Abstract

Background:

This practice-based study estimated the risk of tooth fractures and crack progression over three years, and correlated baseline patient-, tooth- and crack-level characteristics with these outcomes.

Methods:

209 National Dental Practice-Based Research Network dentists enrolled a convenience sample of 2,601 subjects with a cracked vital posterior tooth that were examined for at least one recall visit over three years. Data were collected at the patient-, tooth-, and crack-level at baseline, annual follow-up visits, and any interim visits. Associations between these characteristics and the subsequent same-tooth fractures and crack progression were quantified.

Results:

78 (3.0%; 95% CI: 2.4% – 3.7%) of the 2,601 teeth with crack(s) at baseline subsequently developed a fracture. 232 (12.3%; 95% CI: 10.9% – 13.8%) of 1,889 patients untreated prior to Y1 had some type of crack progression. Baseline tooth-level characteristics associated with tooth fracture: the tooth was maxillary, had a wear facet through enamel, a crack detectable with an explorer, on the facial surface, horizontal direction. Crack progression was associated with males and teeth having multiple cracks at baseline; teeth with a baseline facial crack were less likely to demonstrate crack progression. There was no commonality between characteristics associated with tooth fracture compared to characteristics associated with crack progression.

Conclusions:

Development of tooth fractures and crack progression over 3 years were rare occurrences. Specific characteristics were associated with the development of tooth fracture and crack progression, although none were common to both.

Practical Implications:

This information can aid dentists in assessing factors that place posterior cracked teeth at risk for adverse outcomes.

Keywords: Cracked teeth, tooth fracture, crack progression

Introduction:

Cracked teeth are highly prevalent in the adult population1 and present a diagnostic and treatment conundrum2 with roots in ancient times3. Deciding on the best treatment is much less clear for asymptomatic teeth than for teeth displaying symptoms2,4.

Localized pain during chewing or biting, unexplained sensitivity to cold, and pain on release of pressure are all diagnostic tests used to determine if a tooth is cracked5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Ancillary analyses proposed to identify cracks include visual inspection (particularly with magnification), transillumination and staining11,16,17, percussion, biting and thermal pulp tests8,11,13, radiography14,16, microscopy18 (14X-18X), ultrasound19, optical coherence tomography20, quantitative light-induced fluorescence (QLF)21 and quantitative percussion diagnostics (QPD)22–24.

While some teeth with cracks can remain symptom-free and intact for extended periods, the risk of not intervening at the appropriate time can result in symptoms or more-catastrophic adverse outcomes that render the tooth non-restorable5. The conundrum is that it is difficult for dentists to determine accurately which cracked teeth are likely to suffer from harmful sequela2.

Many cracked-tooth risk factors have been described in the literature, including age25, tooth location26,cuspal inclination27, presence and type of restoration15, restoration size28, presence of occlusal interferences12, bruxism29,surface crack lines30, and oral piercings31. However, these findings are based on case reports or personal observations, or studies with a low sample size. The Cracked Tooth Registry (CTR) in the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network (National Dental PBRN or the network, nationaldentalpbrn.org) was designed as the largest and most-comprehensive prospective clinical assessment of cracked teeth to ascertain their behavior over time and to correlate observable baseline characteristics to adverse outcomes, such as changes in symptoms, crack progression and tooth fracture.

In previous publications32–36 the following findings were described. Baseline data of the CTR showed that patients who clenched or ground their teeth and had a molar tooth with a distal crack that blocked transilluminated light were most likely to demonstrate symptoms. Of the 435 cracked teeth treated restoratively at baseline such that the presence of internal cracks could be determined, 89% (N=389) had at least one internal crack and 87% (N=340) of the internal cracks extended into the dentin.

Pain due to a cold stimulus, in contrast to biting pain and spontaneous pain, was the most common symptom exhibited by patients with a cracked tooth. Of the 2,858 teeth enrolled in the study at baseline, 1,040 (36%) were recommended for treatment, primarily restorative. The presence of caries, biting pain and evidence of a crack on a radiograph were strongly associated with recommendation for treatment. At the one-year follow-up of 2,531 patients (89% of 2,858 enrolled), almost one-third of the patients had a change in their pain symptoms, with decreases in pain being double that of increases (21% [N=391] vs 9% [N=164]. Decreases in symptoms were more than twice as common among teeth that were treated than those not treated (45% [N=111] vs. 19% [N=310]). Changes in pain symptoms, specifically increases in symptoms, were not associated with an increase in the number of cracks in the affected tooth.

The primary outcome of interest for this particular analysis was tooth fracture incidence, since this is the most significant adverse outcome related to cracked teeth inevitably requiring treatment and in some cases extraction. The objectives of this 3-year study were to: 1) estimate the 3-year risk of tooth fractures and crack progression; and 2) correlate baseline patient-, tooth- and crack-level characteristics with these outcomes during the three-year follow-up period.

Methods:

Prior publications have detailed the study procedures, including enrollment and data collection at baseline32 and subsequent follow-up visits35. Briefly, dentists in general practice in the network37 screened a convenience sample of subjects between 19 and 85 years old for the presence of at least one single, vital posterior tooth with at least one clinically observable external crack. Vitality of enrolled teeth was confirmed with cold e.g., refrigerant or ice, although other methods such as air, air/water spray, or electric pulp testing were also used. Upon enrollment, participating dentists selected and characterized one eligible cracked tooth in each subject. Each practice consented and enrolled as many eligible subjects as they could in eight weeks, up to a maximum of 20 subjects. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the lead investigators (TH & JF), as well as the IRBs for the six network regions, reviewed and approved the study. Patient enrollment proceeded in two phases: a pilot with 183 patients from 12 practices from April-July 2014, followed by a main launch from October 2014-April 2015.

