Abstract

In patients with non–small-cell lung cancer treated with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agents, no specific radiation parameter was significantly associated with immune-related (IR) pneumonitis. We identify on subset analysis of patients who developed IR pneumonitis and received chest radiation, patients were numerically more likely to have received chest radiation with curative intent than with palliative intent (89% vs. 11 that approached statistical significance.

Purpose:

To investigate the relationship between radiotherapy (RT), in particular chest RT, and development of immune-related (IR) pneumonitis in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-LI).

Patients and Methods:

Between June 2011 and July 2017, NSCLC patients treated with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 at a tertiary-care academic cancer center were identified. Patient, treatment, prior RT (intent, technique, timing, courses), and IR pneumonitis details were collected. Treating investigators diagnosed IR pneumonitis clinically. Diagnostic IR pneumonitis scans were overlaid with available chest RT plans to describe IR pneumonitis in relation to prior chest RT. We evaluated associations between patient, treatment, RT details, and development of IR pneumonitis by Fisher exact and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

Results:

Of the 188 NSCLC patients we identified, median follow-up was 6.78 (range, 0.30–79.3) months and median age 66 (range, 39–91) years; 54% (n = 102) were male; and 42% (n = 79) had stage I-III NSCLC at initial diagnosis. Patients received anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy (n = 127, 68%) or PD-I/PD-LI -based combinations (n = 61, 32%). In the entire cohort, 70% (132/188) received any RT, 53% (100/188) chest RT, and 37% (70/188) curative-intent chest RT. Any grade IR pneumonitis occurred in 19% (36/188; 95% confidence interval, 13.8–25.6). Of those who developed IR pneumonitis and received chest RT (n = 19), patients were more likely to have received curative-intent versus palliative-intent chest RT (17/19, 89%, vs. 2/19, 11%; P = .051). Predominant IR pneumonitis appearances were ground-glass opacities outside high-dose chest RT regions.

Conclusion:

No RT parameter was significantly associated with IR pneumonitis. On subset analysis of patients who developed IR pneumonitis and who had received prior chest RT, IR pneumonitis was more common in patients who received curative-intent chest RT. Attention should be paid to NSCLC patients receiving curative-intent RT followed by anti –PD-I/PD-LI agents.

Keywords: Anti–PD-1 /PD-LI therapy, Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab, Pneumonitis, Radiation

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) directed against programmed cell death 1 (PD-I) and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-LI) have improved survival for patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1–3 In addition, these agents have a mild overall toxicity profile. Despite this, 5% to 10% of patients may experience immune-related (IR) adverse events, which can be severe and potentially fatal.4

Pneumonitis is a focal or diffuse inflammation of the lung parenchyma,5 and its association with ICIs was first reported in a case report of 3 patients who received anti–PD-1 antibodies for the treatment of melanoma.6 Pneumonitis accounted for 3 treatment-related deaths (1%) in an early phase study of nivolumab.7 The reported incidence of IR pneumonitis after anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy ranges from 1% to 10%,8,9 with a higher incidence among those receiving combination immunotherapy.10,11 The median time to onset of IR pneumonitis is 2 to 3 months, with a wide range from less than 1 month to more than 27 months after initiation of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy.8–10

Radiotherapy (RT) is a standard treatment modality provided to patients with NSCLC; it may be administered with either curative or palliative intent. Consequently, there are variations in RT dosing and delivery techniques that may include simple 2- to 3-beam conformal arrangements for palliative treatments or highly modulated curative-intent treatments. Preclinical studies and clinical observations support potential immunologic synergy between RT and ICIs.12,13 Because RT delivered to the chest may cause its own pneumonitis, there is a theoretical concern for enhanced pulmonary toxicity in NSCLC patients receiving subsequent anti–PD-1/PD-Ll therapy. In an analysis of 97 NSCLC patients from the KEYNOTE-OOI phase 1 trial, 8% (2/24) of patients who received prior chest RT developed IR pneumonitis, compared to 1% (1/73) of patients who had not received prior chest RT.14 While these observations suggest a potential relationship between prior chest RT and the development of IR pneumonitis, the absolute numbers of IR pneumonitis cases were limited, and further studies are needed to explore associations between specific RT parameters and the development of IR pneumonitis. Moreover, the spatial distribution between IR pneumonitis and irradiated lung regions has not been evaluated.

