Key Points

Question

What are the long-term psychological outcomes among children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU)?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 31 independent studies involving 7786 children admitted to the PICU, 5.3% to 88.0% of children experienced psychological issues 3 months to 15 years later. Compared with healthy children, those admitted to the PICU had lower IQ scores at 5 years, developed more total emotional and behavioral problems, and had worse memory.

Meaning

This study found a high burden of psychological sequelae among children who were admitted to the PICU, suggesting that risk stratification and early intervention for high-risk groups are needed to minimize long-term psychological morbidities.

Abstract

Importance

The pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) exposes children to stressful experiences with potential long-term psychological repercussions. However, current understanding of post-PICU psychological outcomes is incomplete.

Objective

To systematically review and evaluate reported long-term psychological outcomes among children previously admitted to the PICU.

Data Sources

A systematic search of the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, MEDLINE (PubMed), and PsycINFO was conducted from database inception to June 2021. Search terms included phrases related to intensive care (eg, intensive care units and critical care) and terms for psychological disorders (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder, depressive disorder, conduct disorder, and neurodevelopmental disorder) limited to the pediatric population.

Study Selection

This systematic review and meta-analysis included randomized clinical trials and observational studies reporting psychological disorders among children younger than 18 years who were admitted to the PICU with follow-up for at least 3 months. Psychological disorders were defined using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition). Children were excluded if they were admitted to the PICU for primary brain conditions (eg, traumatic brain injury, meningoencephalitis, and brain tumors) or discharged to the home for palliative care.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Titles and abstracts were independently screened by 2 reviewers, with data extraction conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline. Data were pooled using a random-effects model during meta-analysis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Age-corrected IQ scores and long-term psychological outcomes measured by scales such as the Child Behavior Checklist (higher scores indicate more behavioral problems) among children admitted to the PICU.

Results

Of 9193 records identified, 31 independent studies (5 randomized clinical trials and 26 observational studies) involving 7786 children (mean age, 7.3 years [95% CI, 6.2-8.4 years]; 4267 boys [54.8%]; race and ethnicity were not reported by all studies) admitted to the PICU were included. Overall, 1 of 19 children (5.3%) to 14 of 16 children (88.0%) previously admitted to the PICU were reported to have at least 1 psychological disorder. Studies that examined posttraumatic stress disorder reported that 6 of 60 children (10.0%) to 31 of 102 children (30.4%) met the diagnostic criteria for the disorder at 3 to 6 months of follow-up. Compared with healthy children, those admitted to the PICU had lower IQ scores at 1 to 2 years of follow-up (mean, 89.40 points [95% CI, 88.33-90.47 points] vs 100.70 points [95% CI, 99.43-101.97 points]; P < .001) and 3 to 5 years of follow-up (mean, 88.54 points [95% CI, 83.92-93.16 points] vs 103.18 [95% CI, 100.36-105.99 points]; P < .001) and greater total emotional and behavioral problems at 4 years of follow-up (mean, 51.69 points [95% CI, 50.37-53.01 points] vs 46.66 points [95% CI, 45.20-48.13 points]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

This systematic review and meta-analysis found a high burden of psychological sequelae among children previously admitted to the PICU, suggesting that risk stratification and early interventions are needed for high-risk groups.

This systematic review and meta-analysis examines long-term psychological outcomes of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit.

Introduction

Mortality rates in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) have been decreasing despite increasing admissions over the past decade.1 Most children admitted to the PICU survive and experience good physical recovery.2,3 Despite these improvements, long-term psychological morbidities among children admitted to the PICU are increasing.4 There is an increasing body of evidence to suggest that PICU experiences5,6 and interventions7 are associated with negative long-term psychological outcomes. Focus on survivorship after PICU admission would benefit from including a consideration of the psychological well-being of these children.

Compared with adults, children have fewer life experiences and psychological reserves to help them adjust to adversity, which predisposes them to greater psychological vulnerabilities.8,9 Among children admitted to the PICU, younger age at PICU admission, greater severity of illness, and exposure to higher numbers of invasive procedures have been associated with greater fear and a reduced sense of control over their health.5 These factors make children more susceptible to psychological sequelae.10 Based on increasing recognition of post-PICU psychological problems, mental health was included as 1 of the 3 arms in the Post Intensive Care Syndrome in Pediatrics (PICS-p) framework alongside physical and cognitive problems.11 The PICS-p framework serves as a system to describe the recovery of children discharged from the PICU and aid the development of interventions to optimize survival among children needing critical care. Given that the PICS-p framework was only conceptualized in 2018,11 more empirical studies are needed to validate and refine it.

A wide variety of post-PICU psychological problems have been described in individual studies. These problems include posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),10,12 cognitive impairment,7 emotional and behavioral problems,13 attention deficit,7 and developmental delay.14,15 However, lack of a summary describing the epidemiologic factors associated with post-PICU psychological problems remains. To our knowledge, no systematic reviews of post-PICU psychological outcomes have been performed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition; DSM-5) classification of psychological disorders.16 Previous systematic reviews17,18 of post-PICU psychological outcomes have only focused on PTSD, anxiety, and depression and have not examined other important psychological outcomes (eg, behavioral and adjustment problems, cognitive and memory impairment, attention deficit, and developmental delay) that are included in the DSM-5. In this systematic review, we aimed to synthesize the literature describing long-term psychological problems among children admitted to the PICU using DSM-5 criteria. We also aimed to identify risk factors associated with the various psychological outcomes.

Methods

A systematic computerized search of the literature in the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, MEDLINE (PubMed), and PsycINFO was conducted by a medical research librarian (B.M.) from database inception to September 2020. An updated search was performed in June 2021 to retrieve articles published after the initial search. This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline19 (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The detailed study protocol was prospectively registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD42021231781).

A combination of controlled vocabulary and key words related to intensive or critical care (eg, intensive care units and critical care) combined with a number of psychological disorders (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder, depressive disorder, conduct disorder, and neurodevelopmental disorder) listed in the DSM-516 were searched (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Search results were limited to the pediatric population (aged <18 years) and the English language.

Titles and abstracts retrieved from the search and reference lists of selected articles were screened independently by 2 of 4 reviewers (M.S.M.K., P.F.P., K.Y.C.H., or R.W.L.N.) using Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation). Disagreements were resolved by consensus between reviewers. Full-text articles were retrieved if the abstract provided insufficient information to establish eligibility or if the article passed the first eligibility screening.

Studies were included if they (1) were conducted among pediatric patients younger than 18 years with previous hospitalization in the PICU, (2) had follow-up duration of at least 3 months, (3) included a sample of at least 10 patients, and (4) performed a quantitative analysis. Exclusion criteria were (1) non-PICU (eg, neonatal intensive care unit or adult intensive care unit) admissions; (2) pediatric patients admitted for primary brain conditions, such as brain injuries, meningoencephalitis, or brain tumors; (3) pediatric patients discharged to the home for palliative care; and (4) nonprimary literature (eg, case reports, case series, commentaries, conference articles, meta-analyses, and review articles).

Data were extracted by 2 authors (M.S.M.K. and K.Y.C.H.) from included studies using a prespecified and pilot tested standardized coding form. For studies with incomplete or missing data, 3 separate attempts at least 1 week apart were made to contact the corresponding authors. If multiple studies using the same patient database for a specific psychological outcome were identified, only the study with the largest sample was included in our analysis to avoid double counting of patients.20 Studies were analyzed in the following psychological outcome groups: attention deficit, anxiety, cognitive impairment, decrease in overall health, depression, developmental delay, emotional and behavioral problems, memory impairment, and PTSD.

