Abstract

Introduction

Microaggressions are subtle statements or actions that reinforce stereotypes. Medical students, residents, and faculty report experiences of microaggressions, with higher incidences among women and marginalized groups. An educational tool utilizing the acronym VITALS (validate, inquire, take time, assume, leave opportunities, speak up) provided a framework for processing and addressing microaggressions encountered in the academic health center environment.

Methods

We developed a 60-minute workshop designed to raise awareness of microaggressions encountered by medical students and trainees. The workshop consisted of a didactic presentation and multiple interactive exercises shared in small- and large-group formats. Participants also completed pre- and postsurvey instruments to assess changes in their knowledge and attitudes about promoting an environment that prevents microaggressions from occurring.

Results

There were 176 participants who completed our workshop. In comparing anonymized pre- and postworkshop responses submitted by attendees, an increase in recognition of one's own potential stereotypical beliefs about social identity groups was observed. Participants also expressed a greater sense of empowerment to foster mutual respect in health care settings. After completing the workshop, attendees indicated a greater likelihood to engage in difficult conversations, including responding to microaggressions, which both peers and superiors encountered in both academic and clinical environments.

Discussion

The workshop provided an interactive format for medical students and trainees to gain awareness, knowledge, and tools for addressing microaggressions encountered in health care settings.

Keywords: Microaggressions, Bystander, Imposter Syndrome, Communication Skills, Diversity, Inclusion, Health Equity, Anti-racism

Educational Objectives

By the end of this session, participants will be able to:

-

1.

Identify common types of microaggressions that occur within medical education and training.

-

2.

Discuss the hierarchical aspects of the medical profession and how power differentials may affect the responses to microaggressions.

-

3.

Use the VITALS (validate, inquire, take time, assume, leave opportunities, speak up) framework when responding to microaggressions.

Introduction

Microaggressions are subtle statements or actions directed at nondominant groups that reinforce stereotypes and affirm the notion of someone's second-class status in society.1 Dr. Chester Pierce initially coined the term microaggressions in 1970. He recommended looking beyond the “gross and obvious” examples of racism and towards the summative harm of more understated events.2 Though classically ascribed to racially charged events, the understanding of microaggressions has evolved to include gender identity, immigration status, sexual orientation, disability, and other identity groups that have been historically marginalized or made vulnerable.1

There are several subtypes of microaggressions: microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations.1 Microassaults are intentional, overt forms of discrimination. In the medical profession, a microassault might involve a faculty member stating to women residency program applicants that they cannot fully commit to the profession due to their child-rearing responsibilities. Microinsults describe using words and actions to covertly convey insult and/or inferiority. This type of microaggression often happens in an unconscious and unintentional manner (e.g., complimenting a Hispanic/Latinx physician as being a credit to the person's ethnic community). Microinvalidations capture the subtle comments and actions that undermine and/or invalidate the lived experiences, feelings, and thoughts of marginalized individuals. The subtlety of microinvalidations makes them a strikingly insidious form of microaggressions. They frequently go unrecognized when they occur. As an example, an underrepresented in medicine (URiM) medical student may experience disproportionate criticism of presentation skills on rounds. If the student calls attention to this disparate treatment, dismissal of the student's concern without interrogation of the circumstances constitutes a type of microinvalidation. Perpetuation of the microinvalidation occurs when the student then receives a directive to work harder on improving said presentation skills.

