Abstract

Background.

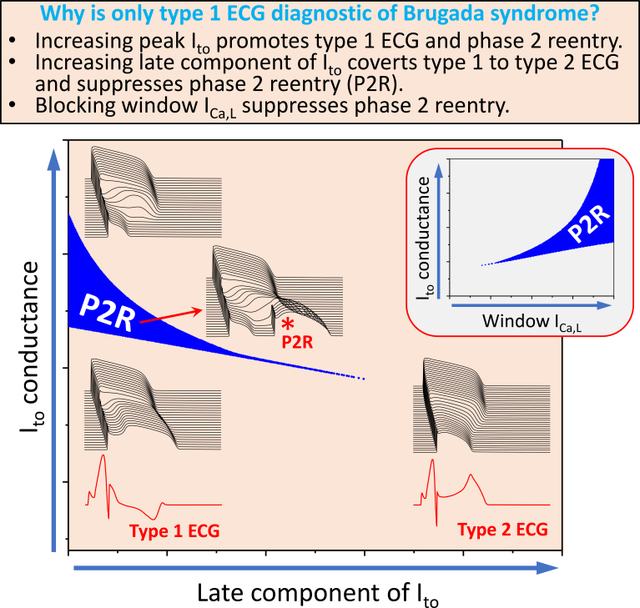

Three types of characteristic ST-segment elevation are associated with Brugada syndrome (BrS) but only type 1 is diagnostic. Why only type 1 electrocardiogram (ECG) is diagnostic remains unanswered.

Methods.

Computer simulations were carried out in single cells, one-dimensional cables, and two-dimensional tissues to investigate the effects of the peak and late components of the transient outward potassium current (Ito), sodium current (INa), and L-type calcium current (ICa,L) as well as other potassium currents on the genesis of ECG morphologies and phase 2 reentry (P2R).

Results.

Although a sufficiently large peak Ito was required to result in the type 1 ECG pattern and P2R, increasing the late component of Ito converted type 1 ECG to type 2 ECG and suppressed P2R. Increasing the peak Ito promoted spiral wave breakup, potentiating the transition from tachycardia to fibrillation, but increasing the late Ito prevented spiral wave breakup by flattening the action potential duration restitution and preventing P2R. A sufficiently large ICa,L conductance was needed for P2R to occur, but once above the critical conductance, blocking ICa,L promoted P2R. However, selectively blocking the window and late components of ICa,L suppressed P2R, countering the effect of the late Ito. Blocking either the peak or late components of INa promoted P2R, with the late INa blockade having the larger effect. As expected, increasing other potassium currents potentiated P2R, with IK-ATP exhibiting a larger effect than IKr and IKs.

Conclusions.

The peak Ito promotes type 1 ECG and P2R, whereas the late Ito converts type 1 ECG to type 2 ECG and suppresses P2R. Blocking the peak ICa,L and either the peak or the late INa promotes P2R whereas blocking the window and late ICa,L suppresses P2R. These results provide important insights into the mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis and potential therapeutic targets for treatment of BrS.

Keywords: Brugada syndrome, type 1 ECG, phase 2 reentry, late current, computer simulation

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an inherited heart disease characterized by J-point and ST-segment elevation in surface ECG and associated with a high risk of sudden cardiac death 1–4. As described in current consensus statements 5–7, there are three types of characteristic ECGs associated with BrS (see Fig.I in Data Supplement). Type 1 is characterized by coved ST-segment elevation >2 mm in leads V1-V3 with a negative T-wave, type 2 by a saddleback ST-segment elevation >2 mm, and type 3 with either coved or saddleback ST-segment ST elevation <1 mm. In all three types of ECGs, the J-point is elevated. However, only type 1 is diagnostic of BrS 5–7. Patients exhibiting type 2 or type 3 ECGs can sometimes be converted to type 1 by provocative drugs such Na+ channel blockers, but still have very low risk of arrhythmias 7, 8.

The cellular mechanisms of coved and saddleback ECGs have been linked to the spike-and-dome action potential (AP) morphology caused by the transient outward K+ current (Ito) by Antzelevitch and coworkers 9, who also showed that the spike-and-dome AP morphology promotes phase 2 reentry (P2R) initiating ventricular fibrillation 10–12. However, why only type 1 ECGs are diagnostic of BrS and confer a high risk of sudden cardiac death remains unanswered. In this study, we used computer models to investigate the mechanisms underlying the three characteristic ECG morphologies and their links to arrhythmogenesis. We carried out simulations in single cells, one-dimensional (1D) cables, and two-dimensional (2D) tissues to investigate the effects of the peak and late components of Ito, the L-type calcium current (ICa,L) and the sodium current (INa). We also investigated the effects of other K+ currents, i.e., the rapid (IKr) and slow (IKs) components of the delayed rectifier K+ current, and the ATP-sensitive K+ current (IK-ATP). We show that while a sufficiently large peak Ito is required to initiate phase 2 reentry (P2R), increasing the late component of Ito converts type 1 ECG to type 2 ECG and suppresses P2R. Increasing the peak Ito promotes spiral wave breakup, but increasing the late Ito prevents spiral wave breakup by flattening the AP duration (APD) restitution and preventing focal excitations. For ICa,L, a sufficiently large peak conductance is required for P2R, but above a critical conductance, further increases in ICa,L suppress P2R. Moreover, increasing the window and late ICa,L promotes P2R by countering the P2R-suppressing effect of the late Ito. For INa, blocking either the peak or the late component promotes P2R, with the late INa blockade exhibiting the larger effect. Increasing other K+ currents, such as IKs, IKr or IK-ATP, can promote P2R, with IK-ATP exhibiting the largest effect. Men are more susceptible to P2R, mainly because men have a larger Ito and a smaller ICa,L than women. For the same reason, P2R is more likely to occur at nighttime than daytime. The implications for arrhythmogenesis and therapies of BrS are discussed.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No institutional review board approval was necessary since only simulations were performed.

1D cable and 2D tissue model.

We carried out single cell, 1D cable, and 2D tissue simulations. For the 1D cable model, the governing equation for voltage (V) is:

| (1) |

where Cm is the capacitance and Iion is the total ionic current density described by the 1994 Luo and Rudy model 13. Isti is the stimulus current density of a 0.5 ms pulse with a −80 μA/cm2. Dx is the diffusion constant representing the gap junction coupling strength.

The governing equation for voltage in the 2D tissue model is:

| (2) |

We also performed 1D cable and 2D tissue simulations using the 2004 ten Tusscher et al human ventricular AP model 14 and the results are shown in Figs.V–X and Movies II–IV in Data Supplement. The parameter settings for heterogeneities, calculation of pseudo-ECG, and the numerical methods are also presented as supplemental methods in Data Supplement. Unless stated specifically, the parameters were the same as in the original cell models.

Ito model.

For either the 1994 Luo and Rudy model or the 2004 ten Tusscher et al model, we used (or substituted the Ito in the ten Tusscher et al model with) the Ito formulation by Dumaine et al 15:

| (3) |

where Gto is the maximum conductance, z is the activation gating variable, and y is the inactivation gating variable. To vary the late component of Ito, we altered the steady-state inactivation as

| (4) |

where γ controls the strength of the late Ito and increasing γ increases the late component.

