Abstract

Background

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy refers to the structural and functional changes in the heart leading to either impaired systolic, diastolic, electrocardiographic, and neurohormonal changes associated with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy is present in 50% of patients with cirrhosis and is clinically seen as impaired contractility, diastolic dysfunction, hyperdynamic circulation, and electromechanical desynchrony such as QT prolongation. In this review, we will discuss the cardiac physiology principles underlying cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, imaging techniques such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and scintigraphy, cardiac biomarkers, and newer echocardiographic techniques such as tissue Doppler imaging and speckle tracking, and emerging treatments to improve outcomes.

Methods

We reviewed available literature from MEDLINE for randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and real-world outcomes using the search terms “cirrhotic cardiomyopathy,” “left ventricular diastolic dysfunction,” “heart failure in cirrhosis,” “liver transplantation,” and “coronary artery disease”.

Results

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy is associated with increased risk of complications such as hepatorenal syndrome, refractory ascites, impaired response to stressors including sepsis, bleeding or transplantation, poor health-related quality of life and increased morbidity and mortality. The evaluation of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy should also guide the feasibility of procedures such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, dose titration protocol of betablockers, and liver transplantation. The use of targeted heart rate reduction is of interest to improve cardiac filling and improve the cardiac output using repurposed heart failure drugs such as ivabradine. Liver transplantation may also reverse the cirrhotic cardiomyopathy; however, careful cardiac evaluation is necessary to rule out coronary artery disease and improve cardiac outcomes in the perioperative period.

Conclusion

More data are needed on the new diagnostic criteria, molecular and biochemical changes, and repurposed drugs in cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. The use of advanced imaging techniques should be incorporated in clinical practice.

Keywords: cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, beta blocker, hemodynamics in cirrhosis

Abbreviations: 2-AG, 2-arachidonylglycerol; 2D, two-dimensional; AEA, Anandamide; ANP, Atrial Natriuretic Peptide; ASE, the American Society of Echocardiography; AUC, area under the curve; BA, bile acid; BNP, Brain natriuretic peptide; CAD, coronary artery disease; CB-1, cannabinoid −1; CCM, Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy; CMR, cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging; CO, cardiac output; CVP, central venous pressure; CT, computed tomography; CTP, Child–Turcotte–Pugh; DT, deceleration Time; ECG, electrocardiogram; ECV, extracellular volume; EF, Ejection fraction; EMD, electromechanical desynchrony; ESLD, end-stage liver disease; FXR, Farnesoid X receptor; GI, gastrointestinal; GLS, Global Longitudinal strain; HCN, Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide–gated; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; HF, heart failure; HfrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HfmrEF, heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction; HO, Heme oxygenase; HPS, hepatopulmonary syndrome; HR, heart rate; HRS, hepatorenal syndrome; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; IVC, Inferior Vena Cava; IVCD, IVC Diameter; IVS, intravascular volume status; LA, left atrium; LAVI, LA volume index; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; L-NAME, NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; LT, liver transplant; LV, left ventricle; LVDD, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; LVEDV, LV end diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, LV end systolic volume; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; MR, mitral regurgitation; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; MV, mitral valve; NAFLD, Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, Nitric oxide synthases; NTProBNP, N-terminal proBNP; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedged pressure; PHT, portal hypertension; PWD, Pulsed-wave Doppler; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; SA, sinoatrial; SD, standard deviation; SV, stroke volume; SVR, Systemic vascular resistance; TDI, tissue Doppler imaging; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; TR, Tricuspid valve; TRPV1, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; VTI, velocity time integral; USG, ultrasonography

Introduction

Cirrhosis and portal hypertension is associated with the development of a hyperdynamic circulation and complications.1 including development of ascites, variceal bleeding, acute and chronic kidney injury, and susceptibility to infections such as bacterial peritonitis. A frequently unreported complication related to cirrhosis is cirrhotic cardiomyopathy (CCM) which is present in 30–70% of patients in various series.2

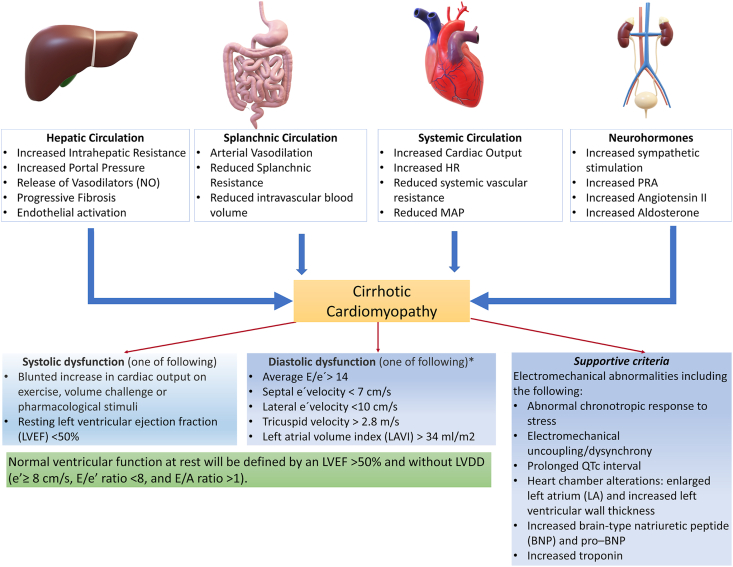

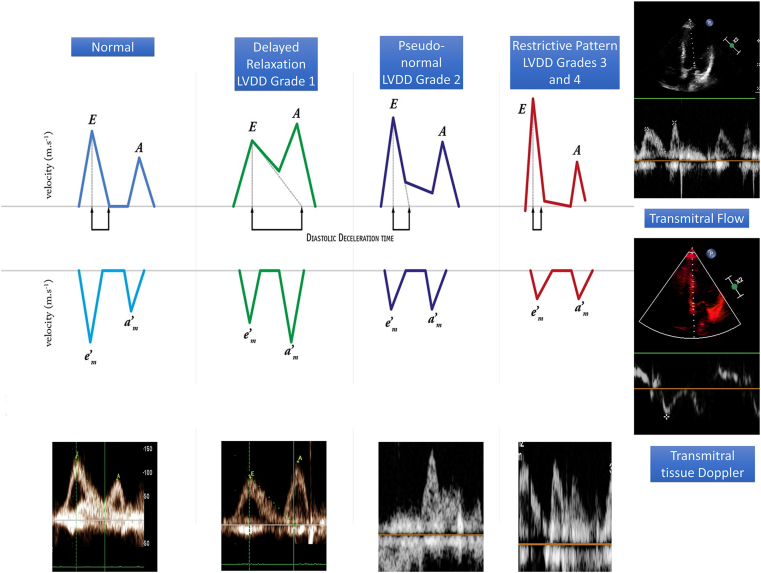

The World Conference of Gastroenterology in 2005 defined CCM as cardiac dysfunction characterized by diastolic dysfunction, systolic dysfunction, or impaired systolic response to stress and abnormalities in electrophysiological responses in absence of underlying primary cardiac disease.3,4 The diagnosis of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (LVDD) is as per the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) guidelines.5 Figure 1 shows the mechanisms leading to the development of CCM and diagnostic criteria for CCM and LVDD.5 The transmitral inflow peak early velocity (E), the late atrial-dependent filling velocity (A), early septal mitral annular diastolic velocity (e’), left atrial volume index (LAVI), the E-to-A wave ratio, deceleration time (DT), and isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT).5 The echocardiographic changes have been described as a decline in E/A ratio or rise in E/e’ ratio. Figure 2 shows the measurement criteria for these parameters on transmitral Doppler and TDI.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic criteria and pathophysiological mechanisms of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy.

