Key Points

Question

Does the presence of acute infarct on imaging attributed to the index event (index imaging) modify the association of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with subsequent ischemic stroke risk?

Findings

In this post hoc analysis of the Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke trial, DAPT was associated with decreased risk of recurrent stroke in patients with an acute infarct on index imaging. There was no association of DAPT with the risk of recurrent stroke in patients without an acute infarct on index imaging.

Meaning

Further prospective work is needed to validate these findings before targeting specific patient populations for acute DAPT.

This post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial investigates whether the association of clopidogrel-aspirin treatment with stroke recurrence in patients with minor stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack is modified by the presence of infarct on imaging attributed to the index event.

Abstract

Importance

In the Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke (POINT) trial, acute treatment with clopidogrel-aspirin was associated with significantly reduced risk of recurrent stroke. There may be specific patient groups who are more likely to benefit from this treatment.

Objective

To investigate whether the association of clopidogrel-aspirin with stroke recurrence in patients with minor stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack (TIA) is modified by the presence of infarct on imaging attributed to the index event (index imaging) among patients enrolled in the POINT Trial.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In the POINT randomized clinical trial, patients with high-risk TIA and minor ischemic stroke were enrolled at 269 sites in 10 countries in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand from May 28, 2010, to December 19, 2017. In this post hoc analysis, patients were divided into 2 groups according to whether they had an acute infarct on index imaging. All POINT trial participants with information available on the presence or absence of acute infarct on index imaging were eligible for this study. Univariable Cox regression models evaluated associations between the presence of an infarct on index imaging and subsequent ischemic stroke and evaluated whether the presence of infarct on index imaging modified the association of clopidogrel-aspirin with subsequent ischemic stroke risk. Data were analyzed from July 2020 to May 2021.

Exposures

Presence or absence of acute infarct on index imaging.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome is whether the presence of infarct on index imaging modified the association of clopidogrel-aspirin with subsequent ischemic stroke risk.