Results

Late Ito coverts type 1 ECG to type 2 ECG and prevents P2R

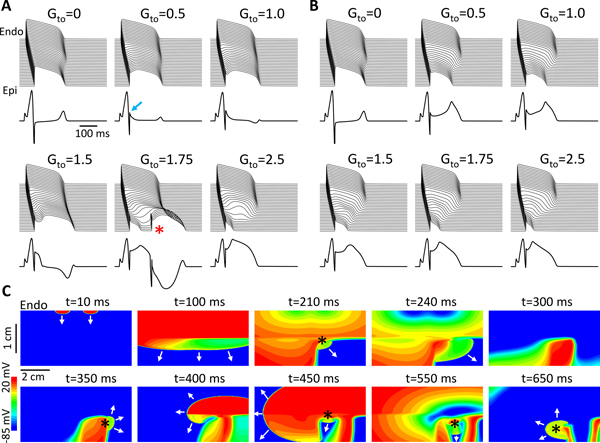

We first carried out 2D tissue simulations to demonstrate the effects of late Ito on ECG morphology and the occurrence of P2R. We altered the late Ito in the model by changing γ as described in Eq.4. Fig.1A shows the time-space plots of voltage and the corresponding pseudo-ECGs for different maximum Ito conductance (Gto) for γ = 0. When Gto=0, the T-wave was upright since the APD was shorter in the epicardium. As Gto was increased, the J-point and the ST-segment became elevated, and the T-wave amplitude became smaller and then negative. When Gto was large still, the ST-segment then became coved (type 1) and spontaneous PVCs began to occur. As Gto was increased even further, the APD shortened on the epicardial side and the ST-segment became highly elevated, but spontaneous PVCs disappeared. The coved ECGs were also promoted by blocking INa or ICa,L when Gto was large enough (see Fig.II in Data Supplement). For γ = 0.1 (Fig.1B), both the J-point and ST-segment become elevated with a saddleback ST-segment (type 2) as Gto was increased, but no PVCs occurred for any Gto values.

Figure 1. Effects of late Ito on ST-segment properties and P2R.

Simulations were carried out in a 2D tissue model with an endocardial-to-epicardial Ito gradient. A. Time-space plots of V and ECGs for different levels of Gto (in unit mS/cm2) when γ = 0. The arrow in the 2nd panel points to the elevated J-point. The asterisk in the 5th panel indicates the P2R/PVC. B. Same as A but when γ = 0.1. C. Wave dynamics in the same 2D tissue as for A but with an Ito heterogeneity in the longitudinal direction. Shown are voltage snapshots at different time points. Arrows indicate propagating wavefronts. A wave elicited from two stimulus sites (t=10 ms) propagated from the endocardium to epicardium (t=100 ms). Due to the early repolarization in the lower-right quadrant, a P2R occurred (t=210 ms, marked by *), propagated toward the tissue boundary (t=240 ms) and disappeared. The repolarization pattern remained heterogeneous (t=300 ms) and a new P2R occurred (t=350 ms) that propagated as a spiral wave reentry (t=400 ms) before wandering off the tissue boundary (t=450 ms). New P2Rs (*) also occurred in snapshots at t=450, 550, and 650 ms. Due to the tissue size, the last P2R shown in t=650 ms was not able to survive, and the tissue became quiescent before the next pacing beat. See Movie I in Data Supplement for the detailed wave dynamics. Tissue size was 7.68 cm × 1.92 cm.

In simulated 2D tissue with an endo-epi gradient in Ito density, PVCs occurred, but reentry was never observed. However, when a longitudinal gradient in Ito density was also introduced, spontaneous PVCs began to initiate reentry. Fig.1C shows voltage snapshots at different time points illustrating the spontaneous formation of reentry in the 2D tissue model with both transmural and longitudinal heterogeneities (see Movie I in Data Supplement for the entire episode). Note that after the first episode of P2R, repolarization heterogeneities became very dynamic, resulting in additional P2R episodes at different locations in the tissue. Depending on the tissue size and degree of heterogeneity, P2R could manifest as a single PVC or induce non-sustained and sustained arrhythmias.

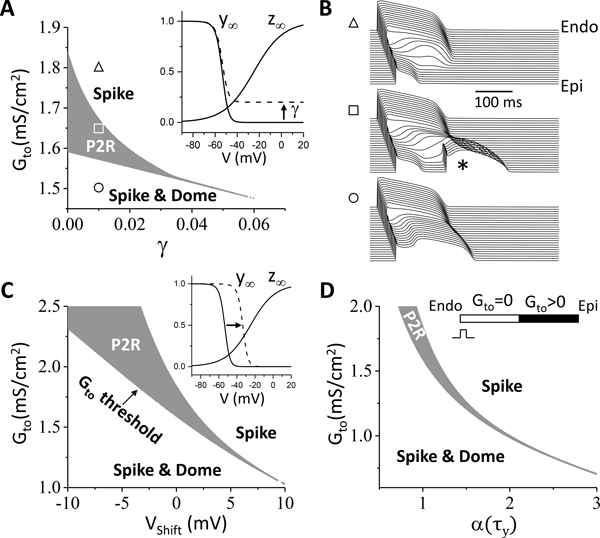

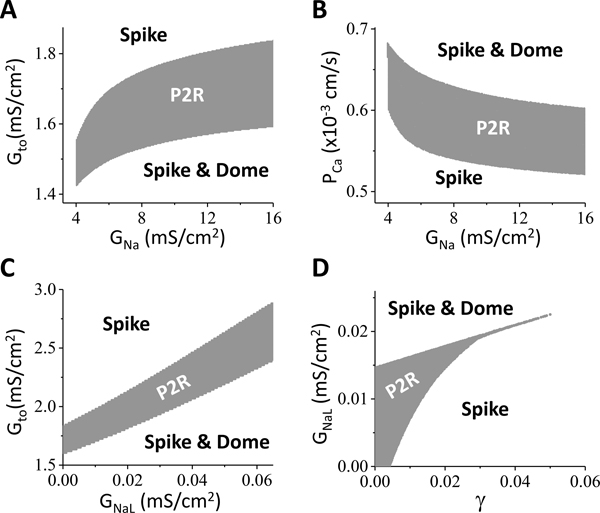

To provide a systematic analysis of the effects Ito on P2R, we carried out simulations in a 1D cable in which all other ionic currents were uniform except Ito. Gto in one half (the “endocardial” side) of the cable was zero and the other half (the “epicardial” side) was non-zero, as illustrated in the inset of Fig.2D. The cable was paced from the “endocardial” side. In the 1D cable, only PVCs were observed, which, for simplicity, we also call P2Rs. Fig.2A shows the P2R region versus Gto and γ from the 1D cable simulations obtained by scanning Gto and γ with small increments. At γ = 0, P2R occurred for Gto between 1.59 and 1.85 mS/cm2 (see the middle panel in Fig.2B for an example of time-space plot of voltage for P2R). When Gto was smaller than 1.59 mS/cm2, the spike-and-dome AP morphology occurred in the epicardial side of the cable (see the lower panel in Fig.2B) with a later repolarization. When Gto was larger than 1.85 mS/cm2, the AP became a spike on the epicardial side with very early repolarization (see the upper panel in Fig.2B). In this case, the tissue was very heterogeneous. Although the Gto threshold for P2R (the boundary between “Spike & Dome” and “P2R”) decreased as γ increased, the P2R region shrank quickly, and no P2R occurred when γ > 0.06. This agrees with the observation in Fig.1 that increasing the late Ito converts type 1 ECG to type 2 ECG and suppresses P2R.

Figure 2. Effects of Ito properties on P2R.

