Abstract

Objectives:

The COVID-19 pandemic may contribute to heightened anxiety among older adults with chronic conditions, which might be attenuated by social resources. This study examined how social contact and emotional support were linked to anxiety symptoms among adults aged 50 and older with chronic conditions, and whether these links varied by age.

Methods:

Participants included 705 adults (M = 64.61 years, SD = 8.85, range = 50 – 94) from Michigan (82.4%) and 33 other U.S. states who reported at least one chronic condition and completed an anonymous online survey between May 14 and July 9, 2020.

Results:

Multiple regression models revealed among younger people, those reporting more frequent social contact had significantly lower anxiety symptoms. Emotional support was not significantly associated with anxiety symptoms.

Conclusions:

More frequent social contact was linked to lower anxiety symptoms for younger but not older individuals. Emotional support was not significantly associated with anxiety symptoms.

Clinical Implications:

Interventions to manage anxiety during the pandemic among older adults with chronic conditions may benefit from strategies to safely increase social contact, especially for middle-aged adults.

Keywords: chronic disease, chronic illness, coronavirus, stress, social relations

Given the adverse mental health consequences of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic (Emerson, 2020), it is important to examine potential protective factors among high-risk populations. In particular, older adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020a) and people with pre-existing conditions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020b) were urged to limit in-person contact with others due to their susceptibility to the virus. Reduced social engagement among older adults living with chronic conditions may have had negative implications for mental health. This may have especially been the case among older individual who are typically more focused on maintaining close social ties than younger individuals (Charles & Carstensen, 2010). We examined how social contact and emotional support during the early months of the pandemic were associated with anxiety symptoms among adults aged 50 and older with chronic conditions, and whether these links varied by age.

Background and Theoretical Framework

According to stress process models of mental health (Pearlin, 1999), circumstances of chronic stress can negatively impact well-being. The early months of the COVID-19 pandemic represented a persistent source of stress and uncertainty, along with fewer opportunities for social engagement, all of which may have contributed to psychological distress (Emerson, 2020; Van Orden et al., 2020). In this study, we focus on anxiety symptoms as a key outcome of mental health among older adults with chronic conditions during the pandemic. Previous research indicates that the pandemic may heighten anxiety (Bäuerle et al., 2020), especially among older people with chronic conditions due to worries about severe illness from COVID-19 (El-Zoghby et al., 2020; Girdhar et al., 2020; Mazza et al., 2020). More broadly, anxiety symptoms are also an important outcome in middle and later life because they are associated with greater functional disability (Baxter et al., 2014b).Stress process models further posit that the mental health consequences of stress may be attenuated by social resources, including social contact and emotional support (Pearlin, 1999). Although both of these social resources are related, they are distinct in their nature of social engagement. Social contact refers to simply being in touch with other individuals (either in-person or virtually). By contrast, emotional support is a type of social support given to or received from others that includes listening to one’s worries or concerns and being available when they are feeling stressed or upset (Fingerman et al., 2011). Research on health care workers has found that social support during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with lower levels of stress and anxiety (Du et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020). This work suggests that social contact and emotional support may help to maintain mental health among older adults with chronic conditions.

Socioemotional selectivity theory proposes as people age, they become increasingly motivated to maintain close social ties (Charles & Carstensen, 2010). Consequently, social contact and emotional support may be more critical to managing anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic for older people (Birditt et al., 2020; Van Orden et al., 2020). Alternatively, social contact and emotional support may be less consequential among older adults because of their enhanced capacity for coping during crises. Perhaps in part due to past experiences with other crises, older individuals have demonstrated better coping during the pandemic (Birditt et al., 2020; Carstensen et al., 2020). Previous theoretical and empirical work suggest the importance of understanding whether social contact and emotional support are more strongly associated with lower anxiety symptoms among older than younger individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. This knowledge would provide insight into targeted interventions and preventative measures to reduce anxiety among adults aged 50 and older who are living chronic conditions during the current pandemic and in future public health crises.

