age

Statement #11: Clinical management of ED should be tailored according to different ages (Level 4, Grade C).

Evidence

Because young men with ED report higher levels of distress and less satisfaction, they have a special need for psychological treatment.116,117 Older men, on the other hand, are more likely to accept their ED as a normal part of aging, which might be a barrier to seeking help. Although men typically report less distress about changes in their sexual life as they grow older, stigma around sexuality in later life may confuse them about the impact of the sexual problem on their well-being.83,117,118 Proactive counselling by health care providers is important to help older men with admitting the problem, exploring its impact on their (sexual) well-being, and overcoming barriers to seeking treatment when feeling distressed about the ED.

The Importance of Shared Decision-Making

Statement #12: The choice of treatment should involve a shared decision between patient, partner, and health professional (Level 2, Grade B).

Evidence

Patients and their partner should be informed about all treatment options to ensure a full understanding of potential risks, benefits, indications, contra-indications, and desired outcomes. Not only does shared decision-making increase patient autonomy, it also predicts a better course, adherence, and outcome of therapy because patients have more realistic treatment expectations.10, 11, 12

The Specifics of Psychological Treatment

Statement #13: Psychological treatment follows a stepwise program, according to the PLISSIT model (Level 4, Grade C).

Statement #14: Clinicians are recommended to provide an accurate and meaningful explanation of the problems and suggested treatment plan (Good Clinical Practice Statement).

Statement #15: Psychological treatment involves reducing anxiety, challenging cognitive beliefs, increasing sexual stimulation, disrupting sexual avoidance, and interpersonal interventions such as communication skills training (Level 2, Grade B).

Statement #16: It is recommended to include the partner in ED treatment to promote treatment adherence, increase treatment success, and to target the partner's own psychological and sexual problems and distress (Level 2, Grade B).

Evidence

The PLISSIT is a useful model to determine the different levels of intervention for sexual problems.119 This stepwise intervention approach ensures that the treatment is better tailored to the patient's current needs and will therefore be more readily accepted by patients. The first level of intervention involves giving patients the Permission to talk about their sexual concerns by creating an open, receptive, and nonjudgmental therapeutic climate. In later years, the PLISSIT model has been updated to emphasize that permission is an important aspect throughout different levels of intervention.120 Once the sexual concerns have been identified, Limited and specific Information is given about etiology, underlying mechanisms, and outcome. If indicated, Specific Suggestions are offered to deal with the sexual problem, including information and homework assignments to introduce behavioral changes, specific sexual activities, and/or medications. The fourth and final level offers Intensive Therapy when deeper underlying issues and concerns are at play. A referral can be made to, for example, a psychotherapist to provide more comprehensive support and guidance. The PLISSIT model not only gives direction to sexologists, it also offers an accessible method for introducing sexual themes into a medical consultation, narrowing the scope of a patient's concern, and referring for additional treatment when a patient's needs exceed the clinician's comfort, knowledge, and time.

Psychological treatment acts on these different levels of intervention and starts with exploring the patient's request for help to determine whether treatment is motivated by self-related concerns, partner pressure, or relational issues. It is also important to tackle unrealistic treatment expectations to prevent treatment drop-out and dissatisfaction. Building an emotional bond of trust, care, and respect between therapist and patient is essential because the quality of the therapeutic relationship has shown to be a significant predictor of treatment success.121 Psychological treatment programs commonly include the following components: psychoeducation; anxiety reduction and desensitization; cognitive therapy and sexual fantasy training; increasing sexual stimulation; and couple interventions.4,108,122