Data collection training materials were developed for the participants and included the following definitions:

- Crack: An obvious break of the external contiguous structure of the tooth, but involves no loss of tooth structure (e.g., lost cusp).

- Partial tooth fracture: the loss of a portion of tooth structure coronal to the periodontal attachment.

- Complete tooth fracture: a fracture that includes both the coronal and radicular tooth structure below the periodontal attachment (e.g., a fracture that renders the tooth non-restorable).

Since partial or complete tooth fractures were outcome measures, cracked teeth with fractures at baseline were ineligible. Various patient-, tooth- and crack-level characteristics were collected, including the presence and type of pain (spontaneous, cold, biting), as well as treatment recommendations for patient’s teeth. Data forms are publicly available at [http://nationaldentalpbrn.org/study-results/cracked-tooth-registry.php].

Patients were requested to return to their dentist annually for three years (Y1 – Y3). Any visit after baseline (Y0) and before the first annual recall (Y1) during which the cracked tooth was treated was recorded as an interim visit, and appropriate forms filled out. The Data Coordinating Center (DCC) notified the dental offices six months in advance of patient recall dates, and the offices sent reminders to the patients. Specific tracking procedures were used by the DCC for any patients the practices could not contact. Patients and practitioners received a nominal remuneration for the baseline and annual recall visits.

Recall visits were usually coincident with routine visits, billed to the patient’s insurance. A six-month window was permitted for the first two annual recall visits, but the window was opened for Y3 to maximize final recall visits, with the result that some patients had 22 months in between the last 2 recall visits. However, the follow-up time between Y2 and Y3 visits was virtually the same as between earlier recall windows (12.4 months, IQ 11.6–14.3). The same data collected at enrollment (Y0) were collected at each yearly recall visit, including treatments recommended and performed. Overall, 209 practitioners enrolled 2,858 patients between 04/2014 and 04/015; Y3 visit dates ranged 03/2017 to 12/2018.

Analysis.

The primary outcomes were whether over the 3-year period: (1) the cracked tooth developed a partial or complete fracture; or (2) there was progression of cracks. Although both outcomes were evaluated at each annual recall, the interest was the 3-year risk of these outcomes. Specifically, after a tooth developed a fracture, it was censored, so subsequent fractures were not analyzed. We did not perform sequential analysis, e.g., did Y1 fractures predict Y2, because the objective was to identify baseline characteristics that predicted failure or crack progression within 3 years. Crack progression was defined as either an increase in the number of cracks or an increase in the number of surfaces involved in a crack. As crack progression could only be ascertained on non-treated teeth, teeth treated before Y1 (namely, at Y0 or an interim visit before Y1) were excluded from those analyses. A third outcome was whether crack progression was a precursor, or predictor, of subsequent tooth fracture. Descriptive statistics were calculated for continuous variables.

Frequencies were obtained separately according to whether a cracked tooth developed a fracture and whether there was any crack progression. In a univariable fashion, each patient-, tooth-, and crack-level characteristic was entered into a logistic regression model, one for development of fractures and one for crack progression. Each model used a generalized estimating equation (GEE) to adjust for the clustering of patients within the practice, implemented using PROC GENMOD in SAS with the CORR=EXCH option. All characteristics with p<0.10 after adjusting only for the clustering of patients within the practice were entered into a full model. This was followed with backward elimination to identify independent associations, separately, for the development of tooth fracture and crack progression, removing variables until all remaining variables in each model had p<0.05. After the development of these two models, the association of crack progression with future tooth fracture was similarly assessed. All odds ratios (OR) and p-values reported were adjusted for the clustering of patients within practitioners with GEE. All analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS v9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC).

RESULTS

A total of 2,601 patients (91% of 2,858 enrolled) from 199 practices attended at least one recall visit. Of the 2,601, 2,507 (96%) attended Y1, 2,236 (86%) attended Y2, 2,079 (80%) attended Y3, and 1,912 (74%) attended all three annual recall visits. Overall, 712 (27%) of the 2,601 were treated prior to Y1, leaving 1,889 patients to assess for crack progression. The mean age of the 2,601 patients was 54 years (SD = 11.7). The majority were female (64%; N = 1,653), non-Hispanic white (85%; N = 2,190), had some dental insurance (78%; N = 2,017), or had a bachelor’s degree or higher (53%; N = 1,365). Approximately 44% (N=1,154) were symptomatic at baseline, meaning they had cold, biting or spontaneous pain. The distribution of these characteristics was virtually identical among both the total cohort with at least one annual recall (n=2,601), and those available for crack progression assessment (n=1,889), with the exception that fewer teeth in the latter cohort were symptomatic (37%; N = 699) compared to the former (44%; N= 1,145) (p < 0.001).