The Present Study

This study builds on understanding mental health and coping during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic by examining how social contact and emotional support were linked to anxiety symptoms among adults aged 50 and older with chronic conditions. Controlling for key variables that are linked to anxiety symptoms during the pandemic, including sociodemographic characteristics (Bui et. al., 2020; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020; Shah et. al., 2020), health characteristics (Pettinicchio et. al., 2021; Wu et. al., 2021), and pandemic-related stress (Caycho-Rodriguez et. al., 2021), we hypothesized that people who reported more frequent social contact and more frequent emotional support had lower anxiety symptoms, and that these links were stronger for older individuals.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The sample for this cross-sectional study included 788 individuals recruited between May 14 and July 9, 2020. To recruit, we used the UMHealthResearch.org opt-in database, the Healthier Black Elders Center Participant Resource Pool of African American adults aged 55 and older, social media posts, emails shared with the study team’s contacts, and word of mouth. Individuals were eligible if they were aged 50 or older, were current U.S. residents, and reported a current diagnosis of at least one chronic mental or physical condition, defined as a condition lasting three months or longer.

Participants completed an anonymous online survey using the Qualtrics platform that took approximately 20 minutes. Only individuals who gave electronic informed consent were able to access the survey. Participants were not compensated. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan.

Of the 788 participants, we removed 11 who consented but did not respond to any survey questions. We then removed 13 who reported they did not have any chronic conditions listed in the survey and did not have any other mental or physical health problems. Of the remaining 764, we removed 40 with no data on chronic conditions and 19 with missing data on other study variables. The final analytic sample included 705 individuals (M = 64.61 years, SD = 8.85, range = 50 – 94). Compared with the 59 individuals removed due to missing data, participants in this study were less likely to be a person of color (χ2 (1, N = 761) = 5.01, p = .025) and more likely to have a bachelor’s degree or more education (χ2 (1, N = 761) = 8.10, p = .004).

Measures

Outcome

Anxiety symptoms.

Participants were asked, since the pandemic, in an average week, how often: (a) do they feel nervous, anxious, or on edge?; and (b) are they not able to stop or control worrying? (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day) using an adapted measure (GAD-2; Kroenke et al., 2007). We created summed scores. The Spearman-Brown coefficient was .80. We used a cut-off score of 3 or higher to reflect clinically significant anxiety (Plummer et al., 2016).

Predictors

Social contact.

Participants reported how often they are communicating with people outside their households since the pandemic (Cawthon et al., 2020). Responses (1 = daily, 2 = a few times per week, 3 = once a week, 4 = a few times per month, 5 = once a month, 6 = less than once a month, 7 = never) were reverse-coded. In descriptive analyses, we examined reports of how participants continued to stay in touch with people outside their households.

Emotional support.

Participants reported how often they have received emotional support from family members or friends (e.g., being available to listen to concerns and talk when you are feeling stressed or upset) since the pandemic an item adapted from prior research (Fingerman et al., 2011). Responses (1 = daily, 2 = a few times per week, 3 = once a week, 4 = a few times per month, 5 = once a month, 6 = less than once a month, 7 = never) were reverse-coded.

Moderator

Age.

We considered age in years as a moderator.

Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics.

We controlled for gender (1 = female, 0 = male or other), race/ethnicity (1 = people of color, 0 = non-Hispanic White), educational attainment (1 = bachelor’s degree or higher, 0 = less than a bachelor’s degree), marital status (1 = currently married/cohabiting with a partner, 0 = not currently married/cohabiting with a partner), and household size (number of adults and children currently in the household).

Health characteristics.

Participants reported on their overall physical health before the pandemic (1 = excellent to 5 = poor) using an adapted item from the SF-36 health survey that was reverse-coded (Merikangas et al., 2020; Ware, 1999). Participants reported whether they had been diagnosed by a physician (1 = yes, 0 = no) with any of 22 chronic conditions. We summed the number of conditions. Participant reports of their current limitations (1 = yes, limited a lot, 2 = yes, limited a little, 3 = no, not limited at all) in ten activities (e.g., vigorous activities, moderate activities) were reverse-coded and summed (Ware, 1999). Participants reported how much bodily pain (0 = none to 5 = very severe) they usually have since the pandemic (Ware, 1999).