We have previously reported on non–radiation-related clinical factors affecting the incidence risk rates of IR pneumonitis and overall survival (OS) among those who developed IR pneumonitis in a large series of NSCLC patients.15,16 Herein, we assess associations between RT intent, technique, and timing with the development of IR pneumonitis in patients treated with prior RT, and in particular chest RT. We also explore the distribution and appearance of radiographic IR pneumonitis as well as RT dose regions in the chest.

Patients and Methods

Patients with advanced NSCLC treated with anti–PD-1 /PD-LI therapy at Johns Hopkins University between January 2011 and June 2017 were identified. All patients received anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy either as the standard of care, or as part of an institutional review board (IRB)-approved clinical trial, and consented to have their data prospectively collected in an IRB-approved database.

The diagnosis of IR pneumonitis defined as clinical symptoms with or without radiologic inflammatory changes in the lung after ICI therapy, was clinically determined by the treating investigator (J.N., P.M.F., K.A.M., C.L.H., J.R.B., D.S.E., R.J.K.), and confirmed by an IR toxicity team consisting of a radiologist (C.L.), pulmonologist (K.S.), and second medical oncologist (J.N.) where relevant, as previously reported.15,16 IR pneumonitis was a diagnosis of exclusion, so any patients with confirmed or suspected alternative etiologies, including active pulmonary infection, progressive NSCLC, and RT pneumonitis, were excluded from the IR pneumonitis cohort. Active pulmonary infection was defined as pulmonary symptoms and/or radiologic changes that improved after empiric antibiotics or as infection confirmed by culture. Progressive NSCLC was determined radiologically, and in selected cases by pathologic confirmation. RT pneumonitis was defined as radiologic inflammatory changes found in or within close proximity to the irradiated lung tissue as per radiation plans with or without clinical symptoms within 12 months after chest RT.17,18 RT pneumonitis was radiologically and/or clinically determined by the treating provider with or without the input of a multidisciplinary team where appropriate.

All comparisons are between those who developed IR pneumonitis and those who did not.

Patient and tumor characteristics, treatment data, RT parameters, and IR pneumonitis data were collected by electronic data abstraction, confirmed by retrospective review, and stored in an IRB-approved database. Patient demographics, tumor histology, and cancer stage at diagnosis were collected. Treatment data included: prior cancer therapy received at diagnosis, anti–PD-1/PD-LI agent, secondary agent or agents where applicable, and date of first anti–PD-1/PD-LI dose. RT data included the following: RT dates, treatment location (chest vs. non-chest), RT intent (palliative vs. curative), dose (Gy) and fractions, RT technique (stereotactic body RT, intensity-modulated RT/volumetric modulated arc therapy, 2- or 3-dimensional conformal therapy), and chest RT dosimetric parameters (mean lung dose: the average dose in Gy delivered to lungs, MLD; percentage lung volume receiving 20 Gy, V20). For patients who received multiple courses of chest RT, the highest chest RT dose and dosimetric parameters identified were analyzed per patient. Curative-intent chest RT was defined as receipt of any prior definitive, postoperative, or consolidative chest RT, including but not limited to treatment for NSCLC. Details of RT received after development of IR pneumonitis were not included in this analysis. IR pneumonitis data collected included: date of first IR pneumonitis event and highest IR pneumonitis grade. Date of IR pneumonitis was defined as the date of diagnosis of clinical symptoms and/or radiographic findings, confirmed by the treating provider. IR pneumonitis grade reported using the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 4.0).