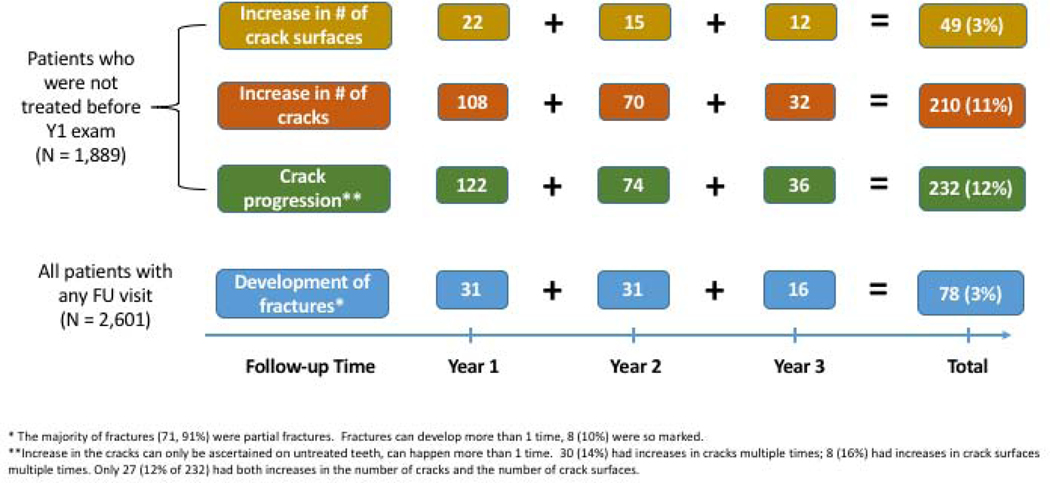

Overall, 78 (3%) of the 2,601 cracked teeth developed a fracture after baseline, and 232 (12% of 1,889 teeth not treated before Y1) had some type of crack progression after baseline (Figure 1 shows timing). 301 cracked teeth had an outcome of interest: 223 (74%) showed only crack progression, 69 (23%) showed only fractures, and 9 (3%) had both crack progression and a fracture. Tables 1–3 present the characteristics that were analyzed for associations with the development of fractures and with progression of cracks.

Figure 1:

Timing of fracture development and crack progression.

Table 1.

Patient-level characteristics of subjects with a cracked tooth at baseline according to whether fractures developed or whether there was any crack progression1 during 3 years of follow-up (FU).

| Baseline patient characteristics | All patients with any FU visit (N = 2,601) | Patients who developed a tooth fracture (N = 78) | Patients who were not treated before Y1 exam (N = 1,889) | Crack progressed (N = 232) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | N | Row %3 | N | N | Row %3 | |

|

| ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1,653 | 43 | 3% | 1,206 | 124 | 10% |

| Male | 947 | 35 | 4% | 682 | 91 | 13% |

| cluster adjusted p 4 | P = 0.12 | P = 0.01 | ||||

| Race 5 -ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 2,190 | 63 | 3% | 1,577 | 186 | 12% |

| Black | 118 | 2 | 2% | 83 | 5 | 6% |

| Asian | 46 | 2 | 4% | 37 | 4 | 11% |

| Hispanic | 162 | 7 | 4% | 126 | 14 | 11% |

| Other | 51 | 4 | 8% | 42 | 3 | 7% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.4 | P = 0.5 | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| < 35 | 165 | 3 | 2% | 118 | 6 | 5% |

| 35 – 44 | 387 | 9 | 2% | 272 | 39 | 14% |

| 45 – 54 | 744 | 19 | 3% | 540 | 62 | 11% |

| 55 – 64 | 838 | 25 | 3% | 599 | 68 | 11% |

| 65 and older | 466 | 22 | 5% | 359 | 40 | 11% |

| cluster adjusted p [trend] | P = 0.03 | P = 0.6 | ||||

| Dental insurance | ||||||

| None | 584 | 20 | 3% | 462 | 49 | 11% |

| Any | 2,017 | 58 | 3% | 1,427 | 166 | 12% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.5 | P = 0.6 | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| < Bachelor’s degree | 1,221 | 38 | 3% | 924 | 95 | 10% |

| Bachelor’s or higher | 1,365 | 40 | 3% | 953 | 119 | 12% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.8 | P = 0.8 | ||||

| Region | ||||||

| Western | 379 | 13 | 3% | 248 | 36 | 15% |

| Midwest | 340 | 11 | 3% | 220 | 38 | 17% |

| Southwest | 493 | 15 | 3% | 378 | 35 | 9% |

| South Central | 512 | 14 | 3% | 378 | 32 | 8% |

| South Atlantic | 445 | 14 | 3% | 346 | 24 | 7% |

| Northeast | 432 | 11 | 3% | 319 | 50 | 16% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.98 | P = 0.3 | ||||

| Symptomatic | ||||||

| No | 1,447 | 39 | 3% | 1,190 | 134 | 11% |

| Yes | 1,154 | 39 | 3% | 699 | 81 | 12% |

| cluster adjusted p | P= 0.2 | P = 0.8 | ||||

Crack progression: Increases in number or cracks or number of surfaces on a crack involved in the crack.

Column Ns not summing to column total N above due to missing data.

Percent with column heading within level of patient characteristic.

Significance of differences in proportions adjusted only for the clustering of patients within the practitioner using GEE.

Race groups are all non-Hispanic.

Table 3.