1D cable simulations with a single pacing beat from the endocardium. The cable is uniform except that Ito is heterogeneous as indicated in the inset of panel D. The gray region is the P2R region. The region marked by “Spike & Dome” is the region where the AP is normal or exhibits a spike-and-dome morphology in the endocardial side (see the lower panel in B). The region marked by “Spike” is the region where the AP in the epicardial side becomes a spike with a very abbreviated APD (see the upper panel in B). The boundary between the “Spike & Dome” region to the “P2R” region is the threshold for P2R as indicated in C. A. P2R region versus Gto and γ. γ (Eq.4) controls the level of incomplete inactivation of the steady state as indicated in the inset. B. Space and time plots of V from the parameter locations marked in A. Asterisk indicates the PVC. C. P2R region versus Gto and the voltage shift (Vshift) of the steady-state inactivation curve (y∞) as indicated in the inset. Vshift>0 means a right shift and vice versa. D. P2R region versus Gto and the inactivation time constant τy. α (τy) is the fold change of τy.

We also investigated the effects of window Ito and inactivation time constant on P2R. Fig.2C shows the P2R region versus Gto and the voltage shift (Vshift) of the steady-state inactivation curve (y∞). Increasing the window Ito (shifting the curve rightward, Vshift>0) shrank the Gto range for P2R. However, this also caused P2R to occur at a lower Gto. Slowing inactivation suppressed the Gto range for P2R but also lowered the Gto threshold. Note that increasing the window Ito or slowing Ito inactivation exhibited a much larger effect on lowering the Gto threshold for P2R than increasing γ. This is because shifting y∞ or slowing inactivation increased the late component of Ito, which tended to suppress P2R, but also increased the amplitude of Ito, which lowered the Gto threshold for P2R. Therefore, it is unclear if a strategy of altering window Ito or its inactivation time constant would promote or suppress P2R.

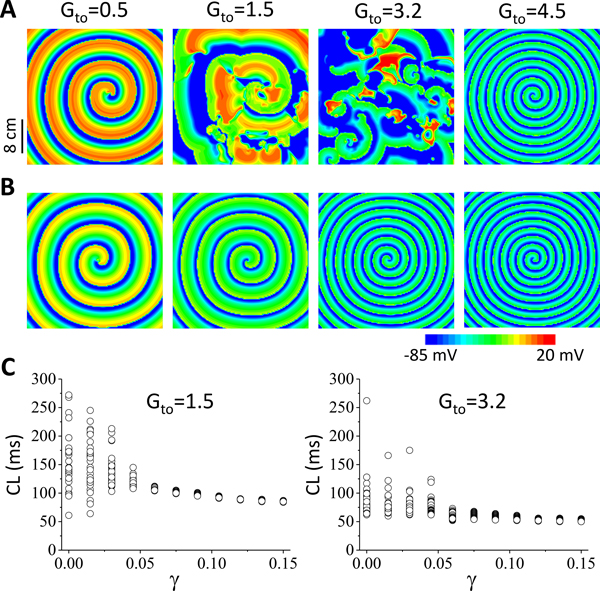

In Fig.2, the simulations were performed for a fixed initial condition with a single pacing beat. To investigate how continuous pacing and late Ito affect P2R, we paced the cable with two other pacing protocols: periodic pacing and random pacing (Fig.3). Fig.3A shows the P2R region and percent of the beats exhibiting PVCs versus Gto and pacing cycle length (PCL) for γ = 0, γ = 0.02, and γ = 0.05. The P2R region (Gto range) decreased as PCL was increased or as γ was increased. Moreover, the percentage of the beats exhibiting PVCs increased with PCL but decreased sharply with γ. Note that although the cable was paced periodically, not all beats exhibited PVCs due to the complex dynamics (see a time-space plot of voltage for an example in Fig.III in Data Supplement). In the simulations in Fig.3A, we only paced 200 beats for each combination of Gto and PCL. To obtain more accurate statistics on PVC rates, we paced 2000 beats for a fixed PCL (1500 ms) and different Gto for the three γ values. We calculated the percentage of the beats exhibiting a PVC and plotted it against Gto in Fig.3B for the three γ values. For γ = 0, the highest PVC rate was 60%. When γ = 0.02, the highest PVC rate was less than 10% and decreased to less than 1% for γ = 0.05. We did not observe any PVCs for γ > 0.07 for the 2000 pacing beats. We also used a random pacing protocol in which we randomly picked the PCLs in the interval from 500 ms to 1500 ms, and paced for 2000 beats for each chosen Gto. Fig.3C shows the percentage of the beats exhibiting PVCs against Gto for the three γ values. The PVC rates became lower but the Gto ranges were wider than for the periodic pacing. We did not observe any PVCs when used γ=0.05 or larger.

Figure 3. Dependence of P2R on heart rate and late Ito.

1D cable simulations with periodic or random pacing from the endocardium. A. Percentage of beats exhibiting PVCs versus Gto and PCL under periodic pacing for γ = 0, γ = 0.02, and γ = 0.05. 200 pacing beats were applied for each combination of Gto and PCL. Color scale indicates the percentage of PVC beats. B. Histograms showing percentage of PVC beats versus Gto for γ = 0, γ = 0.02, and γ = 0.05 under periodic pacing with PCL=1500 ms. 2000 pacing beats were applied for each Gto. C. Same as B but for the random pacing protocol with random PCLs uniformly drawn from the interval between 500 ms and 1500 ms.

Note that although P2R occurred over a wider Gto range for the periodic and random pacing protocols (Fig.3) than those for the single-beat pacing (Fig.2A), the likelihood of P2R occurrence decreased sharply with γ in all three pacing protocols, and the threshold γ values for complete suppression of P2R were similar.

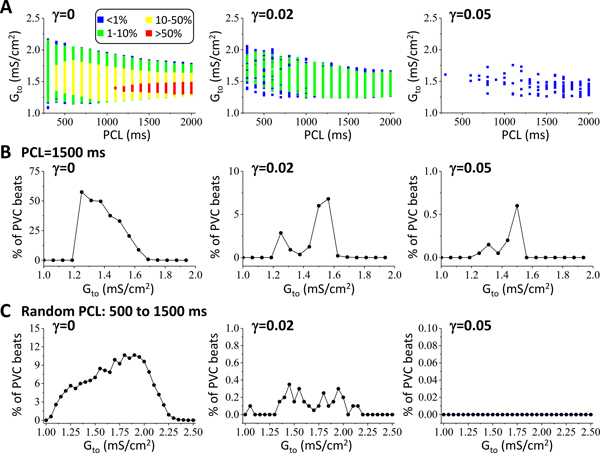

Late Ito stabilizes spiral wave reentry

In a previous study 16, we showed that Ito could destabilize spiral wave reentry, causing spiral wave breakup. Here we show that the late Ito stabilizes reentry and can prevent the spiral wave breakup caused by the peak Ito. Fig.4A shows voltage snapshots for four Gto values with γ = 0. When Gto was small, the spiral wave was stable. When Gto was in the intermediate range, spiral wave breakup occurred. When Gto was large, the spiral wave became stable again. The mechanisms that Ito promotes spiral wave instabilities have been investigated in our previous study 16. Fig.4B shows voltage snapshots for the same Gto values with γ = 0.2, and the spiral waves were all stable. In Fig.4C, we show the spiral wave cycle length (CL) versus γ for the two Gto values (1.5 and 3.2 mS/cm2) that gave rise to spiral wave breakup in Fig.4A, showing that increasing γ stabilized the spiral wave reentry, i.e., the CL became less variable and finally constant as γ was large enough.

Figure 4. Effects of late Ito on reentry stability in 2D homogeneous tissue.

A. Voltage snapshots for different Gto (in unit mS/cm2) for γ = 0. B. Same as A but for γ = 0.15. C. Cycle length (CL) of reentry versus γ for Gto=1.5 mS/cm2 and 3.2 mS/cm2. Since the tissue is homogeneous, reentry cannot occur spontaneous, and thus it was induced using the traditional cross-field protocol.