In order to describe the features of IR pneumonitis in relation to regions of prior irradiated lung, electronic RT plans were restored and rigidly fused with diagnostic chest computed tomographic (CT) scans using Velocity Al software (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA)19 in patients with IR pneumonitis who had prior chest RT at our institution only. For standardized comparison, RT doses were converted to equivalent doses in 2 Gy fractions20 using an α/β ratio of 3, acknowledging the limitations of this approach.21 Dose regions were defined as follows: high dose, > 45 Gy; intermediate dose, > 20 Gy; low dose, < 20 Gy; and outside the RT fall-off dose region, < 1 Gy. Overlaid isodose lines were then displayed on diagnostic chest CT scans. A thoracic radiologist (C.T.L.) evaluated these diagnostic CT scans in lung windows for radiographic features of inflammation (ground-glass opacities, GGOs; organizing pneumonia; centrilobular tree-in-bud nodularity) and fibrosis (combinations of masslike consolidation, volume loss, architecture distortion, traction bronchiectasis), and estimated the percentage involvement of CT findings within and outside of the standardized RT dose regions.

Associations between patient and treatment characteristics and the development of any grade IR pneumonitis was evaluated by the Fisher’s exact and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. OS was calculated from the date of first anti–PD-1/PD-L1 administration until date of death or last follow-up. To avoid survivorship bias, landmark analyses were performed to evaluate the role of IR pneumonitis and receipt of prior chest RT on survival.

Results

Patient Characteristics

One hundred eighty-eight patients with advanced NSCLC treated with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy were identified between 2011 and 2017 and are a subset of the 205 patients treated between 2007 and 2017 reported by us previously.15,16 The median age was 66 (range, 39–91) years. In the entire cohort, 54% (n = 102) were male, 78% (n = 147) were white, and 80% (n = 151) were former or current smokers. The majority of patients had lung adenocarcinomas (65%, n = 123). At the time of initial presentation, 13% (n – 25) of patients had stage I/II, 29% (n – 54) had stage III, and 58% (n = 109) had stage IV NSCLC. There were no differences in patient, tumor, or treatment characteristics between those who developed IR pneumonitis and those who did not (P > .05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics

| Characteristic | No IR Pneumonitis | IR Pneumonitis | All Patients | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 152 (80.9) | 36 (19.1) | 188 | |

| Patient Characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 83 (54.6) | 19 (52.8) | 102 (54.3) | |

| Female | 69 (45.4) | 17 (47.2) | 86 (45.7) | .86 |

| Age (Years) | ||||

| Median | 66.3 | 65.7 | 66.3 | |

| Range | 38.6–90.6 | 50.8–83.5 | 38.6–90.6 | .46 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 120 (78.9) | 27 (75) | 147 (78.2) | |

| African American | 28 (18.4) | 7 (19.4) | 35 (18.6) | |

| Asian | 2(1.3) | 1 (2–8) | 3(1.6) | |

| Other | 2(1.3) | 1 (2.8) | 3(1.6) | .48 |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Current | 11 (7.2) | 2 (5.6) | 13 (6.9) | |

| Former | 110(72.4) | 28 (77.8) | 138 (73.4) | |

| Never | 31 (20.4) | 6 (16.7) | 37 (19.7) | .90 |

| Median pack-years | 33 | 31.2 | 32.8 | .42 |

| Tumor Characteristics | ||||

| Tumor Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 105 (69.1) | 18 (50) | 123 (65.4) | |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | |

| Atypical carcinoid tumor | 2(1.3) | 0 | 2(1.1) | |

| Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | 2(1.3) | 3 (8.3) | 5(2.7) | |

| NSCLC NOS | 1 (0–7) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | |

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma | 2(1.3) | 1 (2.8) | 3(1.6) | |

| Sarcomatoid carcinoma | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | |

| Squamous-cell carcinoma | 38 (25) | 14 (38.9) | 52 (27.7) | .11 |

| Initial Stage | ||||

| I | 12 (7.9) | 1 (2–8) | 13 (6.9) | |

| II | 7 (4.6) | 5 (13.9) | 12 (6.4) | |

| III | 43 (28.3) | 11 (30.6) | 54 (28.7) | |

| IV | 90 (59.2) | 19 (52.8) | 109 (58) | .17 |

| Treatment Characteristics | ||||

| Treatment Naive Before Immunotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 19(12.5) | 8 (22.2) | 27 (14.4) | |