Pandemic-related stress.

Subjective measures of pandemic-related stress were adapted from prior research (Merikangas et al., 2020). Participants separately reported the degree they worried about: (a) themselves and (b) friends or family becoming infected with COVID-19 (1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal). Mean scores were calculated. The Spearman-Brown coefficient was .84. Participants reported the extent they or their families have had financial problems created by pandemic-related changes (1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal). Participants also reported their experience (1 = yes, 0 = no) of 13 pandemic-related stressors (e.g., being an essential worker, own or family member infection) using adapted items (Merikangas et al., 2020; Polenick et al., 2021). We summed the number of stressors.

Statistical Analysis

First, we examined bivariate associations between age and major study variables. We next estimated multiple linear regressions to examine how social contact and emotional support (predictors) were associated with anxiety symptoms (outcome), and whether these links varied by age (moderator). In Step 1, we included age (moderator) and the covariates, which included sociodemographic characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, and household size), health characteristics (self-rated physical health, number of chronic conditions, functional limitations, and pain intensity), and pandemic-related stress (worry about COVID-19 infection, financial strain related to the pandemic, and total stressors related to the pandemic). In Step 2, we added social contact and emotional support as the predictors. In Step 3, we added two interaction terms (social contact × age and emotional support × age) to test the moderating effects of age. We examined the nature of significant interactions by estimating simple slopes at one standard deviation above and below the mean for age, which corresponded to ages 55.76 and 73.45. Continuous predictors and covariates were grand mean centered. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27.

Results

Table 1 presents participant background characteristics and scores on major variables. Participants ranged from 50 to 94 years of age. About half of the participants were aged 50–64 (50.8%; n = 358) and about half were aged 65–94 (49.2%; n = 347). On average, individuals reported social contact with people outside their households a few times per week and emotional support about once a week. About one-third (33.9%) had a score of 3 or higher on the GAD-2 scale, reflecting clinically significant anxiety (Plummer et al., 2016). Clinically significant anxiety was more common at younger ages, with clinically significant anxiety symptoms reported by 43.9% of participants aged 50–64 and by 23.6% of those aged 65 and older.

Table 1.

Background Characteristics and Scores on Major Study Variables Among Older Adults With Chronic Conditions.

| Variable | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.61 | 8.85 |

| Household size | 1.27 | 1.23 |

| Self-rated physical healtha | 3.16 | 0.91 |

| Number of chronic conditionsb | 3.63 | 2.09 |

| Functional limitationsc | 15.90 | 5.19 |

| Pain intensityd | 2.09 | 1.17 |

| Worry about COVID-19 infectiona | 3.28 | 0.99 |

| Financial strain related to the pandemica | 1.89 | 1.12 |

| Total stressors related to the pandemice | 1.50 | 1.63 |

| Social contact since the pandemicf | 6.25 | 0.98 |

| Emotional support since the pandemicf | 5.16 | 1.77 |

| Anxiety symptomsg | 2.04 | 1.80 |

| % | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 73.3 | |

| Male | 26.1 | |

| Other | 0.6 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| People of color | 16.7 | |

| Black or African American | 11.8 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1.0 | |

| Asian | 1.6 | |

| Hispanic | 1.1 | |

| Other | 1.7 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 83.3 | |

| Educational attainment | ||

| High school diploma or equivalent | 3.8 | |

| Vocational, technical, business, or trade school certificate or diploma | 3.3 | |

| Some college but no degree | 13.2 | |

| Associate’s degree | 8.1 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 30.8 | |

| Master’s, professional, or doctoral degree | 40.9 | |

| Currently working part-time or full-time | 33.8 | |

| Married or cohabiting with a partner | 59.1 | |

| Michigan resident | 82.4 | |

Note. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Range = 1 – 5.

Range = 0 – 22.

