Abstract

Background:

The Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is the largest national pay-for-performance program and the first to afford emergency clinicians unique financial incentives for quality measurement and improvement. With little known regarding its impact on emergency clinicians, we sought to describe participation in the MIPS and examine differences in performance scores and payment adjustments based on reporting affiliation and reporting strategy.

Methods:

We performed a cross-sectional analysis using the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2018 Quality Payment Program (QPP) Experience Report dataset. We categorized emergency clinicians by their reporting affiliation (individual, group, MIPS alternative payment model [APM]), MIPS performance scores, and Medicare Part B payment adjustments. We calculated performance scores for common quality measures contributing to the Quality category score if reported through Qualified Clinical Data Registries (QCDRs) or claims-based reporting strategies.

Results:

In 2018, 59,828 emergency clinicians participated in the MIPS - 1,246 (2.1%) reported as individuals, 43,404 (72.5%) reported as groups, and 15,178 (25.4%) reported within MIPS APMs. Clinicians reporting as individuals earned lower overall MIPS scores (median [interquartile range (IQR)], 30.8 [15.0–48.2] points) than those reporting within groups (median [IQR], 88.4 [49.3–100.0]) and MIPS APMs (median [IQR], 100.0 [100.0–100.0]) (p <0.001), and more frequently incurred penalties with a negative payment adjustment. Emergency clinicians had higher measure scores if reporting QCDR or QPP non-EM-Specialty Set measures.

Conclusions:

Emergency clinician participation in national value-based programs is common, with one in four participating through MIPS APMs. Those employing specific strategies such as QCDR- and group-reporting received the highest MIPS scores and payment adjustments, emphasizing the role that reporting strategy and affiliation play in the quality of care.

Keywords: Merit-based Incentive Payment System, quality measurement, qualified clinical data registry, payment, population health

Introduction

The 2006 Tax Relief and Health Care Act authorized the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to establish the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), an early federal foray into physician pay-for-performance.1 The impact of this program on emergency care value was limited due to the small amount of payment at risk, the paucity of emergency medicine (EM)-specific quality measures, and the lack of connection between Quality and Cost categories as elements determining payment.2 In response, Congress passed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), therein creating the Quality Payment Program (QPP).3,4 The QPP was designed to promote the transition from fee-for-service into value-based and/or quality-adjusted payments specifically through a track called the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).4 The MIPS arm of the QPP started in 2017 and was designed to measure clinicians across four key performance categories intended to drive value: Quality, Promoting Interoperability, Improvement Activities, and Cost. Based on quality measure performance in these four categories, points from a given performance year are combined to produce a final overall score. Starting in the 2020 performance year, the penalty for not meeting MIPS requirements could be as high as 9% of Medicare Part B reimbursements for typical EM groups, potentially representing over $200,000 annually for an 80,000 visit/year emergency department (ED).5–8

In response to CMS quality programs and incentives, medical specialty societies, healthcare data companies, and collaborating clinicians have developed CMS-approved qualified clinical data registries (QCDRs) to serve as a reporting strategy to the MIPS. QCDRs collate data streams (electronic health records, administrative claims, revenue cycle) and facilitate quality measure reporting to CMS using newly developed and validated specialty-specific measures beyond the available limited claims-based quality reporting strategies.9–11 Within EM, two prominent, fee-based QCDRs include the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Clinical Emergency Data Registry (CEDR) and the Vituity Emergency-Clinical Performance Registry (E-CPR).12,13 If not reporting on the approximately 25 measures within one of those available QCDRs, EM clinicians in the 2018 performance year could use claims-based reporting strategies to report on the 14 measures within the QPP EM Specialty Set or the 270 measures captured within the broader QPP non-Specialty Set.9

With the initiation of the MIPS alongside many other federal efforts to transform payment, a recent report from the Department of Health and Human Services identified a goal that 50% of health care payments to traditional Medicare would be within two-sided risk alternative payment models (APMs) by 2022, despite only 18% of payments identified as having met that target in 2019.14–16 APMs are a payment approach to provide high-quality and cost-efficient care, and can apply to a specific clinical condition, a care episode, or a population such as patients seeking emergency care. Most efforts to transition clinicians away from fee-for-service payments have focused on global payment models or on clinicians paid for a bundle of care, such as joint replacement models for orthopedic surgeons,17,18 with little known about emergency clinician engagement or performance in this transition towards increased payment risk. A recent report of 377 EDs identified little EM participation, with only 9.2% of EDs participating in a federal APM and 5.0% participating in a commercial APM.19 A deeper understanding of how emergency clinicians perform in the MIPS is important to guide policy and practice.

During the inaugural 2017 performance year, over 1 million eligible clinicians across all specialties participated in the MIPS with 93% earning a positive or exceptional payment adjustment.20 Studying the 2018 MIPS performance year offers several key benefits, including the incorporation of the Cost category absent in the 2017 MIPS, as well as increased performance thresholds to improve payment adjustment distribution. A recent analysis of otolaryngologists found that clinicians reporting via APMs received payment bonuses for exceptional performance more commonly than those with reporting affiliations of groups or individuals.21 Despite substantially more consolidation in EM, a knowledge gap exists regarding the clinician-level MIPS performance and subsequent payment adjustments in this new national pay-for-performance program. While measure reporting within the Quality category represents the most heavily-weighted for clinician payment in the MIPS, little is known about the impact of newer EM-specific quality measures or reporting strategies, such as QCDRs, on performance scores and payment adjustments.