Statistical Analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager software, version 5.4 (RevMan; Nordic Cochrane Centre), for psychological outcomes that were reported by at least 2 independent studies. To ensure comparability across scales, results from different studies were only pooled if similar measurement tools were used to assess the outcomes. Because we expected substantial heterogeneity between studies, we used a random-effects model for the analysis. Heterogeneity across studies was reported using the I2 statistic.

Risk of bias assessment was performed for all included studies at the study level using the Cochrane risk of bias tool21 for randomized clinical trials (RCTs), the Newcastle Ottawa Scale22 for cohort and case-control studies, and the adjusted Newcastle Ottawa Scale23 for cross-sectional studies (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

All data were analyzed using Review Manager software, version 5.4. The significance threshold was P < .05, and all tests were 2-sided.

Results

Study and Patient Characteristics

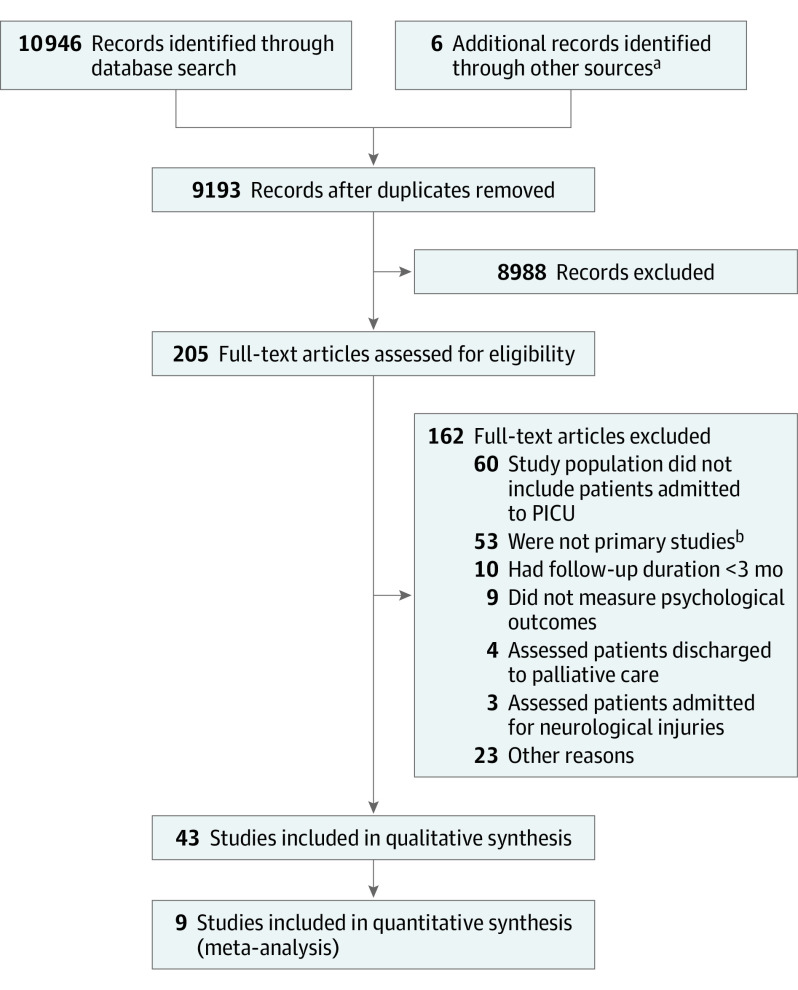

Our search strategy identified 9193 records. Of those, 205 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 43 articles5,7,10,12,13,14,15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 consisting of 31 independent studies5,7,12,13,14,15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48 involving 7786 children admitted to the PICU were included in the systematic review (Figure 1). Of the 31 independent studies, 5 were RCTs,24,25,26,27,28 13 were prospective cohort studies,5,13,14,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 10 were retrospective cohort studies,7,12,15,39,40,41,42,43,44,45 1 was a case-control study,46 and 2 were cross-sectional studies.47,48 Findings derived from the same study samples included in 6 of the independent studies5,26,28,29,34,41 (2 of which were RCTs26,28 and 4 of which were observational studies5,29,34,41) were published in multiple articles (18 total5,10,26,28,29,34,41,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59) (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram.

aReference lists of related articles were searched to identify additional records.

bIncluded case reports, case series, commentaries, conference abstracts, editorial letters, meta-analyses, news articles, non–peer reviewed articles, review articles, and study protocols.

The 31 independent studies5,7,12,13,14,15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48 comprised 20 cohorts5,7,12,13,24,25,26,27,28,31,32,33,34,35,36,43,44,46,47,48 admitted to the PICU for a variety of indications (referred to as mixed PICU cohorts [6654 total patients]), 4 cohorts15,38,40,42 admitted for cardiac surgery (584 total patients), 2 cohorts29,37 admitted for cardiac arrest (199 total patients), 2 cohorts39,41 admitted for septic shock (170 total patients), 1 cohort14 admitted for pertussis (111 total patients), 1 cohort30 admitted for severe acute asthma (50 total patients), and 1 cohort45 admitted for bronchiolitis (18 total patients). Of the 31 independent studies,5,7,12,13,14,15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48 8 studies5,7,12,26,27,30,33,46 reported a comparison group. The comparison groups comprised 1247 total participants, of whom 737 were healthy children,7,26,27,46 155 were children admitted to the general pediatric ward,5,12,30 and 355 were children who had survived a major fire.33 One study,32 in which 36 of 97 patients (37.1%) had traumatic brain injuries, was included because the results for those patients could be separated during analysis. All studies5,7,10,12,13,14,15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 were published between 1995 and 2020, with follow-up duration ranging from 3 months to 15 years.

Among 7786 total participants, the mean age was 7.3 years (95% CI, 6.2-8.4 years); 4267 participants (54.8%) were male, and 3519 (45.2%) were female. Not all studies reported race and ethnicity; studies in which data on race and ethnicity were reported are shown in the third column of eTable 4 in the Supplement. Of 11 studies7,12,24,25,27,28,31,34,43,47,50 involving mixed PICU cohorts that reported indications for PICU admission, cardiovascular7,12,25,27,28,31,34,43,47,50 (1646 of 3791 patients [37.5%; 95% CI, 21.4%-57.0%]) and respiratory12,24,25,28,31,34,43,50 (1106 of 3171 patients [30.8%; 95% CI, 19.4%-45.2%]) indications were the most common. All studies5,7,10,12,13,14,15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 were conducted in North America (Canada5,10,25,26,29,37,38,40,49,50,51 and the US14,15,24,28,29,31,35,36,42,45,48,51,53,54), Europe (Belgium,7,26,27,49,50 Finland,43 Germany,47 the Netherlands,13,26,30,33,39,41,49,50,52,55,56,57 the United Kingdom12,29,32,44,46,51), and Australia34,58,59 (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). No studies were identified from Asia, Africa, or South America.

Summary of Psychological Outcomes

Overall, 1 of 19 children (5.3%)12 to 14 of 16 children (88.0%)37 had psychological issues ranging from 3 months to 15 years after PICU admission.5,7,10,12,13,14,15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 Emotional and behavioral problems (22 total studies5,7,10,13,26,27,28,29,30,31,36,37,40,43,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55 based on 15 independent studies5,7,13,27,28,29,30,31,36,37,40,43,48,50,52) and cognitive impairment (19 total studies7,13,26,27,29,36,37,39,40,41,42,45,47,49,50,51,52,56,57 based on 13 independent studies7,13,27,29,36,37,39,40,41,42,45,47,50) were most common, followed by PTSD (11 total studies5,10,12,24,30,32,33,34,35,58,59 based on 8 independent studies5,12,24,30,32,33,34,35), anxiety (2 independent studies25,39), memory impairment (4 independent studies7,27,46,50), attention deficit (3 independent studies7,27,50), developmental delay (3 independent studies14,15,38), depression (1 independent study39), and decrease in overall health (1 independent study44) (eTable 4 in the Supplement). The Table summarizes studies reporting commonly used measurement tools to assess these outcomes.