Crack-level characteristics of subjects with a cracked tooth at baseline according to whether fractures developed or whether there was any crack progression1 during 3 years of follow-up (FU).

| Baseline crack-level characteristics | All patients with any FU visit (N = 2,601) | Patients who developed a tooth fracture (N = 78) | Patients who were not treated before Y1 exam (N = 1,889) | Crack progressed (N = 232) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | N | Row %3 | N | N | Row %3 | |

|

| ||||||

| Has at least 1 crack that … | ||||||

| … stained | 2,118 | 67 | 3% | 1,541 | 179 | 12% |

| None stained | 483 | 11 | 2% | 348 | 36 | 10% |

| cluster adjusted p 4 | P = 0.3 | P = 0.4 | ||||

| … detectable with an explorer | 1,811 | 64 | 4% | 1,279 | 141 | 11% |

| None detectable with an explorer | 790 | 14 | 2% | 610 | 74 | 12% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.006 | P = 0.2 | ||||

| … blocked transilluminated light | 1,724 | 57 | 3% | 1,226 | 162 | 13% |

| None blocked transilluminated light | 877 | 21 | 2% | 663 | 53 | 8% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.2 | P = 0.2 | ||||

| … connected with a restoration | 1,909 | 65 | 3% | 1,366 | 169 | 12% |

| None connected with a restoration | 692 | 13 | 2% | 523 | 46 | 9% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.04 | P = 0.05 | ||||

| … connected with another crack | 111 | 7 | 6% | 69 | 9 | 13% |

| None connected with another crack | 2,490 | 71 | 3% | 1,820 | 206 | 11% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.14 | P = 0.5 | ||||

| … crack extended to root | 266 | 8 | 3% | 207 | 24 | 12% |

| None extended to root | 2,335 | 70 | 3% | 1,682 | 191 | 11% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.9 | P = 0.9 | ||||

| Crack directions | ||||||

| … in horizontal direction | 805 | 35 | 4% | 556 | 76 | 14% |

| None in horizontal direction | 1,796 | 43 | 2% | 1,333 | 139 | 10% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.01 | P = 0.3 | ||||

| … in vertical direction | 2,439 | 73 | 3% | 1,768 | 203 | 12% |

| None in vertical direction | 162 | 5 | 3% | 121 | 9 | 7% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.9 | P = 0.6 | ||||

| … in oblique direction | 254 | 14 | 6% | 185 | 18 | 10% |

| None in oblique direction | 2,347 | 64 | 3% | 1,704 | 197 | 12% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.045 | P = 0.11 | ||||

| … in more than 1 direction | 517 | 23 | 4% | 347 | 53 | 15% |

| All cracks in same direction | 2,084 | 55 | 3% | 1,542 | 162 | 11% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.06 | P = 0.2 | ||||

| Crack surfaces | ||||||

| … involved mesial | 1,168 | 33 | 3% | 814 | 105 | 13% |

| None involved mesial | 1,433 | 45 | 3% | 1,075 | 110 | 10% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.7 | P = 0.6 | ||||

| … involved occlusal | 1,164 | 39 | 3% | 821 | 117 | 14% |

| None involved occlusal | 1,437 | 39 | 3% | 1,068 | 98 | 9% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.4 | P = 0.004 | ||||

| … involved distal | 1,307 | 39 | 3% | 916 | 109 | 12% |

| None involved distal | 1,294 | 39 | 3% | 973 | 106 | 11% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.97 | P = 0.7 | ||||

| … involved facial | 1,306 | 51 | 4% | 899 | 110 | 12% |

| None involved facial | 1,295 | 27 | 2% | 990 | 105 | 11% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.009 | P = 0.07 | ||||

| … involved lingual | 1,330 | 43 | 3% | 958 | 117 | 12% |

| None involved lingual | 1,271 | 35 | 3% | 931 | 98 | 11% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.5 | P = 0.8 | ||||

| … involved >1 surface | 1,219 | 42 | 3% | 864 | 123 | 14% |

| None involved more than 1 surface | 1,382 | 36 | 3% | 1,025 | 92 | 9% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.2 | P = 0.005 | ||||

Crack progression: Increases in number or cracks or number of surfaces involved in the crack.

Column Ns not summing to column total N above due to missing data.

Percent with column heading (increased number of fractures or development of fractures) within level of tooth characteristic.

Significance of differences in proportions with column heading adjusted only for clustering of patients within practitioner using GEE.

Associations with fractures.

Characteristics independently associated with development of fractures after baseline (Table 4, “Final reduced model”) included a tooth located in the maxillary arch (OR = 1.8; 95% CI: 1.2 – 2.8), a wear facet through enamel at baseline (OR = 2.2; 95% CI: 1.4 – 3.3), having a crack at baseline that was detectable with an explorer (OR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.1 – 3.2), was in the horizontal direction (OR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.1 – 2.7), or that involved the facial surface at baseline (OR = 2.0; 95% CI: 1.2–3.3) (Table 4). Overall characteristics with p<0.1 after adjusting only for clustering of patients within the practice that were entered into the full model, but failed to be found significant in the final model, were increasing age of patients, teeth with multiple cracks, presence of a non-carious cervical lesion (NCCL), and cracks that connected with a restoration or ran in an oblique direction.

Table 4.

