Abstract

The gram-negative bacterium Campylobacter jejuni has extensive reservoirs in livestock and the environment and is a frequent cause of gastroenteritis in humans. To date, the lack of (i) methods suitable for population genetic analysis and (ii) a universally accepted nomenclature has hindered studies of the epidemiology and population biology of this organism. Here, a multilocus sequence typing (MLST) system for this organism is described, which exploits the genetic variation present in seven housekeeping loci to determine the genetic relationships among isolates. The MLST system was established using 194 C. jejuni isolates of diverse origins, from humans, animals, and the environment. The allelic profiles, or sequence types (STs), of these isolates were deposited on the Internet (http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk), forming a virtual isolate collection which could be continually expanded. These data indicated that C. jejuni is genetically diverse, with a weakly clonal population structure, and that intra- and interspecies horizontal genetic exchange was common. Of the 155 STs observed, 51 (26% of the isolate collection) were unique, with the remainder of the collection being categorized into 11 lineages or clonal complexes of related STs with between 2 and 56 members. In some cases membership in a given lineage or ST correlated with the possession of a particular Penner HS serotype. Application of this approach to further isolate collections will enable an integrated global picture of C. jejuni epidemiology to be established and will permit more detailed studies of the population genetics of this organism.

Campylobacter jejuni is the most common causative agent of human enterocolitits in many industrialized countries, representing a substantial drain on public health resources. Typically, infection is associated with sudden onset of fever, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea containing blood and leukocytes (16, 30, 34). Sequelae occur occasionally, and links have been made between infection by particular C. jejuni serotypes and Guillain-Barré syndrome (24). The gram-negative bacterium is widespread in the environment (13), forming part of the natural intestinal flora of birds and mammals (17). The handling or consumption of raw or undercooked meat products, particularly chicken contaminated during slaughter, is often implicated in disease (3). However, the majority of C. jejuni infections are considered to be sporadic, with the source of infection remaining unidentified (2). Occasional larger-scale outbreaks of campylobacteriosis have been linked with consumption of contaminated water or raw milk (17, 27).

A plethora of methods have been developed to discriminate C. jejuni isolates for the investigation of epidemiology and infections. However, the lack of widely available reagents for methods such as serotyping has limited their general use. Genotyping methods have been developed (36), but the techniques and their interpretation have not been standardized or broadly accepted. This, coupled with the lack of a universal nomenclature system for isolate profiles, has prevented the development of an international campylobacter typing database.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (20) has been successful in the characterization of several other bacteria (1, 8, 20, 33). This technique employs the same philosophy as multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (29), in that neutral genetic variation from multiple chromosomal locations is indexed, but exploits nucleotide sequence determination to identify this variation. In MLST studies of other bacteria, stretches of nucleotide sequence of ∼500 bp from 7 loci provided discrimination approximately equivalent to that obtained with 15 to 20 loci in multilocus enzyme electrophoresis analyses (20). Sequence data are readily compared among laboratories and lend themselves to electronic storage and distribution. Furthermore, MLST can reduce the need to transport live bacteria, since nucleotide sequence determination from PCR products can be achieved from killed-cell suspensions, purified DNA, or clinical material. A World Wide Web site for the storage and exchange of data and protocols for MLST has been established (http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk). While MLST is particularly suited to long-term and global epidemiology, as it identifies variation which is accumulating slowly within a population (20), the data can be used in the investigation of individual outbreaks, especially when MLST data are combined with other data, such as the nucleotide sequences of genes encoding antigens (6, 9).

Here, an MLST scheme for C. jejuni is described. The system is based on the nucleotide sequences of seven housekeeping loci and was established by the examination of 194 isolates obtained from a variety of sources. A total of 155 distinct sequence types (STs) were identified, which were resolved into 62 clonal lineages or complexes. There was evidence for extensive horizontal genetic exchange, including import of alleles from at least two other Campylobacter species, including C. coli. Further analysis indicated that C. jejuni had a weakly clonal population structure and that some complexes were associated with particular Penner HS serotypes. These results provide a basis for further investigations of the epidemiology and population genetics of C. jejuni by MLST.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Campylobacter isolates.

C. jejuni isolates were obtained from the collection held at Preston Public Health Laboratory, Preston, United Kingdom (35), and included isolates from cases of human campylobacteriosis, livestock, and the environment. Reference isolates for the Penner heat-stable antigen serotyping scheme (28) were donated to the Preston Public Health Laboratory culture collection by J. Penner and are available from the National Collection of Type Cultures and American Type Culture Collection. Eleven further isolates were obtained from a collection held in The Netherlands at the Research Laboratory for Infectious Diseases, at the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment, and at the Department of Bacteriology, Institute for Animal Science and Health. Of these, the nonhuman isolates were obtained from geographically dispersed farms in The Netherlands (11), and human isolates were obtained from a case-control study among general practitioners in The Netherlands. The total of 194 isolates comprised 79 from human cases of campylobacteriosis, 38 from livestock, 34 from environmental locations, 3 from milk, and 40 of the reference isolates for the Penner serotyping scheme. Of the human isolates, 75 were from cases which occurred in the United Kingdom during 1990 and 1991, 3 were isolated in the Netherlands during 1997 and 1998, and 1 was obtained from a case in Australia during 1998. The livestock isolates included 34 from chickens, 3 from cattle, and 1 from a duck (including 24 isolates from the United Kingdom, 5 from The Netherlands, and 5 from New Zealand, all isolated during the 1990s). The three isolates from milk were obtained in the United Kingdom during 1991, and all of the environmental isolates were from the sand of bathing beaches (United Kingdom, 1994 and 5), with the exception of one, which was from water (United Kingdom, 1991).