Range = 10 – 30.

Range = 0 – 5.

Range = 0 – 13.

Range = 1 – 7.

Range = 0 – 6.

N = 705 adults.

Participants stayed in touch with people outside their households most often through phone calls (93.3%), followed by email (75.2%), video calls (66.7%), social media (59.9%), speaking in person (39.9%), and postal mail (23.4%). Older age was positively correlated with social media use (r = .18, p < .001), but negatively correlated with email use (r = −.21, p < .001).

With regard to correlations between age and major study variables, older age was significantly correlated with less worry about infection (r = −.10, p = .007), lower financial strain (r = −.19, p < .001), fewer pandemic-related stressors (r = −.25, p < .001), more social contact (r = .08, p = .038), and lower anxiety symptoms (r = −.25, p < .001). Age was not significantly correlated with emotional support.

Table 2 presents the 22 chronic conditions assessed in this study and their prevalence in the sample. The most commonly reported chronic conditions were arthritis (61.0%), high blood pressure or hypertension (47.1%), hyperlipidemia or high cholesterol (43.1%), chronic pain condition (34.9%), and depression (34.9%). About one in four participants (24.8%) reported having an anxiety disorder.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Chronic Conditions Among Older Adults With Chronic Conditions.

| Condition | % |

|---|---|

| Mental health conditions | |

| Depression | 34.9 |

| Anxiety disorder | 24.8 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4.6 |

| Substance use disorder (including drug and alcohol disorders) | 2.3 |

| Dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease and other types) | 0.6 |

| Schizophrenia | 0.3 |

| Physical health conditions | |

| Arthritis | 61.0 |

| High blood pressure or hypertension | 47.1 |

| Hyperlipidemia or high cholesterol | 43.1 |

| Chronic pain condition | 34.9 |

| Asthma | 21.9 |

| Osteoporosis | 19.7 |

| Diabetes | 18.8 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 11.1 |

| Cancer (all except non-melanoma skin) | 10.3 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 8.3 |

| Coronary artery disease, coronary heart disease, or ischemic heart disease | 7.3 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5.5 |

| Stroke, cerebrovascular disease, or transient ischemic attack | 4.0 |

| Congestive heart failure | 3.3 |

| Hepatitis | 1.1 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | 0.3 |

| Other mental or physical health problemsa | 47.0 |

Note.

Endorsement of having other current mental or physical health problems not listed in the survey.

N = 705 adults.