Mechanistic insights from cellular dynamics caused by late Ito

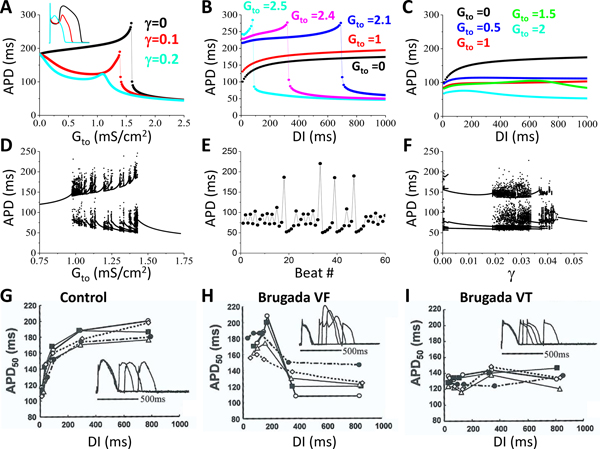

To better understand the effects of late Ito on the ECG morphology, P2R generation, and reentry stability, we carried out single-cell simulations to investigate the effects of the late Ito on APD, APD restitution, and APD dynamics. Fig.5A shows APD versus Gto for three γ values. For γ = 0, as Gto was increased from zero, APD increased slowly at first and then rapidly to a maximum before a sudden and discontinuous shortening (an all-or-none response). As γ was increased, the spike-and-dome morphology was attenuated, the APD lengthening was less prominent, and the sudden shortening was attenuated. When γ was large enough, the APD exhibited a continuous and graded response to Gto. Figs.5 B and C show APD restitution curves for different Gto for γ = 0 and γ = 0.2, respectively. For γ = 0 (Fig.5B), if Gto was small, we observed a regular monotonic APD restitution curve. For larger Gto, APD first increased with DI but then shortened suddenly and discontinuously at a certain DI, resulting in non-monotonic restitution curves. For γ = 0.2 (Fig.5C), APD increased with DI, similar to the regular monotonic APD restitution curve but became less steep with larger Gto. To show how Gto and γ affect the cellular APD dynamics, we paced the cell periodically. Fig.5D is a bifurcation diagram showing APD versus Gto for γ = 0. APD was regular for either small Gto or large Gto, but for the intermediate Gto, complex APD dynamics, such as alternans, high periodic and non-periodic behaviors occurred (see the example shown in Fig.5E). Increasing γ stabilized the APD dynamics (Fig.5F). Ito-promoted complex APD dynamics have been demonstrated previously in experiments and simulations 17–21.

Figure 5. Effects of late Ito on cellular properties.

A. APD versus Gto for three different γ values as marked. Inset shows the APs from the peaks of the three curves. B. S1S2 APD restitution for γ = 0 and different Gto as marked. C. S1S2 APD restitution for γ = 0.2 and different Gto as marked. D. APD versus Gto for γ = 0 under periodic pacing with PCL=500 ms. 200 consecutive APDs are plotted for each Gto. E. APD versus beat # for Gto=1.425 mS/cm2 from a simulation in D. F. APD versus γ for Gto=1.25 mS/cm2 under periodic pacing with PCL=500 ms. G-I. S1S2 APD restitution curves measured in experiments by Aiba et al 22 for control (G), the ones exhibiting VF (H), and the ones exhibiting VT (I). Panels G-I were modified from Aiba et al with permission.

The single-cell simulation results shown in Figs.5A–F provided the following mechanistic insights:

When the late Ito was small (e.g., the γ = 0 case in Fig.5A), APD increased with Gto but then suddenly shortened due to the sudden loss of the dome. Lengthening APD in the epicardial side resulted in a later repolarization, causing the positive T-wave to become negative and thus giving rise to the coved ST-segment. The sudden shortening of APD resulted in a large repolarization gradient, which together with a prominent spike-and-dome morphology resulted in P2R (see Fig.1A or Fig.2B). When the late Ito was large (e.g., the γ = 0.2 case in Fig.5A), APD decreased as Gto was increased, and APD remained shorter on the epicardial side than the endocardial side, which elevated both the ST-segment and the T-wave, resulting in the saddleback ST-segment.

In an experimental study, Aiba et al 22 showed different APD restitution properties under control conditions (Fig.5G), BrS with VF (Fig.5H), and BrS with VT (Fig.5I). The APD restitution curve under control conditions was a regular monotonic curve, which corresponded to the curves in the model for small Gto (Figs.5 B and C). For the BrS VF case, the APD restitution became a non-monotonic curve, in which APD first increased to a maximum and then decreased quickly as DI was increased. A similar restitution behavior was also observed experimentally in canine ventricular epicardial myocytes 17. This property agrees well with the APD restitution property in the model for small γ and large Gto (see Fig.5B). As shown in our simulations (Fig.4), spiral wave breakup occurred for small γ and large Gto. This agrees with the experimental observation that the non-monotonic APD restitution is associated with VF. For the BrS VT case, the APD restitution curve was flattened, which agrees with the APD restitution curves of the model when γ was large (Fig.5C). As shown in our simulations (Fig.4), increasing γ stabilized spiral waves. This agrees with the experimental observation that flatted APD restitution is associated with VT rather than VF. Therefore, our simulations agree with the experimental observations, providing mechanistic links between the late Ito, APD restitution, and VT and VF in BrS.

Effects of ICa,L and INa on P2R

As shown above, the peak and late Ito exhibited opposite effects on the genesis of P2R and reentry stability. Since ICa,L and INa also play important roles in arrhythmogenesis in BrS (by adjusting the background conditions upon which Ito operates), we investigated whether the different components of these two currents exhibit different effects on the genesis of P2R.

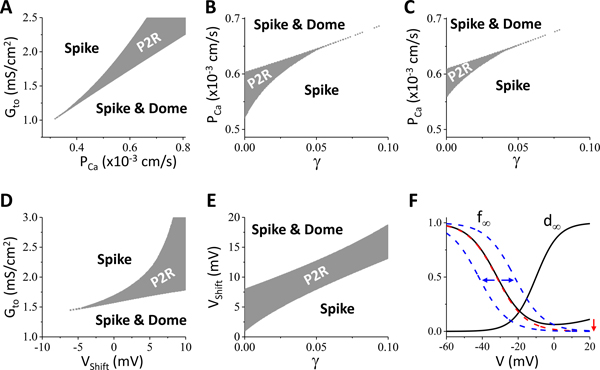

Fig.6 shows the effects of the different ICa,L components on the genesis of P2R. Fig.6A plots the P2R region versus PCa and Gto. PCa is the parameter describing the maximum conductance of ICa,L. For P2R to occur, a minimum PCa was needed. As PCa was increased, the Gto range for P2R increased, but at the same time, the Gto threshold for P2R became higher. Therefore, under the right conditions in which PCa was high, P2R could be promoted by reducing PCa. Fig.6B shows the P2R region versus γ and PCa, illustrating that although increasing γ lowered the PCa threshold (i.e., P2R occurs at a larger PCa), it quickly suppressed the PCa range for P2R. Removing the late component of ICa,L by removing the incomplete steady-state inactivation from the original formulation (see Fig.6F) resulted in a smaller PCa range of P2R (Fig.6C), indicating that P2R was potentiated by the late ICa,L. Increasing the window ICa,L (by shifting the steady-state inactivation curve rightward) raised the Gto threshold slowly but quickly increased the Gto range of P2R (Fig.6D). To show how the window ICa,L interacts with late Ito, we show in Fig.6E the P2R region versus γ and the voltage shift (Vshift) of the steady-state inactivation curve, showing that as γ was increased, the Vshift range for P2R remained roughly the same. This indicates that the effects of late Ito could be countered by the window ICa,L. The effects of late Ito could also be countered by the late ICa,L (see Fig.IV in Data Supplement). This is different from Fig.2A, Figs.6 B and C, in which the P2R regions shrank quickly with γ. The results in Fig.6 show that blocking the peak ICa,L may promote P2R by bringing the system closer to the threshold, but blocking the window and late ICa,L can effectively suppress P2R by reducing the size of the P2R region.