Culture of isolates and preparation of chromosomal DNA.

All of the bacterial isolates included had been maintained with minimal passages at −70°C in 20% (vol/vol) glycerol in brain heart infusion broth, and consequently none of the genetic variation studied was likely to have been introduced during storage. Prior to DNA extraction, cultures were removed from storage and allowed to thaw at room temperature. For each isolate, a blood agar plate was spread for discrete colonies and incubated at 37°C for 72 h under microaerobic conditions (5). Chromosomal DNA was extracted using an Isoquick kit (Microprobe Corporation) or Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

Choice of loci.

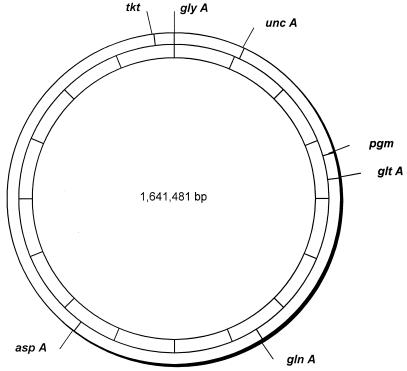

A number of candidate loci, encoding enzymes responsible for intermediary metabolism, were identified by searching the C. jejuni genome database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_jejuni/) (26) with gene sequences from other bacteria. Suitable genes were then chosen on the basis of a number of criteria, including chromosomal location, suitability for primer design, and sequence diversity in pilot studies. The following seven loci were chosen for the MLST scheme (protein products are shown in parentheses): aspA (aspartase A), glnA (glutamine synthetase), gltA (citrate synthase), glyA (serine hydroxymethyltransferase), pgm (phosphoglucomutase), tkt (transketolase), and uncA (ATP synthase α subunit). The chromosomal locations of these housekeeping loci suggested that it was unlikely for any of them to be coinherited in the same recombination event, as the minimum distance between loci was 70 kb (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Chromosomal locations of MLST loci. The positions of the seven loci are shown on a map of the C. jejuni chromosome derived from the genome sequence of isolate NCTC 11168 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_jejuni/). The 1,641,481-bp genome is divided into 10 segments (indicated on the inner circle), with each segment representing 164,148 bp.

Amplification and nucleotide sequence determination.

PCR products were amplified with oligonucleotide primer pairs designed from the published C. jejuni sequence (26). A range of primers were tested, with those shown in Table 1 providing reliable amplification from a diverse range of samples (additional dideoxyoligonucleotide primers are described at http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk). Each 50-μl amplification reaction mixture comprised ∼10 ng of campylobacter chromosomal DNA, 1 μM each PCR primer, 1× PCR buffer (Perkin-Elmer Corp.), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.8 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 1.25 U of Amplitaq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Corp.). The reaction conditions were denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, primer annealing at 50°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, for 35 cycles. The amplification products were purified by precipitation with 20% polyethylene glycol–2.5 M NaCl (7), and their nucleotide sequences were determined at least once on each DNA strand using internal nested primers (Table 1) and BigDye Ready Reaction Mix (PE Biosystems) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Unincorporated dye terminators were removed by precipitation of the termination products with 95% ethanol, and the reaction products were separated and detected with an ABI Prism 3700 or an ABI Prism 377 automated DNA sequencer (PE Biosystems). Sequences were assembled from the resultant chromatograms with the STADEN suite of computer programs (32).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers for Campylobacter MLST

| Locus | Dideoxyoligonucleotide primer

|

Amplicon size (bp) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function | Name and sequence

|

|||

| Forward | Reverse | |||

| asp | Amplification | asp-A9, 5′-AGT ACT AAT GAT GCT TAT CC-3′ | asp-A10, 5′-ATT TCA TCA ATT TGT TCT TTG C-3′ | 899 |

| Sequencing | asp-S3, 5′-CCA ACT GCA AGA TGC TGT ACC-3′ | asp-S6, 5′-TTA ATT TGC GGT AAT ACC ATC-3′ | ||

| gln | Amplification | gln-A1, 5′-TAG GAA CTT GGC ATC ATA TTA CC-3′ | gln-A2, 5′-TTG GAC GAG CTT CTA CTG GC-3′ | 1,262 |

| Sequencing | gln-S3, 5′-CAT GCA ATC AAT GAA GAA AC-3′ | gln-S6, 5′-TTC CAT AAG CTC ATA TGA AC-3′ | ||

| glt | Amplification | glt-A1, 5′-GGG CTT GAC TTC TAC AGC TAC TTG-3′ | glt-A2, 5′-CCA AAT AAA GTT GTC TTG GAC GG-3′ | 1,012 |

| Sequencing | glt-S1, 5′-GTG GCT ATC CTA TAG AGT GGC-3′ | glt-S6, 5′-CCA AAG CGC ACC AAT ACC TG-3′ | ||

| gly | Amplification | gly-A1, 5′-GAG TTA GAG CGT CAA TGT GAA GG-3′ | gly-A2, 5′-AAA CCT CTG GCA GTA AGG GC-3′ | 816 |