Psychoeducation is a necessary first step to increase knowledge about the sexual response and ED, and to increase comfort to openly talk about sex. In particular, the main aim of psychoeducation is to offer to the patients and their partner clear documentation regarding the problem and its etiology, and on the possible repercussions ED may have on both the intrapsychic and relational aspects. This is followed by a combination of cognitive and behavioral interventions to tackle the failure anxiety, performance anxiety, and avoidance of sexual intimacy that is characteristic of ED. A technique often used in classical sex therapy is sensate focus.122,123 These exercises progress from nongenital touching to genital touching, while being instructed not to pursue sexual arousal and to refrain from penetration. This technique, associated with the desensitization, which prevents the patient's anxiety related to intercourse shows to the patients and their partners that pleasurable sex can occur in the absence of genital arousal, drawing the focus away from goal-directed sex. Once the male patient has learned to keep his attention to his bodily sensations and to become less distracted by performance demands or anxiety, and once he has gradually re-build self-confidence, penetration is re-introduced in a step-by-step fashion. An additional benefit of sensate focus is that couples learn to schedule instances of intimacy, by preference 2 times a week and each 10 minutes, thereby challenging the myth of spontaneous sex. That is, sexual desire does not emerge spontaneously, but requires conscious effort, planning, and an intimate context to create opportunities for having sex.16,17 Furthermore, by switching between the active and passive role, men gain experience with both giving and receiving sexual stimulation.

These homework assignments are regularly combined with cognitive interventions that challenge dysfunctional beliefs and expectations and aim at replacing these with more helpful thoughts.21,24,26 In addition, men are prompted to search for new and extra sexual stimulation in order to vary and broaden their sexual script. This also involves nonintercourse forms of sexual stimulation to decrease their focus on penetration.61 The treatment of ED, especially in older men, also consists of learning men and their partner to increase genital stimulation by applying more, longer, and more direct stimulation to the penis. Masturbation training using maximal (eg, vibrotactile) stimulation and guided sexual fantasy training may also help men to gain control over their erection while experiencing maximum levels of sexual arousal. In light of the increased medicalization of ED, it is important to make couples realize that sex not always has to be perfect nor that it requires a firm erection all the time.124,125 Intimacy, sexual pleasure, and emotional acceptance are as important as sexual function, and the quality of sexual interactions is likely to vary from day to day. This implies that couples need to accept that less satisfying experiences are common and thus quite normal. Explaining the Good Enough Sex Model may help couples to embrace sexual satisfaction instead of capitulating under the pressure of sexual performance and to encourage them to pursue more realistic expectations about sex.125,126

It is highly recommended to, when applicable and possible, include the partner in the treatment of ED. Both partners suffer from the problem, and it has been shown that positive involvement of the partner helps to solve the problem and adhere to treatment.49,52,54,99 Furthermore, sexual partners may need counselling too because the ED may cause them to feel sexually unattractive, induce feelings of guilt and rejection, generate relational distress, and interfere with their own sexual function.14,54,55 Research has shown that ED treatment improves the partner's sexual function and satisfaction as well, indicating the importance of including couple interventions.50,64,127 A key component of the systemic approach to ED is improving the communications kills of both partners and learning them to openly talk about their likes and dislikes, what the ED means to them, how a satisfying sex life would look like, and how to integrate medical aids (when needed) in their sexual script.57, 58, 59 In addition, therapy should identify and treat underlying relational dynamics because relationship conflicts are an important reason for lack of compliance or drop-out.59,99

New Developments

Statement #17: New developments in ED treatment that target the body-mind connection or promote acceptance and rely on new treatment modalities such as internet-based therapy are promising (Level 4, Grade C).

Evidence

Although traditional CBT models remain popular, interest in alternative treatments of ED is rapidly growing. New developments in clinical psychology have found their way to the treatment of sexual dysfunctions. Among these, mindfulness-based interventions have become increasingly popular as their effectiveness have been demonstrated for a range of clinical problems.127, 128, 129 Mindfulness is rooted in Buddhist meditation and cultivates nonjudgmental moment-to-moment awareness by learning to decenter thoughts and feelings and focus attention on bodily sensations instead. In the context of ED, mindfulness may reduce anxiety, spectatoring, and self-evaluation and help to redirect attention to physical and erotic sensations instead of cognitive distractors.130 Recent studies have suggested that mindfulness holds promise as a treatment of ED, particularly when applied in a group therapy format.131 A treatment protocol based on daily home-practice activities and integrated elements of psychoeducation, sex therapy, and mindfulness skills has shown to improve communication and intimacy with the partner and increase self-efficacy by learning tools to cope with their ED. Although self-reported erectile function did not change immediately after treatment, men were found to report more satisfaction, sexual pleasure, and better coping/management of ED.131