Figure 6. Effects of ICa,L on P2R.

Simulations were carried out in a 1D cable as for Fig.2. A. P2R versus PCa and Gto for γ = 0. PCa is a parameter proportional to the maximum conductance of ICa,L. B. P2R region versus γ and PCa for Gto=1.75 mS/cm2. C. Same as B but after removing the late component of ICa,L. This was done by removing the elevated part of the original f∞ in the high voltage range as indicated in panel F. D. Effects of window ICa,L on P2R, simulated by shifting f∞ as indicated in panel F. Shown is the P2R region versus Vshift and Gto. E. P2R region versus γ and Vshift. Gto=1.75 mS/cm2. F. Alterations of f∞. Solid black curve is the original f∞. Dashed red curve is the one after the late component removed, corresponding the change from panel B to panel C. Dashed blue curves indicate the right or left shift from the dashed red curve used in D and E. Vshift>0 for the right shift and Vshift<0 for the left shift.

Fig.7 illustrates the effects of the peak and late INa on the genesis of P2R. We added the formulation of late INa from Hund Rudy23 into the model. Fig.7A is a plot of the P2R region versus GNa and Gto, showing that changing GNa had a small effect on both the Gto threshold and the Gto range for P2R. For certain Gto values (e.g., Gto=1.5 mS/cm2), reducing GNa could promote P2R, indicating that blocking INa potentiates P2R. Fig.7B is a plot of the P2R region versus GNa and PCa, showing that reducing GNa slightly elevated the PCa threshold but had little effect on the PCa range for P2R. Fig.7C plots the P2R region versus the maximum conductance of late INa (GNaL) and Gto, showing that increasing GNaL had a small effect on the Gto range for P2R but raised the Gto threshold for P2R. Fig.7D plots the P2R region versus γ and GNaL, showing that increasing γ raised the GNaL threshold for P2R slightly, but the GNaL range for P2R shrank quickly. Thus, unlike the window ICa,L, the effects of the late INa are not countered by the effects of the late Ito component but rather by the effects of the peak Ito (Fig.7C).

Figure 7. Effects of INa on P2R.

Simulations were carried out in a 1D cable as for Fig.2. A. P2R region versus GNa and Gto. B. P2R region versus GNa and PCa. Gto=1.75 mS/cm2. C. P2R region versus GNaL and Gto. D. P2R region versus γ and GNaL. In A and B, GNaL=0.

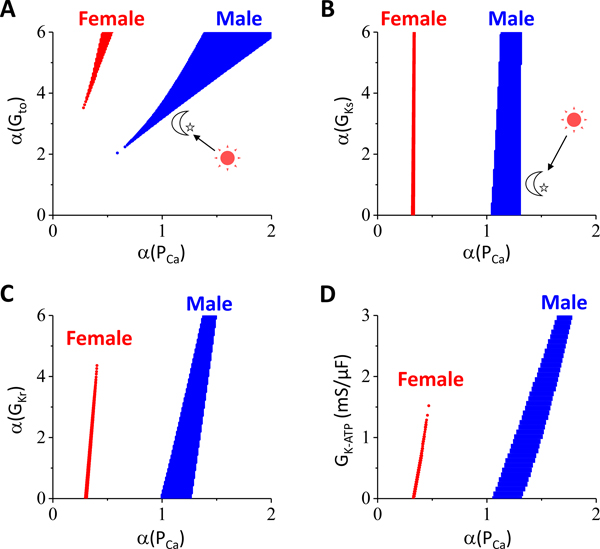

Effects of sex difference and circadian rhythm on P2R

The vast majority of BrS patients are male (91.3%) 24 with arrhythmia risk being higher after midnight 25–28, possibly because current densities differ in male and female hearts and exhibit different responses to sex hormones 29–34 and circadian rhythm 35–37. To investigate the effects on P2R, we carried out additional 1D cable simulations. We set the female-to-male ratios of the maximum conductance of the ionic currents (See Table I in Data Supplement) based on previous studies30, 33. The K+ currents are smaller and ICa,L is larger in female than in male. Fig.8A shows the P2R regions versus fold change of the maximum conductance of ICa,L and Ito for male (blue) and female (red). The P2R region was much smaller for female than for male, and started at a lower fold change of ICa,L and a higher fold change of Ito. Therefore, a much larger increase in Ito and/or a much larger reduction in ICa,L is required to produce P2R in females, agreeing with the clinical profile of BrS occurring predominantly in men. Fig.8B plots the P2R regions for male and female versus the fold changes of ICa,L and IKs, showing that increasing GKs exhibited a very small effect on promoting P2R. It has been shown that ICa,L is reduced during nighttime 35, 36 while Ito is increased during nighttime 37 (as indicated by the arrow from sun to moon in Fig.8A). In addition, β-adrenergic activity, which elevates both ICa,L and IKs, is higher during daytime than nighttime and thus both ICa,L and IKs are smaller during nighttime than daytime (as indicated by the arrow from sun to moon in Fig.8B). Therefore, our simulations indicate that P2R is more likely to occur during nighttime than daytime, agreeing with the clinical observation. Figs.8 C and D show two sets of additional simulations for the effects of IKr and IK-ATP on P2R. The mathematical model of IK-ATP was taken from Shaw and Rudy 38. Increasing GKr or GK-ATP caused P2R to occur at a larger PCa, indicating that increasing IKr or IK-ATP promotes P2R. Note that for the three K+ currents (Figs.8 B–D), IK-ATP exhibits the largest effect on promoting P2R and IKs the smallest effect, which is more prominent in the ten Tusscher et al human model (see Fig.X in Data Supplement).

Figure 8. Effects of sex difference and circadian rhythm on P2R.

Simulations were done in the 1D cable as for Fig.2 except that the maximum conductances of ionic currents were different for female and male. The control parameters for male were the same as for Fig.2. The female-to-male ratios of the maximum conductance were shown in Table I in Data Supplement. α is the fold change of the maximum conductance from the control values. For example, α(PCa) implies the PCa value is α-fold of the control PCa for either female or male. Similar to Fig.6A, the “Spike & Dome” region is in the right and the “Spike” region is in left of the P2R region for all the panels in this figure. A. P2R regions for male and female versus α(PCa) and α(Gto). B. P2R regions for male and female versus α(PCa) and α(GKs). C. P2R regions for male and female versus α(PCa) and α(GKr). D. P2R regions for male and female versus α(PCa) and GK-ATP. Since there was no IK-ATP in control, GK-ATP instead of α(GK-ATP) was used in this panel. α(Gto)=4 was used for B-D. Note that the P2R region in D is more tilted to the right than those in B and C, indicating that IK-ATP exhibits a larger effect in changing the ICa,L threshold for P2R and thus a larger effect on promoting P2R. In the ten Tusscher human model, we observed an even more tilted P2R region which also expanded as GK-ATP increased (see Fig.XD in Data Supplement).