| Sequencing | gly-S3, 5′-AGC TAA TCA AGG TGT TTA TGC GG-3′ | gly-S4, 5′-AGG TGA TTA TCC GTT CCA TCG C-3′ | ||

| pgm | Amplification | pgm-A7, 5′-TAC TAA TAA TAT CTT AGT AGG-3′ | pgm-A8, 5′-CAC AAC ATT TTT CAT TTC TTT TTC-3′ | 1,150 |

| Sequencing | pgm-S5, 5-GGT TTT AGA TGT GGC TCA TG-3′ | pgm-S2, 3′-TCC AGA ATA GCG AAA TAA GG-3′ | ||

| tkt | Amplification | tkt-A3, 5′-GCA AAC TCA GGA CAC CCA GG-3′ | tkt-A6, 5′-AAA GCA TTG TTA ATG GCT GC-3′ | 1,102 |

| Sequencing | tkt-S5, 5′-GCT TAG CAG ATA TTT TAA GTG-3′ | tkt-S4, 5′-ACT TCT TCA CCC AAA GGT GCG-3′ | ||

| unc | Amplification | unc-A7, 5′-ATG GAC TTA AGA ATA TTA TGG C-3′ | unc-A2, 5′-GCT AAG CGG AGA ATA AGG TGG-3′ | 1,120 |

| Sequencing | unc-S5, 5′-TGT TGC AAT TGG TCA AAA GC-3′ | unc-S4, 5′-TGC CTC ATC TAA ATC ACT AGC-3′ | ||

Allele and ST assignment.

For each locus, distinct allele sequences were assigned arbitrary allele numbers in order of identification; these were in-frame internal fragments of the gene which contained an exact number of codons. Each isolate was therefore designated by seven numbers, constituting an allelic profile or ST. The data were deposited in a database accessible on the Internet at http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk/. The STs were identified by arbitrary numbers assigned in order of description (e.g., ST-1). New sequences were assigned allele numbers and isolates were assigned their STs by interrogating the database. Allele numbers for new sequences and ST numbers for new allelic profiles are available by submission to the database.

The STs were grouped into lineages or clonal complexes using the program BURST (E. J. Feil and M.-S. Chan, available at http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk). The members of a lineage were defined as groups of two or more independent isolates with an ST that shared identical alleles at four or more loci. Each lineage was named after the ST identified as the putative founder of the group by BURST, followed by the word “complex” (e.g., ST-21 complex).

Phylogenetic analyses.

The degree of clonality within the data set was estimated by measuring the index of association (IA) and was calculated for all STs and for a subset of STs representative of each lineage with a program written by J. Maynard Smith (23). The relationships among the STs in a given complex were investigated by constructing a distance matrix of allelic mismatches with the program MLD DISTANCE MATRIX (K. A. Jolley). Each locus difference was treated identically in that no relationships among the different alleles were assumed. The distance matrix was then visualized by Split decomposition analysis using SPLITSTREE version 3.1 (14, 21). Where necessary, higher resolution of the splits graph was obtained by progressively pruning resolved branches, and the graphs were annotated by reference to the allelic profiles. Other data analyses, including calculation of dN/dS, were performed using the MEGA suite of programs (18). All of the programs were available for electronic downloading (http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk, http://bibserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/splits, and http://evolgen.biol.metro-u.ac.jp/MEGA/).

RESULTS

Diversity of housekeeping genes.

The alleles defined for the MLST scheme were between 402 bp (gltA) and 507 bp (glyA) in length, and between 27 (gltA and unc) and 46 (pgm) alleles were present per locus. The proportion of variable sites present in the MLST alleles ranged from 9.2% (pgm) to 21.2% (tkt). In part, this was due to the polymorphisms present in a minority of alleles which were divergent (11 to 15% nucleotide sequence difference) from all other allele sequences. Such alleles were observed at least once for each of the MLST loci and were present in a total of 11 isolates, which had divergent alleles at between one and six loci. Searches of the GenBank database established that two of these, at the gltA locus, were very similar (97% nucleotide sequence identity) to the sequence of this gene from C. coli. When the divergent alleles were removed from analysis, the remaining allele sequences had between 5.2% (aspA) and 11.8% (pgm) variable sites (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Genetic diversity at C. jejuni MLST locia

| Locus | Fragment size (bp) | No. of alleles | No. of variable sites | % Variable sites | dN/dS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aspA | 477 | 37 (35) | 67 (25) | 14 (5.2) | 0.055 (0.049) |

| glnA | 477 | 39 (36) | 69 (30) | 14.4 (6.3) | 0.045 (0.071) |

| gltA | 402 | 27 (25) | 63 (32) | 15.7 (8) | 0.059 (0.057) |

| glyA | 507 | 37 (35) | 107 (59) | 21.1 (11.6) | 0.058 (0.057) |

| pgm | 498 | 46 (45) | 108 (59) | 21.7 (11.8) | 0.048 (0.038) |

| tkt | 459 | 37 (32) | 98 (48) | 21.3 (10.5) | 0.033 (0.037) |

| uncA | 489 | 27 (25) | 91 (41) | 18.6 (8.4) | 0.028 (0.036) |

The values in parentheses exclude alleles which were likely to have originated in other species.