Some critics continue to assert that microaggressions exemplify nothing more than harmless statements and that they lack the malicious intent ascribed to them.3,4 However, the reinforcement of superiority in the advantaged group, while exacerbating the daily struggles experienced by minoritized groups, preserves the tolerance of negative bias and mistreatment within an environment.1,5–9 A recent study by Dr. Andre Espaillat and colleagues revealed that 54% of students at a US medical school experienced microaggressions, especially women and URiM students.4 This aligns with Katherine C. Brooks’ description of the silent curriculum as a form of complicit injustices embedded within medical school education.10 Furthermore, microaggressions compound the imposter syndrome phenomenon—one's inability to internalize personal success despite objective evidence of merit. Imposter syndrome can confer crippling anxiety on those who experience it and can induce fear of exposure as a fraud unqualified to occupy the spaces of fellow high achievers.11–13

Many of the individuals who commit microaggressions, as well as bystanders who witness these incidents, repeatedly fail to recognize these actions as egregious. This speaks to how commonplace and normalized microaggressions are within the medical profession, as described both by medical literature and in mainstream media outlets.14,15 The resulting invisibility creates a false sense of credibility for offenders who deny their culpability when challenged about the harmful impact of their behaviors. Too often, this leaves recipients of microaggressions tasked with the responsibility of managing their mistreatment, further compounding the psychological harm for them.16

Members of excluded and marginalized groups have typically developed coping mechanisms for dealing with overt acts of racial abuse. As a more subtle form of racialized mistreatment, however, microaggressions happen at a greater frequency than overt terrorization. Microaggressions also thrive on their invisibility to others within the shared environment. The increasing distress caused by repeated exposure to microaggressions takes a cumulative toll on those experiencing this form of mistreatment.6,9 The concept of racial battle fatigue helps describe this phenomena and has been more formally defined as “the result of constant physiological, psychological, cultural, and emotional coping with racial microaggressions in less-than-ideal and racially hostile or unsupportive environments.”17 For example, just hearing about the struggles of others and how they correlate with a person's own lived experiences can initiate a corresponding stress response cascade.18,19 This chronic state of mental, emotional, and physiological exhaustion engenders increasingly jaded responses to future discriminatory incidents. Individuals then spend an inordinate amount of time wrestling with deciding when addressing an incident supersedes the mental and emotional investment required to do so.9

Among URiM medical students and trainees, microaggressions reinforce stereotypes that they already expend significant mental, physical, and emotional effort to avoid manifesting. Repeatedly experiencing microaggressions also exhausts cognitive functioning and sabotages performance on standardized exams.7 Our workshop was created in response to medical students and graduate medical trainees requesting specific strategies for addressing the range of microaggressions they experienced in both the clinical and academic settings. The development of this activity presented us with an opportunity to further interrogate the culture of silence surrounding microaggressions within academic medicine. Furthermore, it provided a potential tool for faculty to recommend when empowering students to address mistreatment encountered in academic and clinical environments. Although students and trainees served as the primary target audience, the workshop offered tools for responding to microaggressions that other health care students, trainees, and professionals could also use.

Our workshop adds to previous literature addressing microaggressions and mistreatment within the medical profession and health care. Publications by Dr. Emily E. Whitgob and colleagues as well as Dr. Kimani Paul-Emile and colleagues have addressed mistreatment in the clinical environment when patients or their family members serve as the inciting source.20,21 Another framework, ERASE, educates faculty on how to respond and support their students and trainees who experience mistreatment perpetuated by patients in the clinical setting as well.22 While sharing concepts similar to the PEARL framework for medical students published by Dr. Rhonda Graves Acholonu and colleagues and the OWTFD (observe, why, think, feel, desire) framework of Dr. Sylk Sotto-Santiago and colleagues, our program expands on their work by explicitly delineating a wider range of verbal prompts for participants to choose and practice when responding to microaggressions.23,24 Our workshop design integrated requests from students who desired exact verbal prompts to use when they encountered these often frustrating and humiliating situations. Our efforts also sought to acknowledge and accommodate those who reported consistently struggling to react as microaggressions occurred. By normalizing the frequency of this latter scenario, our VITALS (validate, inquire, take time, assume, leave opportunities, speak up) tool incorporated strategies demonstrating ways to address microaggressions after they had happened. Furthermore, our awareness and understanding of the enormous toll carried by targets of microaggressions motivated us to include details concerning the responsibilities of bystanders to act as allies when witnessing microaggressions. From our perspective, actively mobilizing bystanders to address these forms of racialized mistreatment served as an additional catalyst and mechanism for maintaining more equitable and inclusive environments.