Results

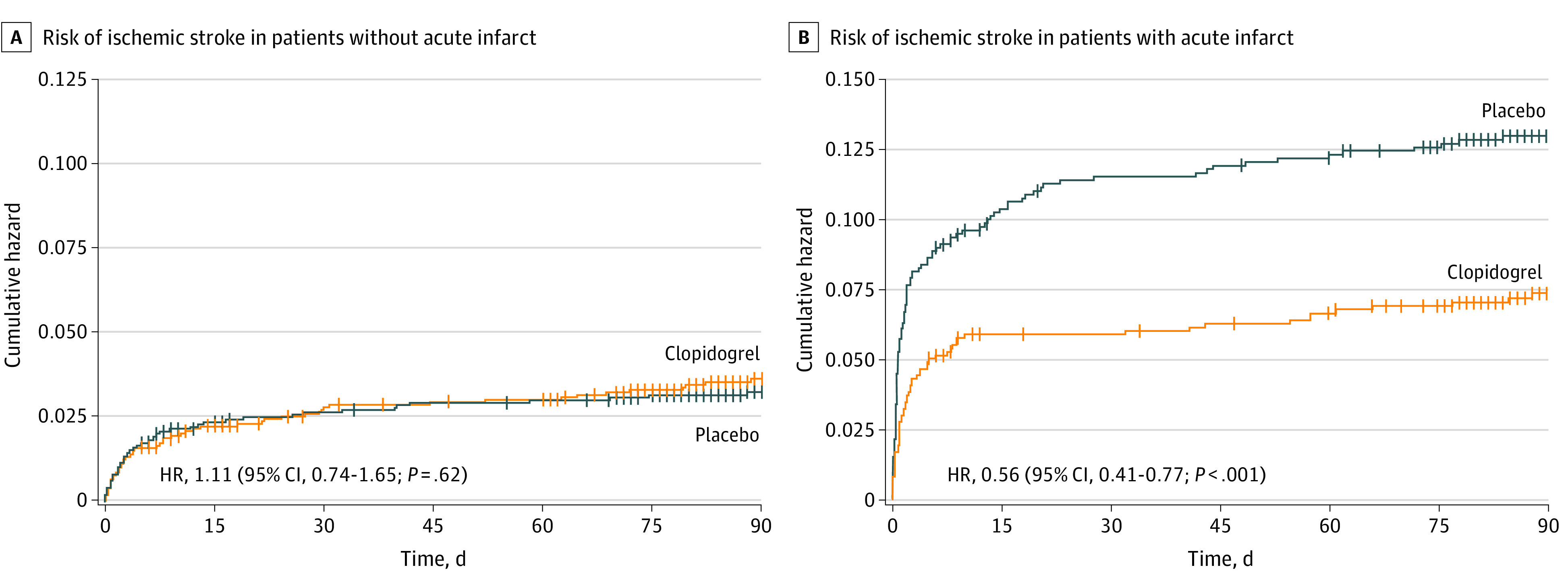

Of the 4881 patients enrolled in POINT, 4876 (99.9%) met the inclusion criteria (mean [SD] age, 65 [13] years; 2685 men [55.0%]). A total of 1793 patients (36.8%) had an acute infarct on index imaging. Infarct on index imaging was associated with ischemic stroke during follow-up (hazard ratio [HR], 3.68; 95% CI, 2.73-4.95; P < .001). Clopidogrel-aspirin vs aspirin alone was associated with decreased ischemic stroke risk in patients with an infarct on index imaging (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.41-0.77; P < .001) compared with those without an infarct on index imaging (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.74-1.65; P = .62), with a significant interaction association (P for interaction = .008).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, the presence of an acute infarct on index imaging was associated with increased risk of recurrent stroke and a more pronounced benefit from clopidogrel-aspirin. Future work should focus on validating these findings before targeting specific patient populations for acute clopidogrel-aspirin treatment.

Introduction

Patients with transient ischemic attack and minor stroke (TIAMS) are at increased short-term risk of stroke.1,2 Short-term treatment of patients with high-risk TIA (ABCD2 [age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of TIA, and presence of diabetes] score ≥4) and minor ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score ≤3) with aspirin plus clopidogrel (clopidogrel-aspirin) within 12 to 24 hours of symptom onset has been shown to substantially reduce subsequent stroke risk compared with aspirin monotherapy.3,4 Current American Heart Association and American Stroke Association guidelines recommend treatment with clopidogrel-aspirin for eligible patients with TIAMS.5

Because the use of dual antiplatelet therapy in TIAMS is associated with increased risk of bleeding complications compared with monotherapy,4,6,7,8 identifying patients with TIAMS who are most likely to benefit from this treatment is important.9 The presence of infarction on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) diffusion-weighted imaging has previously been associated with increased ischemic stroke risk among patients with TIAMS.1,10,11,12,13 In the imaging substudy of the Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events (CHANCE) trial, the presence of infarct on diffusion-weighted imaging was associated with increased risk of subsequent ischemic stroke, and compared with aspirin monotherapy, treatment with clopidogrel-aspirin was most beneficial among participants with multiple acute infarcts.9 However, only 21% of CHANCE trial participants were included in the imaging substudy, thus limiting the generalizability of those findings.9 We therefore sought to determine whether the association of clopidogrel-aspirin with reduced recurrent ischemic stroke in patients with TIAMS was modified by the presence of an acute infarct attributed to the index event among patients enrolled in the Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke (POINT) randomized clinical trial.

Methods

This study was waived by the institutional review board at NYU Langone Medical Center because it used publicly available, deidentified data, which are available upon request to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; thus, informed consent was not needed, in accordance with 45 CFR §46. This is a post hoc analysis of the POINT randomized clinical trial, which enrolled patients with minor stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score ≤3) and high-risk TIA (ABCD2 score ≥4) presenting within 12 hours from last known normal time randomized to clopidogrel-aspirin vs aspirin monotherapy.4,14 For the purpose of the current study, we excluded POINT participants for whom information on the presence or absence of acute infarct on imaging attributed to the index event was unavailable. Race and ethnicity were collected as part of demographic data for the POINT trial and were analyzed to ensure no baseline imbalance between the 2 groups.