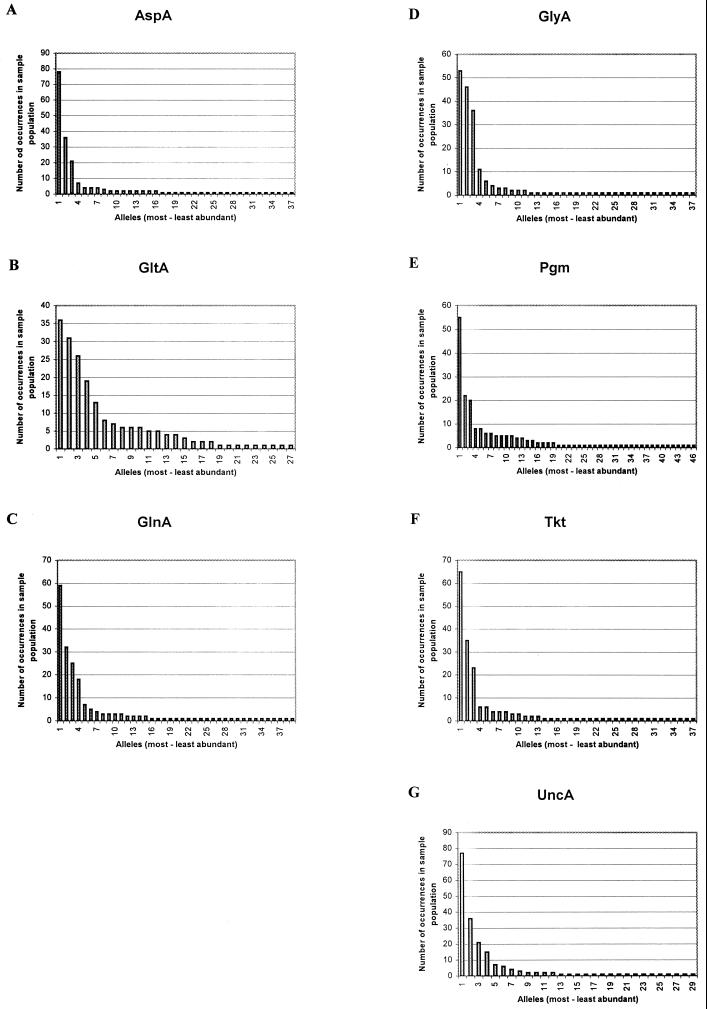

The proportion of nucleotide changes which changed the amino acid sequence was calculated and indicated by dN (nonsynonymous base substitutions), and the proportion of nucleotide changes which did not change the amino acid sequence was indicated by dS (synonymous base substitutions). The dN/dS ratios were calculated for all seven loci and were much less than 1 whether or not the more divergent alleles were included in the analysis (Table 2). The frequency that each allele occurred in the sample population is shown in Fig. 2; in each case several alleles predominated, with the remainder observed in one or two isolates.

FIG. 2.

Allele frequencies in the sample population. For each of the seven loci (A to G), the number of times that each allele occurs in the isolate collection is shown. The frequencies are shown in the order of most to least abundant.

STs and lineages.

There were a total of 155 STs among the 194 isolates examined, 140 (90%) of which were present only once, with the most common ST (ST-21) occurring eight times in the dataset. Assignment of the STs to lineages established that 51 STs were both unique and unrelated to any others (data are available at http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk/). The remaining isolates were assigned to 11 complexes: the ST-21 complex was the largest, with 56 members; the ST-45 complex had 23 members; and the ST-179 complex comprised 7 STs. There were two lineages with three member STs (two lineages) and six lineages with two members (Table 3). The IA for the complete data set was 2.016, with a value of 0.5671 obtained when only one representative of each lineage was included.

TABLE 3.

C. jejuni lineages

| Lineage | ST | Isolate

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Namea | Source | Yr isolated | Country | Penner serotypec | ||

| ST-21 complex | 13 | P02 (ATCC 43430) | Calf | 2 | ||

| 2692 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | ||

| 18 | 313 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 19 | 2167 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 304 | Chicken | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | ||

| 307 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | ||

| 3907 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 1 | ||

| 319 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | ||

| 316 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | ||

| 20 | 3618 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 21 | 2248 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 3616 | Milk | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | ||

| 2567 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | ||

| 2836 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | NTd | ||

| 3175 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | ||

| 3617 | Milk | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | ||

| 2269 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | ||

| 1576 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | NT | ||

| 31 | 321 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 32 | 322 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 33 | 333 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 35 | 327 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 36 | 1741 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | 4c | |

| 38 | 1835 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | NT | |

| 43 | NCTC 11168b | Human | 1977 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 44 | 161Hr | Chicken | 1998 | The Netherlands | 1, 44 | |

| 47 | 79203 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 10 | |

| 79202 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 10 | ||

| 79204 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 10 | ||

| 48 | Cy6412 | Cattle | 1998 | The Netherlands | ||

| 50 | 2817 | Water | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 314 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 1 | ||

| 1951 | Chicken | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | ||

| 309 | Chicken | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | ||

| 53 | 2399 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 3281 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | ||

| 2457 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | ||

| C356 | Chicken | 1990 | The Netherlands | 2 | ||

| 61 | 1589 | Cattle | 1991 | The Netherlands | 13 | |

| 2018 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | 4c | ||

| 1739 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | 4c | ||

| 2019 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | 4c | ||

| 2037 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | 4c | ||

| 67 | 2473 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 69 | 79201 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 72 | 1441 | Cattle | 1993 | New Zealand | 13, 50 | |