Table. Included Studies According to Psychological Outcomes of Interest.

| Sourcea | Location | Study design | Study population | Participants, No. | Age at admission | Follow-up measure and timing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||||||

| Colville and Pierce,32 2013 | United Kingdom | Prospective cohort | Mixed PICU | 38 | Median, 11 y (IQR, 7-17 y) | CRIES at 8 mo to 1 y |

| Rennick et al,10 2004b | Canada | Retrospective cohort | Mixed PICU | 60 | Low-risk group: median, 11.5 y (IQR, 10.5-12.5 y); high-risk group: median, 11.1 y (IQR, 9.5-12.6 y) | CIES at 6 mo; CMFS at 6 mo |

| Watson et al,24 2018 | US | RCT | Mixed PICU | 1073 | Sedation protocol: median, 1.4 y (IQR, 0.3-6.8 y); usual care: median, 3.4 y (IQR, 0.8-8.9 y) |

CPSS at 6 mo |

| Le Brocque et al,34 2020c | Australia | Prospective cohort | Mixed PICU | 272 | Mean (SD), 7.67 (4.44) y | TSCYC at 12 mo |

| Boeschoten et al,30 2020 | The Netherlands | Prospective cohort | Severe asthma | 20 (vs 62 in general ward) | PICU: median, 8 y (IQR, 6-12 y); general ward: median, 5 y (IQR, 3-6 y) | CRTI at 5 mo |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Bronner et al,39 2009 | The Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | Septic shock | 50 | Median, 4.2 y (IQR, 0-17.0 y) | STAI at 6.5 y |

| Cognitive impairment | ||||||

| Verstraete et al,7 2016 | Belgium | Retrospective cohort | Mixed PICU | 449 (vs 100 in healthy control group) | Development cohort: median, 3.4 y (IQR, 2.9-4.0 y); validation cohort: median, 3.3 y (IQR, 2.7-3.8 y) | WIS at 4 y |

| Mesotten et al,27 2012 | Belgium | RCT | Mixed PICU | 456 (vs 216 in healthy control group) | Median, 5.2 y (IQR, 4.2-8.3 y) | WIS at 3 y |

| Verstraete et al,26 2019d | Belgium, Canada, and the Netherlands | RCT | Mixed PICU | 391 (vs 405 in healthy control group) | Mean (SD), 3.7 (2.5) y | WPPSI at 2 y; BRIEF at 2 y |

| Jacobs et al,50 2020d | Belgium, Canada, and the Netherlands | RCT | Mixed PICU | 684 (vs 369 in healthy control group) | Mean (SD), 7.3 (4.3) y | WPPSI at 4 y; BRIEF at 4 y |

| Meyburg et al,47 2018 | Germany | Single-center prevalence | Mixed PICU | 47 | Mean (SD), 5.1 (4.6) y | WISC or WPPSI at 17.7 mo (2.9) |

| Lequier et al,37 2008 | Canada | Prospective cohort | Cardiac arrest | 16 | Mean (SD), 53 (12) mo | WPPSI at 53 mo (12) |

| Forbess et al,42 2002 | US | Retrospective cohort | Cardiac surgery | 243 | Mean (SD), 277.3 (471.2) d | WPPSI-R at 5 y |

| Slomine et al,29 2018e | Canada, United Kingdom, and US | RCT | Cardiac arrest | 160 | Median, 2.5 y (IQR, 1.3-6.1 y) | WASI at 1 y |

| Abend et al,36 2015 | US | Prospective cohort | Mixed PICU | 20 | Median, 10.6 y (IQR, 6.7-15.4 y) | BRIEF at 2.6 y (1.2-3.8) |

| Emotional and behavioral problems | ||||||

| Verstraete et al,7 2016 | Belgium | Retrospective cohort | Mixed PICU | 449 (vs 100 in healthy control group) | Development cohort: median, 3.4 y (IQR, 2.9-4.0 y); validation cohort: median, 3.3 y (IQR, 2.7-3.8 y) | CBCL at 4 y |

| Verstraete et al,26 2019d | Belgium, Canada, and the Netherlands | RCT | Mixed PICU | 391 (vs 405 in healthy control group) | Mean (SD), 3.7 (2.5) y | CBCL at 2 y |

| Jacobs et al,50 2020d | Belgium, Canada, and the Netherlands | RCT | Mixed PICU | 684 (vs 369 in healthy control group) | Mean (SD), 7.3 (4.3) y | CBCL at 4 y |

| Buysse et al,52 2010f | The Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | Septic shock | 120 | Median, 3.10 y (IQR, 0.10-17.9 y) | CBCL at 9.8 y |

| Mesotten et al,27 2012 | Belgium | RCT | Mixed PICU | 456 (vs 216 in healthy control group) | Median, 5.2 y (IQR, 4.2-8.3 y) | CBCL at 3 y |

| Biagas et al,31 2020 | US | Prospective cohort | Mixed PICU | 214 | Median, 10.1 y (IQR, 5.1-14.1 y) | CBCL at 1 y |

| Boeschoten et al,30 2020 | The Netherlands | Prospective cohort | Severe asthma | 20 (vs 62 in general ward) | PICU: median, 8 y (IQR, 6-12 y); general ward: median, 5 y (IQR, 3-6 y) | CBCL at 5 mo |

| Attention deficit | ||||||

| Verstraete et al,7 2016 | Belgium | Retrospective cohort | Mixed PICU | 449 (vs 100 in healthy control group) | Development cohort: median, 3.4 y (IQR, 2.9-4.0 y); validation cohort: median, 3.3 y (IQR, 2.7-3.8 y) | ANTB at 4 y |

| Jacobs et al,50 2020d | Belgium, Canada, and the Netherlands | RCT | Mixed PICU | 684 (vs 369 in healthy control group) | Mean (SD), 7.3 (4.3) y | ANTB at 4 y |

| Mesotten et al,27 2012 | Belgium | RCT | Mixed PICU | 456 (vs 216 in healthy control group) | Median, 5.2 y (IQR, 4.2-8.3 y) | ANTB at 3 y |

| Developmental delay | ||||||

| Berger et al,14 2018 | US | Prospective cohort | Pertussis | 111 | 86% <3 mo | MSEL at 1 y |

| Ballweg et al,15 2007 | US | Retrospective cohort | Cardiac surgery | 188 | Mean (SD), 38.5 (2.1) wk | MDI at 6 mo; PDI at 6 mo |

| Depression | ||||||

| Bronner et al,39 2009 | The Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | Septic shock | 48 | Median, 4.2 y (IQR, 0-17.0 y) | CDI at 6.5 y |

| Memory impairment | ||||||

| Verstraete et al,7 2016 | Belgium | Retrospective cohort | Mixed PICU | 449 (vs 100 in healthy control group) | Development cohort: median, 3.4 y (IQR, 2.9-4.0 y); validation cohort: median, 3.3 y (IQR, 2.7-3.8 y) | CMS at 4 y |

| Jacobs et al,50 2020d | Belgium, Canada, and the Netherlands | RCT | Mixed PICU | 684 (vs 369 in healthy control group) | Mean (SD), 7.3 (4.3) y | CMS at 4 y |

| Mesotten et al,27 2012 | Belgium | RCT | Mixed PICU | 198 (vs 124 in healthy control group) | Median, 5.2 y (IQR, 4.2-8.3 y) | CMS at 3 y |

Abbreviations: ANTB, Amsterdam Neuropsychological Tasks battery; BRIEF, Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; CDI, Children’s Depression Inventory; CIES, Children’s Impact of Events Scale; CMFS, Child Medical Fear Scale; CMS, Children’s Memory Scale; CPSS, Child PTSD Symptom Scale; CRIES, Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale; CRTI, Children’s Response to Trauma Inventory; MDI, Mental Developmental Index; MSEL, Mullen Scales of Early Learning; PDI, Psychomotor Developmental Index; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; RCT, randomized clinical trial; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children; TSCYC, Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children; WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; WIS, Wechsler Intelligence Scale; WISC, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children; WPPSI, Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence; WPPSI-R, Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised.