Outcomes

Our primary study variable was the presence of an acute infarct on any imaging study attributed to the index event (index imaging). This was adjudicated by sites and was reported on case report form 20 within 12 days of randomization. Because imaging to exclude hemorrhage was required before enrollment, some portion of index imaging was completed within 12 hours of when the patients was last known to be well. Our primary study outcome was incident ischemic stroke, defined as a new focal neurological deficit with clinical or imaging evidence of infarction, or rapid worsening of an existing focal neurological deficit judged to be attributable to a new infarction. We also assessed the safety outcome of incident major hemorrhage, which was defined as one that results in symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, intraocular bleeding causing loss of vision, need for transfusion of 2 or more units of packed red blood cells or equivalent amount of whole blood, need for hospitalization or prolongation of an existing hospitalization, or death.15,16 All outcome events were adjudicated by an independent adjudication committee of neurologists, cardiologists, and internists. Further details on outcomes have been previously published.14

Statistical Analysis

We report descriptive statistics using means (SDs) for normally distributed continuous variables and medians (IQRs) for nonnormally distributed continuous variables. Categorical variables are reported using percentage and count. We used 2-sided t tests for continuous variable and 2-sided χ2 tests for categorical variable comparisons. We fit Cox proportional hazards models to the outcome of ischemic stroke and reported unadjusted hazards ratios (HRs) given data were acquired from a randomized trial. We used the Schoenfeld residual to confirm that the proportional hazards assumption of the Cox models was met and used variables as time-dependent when appropriate. We performed interaction analyses to determine whether the association of clopidogrel-aspirin vs aspirin alone with ischemic stroke risk and major hemorrhage was modified by the presence or absence of infarct on index imaging. We performed sensitivity analyses to determine the same interaction terms in patients with a diagnosis of either a TIA or minor ischemic stroke at the time of trial randomization by site investigators; this diagnosis may have been made before complete index imaging ascertainment. All analyses were conducted using in SPSS statistical software version 25.0 (IBM), and P < .05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed from July 2020 to May 2021.

Results

Of 4881 patients randomized in the POINT trial, 4876 (99.9%) met our study inclusion criteria. The mean (SD) age was 65 (13) years, and 2685 (55.0%) were men; 1793 (36.8%) had an acute infarct on an imaging study attributed to the index event (index imaging). A total of 266 patients (5.5%) had an ischemic stroke within 90 days.

Table 1 summarizes the univariable analyses. In brief, patients with an acute infarct on index imaging were more likely to be men (1107 men [61.7%] vs 1578 men [51.2%]; χ21 = 51.06; P < .001), less likely to have hypertension (1206 patients [67.6%] vs 2165 patients [70.5%]; χ21 = 4.28; P = .04), less likely to be taking a statin (632 patients [35.2%] vs 1257 patients [40.8%]; χ21 = 14.71; P < .001), and more likely to have undergone a brain MRI (1270 patients [70.8%] vs 1478 patients [47.9%]; χ21 = 241.52; P < .001). In addition, they had higher mean (SD) baseline systolic blood pressure (163 [29] vs 161 [26] mm Hg; difference, 2.00 mm Hg; 95% CI, 0.42-3.58 mm Hg; P = .004) and baseline diastolic blood pressure (90 [18] vs 87 [16] mm Hg; difference, 3.00 mm Hg; 95% CI, 2.02-3.98 mm Hg; P < .001). Of the 2748 patients who underwent an MRI, 1541 (56.1%) were completed within 12 hours of the time when the patients were last known to be well; 1270 of these 2748 patients (46.2%) had an infarct on MRI.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics and Outcome Between Patients With vs Without Infarct on Imaging Attributable to the Index Event.