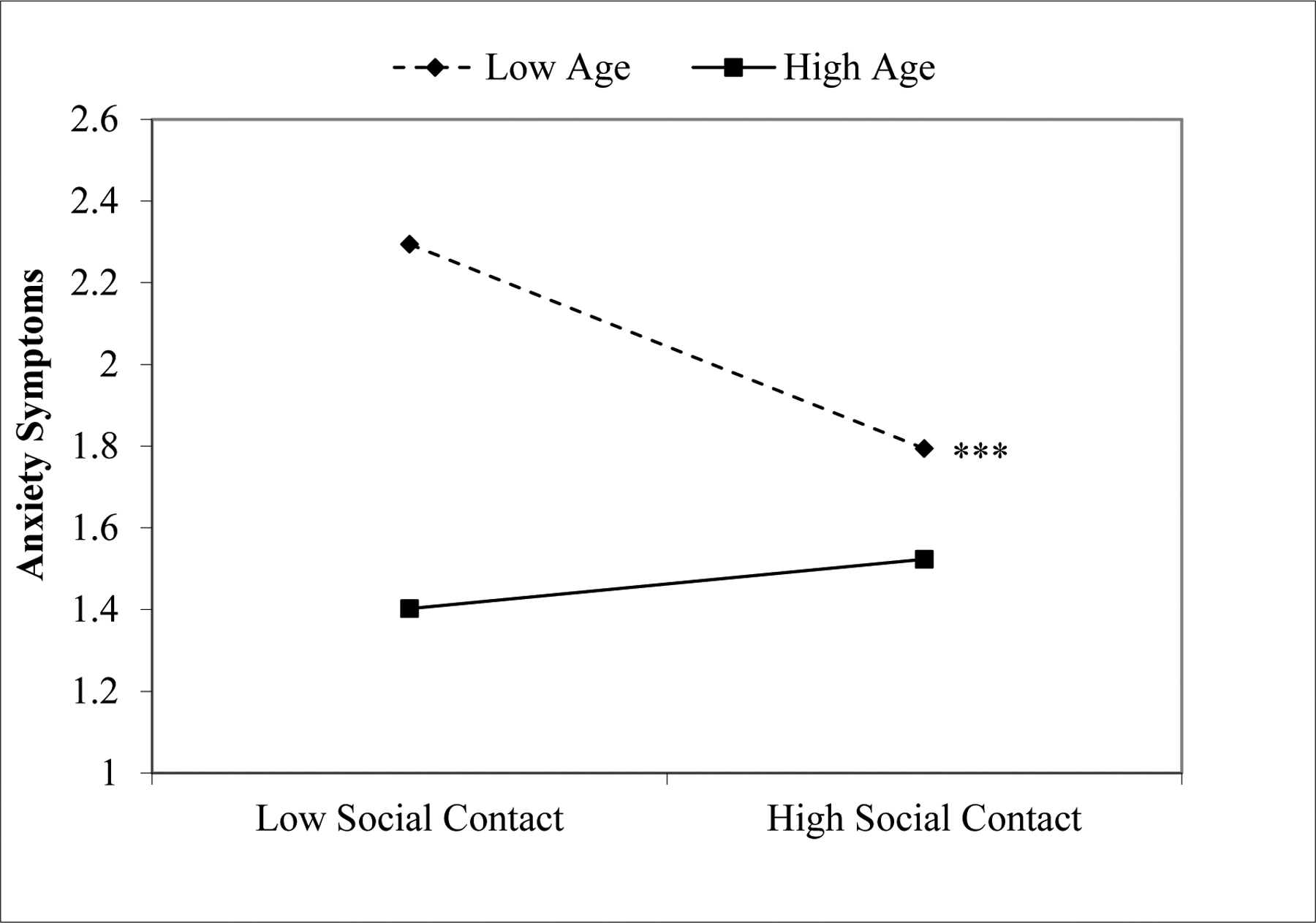

Table 3 shows parameter estimates from the multiple linear regressions. In Step 3, the association between social contact and anxiety symptoms was significantly moderated by age. More frequent social contact was significantly associated with lower anxiety symptoms among younger (B = −.26, SE = .08, p = .001, 95% CI: [−.40, −.11]) but not older (B = .06, SE = .09, p = .493, 95% CI: [−.11, .24]) individuals (Figure 1). Emotional support was not significantly linked to anxiety symptoms, and this link was not moderated by age.

Table 3.

Regressions Examining Links Between Social Resources and Anxiety Symptoms Since the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Older Adults With Chronic Conditions.

| Anxiety Symptoms | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |||||||

| Parameter | B | SE | 95% CI | B | SE | 95% CI | B | SE | 95% CI |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||||

| Age | −.03*** | .01 | −.05, −.02 | −.03*** | .01 | −.05, −.02 | −.03*** | .01 | −.05, −.02 |

| Gender (female) | .45** | .13 | .19, .71 | .45** | .13 | .18, .71 | .43** | .13 | .16, .69 |

| Race/ethnicity (person of color) | −.05 | .16 | −.35, .26 | −.06 | .16 | −.37, .24 | −.08 | .15 | −.38, .22 |

| Education (bachelor’s or higher) | .07 | .13 | −.18, .32 | .09 | .13 | −.17, .34 | .12 | .13 | −.13, .37 |

| Marital status (spouse/cohabiting partner) | −.19 | .13 | −.45, .06 | −.22 | .13 | −.48, .04 | −.19 | .13 | −.45, .06 |

| Household size | .002 | .05 | −.10, .10 | .01 | .05 | −.10, .11 | −.001 | .05 | −.10, .10 |