Independent associations between baseline characteristics and the two main outcomes (fracture and crack progression) measured in the Cracked Tooth Registry (CTR) study.

| Adjusted only for clustering | Full Model2 | Final reduced model3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | P1 | Odds Ratio | P | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P | |

|

|

|||||||

| Developed fracture(s) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Patient age (per 10 years) | 1.3 | 0.03 | 1.2 | 0.11 | x | x | x |

| Has 2 or more cracks | 1.8 | 0.01 | 1.0 | 0.97 | x | x | x |

| Maxillary | 1.5 | 0.09 | 1.7 | 0.04 | 1.8 | 1.2 – 2.8 | 1.10 |

| Wear facet thru enamel | 2.3 | 0.002 | 2.0 | 0.007 | 2.2 | 1.4 – 3.3 | 0.003 |

| Non-carious cervical lesion | 2.3 | 0.04 | 1.7 | 0.16 | x | x | x |

| Has crack that … is detectable with explorer | 2.0 | 0.006 | 1.7 | 0.036 | 1.9 | 1.1 – 3.2 | 0.02 |

| … connects with a restoration | 1.8 | 0.04 | 1.6 | 0.17 | x | x | x |

| … in horizontal direction | 1.9 | 0.01 | 1.6 | 0.16 | 1.7 | 1.1 – 2.7 | 0.04 |

| … in oblique direction | 2.0 | 0.045 | 1.3 | 0.4 | x | x | x |

| … in >1 direction | 1.7 | 0.06 | 1.0 | 0.98 | x | x | x |

| … involves facial surface | 1.9 | 0.009 | 1.8 | 0.02 | 2.0 | 1.2 – 3.3 | 0.006 |

|

| |||||||

| Crack progression | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Male patient | 1.4 | 0.01 | 1.4 | 0.02 | 1.4 | 1.1 – 1.8 | 0.02 |

| Has crack that … connects with restoration | 1.4 | 0.05 | 1.3 | 0.07 | x | x | x |

| … involves occlusal surface | 1.5 | 0.004 | 1.0 | 0.9 | x | x | x |

| … involves facial surface | 0.76 | 0.07 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.74 | 0.55 – 0.99 | 0.047 |

| … involves >1 surface | 1.6 | 0.005 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 1.2 – 2.3 | 0.004 |

P: Adjusted for clustering of patients within a practice using generalized estimating equations (GEE); all characteristics with P<0.1 are listed.

Full model: All characteristics with P<0.1 after adjusted only for clustering of patients with GEE were entered in the model.

Backwards elimination was used, removing variables until all remaining had p<0.05.

X:P>0.05, not retained in model.

Associations with crack progression.

Characteristics independently associated with crack progression after baseline (Table 4) were being male (OR = 1.4; 95% CI: 1.1 – 1.8) and having a crack at baseline that involved more than one surface (OR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.2 – 2.3), while having a crack involving the facial surface at baseline was less associated with crack progression (OR = 0.74; 95% CI: 0.55 – 0.99). Characteristics with p<0.1 after adjusting only for clustering of patients within the practice that were entered into the full model, but failed to be found significant in the final model, were cracks that at baseline were on the occlusal surface or that connected with a restoration.

Crack progression and fractures.

A total of 42 fractures were observed during the Y2 or Y3 examination. Among 1,674 teeth with no crack progression after baseline, 37 (2.2%) developed a tooth fracture. However, among 215 teeth with crack progression, 5 (2.3%) developed a tooth fracture. There was no difference either before adjustment for clustering (2% whether or not crack progression, P = 0.9), or after adjusting for clustering (P = 0.8).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published report describing the progression of cracks in teeth that have been systematically followed over three years, especially in a large cohort of nearly 3,000 patients. Most other longitudinal studies pertain to cracked teeth that were treated restoratively38,39,40 or endodontically41,42. Although there is a published study reporting on characteristics of cracked teeth, it is a cross-sectional investigation only15.

Several baseline characteristics were associated with tooth fracture incidence, including the tooth having a wear facet through the enamel. This is consistent with a cross-sectional observational study of 51 patients and 763 teeth, in which teeth with excursive interferences were 2.3 times more likely to have a concurrent crack12. An excursive interference implies parafunction from an oblique angle, creating shear or tensile forces that could lead to tooth fracture.

Cracks that ran in a horizontal direction were associated with tooth fracture incidence. Empirically, a fracture requires a connection between adjacent cracks so that a portion of the tooth breaks off. Since most cracks are vertical in direction, the presence of horizontal cracks could connect two longitudinal cracks.

Our results suggest that maxillary posterior teeth are more likely to fracture than mandibular posterior teeth. This was consistent with two previous studies26,43, but in contrast to others that found mandibular molars were more likely to have cracks38,44,45. Perhaps related to the predilection for maxillary posterior teeth to fracture was our finding that facial surfaces were more likely to lead to fracture. From an anatomical perspective, the lingual cusps of maxillary molars are more substantial structures than the facial cusps of maxillary molars46. A parafunctional lateral jaw movement could result in a working-side interference on the inner incline of the facial cusps, providing the oblique occlusal force to the smaller and presumably weaker facial maxillary molar cusps, resulting in their fracture. A study comparing intact maxillary molars to maxillary molars with diagnosed cracked tooth syndrome found that the cuspal incline of the cracked teeth was significantly steeper than the cuspal incline on the non-cracked teeth. Furthermore, finite element analysis revealed that the maximum tensile stress was greater in teeth with steeper cuspal inclines27. Cuspal incline was not assessed in the current study.