Figure 2.

Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (LVDD) using tissue Doppler imaging. E: transmitral flow velocity during early ventricular filling; A, transmitral flow velocity during atrial contraction; e’ Tissue Doppler velocity at the mitral annulus during early ventricular filling.

The pathophysiology of CCM is independent of the underlying etiology of liver cirrhosis.6 Numerous studies have revealed that the hyperdynamic circulation, high sympathetic adrenergic activity, and the presence of arteriovenous communications contribute to the increased cardiac output. These pathophysiological conditions result in modification in cardiac structure, atrial and ventricular diameters, and volumes and pumping capacity.7,8 Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy is often asymptomatic and is unmasked in periods of stress, such as sepsis, surgery, or critical illness. The clinical presentation includes fluid retention, dyspnea, and reduced exercise capacity.9 Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy has been observed as a key factor in the progress of other diseases such as hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) and relative adrenal insufficiency.10,11 With the easy availability of advanced cardiac imaging, the use of updated criteria for diagnosis as proposed by Izzy et al. is gaining interest.12 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Updated Criteria for Diagnosis of Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy (CCM).12

| Systolic Dysfunction | Advanced Diastolic Dysfunction | Future Research Needing Validation in CCM |

|---|---|---|

| Any of the following | ≥3 of the following | Electrocardiographic changes |

| LVEF ≤50% | Septal e’ velocity <7 cm/s | Electromechanical dissociation |

| Absolute Global Longitudinal strain (GLS) <18% or >22% | E/e’ ratio≥ 15 | Changes in myocardial mass and chamber volumes |

| LAVI >34 mL/m2 | Serum biomarkers | |

| TR velocity >2.8 m/s | MR imaging | |

| Extracellular water and fibrosis |

Abbreviations: CCM, cirrhotic cardiomyopathy; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; LAVI, left atrium volume index; MR, magnetic resonance.

Pathophysiology of cardiovascular dysfunction in cirrhosis

The cirrhotic heart has been subject to much investigation. Right-sided heart failure contributes to congestive hepatopathy. Severe sepsis, cardiogenic shock, or left heart circulatory failure in acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) results in hypoxic liver injury. Conversely, the presence of portal hypertension itself results in cardiomyopathy because of remodeling of the heart to cope with the cirrhosis-related systemic vasodilation. This situation can be termed a “hepato-cardiac syndrome” akin to the “hepatorenal” (HRS) and hepatopulmonary syndromes (HPS). The development of cirrhosis leads to altered lipid metabolism, detoxification of drugs, ethanol, and hormones. Impaired degradation of vasoactive substances such as adrenaline and noradrenaline, atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), glucagon, renin, substance P, aldosterone, vasopressin, and so on results in these neurohormones bypassing the liver and entering the systemic circulation through portosystemic collaterals. Compromised hepatic excretion results in efflux of high levels of bile acids and bilirubin in the systemic circulation, which impact sinus rhythm, suppress myocardial activity, and give rise to arrhythmia. The expression of Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) in the liver, kidney, intestine, and adrenal glands controls the metabolism of cholesterol, lipids, and bile acids. FXR is also localized in the heart, vasculature, and adipose tissue, where it can contribute to myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury as an apoptosis mediator.13 The cardiomyocytes and smooth muscle cells are known to express FXR, and, therefore, the high levels of bile acids in chronic cholestasis affect cardiovascular signaling pathways, a condition aptly termed ‘cholecardia’. Furthermore, bile acids reduce the affinity and density of beta-adrenoceptors and modification in the cardiac plasma membrane.14

The role of bile acids (BAs) in CCM is supported by several facts. Firstly, the levels of BAs, which are signaling molecules and affect the FXR pathway, are usually >30–40 μmol/l in cirrhosis, as opposed to the 2–15 μmol/l in apparently healthy individuals. Secondly, BAs can also regulate nuclear receptors (vitamin D receptor, pregnane-X receptor), G-protein coupled receptors (TGR5, muscarinic receptors), α5β1 integrins, and calcium-activated potassium channels. The cardiomyocyte membrane is affected by Na/Ca entry, and when reduced by the BA mediated K efflux due to the opening of large Ca2+-dependent K conductance channels, result in reduced contractility, predisposition to arrhythmias and decreased chronotropic effect.14 The FXR ligands can inhibit IL-1β-mediated inflammation in a rat model of aortic smooth muscle cells. This is mediated by nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) endotoxemia increases activity of NF-κB–endocannabinoid–NF α pathway, which reduces cardiac contractility in animal models. The VDR also regulates calcium influx into the cardiomyocyte, which affects diastolic function. Bile acids also increase the activity of calcium-activated potassium channels, which is associated with the systemic vasodilation due to the relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells.15,16 Bile acids can also act via reduction in endothelin-1 expression, modulation of inducible and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Thus BAs, via FXR and other pathways, affect the metabolism and function of cardiomyocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells.17

Hemodynamic homeostasis in cirrhosis

The decrease in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and redistribution of blood volume with reduced intravascular volume compartment and third space fluid losses. Systemic vasodilatation is compensated by an increase in cardiac output (CO) in the initial stages of compensated cirrhosis. However, as the stage of liver cirrhosis progresses to decompensation, more prominent arterial vasodilatation and reduced SVR leads to a fall in CO. Thus, the cardiac homeostat is reset in a cirrhotic hyperdynamic circulation, wherein an increased heart rate, and, therefore, increased cardiac output will no longer be able to compensate for the reduced mean arterial pressure (MAP) and decreased blood volumes in central venous territories.18 Consequent activation of vasoconstrictor systems including renin-angiotensin-aldosterone, vasopressin, and the sympathetic nervous system comes into play to maintain the intravascular blood volume and pressure. These compensatory pathways cause an increase in sodium and water retention, refractory ascites, and HRS. In critically ill patients with cirrhosis, the limited cardiac reserve is further stressed; CCM and heart failure may be diagnosed for the first time when the patient develops sepsis or septic shock.19

Because of the increase in intestinal permeability by altered microbiota, and bacterial translocation, cirrhosis induces an impaired immune response which results in the release of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukins (IL-6 and IL-8), and nitric oxide (NO). This state of systemic inflammation leads to circulatory dysfunction followed by multiorgan failure. The cirrhotic heart also responds to systemic inflammation by remodeling.20,21 This state of systemic inflammation contributes to circulatory dysfunction in sepsis followed by multiorgan failure.12,22, 23, 24 The association of CCM and failure to increase cardiac output in response to stressors such as sepsis, exercise, drugs such as dobutamine, and surgery.25