Low risk of bias for at least 5 domains was found in 524,26,27,49,50 of 9 RCTs.24,25,26,27,28,49,50,53,54 Two7,12 of 34 observational studies5,7,10,12,13,14,15,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,51,52,55,56,57,58,59 were deemed of good quality. Additional details regarding risk of bias and study quality assessments are provided in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Psychological Outcomes

Emotional and Behavioral Problems

Overall, 50 of 226 children (22.1%)13 to 46 of 160 children (28.8%)29 admitted to the PICU had emotional and behavioral problems at 1 year of follow-up.13,28,29 A total of 84 of 1105 children (7.6%)43 had abnormal scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire60 (which evaluates emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behavior; score range, 0-50 points, with higher scores indicating greater emotional and behavioral problems) at the 6-year follow-up (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

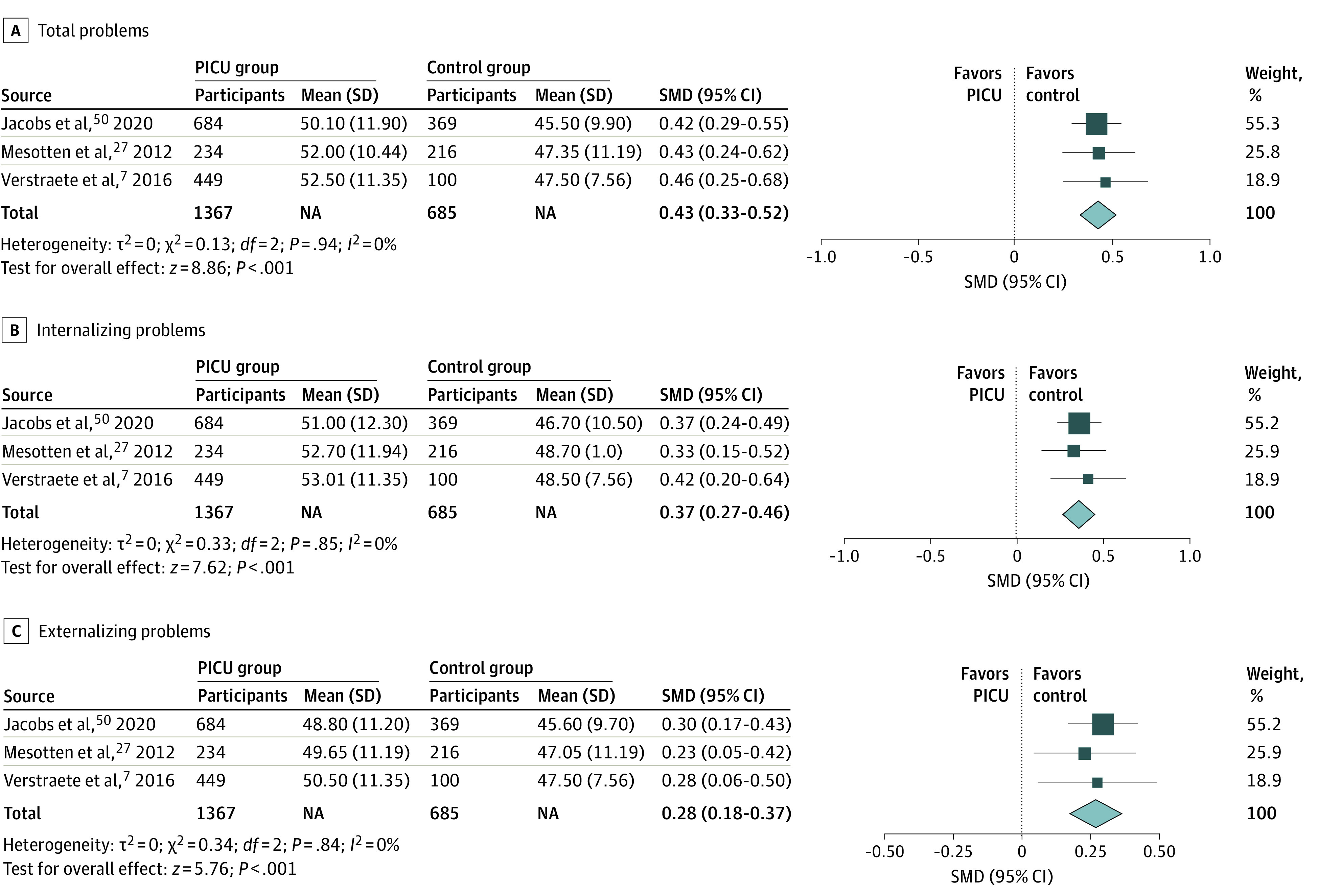

Among 22 total studies5,7,10,13,26,27,28,29,30,31,36,37,40,43,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55 reporting emotional and behavioral problems, 7 studies7,26,27,30,31,50,52 used the Child Behavior Checklist61 (which measures total problems, internalizing problems, and externalizing problems (mean [SD] T score, 50 [10] points, with higher scores indicating more behavioral problems) (Table). Children in mixed PICU cohorts scored significantly worse than healthy children on all 3 domains of the Child Behavior Checklist at 2 years (no meta-analysis for 2-year data was conducted because these results were obtained from only 1 study).26 Pooling of 4-year follow-up results from 3 studies7,27,50 (1367 children in mixed PICU cohorts vs 685 healthy children) revealed that children admitted to the PICU had worse scores for total problems (mean, 51.69 points [95% CI, 50.37-53.01 points] vs 46.66 points [95% CI, 45.20-48.13 points]; P < .001), internalizing problems (mean, 52.33 points [95% CI, 51.13-53.52 points] vs 47.87 points [95% CI, 46.50-49.23 points]; P < .001), and externalizing problems (mean, 49.72 points [95% CI, 48.80-50.63 points] vs 46.61 points [95% CI, 45.37-47.84 points]; P < .001) compared with healthy children (Figure 2). Ten years after PICU admission, 7 of 120 children (5.8%) admitted for septic shock continued to exhibit behavioral problems.52

Figure 2. Emotional and Behavioral Problems at 4-Year Follow-up.

Results from random-effects model. Emotional and behavioral problems were assessed using the Child Behavior Checklist. NA indicates not applicable; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; and SMD, standardized mean difference.