Methods

We originally developed the Interrupting Microaggressions workshop and VITALS tool (Appendix A) in 2016 based on our inability to identify a concise, user-friendly, widely used tool for responding to microaggressions encountered in the medical setting. We utilized peer-reviewed social sciences literature and incorporated anecdotal accounts of practicing physicians’ responses to incidents of mistreatment in their professional environment to inform our development.21,25 Dr. Diane J. Goodman's book Promoting Diversity and Social Justice: Educating People From Privileged Groups provided us with key themes such as: (1) paraphrasing, (2) seeking clarification, and (3) separation of intent from impact, that we built into the framework of the workshop's curricular content and VITALS tool.26 We also incorporated feedback we received from other educators familiar with training on microaggressions to finalize the tool.

We then designed the workshop as a vehicle to explore the topic of microaggressions and introduce the tool as an easily remembered and concise response for taking action. The 60-minute workshop had a two-part presentation format: (1) a short and interactive large-group didactic session via PowerPoint presentation (Appendix B) and (2) small-group sessions where participants shared past experiences with microaggressions, later followed by discussions that encouraged practicing the use of the VITALS tool (Appendix A) to readdress their prior experiences.

The PowerPoint (Appendix B) started by establishing ground rules for the session. It also explained why creating a brave space environment (Appendix C) was needed to ensure everyone felt comfortable authentically participating and expressing themselves without fear or worry of being attacked, ridiculed, or denied validation of their experiences.27 Additionally, the PowerPoint defined microaggressions, emphasized the distinction between intent versus impact of behaviors associated with microagressions, and described the role of bystanders to interrupt incidents they might witness.

The small-group discussion had attendees share their prior experiences with microaggressions and how they handled them. Limiting the number of participants to five per group fostered a more intimate conversation among peers. We intentionally avoided placing a faculty facilitator within the small groups due to concerns for inequitably shifting a group's power dynamics and stymying attendee participation. After we introduced the VITALS tool (Appendix A), the same small groups came back together so that attendees could practice generating reimagined, simulated responses to the prior experiences they had shared.

We initially presented the Interrupting Microaggressions workshop to medical students. Later, we separately provided the workshop without modification to pediatric trainees. The workshop setting required a location with audio and video capabilities. It was also important to utilize a space where attendees participated in large-group discussions led by the facilitator as well as assembled into small groups for self-directed discussions.

Essential prerequisites for facilitators were proficiency in skills such as consensus building and conflict resolution within small- and large-group settings. We made the facilitator guide (Appendix D) for the workshop available to the faculty and/or staff identified as facilitators prior to the session. Otherwise, no additional facilitator training was done. Of note, in addition to the essential prerequisites, a preferred prerequisite skill was agility in facilitating discussions of structural racism, racialized forms of microaggressions, and the role of medicine and science in justifying the use of race to uphold long-standing racist practices.

Workshop participants were asked to complete pre- and postworkshop surveys (Appendices E and F, respectively) immediately before and after delivery of the workshop. A search of the medical literature at the initiation of this process did not produce a validated survey tool to evaluate attitudes and comfort level with attributes essential to understanding microaggressions. In addition to addressing likelihood and comfort level with confronting microaggressions, we believed gaining insight into how the workshop altered participants’ perceptions of personal bias and their comfort communicating across social identity groups warranted examination. Conceding the inability to match the anonymized pre- and postsurveys to their respective participants, we analyzed the responses received using chi-squares and Cochran-Armitage trend tests.

The study was determined to be exempt from review by the University of California, Los Angeles, Institutional Review Board.

Results

The 176 workshop participants yielded response rates on the pre- and postsurveys of 100% and 93%, respectively. The composition of workshop participants included 23 pediatric trainees and 153 medical students. To maintain anonymity, we did not collect gender, racial and ethnic identity, or any other additional demographic data.