Signaling pathways in cirrhotic cardiomyopathy

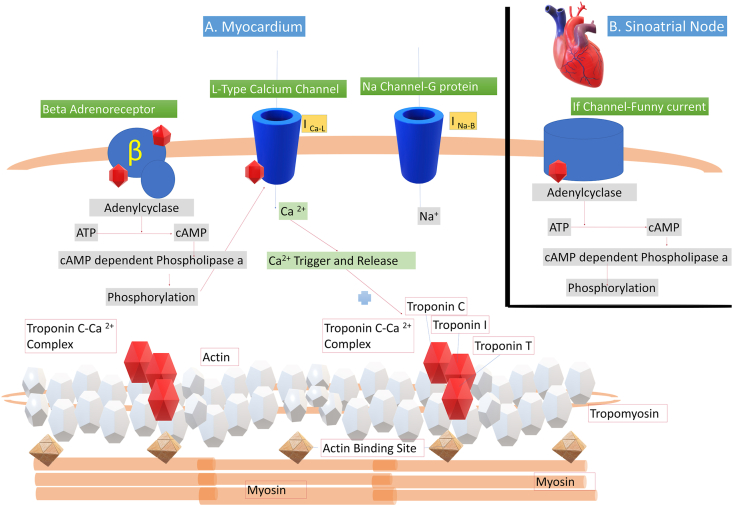

Molecular mechanisms for increased cardiac stiffness and filling pressures in LVDD include impaired calcium channels, abrogated beta-adrenergic receptor system, and accumulation of cytokines. The pathophysiology involves defects in cardiac beta-adrenergic receptor signaling, vasodepressant effects of nitric oxide, and carbon monoxide increased endocannabinoids (anandamide) and myocyte apoptosis. The changes in the cardiomyocyte include changes in the plasma membrane, and calcium-ion channels that lead to abnormal cardiomyocyte membrane receptors, including downregulation of the beta-adrenergic system. Negative–inotropic pathways are activated, caused by inflammatory stimuli, including NO, CO, endocannabinoids, and cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α. These result in cardiomyocyte apoptosis and a shift inmyosin heavy chain isoform from the powerful a-subtype to the weak b-isoform. Figure 3 shows the ion channels and signaling pathways in the cirrhotic heart.26

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the molecular events in the cardiac myocyte. Panel A: Channels and signaling pathways in the myocardium: β1-Adrenergic receptor stimulation leads to interaction with G protein; then, a cascade of events from adenylyl cyclase activation leads to the phosphorylation of ion channels. Phosphorylation of the Ca channels ultimately leads to cross-bridging of myosin and actin and, therefore, myocyte contraction. The myosin heavy chain is linked to actin after activation of the troponin I, T and C complex after the influx of Ca 2+. Phosphorylation of Na channels favors depolarization of phase 4 of the action potential, ultimately leading to heart rate acceleration. Several receptor and channel abnormalities have been described in cirrhosis, that account for reduced contractility, chronotropic incompetence, and electromechanical uncoupling. Inset Panel B: Cardiac pacemaker current (If), a mixed sodium-potassium inward current that controls the spontaneous diastolic depolarization in the sinoatrial (SA) node and hence regulates the heart rate. β, β 1-adrenergic receptor; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; G, G protein; I Ca-L, slowly decaying inward Ca2-L current; INa–B, inward Na background leak current.

Diagnosis of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy appears independent of the underlying etiology of liver disease. The term CCM includes diastolic dysfunction, undermined systolic response to external stress and electrophysiological abnormalities such as prolonged QTC interval.4,27 Systolic heart dysfunction is defined as a reduction in ejection fraction (EF) < 55% with an enlargement in end-diastolic chamber volume whereas diastolic dysfunction denotes impaired relaxation of the myocardium causing the increase in the filling pressure of ventricles secondary to increased resistance to filling. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction is diagnosed using tissue Doppler mitral valve velocity measurements. We use tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) which quantifies different indices that change with diastolic dysfunction. An E/e’ integral value more than 14, septal and lateral e’ velocity integral value less than 7 cm/s and 10 cm/s, respectively, along with tricuspid velocity more than 2.8 m/s. The supporting criteria for diagnosis of LVDD are changes in cardiac chamber sizes, electrophysiological abnormalities, increased biomarkers such as ANP, N terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-Pro BNP), and troponin I.27, 28, 29, 30

Systolic Dysfunction

In patients with CCM, systolic dysfunction is seen as increased cardiac output with induced stress such as exercise, or on pharmacological stimulation with drugs such as dobutamine, or seen as reduced ejection fraction (<55%) of a resting left ventricle. Wong et al. showed the impaired response of the cirrhotic heart to increase the LVEF on exercise.31 There is a poor ventricular capacitance or increased filling pressure causing low LVEF and cardiac stroke index on exercise.31 Vasoconstrictors such as vasopressin, dobutamine and so on can precipitate latent cardiac dysfunction, decrease ejection fraction, and increase end-diastolic pressure and volume.32,33 Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy also leads to other complications such as inappropriate sinus tachycardia, QTc prolongation, predisposition to arrhythmia, lower myocardium capacity, and excessive wasting of skeletal muscles. In recent times, new techniques such as tissue doppler imaging (TDI) and speckle tracking echocardiography have been used to diagnose systolic dysfunction by measuring abnormal peak value of systolic tissue velocity and strain rate at resting position.34 Heart failure (HF) can be classified into one of three types, HF with preserved EF (HFpEF), HF with reduced EF (HFrEF) and HF with mid-range EF (HfmrEF), based on quantification of the EF as >50%, <40%, and >40% but <50%, respectively.35 The inability of the cirrhotic heart to bear increased ventricular filling pressures and limited cardiac reserve can precipitate HF. In addition, the compensation for effective arterial hypovolemia can no longer be provided by a low CO state, which explains development of HRS as a part of the hepato–cardio–renal axis dysfunction.36, 37, 38

Diastolic Dysfunction

Diastolic dysfunction is defined as increased cardiac stiffness owing to increase in left ventricle end-diastolic pressure.39 The pathological changes which occur during the progression of diastolic dysfunction in the cirrhotic state are the growth of the myocardial mass, fibrosis, and subendothelial oedema which leads to variation in collagen composition and ECV of the myocardium.36,40, 41, 42 In view of functional variation, these pathological changes can be seen as a decrease in myocardium relaxation resulting in abnormal filling patterns such as a shift toward more filling at end systole, increased LA pressure due to delayed transmitral blood flow, and an increase in diastolic pressures, particularly LVEDP. Diastolic dysfunction is much more prevalent than systolic dysfunction, and the latter is rarely present in isolation.27,36,42,43 The grade of LVDD has been shown to be proportional to stage of cirrhosis, with higher prevalence at higher MELD confirming a common causation.36,44, 45, 46 The grade of LVDD is also proportional to impaired health-related quality of life, HRS, refractory ascites and inversely associated with survival.44 In LVDD, enlargement of left atrium occurs due to less compliant LV with increased LV filling pressures and the LAVI exceeds its value above 34 ml/m2.47, 48, 49

Pathological changes in the cirrhotic heart

Patients with CCM have increased heart weight, dilated cardiac chambers, septal and ventricular hypertrophy as well as other structural changes including cardiomyocyte edema and fibrosis, nuclear vacuolation, and pigmentation,41 cell edema, and fibrosis.4 Lunseth et al found delicate diffuse myocardial fibrosis (DMF) in an autopsy study. They described that the interposition of delicate fibrous tissues was frequently noted in the gap caused by transversely ruptured muscle fibers.50

These biophysical and biochemical abnormalities appear independent of the underlying liver cirrhosis etiology. More recently the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) explains the relation of increase in myocardial extracellular volume (ECV) and cardiac function, circulatory fibrosis markers, and disease prognosis. In addition, the excessive ECV of the myocardium has been shown to be associated with inflammation, liver disease progression, and survival rate.51

Increased ECV is a reversible component of CCM and can respond to improvement in liver function after withdrawal of alcohol, or liver transplantation. Magnetic resonance imaging showing extensive myocardial fibrosis suggests that cardiac remodeling is unlikely even after transplantation, suggesting an irreversible component to CCM.