| Characteristic | Infarct on imaging, participants, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 1793) | No (n = 3083) | ||

| Demographic | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 64.2 (12.7) | 64.8 (13.4) | .11 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1107 (61.7) | 1578 (51.2) | <.001 |

| Female | 686 (38.3) | 1505 (48.8) | |

| Race, participants, No./total No. (%)a | |||

| Asian | 64/1723 (3.7) | 80/2975 (2.7) | .33 |

| Black | 341/1723 (19.8) | 625/2975 (21.0) | |

| White | 1305/1723 (75.7) | 2245/2975 (75.5) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, participants, No./total No. (%) | 111/1698 (6.5) | 276/2945 (9.4) | .001 |

| Comorbidities, participants, No./total No. (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 1206/1783 (67.6) | 2165/3072 (70.5) | .04 |

| Diabetes | 470/1788 (26.3) | 869/3079 (28.2) | .15 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 170/1790 (9.5) | 327/3074 (10.6) | .21 |

| Active smoking | 442/1791 (24.7) | 562/3081 (18.2) | <.001 |

| Medications at randomization | |||

| Aspirin | 1005 (56.1) | 1808 (58.6) | .08 |

| Statin | 632 (35.2) | 1257/3081 (40.8) | <.001 |

| Clinical variables | |||

| Blood pressure, mm Hg, mean (SD) | |||

| Systolic | 163 (29) | 161 (27) | .004 |

| Diastolic | 90 (18) | 87 (16) | <.001 |

| Minor stroke diagnosed at randomization | 1430 (79.8) | 1339 (43.4) | <.001 |

| Transient ischemic attack diagnosed at randomization | 363 (20.2) | 1744 (56.6) | <.001 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging performed | 1270 (70.8) | 1478 (47.9) | <.001 |

| Treatment randomization to clopidogrel | 886 (49.4) | 1545 (50.1) | .64 |

| Study outcomes | |||

| Stroke | |||

| Ischemic | 169 (9.4) | 97 (3.1) | <.001 |

| Hemorrhagic | 4 (0.2) | 4 (0.1) | .48 |

| Major hemorrhage | 15 (0.8) | 18 (0.6) | .30 |

Patients with other or more than 1 race were excluded from the total.

Association Between Infarct on Index Imaging and Ischemic Stroke and Efficacy and Safety of Clopidogrel-Aspirin in Patients With vs Without Infarct on Index Imaging

The presence of infarct on index imaging was associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke at 90 days (HR, 3.68; 95% CI, 2.73-4.95; P < .001). Clopidogrel-aspirin vs aspirin alone was associated with reduced ischemic stroke risk at 90 days in patients with infarct on index imaging (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.41-0.77; P < .001) but not in those without infarct on index imaging (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.74-1.65; P = .62) with a significant interaction association (P for interaction = .008) (Table 2 and Figure). Among both patients who did and did not undergo MRI, clopidogrel-aspirin vs aspirin alone was significantly associated with reduced ischemic stroke risk among patients with infarct on imaging at 90 days but not among patients without infarct (Table 2). The association of clopidogrel-aspirin vs aspirin alone with major hemorrhage was not different in patients with infarct on index imaging (HR, 2.05; 95% CI, 0.70-5.99; P = .19) vs those without infarct on index imaging (HR, 2.59; 95% CI, 0.92-7.27; P = .07) (P for interaction = .76).

Table 2. Association of Aspirin Monotherapy vs Clopidogrel-Aspirin With Ischemic Stroke in Patients With vs Without Infarct Imaging Attributable to the Index Event.

| Variable | Aspirin alone vs clopidogrel-aspirin for ischemic stroke | HR for ischemic stroke | P value for interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No./total No. (%) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| All patients | |||||

| Infarct on imaging | 108/907 (11.9) vs 61/886 (6.9) | <.001 | 0.56 (0.41-0.77) | <.001 | .008 |

| No infarct on imaging | 46/1538 (3.0) vs 51/1545 (3.3) | .62 | 1.11 (0.74-1.65) | .62 | |

| MRI performed | |||||

| Infarct on imaging | 66/634 (10.4) vs 38/636 (6.0) | .004 | 0.55 (0.37-0.82) | .004 | .01 |

| No infarct on imaging | 18/710 (2.5) vs 27/768 (3.5) | .29 | 1.39 (0.77-2.52) | .28 | |

| MRI not performed | |||||

| Infarct on imaging | 42/273 (15.4) vs 23/250 (9.2) | .03 | 0.59 (0.36-0.99) | .04 | .25 |

| No infarct on imaging | 28/828 (3.3) vs 24/777 (3.1) | .74 | 0.91 (0.53-1.58) | .75 | |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure. Risk of Ischemic Stroke in Patients With and Without Acute Infarct on Imaging.