Therefore, we sought to characterize emergency clinician participation and performance in the MIPS. Specifically, we describe emergency clinician participation within APMs and examine organizational factors associated with MIPS performance scores and payment adjustments.

Methods

Study Design

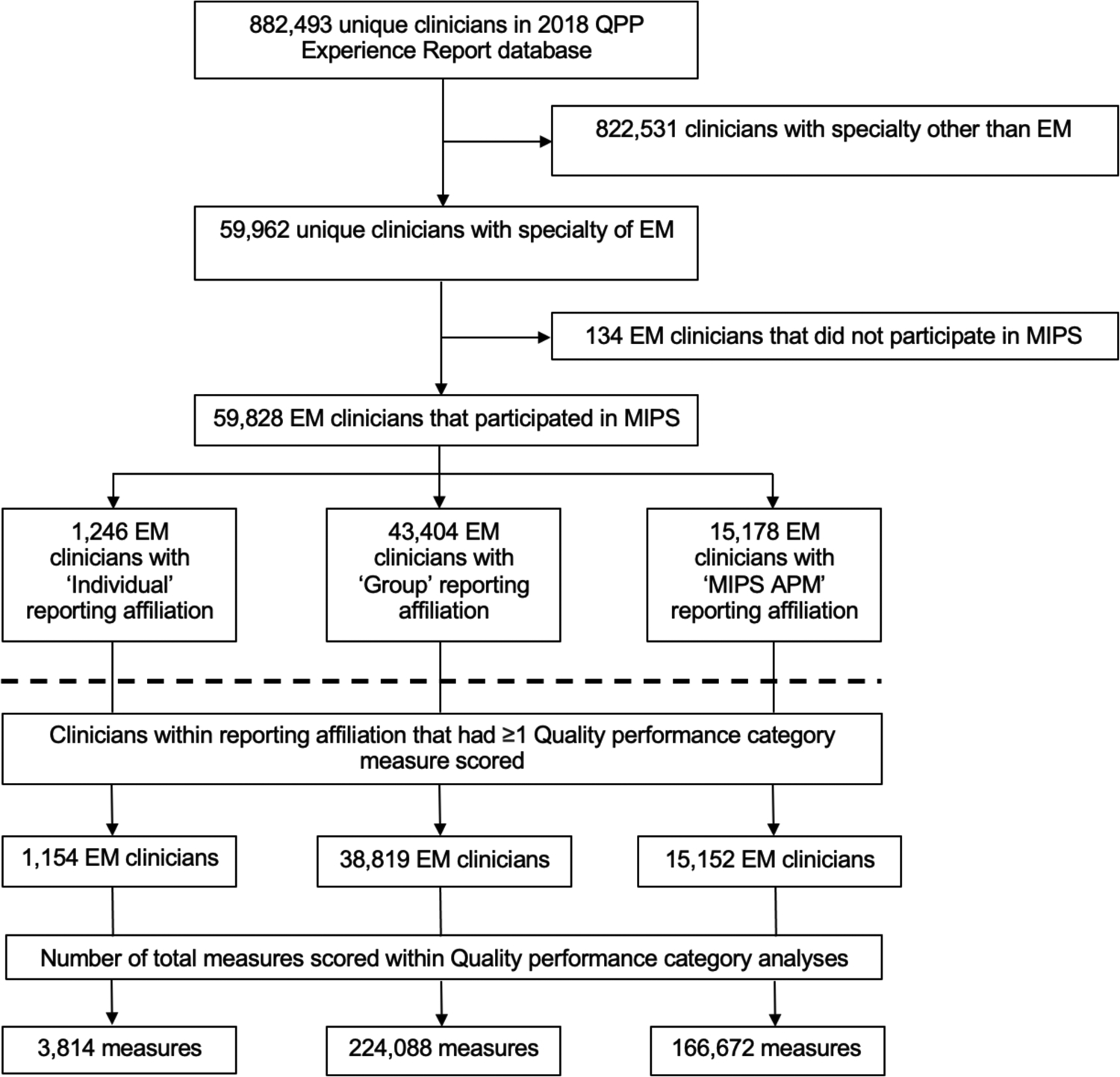

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of EM clinician MIPS performance in the 2018 performance year. Emergency clinicians, including physicians and non-physician practitioners, were identified using the primary specialty listed in the publicly available 2018 Quality Payment Program (QPP) Experience Report dataset as of November 1, 2020 (Figure 1).22

Figure 1.

Analytic sample for emergency clinicians and quality measures

Abbreviations: APM, alternative payment model; EM, emergency medicine; MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System

Note: Table 1, Table 2, and Figure 2 include the derived analytic sample above the dashed line. Table 3, assessing quality measure scoring within the Quality category, includes the derived analytic sample below the dashed line.