Metabolic syndrome and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy

With the rise of the metabolic syndrome, there is an increased evidence of significant and symptomatic or asymptomatic coronary artery disease (CAD). Therefore, all patients with CCM also need evaluation for associated CAD. Wehmeyer et al demonstrated prevalence of high-grade coronary sclerosis in comparison to control patients.7 Danielsen et al found increased coronary artery calcium score compared with adjusted reference values on cardiac computed tomographic (CT) imaging. The coronary artery calcium score in ethanol-related cirrhosis was significantly higher than in non-alcohol–related cirrhosis and was associated with diastolic dysfunction. These results show that coronary artery lesions are more common in alcoholic cirrhosis than previously anticipated. The differentiation between primary CCM and ischemic cardiomyopathy requires evaluation for coronary artery disease such as angiography or metabolic imaging. Preserved right ventricular function also points to an ischemic cardiomyopathy. The right ventricular/left ventricular end diastolic ratio is lower in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Practically, these two diseases can co-exist and require a combined approach to management.52

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy is independent of etiology, and all patients should be assessed for this under diagnosed complication of liver disease. The presence of metabolic syndrome, use of alcohol and cirrhosis can contribute synergistically as risk factors for clinically undiagnosed case of CCM.

In a nutshell, the cirrhotic heart displays a variation of structure and size, atherosclerotic lesions, and myocardium hypertrophy with impaired functioning, with fibrosis and remodeling in late stages.

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy and trans-jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

The effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) on hemodynamics and relative sensibility of diastolic dysfunction demonstrate improvement in cardiac performance.53 The volume changes which stipulate the inappropriate adaption of the cirrhotic liver to increased preload include enlargement of the left atrium and increase in pulmonary capillary wedged pressure, reflecting poor response in improvement after TIPS insertion in patients with LVDD.54 A simple two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography with TDI and 12 lead electrocardiography should be part of the routine evaluation before a TIPS is inserted. Presence of LVDD ≥ grade 2 and reversal of the E/A ratio predicts the possibility of post TIPS heart failure and mortality. Therefore, cardiac assessment and volume management is essential to maintain systemic hemodynamics in patients who undergo TIPS.54, 55, 56 One study has shown normalization of functions after a few months after the TIPS insertion albeit with persistent mild left ventricular hypertrophy.55 Up to 12% of patients develop heart failure after TIPS.56 Merli M. et al reported normalization of cardiac pressure over time.57

Liver transplantation and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy affects the pre- , peri- , and post-operative stages of liver transplantation.4 As a part of liver transplantation assessment, functional cardiac evaluation is an essential procedure.30 Pre-transplant cardiac assessment includes workup for coronary artery disease, hepatopulmonary syndrome, and porto-pulmonary hypertension. The preoperative cardiovascular tests for a LT candidate include a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and 2D echocardiography. The parameters which should be determined using 2D echocardiography before liver transplantation are left ventricular dimensions, ejection fraction, Doppler velocities, valvular function, and pulmonary artery pressure. The agitated saline bubble contrast helps in the detection of hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS).58 Coronary angiography should be used for CAD screening for the patients with decreased ejection fraction, age more than 50 years, strong CAD-related family history, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, and hyperlipidemia.59 Transplant anesthetists mainly rely on invasive blood pressure monitoring, or integrated hemodynamic devices which use a mathematical algorithm to provide beat to beat data on cardiac output (CO), stroke volume variation (SVV), and so on. However, in patients with a clamped vena cava and a functional bypass, or those who are on high pressor support, these algorithms are not predictive of real intravascular status. Hence the use of transesophageal echocardiography is an excellent asset in the anesthetists’ toolbelt to manage these cases.60

After liver transplantation, the cirrhotic hyperdynamic circulation may continue for 6–9 months. The immediate period of 3–4 months after liver transplantation seems to worsen LVDD and risk of overt HFpEF. Later the diastolic dysfunction improves.61, 62, 63 Cardiac function improves about 6–12 months after the liver transplantation and with improved stress tolerance, cardiac output, and myocardial function.63 Remodeling occurs in the reversible elements of CCM after transplantation with restoration of the portal hypertensive changes in the systemic and splanchnic beds, changes in preload and afterload, and improvement of myocardial ECV. Table 2 indicates the major studies conducted to assess changes in echocardiographic variables in post-transplant patients with documented improvement in echocardiographic variables.62,64, 65, 66, 67 Liver transplantation itself poses a big challenge in surgical procedures in terms of survival rate and the development of life-threatening complications.4 Cardiovascular events noted in the perioperative period include myocardial infarction, arrhythmias and heart failure.68 There is a greater cardiac risk profile in patients with cirrhosis with the underlying non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) as compared to ethanol-related cirrhosis.69 The incidence of CAD in cirrhotic patients is as high as 25% and is associated with lower survival rate and new cardiovascular morbidity.70

Table 2.

Changes in Cardiac Function After Liver Transplantation.

| Study | Year | N | Design | Pre-LT Systolic Function |

Post-LT Systolic Function |

Pre-LT Diastolic Function |

Pre LT DT |

Post LT Diastolic Function |

Post LT Other Echo variables |

Mean Follow up Post LT | Post LT Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF | EF | E/A | DT (milliseconds) | E/A | LV Wall Thickness | LA Enlargement | LV Wall Thickness | ||||||

| Theraponodos et al57 | 2002 | 40 | Prospective | Normal∗∗ | Normal∗∗ | 1.23 | 0.96∗ | 0.9 cm | 1.07 cm∗▽ | 57 months | |||

| Sonny et al58 | 2016 | 243 | Retroprospective | 59 | 57∗ | 93 g/m2 | 34.2 ml/m2 | 106 g/m2∗ | 5.2 years | ||||

| Torregrosa et al53 | 2015 | 15 | Prospective | 73 | 67∗ | 1.1 | 241 | 1 | 115 g/m2 | 41∗ | 97 g/m2∗ | 9 months | |

| Acosta et al59 | 1999 | 30 | Retroprospective | 64 | 62 | 1.32 | 1.01∗ | 1 cm | 1 cm | 21 months | |||

| Dowsley et al60 | 2012 | 107 | Retroprospective | 68 | 65∗ | 1.1 | 1.1 | 99 g/m2 | 34 ml/m2 | 100 g/m2 | 2.6 months | 24% had HF after LT | |

| Chen et al61 | 2016 | 41 | Prospective | 66 | 65 | 1 | 0.97 | 1.1 cm | 1.2 cm∗▽ | 18 months | |||

Abbreviations: LT, liver transplantation; DT, deceleration time; EF, ejection fraction; HF, heart failure; LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium; Echo, echocardiography.