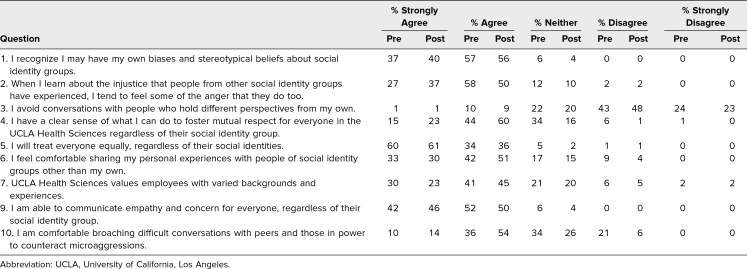

Based on presurvey responses, participants came into the workshop with a high level of agreement in several areas that pertained to self-awareness concerning their attitudes about others from differing social identities (see Table 1). Ninety-four percent of participants either strongly agreed or agreed that they could recognize their own biases and stereotypical beliefs (question 1). When asked about treating everyone equally, 94% affirmed that they engaged in equal treatment of others (question 5). In considering their level of comfort sharing personal experiences with people of differing social identities from their own, 75% felt capable of doing so (question 6). When queried about their ability to communicate empathy and concern for others who differed from them, 94% described themselves as capable (question 9).

Table 1. Self-Reported Agreement by Participants Pre- and Postintervention (N = 176).

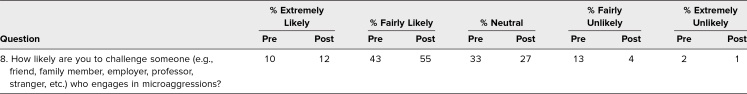

Regarding comfort with initiating difficult conversations to counteract microaggressions committed by their peers or those in power (question 10), 46% of participants either strongly agreed or agreed about their ability to do so in the presurvey responses. After the workshop, this improved to 68% (p < .001). A similar increase was seen when participants were queried as to how likely they were to challenge someone engaging in a microaggression (question 8; Table 2). Presurvey results found 53% rating themselves as extremely likely or fairly likely to say something, which increased to 67% on the postsurvey assessments (p = .005). We also asked participants about their perceptions regarding what they could realistically do to decrease the incidence of microaggressions. The response to the item “Fostering an environment that expected mutual respect for others, irrespective of differences in social identities,” significantly increased from 59% presurvey to 82% postsurvey (p < .001).

Table 2. Self-Reported Likelihood of Participants Pre- and Postintervention (N = 176).

Discussion

Taught through the Interrupting Microaggressions workship, the VITALS tool adds a new framework to the medical literature for navigating microaggressions. Besides providing ways to address microaggressions at the time that they occur, the VITALS tool also considers options for revisiting these incidents at a time distant from the inciting event. The interactive nature of the workshop enables participants to share highly relatable and pertinent examples of microaggressions with their peers. These examples typically encompass incidents that have happened to participants in their current academic and clinical medical environments. The anecdotes shared assist in generating awareness and understanding around the detrimental issues that microaggressions exacerbate within and beyond academic medicine.

Presenting this workshop to (1) newly matriculating medical students, (2) medical students transitioning to their third-year clerkship rotations, and (3) graduate medical trainees at differing stages within their residency program demonstrated its generalizability across a broad range of learners. Additionally, it helped capture perspectives on microaggressions from multiple points throughout the medical education continuum. Through specific prompts, attendees participated in facilitated discussions and shared details about incidents where they perceived themselves as perpetrators, targets, or bystanders. This provided opportunities for participants to invest in thinking critically about both their previous and future responses to microaggressions in a more germane manner than asking them to opine on hypothetical or adapted case vignettes.