MIPS Eligibility Criteria

To avoid a penalty, clinicians were required to participate in the MIPS if they: 1) were a MIPS-eligible clinician type, 2) exceeded the low volume threshold, and 3) were not otherwise excluded.23 MIPS-eligible clinician types are defined annually by CMS through rulemaking. In 2018, MIPS-eligible clinicians met the low volume threshold and were required to participate in MIPS if they billed more than $90,000 in Medicare Part B covered professional services and provided care for more than 200 Medicare Part B beneficiaries in two distinct annual determination periods. Clinicians may be excluded from MIPS reporting if they participated within the second arm of the QPP through an Advanced APM. Additional exclusions include enrollment in Medicare for the first time in 2018 or participation in a Medicare Advantage Qualifying Payment Arrangement Incentive.24 We categorized emergency clinicians by their MIPS reporting affiliation (individual, group, MIPS APM) self-selected upon submission and listed within the dataset. We also extracted “special status” designations for emergency clinicians.24 These designations determine whether certain rules affect the number of required reported measures, activities, or bonus points for a reporting clinician. In 2018, extracted “special status” designations included small practice, rural practice, and health professional shortage area (HPSA).

Methods of Measurement

In 2018, the CMS calculated overall MIPS scores by applying the following performance category weights unless the clinician qualified for reweighting: Quality – 50%, Cost – 10%, Improvement Activities – 15%, Promoting Interoperability – 25%.5 The Quality category is the most important for emergency clinicians because most are exempt from the Promoting Interoperability category, with performance reweighted to the Quality category, which then accounts for over 75% of the overall MIPS score. Consistent with CMS methodology and based on their 2018 overall MIPS score, we categorized clinicians as having received a payment adjustment – exceptional (overall MIPS score 70–100), positive (overall MIPS score 15.01–69.99), neutral (overall MIPS score 15.00), and negative (overall MIPS score 0–14.99) – during the 2018 performance year.5,23

Within the MIPS Quality category, a few technical points merit clarification. Clinicians must report and are scored on 6 measures, and these may be from the QPP EM Specialty Set, QPP non-Specialty Set, or QCDRs. The QPP EM Specialty Set from the 2018 performance year included 14 measures (e.g. QPP 254 – Ultrasound determination of pregnancy location for pregnant patients with abdominal pain) that are intended to be more relevant to EM practice.9 The QPP non-Specialty Set included the remaining 270 quality measures (e.g. QPP 111 – Pneumococcal vaccination status for older adults) that clinicians could choose to report to CMS. If a group or individual emergency clinician reported more than 6 measures, then CMS methodology notes that the 6 highest scoring measures contribute towards the Quality category performance score. If fewer than 6 measures were reported, a score of 0 was assigned towards each non-reported measure.5 Additional bonus points were available within the Quality category if reporting additional outcome, patient experience, or high-priority measures beyond the one required, as well as if meeting end-to-end electronic reporting criteria (e.g. qualified registry, QCDR).25 Based on model requirements, emergency clinicians reporting within MIPS APMs could have had more than 6 measures reported and scored within the Quality category.24 Due to the importance of the Quality category, we identified common quality measures contributing to the category’s score, particularly assessing measures reported by >1% of emergency clinicians.

Statistical Analysis

We performed descriptive statistical analyses of clinician characteristics, MIPS reporting affiliations, MIPS performance overall and category scores, and payment adjustments. Because distributions of MIPS performance scores were not normally distributed, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test and the post-hoc Dunn test with Bonferroni adjustments for multiple comparisons to compare medians across reporting affiliations. Given its large contribution to the overall MIPS score, we also examined the Quality category by presenting decile measure scores for each quality measure if scored by >1% of EM clinicians. All analyses were performed in Stata, version 16.0 (StataCorp) between November 2, 2020 and December 8, 2020. The institutional review board deemed this study exempt, as this research used a public data source without patient health information.

Results

During the 2018 performance year, 59,828 emergency clinicians participated in the MIPS. Of those, 1,246 (2.1%) emergency clinicians reported data as individuals, 43,404 (72.5%) reported data as groups, and 15,178 (25.4%) reported data as MIPS APMs (Figure 1). A greater proportion of emergency clinicians reporting as individuals practiced in small size practices, urban designations, and HPSAs, achieving “special status” designations, when compared to emergency clinicians reporting within groups and MIPS APMs.