Discussion

Three types of characteristic ECGs are associated with BrS, but only type 1 is diagnostic. In this study, we carried out computer simulations to investigate the effects of different components of Ito, ICa,L, and INa, as well as other K+ currents, on the genesis of P2R and the stability of reentry in BrS. Our major findings are that the late Ito component suppresses the spike-and-dome morphology and shortens APD, converting type 1 ECG to type 2 ECG and preventing P2R. The peak Ito promotes spiral wave breakup, promoting VF, but the late Ito stabilizes reentry, converting VF to VT. Blocking the peak ICa,L potentiates P2R but blocking the window or the late ICa,L suppresses P2R. Bocking the peak or the late INa promotes P2R with the late INa exhibiting a larger effect. Increasing other K+ currents, such as IKs, IKr or IK-ATP, can promote P2R, with IK-ATP exhibiting the largest effect. Men is more susceptible to P2R, mainly due to that men have a larger Ito and a smaller ICa,L than women. For the same reason, P2R is more likely to occur at nighttime than daytime. We performed the same simulations using the ten Tusscher et al human ventricular AP model 14 and obtained almost the same results (see Figs.V–X in Data Supplement), indicating that the findings are not likely model dependent. The mechanistic insights from our computer simulation results and the implications for arrhythmogenesis and potential therapies for BrS are discussed below.

Ionic mechanisms of ECG morphology and links to P2R

The AP configurations giving rise to coved and saddleback ECG were first proposed by Antzelevitch 9, and our simulations agree with their interpretation. An additional insight from our simulations is the contribution of the late Ito component to the ECG characteristics. Combined with the insight from our simulations into the role of late Ito in the genesis of P2R, we link the ECG characteristics with the genesis of P2R. More specifically, when Ito is large with a small late component, the spike-and-dome AP morphology is prominent and a coved ST-segment (type 1) occurs (e.g., the case with Gto=1.5 in Fig.1A). When Ito and its late component are both small, a type 3 ECG occurs (e.g., the cases with Gto=0.5 and 1 in Fig.1A). When the late component is large, the AP dome is attenuated and a saddleback ST-segment (type 2) occurs (e.g., the cases with Gto=0.5 and 1 in Fig.1B). Since a large Ito is needed for P2R, the Ito giving rise to type 3 ECG is still far away from the threshold for P2R. For the Ito giving rise to type 2 ECG, its late component maybe too strong to allow P2R to occur. Note that when the overall Ito is very large with or without the late component, APD becomes very short in the epicardium (the “Spike” regions in Figs. 2, 6, and 7), resulting in a highly elevated ST-segment (e.g., the large Gto cases in Figs. 1 A and B). The effects of the late Ito can be countered by the window or the late ICa,L.

Roles of late Ito on P2R formation and stability

Unlike the traditional mechanisms of reentry formation in which a PVC and a vulnerable heterogeneous tissue substrate may arise from independent processes 39, the PVC and heterogeneous tissue substrate in P2R arise from the same dynamical process. Mechanisms of P2R have been investigated in computer simulation studies 40, 41. In a recent study 42, we analyzed the dynamical mechanisms of P2R genesis and showed that the occurrence of P2R is determined by two factors: 1) the transition from the spike-and-dome AP morphology to the spike AP morphology in the single cell; and 2) the spatial instability caused by the repolarization heterogeneity in tissue. The former determines the parameter threshold and the later determines the size (or the parameter range) of the P2R region. For example, for γ = 0, the spike-and-dome to spike transition in the single cell occurs at Gto=1.59 mS/cm2 (Fig.5A) while the Gto threshold for P2R in the cable is also 1.59 mS/cm2 (Fig.2A). Increasing γ reduces the Gto for the spike-and-dome to spike transition (Fig.5A), agreeing with increasing γ decreasing the threshold for P2R (Fig.2A). Even for γ = 0, P2R occurs in a range of Gto above the threshold, and when Ito is too strong, P2R is suppressed due to suppression of the spatial instability 42. As shown in Fig.2A, the late Ito exhibits a strong effect on suppressing the spatial instability, i.e., the P2R region is reduced quickly as γ increases. In the diagrams shown in Figs.2, 6, and 7, the parameter threshold is the boundary between the “Spike & Dome” and “P2R” and the gray region is the parameter range for P2R. As shown in these figures, different ionic currents or their different components exhibit different effects on the threshold for P2R and the size of the P2R region.

Besides suppressing the genesis of P2R, late Ito can also prevent spiral wave breakup. We showed in a previous study 16 that Ito could promote spiral wave breakup by steepening the APD restitution curves. Besides the steep APD restitution-induced breakup, we also observed P2Rs resulting from the complex wave dynamics, giving rise to a mixture of spontaneous firings (P2Rs) and spiral wave reentry (see Fig.VII and Movies III and IV in Data Supplement). Since late Ito flattens APD restitution and suppresses P2R, it stabilizes spiral wave reentry, preventing the occurrence of VF. This provides an ionic mechanism for the association of VT and VF to the different APD restitution properties observed in the experiments by Aiba et al 22.

The late component of Ito can be caused by incomplete inactivation or slow inactivation. As shown in Fig.2D, speeding up inactivation enlarges the region but elevates the Gto threshold for P2R. Therefore, whether a drug that speeds up inactivation is anti- or pro-arrhythmic depends on the relative effects on the peak and the late components. For example, experimental studies showed that acacetin caused a faster inactivation and greatly reduced the amplitude of Ito 43, which effectively prevented P2R 44. On the other hand, the ability of ajmaline and flecainide to promote type 1 ECG and P2R has been attributed to their effects on blocking INa. However, it is also shown that they may reduce Ito by speeding up inactivation 45–47. Reducing peak Ito might oppose their effect on suppressing P2R, but reducing the late component due to fast inactivation might promote type 1 ECG and P2R. Therefore, whether a drug speeding up Ito inactivation promotes or suppresses P2R may depend on its differential effects on reducing the peak and the late components of Ito.

Implications to arrhythmogenesis and therapies for BrS

As discussed above, the occurrence of P2R is determined by the parameter threshold and the parameter range, and different ionic currents and their different components affect these properties differently. So far 23 BrS mutations have been identified 48 causing either a loss of function of INa or ICa,L, or a gain of function of Ito or IK-ATP. Our simulation results show that P2R is promoted by reduction of INa (Fig.7) or ICa,L (Fig.6), or increase of Ito (Fig.2) or IK-ATP (Fig.8), agreeing in general with the clinical consequences of the BrS mutations. In addition, our simulations offer the following insights into the genesis and prevention of arrhythmias for BrS:

Ito amplitude needs to be large enough but not too large for P2R to occur, i.e., there is a range of optimal Ito strength for P2R (Fig.2). The P2R region becomes smaller as the late component increases and then completely disappears. Prior to the P2R region (i.e., in “Spike & Dome” region), the ST-segment is coved. Beyond the P2R region (i.e., in the “Spike” region), particularly for large late Ito, the ST-segment becomes saddleback. Therefore, to suppress P2R using Ito as a target, one can either block the Ito amplitude or enhance its late component. However, a drug preferentially blocking the late component may convert a type 2 ECG to a type 1 ECG and promote P2R.

As for ICa,L (Fig.6), when Ito is strong, reducing the maximum conductance of ICa,L promotes P2R, in agreement with the general knowledge of the effects of ICa,L on P2R and arrhythmogenesis in BrS. Interestingly, blocking the window or the late components of ICa,L does not promote P2R, but instead suppress P2R, providing a novel therapeutic target for BrS.

As for INa (Fig.7), blocking either the peak or the late component can promote P2R, with the late component being more sensitive. While increasing late INa can suppress P2R, however, it is well-known that increasing late INa can also promote long QT associated arrhythmias.