Advanced cardiac imaging

Techniques such as dobutamine stress echocardiography, nuclear myocardial perfusion scanning, real-time stress myocardial contrast perfusion echocardiography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging are the advanced techniques which can evaluate a lot of parameters, but the use of these techniques is center specific.71 Most transplant units use 2D echocardiography for screening CCM, which is highly operator-dependent. The gold standard method for non-invasive diagnosis of CCM is cardiovascular magnetic resonance with T1-mapping including assessment of the myocardial extracellular volume (ECV), an indicator of intrinsic myocardial abnormalities. The T1 relaxation time is an indicator of ventricular tissue integrity, and the T2 relaxation time is an indicator of edema within the ventricular walls.4,28 One possible mechanism of diastolic dysfunction is increased myocardial collagen content, which leads to increased LV stiffness and diffuse interstitial fibrosis. Higher myocardial ECV was found in patients with ascites, in those with a higher Child–Turcotte–Pugh (CTP) score and those who were transplanted or received TIPS. Moreover, a higher myocardial ECV was related to the advancement of the severity of the liver disease, inflammation, and survival. Most likely these changes also reflect myocardial fibrosis as a structural element of CCM. Calculation of the ECV fraction is a marker of pericellular edema and may be predictive of the reversible component of CCM.18 Left atrial enlargement has been repeatedly reported in cirrhosis. Myocardial fibrosis can be noninvasively characterized with cardiac MR imaging by using late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) sequences. LGE represents irreversible replacement fibrosis, while ECV represents reversible fibrosis.4,28

Electrophysiological abnormalities

Electrophysiological abnormalities in the context of CCM include prolonged QTc interval, electromechanical desynchrony and chronotropic incompetence.3 The QT interval which represents ventricular systolic duration was found to be prolonged by 30–50% in liver cirrhosis and contributes to the development of ventricular arrhythmias.72 Chronotropic incompetence is a defective cardiac response which reflects the difference between the electrical and mechanical systole time and appears related to compromised hyperdynamic circulation.73 The prolonged QT interval is associated with severity of liver disease, degree of portal hypertension, and shunting of splanchnic blood. This manifests clinically as heart rate variability, pro-BNP levels and noradrenaline levels in blood plasma.74,75 In addition, it is related to poor survival rate in cirrhotic patients with esophageal varices.76 Many studies have claimed partial reversal in prolongation of QT interval after liver transplantation as well as correction of the QTc interval after treatment with non-selective beta-blockers.63,77, 78, 79, 80 However, the improvement of cardiac function, as well as the effect on patient survival rate after treatment with non-selective beta-blockers, and dosing protocol is still under investigation.81

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in children

The CCM in the pediatric population is understudied due to lack of robust diagnostic criteria. Most information is available from young patients with biliary atresia who were assessed for cardiac disease before liver transplantation. The diagnosis is based on old criteria of early to late phase aortic filling (E/A ratio), a prolonged deceleration time or isovolumetric times to identify LVDD. Gorgis et al reported that up to 50% of children listed for transplant due to biliary atresia (BA) had pediatric cardiomyopathy, which was seen as reduced ejection fraction to indicate systolic dysfunction, left ventricular mass index ≥95 g/m2, relative wall thickness of LV ≥ 0.042, or diastolic dysfunction. BA-associated CCM leads to risk of waitlist deaths, increased multiorgan dysfunction, need for intensive care stay, and organ support and is independently associated with risk of mortality.82 Another study by Khemakanok et al demonstrated 20 pediatric pre-transplant patients with cirrhosis, several cardiac abnormalities including LV enlargement (50%), increased LV mass (95%), abnormal LV geometry (95%), hyperdynamic LV systolic function (60%), LVDD (60%), and high cardiac index (75%) on pre-surgical assessment.83

Cardiac biomarkers in cirrhotic cardiomyopathy

The two main biomarkers reported for the diagnosis of LV dysfunction are atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), which are released due to strain of the cardiac atrial and ventricular walls, respectively. Atrial natriuretic peptide is indicative of increased intravascular volume and LV hypertrophy and can be visualized as an enlarged LA on echocardiography or advanced imaging. An increased ANP is associated with increased filling pressures and tends to be elevated in patients with ascites.84

Because patients with liver disease already have high levels of catecholamines, the exact cut offs may differ for some metabolites such as N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), troponin I, creatine kinase-MB fraction, and plasma renin activity.85 Troponin I and T are structural proteins released from damaged myocardium such as infarction or myocarditis. Troponin I is elevated in patients with alcohol associated cirrhosis, stroke volume index and LV mass. It is not a reliable marker of heart failure alone as it is also an inflammatory marker and is elevated in critically ill patients with cirrhosis. At our center, we use a combination of NT-pro BNP, troponin I, aldosterone/PRA ratio to assess for heart failure, myocarditis, hemodynamic insults such as paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction. Novel biomarkers such as heart-type fatty acid binding protein (h-FABP), galectin-3, and myeloperoxidase are under evaluation.41

Specific treatment for cirrhotic cardiomyopathy

Various studies have shown the reversal of major cardiac events such as cardiac output, systolic and diastolic function, and exercise capacity along with improvement in QT interval prolongation after one year of liver transplantation.62 Although beta blockers may be harmful in decompensated patients with low mean arterial pressure (MAP), non-selective beta-blockers (NSBBs) have shown good efficacy in the improvement of QT interval prolongation and hyperdynamic circulation.83, 84, 85 Patients with systolic dysfunction and advanced grades of LVDD rarely tolerate long term beta blocker therapy. The simplest parameter for monitoring the tolerance is ambulatory assessment of blood pressure. If the MAP remains ≥70 mmHg, adverse effects such as hepatorenal syndrome or refractory ascites are less likely in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. The definitive means of assessing response to NSBB is to observe a 10% reduction in the hepatic venous pressure gradient, the higher doses of NSBB required to achieve HVPG reduction may lower cardiac output. If the MAP falls in an overzealous attempt to achieve effective portal pressure reduction, then deleterious effects of NSBB will be seen.39

The maximum tolerated dose of non-selective beta blockers can be prescribed, provided MAP and heart rate monitoring is feasible. If MAP is reduced, it implies that the cardiac output is falling and that is when the renin angiotensin system is activated with acute kidney injury and increasing ascites.2