Emergency clinicians reporting as individuals earned lower overall scores (median [interquartile range (IQR)], 30.8 [15.0–48.2] points) than those reporting as groups (median [IQR], 88.4 [49.3–100.0] points) and MIPS APMs (median [IQR], 100.0 [100.0–100.0] points) (p <0.001). The difference was largely driven by scores within the Quality category – emergency clinicians reporting as individuals earned lower Quality category scores (median [IQR], 21.7 [8.3–40.0] points) than those reporting as groups (median [IQR], 79.7 [30.0–100.0] points) and MIPS APMs (median [IQR], 100.0 [98.7–100.0] points) (p <0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2 –

Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) category and overall performance scores, stratified by reporting affiliation

| Affiliation | N | Median (IQR) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | Promoting Interoperability | Improvement Activities | Cost | Overall | ||

| Individual | 1,246 | 21.7 (8.3–40.0) |

0 (0–0) |

0 (0–40.0) |

0 (0–0) |

30.8 (15.0–48.2) |

| Group | 43,404 | 79.7 (30.0–100.0) |

0 (0–0) |

40.0 (40.0–40.0) |

87.3 (0–100.0) |

88.4 (49.3–100.0) |

| MIPS APM | 15,178 | 100.0 (98.7–100.0) |

100.0 (100.0–100.0) |

40.0 (40.0–40.0) |

0 (0–0) |

100.0 (100.0–100.0) |

Abbreviations: APM, alternative payment model; IQR, interquartile range

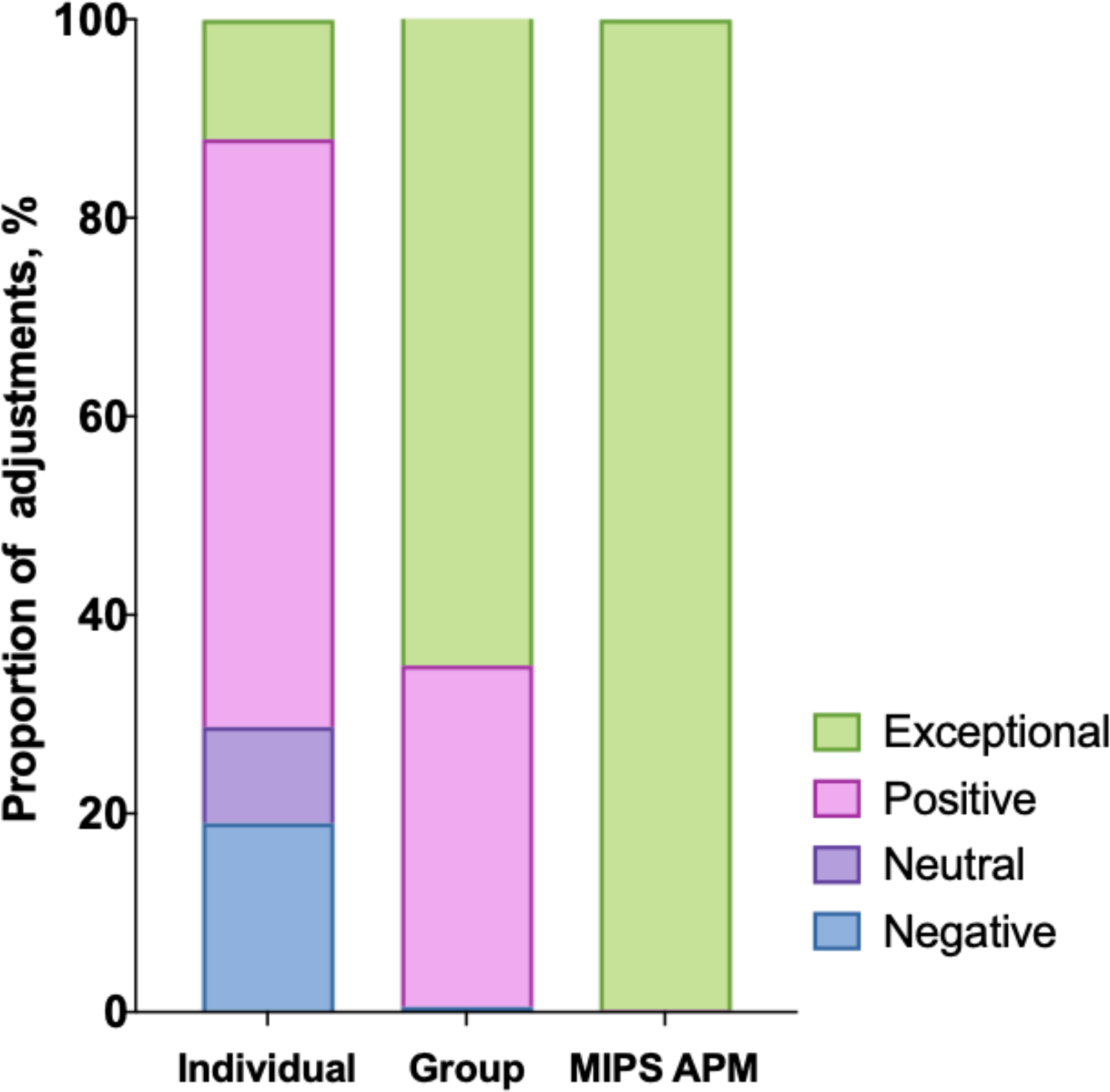

Almost three-quarters (43,560 of 59,828 [72.8%]) of emergency clinicians participating in the MIPS received bonuses for exceptional performance. The remainder received a positive payment adjustment (15,693 of 59,828 [26.2%]), a neutral payment adjustment (123 of 59,828 [0.2%], or a negative payment adjustment (452 of 59,828 [0.8%]) (Supplemental Table 1). Payment adjustments also varied by reporting affiliation (Figure 2). Of those emergency clinicians reporting as individuals, 150 (12.0%) earned bonuses for exceptional performance and 237 (19.0%) incurred penalties with a negative payment adjustment. Of those emergency clinicians reporting as a group, 28,257 (65.1%) earned bonuses for exceptional performance and 215 (0.5%) incurred penalties with a negative payment adjustment. Of those emergency clinicians reporting within MIPS APMs, 15,153 (99.8%) earned bonuses for exceptional performance and no clinicians incurred penalties (Figure 2, Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 2.

Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) reporting affiliation and payment adjustments for emergency clinicians

Abbreviations: APM, alternative payment model; MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System

Within the Quality category, measures were reported by 1,154 individual clinicians, 38,819 group clinicians, and 15,152 clinicians within MIPS APMs. Quality measure performance differed between reporting strategies within the QPP EM Specialty Set, QPP non-Specialty Set, and QCDRs (Table 3, Supplemental Table 2). Of the 14 quality measures within the 2018 QPP EM Specialty Set, 12 were scored by more than 1% of EM clinicians. QPP 091 (Acute otitis externa: topical therapy) was the most frequently reported measure within this group, with scores ranging from 0 to 10.0, with a median of 9.0. Of the broader QPP non-Specialty Set, 31 measures were scored by more than 1% of emergency clinicians. Within Table 3, we show the 9 most commonly scored for the sake of brevity. QPP 204 (Ischemic vascular disease: use of aspirin or another antiplatelet) was the most frequently reported measure within this group, with scores ranging from 9.0 to 10.0, with a median of 10.0. Of the 39 available QCDR measures, 11 were scored by more than 1% of emergency clinicians. ACEP 40 (median time from ED arrival to ED departure for discharged ED patients for pediatric patients) was the most frequently reported measure within this group, with scores ranging from 0 to 10.0, with a median of 8.1. Grouped by deciles, emergency clinicians scoring Quality category measures from QCDRs and the QPP non-Specialty Set had greater individual measure scores than measures from the QPP EM Specialty Set.

Table 3.

Common measures scored by decile of performance for emergency clinicians within the Quality category of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program, stratified by reporting strategy

| Decile | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure ID | Clinicians, N (%) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| QPP - EM Specialty Set | QPP 091 | 15,159 (27.5) | 0.0 | 3.0 | 6.6 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 9.6 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| QPP 066 | 14,598 (26.5) | 0.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 8.8 | 9.8 | |

| QPP 093 | 13,502 (24.5) | 0.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 5.4 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 331 | 12,622 (22.9) | 0.0 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 8.5 | |

| QPP 333 | 12,079 (21.9) | 0.0 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 415 | 11,584 (21.0) | 0.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 7.2 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 116 | 8,191 (14.9) | 0.0 | 3.0 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 6.9 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 416 | 6,749 (12.2) | 0.0 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 6.0 | 6.9 | 8.6 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 317 | 5,224 (9.5) | 0.0 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 8.3 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 332 | 4,590 (8.3) | 0.0 | 6.6 | 8.9 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 254 | 4,456 (8.1) | 0.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 187 | 3,965 (7.2) | 0.0 | 5.5 | 7.0 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| QPP-non Specialty Set | QPP 204 | 20,272 (36.8) | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| QPP 111 | 19,261 (34.9) | 0.0 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 318 | 18,066 (32.8) | 0.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 9.8 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 128 | 17,937 (32.5) | 0.0 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 10.0 | |

| QPP 236 | 17,591 (31.9) | 0.0 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 9.1 | |

| QPP 112 | 17,413 (31.6) | 0.0 | 7.2 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 9.1 | 9.3 | |

| QPP 110 | 17,260 (31.3) | 0.0 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 9.1 | 9.5 | |

| QPP 134 | 17,222 (31.2) | 0.0 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 9.8 | |

| QPP 113 | 16,373 (29.7) | 0.0 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 8.9 | |

| QCDR | ACEP40 | 4,296 (7.8) | 0.0 | 4.7 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 9.2 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| ACEP32 | 3,825 (6.9) | 0.0 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 8.0 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| ACEP21 | 2,835 (5.1) | 0.0 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 9.6 | |

| ACEP24 | 2,700 (4.9) | 0.0 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| ACEP25 | 2,372 (4.3) | 0.0 | 7.9 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| ECPR39 | 1,705 (3.1) | 3.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| ACEP48 | 1,441 (2.6) | 0.0 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 9.7 | 10.0 | |

| ECPR40 | 1,431 (2.6) | 3.0 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.5 | |

| ACEP30 | 862 (1.6) | 0.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 7.3 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 10.0 | |

| ACEP29 | 712 (1.3) | 0.0 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 10.0 | |

| ACEP19 | 701 (1.3) | 0.0 | 4.1 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 10.0 | |

Abbreviations: ACEP, American College of Emergency Physicians; ECPR, Emergency-Clinical Performance Registry; QCDR, Qualified Clinical Data Registry; QPP, Quality Payment Program