| No | 133 (87.5) | 28 (77.8) | 161 (85.6) | .18 |

| Prior Treatment at Initial Diagnosisa | ||||

| Surgery | ||||

| Yes | 30 (19.7) | 7 (19.4) | 37 (19.7) | |

| No | 122 (80.3) | 29 (80.6) | 151 (80.3) | 1.00 |

| Definitive/Adjuvant Radiation | ||||

| Yes | 39 (25.7) | 13 (36.1) | 52 (27.7) | |

| No | 113 (74.3) | 23 (63.9) | 136 (72.3) | .22 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 121 (79.6) | 24 (66.7) | 145 (77.1) | |

| No | 31 (20.4) | 12 (33.3) | 43 (22.9) | .12 |

| Immunotherapy | ||||

| Primary immunotherapy | ||||

| Nivolumab | 120 (78.9) | 34 (94.4) | 154(81.9) | |

| Pembrolizumab | 22 (14.5) | 1 (2.8) | 23 (12.2) | |

| Durvalumab | 10 (6.6) | 1 (2.8) | 11 (5.9) | .10 |

| Single agent versus combination | ||||

| Monotherapy | 105 (69.1) | 22 (61.1) | 127 (67.6) | |

| Combination | 47 (30.9) | 14 (38.9) | 61 (32.4) | .43 |

| Secondary agent | N = 47 | N = 14 | N = 61 | |

| Anti—CTLA-4 | 12 (25.5) | 6 (42.9) | 18 (29.5) | |

| Chemotherapy | 4 (8.5) | 2 (14.3) | 6 (9.8) | |

| Other investigational therapy | 31 (70.0) | 6 (42.9) | 37 (60.7) | .25 |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CTLA-4 = cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 receptor; IR = immune related; NSCLC NOS = non–small-cell lung cancer not otherwise specified.

Prior treatment at time of initial diagnosis included surgery, definitive or adjuvant radiation to chest, and first-line chemotherapy, concurrent chemoradiation or adjuvant chemotherapy.

All subjects consented to participate (IRB00087582).

Radiation Treatment.

Among the entire cohort, 70% (132/188) of patients received at least one course of any RT, 53% (100/188) received chest RT, and 14% (26/188) received more than one course of chest RT (Table 2; Supplemental Figure 1 in the online version). Among the 100 patients who received chest RT, 70% (n = 70) received curative-intent chest RT and 30% (n = 30) received palliative-intent chest RT.

Table 2.

Radiotherapy Characteristics and Associations With IR Pneumonitis

| Characteristic | No IR Pneumonitis | IR Pneumonitis | All Patients | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT Characteristic | N = 152 (81) | N = 36 (19) | N = 188 | |