| Health characteristics | |||||||||

| Self-rated physical health | −.27** | .08 | −.43, −.12 | −.27** | .08 | −.42, −.11 | −.28*** | .08 | −.43, −.12 |

| Number of chronic conditions | .06* | .03 | .001, .13 | .06 | .03 | −.001, .12 | .07* | .03 | .01, .13 |

| Functional limitations | −.01 | .02 | −.04, .02 | −.02 | .02 | −.04, .01 | −.02 | .02 | −.04, .01 |

| Pain intensity | .10 | .06 | −.02, .22 | .11 | .06 | −.01, .22 | .09 | .06 | −.03, .21 |

| Stress related to the pandemic | |||||||||

| Worry about COVID-19 infection | .73*** | .06 | .62, .84 | .73*** | .06 | .61, .84 | .71*** | .06 | .59, .82 |

| Financial strain | .16** | .05 | .06, .26 | .17** | .05 | .06, .27 | .17** | .05 | .06, .27 |

| Total stressors | .001 | .04 | −.07, .07 | −.001 | .04 | −.07, .07 | .004 | .04 | −.07, .08 |

| Social resources since the pandemic | |||||||||

| Social contact | −.14* | .06 | −.25, −.02 | −.10 | .06 | −.21, .02 | |||

| Emotional support | .05 | .03 | −.02, .11 | .05 | .03 | −.01, .12 | |||

| Social resources since the pandemic × Age | |||||||||

| Social contact × Age | .02** | .01 | .01, .03 | ||||||

| Emotional support × Age | .01 | .004 | −.002, .01 | ||||||

| Total R2 | .350 | .356 | .367 | ||||||

| Change in R2 | .350*** | .006* | .011** | ||||||

Note. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019. N = 705 adults.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Significant moderating effect of age on the association between frequency of social contact since the COVID-19 pandemic and anxiety symptoms among older adults with chronic conditions. ***p = .001.

Discussion

In this study, we examined how social contact and emotional support during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with anxiety symptoms among adults aged 50 and older with chronic conditions, and whether these links varied by age. We hypothesized that people who reported more frequent social contact and more frequent emotional support would have lower anxiety symptoms, and that these associations would be stronger for older individuals. Overall, the current findings show that these hypotheses were partially supported. More specifically, we found that more frequent social contact was significantly associated with lower anxiety symptoms among younger but not older individuals. Counter to our hypothesis, emotional support was not significantly associated with anxiety symptoms. As a whole, consistent with stress process models of mental health (Pearlin, 1999), these findings underscore the need to consider the role of social resources in mitigating anxiety symptoms among older adults living with chronic conditions during the current pandemic and in future public health crises.

In line with socioemotional selectivity theory (Charles & Carstensen, 2010), we hypothesized that the link between social contact and anxiety would be stronger among older individuals because of their greater focus on maintaining close social ties; however, there may be several reasons for the opposite finding. First, past research has shown that older adults often demonstrate greater resilience, or the ability to cope with difficult situations, during crises due to their past experience in navigating challenging times (Birditt et al., 2020; Carstensen et al., 2020). Hence, social contact may have been a more powerful resource in preserving the mental health of younger individuals who have had relatively less experience with overcoming adversity. Second, younger individuals have reported more life changes (e.g., work routines, school closures) as a result of the pandemic (Birditt et al., 2020) that may have made social contact more central to their mental health and coping. Third, younger individuals typically have more frequent social contact in non-pandemic times than older individuals; therefore, social distancing practices and lockdowns may have had a more significant mental health impact on younger people (Cornwell, 2011). Indeed, relative to older individuals, younger individuals have reported greater pandemic-related stress, loneliness, and perceived social isolation in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic (Beam & Kim, 2020; Birditt et al., 2020; Luchetti et al., 2020; Polenick et al., 2021).