Note that in real hearts, Ito is not the only transient outward current. Other transient outward currents can exhibit similar effects as Ito to influence the genesis of P2R. For example, the Ca2+-activated small conductance K+ current is a transient outward current 49, 50 known to promote J-wave syndrome and P2R 51–53. The Ca2+-activated chloride current is also a spiky transient outward current 54, 55 that may potentiate P2R. On the other hand, the late components of these currents are likely to have the same effects as those of late Ito. These currents may contribute to the ECG morphologies and P2R genesis in the real heart.

Limitations

Several limitations should be mentioned. Pseudo-ECGs were calculated in 2D tissue and a whole-heart simulation may result in more realistic ECG morphologies 56. We mainly simulated the endo-epi heterogeneity in Ito conductance. P2R can occur due to the Ito heterogeneities in the epicardium, or due to transmural or base-to-apex heterogeneities of other ionic currents. It also hypothesized that regional slow conduction in the right ventricle due to fibrosis can also result in coved ECG morphology 57, and may provide an alternative or synergistic mechanism promoting reentrant arrhythmias in BrS (the so-called depolarization hypothesis 58), which is a subject for investigation in future simulation studies.

Conclusions

While the peak Ito promotes the type 1 ECG morphology and P2R in BrS, the late component can convert type 1 to type 2 ECG and suppress P2R. The late Ito can also stabilize spiral wave reentry, converting VF to VT. Therefore, blocking the peak Ito is antiarrhythmic but blocking the late component can be proarrhythmic in patients with BrS. Our simulations also show that blocking either the peak or the late INa can be proarrhythmic. Blocking the peak ICa,L is also proarrhythmic, whereas blocking the window or the late ICa,L components are antiarrhythmic. These observations may provide valuable insights for guiding the development of novel therapeutic targets for prevention of arrhythmias in BrS.

Supplementary Material

What is known?

Three types of characteristic ECGs are associated with Brugada syndrome, only type 1 (coved ST-segment) is diagnostic.

Phase 2 reentry induced by Ito is a candidate mechanism of arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome.

What the study adds?

Computer simulations provide mechanistic insights into why only type 1 is diagnostic, showing that the peak Ito promotes type 1 ECG and phase 2 reentry, but the late component of Ito converts coved ECG into saddleback (type 2) ECG and suppresses phase 2 reentry.

Besides the well-known fact that blocking an inward current or enhancing an outward current promotes phase 2 reentry, blocking the window and late calcium current suppresses phase 2 reentry.

Sources of funding:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL139829, R01 HL134709, and OT2OD028190. ZZ was also supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos.11605098 and 11975131; the Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo under Grant Nos. 2017A610142, 2019A610455 and 2019C50001; and K. C. Wong Magna Fund at Ningbo University.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 1D