Note: Serving as the denominator for % clinicians reporting, 55,125 clinicians had ≥1 measure scored within the Quality category. The 2018 QPP EM Specialty Set included 14 measures. Shown above are the 12 measures that contributed to >1% of EM clinicians MIPS Quality category scores. While 31 total QPP-non Specialty Set measures contributed to >1% of EM clinicians MIPS Quality performance category scores, we show the top 9 most commonly reported for brevity. Available QCDRs included 38 possible measures. Shown above are the 11 QCDR measures that contributed to >1% of EM clinicians MIPS Quality category scores. The measure ID with associated title can be seen in Supplemental Table 2. Decile boxes show the distribution of scores across a specific measure. Decile 1 includes the lowest 10% of scores by EM clinicians (0–10th percentile), while Decile 10 includes the highest 10% of scores by EM clinicians (90–100th percentile). The value reported within the box is the lowest measure score within that specific 10-percentile range. For example, 15,159 (27.5%) EM clinicians had the QPP 091 measure scored towards their MIPS Quality category score. The minimum score was 0.0, denoted by Decile 1; the maximum score was 10.0, denoted by Decile 10 (extrapolated because the 90th percentile score is 10.0 noted by this box); and the median score was 9.0, denoted by Decile 6 (lowest measure score between 50–60th percentile).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional analysis of emergency clinicians, we evaluated 2018 MIPS performance scores and associated payment adjustments based on clinician reporting affiliation and reporting strategy. Our study has three major findings. First, emergency clinicians reporting as individuals earned lower overall MIPS performance scores than those reporting within groups or MIPS APMs with the difference largely driven by scores within the Quality category. Second, payment adjustments varied by reporting affiliation, with one in four emergency clinicians reporting within MIPS APMs and virtually all of those clinicians received an exceptional payment adjustment. Conversely, almost 20% of emergency clinicians reporting as individuals received a negative payment adjustment. Third, many emergency clinicians reported Quality category measures within QCDRs and used the QPP non-Specialty Set, with the lowest measure scores identified for measures within the QPP EM Specialty Set.

Our work builds upon the literature in a number of ways. MIPS performance has been assessed for otolaryngologists,21 dermatologists,26 ophthalmologists,27 and radiologists28 but to our knowledge, this is the first study addressing MIPS performance by emergency clinicians. Our findings suggest that over 99% of emergency clinicians received either a positive or exceptional payment adjustment, reflecting better performance than observed for these other specialties. This study is also the first to assess overall MIPS scores with the full complement of performance categories – including Cost – since its incorporation in the 2018 performance year. Furthermore, the increased use of QCDRs for quality reporting has offered clinicians measures that are clinically relevant and evidence-based, with this work being the first to calculate QCDR measure scores for emergency clinicians reporting in national pay-for-performance programs.

Our findings also have several policy implications. First, in agreement with prior evaluations,29 we believe that CMS should consider strategies to make clinician performance a more normal and non-skewed distribution to allow for greater identification of practice variation and opportunities for meaningful improvement. While only a small proportion of emergency clinicians received a negative payment adjustment in the 2018 performance year, the financial incentive for those receiving positive and exceptional payment adjustments is attenuated due to the budget neutrality requirement of the MIPS.30 Performance thresholds to avoid a negative payment adjustment will increase in the coming years, with an overall MIPS performance score of 45 required to avoid a negative payment adjustment in the 2020 performance year, compared to a score of 15 in the 2018 performance year. Globally, the MIPS follows a zero-sum game, suggesting that upward bonuses require other clinicians to be penalized.31 Within the 2018 performance year analyzed, payment adjustments could theoretically range from −5% (penalty) to 5% (bonus). However, in reality, payment adjustments only ranged from −5% to +1.7% given the statutory requirement for the sum of penalties and bonuses to be budget-neutral. For the typical EM group covering an 80,000 visit/year ED introduced earlier, an estimated possible 5% penalty reached upwards of $120,000, while the potential 1.7% bonus in the 2018 performance year was only about $40,000.8 With many clinicians performing above the thresholds set, CMS has also allotted an additional $500 million in bonus payments for exceptional-performing clinicians in this program to increase incentives.32 As the performance thresholds increase, future analyses comparing emergency clinicians to other specialties will be valuable in identifying specialties that are more readily adapting to national pay-for-performance programs. In this analysis, emergency clinicians reporting as individuals were more likely than clinicians within groups or MIPS APMs to be penalized with a negative payment adjustment. This may be a result of decreased technological infrastructure available to these clinicians as suggested by prior literature,33 and if evident, could lead to greater disparities in payment adjustment as performance thresholds increase.