However, the clinical benefit of improvement of QT interval in cirrhosis is not known. Similarly, although terlipressin is useful to treat type 1 HRS; it can further reduce cardiac function in patients with CCM. Effects of secondary hyperaldosteronism such as hypertension and volume expansion can be nullified using aldosterone antagonist therapy such as spironolactone, which is prescribed as a diuretic in cirrhosis leading to improved survival rate and reduction in hospitalization in heart failure. Myocardial ECV can also be used as a surrogate for myocardial fibrosis to assess for reversal on therapy.86,87 Ivabradine is a novel heart rate lowering drug that works by selectively binding to the sinoatrial-node HCN channel which specifically inhibits the cardiac pacemaker current (If). This channel is a mixed Na–K inward current channel that controls the diastolic depolarization of the SA node and effectively controls HR in a dose-dependent fashion. Ivabradine prolongs the diastolic depolarization, reduces the firing rate of the SA node and allows better relaxation of the LV during diastole improving CO without any adverse effect on the myocardial contractility, blood pressure or intra cardiac conduction. However, there have been cases of atrial fibrillation associated with high doses of ivabradine. Another side effect is luminous phenomena called phosphenes reported by patients due to partial inhibition of the retinal Ih current, which differentiates temporal stimuli in the retina.88 However, at the low doses prescribed in combination with betablockers, these adverse events were not reported in the primary study from India.39 The use of repurposed drugs for heart failure shows promise to alleviate the diseases of the cardio–hepatic–renal axis, due to common precipitants for disease such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome.89 (Table 3) Figure 4 shows the diagnostic algorithm and drug targets in CCM.

Table 3.

Molecular Mediators of CCM and Potential Targets of Therapy.

| S. No | Mediator | Mechanism | Therapeutic Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endocannabinoids | Anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG) act via the cannabinoid −1 (CB-1) receptor. AEA results in a strong CB1 and TRPV1 receptor dependent vasodilation of mesenteric vessels. AEA causes vasoconstriction of an isolated perfused liver in bile duct ligated rats as animal models of CCM. Thromboxane A2 causes the increased intrahepatic resistance. |

Blockade of the CB1 receptors is possible using drugs such as rimonabant. CB1 deficiency increases the splanchnic vascular resistance in cirrhosis leading to reduced mesenteric arterial blood flow, reduced fibrosis, and improved survival in animal models.81 Ciprofloxacin can also cause a decrease in endotoxemia, but also a fall in hepatic AEA and 2-AG. It can cause a decrease and increase in the expression of CB1 and CB2 receptors, respectively.82 |

|

| Heme oxygenase (HO) | Heme oxygenase-1, a cytoprotective factor, is responsible for oxidation of hemoglobin to carbon monoxide, biliverdin and iron. CO is a secondary messenger, such as NO, and heme oxygenase upregulation is noted in cirrhosis. |

HO-1 ameliorates cellular injury by exerting antiapoptotic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Hemin can thus have a cardioprotective role by increased expression of HO-1.83 |

|

| TNF α | TNF α induces the formation of endo cannabinoids, which depresses cardiac contractility via iNOS | iNOS inhibitors can reverse CCM in a bile duct ligated rat model. The NOS inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) is one such drug used in animal models.84 |

|

| Beta adrenergic receptor response | The cardiac muscle beta adrenergic receptors respond to the neurohormone Norepinephrine. Reduced beta adrenoreceptor response is due to downregulation of the receptors due to chronic hyperstimulation by catecholamine. |

Role of Beta blockers in CCM may improve outcomes in early stage and worsen outcomes in late stages.2 | |

| Bile acid | Bile acids exert a negative-inotropic effect on the heart. Farnesoid X-activated receptor have been found in cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells. Elevated BA levels cause cardiac arrhythmias and disruption of ion channels. |

Ursodeoxycholic acid and FXR signaling regulators may have beneficial effect on the heart. Obeticholic acid has been proposed as a possible mediator.13 |

|

| Myocardial fibrosis and Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. | Prolonged beta-adrenergic stimulation and adverse catecholamine profile leads to remodeling. Early changes

|

Beta blockers Anti-inflammatory drugs. |

|

| Ion Channel Defects | Ca2+, K+, and Na+ ion fluxes maintain myocardium action potentials. QTc prolongation Reduced capacity for ion transport is noted in animal models of CCM. |

Ivabradine a novel If channel inhibitor has shown promise in a recent study.35 |

Abbreviations: CCM, cirrhotic cardiomyopathy; BA, bile acids.

Figure 4.

Diagnostic algorithm and drug targets in cirrhotic cardiomyopathy.

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, among a broad spectrum of cardiac complications in cirrhosis, is characterized by systolic and diastolic cardiac dysfunction and electrocardiographic changes. However, it is seen more in NASH-related cirrhotic patients, who have an additional risk of developing cardiac complications. Cirrhosis contributes to a including cirrhotic cardiomyopathy owing to various pathological conditions interlinked at the cellular and molecular level. A hyperdynamic circulatory state caused due to excessive release of vasodilators in a pro-inflammatory condition of cirrhosis, along with negative–inotropic pathways contributes to the development of a compromised cardiac function. Electrocardiography, 2D echocardiography with tissue Doppler, or speckle tracking are the routine diagnostic tests used to diagnose CCM. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance is an excellent objective method of calculating the stroke volume, ventricular and atrial chamber dimensions, cardiomyocyte edema and fibrosis. Although early CCM is asymptomatic, it can be unmasked by pharmacological stress, sepsis, surgery critical illness, or exercise. The presence of CCM often worsens the outcomes of surgical procedures of liver transplantation and TIPS insertion. The appropriate use of drugs such as beta blockers and ivabradine offers hope and needs further scrutiny. Liver transplantation is known to reverse or ameliorate the functional and structural changes in CCM.

Credit authorship contribution statement

HK drafted the initial manuscript and performed the literature review. The manuscript was edited and revised by MP. All figures were drawn by MP. Both the authors have approved the final draft.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Financial Support

This review is partially supported by an Indian Council of Medical Research- Department of Health Research (ICMR-DHR) grant (GIA/2019/000281/PRCGIA) awarded to MP.