Given our inability to identify validated survey instruments that assessed directly observed skills in responding to microaggressions at the time of our tool's creation in 2016, we relied on survey questions that interrogated the attitudes and self-perceived knowledge we believed essential to employing the strategies introduced by our workshop. The emphasis on anonymous evaluations of this program created limitations to our ability to interpret the data we obtained. The lack of demographic data about our survey participants precluded us from stratifying our results based on stage of education or training. Similarly, the lack of demographic details prevented a more granular assessment of which participants demonstrated the most robust changes after participating in our workshop. Another challenge we experienced involved the need to extinguish robust conversations among peers in both the small-group and larger-group settings to comply with the 60-minute time allotment. To optimize effectiveness and increase time for participants to practice acquisition of skills, we recommend 75–90 minutes for this workshop.

We appreciated the specific feedback that some participants shared with us concerning the VITALS tool. Their critique focused on concerns that our initial “A”—representing “assume the best of each other”—in VITALS overly simplified or even excused more egregious microassaults and other forms of mistreatment. In response, we talked through the value of ascribing positive intent to people while requiring accountability for their actions, particularly when intent was unknown. Because of those discussions, we updated our phrasing to “assume the best of each other and assume the need for clarity.” We felt this captured the critique offered by some attendees and strengthened our exhortation to separate an offender's intention from the harmful impact of the action. This inclusion of both assumptions deliberately asks participants to pursue clarifying information, particularly if dealing with an emotionally charged situation. Otherwise, we have been fortunate to facilitate an extraordinarily well-received workshop now updated to reflect this slight modification of the VITALS tool.

Our workshop accomplished the execution of an interactive educational session on microaggressions. Participants learned an easily remembered tool for responding to microaggressions whether as a target or a bystander. Specifically, our tool addressed incidents occurring in the wide range of environments that our learners experienced as a result of their positionality within an institution's academic medical center.

In considering future directions for this workshop, we suggest expanding the time allotment to 90 minutes. Based on the ease of executing this program across differing groups of participants, we recommend the use of this workshop with participants at any stage of medical training or practice. Recognizing the increased demand for virtual options, the workshop's design also permits conversion to an online workshop format. This simply requires utilizing a platform that supports videoconferencing and creation of breakout rooms.

A 90-minute workshop offers added flexibility for users to insert new content into our existing curriculum. One option might introduce a segment where participants review a case vignette and then compare and contrast how those with differing experiences of microaggressions utilize the VITALS tool. Another option could ask participants to identify specific ways for perpetrators to practice rectifying the harms caused by the microaggressions they commit. For more advanced learners, we suggest adding discussion prompts that challenge participants to use the VITALS tool in advocating for system-level interventions that mitigate microaggressions and their harms to the learning environment. Given the numerous challenges that remain with eradicating the problems posed by microaggressions that occur in the health care setting, we recommend pursuing future studies aimed at delineating which groups of participants benefit most from this workshop's structure.

Appendices

- VITALS Tool Handout.docx

- Slide Presentation.pptx

- Brave Space Handout.pdf

- Facilitator Guide.docx

- Microaggressions Presurvey.docx

- Microaggressions Postsurvey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

None to report.

Prior Presentations

Hodges L. VITALS for interrupting microaggressions. Oral presentation at: National Medical Association Annual Convention and Scientific Assembly; July 27–31, 2019; Honolulu, HI.

Ethical Approval

The University of California, Los Angeles, Institutional Review Board deemed further review of this project not necessary.