Compared with children in mixed PICU cohorts, those admitted after cardiac arrest had worse long-term emotional and behavioral outcomes. A total of 14 of 16 children with cardiac arrest (87.5%) who received cardiac extracorporeal life support experienced substantial behavioral problems 4 years later.37

The presence of congenital heart disease was associated with worse long-term emotional and behavioral outcomes. Overall, 17 of 72 children (23.7%) admitted to the PICU for congenital heart disease had behavioral problems (measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire) at 15 years after admission, with worse scores on the emotional symptoms subscale (25 of 76 children [32.9%]) and peer problems subscale (29 of 76 children [38.1%]).40 These results contrasted with those of children in mixed PICU cohorts, among whom only 84 of 1105 children (7.6%) had abnormal scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire at 6 years.43

Cognitive Impairment

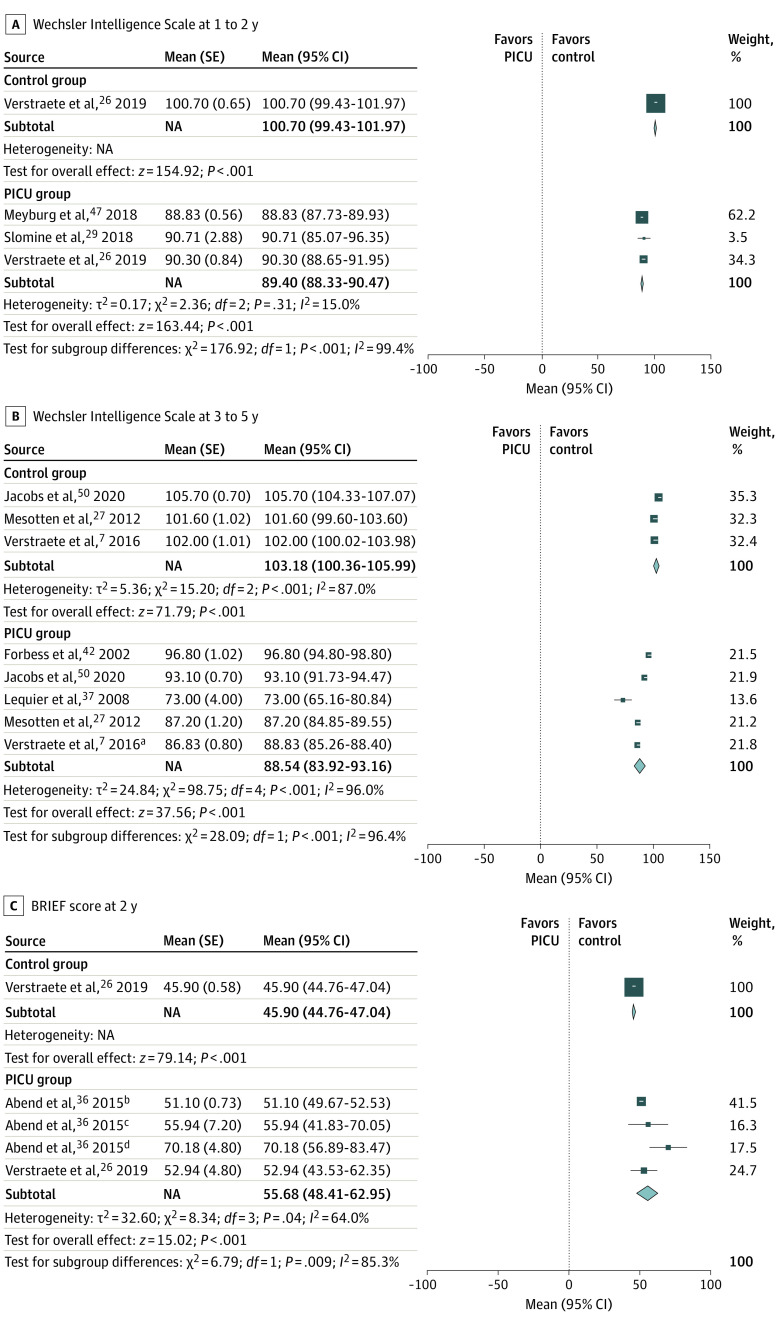

Overall, 28 of 226 children (12.4%)13 to 28 of 111 children (25.2%)29 in mixed PICU cohorts either did not receive passing scores for age-appropriate cognitive performance13 or had global cognitive impairment29 at 1 year after PICU admission. Age-corrected standard IQ scores on Wechsler intelligence scales (including the Wechsler Intelligence Scale,62 the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence,63 the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence,64 and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children65; mean [SD] standard IQ score, 100 [15] points for all scales) from 8 studies7,26,27,29,37,42,47,50 were pooled. At 1 to 2 years of follow-up, children admitted to the PICU had lower IQ scores than healthy children (mean, 89.40 points [95% CI, 88.33-90.47 points] vs 100.70 points [95% CI, 99.43-101.97 points]; P < .001) (Figure 3A). At 3 to 5 years, children admitted to the PICU continued to have lower scores compared with healthy children (mean, 88.54 points [95% CI, 83.92-93.16 points] vs 103.18 points [95% CI, 100.36-105.99 points]; P < .001) (Figure 3B). Children in mixed PICU cohorts also scored higher on the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function scale66 (mean [SD] score, 50 [10] points, with higher scores indicating worse executive function) compared with healthy children (mean, 55.68 points [95% CI, 83.92-93.16 points] vs 45.90 points [95% CI, 44.76-47.04 points]; P < .01) at 2 years,26,36 revealing worse executive function in areas such as inhibition, flexibility, emotional control, planning, and meta-cognition67 (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Cognitive Impairment at 1- to 5-Year Follow-up.

Results from random-effects model. BRIEF indicates Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function; NA, not applicable; and PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

aCohort used for model development in the study.

bPediatric patients with electrographic seizures who received cardiac surgery.

cPediatric patients with electrographic status epilepticus who received cardiac surgery.

dPediatric patients with no seizures who received cardiac surgery.

Cognitive impairment was more common among 2 subsets of children. Among 44 children admitted to the PICU after cardiac arrest, 20 children (45.4%) had IQ scores lower than 70 points at 1 year of follow-up,51 and 8 of 16 children (50.0%) had IQ scores lower than 70 points at 4 years of follow-up.37 Among 77 children admitted to the PICU for congenital heart disease, 23 children (29.9%) had IQ scores lower than 80 points at 15 years after admission.40 A total of 8 of 120 children (6.7%) admitted for septic shock also had IQ scores lower than 85 points at 10 years after PICU admission52 (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

PTSD and Anxiety

Overall, 6 of 60 children (10.0%)10 to 31 of 102 children (30.4%)24 admitted to the PICU met the criteria for PTSD at 3 to 6 months of follow-up,10,24,30,33,35,58 and 35 of 272 children (12.9%)34 to 7 of 38 children (18.4%)32 met the criteria for PTSD at 6 to 12 months of follow-up12,32,33,34 (eTable 4 in the Supplement). No statistical difference in the number of children with PTSD was found when comparing those admitted to the PICU (5 of 28 children [17.9%]) with those who survived a major fire (68 of 355 children [19.0%]; P = .98) at 9 months of follow-up, even after correcting for sex and age.33 At 6.5 years of follow-up, female children admitted to the PICU performed better than healthy children (mean [SD], 28.3 [6.7] points vs 33.0 [6.5] points)39 on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children,68 which measures both state anxiety (ie, anxiety level about an event) and trait anxiety (ie, anxiety level as a personality characteristic), with scores ranging from 20 to 60 points (higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety). No significant difference was found in male children admitted to the PICU39 (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Memory Impairment

At 5 months of follow-up, children admitted to the PICU scored worse than healthy children on the spatial working memory (between errors) subtest (mean [SD], −0.70 [0.80] points vs 0.07 [0.80] points; P = .01), the spatial working memory (strategy) subtest (mean [SD], −0.63 [0.67] points vs 0.08 [1.22] points; P = .05), and the rapid visual information processing subtest (mean [SD], −2.78 [1.65] points vs −1.10 [1.36] points; P = .009) of the Cambridge Neuropsychological Testing Automated Battery69 (which measures memory using z scores, with higher scores indicating better memory).46 Children admitted to the PICU also performed worse than healthy children on the total score (mean [SD], 7.80 [2.04] points vs 10.00 [3.55] points; P = .05), learning subtest (mean [SD], 8.20 [1.93] points vs 10.40 [3.29] points; P = .03), and delayed recognition subtest (mean [SD], 9.67 [2.44] points vs 11.60 [1.06] points; P = .009) of the Children’s Memory Scale70 (which measures verbal memory; mean [SD] score, 10 [3] points, with higher scores indicating better memory)46 (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Pooling of 3 to 4 years of follow-up results from 3 studies7,27,50 revealed that children admitted to the PICU scored worse than healthy children on the subscales for memory span (mean, 8.11 points [95% CI, 7.49-8.73 points] vs 9.50 points [95% CI, 8.83-10.16 points]; P = .003), working memory (mean, 9.05 points [95% CI, 8.57-9.54 points] vs 10.34 points [95% CI, 10.14-10.54 points]; P < .001), learning index (mean, 90.18 points [95% CI, 87.84-92.51 points] vs 100.02 [95% CI, 99.77-100.27 points]; P < .001), verbal immediate index (mean, 0.34 points [95% CI, 0.32-0.37 points] vs 0.47 points [95% CI 0.40-0.53 points]; P < .001), and verbal delayed index (mean, 0.29 points [95% CI, 0.25-0.32 points] vs 0.40 points [95% CI, 0.39-0.42 points]; P < .001) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). No difference was found on the verbal delayed recognition index (mean, 0.93 points [95% CI, 0.90-0.95 points] vs 0.96 points [95% CI, 0.93-0.99 points]; P = .12).