| 75 | 3615 | Milk | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 76 | 1434 | Chicken | 1993 | New Zealand | 2 | |

| 79 | 3748 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 4 | |

| 86 | P4 (NCTC 12561) | 4 | ||||

| 1939 | Chicken | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | ||

| 90 | 3897 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 91 | 79178 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 4 | |

| 93 | 1529 | Human | 1993 | United Kingdom | NT | |

| 1564 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | NT | ||

| 1715 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | 4c | ||

| 2017 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | 4c | ||

| 2035 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | 4c | ||

| 3222 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 4 | ||

| 98 | 79238 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 4 | |

| 102 | 337 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 103 | 1656 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | ||

| 104 | 3782 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 4 | |

| 105 | 3174 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 107 | 2945 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 108 | 2879 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 110 | 2582 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 111 | 2546 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 112 | 2255 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 114 | 2160 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 118 | 1950 | Chicken | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 119 | 2241 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 120 | 2856 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 44 | |

| 124 | 317 | Chicken | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 125 | 326 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 135 | 2386 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 136 | 79205 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 10 | |

| 141 | 2272 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 142 | 2325 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 4 | |

| 156 | P50 (ATCC 43465) | Human | 1983 | 50 | ||

| 157 | 330 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 159 | 1827 | Human | 1992 | United Kingdom | NT | |

| 161 | 3827 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 4 | |

| 164 | 3550 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 165 | 1953 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| 167 | 2529 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 169 | 2844 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 170 | 2987 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| ST-45 complex | 1 | P9 (ATCC 43437) | Goat | 9 | ||

| 2 | P12 (ATCC 43440) | Human | 12 | |||

| 6 | P27 (ATCC 43450) | Human | 27 | |||

| 8 | P33 (ATCC 43454) | Human | 33 | |||

| 10 | P55 (ATCC 43468) | Human | 55 | |||

| 25 | 1429 | Chicken | 1991 | 9 | ||

| 45 | 3057 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 60 | |

| P7 (ATCC 43435) | Human | 7 | ||||

| 66 | 3109 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 6 | |

| 68 | 3105 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 4, 16, 50 | |

| 70 | 79228 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 38 | |

| 77 | 2656 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 27 | |

| 88 | P42 (ATCC 43461) | Human | Canada | 42 | ||

| 94 | 3110 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 60 | |

| 95 | 3188 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | NT | |

| 97 | 1436 | Chicken | 1993 | New Zealand | NT | |

| 109 | 2809 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 55 | |

| 128 | P38 (ATCC 43458) | Human | 38 | |||

| 137 | P45 (ATCC 43464) | Human | 45 | |||

| 146 | 87034 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | NT | |

| 163 | 2924 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 4, 13, 50 | |

| 168 | 2897 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 3, 37 | |

| 171 | 3108 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 6 | |

| 173 | 3052 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 4, 16, 50 | |

| ST-179 complex | 80 | 79125 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 2 |

| 99 | 79129 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 5 | |

| 100 | 79207 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 117 | 79045 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 5 | |

| 152 | 79371 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 153 | 79372 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 2 | |

| 179 | 78972 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 5 | |

| ST-22 complex | 16 | P19 (ATCC 43446) | Human | 19 | ||

| 22 | 3201 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 19 | |

| 1997–1591 | Human | 1997 | The Netherlands | 19 | ||

| 78 | 3779 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 19 | |

| ST-177 complex | 81 | 79260 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | 55 |

| 144 | 79308 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | NT | |

| 177 | 79309 | Sand | 1994–1995 | United Kingdom | NT | |

| ST-17 complex | 14 | P11 (ATCC 43439) | Human | Canada | 11 | |

| 17 | 3157 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 11 | |

| 2475 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 11 | ||

| ST-51 complex | 27 | P37 (ATCC 43457) | Human | 37 | ||

| 51 | 160H | Chicken | 1998 | The Netherlands | ||

| ST-65 complex | 34 | 335 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| 65 | 323 | Chicken | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| ST-52 complex | 52 | c2143 | Chicken | 1991 | The Netherlands | |

| 172 | 2320 | Human | 1991 | United Kingdom | 10 | |

| ST-125 complex | 125 | 326 | Human | 1990 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| 135 | 2386 | Chicken | 1991 | United Kingdom | 1 | |

| ST-130 complex | 130 | P64 (ATCC 49302) | Human | 64 | ||

| 162 | P65 (ATCC 49303) | Not stated | 65 | |||

Where appropriate the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) or National Collection of Type Cultures (NCTC) designation is also given. Names beginning with P indicate reference isolates for the Penner serotyping scheme.

Campylobacter isolate for which the complete genome sequence is available at http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_jejuni/.

From reference 28.

NT, nontypeable.