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is another promising treatment that promotes acceptance of thoughts, sensations, and feelings.132,133 ACT targets ineffective control strategies and experiential avoidance and focuses on the patient's ability to identify and commit to valued goals in daily life.124 Acceptance of erectile difficulties includes giving up efforts to reduce and control the ED and to fully engage in the activities and relationships that are in line with personal values. Although there is no evidence yet to support the effectiveness of ACT in the context of ED, a treatment based on acceptance may be particularly relevant in cases where chances of erectile recovery are low (eg, prostate cancer patients).

With the surge of internet usage and online applications, sexual medicine has started to explore the feasibility of internet-administered treatments of sexual dysfunctions.134 Although more work is needed to establish the effectiveness of e-health, there are first indications that a CBT internet-intervention based on weekly information and homework assignments delivered via the internet and contact with the therapist via email (on request), showed greater improvements in erectile function compared to a control group that participated in online discussions.135 Several other internet-based interventions for ED have also proven to be effective.136,137 In general, internet-based psychological treatments are believed to be more cost-effective and readily accessible than traditional treatment modalities, thereby overcoming common barriers to seeking help such as shame, difficulties with face-to-face communication about sex, time limits, costs, or geographical distance.138 Although drop-out was high during the 7-weeks program, e-health might offer new opportunities to help those patients who are less easy to reach but would nevertheless benefit from sex-therapeutical treatment.135,139

Treatment Outcomes

Statement #18: Outcome variables should focus on satisfaction, pleasure, and quality instead of quantity of sexual activity (Level 5).

Evidence

As a concluding remark on the treatment of ED, we want to emphasize the importance of considering broader outcome variables that measure beyond erectile function when evaluating treatment effects and to focus more on sexual pleasure and satisfaction. A narrow focus on genital function or performance disregards the broader relational context and psychological variables that constitute a patient and partner's sexual satisfaction and quality of life.14,124,140 Psychological treatment mainly acts on the psychosocial correlates of ED, aiming to lower the distress associated with ED, increase self-confidence, expand sexual stimulation, improve sexual function, and install better coping and management of ED. Function-focused end points are less attuned to these subjective changes and thus less valid to capture specific treatment benefits. Furthermore, the clinical relevance of changes in erectile function may be questioned if not accompanied by clinically meaningful improvements in overall sexual satisfaction and pleasure.140 Although an evaluation of erectile function remains important, treatment effect studies should also include subjective and person-centered outcomes such as level of satisfaction with erectile function, quality instead of quantity of sexual activity, sexual confidence, quality of sexual life, and level of intimacy between partners.

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of ED needs to be approached from a multidisciplinary perspective that takes into account the diverse and biopsychosocial nature of erectile function. To ensure a better integration of the biopsychosocial model into clinical practice, it is recommended to invest more in developing concrete treatment protocols and training programs. Clinicians also need specific training to proactively ask about sexual health issues in order to create an open and inviting atmosphere to talk about sexuality. Given that ED often occurs during sexual interactions, it is essential to include the partner, when applicable and possible, in all phases of clinical care and to actively work on interpartner agreement and shared decision-making regarding possible treatment options. In general, the sexual medicine field needs to evolve towards becoming more diverse and inclusive. This can be realized by promoting new types and modalities of treatment that target the body-mind connection and include e-health, sampling both heterosexual men and LGBTQI+ individuals with ED in different relationship structures and with a different relationship status, testing the effectiveness of combined treatments over mono-treatment, and considering more diverse and subjective end points of treatment that include sexual satisfaction and distress instead of focusing solely on erectile function.

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

Marieke Dewitte: Writing -original draft; Carlo Bettocchi: Writing -editing; Joanna Carvalho: Writing -editing; Giovanni Corona: Writing -editing; Ida Flink: Writing -editing; Erika Limoncin: Writing -editing; Patricia Pascoal: Writing -editing; Yacov Reisman: Writing -editing; Jacques Van Lankveld: Writing -editing.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: None.