Ischemic stroke risk in patients without (A) and with (B) acute infarct on an imaging study attributed to the index event. Vertical lines denote data censoring. HR indicates hazard ratio.

Sensitivity Analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis to explore whether the association of clopidogrel-aspirin vs aspirin alone in those with vs without infarct on index imaging differed by the diagnosis assigned at randomization (minor ischemic stroke vs TIA). Among participants whose index event was diagnosed as a TIA at randomization, the association of clopidogrel-aspirin vs aspirin alone with reduced ischemic stroke risk was not significantly different in patients with acute infarct on index imaging (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.32-1.34; P = .25) vs those without acute infarct on index imaging (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.53-1.48; P = .65) (P for interaction = .49) (Table 3). In contrast, among patients with an initial diagnosis of minor ischemic stroke at the time of randomization, there was a significant association of clopidogrel-aspirin vs aspirin alone with reduced ischemic stroke risk in patients with acute infarct on index imaging (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.38-0.77; P = .001) but not in those without acute infarct on index imaging (HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 0.81-2.98; P = .18) (P for interaction = .005) (Table 3).

Table 3. Association of Aspirin Monotherapy vs Clopidogrel-Aspirin With Ischemic Stroke in Patients With vs Without Infarct on Imaging Attributable to the Index Event Divided by Diagnosis at Randomization.

| Variable | Aspirin alone vs clopidogrel-aspirin for ischemic stroke | HR for ischemic stroke | P value for interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No./total No. (%) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Transient ischemic attack at randomization | |||||

| Infarct on imaging | 19/184 (10.3) vs 12/179 (6.7) | .22 | 0.65 (0.32-1.34) | .25 | .49 |

| No infarct on imaging | 31/867 (3.6) vs 28/877 (3.2) | .66 | 0.89 (0.53-1.48) | .65 | |

| Minor stroke at randomization | |||||

| Infarct on imaging | 89/723 (12.3) vs 49/707 (6.9) | .001 | 0.54 (0.38-0.77) | .001 | .005 |

| No infarct on imaging | 15/671 (2.2) vs 23/668 (3.4) | .18 | 1.56 (0.81-2.98) | .18 | |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of the POINT randomized clinical trial, we found that patients with TIAMS who present with infarct on index imaging had increased risk of recurrent stroke and that acute clopidogrel-aspirin treatment was associated with a significant decrease in this risk. The presence of an acute infarct on imaging associated with the index event modified the association of acute clopidogrel-aspirin with reducing recurrent stroke. These findings are in line with prior studies,10,17,18,19 including a substudy of the CHANCE trial, in which patients with acute infarct on MRI were at increased risk of subsequent stroke and those with multiple infarcts on imaging had the most pronounced clinical benefit from clopidogrel-aspirin.9

There are several potential reasons for our finding that the association of clopidogrel-aspirin with patients enrolled in POINT was present only among those with vs without infarct on imaging attributed to the index event. First, it is possible that patients who did not have an infarct on imaging, particularly if MRI was performed, had a noncerebrovascular cause for their deficits (stroke mimic). These false-positive patients would be expected to have a much lower 90-day ischemic stroke risk than patients with a true ischemic event and, thus, would be unlikely to benefit from clopidogrel-aspirin. It is also possible that subjects without an infarct on imaging were more likely to have a small-vessel cause for their ischemic event, which has a lower short-term risk of recurrence than other stroke subtypes,20 or that, because patients with imaging-negative events are at lower risk of stroke recurrence,21,22 we were simply underpowered to detect a smaller benefit for clopidogrel-aspirin in this patient population. Alternatively, because subjects with an acute infarct on index imaging were more likely to have undergone brain MRI in our study, it is possible that patients selected for advanced neuroimaging were thought to be at higher risk for stroke by the treating physician than subjects for whom only a head computed tomography image was obtained. Given the known discrepancies between physician judgment and advanced imaging findings after TIAMS,21 treating physician imaging selection may have led to infarct underdetection in our study.