References

- 1.Jepsen P., Vilstrup H., Andersen P.K. The clinical course of cirrhosis: the importance of multistate models and competing risks analysis. Hepatology. 2015;62:292–302. doi: 10.1002/hep.27598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Premkumar M., Devurgowda D., Vyas T., et al. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction is associated with renal dysfunction, poor survival and low health related quality of life in cirrhosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019;9:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Møller S., Henriksen J.H. Cardiovascular complications of cirrhosis. Gut. 2008;57:268–278. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.112177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H., Jayakumar S., Traboulsi M., Lee S.S. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy: implications for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2017;23:826–835. doi: 10.1002/lt.24768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagueh S.F., Smiseth O.A., Appleton C.P., et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American society of echocardiography and the European association of cardiovascular imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:1321–1360. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jew082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho M.V.H., Kroll P.C., Kroll R.T.M., Carvalho V.N. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy: the liver affects the heart. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2019;52 doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20187809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wehmeyer M.H., Heuer A.J., Benten D., et al. High rate of cardiac abnormalities in a postmortem analysis of patients suffering from liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:866–872. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortiz-Olvera N.X., Castellanos-Pallares G., Gómez-Jiménez L.M., et al. Anatomical cardiac alterations in liver cirrhosis: an autopsy study. Ann Hepatol. 2011;10:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izzy M., VanWagner L.B., Lin G., et al. Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy Consortium Redefining cirrhotic cardiomyopathy for the modern era. Hepatology. 2020;71:334–345. doi: 10.1002/hep.30875. Epub 2019 Oct 11. Erratum in: Hepatology. 2020;72(3):1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz-del-Arbol L., Monescillo A., Arocena C., et al. Circulatory function and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2005;42:439–447. doi: 10.1002/hep.20766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krag A., Bendtsen F., Henriksen J.H., Møller S. Low cardiac output predicts development of hepatorenal syndrome and survival in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Gut. 2010;59:105–110. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.180570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izzy M., Oh J., Watt K.D. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy after transplantation: neither the transient nor innocent bystander. Hepatology. 2018;68:2008–2015. doi: 10.1002/hep.30040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao J., Liu X., Wang B., et al. Farnesoid X receptor deletion improves cardiac function, structure and remodeling following myocardial infarction in mice. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:673–679. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voiosu A., Wiese S., Voiosu T., Bendtsen F., Møller S. Bile acids and cardiovascular function in cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2017;37:1420–1430. doi: 10.1111/liv.13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y.T., Swales K.E., Thomas G.J., Warner T.D., Bishop-Bailey D. Farnesoid x receptor ligands inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell inflammation and migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2606–2611. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.152694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H., Ma Z., Lee S.S. Contribution of nitric oxide to the pathogenesis of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in bile duct-ligated rats. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:937–944. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rainer P.P., Primessnig U., Harenkamp S., et al. Bile acids induce arrhythmias in human atrial myocardium--implications for altered serum bile acid composition in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart. 2013;99:1685–1692. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Premkumar M., Rangegowda D., Kajal K., Khumuckham J.S. Noninvasive estimation of intravascular volume status in cirrhosis by dynamic size and collapsibility indices of the inferior vena cava using bedside echocardiography. JGH Open. 2019;3:322–328. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Premkumar M., Kajal K., Kulkarni A.V., Gupta A., Divyaveer S. Point-of-Care echocardiography and hemodynamic monitoring in cirrhosis and acute-on-chronic liver failure in the COVID-19 era. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36:511–523. doi: 10.1177/0885066620988281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arroyo V. Microalbuminuria, systemic inflammation, and multiorgan dysfunction in decompensated cirrhosis: evidence for a nonfunctional mechanism of hepatorenal syndrome. Hepatol Int. 2017;11:242–244. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9784-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coenraad M.J., Porcher R., Bendtsen F. Hepatic and cardiac hemodynamics and systemic inflammation in cirrhosis: it takes three to tango. J Hepatol. 2018;68:887–889. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Møller S., Bendtsen F. Cirrhotic multiorgan syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:3209–3225. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3752-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernardi M., Caraceni P. Novel perspectives in the management of decompensated cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:753–764. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turco L., Garcia-Tsao G., Magnani I., et al. Cardiopulmonary hemodynamics and C-reactive protein as prognostic indicators in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;68:949–958. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karagiannakis D.S., Vlachogiannakos J., Anastasiadis G., Vafiadis-Zouboulis I., Ladas S.D. Frequency and severity of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy and its possible relationship with bacterial endotoxemia. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:3029–3036. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2693-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeffer M.A., Shah A.M., Borlaug B.A. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in perspective. Circ Res. 2019;124:1598–1617. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.313572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maleki M., Vakilian F., Amin A. Liver diseases in heart failure. Heart Asia. 2011;3:143–149. doi: 10.1136/heartasia-2011-010023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Møller S., Henriksen J.H. Cardiovascular complications of cirrhosis. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:44–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.112177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Møller S., Lee S.S. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. J Hepatol. 2018;69:958–960. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver Corrigendum to "EASL clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis" [J Hepatol 69 (2018) 406-460] J Hepatol. 2018;69:1207. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong F., Girgrah N., Graba J., Allidina Y., Liu P., Blendis L. The cardiac response to exercise in cirrhosis. Gut. 2001;49:268–275. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krag A., Bendtsen F., Mortensen C., Henriksen J.H., Møller S. Effects of a single terlipressin administration on cardiac function and perfusion in cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1085–1092. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32833a4822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sampaio F., Lamata P., Bettencourt N., et al. Assessment of cardiovascular physiology using dobutamine stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance reveals impaired contractile reserve in patients with cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:61. doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0157-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kazankov K., Holland-Fischer P., Andersen N.H., et al. Resting myocardial dysfunction in cirrhosis quantified by tissue Doppler imaging. Liver Int. 2011;31:534–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rastogi A., Novak E., Platts A.E., Mann D.L. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical outcomes for heart failure patients with a mid-range ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1597–1605. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruíz-del-Árbol L., Achécar L., Serradilla R., et al. Diastolic dysfunction is a predictor of poor outcomes in patients with cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and a normal creatinine. Hepatology. 2013;58:1732–1741. doi: 10.1002/hep.26509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krag A., Bendtsen F., Burroughs A.K., Møller S. The cardiorenal link in advanced cirrhosis. Med Hypotheses. 2012;79:53–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kazory A., Ronco C. Hepatorenal syndrome or Hepatocardiorenal syndrome: revisiting basic concepts in view of emerging data. Cardiorenal Med. 2019;9:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000492791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Premkumar M., Rangegowda D., Vyas T., et al. Carvedilol combined with ivabradine improves left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, clinical progression, and survival in cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54:561–568. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiese S., Hove J., Mo S., et al. Myocardial extracellular volume quantified by magnetic resonance is increased in cirrhosis and related to poor outcome. Liver Int. 2018;38:1614–1623. doi: 10.1111/liv.13870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saner F.H., Neumann T., Canbay A., et al. High brain-natriuretic peptide level predicts cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in liver transplant patients. Transpl Int. 2011;24:425–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glenn T.K., Honar H., Liu H., ter Keurs H.E., Lee S.S. Role of cardiac myofilament proteins titin and collagen in the pathogenesis of diastolic dysfunction in cirrhotic rats. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1249–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alqahtani S.A., Fouad T.R., Lee S.S. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:59–69. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karagiannakis D.S., Vlachogiannakos J., Anastasiadis G., Vafiadis-Zouboulis I., Ladas S.D. Diastolic cardiac dysfunction is a predictor of dismal prognosis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Int. 2014;8:588–594. doi: 10.1007/s12072-014-9544-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pozzi M., Carugo S., Boari G., et al. Evidence of functional and structural cardiac abnormalities in cirrhotic patients with and without ascites. Hepatology. 1997;26:1131–1137. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nazar A., Guevara M., Sitges M., et al. LEFT ventricular function assessed by echocardiography in cirrhosis: relationship to systemic hemodynamics and renal dysfunction. J Hepatol. 2013;58:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cesari M., Frigo A.C., Tonon M., Angeli P. Cardiovascular predictors of death in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2018;68:215–223. doi: 10.1002/hep.29520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merli M., Torromeo C., Giusto M., Iacovone G., Riggio O., Puddu P.E. Survival at 2 years among liver cirrhotic patients is influenced by left atrial volume and left ventricular mass. Liver Int. 2017;37:700–706. doi: 10.1111/liv.13287. Epub 2016 Nov 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cacciapuoti F., Magro V.M., Caturano M., Lama D., Cacciapuoti F. The role of ivabradine in diastolic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. A Doppler-echocardiographic study. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2017;27:126–131. doi: 10.4103/jcecho.jcecho_6_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lunseth J.H., Olmstead E.G., Abboud F. A study of heart disease in one hundred eight hospitalized patients dying with portal cirrhosis. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1958;102:405–413. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1958.00030010405009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Møller S., Danielsen K.V., Wiese S., Hove J.D., Bendtsen F. An update on cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:497–505. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2019.1587293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iskandrian A.S., Helfeld H., Lemlek J., Lee J., Iskandrian B., Heo J. Differentiation between primary dilated cardiomyopathy and ischemic cardiomyopathy based on right ventricular performance. Am Heart J. 1992;123:768–773. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90518-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Busk T.M., Bendtsen F., Poulsen J.H., et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: impact on systemic hemodynamics and renal and cardiac function in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018;314:G275–G286. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00094.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cazzaniga M., Salerno F., Pagnozzi G., et al. Diastolic dysfunction is associated with poor survival in patients with cirrhosis with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Gut. 2007;56:869–875. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.102467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rabie R.N., Cazzaniga M., Salerno F., Wong F. The use of E/A ratio as a predictor of outcome in cirrhotic patients treated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2458–2466. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Busk T.M., Bendtsen F., Møller S. Cardiac and renal effects of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:523–530. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835d09fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merli M., Valeriano V., Funaro S., et al. Modifications of cardiac function in cirrhotic patients treated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ripoll C., Yotti R., Bermejo J., Bañares R. The heart in liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2011;54:810–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.003. Epub 2010 Nov 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harinstein M.E., Iyer S., Mathier M.A., et al. Role of baseline echocardiography in the preoperative management of liver transplant candidates. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1852–1855. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Pietri L., Mocchegiani F., Leuzzi C., Montalti R., Vivarelli M., Agnoletti V. Transoesophageal echocardiography during liver transplantation. World J Hepatol. 2015 Oct 18;7:2432–2448. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i23.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Therapondos G., Flapan A.D., Plevris J.N., Hayes P.C. Cardiac morbidity and mortality related to orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1441–1453. doi: 10.1002/lt.20298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dowsley T.F., Bayne D.B., Langnas A.N., et al. Diastolic dysfunction in patients with end-stage liver disease is associated with development of heart failure early after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2012;94:646–651. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31825f0f97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Torregrosa M., Aguadé S., Dos L., et al. Cardiac alterations in cirrhosis: reversibility after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2005;42:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Therapondos G., Flapan A.D., Dollinger M.M., Garden O.J., Plevris J.N., Hayes P.C. Cardiac function after orthotopic liver transplantation and the effects of immunosuppression: a prospective randomized trial comparing cyclosporin (Neoral) and tacrolimus. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:690–700. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.34381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sonny A., Ibrahim A., Schuster A., Jaber W.A., Cywinski J.B. Impact and persistence of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2016;30:986–993. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruiz-del-Árbol L., Serradilla R. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11502–11521. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11502. PMID: 26556983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen Y., Chan A.C., Chan S.C., et al. A detailed evaluation of cardiac function in cirrhotic patients and its alteration with or without liver transplantation. J Cardiol. 2016;67:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mandell M.S., Lindenfeld J., Tsou M.Y., Zimmerman M. Cardiac evaluation of liver transplant candidates. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3445–3451. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khan R.S., Newsome P.N. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver transplantation. Metabolism. 2016;65:1208–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vanwagner L.B., Bhave M., Te H.S., Feinglass J., Alvarez L., Rinella M.E. Patients transplanted for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are at increased risk for postoperative cardiovascular events. Hepatology. 2012;56:1741–1750. doi: 10.1002/hep.25855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sehgal L., Srivastava P., Pandey C.K., Jha A. Preoperative cardiovascular investigations in liver transplant candidate: an update. Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60:12–18. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.174870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bernardi M., Maggioli C., Dibra V., Zaccherini G. QT interval prolongation in liver cirrhosis: innocent bystander or serious threat? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6:57–66. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fede G., Privitera G., Tomaselli T., Spadaro L., Purrello F. Cardiovascular dysfunction in patients with liver cirrhosis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:31–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ytting H., Henriksen J.H., Fuglsang S., Bendtsen F., Møller S. Prolonged Q-T(c) interval in mild portal hypertensive cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2005;43:637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Henriksen J.H., Gülberg V., Fuglsang S., et al. Q-T interval (QT(C)) in patients with cirrhosis: relation to vasoactive peptides and heart rate. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2007;67:643–653. doi: 10.1080/00365510601182634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trevisani F., Di Micoli A., Zambruni A., et al. QT interval prolongation by acute gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2012;32:1510–1515. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2012.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Adigun A.Q., Pinto A.G., Flockhart D.A., et al. Effect of cirrhosis and liver transplantation on the gender difference in QT interval. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:691–694. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shin W.J., Kim Y.K., Song J.G., et al. Alterations in QT interval in patients undergoing living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:170–173. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Henriksen J.H., Bendtsen F., Hansen E.F., Møller S. Acute non-selective beta-adrenergic blockade reduces prolonged frequency-adjusted Q-T interval (QTc) in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2004;40:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zambruni A., Trevisani F., Di Micoli A., et al. Effect of chronic beta-blockade on QT interval in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2008;48:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Silvestre O.M., Farias A.Q., Ramos D.S., et al. β-Blocker therapy for cirrhotic cardiomyopathy: a randomized-controlled trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:930–937. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gorgis N.M., Kennedy C., Lam F., et al. Clinical consequences of cardiomyopathy in children with biliary atresia requiring liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2019;69:1206–1218. doi: 10.1002/hep.30204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khemakanok K., Khositseth A., Treepongkaruna S., et al. Cardiac abnormalities in cirrhotic children: pre- and post-liver transplantation. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:518–524. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9674-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Henriksen J.H., Gøtze J.P., Fuglsang S., Christensen E., Bendtsen F., Møller S. Increased circulating pro-brain natriuretic peptide (proBNP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) in patients with cirrhosis: relation to cardiovascular dysfunction and severity of disease. Gut. 2003;52:1511–1517. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.10.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Raedle-Hurst T.M., Welsch C., Forestier N., et al. Validity of N-terminal propeptide of the brain natriuretic peptide in predicting left ventricular diastolic dysfunction diagnosed by tissue Doppler imaging in patients with chronic liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:865–873. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282fb7cd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wiese S., Mortensen C., Gøtze J.P., et al. Cardiac and proinflammatory markers predict prognosis in cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014;34:e19–e30. doi: 10.1111/liv.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cesari M., Letizia C., Angeli P., Sciomer S., Rosi S., Rossi G.P. Cardiac remodeling in patients with primary and secondary aldosteronism: a tissue Doppler study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.004815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Swedberg K., Komajda M., Böhm M., et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2010;376:875–885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yoon K.T., Liu H., Lee S.S. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22:45. doi: 10.1007/s11894-020-00783-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]