References

- 1.Rosen RC, Fisher WA, Eardley I, et al. The multinational Men's Attitudes to Life Events and Sexuality (MALES) study: I. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction and related health concerns in the general population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:607–617. doi: 10.1185/030079904125003467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laumann EO, Glasser DB, Neves RC, et al. A population-based survey of sexual activity, sexual problems and associated help-seeking behavior patterns in mature adults in the United States of America. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21:171–178. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2009.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler A, Sollie S, Challacombe B, et al. The global prevalence of erectile dysfunction: A review. BJU Int. 2019;124:587–599. doi: 10.1111/bju.14813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCabe MP, Connaughton C. Psychosocial factors associated with male sexual difficulties. J Sex Res. 2014;51:31–42. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.789820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corona G, Ricca V, Bandini E, et al. SIEDY scale 3, a new instrument to detect psychological component in subjects with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2012;9:2017–2026. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCabe MP, Althof SE. A systematic review of the psychosocial outcomes associated with erectile dysfunction: does the impact of erectile dysfunction extend beyond a man's inability to have sex? J Sex Med. 2014;11:347–363. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephenson KR, Truong L, Shimazu L. Why is impaired sexual function distressing to men? Consequences of impaired male sexual function and their associations with sexual well-being. J Sex Med. 2018;15:1336–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boddi V, Corona G, Fisher AD, et al. It Takes Two to Tango": The relational domain in a cohort of subjects with erectile dysfunction (ED) J Sex Med. 2012;9:3126–3136. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salonia A, Bettocchi C, Carvalho J, et al. EAU Guidelines on Sexual and reproductive Health. 2020. Available at: https://uroweb.org/guideline/sexual-and-reproductive-health. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- 10.American Urological Association. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guidelines. 2021. Available at: https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/erectile-dysfunction-(ed)-guideline. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- 11.Shamloul R, Ghanem H. Erectile dysfunction. Lancet. 2013;381:153–165. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnett AL, Nehra A, Breau RH, et al. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2018;200:633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulhall J, Althof SE, Brock GB, et al. Erectile dysfunction: monitoring response to treatment in clinical practice—Recommendations of an international study panel. J Sex Med. 2007;4:448–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brotto L, Atallah S, Johnson-Agbakwu C, et al. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2016;13:538–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen E, Everaerd W, Spiering M, et al. Automatic processes and the appraisal of sexual stimuli: Towards an information processing model of sexual arousal. J Sex Res. 2000;37:8–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Both S, Everaerd W, Laan E. In: The psychophysiology of sex. Janssen E., editor. Indiana University Press; Bloomington: 2017. Desire emerges from excitement: a psychophysiological perspective on sexual motivation. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toates F. An integrative theoretical framework for understanding sexual motivation, arousal, and behavior. J Sex Res. 2009;46:168–193. doi: 10.1080/00224490902747768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarin S, Amsel R, Binik YM. How Hot Is He? A psychophysiological and psychosocial examination of the arousal patterns of sexually functional and dysfunctional men. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1725–1740. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barlow DH. Causes of sexual dysfunction: The role of anxiety and cognitive interference. J Cons Clin Psych. 1986;54:140–148. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowland DL, Myers AL, Adamski BA, et al. Role of attribution in affective responses to a partnered sexual situation among sexually dysfunctional men. BJUI Int. 2012;111:e103–e109. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giuri S, et al. Cognitive attentional syndrome and metacognitive beliefs in male sexual dysfunction: an exploratory study. Am J Men's Health. 2017;11:592. doi: 10.1177/1557988316652936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rozental A, Andersson G, Carlbring P. In the absence of effects: an individual patient data meta-analysis of non-response and its predictors in internet-based cognitive behavior therapy. Front Psychol. 2019;10:589. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nobre P. Psychological determinants of erectile dysfunction: Testing a cognitive–emotional model. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1429–1437. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nobre PJ, Pinto-Gouveia J. Dysfunctional sexual beliefs as vulnerability factors to sexual dysfunction. J Sex Res. 2006;43:68–75. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nobre PJ, Pinto-Gouveia J. Emotions during sexual activity: Differences between sexually functional and dysfunctional men and women. Arch Sex Beh. 2006;3:8–15. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nobre P, Gouveia JP. Erectile dysfunction: An empirical approach based on Beck's cognitive theory. Sex Rel Ther. 2000;15:351–366. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zilbergeld B. In: Erectile disorders: Assessment and treatment. Rosen R.C., Leiblum S.R., editors. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1992. The man behind the broken penis: Social and psychological determinants of erectile failure; pp. 27–55. 1st ed. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zilbergeld B. (rev. ed.) Bantam Books; New York, NY: 1999. The new male sexuality. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scepkowsky L, Wiegel M, Bach A, et al. Attributions for sexual situations in men with and without erectile disorder: Evidence from a sex-specific attributional style measure. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;33:559–569. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000044740.72588.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowland DL, Adamski BA, Neal CJ, et al. Self-efficacy as a relevant construct in understanding sexual response and dysfunction. J Sex Mar Ther. 2015;41:60–71. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2013.811453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowland DL, Kostelyk KA, Tempel AR. Attribution patterns in men with sexual problems: Analysis and implications for treatment. Sex Rel Ther. 2016;31:148–158. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen BL, Cyranowski JM, Espindle D. Men's sexual self- schema. J Pers Soc Psych. 1999;76:645–661. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Althof SE. Quality of life and erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2002;59:803–810. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pascoal PM, Raposo CF, Oliveira LB. Predictors of body appearance cognitive distraction during sexual activity in a sample of men with ED. Int J Impot Res. 2015;27:103–107. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2014.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geer JH, Fuhr R. Cognitive factors in sexual arousal: The role of distraction. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1976;4:238–243. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.44.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quinta Gomes AL, Nobre P. Personality traits and psychopathology on male sexual dysfunction: An empirical study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:461–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen MS, Walter EE. Linking big five personality traits to sexuality and sexual health: A meta-analytic review. Psych Bull. 2018;144:1081–1110. doi: 10.1037/bul0000157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bancroft J. Central inhibition of sexual response in the male: A theoretical perspective. Neurosci Biobehav R. 1999;23:763–784. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bancroft J, Janssen E. The dual control model of male sexual response: A theoretical approach to centrally mediated erectile dysfunction. Neurosci Biobehav R. 2000;24:571–579. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bancroft J, Herbenick D, Barnes T, et al. The relevance of the dual control model to male sexual dysfunction: The Kinsey Institute BASRT Collaborative Project. Sex Rel Ther. 2005;20:13–30. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corona G, Rastrelli G, Balercia G, et al. Perceived reduced sleep-related erections in subjects with erectile dysfunction: Psychobiological correlates. J Sex Med. 2011;8:1780–1788. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mallis D, Moysidis K, Hatzichristou D. Expressions of anxiety in patients with erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14:S87. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corona G, Mannucci E, Petrone L, et al. Psycho-biological correlates of free-floating anxiety symptoms in male patients with sexual dysfunctions. J Androl. 2006;27:86–93. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.05070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Araujo AB, Durante R, Feldman HA, et al. The relationship between depressive symptoms and male erectile dysfunction: Cross-sectional results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:458–465. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199807000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atlantis E, Sullivan T. Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1497–1507. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Q, Zhang Y, Wang J, et al. Erectile dysfunction and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2018;15:1073–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montjo-Gonzales A, Llorce G, Izquierdo J, et al. SSRI – induced sexual dysfunction: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertaline and fluvoxamine in a prospective, multicenter, and descriptive clinical study of 344 patients. J Sex Marital Ther. 1997;23:176–187. doi: 10.1080/00926239708403923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montejo AL, Montejo L, Navarro-Cremades F. Sexual side-effects of antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:418–423. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosen R, Janssen E, Wiegel M, et al. Psychological and interpersonal correlates in men with erectile dysfunction and their partners: A pilot study of treatment outcome with sildenafil. J Sex Mar Ther. 2006;32:215–234. doi: 10.1080/00926230600575314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corona G, Petrone L, Mannucci E, et al. Assessment of the relational factor in male patients consulting for sexual dysfunction: The concept of couple sexual dysfunction. J Androl. 