Attention Deficit, Developmental Delay, and Depression

At 3 to 4 years, children admitted to the PICU scored worse than healthy children27,50 on the Amsterdam Neuropsychological Tasks battery,71 which measures attention, motor coordination, and executive functioning through reaction times and accuracy (score measured in milliseconds, with shorter reaction times indicating better attention) (Table). Meta-analysis was not performed for the results of the Amsterdam Neuropsychological Tasks battery because too few studies used this measurement tool, and the data were of inadequate quality (eg, different scales and large variation in range between different studies) to be pooled.

At 1 year of follow-up, PICU admissions for pertussis14 were associated with language delays (23 of 111 children [20.7%] had expressive language delay and 16 of 111 children [14.4%] had receptive language delay), and PICU admissions after cardiac surgery15 were associated with neurodevelopmental delays. One study39 found that PICU admission for septic shock was associated with less depression at 6.5 years of follow-up compared with healthy children of similar ages (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that psychological repercussions after PICU admission were common. Emotional and behavioral problems5,7,10,13,26,27,28,29,30,31,36,37,40,43,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55 and cognitive impairment7,13,26,27,29,36,37,39,40,41,42,45,47,49,50,51,52,56,57 were most frequently reported, but PTSD,5,10,12,24,30,32,33,34,35,58,59 anxiety,25,39 memory impairment,7,27,46,50 attention deficit,7,27,50 developmental delay,14,15,38 and depression39 were also noted. Of greater concern was the finding that many of these psychological problems persisted among children for many years after their PICU admission for critical illness.40,41,52,56,57

The types of psychological outcomes experienced by children admitted to the PICU varied with time. At 3 to 6 months of follow-up, PTSD was the most common outcome reported,5,10,12,24,30,33,35,58,59 but no reports of PTSD were found beyond 1 year of follow-up.12 Developmental delay,14,15,38 attention deficit,7,27,50 and memory impairment7,27,46,50 were observed among children admitted to the PICU in the intermediate long-term (ie, 1-4 years after admission). Developmental delay was reported between 6 and 20 months after PICU admission,14,15,38 whereas attention deficit7,27,50 and memory impairment7,27,50 were reported 3 to 4 years later. Cognitive impairment, emotional problems, and behavioral problems had the most long-lasting consequences for children admitted to the PICU, extending for 10 to 15 years after admission.40,52 These psychological repercussions suggest that children previously admitted to the PICU may continue to be at risk of substantial morbidity for years after discharge. Identifying children with high risk of developing psychological sequelae and providing them with early intervention is important to improve clinical outcomes among those who are vulnerable.

One common theme identified across studies was that younger age at PICU admission was associated with worse psychological outcomes. Among children who were admitted to the PICU for cardiac surgery42 and septic shock,39 younger age was associated with lower IQ scores and greater cognitive impairment. Younger children in mixed PICU cohorts also had a higher number of externalizing problems,57 rule-breaking behaviors,57 and behavioral problems.43 One possible explanation for these findings is that younger children may experience a lower sense of control over their health after PICU admission.5 This vulnerability may manifest as greater avoidance of thoughts and feelings,59 producing more long-term psychological morbidities. Consistent with this possibility, a single-center study29 of 160 patients conducted in the US found a higher correlation between global cognition and problem behaviors among younger children compared with older children, further suggesting that insufficient psychological reserves may place younger children at higher risk of developing severe post-PICU psychological sequelae.

Another notable observation was sex differences in the psychological problems found among children admitted to the PICU. Between 3 and 6 months after PICU admission, girls experienced more internalizing, externalizing, and posthospital behavior changes than boys.53 Admission to the PICU also appeared to be protective against anxiety for girls at 6.5 years of follow-up, with girls having significantly lower anxiety levels than healthy children, despite no statistical differences found among their male counterparts.39 After a decade, the types of behavioral problems experienced by both boys and girls were also different. Boys admitted to the PICU experienced more total problems, externalizing problems, intrusive behavior when interacting with other people, rule-breaking behaviors, attention deficit, and emotional withdrawal than girls admitted to the PICU,57 whereas girls reported more emotional symptoms and a higher number of prosocial behaviors as measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.40 The risk of developing different psychological outcomes varied by sex, suggesting that interventions tailored to patients’ distinct demographic characteristics may be likely to produce the greatest benefit. In a previous systematic review72 examining interventions to reduce psychiatric morbidities among children after PICU discharge, strategies such as psychoeducational programs, parental support after discharge, and close follow-up to identify children experiencing problems, especially among those at high risk, have been proposed.

Clinical demographic factors were also found to be associated with the severity of subsequent psychological morbidities. Among children in mixed PICU cohorts, those admitted for cardiac arrest or congenital heart disease experienced greater emotional and behavioral problems37,40 as well as cognitive impairment,37,40,51 whereas greater use of indwelling medical devices was associated with increased prevalence of attention deficit.7 However, we noted a paucity of literature regarding other important factors. Studies evaluating the association between severity of illness scores (eg, Pediatric Index of Mortality or Pediatric Risk of Mortality scores) and psychological outcomes were lacking. Among adults, invasive mechanical ventilation has been associated with a higher number of PTSD symptoms,73 yet similar studies of children admitted to the PICU were lacking. More studies investigating the association between important clinical variables and psychological outcomes among children admitted to the PICU are needed for better risk stratification.

The findings of the present study lend further validation to the importance of the mental health problem domain of the PICS-p framework.11 The psychological difficulties encountered by children admitted to the PICU can be debilitating to their development and reduce their overall quality of health.74,75 Beyond improving physical health, medical teams may need to consider the psychological repercussions that can manifest from a child’s illness and PICU experience. More studies exploring risk factors associated with long-term psychological outcomes and early interventions to minimize psychological morbidities are necessary. Priority might be given to developing standardized definitions and measures for the various psychological outcomes so that results from subsequent studies and interventional clinical trials can be compared. Future studies are also needed to provide a better framework for identification of patients in the PICU who are at high risk of psychological morbidity. Although some of these factors have been identified in our systematic review (eg, younger age, sex, and PICU admission after cardiac arrest), more studies are necessary to examine the impact of factors such as severity of illness scores, sedation strategies, and other common PICU interventions.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. One limitation is the underrepresentation of certain PICU populations. All included studies were conducted in either North America, Europe, or Australia, whereas none were performed in Asia, South America, or Africa. Thus, the study sample underrepresented certain racial and ethnic communities who may experience different outcomes after PICU admission. Furthermore, the current literature does not adequately address the complex interaction between patients’ comorbidities, indications for PICU admissions, and critical care interventions and their consequences for adverse long-term psychological outcomes. For instance, consistent with a previous study,40 we found an association between the presence of congenital heart disease and long-term emotional and behavioral outcomes. This association is best interpreted within the clinical context in which approximately 25% of children with congenital heart disease are at high risk of developmental and cognitive sequalae, and almost all infants with critical congenital heart disease require PICU admission and interventions.76 The choice of comparison groups (eg, healthy children, children admitted to the general ward, and children who survived a major fire) was inconsistent across studies, which hindered our ability to compare their outcomes with those of children admitted to the PICU. This heterogeneity, together with the lack of description of individual and environmental risk factors for psychological sequelae in the included studies, limit the generalizability of our findings, especially over a longer follow-up period.