Counter to our hypothesis, individuals who reported more frequent emotional support did not report significantly lower anxiety symptoms. There are several possible reasons for this somewhat counterintuitive finding. Emotional support may have mattered less than social contact for older adults living with chronic conditions during the pandemic because the emphasis on social distancing reduced opportunities for in-person contact. As such, safely maintaining social contact despite pandemic-related barriers may have played a more important role than emotional support in restoring some feelings of normalcy and routine, which in turn helped to mitigate anxiety symptoms. Additionally, measures of emotional support are intangible rather than tangible (Carstensen et al., 2000). This may have made it more difficult for the study participants to accurately recall and report their average level of emotional support versus their social contact since the pandemic began. Future research is needed to gain more nuanced knowledge of the differential impact of social contact and emotional support on anxiety symptoms and other measures of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is important to note that about one-third (33.9%) of the study participants reported anxiety symptoms that met or exceeded the threshold of clinical significance, with clinically significant symptoms reported by 43.9% of those aged 50–64 and 23.6% of those aged 65 and older. These estimates are considerably higher than estimates of anxiety disorder prevalence in both the general population (3.8–4.0%; Baxter et al., 2014a) and among older adults (11.4%; Reynolds et al., 2015). This may in part be specific to our convenience sample of older adults with chronic conditions, which included almost one-quarter (24.8%) of individuals with a self-reported diagnosis of anxiety disorder. Therefore, these findings may not be representative of U.S. adults aged 50 and older who lived with chronic conditions in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the present study indicates the importance of screening for clinically significant anxiety among adults aged 50 and older during the pandemic, perhaps especially for those who live with chronic conditions and may be more worried about COVID-19 infection. Routine clinical care of these individuals should also include the development and use of strategies to manage and cope with anxiety symptoms.

We acknowledge several limitations. First, we cannot determine causal associations in a cross-sectional study. Second, the self-selected convenience sample may introduce bias. Third, participants were mostly women, non-Hispanic White, highly educated, and Michigan residents, and all needed online access. Thus, the findings may not generalize to more representative samples. Fourth, the findings may be particular to 2 to 4 months after initial U.S. social distancing recommendations. Nevertheless, the current findings indicate that increasing social contact may improve well-being among midlife adults with chronic conditions. These findings lay groundwork for future studies to delve more deeply into the implications of social resources for mental health among older adults living with chronic conditions during this pandemic and in subsequent public health crises.

Clinical Implications.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have negative mental health consequences for adults aged 50 and older, including clinically significant anxiety, and social contact may help to mitigate anxiety symptoms.

As a group, older adults were more resilient and may be a resource of support for middle-aged adults and other older adults with clinically significant anxiety symptoms.

Interventions to manage anxiety symptoms during the pandemic among older adults with chronic conditions may benefit from strategies to safely increase social contact, especially for middle-aged adults.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number K01 AG059829 to C.A.P]. This study was also supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number P30 AG015281], the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [grant number UL1TR002240], and the Michigan Center for Urban African American Aging Research.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts with any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

- Bäuerle A, Teufel M, Musche V, Weismüller B, Kohler H, Hetkamp M, Dörrie N, Schweda A, & Skoda E-M (2020). Increased generalized anxiety, depression and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Germany. Journal of Public Health, 42(4), 672–678. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Ferrari AJ, Norman RE, Vos T, & Whiteford HA (2014a). Challenging the myth of an “epidemic” of common mental disorders: trends in the global prevalence of anxiety and depression between 1990 and 2010. Depression and Anxiety, 31(6), 506–516. doi: 10.1002/da.22230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A, Vos T, Scott K, Ferrari A, & Whiteford H (2014b). The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychological Medicine, 44(11), 2363–2374. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713003243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beam CR & Kim AJ (2020). Psychological sequelae of social isolation and loneliness might be a larger problem in young adults than older adults. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S58–S60. doi: 10.1037/tra0000774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Turkelson A, Fingerman KL, Polenick CA, & Oya A (2020). Age differences in COVID-19 related stress, life changes, and social ties during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for psychological well-being. The Gerontologist. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui CN, Peng C, Mutchler JE, & Burr JA (2020). Race and ethnic group disparities in emotional distress among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Gerontologist, 61(2), 262–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, & Nesselroade JR (2000). Emotional experience in everyday life across the life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(4), 644–655. 10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Shavit YZ, & Barnes JT (2020). Age advantages in emotional experience persist even under threat from the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Science, 31(11), 1374–1385. doi: 10.1177/0956797620967261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon PM, Orwoll ES, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Kritchevsky SB, Cummings SR, & Newman A (2020). Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying mitigation efforts on older adults. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 75(9), e123–e125. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caycho-Rodríguez T, Tomás JM, Vilca LW, García CH, Rojas-Jara C, White M, & Peña-Calero BN (2021). Predictors of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in older adults: the role of socio-demographic variables and COVID-19 anxiety. Psychology, Health & Medicine. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1944655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a, April 30). Older adults. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/older-adults.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b, December 29). People with certain medical conditions. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html.