A final characteristic associated with tooth fracture was found in teeth that had a crack discernable with an explorer. A crack with enough displacement to be detectable when sliding an explorer tip over the tooth surface is likely to be indicative of a significant disruption of the tooth structure that will eventually lead to a fracture.

Crack progression was significantly more common in male patients, perhaps because males can generate a higher bite force compared to females47. Tooth-level characteristics associated with an increased likelihood of crack progression included teeth with more than one crack at baseline. Having multiple cracks at baseline may imply that a tooth is predisposed, and that conditions are present for further crack formation.

It was surprising that cracks that blocked transilluminated light were not predictive of either crack progression or tooth fracture. Transillumination is typically recommended to aid in the diagnosis of cracked teeth48, the implication being that the crack is extensive. However, cracks that block transilluminated light may remain within the enamel and therefore may not be indicative of a structurally compromised tooth18.

Unexpectedly, there was no association between characteristics that were predictive of crack progression and those predictive of tooth fracture. The only characteristic in common between these two main outcomes of interest in the final model was the presence of a crack on the facial surface, but its association with the outcome acted in opposite directions; a facial crack was associated with a reduced risk of crack progression, but an increased risk of tooth fracture. A possible explanation for this34, is that dentists are adept at identifying teeth at risk of further adverse outcomes and intervening with treatment, particularly restorative treatment, to intercept tooth fracture. This is supported by the fact that only 3% of cracked teeth progressed to fracture in 2,601 patients. Therefore, characteristics that may have predicted both crack progression and fracture were instead preemptively treated before the crack progression led to a fracture.

Limitations of this study include that neither patients nor subject teeth were randomly selected and therefore may not represent the full spectrum of individuals with cracked posterior teeth. While this is not ideal, it likely led to the high retention rate observed, as practices were able to select patients who were most likely to be retained. Another limitation is that some of the data collected are subjective and amenable to different interpretations, even though all study personnel underwent training before participating.

The study also includes several strengths, including a high number of patients drawn from a large number of practices demonstrating geographic and practice setting diversity, evaluated longitudinally, with a high rate of recall.

Conclusion:

A cohort of 2,601 patients from 199 practices with at least one vital cracked tooth was followed for three years to ascertain the development of tooth fracture and crack progression. Overall, fractures and crack progression were rare, as only 78 (3%) developed a fracture, and 232 (12% of 1,889 teeth not treated before the Y1 examination) had some type of crack progression. Characteristics associated with tooth fracture included location in the maxillary arch, a wear facet through enamel, cracks being detectable by an explorer at baseline, and cracks that ran in a horizontal direction, or which were on the facial surface. Characteristics associated with crack progression included male gender and teeth with multiple cracks at baseline. Teeth with a crack on the facial surface at baseline were less likely to demonstrate crack progression. There was no overlap between characteristics that significantly predicted tooth fracture as compared to characteristics that significantly predicted crack progression.

Table 2.

Tooth-level characteristics of subjects with a cracked tooth at baseline according to whether fractures developed or whether there was any crack progression1 during 3 years of follow-up (FU).

| Baseline tooth-level characteristics | All patients with any FU visit (N = 2,601) | Patients who developed a tooth fracture (N = 78) | Patients who were not treated before Y1 exam (N = 1,889) | Crack progressed (N = 232) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | N | Row %3 | N | N | Row %3 | |

|

| ||||||

| Molar | 2,116 | 67 | 3% | 1,509 | 170 | 11% |

| Premolar | 485 | 11 | 2% | 380 | 45 | 12% |

| cluster adjusted p 4 | P = 0.2 | P = 0.9 | ||||

| Maxillary | 1,078 | 40 | 4% | 778 | 87 | 11% |

| Mandibular | 1,523 | 38 | 2% | 1,111 | 128 | 12% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.09 | P=0.9 | ||||

| 2 or more external cracks | 1,669 | 59 | 4% | 1,210 | 153 | 13% |

| 1 external crack | 932 | 19 | 2% | 679 | 62 | 9% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.01 | P = 0.9 | ||||

| Wear facet thru enamel | 615 | 32 | 5% | 436 | 50 | 11% |

| No wear facet thru enamel | 1,986 | 46 | 2% | 1,453 | 165 | 11% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.002 | P = 0.7 | ||||

| Exposed roots | 587 | 21 | 4% | 451 | 59 | 13% |

| No exposed roots | 2,014 | 57 | 3% | 1,438 | 156 | 11% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.3 | P = 0.6 | ||||

| Caries present | 260 | 8 | 3% | 56 | 5 | 9% |

| No caries present | 2,341 | 70 | 3% | 1,033 | 210 | 11% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.9 | P = 0.8 | ||||

| NCCL5 present | 227 | 14 | 6% | 184 | 19 | 10% |

| No NCCL present | 2,374 | 64 | 3% | 1,705 | 196 | 12% |

| cluster adjusted p | P = 0.04 | P = 0.4 | ||||

Crack progression: Increases in number or cracks or number of surfaces involved in the crack.

Column Ns not summing to column total N above due to missing data.

Percent with column heading (increased number of fractures or development of fractures) within the level of tooth characteristic:

Significance of differences in proportions with column heading adjusted only for clustering of patients within practitioner using GEE.