References

- 1.Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):271–286. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solórzano D, Ceja M, Yosso T. Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: the experiences of African American college students. J Negro Educ. 2000;69(1–2):60–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lilienfeld SO. Microaggressions: strong claims, inadequate evidence. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2017;12(1):138–169. 10.1177/1745691616659391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espaillat A, Panna DK, Goede DL, Gurka MJ, Novak MA, Zaidi Z. An exploratory study on microaggressions in medical school: what are they and why should we care? Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(3):143–151. 10.1007/s40037-019-0516-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sue DW. Microaggressions and “evidence”: empirical or experiential reality? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2017;12(1):170–172. 10.1177/1745691616664437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salvatore J, Shelton JN. Cognitive costs of exposure to racial prejudice. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(9):810–815. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01984.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(5):797–811. 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams DR, Williams-Morris R. Racism and mental health: the African American experience. Ethn Health. 2000;5(3-4):243–268. 10.1080/713667453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter RL. An Examination of Workplace Racial Microaggressions and Their Effect on Employee Performance. Master's thesis. Gonzaga University; 2011. Accessed September 15, 2021. https://search.proquest.com/openview/be9ac54fc1e8e009feec949acd845b1d/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y&casa_token=FsG0eAyOsjIAAAAA:Mf5-Ca_YzaJ0i1s-RMb6_bGV1yywSo_c6MCPmzPHWaHHgyPITPgXtZb0aGDqRhckUJ21iEF5wQI [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks KC. A silent curriculum. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1909–1910. 10.1001/jama.2015.1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cozzarelli C, Major B. Exploring the validity of the impostor phenomenon. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1990;9(4):401–417. 10.1521/jscp.1990.9.4.401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villwock JA, Sobin LB, Koester LA, Harris TM. Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:364–369. 10.5116/ijme.5801.eac4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peteet BJ, Montgomery L, Weekes JC. Predictors of imposter phenomenon among talented ethnic minority undergraduate students. J Negro Educ. 2015;84(2):175–186. 10.7709/jnegroeducation.84.2.0175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molina MF, Landry AI, Chary AN, Burnett-Bowie SAM. Addressing the elephant in the room: microaggressions in medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(4):387–391. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg E. For doctors of color, microaggressions are all too familiar. New York Times. August 11, 2020. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/11/health/microaggression-medicine-doctors.html

- 16.Shelton JN, Richeson JA, Salvatore J, Hill DM. Silence is not golden: the intrapersonal consequences of not confronting prejudice. In: Levin S, van Laar C, eds. Stigma and Group Inequality: Social Psychological Perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006:65–82. 10.4324/9781410617057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith WA, Allen WR, Danley LL. “Assume the position … you fit the description”: psychosocial experiences and racial battle fatigue among African American male college students. Am Behav Sci. 2007;51(4):551–578. 10.1177/0002764207307742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith WA, Hung M, Franklin JD. Racial battle fatigue and the miseducation of Black men: racial microaggressions, societal problems, and environmental stress. J Negro Educ. 2011;80(1):63–82. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franklin JD. Coping with racial battle fatigue: differences and similarities for African American and Mexican American college students. Race Ethn Educ. 2019;22(5):589–609. 10.1080/13613324.2019.1579178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitgob EE, Blankenburg RL, Bogetz AL. The discriminatory patient and family: strategies to address discrimination towards trainees. Acad Med. 2016;91(11)(suppl):S64–S69. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul-Emile K, Smith AK, Lo B, Fernández A. Dealing with racist patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(8):708–711. 10.1056/NEJMp1514939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkins KM, Goldenberg MN, Cyrus KD. ERASE-ing patient mistreatment of trainees: faculty workshop. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10865. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acholonu RG, Cook TE, Roswell RO, Greene RE. Interrupting microaggressions in health care settings: a guide for teaching medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10969. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sotto-Santiago S, Mac J, Duncan F, Smith J. “I didn't know what to say”: responding to racism, discrimination, and microaggressions with the OWTFD approach. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10971. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds KL, Cowden JD, Brosco JP, Lantos JD. When a family requests a White doctor. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):381–386. 10.1542/peds.2014-2092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodman DJ. Promoting Diversity and Social Justice: Educating People From Privileged Groups. Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali D. Safe Spaces and Brave Spaces: Historical Context and Recommendations for Student Affairs Professionals. National Association of Student Personnel Administrators; 2017. NASPA Policy and Practice Series no. 2. Accessed September 15, 2021. https://www.naspa.org/images/uploads/main/Policy_and_Practice_No_2_Safe_Brave_Spaces.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- VITALS Tool Handout.docx

- Slide Presentation.pptx

- Brave Space Handout.pdf

- Facilitator Guide.docx

- Microaggressions Presurvey.docx

- Microaggressions Postsurvey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.