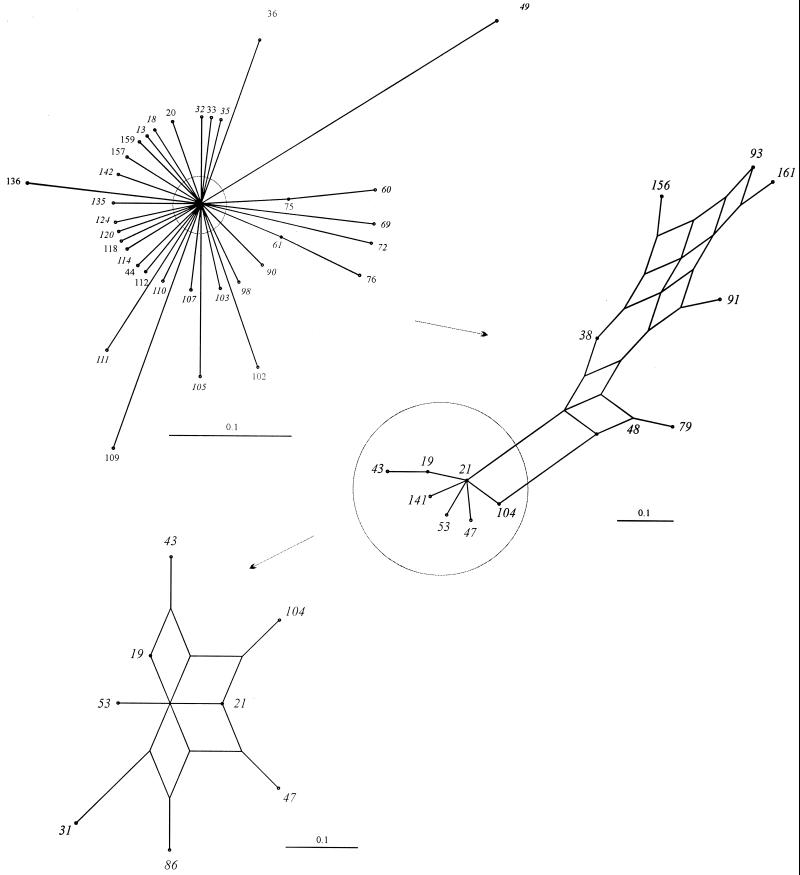

Interrelationships of members of the ST-21 complex.

The relationships among members of the ST-21 complex were visualized by an annotated splits graph of a distance matrix generated by pairwise comparisons of the allelic profiles (Fig. 3). The unresolved splits graph including all members of the complex is shown at the top left of Fig. 3. The outer branches were then pruned to show a partially resolved network, which was further pruned to resolve completely the center of the graph. Consistent with the lineage assignment by BURST, this placed the predicted founder ST at a central position of the split graph. The relationships among other members of the group were assessed by examining the number of nodes (representing the number of changes) between two isolates. For example, in the central region of the graph, ST-21 and ST-19 are separated by one node, representing one allele change between the two. Their STs are 2-1-1-3-2-1-5 and 2-1-5-3-2-1-5, respectively. ST-21 and ST-31 were separated by two nodes and differed by two alleles (ST-31 is 2-20-12-3-2-1-5).

FIG. 3.

Splits graphs showing the interrelationships of members of ST-21 complex. Progressive pruning of branches to improve resolution is indicated by the circles and arrows. The completely resolved region (bottom left) derived from the center of the unpruned graph contains the most abundant members of the complex and the predicted founder of the lineage, ST-21.

Relationships of lineage, source, and serotype.

Isolates belonging to the two largest lineages present in the data set, the ST-21 complex and ST-45 complex, had originated from a diversity of sources (Table 3). The ST-21 complex included 59 of the 79 human isolates studied (75%), 14 of the 34 chicken isolates (41%), 7 of the 33 sand isolates (21%), 3 of the 3 cattle isolates (100%), and 3 of the 3 milk isolates (100%). The ST-45 complex included 10 of the 79 human isolates (13%), 11 of the 34 chicken isolates (32%), and 2 of the 33 sand isolates (6%). Three Penner HS serotypes predominated in the ST-21 complex (HS1, 25%; HS2, 33%; and HS4, 8%), and some of the STs forming this lineage were homogenous for serotype (e.g., the six ST-19 isolates were all HS1, while the eight ST-21 isolates were all HS2 or non typeable), although these serotypes were also present in isolates exhibiting different STs. Conversely, the ST-45 complex contained a wide variety of serotypes and a number of cross-reactive isolates, but the two most common serotypes observed in the ST-21 complex, HS1 and HS2, were not present in the ST-45 complex. The remaining complexes comprised small numbers in the isolate collection and these were homogenous for serotype, with the exception of the seven ST-179 complex isolates which originated in sand and were HS2 or HS5 and two members of the ST-130 complex (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Unambiguous, discriminatory isolate characterization schemes are essential for epidemiological, population genetic, and evolutionary studies. Ideally, these schemes generate data that are relevant to all of these areas, but before the recent advent of high-throughput nucleotide sequence determination technology, this goal had proved elusive (19). There is a particular need for appropriate typing schemes for C. jejuni, as this common human pathogen (3) has extensive animal and environmental reservoirs and the relationships between disease-associated and animal or environmental populations remain to be fully elucidated. This study demonstrates that MLST (i) discriminates among C. jejuni isolates effectively and (ii) generates data that can be applied to the investigation of the population structure and evolutionary mechanisms in this organism. The advantages of MLST include high discrimination, reproducibility, simplicity of interpretation by using one technique rather than a combination of techniques, and the generation of data which are directly comparable among laboratories via the Internet (20). The ease with which the system can be transferred among laboratories was exploited in this study, with the sequence determinations being performed in two separate locations (Oxford and Bilthoven).