| Any RT | ||||

| Yes | 111 (73) | 21 (58.3) | 132 (70.2) | |

| No | 41 (27) | 15 (41.7) | 56 (29.8) | .11 |

| RT Within 1 Year of Anti—PD-1 /PD-L1 Therapy | ||||

| Yes | 88 (57.9) | 16 (44.4) | 104 (55.3) | |

| No | 64 (42.1) | 20 (55.6) | 84 (44.7) | .19 |

| Any Chest RT | ||||

| Yes | 81 (53.3) | 19 (52.8) | 100 (53.2) | |

| No | 71 (46.7) | 17 (47.2) | 88 (46.8) | 1.00 |

| > 1 Course Chest RT | ||||

| Yes | 21 (13.8) | 5 (13.9) | 26 (13.8) | |

| No | 131 (86.2) | 31 (86.1) | 162 (86.2) | 1.00 |

| Chest RT Within 1 Year of/anti—PD-1 /PD-L1 Therapy | ||||

| Yes | 56 (36.8) | 12(33.3) | 68 (36.2) | |

| No | 96 (63.2) | 24 (66.7) | 120 (63.8) | .85 |

| > 1 Course Chest RT Within 1 Year of Anti—PD-1 /PD-L1 Therapy | ||||

| Yes | 8 (5.3) | 2 (5.6) | 10 (5.3) | |

| No | 144 (94.7) | 34 (94.4) | 178 (94.7) | 1.00 |

| Chest-RT Characteristic | N = 81 (81) | N = 19 (19) | N = 100 | |

| Chest RT indication | ||||

| Palliative | 28 (34.6) | 2(10.5) | 30 (30) | |

| Curative intent | 53 (65.4) | 17 (89.5) | 70 (70) | .051 |

| Chest RT Dose (Gy) | ||||

| Available | 65 | 19 | 84 | |

| Median | 60 | 60 | 60 | |

| Range | 20–70 | 20–66.6 | 20–70 | .46 |

| Radiation Dosimetric Parameter | N = 43 | N = 12 | N = 53 | |

| Mean lung dose (Gy) | 12.46 (0.6–20.8) | 12.4 (1.4–19.8) | 12.4 (0.6–20.8) | .72 |

| Lung V20a | 23 (1–36) | 20.5 (0–34) | 22 (0–36) | .79 |

| Any SBRT Chest RT | ||||

| Yes | 7 (8.6) | 2 (10.5) | 9(9) | |

| No | 74 (91.4) | 17 (89.5) | 91 (91) | .68 |

| Any IMRT/VMAT Chest RT | ||||

| Yes | 36 (44.4) | 10 (52.6) | 46 (46) | |

| No | 45 (55.6) | 9 (47.4) | 54 (54) | .61 |

| Any 2-D/3-D Conformai Chest RT | ||||

| Yes | 23 (28.4) | 6(31.6) | 29 (29) | |

| No | 58 (71.6) | 13 (68.4) | 71 (71) | .78 |

| Curative-Intent Chest-RT Characteristic | N = 53 (76) | N = 17 (24) | N = 70 | |

| Curative intent Chest RT Before Anti—PD-1 /PD-L1 | ||||

| Yes | 49 (92.5) | 16 (94.1) | 65 (92.9) | |

| No | 4(7.5) | 1 (5.9) | 5(7.1) | 1.00 |

| RT Dosimetric Parameter | N = 30 | N = 10 | N = 38 | |

| Mean lung dose (Gy) | 15.1 (2.8–20.8) | 12.8 (8.7–19.8) | 14.8 (2.8–20.8) | .62 |

| Lung V20 | 25.5 (2–36) | 22 (14–34) | 24 (2–36) | .78 |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: 2-D = 2-dimensional; 3-D = 3-dimensional; curative intent = definitive, adjuvant, or consolidative radiation; IMRT = intensity-modulated radiotherapy; IR = immune related; PD-I = programmed cell death I receptor; PD-L1 = programmed cell death ligand 1; RT = radiotherapy; SBRT = stereotactic body radiotherapy; VMAT = volumetric modulated arc therapy; V20 = percentage lung volume receiving 20 Gy.

Three patients in no-IR pneumonitis group had mean lung dose available, but did not have V20 available.

Chest Radiation and IR Pneumonitis

Of the 36 patients who developed IR pneumonitis, 53% (19/36) had received any prior chest RT– of which, patients who received chest RT with curative intent (17/19, 89%) more likely to develop IR pneumonitis compared to those who received palliative-intent chest RT (2/19, 11%; P = .051). Correspondingly, among all 100 patients who received ICI therapy and who were treated with chest RT, IR pneumonitis was more common in patients treated with curative-intent chest RT (17/70, 24%) compared to those treated with palliative-intent chest-RT (2/30, 7%) (P = .051).

Dose details were available for 84% (84/100) of patients who received chest RT. The median highest dose of chest RT was 30 (range, 20–30) Gy in the palliative-intent chest RT group and 60.5 (range, unknown to 70) Gy in the curative-intent group (Table 2, Supplemental Figure 1 in the online version). Dosimetric details were available for 53% (53/100) of patients. There were no significant differences between available mean lung dose and percentage lung volume receiving 20 Gy in the no–IR pneumonitis and IR pneumonitis group (P > .05; Table 2). Data regarding chest RT technique were available in 68% (68/100) of patients. There were no significant associations between chest-RT technique and development of IR pneumonitis (P > .05, Table 2).