NCCL: Non-carious cervical lesion.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants U19-DE-28717 and U19-DE-22516. Opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as necessarily representing the views of the respective organizations or the National Institutes of Health. The informed consent of all human subjects who participated in this investigation was obtained after the nature of the procedures had been explained fully. The manuscript co-authors report having no conflicts of interest. An Internet site devoted to details about the nation’s network is located at http://NationalDentalPBRN.org. We are very grateful to the network’s Regional Node Coordinators and other network staff (Midwest Region: Tracy Shea, RDH, BSDH; Western Region: Stephanie Hodge, MA; Northeast Region: Christine O’Brien, RDH; South Atlantic Region: Hanna Knopf, BA, and Deborah McEdward, RDH, BS, CCRP; South Central Region: Shermetria Massengale, MPH, CHES, and Ellen Sowell, BA; Southwest Region: Stephanie Reyes, BA, Meredith Buchberg, MPH, and Colleen Dolan, MPH; network program manager (Andrea Mathews, BS, RDH) and program coordinator (Terri Jones)), along with network practitioners and their dedicated staff who conducted the study.

Footnotes

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

The National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group comprises practitioners, faculty, and staff investigators who contributed to this network activity. A list of these persons are at http://www.nationaldentalpbrn.org/collaborative-group.php

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Thomas J. Hilton, School of Dentistry Oregon Health & Science University 2730 S.W. Moody Ave. Portland, OR 97201-5042.

Ellen Funkhouser, School of Medicine, University of Alabama, Birmingham, 1720 2nd Avenue South, Birmingham, AL 35294-0007.

Jack L. Ferracane, Department of Restorative Dentistry, School of Dentistry Oregon Health & Science University 2730 S.W. Moody Ave. Portland, OR 97201-5042.

Gregg H. Gilbert, Department of Clinical and Community Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Valeria V. Gordan, Department of Restorative Dental Sciences, University of Florida, 1600 SW Archer Rd, Gainesville, FL 32610.

Dorota T. Kopycka-Kedzierawski, Eastman Institute for Oral Health, 625 Elmwood Ave Box 683, Rochester, NY 14620.

Cyril Meyerowitz, Eastman Institute for Oral Health, University of Rochester, 601 Elmwood Avenue, Box 686, Rochester, NY 14642.

Rahma Mungia, Department of Periodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Vanessa Burton, HealthPartners 5901, John Martin Dr. Brooklyn Center, MN 55430.

References:

- 1.Hilton TJ, Ferracane JL, Madden T, Barnes C. Cracked Teeth: A Practice-based Prevalence Survey. J Dent Res 2007; 86: abst 2044. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bader JD, Shugars DA, Roberson TM; Using crowns to prevent tooth fracture. CommunityDent Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24; 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernardini F, Tuniz C, Coppa A, Mancini L, Dreossi D, et al. (2012) Beeswax as Dental Filling on a Neolithic Human Tooth. PLoS ONE 7(9): e44904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lubisich E, Hilton T, Ferracane J. Cracked teeth: a review of the literature. J Esthet Restor Dent 2010; 22:158–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron CE Cracked Tooth Syndrome. J Am Dent Assoc 1964; 68, 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chong BS Bilateral cracked teeth: a case report. Int Endod J 1989; 22(4), 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas GA The diagnosis and treatment of the cracked tooth syndrome. Aust Prosthodont J 1989;3:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geurtsen W. The cracked-tooth syndrome: clinical features and case reports. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1992;12(5), 395–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turp JC, Gobetti JP The Cracked Tooth Syndrome: an elusive diagnosis. J Am Dent Assoc 1996;127:1502–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homewood CI Cracked tooth syndrome-Incidence, clinical findings, and treatment. Aust Dent J 1998;43(4), 217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis R, Overton JD Efficacy of bonded and nonbonded amalgam in the treatment of teeth with incomplete fractures. J Am Dent Assoc 1999;130(4), 571–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratcliff S, Becker IM, Quinn L. Type and incidence of cracks in posterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 2001;86:168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch CD, McConnell RJ The Cracked Tooth Syndrome. J Can Dent Assoc 2002;68(8), 470–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffin JD Jr. Efficient, conservative treatment of symptomatic cracked teeth. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2006;27(2), 93–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seo D, Yi Y, Shin S, Parkl J. Analysis of factors associated with cracked teeth. J Endod 2012;38:288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ailor JE Managing incomplete tooth fractures, J Am Dent Assoc 2000; 131:1168–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright HM, Loushine RJ, Weller RN, Kimbrough WF, Waller J, Pashley DH Identification of resected root-end dentinal cracks: a comparative study of transillumination and dyes, J Endod 2004;30(10):712–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark DJ, Sheets CG, Paquette JM, Definitive diagnosis of early enamel and dentin cracks based on microscopic evaluation. J. Esthet Restor Dent 2003;15, SI 7-SI 17(Special Issue). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Culjat MO, Singh RS, Brown ER, Neurgaonkar RR, Yoon DC, White SN Ultrasound crack detection in a simulated human tooth. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2005; 34(2), 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imai K, Shimada Y, Sadr A, Sumi Y, Tagami J. Noninvasive cross-sectional visualization of enamel cracks by optical coherence tomography in vitro. J Endod 2012; 38:1269–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jun M, Ku H, Kim E, Kim H, Kwon HH, Kim B. Detection and Analysis of Enamel Cracks by Quantitative Light-induced Fluorescence Technology. J Endod 2016; 42:500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheets C, Wu J, Rashad S, Phelan M, Earthman J. In vivo study of the effectiveness of quantitative percussion diagnostics as an indicator of the level of the structural pathology of teeth, J Prosthet Dent 2016;116:191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheets C, Wu J, Rashad S, Phelan M, Earthman J. In vivo study of the effectiveness of quantitative percussion diagnostics as an indicator of the level of the structural pathology of teeth after restoration, J Prosthet Dent 2017;117:218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheets C, Wu J, Earthman J. Quantitative percussion diagnostics as an indicator of the level of the structural pathology of teeth: Retrospective follow-up investigation of high-risk sites that remained pathological after restorative treatment. J Prosthet Dent 2018; 119:928–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bajaj D, Sundaram N, Nazari A, Arola A. Age, dehydration and fatigue crack growth indent in. Biomaterials 2006; 27:2507–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roh B, Lee Y. Analysis of 154 cases of teeth with cracks. Dental Traumatology 2006;22:118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian Y, Zhou X, Yang J. Correlation between cuspal inclination and tooth cracked syndrome: a three-dimensional reconstruction measurement and finite element analysis Dent Traumatol. 2013. 29(3):226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bader JD, Shugars DA, Martin JA. Risk indicators for posterior tooth fracture. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;135:883–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavone BW. Bruxism and its effect on the natural teeth. J Prosthet Dent 1985;53:692–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abou-Rass M. Crack lines: the precursors of tooth fractures—their diagnosis and treatment. Quintessence Int 1983; 14:437–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maheu-Robert LF, Andrian E, Grenier D. Overview of complications secondary to tongue and lip piercings. J Can Dent Assoc 2007;73:327–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilton TJ, Funkhouser E, Ferracane JL, Gilbert GH, Baltuck C, Benjamin P, Louis D, Mungia R, Meyerowitz C, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Correlation between symptoms and external cracked tooth characteristics: findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc 2017; 148:246–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hilton T, Funkhouser E, Ferracane J, Gordan V, Huff K, Barna J, Mungia R, Marker T, Gilbert GH, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Associates of types of pain with crack-level, tooth-level, and patient-level characteristics in posterior teeth with visible cracks: Findings from the National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. J Dent 2018;70:6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilton T, Funkhouser E, Ferracane J, Schultz-Robins M, Gordan V, Bramblett B, Snead R, Manning W, Remakel J, National Dental Practice-Based Research Network Collaborative Group. Recommended treatment of cracked teeth: Results from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Prosthet Dent 2020; 123:71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hilton TJ, Funkhouser E, Ferracane JL, Gilbert GH, Gordan VV, Bennet S, Bone J, Richardson PA, Malmstrom H, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Symptom changes and crack progression in untreated cracked teeth: One-year findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Dent 2020; 93:103269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferracane JL, Funkhouser E, Hilton TJ, Gordan VV, Graves CL, Giese KA, Shea W, Pihlstrom D, Gilbert GH; National Dental Practice-Based Research Network Collaborative Group. Observable characteristics coincident with internal cracks in teeth: Findings from The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc 2018; 149:885–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Korelitz JJ, et al. Purpose, structure, and function of the United States National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Dent 2013; 41(11):1051–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krell K, Rivera E. A six-year evaluation of cracked teeth diagnosed with reversible pulpitis: treatment and prognosis. J Endod 2007; 33:1405–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opdam N, Roeters J, Loomans B,. Bronkhorst E. Seven-year Clinical Evaluation of Painful Cracked Teeth Restored with a Direct Composite Restoration. J Endod 2008;34:808 – 811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan L, Chen N, Poon C, Wong H. Survival of root filled cracked teeth in a tertiary institution. 2-yr survival of Endo tx cracked teeth. International Endodontic Journal, 2006; 39: 886–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sim I, Toh-Seong L, Chen N. Decision Making for Retention of Endodontically Treated Posterior Cracked Teeth: A 5-year Follow-up Study. J Endod 2016; 42:225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krell K, Caplan D. 12-month Success of Cracked Teeth Treated with Orthograde Root Canal Treatment. J Endod 2018; 44:543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brynjulfsen A, Fristad I, Grevstad T, Hals-Kvinnsland I. Incompletely fractured teeth associated with diffuse longstanding orofacial pain: diagnosis and treatment outcome. Int Endod J 2002; 35:461–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bader JD, Martin JA, Shugars DA. Incidence rates for complete cusp fracture. CommunityDent Oral Epidemiol 2001; 29:346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eakle WS, Maxwell EH, Braly BV. Fractures of posterior teeth in adults. J Am Dent Assoc1986;112:215–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macho G. Variation in enamel thickness and cusp area within human maxillary molars and its bearing on scaling techniques used for studies of enamel thickness between species. Arch Oral Biol. 1994; 9:7983–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dheyriat A, Frutoso J, Lissac M. The determination of the intensity of premolar and molar maximal forces during isometric contraction of the masticatory muscles due to forced mandibular closure. Bull Group Int Rech Sci Stomatol Odontol 1996; 39:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banerji S, Mehta S, Millar B. Cracked tooth syndrome. Part 1: aetiology and diagnosis. British Dent J 2010; 208:459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]