Another limitation is the lack of studies examining the association between indications for PICU admission and psychological outcomes. It is likely that children admitted for emergency indications would have different outcomes from those of children admitted electively after surgery. Although multiple studies12,24,25,26,27,28,29,32,43,59 documented indications for PICU admission, none explored the association between various psychological outcomes and indications for admission. Furthermore, we had limited ability to pool results from different studies in this review because of the variety of measurement scales, scoring systems, and cutoffs used to assess each outcome. For example, cognitive impairment was defined by some studies as 2 SDs below the population mean,29 whereas other studies defined cognitive impairment as an IQ score lower than 70 points,37,41,51 80 points,40 or 85 points.52 To overcome this limitation, absolute scores rather than reported outcomes were used in the meta-analysis.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis found a substantial burden of psychological sequelae among children who were previously admitted to the PICU, suggesting that risk stratification and early intervention for high-risk groups are needed to minimize long-term psychological morbidities. The findings also revealed the complexity and prevalence of psychological sequelae experienced by children admitted to the PICU and highlighted the importance of considering psychological outcomes among children who survive critical illness. Health care centers offering PICU facilities may consider adopting the necessary infrastructure to support psychological assessments, with an emphasis on long-term follow-up plans for children admitted to the PICU. These programs would be most beneficial if they were not only confined to the PICU but also involved a multidisciplinary team of psychologists, medical social workers, caregivers, and educators, extending longitudinally even after a child’s discharge from the PICU.

eTable 1. PRISMA 2020 Checklist

eTable 2. Detailed Search Strategy

eTable 3. Risk of Bias Assessment

eTable 4. Summary of Included Studies

eFigure 1. Global Distribution of Single-Center and Multicenter Studies Included in Review

eFigure 2. Random-Effects Model for Memory Impairment Measured at 4-Year Follow-up Using Children’s Memory Scale