There are potential practical implications to our findings that require additional confirmation. On the basis of our results, the use of MRI in the acute workup of patients with TIAMS may be preferred to identify those at highest risk of recurrent stroke. At present, the use of MRI for TIAMS evaluation is highly variable, and physicians’ ability to estimate which patients will have infarct on imaging is poor.23,24 Whether MRI should be used to target a subgroup of patients with TIAMS who are most likely to benefit from clopidogrel-aspirin requires further study. The use of this MRI to detect infarcts may be particularly relevant in patients at increased risk of hemorrhagic complications,25 although we did not find higher rates of hemorrhage among patients treated with clopidogrel-aspirin in this substudy or among patients with vascular events who would not have met the original POINT study inclusion criteria on the basis of their presenting symptoms (eg, isolated numbness, isolated visual changes, or isolated dizziness or vertigo) but are at increased stroke risk.26

Interestingly, we found that the presence of an acute infarct on imaging associated with the index event modified the association of acute clopidogrel-aspirin with recurrent stroke in patients with an initial diagnosis of a minor stroke at the time of randomization, as opposed to those with an initial diagnosis of TIA. This finding suggests that a number of patients with persistent minor symptoms who ultimately were not found to have an acute infarct on advanced imaging likely had a noncerebrovascular cause for their symptoms (ie, stroke mimics). Differentiating between true cerebrovascular disease and other noncerebrovascular conditions among patients who present with persistent minor neurological deficits, particularly in the acute setting, can be challenging.27 Our sensitivity analyses, thus, further underscore the importance of imaging to improve diagnostic accuracy even among patients with persistent rather than transient symptoms.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include a large sample of data from a randomized clinical trial with centralized outcome adjudication. In addition, we included patients with acute infarct on any imaging modality, including a proportion with CT only, which increases the generalizability of our findings. Our study also has several limitations. First, it is a post hoc analysis and, therefore, in the strictest sense, our results are hypothesis generating.28 Second, the infarct on imaging attributed to the index event variable was adjudicated by local sites without core imaging laboratory verification. Third, we do not have data on infarct pattern or multiplicity, location, presumed stroke mechanism (eg, small-vessel disease), or other imaging variables such as intracranial stenosis, which likely are associated with the stroke recurrence rates.17,29 Although in The Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Treated With Ticagrelor and ASA for Prevention of Stroke and Death (THALES) trial, there may be additional stroke risk reduction among patients with large-vessel atherosclerotic disease treated with aspirin-ticagrelor,30 in a post hoc analysis of POINT, the association of clopidogrel-aspirin with patients with carotid stenosis greater than 50% vs aspirin alone was similar.31 We did not evaluate for the effects of atherosclerotic mechanism in this study. We also cannot fully exclude the possibility that MRI was selectively performed for subjects perceived as being at higher stroke risk, although the fact that infarct on imaging was not found in more than one-half of patients for whom MRI was performed is reassuring.

Conclusions

In this post hoc analysis of the POINT randomized clinical trial, patients with an acute infarct on imaging attributed to the index event faced an increased risk of ischemic stroke, which was reduced by acute clopidogrel-aspirin treatment. Future work is needed to validate these findings and to evaluate the role of MRI in acute TIAMS treatment decision-making.