Second, CMS should consider the array of quality measures reported by EM clinicians and whether they are clinically relevant. There exists little ability to identify meaningful variation in emergency care given that the three most common measures reported overall by emergency clinicians in the 2018 performance year were: 1) QPP 204 - Ischemic vascular disease: use of aspirin or another antiplatelet agent, 2) QPP 111 - Pneumococcal vaccination status for older adults, and 3) QPP 318 - Falls: screening for future fall risk. Reporting of quality measures with low clinical relevance results in uninformative data that mimics programs predating the MIPS. Currently, the myriad measures available to emergency clinicians prevents meaningful comparisons and also offers the potential for increased ‘performance’ scores, and thereby payment adjustments, without true improvement in quality. Going forward, quality measures should be prioritized that assess the clinical care of undifferentiated high-risk conditions (e.g. abdominal pain, chest pain), creating alignment with the ACEP Acute Unscheduled Care Model. Future iterations of emergency care value-based payment will also depend upon digital quality measures (captured directly from electronic medical records, registries, or health information exchanges) and a linkage between cost and quality measures.34,35

One solution to the lack of relevance of many reported EM measures is the broader adoption of QCDRs and development of quality measures focusing on clinically meaningful patient outcomes that are able to target performance variation. The creation of new quality measures, often led by specialty societies, requires significant effort and resources.36 Future requirements of QCDRs will undoubtedly increase as CMS continues to develop a framework linking Quality and Cost.37 Specialties, their associated societies, and respective QCDRs are increasingly strained, with limited resources to develop, test and validate meaningful measures. Going forward, this may perpetuate and even increase the likelihood of reporting on clinically irrelevant quality measures.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we are limited to define the analytic sample as ‘emergency clinicians’, and based on the dataset are unable to further characterize differences between physicians and non-physicians. On a related note, the specialty description within the dataset is an identifier corresponding to the type of service that the clinician submitted most of their Physician Fee Schedule Part B claims, therefore appropriately including emergency clinicians not only based on residency training or Board Certification status. Second, the present analysis is limited to 2018 MIPS performance scores, which may lack generalizability as the program evolves. Future work should evaluate changes in performance over time. Finally, this study does not include patient-level data to assess the quality or outcomes of emergency care provided.

Conclusion

Emergency clinician participation in national value-based programs is common, with one in four participating through MIPS APMs. Those employing specific reporting strategies such as QCDR- and group-reporting received the highest MIPS scores and payment adjustments. Many clinicians report on quality measures that are of questionable relevance to emergency medicine. These findings emphasize the need for clinically relevant EM-specific measures that improve the quality of care and reliably identify practice variation.

Supplementary Material

Table 1 –

Clinician characteristics associated with MIPS reporting affiliation

| Total (N = 59,828) |

Individual (n = 1,246) |

Group (n = 43,404) |

MIPS APM (n = 15,178) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (median, IQR)a | 89 (39–284) | 45 (20–93) | 83 (37–251) | 127 (51–440) |

| Small size, %b | 4.5 | 17.4 | 3.9 | 5.1 |

| Rural designation, %c | 18.1 | 13.6 | 18.1 | 18.5 |

| Practicing in HPSA, %d | 25.9 | 28.4 | 27.4 | 21.5 |

Abbreviations: APM, alternative payment model; HPSA, Health Professional Shortage Area; IQR, interquartile range; MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System

Note:

Count of clinicians associated with the Taxpayer Identification Number (TIN)

Dichotomized follows Medicare rules as small (15 or fewer clinicians)

Practices in a zip code designated as rural using data from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

Practices in a designation that indicates health care provider shortages in primary care, dental health, or mental health using data from the HRSA

Financial Support:

Dr. Gettel is supported by the Yale National Clinician Scholars Program and by CTSA Grant Number TL1 TR00864 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Venkatesh is supported in part by the American Board of Emergency Medicine National Academy of Medicine Anniversary fellowship and previously by the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation grant KL2 TR000140 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science of the NIH. Dr. Griffey and Kocher are supported by grant R01 HS027811-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. Dr. Griffey is also supported by K12 HL137942 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and #3676 from the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital. Dr. Kocher is also supported by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

CTB, MAG, RTG, AM, and AKV serve on the Clinical Emergency Data Registry (CEDR) Committee within the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP). CJG, MAG, KEK, AM, JDS, RTG, and AKV serve on the Quality & Patient Safety Committee within ACEP. KEK and AZA serve on the Emergency Care Quality Measures Consortium. KEK also reports a grant from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network to support a statewide emergency department quality improvement network. AKV also receives support for contracted work from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop hospital and healthcare outcome and efficiency quality measures and rating systems.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations:

This research was selected for virtual presentation at the May 2021 Society for Academic Emergency Medicine annual meeting.

References

- 1.Dowd B, Li C, Swenson T, Coulam R, Levy J. Medicare’s Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS): quality measurement and beneficiary attribution. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev 2014;4(2):eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsch JA, Leslie-Mazwi TM, Nicola GN, et al. PQRS and the MACRA: value-based payments have moved from concept to reality. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37(12):2195–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, HHS. Medicare program; Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and Alternative Payment Model (APM) incentive under the physician fee schedule, and criteria for physician-focused payment models. Final rule with comment period. Fed Regist 2016;81(214):77008–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program – MIPS Overview. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/overview. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program – Resource Library. https://qpp.cms.gov/about/resource-library. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 6.Health Catalyst. The complete guide to MIPS 2021: scoring, payment adjustments, measures, and reporting frameworks. https://www.healthcatalyst.com/insights/mips-2021-complete-guide/. Accessed June 21, 2021.