eReferences

References

- 1.Davis P, Stutchfield C, Evans TA, Draper E. Increasing admissions to paediatric intensive care units in England and Wales: more than just rising a birth rate. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(4):341-345. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraser LK, Parslow R. Children with life-limiting conditions in paediatric intensive care units: a national cohort, data linkage study. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(6):540-547. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-312638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straney LD, Schlapbach LJ, Yong G, et al. ; Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Paediatric Study Group . Trends in PICU admission and survival rates in children in Australia and New Zealand following cardiac arrest. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(7):613-620. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davydow DS, Richardson LP, Zatzick DF, Katon WJ. Psychiatric morbidity in pediatric critical illness survivors: a comprehensive review of the literature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(4):377-385. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rennick JE, Johnston CC, Dougherty G, Platt R, Ritchie JA. Children’s psychological responses after critical illness and exposure to invasive technology. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(3):133-144. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200206000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milette IH, Carnevale FA. I’m trying to heal...noise levels in a pediatric intensive care unit. Dynamics. 2003;14(4):14-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verstraete S, Vanhorebeek I, Covaci A, et al. Circulating phthalates during critical illness in children are associated with long-term attention deficit: a study of a development and a validation cohort. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(3):379-392. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4159-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koopman HM, Baars RM, Chaplin J, Zwinderman KH. Illness through the eyes of the child: the development of children’s understanding of the causes of illness. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55(3):363-370. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crisp J, Ungerer JA, Goodnow JJ. The impact of experience on children’s understanding of illness. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21(1):57-72. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.1.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rennick JE, Morin I, Kim D, Johnston CC, Dougherty G, Platt R. Identifying children at high risk for psychological sequelae after pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5(4):358-363. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000128603.20501.0D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manning JC, Pinto NP, Rennick JE, Colville G, Curley MAQ. Conceptualizing post intensive care syndrome in children—the PICS-p framework. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(4):298-300. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rees G, Gledhill J, Garralda ME, Nadel S. Psychiatric outcome following paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission: a cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(8):1607-1614. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2310-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gemke RJ, Bonsel GJ, van Vught AJ. Long-term survival and state of health after paediatric intensive care. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73(3):196-201. doi: 10.1136/adc.73.3.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger JT, Villalobos ME, Clark AE, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network . Cognitive development one year after infantile critical pertussis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(2):89-97. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballweg JA, Wernovsky G, Ittenbach RF, et al. Hyperglycemia after infant cardiac surgery does not adversely impact neurodevelopmental outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84(6):2052-2058. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.06.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rennick JE, Rashotte J. Psychological outcomes in children following pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization: a systematic review of the research. 2009;13(2):128-149. doi: 10.1177/1367493509102472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopes-Junior LC, de Paula Rosa MADR, de Lima RAG. Psychological and psychiatric outcomes following PICU admission: a systematic review of cohort studies. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(1):e58-e67. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PloS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senn SJ. Overstating the evidence: double counting in meta-analysis and related problems. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. ; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group . The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of onrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2000. Accessed April 18, 2021. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 23.Modesti PA, Reboldi G, Cappuccio FP, et al. Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2016;11(1):e0147601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson RS, Asaro LA, Hertzog JH, et al. ; RESTORE Study Investigators and the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network . Long-term outcomes after protocolized sedation versus usual care in ventilated pediatric patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(11):1457-1467. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1768OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rennick JE, Stremler R, Horwood L, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of an intervention to promote psychological well-being in critically ill children: soothing through touch, reading, and music. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(7):e358-e366. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verstraete S, Verbruggen SC, Hordijk JA, et al. Long-term developmental effects of withholding parenteral nutrition for 1 week in the paediatric intensive care unit: a 2-year follow-up of the PEPaNIC international, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(2):141-153. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30334-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mesotten D, Gielen M, Sterken C, et al. Neurocognitive development of children 4 years after critical illness and treatment with tight glucose control: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;308(16):1641-1650. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.12424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melnyk BM, Alpert-Gillis L, Feinstein NF, et al. Creating opportunities for parent empowerment: program effects on the mental health/coping outcomes of critically ill young children and their mothers. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):e597-e607. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slomine BS, Silverstein FS, Christensen JR, et al. Neuropsychological outcomes of children 1 year after pediatric cardiac arrest: secondary analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(12):1502-1510. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boeschoten SA, Dulfer K, Boehmer ALM, et al. ; Dutch Collaborative PICU Research Network (SKIC) . Quality of life and psychosocial outcomes in children with severe acute asthma and their parents. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55(11):2883-2892. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biagas KV, Hinton VJ, Hasbani NR, et al. ; HALF-PINT Trial Study investigators; PALISI Network . Long-term neurobehavioral and quality of life outcomes of critically ill children after glycemic control. J Pediatr. 2020;218:57-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.10.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colville GA, Pierce CM. Children’s self-reported quality of life after intensive care treatment. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(2):e85-e92. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182712997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bronner MB, Knoester H, Bos AP, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in children after paediatric intensive care treatment compared to children who survived a major fire disaster. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Brocque RM, Dow BL, McMahon H, et al. The course of posttraumatic stress in children: examination of symptom trajectories and predictive factors following admission to pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21(7):e399-e406. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson LP, Lachman SE, Li SW, Gold JI. The effects of family functioning on the development of posttraumatic stress in children and their parents following admission to the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(4):e208-e215. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abend NS, Wagenman KL, Blake TP, et al. Electrographic status epilepticus and neurobehavioral outcomes in critically ill children. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:238-244. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lequier L, Joffe AR, Robertson CMT, et al. ; Western Canadian Complex Pediatric Therapies Program Follow-up Group . Two-year survival, mental, and motor outcomes after cardiac extracorporeal life support at less than five years of age. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136(4):976-983. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Limperopoulos C, Majnemer A, Shevell MI, et al. Predictors of developmental disabilities after open heart surgery in young children with congenital heart defects. J Pediatr. 2002;141(1):51-58. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.125227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bronner MB, Knoester H, Sol JJ, Bos AP, Heymans I, Grootenhuis MA. An explorative study on quality of life and psychological and cognitive function in pediatric survivors of septic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10(6):636-642. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181ae5c1a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shevell AH, Sahakian SK, Nguyen Q, Fontela P, Rohlicek C, Majnemer A. Associations between postoperative management in the critical care unit and adolescent developmental outcomes following cardiac surgery in infancy: an exploratory study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21(11):e1010-e1019. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buysse CMP, Raat H, Hazelzet JA, et al. Long-term health status in childhood survivors of meningococcal septic shock. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(11):1036-1041. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forbess JM, Visconti KJ, Hancock-Friesen C, Howe RC, Bellinger DC, Jonas RA. Neurodevelopmental outcome after congenital heart surgery: results from an institutional registry. Circulation. 2002;106(12)(suppl 1):I95-I102. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000032915.33237.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kyosti E, Ala-Kokko TI, Ohtonen P, et al. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire assessment of long-term psychological outcome in children after intensive care admission. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(11):e496-e502. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones S, Rantell K, Stevens K, et al. ; United Kingdom Pediatric Intensive Care Outcome Study Group . Outcome at 6 months after admission for pediatric intensive care: a report of a national study of pediatric intensive care units in the United Kingdom. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):2101-2108. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shein SL, Roth E, Pace E, Slain KN, Wilson-Costello D. Long-term neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes of normally developing children requiring PICU care for bronchiolitis. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2020;10(4):282-288. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1716856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elison S, Shears D, Nadel S, Sahakian B, Garralda ME. Neuropsychological function in children following admission to paediatric intensive care: a pilot investigation. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(7):1289-1293. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1093-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyburg J, Ries M, Zielonka M, et al. Cognitive and behavioral consequences of pediatric delirium: a pilot study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(10):e531-e537. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fiser DH, Long N, Roberson PK, Hefley G, Zolten K, Brodie-Fowler M. Relationship of pediatric overall performance category and pediatric cerebral performance category scores at pediatric intensive care unit discharge with outcome measures collected at hospital discharge and 1- and 6-month follow-up assessments. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(7):2616-2620. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guiza F, Vanhorebeek I, Verstraete S, et al. Effect of early parenteral nutrition during paediatric critical illness on DNA methylation as a potential mediator of impaired neurocognitive development: a pre-planned secondary analysis of the PEPaNIC international randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(3):288-303. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30046-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jacobs A, Dulfer K, Eveleens RD, et al. Long-term developmental effect of withholding parenteral nutrition in paediatric intensive care units: a 4-year follow-up of the PEPaNIC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(7):503-514. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30104-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meert K, Slomine BS, Silverstein FS, et al. ; Therapeutic Hypothermia after Paediatric Cardiac Arrest (THAPCA) Trial Investigators . One-year cognitive and neurologic outcomes in survivors of paediatric extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2019;139:299-307. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buysse CMP, Vermunt LCAC, Raat H, et al. Surviving meningococcal septic shock in childhood: long-term overall outcome and the effect on health-related quality of life. Crit Care. 2010;14(3):R124. doi: 10.1186/cc9087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Small L, Melnyk BM. Early predictors of post-hospital adjustment problems in critically ill young children. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(6):622-635. doi: 10.1002/nur.20169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Small L, Melnyk BM, Sidora-Arcoleo K. The effects of gender on the coping outcomes of young children following an unanticipated critical care hospitalization. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2009;14(2):112-122. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00184.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vermunt LCAC, Buysse CMP, Joosten KFM, Hazelzet JA, Verhulst FC, Utens EMWJ. Behavioural, emotional, and post-traumatic stress problems in children and adolescents, long term after septic shock caused by Neisseria meningitidis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2008;47(pt 3):251-263. doi: 10.1348/014466507X258868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vermunt LCAC, Buysse CMP, Aarsen FK, et al. Long-term cognitive functioning in children and adolescents who survived septic shock caused by Neisseria meningitidis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2009;48(pt 2):195-208. doi: 10.1348/014466508X391094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vermunt LC, Buysse CM, Joosten KF, et al. Survivors of septic shock caused by Neisseria meningitidis in childhood: psychosocial outcomes in young adulthood. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(6):e302-e309. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182192d7f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dow BL, Kenardy JA, Le Brocque RM, Long DA. The utility of the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale in screening for concurrent PTSD following admission to intensive care. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25(5):602-605. doi: 10.1002/jts.21742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dow BL, Kenardy JA, Le Brocque RM, Long DA. The diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder in school-aged children and adolescents following pediatric intensive care unit admission. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2013;23(9):614-619. doi: 10.1089/cap.2013.0044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stone LL, Janssens JMAM, Vermulst AA, Van Der Maten M, Engels RCME, Otten R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: psychometric properties of the parent and teacher version in children aged 4-7. BMC Psychol. 2015;3(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0061-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, University of Vermont; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wechsler D. WAIS-R: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised. Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wechsler D. WPPSI: Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. Psychological Corporation; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. Psychological Corporation: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. Psychological Corporation; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baron IS. Behavior rating inventory of executive function. Child Neuropsychol. 2000;6(3):235-238. doi: 10.1076/chin.6.3.235.3152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spielberger CD, Edwards CD, Lushene R, Monturoi J, Platzek D. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children. Mind Garden; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sandberg MA. Cambridge Neuropsychological Testing Automated Battery. In: Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B, eds. Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. Springer; 2011. Accessed December 4, 2021.

- 70.Cohen MJ. Children’s Memory Scale. Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Sonneville LMJ. Handbook Amsterdam Neuropsychological Tasks (ANT). ResearchGate. Translation project. May 17, 2016. Updated May 12, 2021. Accessed April 18, 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/project/Handbook-Amsterdam-Neuropsychological-Tasks-ANT

- 72.Baker SC, Gledhill JA. Systematic review of interventions to reduce psychiatric morbidity in parents and children after PICU admissions. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(4):343-348. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shaw RJ, Harvey JE, Bernard R, Gunary R, Tiley M, Steiner H. Comparison of short-term psychological outcomes of respiratory failure treated by either invasive or non-invasive ventilation. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):586-591. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(09)70860-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cunha F, Mota T, Teixeira-Pinto A, et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life changes in survivors to pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(1):e8-e15. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31826012b4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aspesberro F, Mangione-Smith R, Zimmerman JJ. Health-related quality of life following pediatric critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(7):1235-1246. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3780-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bellinger DC, Wypij D, Rivkin MJ, et al. Adolescents with d-transposition of the great arteries corrected with the arterial switch procedure: neuropsychological assessment and structural brain imaging. Circulation. 2011;124(12):1361-1369. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.026963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. PRISMA 2020 Checklist

eTable 2. Detailed Search Strategy

eTable 3. Risk of Bias Assessment

eTable 4. Summary of Included Studies

eFigure 1. Global Distribution of Single-Center and Multicenter Studies Included in Review

eFigure 2. Random-Effects Model for Memory Impairment Measured at 4-Year Follow-up Using Children’s Memory Scale

eReferences