The seven loci chosen were a suitable basis for an MLST typing scheme, as they could be amplified and sequenced from isolates obtained from a wide variety of sources, were unlinked on the C. jejuni chromosome (Fig. 1), exhibited sufficient diversity to provide a high degree of resolution, and were not subject to positive selection, as demonstrated by the dN/dS ratios calculated for each locus (Table 2). The fact that the dN/dS ratios were much less than 1 demonstrates that there is selection against amino acid change (a dN/dS ratio of greater than 1 implies selection for amino acid changes). The nucleotide sequence determination for these loci was consistent with the results obtained previously from a number of phenotypic and genotypic studies of C. jejuni, which suggested that populations of this organism are highly diverse (35, 36). Some of this diversity was likely to have been imported recently from related species, with a potential donor, C. coli, identified for some of the more diverse sequences. When these likely importation events were excluded (Table 2), the C. jejuni sample exhibited nucleotide sequence diversity similar to that observed in Neisseria meningitidis (12, 15a, 20) and substantially greater than that seen in Streptococcus pneumoniae (8).

The housekeeping gene sequences provided evidence that horizontal genetic exchange has a major influence on the structure and evolution of Campylobacter populations, which was itself consistent with previous findings for the antigen genes of C. jejuni (10). The fall in the IA from 2, for the whole data set, to 0.57, when only one example of each lineage was included, was indicative of a weakly clonal population (22) which contained a number of clonal complexes of relatively recent evolutionary origin with no tree-like phylogenetic relationship with each other (12). The presence of the same allele in isolates of diverse origins and different lineages (for example, aspA allele number 2 in isolates from humans, sand, and poultry) supported this view, as did the fact that the majority of changes within the most common lineages were likely to be due to recombinational replacement rather than mutation.

The presence of apparent lineages in isolate collections of weakly clonal organisms may be amplified by sampling (23); for example, the presence of many isolates belonging to the ST-21 complex could have been a consequence of members of this complex being more likely to be associated with human infection. Alternatively, certain lineages might be associated with a particular niche, for example, the ST-179 complex, which contained environmental isolates (from sand of United Kingdom bathing beaches) (4). Further MLST analyses of appropriate isolate collections are necessary to address these questions more fully. However, the finding that human isolates cluster predominantly in the ST-21 complex, while chicken isolates have a broader distribution, suggests that it may be unlikely that the majority of the human strains come from chickens but that human strains may come from different sources like cattle, although the number of strains studied from cattle were low. A more detailed nucleotide sequence-based investigation of the relationships of organisms classified as different Campylobacter species is also warranted given the evidence for genetic exchange among these organisms.

A number of typing techniques have been applied to C. jejuni, with Penner HS typing, which is based on the lipopolysaccharide component of the outer membrane (28), being favored by many laboratories. The data presented here demonstrated that the Penner HS serotype was consistent and conserved in some lineages, (Table 3); for example, there was a correlation between Penner HS type and ST among some members of the ST-21 complex. However, the members of the ST-45 complex were highly diverse for Penner HS serotype (Table 3). These data are consistent with those reported earlier (25, 31, 35) and suggested the existence of a number of C. jejuni strains which were genetically and antigenically stable over the sampling period.

This data set provides a basis for the exploitation of MLST in the study of C. jejuni. The MLST approach is in principle applicable to any bacterial species, and while the oligonucleotide primers described here were not designed for characterization of other Campylobacter species, the evidence for interspecies horizontal genetic exchange between C. jejuni and at least one other Campylobacter species strongly suggests that this MLST system will be directly applicable to other Campylobacter species. The identification of alleles with gene sequences that were diverse from the majority of C. jejuni sequences may indicate disparity between microbiological and nucleotide sequence-based species classifications of these organisms, but additional data and analyses will be required to address these issues.

The MLST scheme provides a means for the investigation of disease outbreaks in both global and local contexts, permitting confirmation of suspected routes of transmission from the environment and livestock to humans. In addition, MLST data will assist in resolving broader issues such as the relationship of environmental to disease isolates at the population level, the structure of Campylobacter populations, the existence or otherwise of widely distributed lineages, and the extent of intra- and interspecies recombination. The Campylobacter MLST website is a freely accessible resource available to the community as a whole for the investigation of this important and as yet incompletely understood pathogen. Submission of data from other laboratories is welcomed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the United Kingdom Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (contract number OZ0604).