Timing of Chest RT and IR Pneumonitis

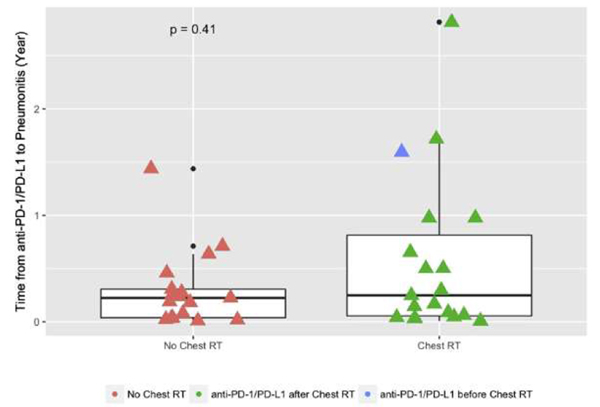

In this cohort of patients who developed IR pneumonitis, patients received chest RT before or after anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy (Figure 1). The time from receipt of ICIs to development of IR pneumonitis in relation to chest RT was examined. Of the 36 patients who developed IR pneumonitis, the median time from first anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy to onset of IR pneumonitis was not statistically different among those patients who received chest RT compared to those patients who did not receive chest RT (P = .41; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship of Immune-Related Pneumonitis Timing and Chest Radiation

Scatterplot showing time from first dose of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy to development of immune-related pneumonitis, stratified by receipt of chest radiation. median Ttme interval and interquartile ranges are shown

Abbreviations: PD-1 = programmed cell death receptor 1; PD-L1 = programmed death ligand 1.