- 7.Granovsky M, McKenzie D. CMS proposed rule includes 2020 emergency physician compensation increase. https://www.acepnow.com/article/cms-proposed-rule-includes-2020-emergency-physician-compensation-increase/3/?singlepage=1. Accessed January 26, 2021.

- 8.Granovsky M 2019. Merit-based Incentive Payment System. https://www.mcep.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/18-Granovsky-Quality-Payment-Updates-MIPS.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2021.

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program – Explore Measures & Activities. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/explore-measures?tab=qualityMeasures&py=2018. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. A brief overview of Qualified Clinical Data Registries (QCDRs). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/A-Brief-Overview-of-Qualified-Clinical-Data-Registries.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2021.

- 11.American Medical Association. Qualified Clinical Data Registries (QCDRs). https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-11/qcdr-update-2017-2019.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2021.

- 12.American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical Emergency Data Registry. https://www.acep.org/cedr/. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 13.Vituity. E-CPR QCDR and MedAmerica QDR. https://www.vituity.com/services/emergency-medicine/e-cpr-qcdr/. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 14.McClellan MB, Smith MD, Buckingham T. A roadmap for driving high performance in alternative payment models. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190328.638435/full/. Accessed January 24, 2021.

- 15.Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network. APM Measurement Effort. https://hcp-lan.org/apm-measurement-effort/. Accessed January 8, 2021.

- 16.Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals – HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med 2015;372(10):897–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berdahl CT, Easterlin MC, Ryan G, Needleman J, Nuckols TK. Primary care physicians in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS): a qualitative investigation of participants’ experiences, self-reported practice changes, and suggestions for program administrators. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2275–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharyya T, Freiberg AA, Mehta P, Katz JN, Ferris T. Measuring the report card: the validity of pay-for-performance metrics in orthopedic surgery. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(2):526–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berdahl CT, Schuur JD, Rothenberg C, et al. Practice structure and quality improvement activities among emergency departments in the Emergency Quality (E-QUAL) Network. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2020;1(5):839–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2017. Quality Payment Program performance year data. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/276/2017%20QPP%20Performance%20Data%20Infographic%20Final.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2021.

- 21.Xiao R, Rathi VK, Kondamuri N, et al. Otolaryngologist performance in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System in 2017. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;146(7):639–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2018. QPP Experience Report PUF. https://data.cms.gov/dataset/2018-QPP-Experience-Report-PUF/r92e-pxsd. Accessed November 1, 2020.

- 23.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program (QPP) participation in 2018: results at-a-glance. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/586/2018%20QPP%20Participation%20Results%20Infographic.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2021.

- 24.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program – MIPS Alternative Payment Models (APMs). https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/mips-apms. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2018 MIPS Scoring Guide. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/179/2018%20MIPS%20Scoring%20Guide_Final.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2021.

- 26.Gronbeck C, Feng PW, Feng H. Participation and performance of dermatologists in the 2017 Merit-based Incentive Payment System. JAMA Dermatol 2020;156(4):466–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng PW, Gronbeck C, Chen EM, Teng CC. Ophthalmologists in the first year of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System. Ophthalmology 2020;S0161–6420(20)30515–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenkrantz AB, Duszak R, Golding LP, Nicola GN. The Alternative Payment Model pathway to radiologists’ success in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System. J Am Coll Radiol 2020;17(4):525–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apathy NC, Everson J. High rates of partial participation in the first year of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39(9):1513–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navathe AS, Dinh CT, Chen A, Liao JM. Findings and implications from MIPS year 1 performance data. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190117.305369/full/. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 31.Introcaso D The many problems with Medicare’s MIPS exclusion thresholds. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170803.061372/full/. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2020 MIPS Payment Adjustment Fact Sheet. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/659/2020%20Payment%20Adjustment%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2021.

- 33.Johnston KJ, Wiemken TL, Hockenberry JM, Figueroa JF, Joynt Maddox KE. Association of clinician health system affiliation with outpatient performance ratings in the Medicare Merit-based Incentive Payment System. JAMA 2020;324(10):984–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis J Paving the way towards value-based care: ACEP submits an MIPS Value Pathway (MVP) proposal to CMS. https://www.acep.org/federal-advocacy/federal-advocacy-overview/regs--eggs/regs--eggs-articles/regs---eggs---february-25-2021/. Accessed March 1, 2021.

- 35.Gettel CJ, Ling SM, Wild RE, Venkatesh AK, Duseja R. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services MIPS Value Pathways: Opportunities for emergency clinicians to turn policy into practice. Ann Emerg Med. In-press (accepted for publication). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golding LP, Nicola GN, Duszak R, Rosenkrantz AB. The quality measures crunch: How CMS topped out scoring and removal policies disproportionately disadvantage radiologists. J Am Coll Radiol 2020;17(1 Pt B):110–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs). https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/mips-value-pathways. Accessed December 3, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.