We are grateful to Birgitta Duim and Jaap Wagenaar, Department of Bacteriology, Institute for Animal Science and Health, Lelystad, The Netherlands, for providing the chromosomal DNA of the human and animal campylobacter isolates from The Netherlands.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman M, Zurth K, Morelli G, Torrea G, Guiyoule A, Carniel E. Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, is a recently emerged clone of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14043–14048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adak G K, Cowden J M, Nicholas S, Evans H S. The Public Health Laboratory Service national case-control study of primary indigenous sporadic cases of campylobacter infection. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;115:15–22. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altekruse S F, Stern N J, Fields P I, Swerdlow D L. Campylobacter jejuni—an emerging foodborne pathogen. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:28–35. doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolton F J, Surman S B, Martin K, Wareing D R A, Humphrey T J. Presence of Campylobacter and Salmonellae in sand from bathing beaches. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122:7–13. doi: 10.1017/s0950268898001915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolton F J, Wareing D R A, Skirrow M B, Hutchinson D N. Identification and biotyping of campylobacters. In: Board R G, Jones D, Skinner F A, editors. Identification methods in applied and environmental microbiology. London, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd.; 1992. pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bygraves J A, Urwin R, Fox A J, Gray S J, Russell J E, Feavers I M, Maiden M C J. Population genetic and evolutionary approaches to the analysis of Neisseria meningitidis isolates belonging to the ET-5 complex. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5551–5556. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5551-5556.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Embley T M. The linear PCR reaction: a simple and robust method for sequencing amplified rRNA genes. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1991;13:171–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1991.tb00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enright M, Spratt B G. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology. 1998;144:3049–3060. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feavers I M, Gray S J, Urwin R, Russell J E, Bygraves J A, Kaczmarski E B, Maiden M C J. Multilocus sequence typing and antigen gene sequencing in the investigation of a meningococcal disease outbreak. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3883–3887. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3883-3887.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrington C S, Thomson Carter F M, Carter P E. Evidence for recombination in the flagellin locus of Campylobacter jejuni: implications for the flagellin gene typing scheme. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2386–2392. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2386-2392.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heuvelink A E, Tilburg J J H C, Voogt N, van Pelt W, van Leeuwen W J, Sturm J M J, van de Giesen A W. Surveilance of zoonotic bacteria among farm animals (Dutch). RIVM-report 285859–009. Bilthoven, The Netherlands: RIVM; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes E C, Urwin R, Maiden M C J. The influence of recombination on the population structure and evolution of the human pathogen Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:741–749. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudson J A, Nicol C, Wright J, Whyte R, Hasell S K. Seasonal variation of Campylobacter types from human cases, veterinary cases, raw chicken, milk and water. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:115–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huson D H. SplitsTree: a program for analysing and visualising evolutionary data. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:68–73. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson C J, Fox A J, Jones D M, Wareing D R, Hutchinson D N. Associations between heat-stable (O) and heat-labile (HL) serogroup antigens of Campylobacter jejuni: evidence for interstrain relationships within three O/HL serovars. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2223–2228. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2223-2228.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Jolley K A, Kalmusova J, Feil E J, Gupta S, Musilek M, Kriz P, Maiden M C J. Carried meningococci in the Czech Republic: a diverse recombining population. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4492–4498. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.12.4492-4498.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ketley J M. Pathogenesis of enteric infection by Campylobacter. Microbiology. 1997;143:5–21. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konkel M E, Gray S A, Kim B J, Garvis S G, Yoon J. Identification of the enteropathogens Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli based on the cadF virulence gene and its product. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:510–517. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.510-517.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software for microcomputers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maiden M C J. High-throughput sequencing in the population analysis of bacterial pathogens of humans. Int J Med Microbiol. 2000;290:183–190. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maiden M C J, Bygraves J A, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell J E, Urwin R, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zurth K, Caugant D A, Feavers I M, Achtman M, Spratt B G. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maynard Smith J. The population genetics of bacteria. Proc R Soc London B. 1991;245:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maynard Smith J, Dowson C G, Spratt B G. Localized sex in bacteria. Nature. 1991;349:29–31. doi: 10.1038/349029a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maynard Smith J, Smith N H, O'Rourke M, Spratt B G. How clonal are bacteria? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4384–4388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nachamkin I, Allos B M, Ho T. Campylobacter species and Guillain-Barre syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:555–567. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nachamkin I, Ung H, Patton C M. Analysis of HL and O serotypes of Campylobacter strains by the flagellin gene typing system. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:277–281. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.277-281.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parkhill J, Wren B W, Mungall K, Ketley J M, Churcher C, Basham D, Chillingworth T, Davies R M, Feltwell T, Holroyd S, Jagels K, Karlyshev A V, Moule S, Pallen M J, Penn C W, Quail M A, Rajandream M A, Rutherford K M, van Vliet A H, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature. 2000;403:665–668. doi: 10.1038/35001088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peabody R, Ryan M J, Wall P G. Outbreaks of Campylobacter infection: rare events for a common pathogen. Communicable Dis Rep. 1997;7:R33–R37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penner J L, Hennessy J N, Congi R V. Serotyping of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli on the basis of thermostable antigens. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1983;2:378–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02019474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selander R K, Caugant D A, Ochman H, Musser J M, Gilmour M N, Whittam T S. Methods of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for bacterial population genetics and systematics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:837–884. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.5.873-884.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skirrow M B. Diseases due to Campylobacter, Helicobacter and related bacteria. J Comp Pathol. 1994;111:113–149. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(05)80046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slater E, Owen R J. Subtyping of Campylobacter jejuni Penner heat-stable (HS) serotype 11 isolates from human infections. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:353–357. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-4-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staden R. The Staden sequence analysis package. Mol Biotechnol. 1996;5:233–241. doi: 10.1007/BF02900361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suerbaum S, Maynard Smith J, Bapumia K, Morelli G, Smith N H, Kunstmann E, Dyrek I, Achtman M. Free recombination within Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12619–12624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker R I, Caldwee M B, Lee E, Guerry P, Trust T J, Ruiz-Palacios G M. Pathophysiology of Campylobacter enteritis. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:81–94. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.1.81-94.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wareing D. The significance of strain diversity in the epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni gastrointestinal infections. Ph.D. thesis. Preston, United Kingdom: University of Central Lancashire; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wassenaar T M, Newell D G. Genotyping of Campylobacter species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1–9. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.1.1-9.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]