2006;27:795–801. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dewitte M. On the interpersonal dynamics of sexuality. J Sex Mar Ther. 2014;40:209–232. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2012.710181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiann BP, Su CC, Tsai JY. Is female sexual function related to the male partners’ erectile function? J Sex Med. 2013;10:420–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.03007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fisher WA, Rosen RC, Eardley I, et al. Sexual experience of female partners of men with erectile dysfunction: The female experience of men's attitudes to life events and sexuality (FEMALES) study. J Sex Med. 2005;2:675–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li H, Gao R, Wang R. The role of the sexual partner in managing erectile dysfunction. Nat Rev Urol. 2016;13:168–177. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2015.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chevret M, Jaudinot E, Sullivan K, et al. Impact of erectile dysfunction (ED) on sexual life of female partners: Assessment with the Index of Sexual Life (ISL) questionnaire. J Sex MaritalTher. 2004;30:157–172. doi: 10.1080/00926230490262366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McGraw SA, Rosen RC, Althof SE, et al. Perceptions of erectile dysfunction and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy in a qualitative study of men and women in affected relationships. J Sex Marital Ther. 2015;41:203–220. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2013.864368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacNeil S, Byers ES. Role of sexual self-disclosure in the sexual satisfaction of long-term heterosexual couples. J Sex Res. 2009;46:3–14. doi: 10.1080/00224490802398399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacNeil S, Byers ES. The relationships between sexual problems, communication, and sexual satisfaction. Can J Hum Sex. 1997;6:277–283. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Conaglen HM, Conaglen JV. Couples' reasons for adherence to, or discontinuation of, PDE type 5 inhibitors for men with erectile dysfunction at 12 to 24-month follow-up after a 6-month free trial. J Sex Med. 2012;9:857–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jannini EA, Sternbach N, Limoncin E, et al. Health-related characteristics and unmet needs of men with erectile dysfunction: A survey in five European countries. J Sex Med. 2014;11:40–50. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wassersug R, Wibowo E. Non-pharmacological and non-surgical strategies to promote sexual recovery for men with erectile dysfunction. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6:S776–S794. doi: 10.21037/tau.2017.04.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Speckens AEM, Hengeveld MW, Lycklama à Nijeholt G, et al. Psychosexual functioning of partners of men with presumed non-organic erectile dysfunction: Cause or consequence of the disorder? Arch Sex Bev. 1995;24:157–172. doi: 10.1007/BF01541579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCabe MP. Intimacy and quality of life among sexually dysfunctional men and women. J Sex Marital Ther. 1997;23:276–290. doi: 10.1080/00926239708403932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chevret-Méasson M, Lavallée E, Troy S, et al. Improvement in quality of sexual life in female partners of men with erectile dysfunction treated with sildenafil citrate: Findings of the Index of Sexual Life (ISL) in a couple study. J Sex Med. 2009;6:761–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McCabe MP, Matic H. Erectile dysfunction and relationships: Views of men with erectile dysfunction and their partners. Sex Rel Ther. 2008;23:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Metz ME, Epstein N. Assessing the role of relationship conflict in sexual dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28:139–164. doi: 10.1080/00926230252851889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boddi V, Fanni E, Castellini G, et al. Conflicts within the family and within the couple as contextual factors in the determinism of male sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2015;12:2425–2435. doi: 10.1111/jsm.13042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peixoto MM, Nobre P. “Macho” beliefs moderate the association between negative sexual episodes and activation of incompetence schemas in sexual context, in gay and heterosexual men. J Sex Med. 2017;14:518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barbonetti A, D'Andrea S, Cavallo F, et al. Erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation in homosexual and heterosexual men: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Sex Med. 2019;16:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nguyen HMT, Gabrielson AT, Hellstrom WJG. Erectile Dysfunction in young men—A review of the prevalence and risk factors. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5:508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tutino JS, Shaughnessy K, Ouimet AJ. Looking at the bigger picture: Young men's sexual health from a psychological perspective. J Health Psychol. 2018;23:345–358. doi: 10.1177/1359105317733321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corona G, Rastrelli G, Maseroli E, et al. Sexual function of the ageing male. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27:581–601. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jannini EA, McCabe MP, Salonia A, et al. Organic vs. psychogenic? The Manichean diagnosis in sexual medicine. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1726–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Burnett A. In: Campbell-Walsh urology. McDougal, Wein, Kavoussi, et al., editors. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2011. Evaluation and management of erectile dysfunction; pp. 126–128. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mialon A, Berchtold A, Michaud PA, et al. Sexual dysfunctions among young men: Prevalence and associated factors. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huntingdon B, Muscat DM, de Wit J, et al. Factors associated with erectile dysfunction among men living with HIV: A systematic review. AIDS Care. 2019;32:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1653443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Santi D, Brigante G, Zona S, et al. Male sexual dysfunction and HIV – A clinical perspective. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:99. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2013.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yafi FA, Jenkins L, Albersen M, et al. Erectile dysfunction. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16003. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Corona G, Jannini EA, Maggi M. Inventories for male and female sexual dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18:236–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–830. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rynja S, Bosch R, Kok E, et al. IIEF-15: Unsuitable for assessing erectile function of young men? J Sex Med. 2010;7:2825–2830. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01847.x. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Forbes MK, Baillie AJ, Schniering CA. Critical flaws in the female sexual function index and the international index of erectile function. J Sex Res. 2014;51:485–491. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.876607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sinković M, Towler L. Sexual aging: A systematic review of qualitative research on the sexuality and sexual health of older adults. Qual Health Res. 2019;29:1239–1254. doi: 10.1177/1049732318819834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marwick C. Survey says patients expect little help on sex. JAMA. 1999;281:2173–2174. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.23.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Horvath AO, Del Re AC, Fluckiger C, et al. Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy. 2011;48:9–16. doi: 10.1037/a0022186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lafrenaye-Dugas AF, Martine Hébert M, Godbout N. Sexual satisfaction improvement in patients seeking sex therapy: Evaluative study of the influence of traumas, attachment and therapeutic alliance. Sex Rel Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1080/14681994.2020.1726314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mulhall JP, Giraldi A, Hackett G, et al. The 2018 revision to the process of care model for evaluation oferectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2018;15:1280–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hatzichristou D, Kirana PS, Banner L, et al. Diagnosing sexual dysfunction in men and women: Sexual history taking and the role of symptom scales and questionnaires. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1166–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Berry MD, Berry PD. Contemporary treatment of sexual dysfunction: Reexamining the biopsychosocial model. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2627–2643. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eardley I, Reisman Y, Goldstein S, et al. Existing and future educational needs in graduate and postgraduate education. J Sex Med. 2017;14:475–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fisher WA, Eardley I, McCabe M, et al. Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a shared sexual concern of couples II: Association of female partner characteristics with male partner ED treatment seeking and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor utilization. J Sex Med. 2009;6:3111–3124. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Santos-Iglesias P, Mohamed B, Walker LM. A systematic review of sexual distress measures. J Sex Med. 2018;15:625–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jannini EA, Lenzi A, Isidori A, et al. Subclinical erectile dysfunction: Proposal for a novel taxonomic category in sexual medicine. J Sex Med. 2006;3:787–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Limoncin E, Tomassetti M, Gravina GL, et al. Premature ejaculation results in female sexual distress: Standardization and validation of a new diagnostic tool for sexual distress. J Urol. 2013;189:1830–1835. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Walther A, et al. Psychobiological protective factors modifying the association between age and sexual health in men: Findings from the Men's Health 40+ Study. Am J Men Health. 2017;11:737. doi: 10.1177/1557988316689238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Berner MM, Ploger W, Burkart M. A typology of men's sexual attitudes, erectile dysfunction treatment expectations and barriers. Int J Imp Res. 2007;19:568–576. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shabsigh R, Perelman MA, Laumann EO, et al. Drivers and barriers to seeking treatment for erectile dysfunction: A comparison of six countries. BJU Int. 2004;94:1055–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rastrelli G, Cipriani S, Craparo A, et al. The physician’s gender influences the results of the diagnostic workup for erectile dysfunction. Andrology. 2020;8:671–679. doi: 10.1111/andr.12759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Carvalheira AA, Pereira NM, Maroco J, et al. Dropout in the treatment of erectile dysfunction with PDE5: A study on predictors and a qualitative analysis of reasons for discontinuation. J Sex Med. 2012;9:2361–2369. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Limoncin E, Gravina GL, Corona G, et al. Erectile function recovery in men treated with phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor administration after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: A systematic review of placebo-controlled randomized trials with trialsequential analysis. Androl. 2017;5:863–872. doi: 10.1111/andr.12403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Klotz T, Mathers M, Klotz R, et al. Why do patients with erectile dysfunction abandon effective therapy with sildenafil (Viagra)? Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:2–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sharf RS. Cengage Learning; 2015. Theories of psychotherapy and counseling: Concepts and cases. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Bantam Books; New York: 1970. Human sexual inadequacy. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Allen MS, Walter EE. Erectile dysfunction: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of risk-factors, treatment, and prevalence outcomes. J Sex Med. 2019;16:531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.01.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ciocanel O, Power K, Eriksen A. Interventions to treat erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation: an overview of systematic reviews. Sex Med. 2019;7:251–269. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Frühauf S, Gerger H, Schmidt HM, et al. Efficacy of psychological interventions for sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:915–933. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Günzler C, Berner MM. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in men and women with sexual dysfunctions—A systematic review of controlled clinical trials: Part 2—The efficacy of psychosocial interventions for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2012;9:3108–3125. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Berner M, Günzler C. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in men and women with sexual dysfunctions–A systematic review of controlled clinical trials: Part 1-The efficacy of psychosocial interventions for male sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2012;9:3089–3107. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schmidt HM, Munder T, Gerger H, et al. Combination of psychological intervention and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunction: A narrative review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1376–1391. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Khan S, Amjad A, Rowland D. Potential for long-term benefit of cognitive behavioral therapy as an adjunct treatment for men with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2019;16:300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Corona G, Rastrelli G, Burri A, et al. First-generation phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors dropout: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Andrology. 2016 Nov;4:1002–1009. doi: 10.1111/andr.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Boddi V, Castellini G, Casale H, et al. An integrated approach with vardenafil orodispersible tablet and cognitive behavioral sex therapy for treatment of erectile dysfunction: A randomized controlled pilot study. Andrology. 2015;3:909–918. doi: 10.1111/andr.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.McCann B, Knight PK. Changes in sexual inhibition and excitation during PDE5I therapy. Int J Impot Res. 2014;26:146–150. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2013.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Althof SE, O'Leary MP, Cappelleri JC, et al. Impact of erectile dysfunction on confidence, self-esteem and relationship satisfaction after 9 months of sildenafil citrate treatment. J Urol. 2006;176:2132–2137. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Reisman Y, Eardley I, Porst H. New developments in education and training in sexual medicine. J Sex Med. 2013;10:918–923. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wiggins A, Tsambarlis PN, Abdelsayed G, et al. A treatment algorithm for healthy young men with erectile dysfunction. BJU Int. 2019;123:173–179. doi: 10.1111/bju.14458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Capogrosso P, Ventimiglia E, Boeri L. Should we tailor the clinical management of erectile dysfunction according to different ages? J Sex Med. 2019;16:999–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.03.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gott M, Hinchliff S. How important is sex in later life? The views of older people. Soc Sc Med. 2003;56:1617–1628. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Annon JS. The PLISSIT model: A proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioral treatment of sexual problems. J Sex Ed Ther. 1976;1:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Davis S, Taylor B. Elsevier; Edinburgh: 2006. From PLISSIT to ex-PLISSIT. Rehabilitation: The use of theories and models in practice; pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rita B, Ardito RB, Rabellino D. Therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy: Historical excursus, measurements, and prospects for research. Front Psychol. 2011;2:270. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Colson MH, Cuzin B, Faix A, et al. Effective management strategies for patient and couple with erectile dysfunction. Sexologies. 2018;27:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Masters W, Johnson VE. Little, Brown and Company; New York, NY: 1970. Human sexual inadequacy. [Google Scholar]