1-dimensional

- 2D

2-dimensional

- AP

action potential

- APD

action potential duration

- BrS

Brugada syndrome

- CL

cycle length

- DI

diastolic interval

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- PVC

premature ventricular complex

- PCL

pacing cycle length

- P2R

phase 2 reentry

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

- VF

ventricular fibrillation

- Na+

sodium ion

- Ca2+

calcium ion

- K+

potassium ion

- Ito

transient outward potassium current

- ICa,L

L-type calcium current

- IKr

rapid component of the delayed rectifier potassium current

- IKs

slow component of the delayed rectifier potassium current

- INa

sodium current

- IK-ATP

ATP-sensitive potassium current

- INaL

late sodium current

- Gto

maximum conductance of Ito

- PCa

maximum conductance of ICa,L

- GNa

maximum conductance of INa

- GNaL

maximum conductance of INaL

- GKr

maximum conductance of IKr

- GKs

maximum conductance of IKs

- GK-ATP

maximum conductance of IK-ATP

- γ

parameter controlling strength of late Ito

Footnotes

Disclosure: None

Supplemental Materials

References

- 1.Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: A distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome: A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Right Bundle-Branch Block and ST-Segment Elevation in Leads V1 Through V3. Circulation. 1998;97:457–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Brugada J, Brugada R, Shimizu W, Gussak I, Riera ARP. Brugada Syndrome. Circ Res. 2002;91:1114–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antzelevitch C, Yan G-X. J-wave syndromes: Brugada and early repolarization syndromes. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1852–1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, Elliott PM, Fitzsimons D, Hatala R, Hindricks G, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2793–2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilde AAM, Antzelevitch C, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P, Corrado D, Hauer RNW, Kass RS, Nademanee K, et al. Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for the Brugada Syndrome. Circulation. 2002;106:2514–2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antzelevitch C, Yan G-X, Ackerman MJ, Borggrefe M, Corrado D, Guo J, Gussak I, Hasdemir C, Horie M, Huikuri H, et al. J-Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report: Emerging concepts and gaps in knowledge. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:e295–e324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Priori SG, Gasparini M, Napolitano C, Bella PD, Ottonelli AG, Sassone B, Giordano U, Pappone C, Mascioli G, Rossetti G, et al. Risk Stratification in Brugada Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antzelevitch C The Brugada syndrome: ionic basis and arrhythmia mechanisms. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Diego JM, Antzelevitch C. Pinacidil-induced electrical heterogeneity and extrasystolic activity in canine ventricular tissues. Does activation of ATP-regulated potassium current promote phase 2 reentry? Circulation. 1993;88:1177–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lukas A, Antzelevitch C. Phase 2 reentry as a mechanism of initiation of circus movement reentry in canine epicardium exposed to simulated ischemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:593–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan GX, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the Brugada syndrome and other mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis associated with ST-segment elevation. Circulation. 1999;100:1660–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo CH, Rudy Y. A dynamical model of the cardiac ventricular action potential: I. simulations of ionic currents and concentration changes. Circ. Res. 1994;74:1071–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ten Tusscher KH, Noble D, Noble PJ, Panfilov AV. A model for human ventricular tissue. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1573–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumaine R, Towbin JA, Brugada P, Vatta M, Nesterenko DV, Nesterenko VV, Brugada J, Brugada R, Antzelevitch C. Ionic Mechanisms Responsible for the Electrocardiographic Phenotype of the Brugada Syndrome Are Temperature Dependent. Circ Res. 1999;85:803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landaw J, Yuan X, Chen P- S, Qu Z. The transient outward potassium current plays a key role in spiral wave breakup in ventricular tissue. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;320:H826–H837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lukas A, Antzelevitch C. Differences in the electrophysiological response of canine ventricular epicardium and endocardium to ischemia. Role of the transient outward current. Circulation. 1993;88:2903–2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clancy CE, Rudy Y. Na(+) channel mutation that causes both Brugada and long-QT syndrome phenotypes: a simulation study of mechanism. Circulation. 2002;105:1208–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopenfeld B Mechanism for action potential alternans: the interplay between L-type calcium current and transient outward current. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landaw J, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN, Qu Z. Memory-Induced Chaos in Cardiac Excitation. Phys Rev Lett. 2017;118:138101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landaw J, Qu Z. Memory-induced nonlinear dynamics of excitation in cardiac diseases. Phys Rev E. 2018;97:042414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aiba T, Shimizu W, Hidaka I, Uemura K, Noda T, Zheng C, Kamiya A, Inagaki M, Sugimachi M, Sunagawa K. Cellular Basis for Trigger and Maintenance of Ventricular Fibrillation in the Brugada Syndrome Model: High-Resolution Optical Mapping Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2074–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hund TJ, Rudy Y. Rate dependence and regulation of action potential and calcium transient in a canine cardiac ventricular cell model. Circulation. 2004;110:3168–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milman A, Gourraud J-B, Andorin A, Postema PG, Sacher F, Mabo P, Conte G, Giustetto C, Sarquella-Brugada G, Hochstadt A, et al. Gender differences in patients with Brugada syndrome and arrhythmic events: Data from a survey on arrhythmic events in 678 patients. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:1457–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaki M, Sato N, Okada M, Fujita S, Go K, Sakamoto N, Tanabe Y, Takeuchi T, Kawamura Y, Hasebe N. A Case of Brugada Syndrome in Which Diurnal ECG Changes Were Associated With Circadian Rhythms of Sex Hormones. Int Heart J. 2009;50:669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S-H, Nam G-B, Baek S, OH Choi H, Hun KIm K, Choi K-J, Joung B, Pak H-N, Lee M-H, Soon Kim S, et al. Circadian and Seasonal Variations of Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias in Patients with Early Repolarization Syndrome and Brugada Syndrome: Analysis of Patients with Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:757–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takigawa M, Noda T, Shimizu W, Miyamoto K, Okamura H, Satomi K, Suyama K, Aihara N, Kamakura S, Kurita T. Seasonal and circadian distributions of ventricular fibrillation in patients with Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1523–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuo K, Kurita T, Inagaki M, Kakishita M, Aihara N, Shimizu W, Taguchi A, Suyama K, Kamakura S, Shimomura K. The circadian pattern of the development of ventricular fibrillation in patients with Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen M, Fei Y, Chen T-Z, Li Y-G, Chen P-S. The regulation of the small-conductance calcium-activated potassium current and the mechanisms of sex dimorphism in J wave syndrome. Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology. 2021;473:491–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang P-C, Perissinotti LL, López-Redondo F, Wang Y, DeMarco KR, Jeng M-T, Vorobyov I, Harvey RD, Kurokawa J, Noskov SY, et al. A multiscale computational modelling approach predicts mechanisms of female sex risk in the setting of arousal-induced arrhythmias. J Physiol. 2017;595:4695–4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurokawa J, Kodama M, Clancy CE, Furukawa T. Sex hormonal regulation of cardiac ion channels in drug-induced QT syndromes. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;168:23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odening KE, Koren G. How do sex hormones modify arrhythmogenesis in long QT syndrome? Sex hormone effects on arrhythmogenic substrate and triggered activity. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:2107–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaborit N, Varro A, Le Bouter S, Szuts V, Escande D, Nattel S, Demolombe S. Gender-related differences in ion-channel and transporter subunit expression in non-diseased human hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sims C, Reisenweber S, Viswanathan PC, Choi BR, Walker WH, Salama G. Sex, age, and regional differences in L-type calcium current are important determinants of arrhythmia phenotype in rabbit hearts with drug-induced long QT type 2. Circ Res. 2008;102:e86–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pennartz CMA, de Jeu MTG, Bos NPA, Schaap J, Geurtsen AMS. Diurnal modulation of pacemaker potentials and calcium current in the mammalian circadian clock. Nature. 2002;416:286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y, Zhu D, Yuan J, Han Z, Wang Y, Qian Z, Hou X, Wu T, Zou J. CLOCK-BMAL1 regulate the cardiac L-type calcium channel subunit CACNA1C through PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;94:1023–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeyaraj D, Haldar SM, Wan X, McCauley MD, Ripperger JA, Hu K, Lu Y, Eapen BL, Sharma N, Ficker E, et al. Circadian rhythms govern cardiac repolarization and arrhythmogenesis. Nature. 2012;483:96–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw RM, Rudy Y. Electrophysiologic effects of acute myocardial ischemia: a theoretical study of altered cell excitability and action potential duration. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:256–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qu Z, Weiss JN. Mechanisms of Ventricular Arrhythmias: From Molecular Fluctuations to Electrical Turbulence. Annu Rev Physiol. 2015;77:29–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maoz A, Krogh-Madsen T, Christini DJ. Instability in action potential morphology underlies phase 2 reentry: a mathematical modeling study. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:813–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyoshi S, Mitamura H, Fujikura K, Fukuda Y, Tanimoto K, Hagiwara Y, Ita M, Ogawa S. A mathematical model of phase 2 reentry: role of L-type Ca current. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1285–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Z, Qu Z. Life and death saddles in the heart. Phys Rev E. 2021;103:062406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li G-R, Wang H-B, Qin G-W, Jin M-W, Tang Q, Sun H-Y, Du X-L, Deng X-L, Zhang X-H, Chen J-B, et al. Acacetin, a Natural Flavone, Selectively Inhibits Human Atrial Repolarization Potassium Currents and Prevents Atrial Fibrillation in Dogs. Circulation. 2008;117:2449–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Diego JM, Patocskai B, Barajas-Martinez H, Borbáth V, Ackerman MJ, Burashnikov A, Clatot J, Li G-R, Robinson VM, Hu D, et al. Acacetin suppresses the electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestations of the J wave syndromes. PLOS ONE. 2020;15:e0242747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamashita T, Nakajima T, Hamada E, Hazama H, Omata M, Kurachi Y. Flecainide inhibits the transient outward current in atrial myocytes isolated from the rabbit heart. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1995;274:315–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Z, Fermini B, Nattel S. Effects of flecainide, quinidine, and 4-aminopyridine on transient outward and ultrarapid delayed rectifier currents in human atrial myocytes. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1995;272:184–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bébarová M, Matejovic P, Pásek M, Simurdová M, Simurda J. Effect of ajmaline on transient outward current in rat ventricular myocytes. General physiology and biophysics. 2005;24:27–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Antzelevitch C, Di Diego JM. J wave syndromes: What’s new? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2021;(in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamilton S, Polina I, Terentyeva R, Bronk P, Kim TY, Roder K, Clements RT, Koren G, Choi B-R, Terentyev D. PKA phosphorylation underlies functional recruitment of sarcolemmal SK2 channels in ventricular myocytes from hypertrophic hearts. J Physiol. 2020;598:2847–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terentyev D, Rochira JA, Terentyeva R, Roder K, Koren G, Li W. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release is both necessary and sufficient for SK channel activation in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306:H738–H746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen M, Xu D-Z, Wu AZ, Guo S, Wan J, Yin D, Lin S-F, Chen Z, Rubart-von der Lohe M, Everett THIV, et al. Concomitant SK current activation and sodium current inhibition cause J wave syndrome. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e122329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Landaw J, Zhang Z, Song Z, Liu MB, Olcese R, Chen P-S, Weiss JN, Qu Z. Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels promote J-wave syndrome and phase 2 reentry. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:1582–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fei Y-D, Chen M, Guo S, Ueoka A, Chen Z, Rubart-von der Lohe M, Everett TH, Qu Z, Weiss JN, Chen P-S. Simultaneous activation of the small conductance calcium-activated potassium current by acetylcholine and inhibition of sodium current by ajmaline cause J-wave syndrome in Langendorff-perfused rabbit ventricles. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18:98–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hegyi B, Bossuyt J, Griffiths LG, Shimkunas R, Coulibaly Z, Jian Z, Grimsrud KN, Sondergaard CS, Ginsburg KS, Chiamvimonvat N, et al. Complex electrophysiological remodeling in postinfarction ischemic heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E3036–E3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verkerk AO, Veldkamp MW, Baartscheer A, Schumacher CA, Klöpping C, Ginneken ACGv, Ravesloot JH. Ionic Mechanism of Delayed Afterdepolarizations in Ventricular Cells Isolated From Human End-Stage Failing Hearts. Circulation. 2001;104:2728–2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xia L, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Wei Q, Liu F, Crozier S. Simulation of Brugada syndrome using cellular and three-dimensional whole-heart modeling approaches. Physiol Meas. 2006;27:1125–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoogendijk MG, Opthof T, Postema PG, Wilde AAM, de Bakker JMT, Coronel R. The Brugada ECG Pattern. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weiss JN. Arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome: Defective depolarization, repolarization or both? JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021;7:271–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.