- Charles ST, & Carstensen LL (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 383–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell B (2011). Age trends in daily social contact patterns. Research on Aging, 33(5), 598–631. doi: 10.1177/0164027511409442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Dong L, Wang T, Yuan C, Fu R, Zhang L, Liu B, Zhang M, Yin Y, Qin J, Bouey J, Zhao M, & Li X (2020). Psychological symptoms among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. General Hospital Psychiatry, 67, 144–145. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Zoghby SM, Soltan EM, & Salama HM (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and social support among adult Egyptians. Journal of Community Health, 45(4), 689–695. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00853-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson KG (2020). Coping with being cooped up: Social distancing during COVID-19 among 60+ in the United States. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 44, e81. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2020.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Pitzer LM, Chan W, Birditt KS, Franks MM, & Zarit SH (2011). Who gets what and why: Help middle-aged adults provide to parents and grown children. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 87–98. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdhar R, Srivastava V, & Sethi S (2020). Managing mental health issues among elderly during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Geriatric Care and Research, 7(1), 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, & Löwe B (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchetti M, Lee JH, Aschwanden D, Sesker A, Strickhouser JE, Terracciano A, & Sutin AR (2020). The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. American Psychologist, 75(7), 897–908. doi: 10.1037/amp0000690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, Colasanti M, Ferracuti S, Napoli C, & Roma P (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K, Milham M, Sringaris A, Bromet E, Colcombe S, & Zipunnikov V (2020). The CoRonavIruS Health Impact Survey (CRISIS). Adult Self-Report Baseline Form. [Google Scholar]

- Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A (2020). Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102076. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI (1999). Stress and mental health: A conceptual overview. In Horwitz AV & Scheid TL (Eds.), A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems (pp. 161–175). Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pettinicchio D, Maroto M, Chai L, & Lukk M (2021). Findings from an online survey on the mental health effects of COVID-19 on Canadians with disabilities and chronic health conditions. Disability and Health Journal. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, & McMillan D (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polenick CA, Perbix EA, Salwi SM, Maust DT, Birditt KS, & Brooks JM (2021). Loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults with chronic conditions. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(8), 804–813. doi: 10.1177/0733464821996527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds K, Pietrzak RH, El-Gabalawy R, Mackenzie CS, & Sareen J (2015). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in US older adults: Findings from a nationally representative survey. World Psychiatry, 14(1), 74–81. doi: 10.1002/wps.20193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SMA, Mohammad D, Qureshi MFH, Abbas MZ, & Aleem S (2020). Prevalence, psychological responses and associated correlates of depression, anxiety and stress in a global population, during the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(1), 101–110. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00728-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Bower E, Lutz J, Silva C, Gallegos AM, Podgorski CA, Santos EJ, & Conwell Y (2020). Strategies to promote social connections among older adults during ‘social distancing’ restrictions. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr. (1999). SF-36 Health Survey. In Maruish ME (Ed.). The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (p. 1227–1246). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, Niu J, Yin X, Xie J, & Wang X (2021). Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, & Yang N (2020). The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Medical Science Monitor, 26, e923549. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]