References

- 1.Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, et al. ; TIAregistry.org Investigators . One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1533-1542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lioutas VA, Ivan CS, Himali JJ, et al. Incidence of transient ischemic attack and association with long-term risk of stroke. JAMA. 2021;325(4):373-381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.25071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. ; CHANCE Investigators . Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):11-19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. ; Clinical Research Collaboration, Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials Network, and the POINT Investigators . Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):215-225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council . 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao Q, Tampi M, O’Donnell M, Foroutan F, Siemieniuk RA, Guyatt G. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone for acute minor ischaemic stroke or high risk transient ischaemic attack: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;363:k5108. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k5108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H, et al. ; THALES Investigators . Ticagrelor and aspirin or aspirin alone in acute ischemic stroke or TIA. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):207-217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatia K, Jain V, Aggarwal D, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2021;52(6):e217-e223. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.033033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jing J, Meng X, Zhao X, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy in transient ischemic attack and minor stroke with different infarction patterns: subgroup analysis of the CHANCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(6):711-719. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merwick A, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Addition of brain and carotid imaging to the ABCD2 score to identify patients at early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1060-1069. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70240-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ay H, Arsava EM, Johnston SC, et al. Clinical- and imaging-based prediction of stroke risk after transient ischemic attack: the CIP model. Stroke. 2009;40(1):181-186. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.521476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Addition of brain infarction to the ABCD2 score (ABCD2I): a collaborative analysis of unpublished data on 4574 patients. Stroke. 2010;41(9):1907-1913. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.578971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coutts SB, Simon JE, Eliasziw M, et al. Triaging transient ischemic attack and minor stroke patients using acute magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 2005;57(6):848-854. doi: 10.1002/ana.20497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke (POINT) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke. 2013;8(6):479-483. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulman S, Kearon C; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis . Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692-694. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. ; PRoFESS Study Group . Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(12):1238-1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yaghi S, Rostanski SK, Boehme AK, et al. Imaging parameters and recurrent cerebrovascular events in patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(5):572-578. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knoflach M, Lang W, Seyfang L, et al. ; Austrian Stroke Unit Collaborators . Predictive value of ABCD2 and ABCD3-I scores in TIA and minor stroke in the stroke unit setting. Neurology. 2016;87(9):861-869. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer L, Ferrari J, Krebs S, et al. ; Austrian Stroke Unit Collaborators . ABCD3-I score and the risk of early or 3-month stroke recurrence in tissue- and time-based definitions of TIA and minor stroke. J Neurol. 2018;265(3):530-534. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8720-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson C, Sudlow C. Comparing risks of death and recurrent vascular events between lacunar and non-lacunar infarction. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 11):2507-2517. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurford R, Li L, Lovett N, Kubiak M, Kuker W, Rothwell PM; Oxford Vascular Study . Prognostic value of “tissue-based” definitions of TIA and minor stroke: population-based study. Neurology. 2019;92(21):e2455-e2461. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Early stroke risk and ABCD2 score performance in tissue- vs time-defined TIA: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2011;77(13):1222-1228. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182309f91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coutts SB, Moreau F, Asdaghi N, et al. ; Diagnosis of Uncertain-Origin Benign Transient Neurological Symptoms (DOUBT) Study Group . Rate and prognosis of brain ischemia in patients with lower-risk transient or persistent minor neurologic events. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(12):1439-1445. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaturvedi S, Ofner S, Baye F, et al. Have clinicians adopted the use of brain MRI for patients with TIA and minor stroke? Neurology. 2017;88(3):237-244. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D, Gui L, Dong Y, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy may increase the risk of non-intracranial haemorrhage in patients with minor strokes: a subgroup analysis of the CHANCE trial. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2016;1(2):29-36. doi: 10.1136/svn-2016-000008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuna MA, Rothwell PM; Oxford Vascular Study . Diagnosis of non-consensus transient ischaemic attacks with focal, negative, and non-progressive symptoms: population-based validation by investigation and prognosis. Lancet. 2021;397(10277):902-912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31961-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khatri P, Kleindorfer DO, Devlin T, et al. ; PRISMS Investigators . Effect of alteplase vs aspirin on functional outcome for patients with acute ischemic stroke and minor nondisabling neurologic deficits: the PRISMS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(2):156-166. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srinivas TR, Ho B, Kang J, Kaplan B. Post hoc analyses: after the facts. Transplantation. 2015;99(1):17-20. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolominsky-Rabas PL, Weber M, Gefeller O, Neundoerfer B, Heuschmann PU. Epidemiology of ischemic stroke subtypes according to TOAST criteria: incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival in ischemic stroke subtypes: a population-based study. Stroke. 2001;32(12):2735-2740. doi: 10.1161/hs1201.100209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amarenco P, Denison H, Evans SR, et al. ; THALES Steering Committee and Investigators . Ticagrelor added to aspirin in acute nonsevere ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack of atherosclerotic origin. Stroke. 2020;51(12):3504-3513. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaghi S, de Havenon A, Rostanski S, et al. Carotid stenosis and recurrent ischemic stroke: a post-hoc analysis of the POINT trial. Stroke. 2021;52(7):2414-2417. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]