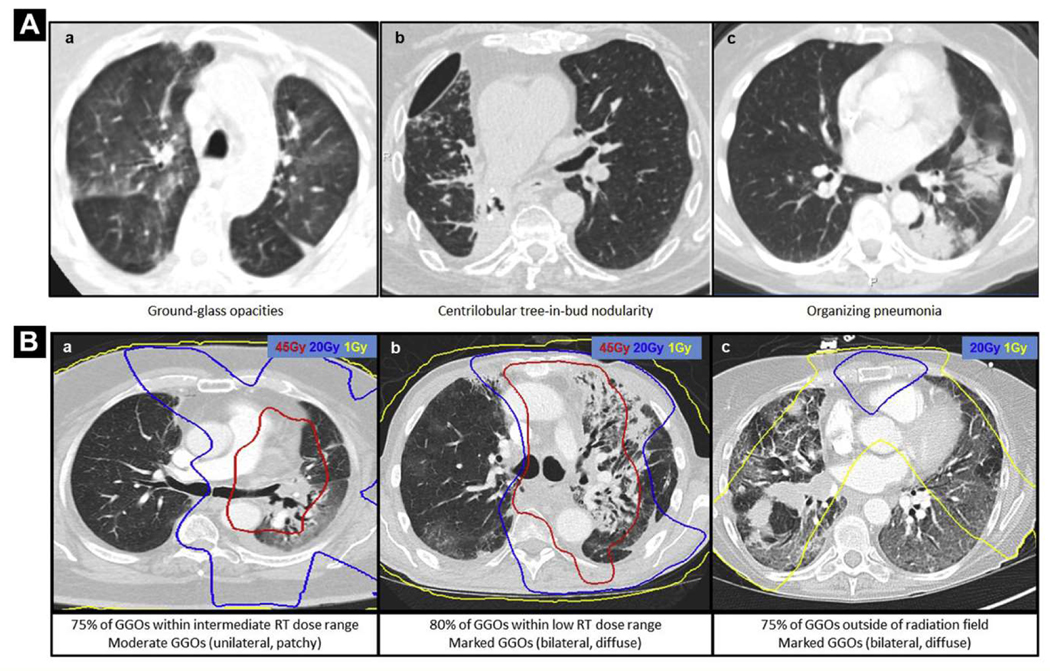

Radiologic Features in Patients With IR Pneumonitis and Prior Irradiated Lung

Of the 19 IR pneumonitis patients who had prior chest RT treated at our institution, electronic RT plans were available for 13 patients. Table 3 outlines the descriptive radiologic findings of IR pneumonitis in relation to prior chest RT details. Two (15%) of 13 patients had palliative-intent chest RT (range, 20–30 Gy), and the remaining 11 (85%) had curative-intent chest RT (range, 52.5–66 Gy). Overall, the predominant IR pneumonitis feature on chest CT was GGOs in 10 patients (77%), organizing pneumonia in 2 (15%), and centrilobular tree-in-bud nodularity in 1 (8%). A representative example of each of these pneumonitis features is depicted in Figure 2A. The majority of GGOs were located outside the high RT dose regions, either within the low-dose range (n = 5, 38%; > 1 Gy and < 20 Gy) or outside the RT fall-off dose region (n = 7, 54%; < 1 Gy). In 1 patient (8%), the majority of the GGOs were within the intermediate-dose range (> 20 Gy and < 45 Gy). Corresponding examples of chest RT plans fused over diagnostic IR pneumonitis CT scans are depicted in Figure 2B.

Table 3.

IR Pneumonitis and IR Pneumonitis Radiographic Features in Relation to RT Fields

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| IR Pneumonitis (CTCAE grade) | n (%) |

| All grades | 36 (100) |

| Grade 2 | 14 (38.9) |

| Grade 3 | 14 (38.9) |

| Grade 4 | 2 (5.6) |

| Grade 5 | 5 (13.9) |

| Unknown | 1 (2.8) |

| IR Pneumonitis Radiographic Features With Overlaid Chest RT Plans | N = 13 |

| Chest RT Indication | |

| Palliative intent (20–30 Gy) | 2(15) |

| Curative intent (52.5–66 Gy) | 11 (85) |

| Predominant IR Pneumonitis Feature | |

| Moderate to marked GGO | 7(54) |

| Minimal to mild GGO | 3 (23) |

| Organizing pneumonia | 2(15) |

| Centrilobular tree-in-bud nodularity | 1 (8) |

| Predominant Location of IR Pneumonitis Feature in Relation to Chest-RT Dose Regionsa | |

| High-dose RT | 0 |

| Intermediate-dose RT | 1 (8) |

| Low-dose RT | 5 (38) |

| Outside RT dose fall-off region | 7(58) |

High dose, > 45 Gy; intermediate dose, > 20 Gy and < 45 Gy; low dose, < 20 Gy; outside RT fall-off region, < 1 Gy.

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography; CTCAE = Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0; Curative intent = definitive, adjuvant, or consolidative radiation; GGO = ground-glass opacity; IR = immune related; RT = radiotherapy.

One patient with minimal GGO pattern of IR pneumonitis was not categorized in relation to radiation dose zones, given minimal radiographic extent. One patient had GGOs equally distributed between low RT dose region and beyond RT dose fall-off region.

Figure 2.

Representative Immune-Related Pneumonitis Diagnostic Scans With Overlaid Prior Chest Radiation

(A) Representative axial images of diagnostic CT scans of 3 patients who developed immune-related pneumonitis showing features of (a) ground-glass opacities (GG0s), (b) centrilobular tree-in bud nodularity, and (c) organizing pneumonia. (B) Respective RT dose zones are overlaid on top of chest CT images in 3 patients who developed immune-related pneumonitis showing GGOs. these examples show where the majority of immune-pneumonitis radiologic features of GGOs localize within (a) the intermediate range of chest-radiation doses (> 20 Gy and < 45 Gy), (b) the low range of chest-radiation doses (> 1 Gy and < 25 Gy), and (c) outside the radiation field (< 1 Gy)

Abbreviation: CT = computed tomography.

There were 9 patients (69%) with radiographic patterns of fibrosis. In all cases, the majority of the fibroses fell within the high RT dose range (> 45 Gy).

Survival

For the entire cohort, the median OS was 14.6 months (95% CI, 10.6–21.8). There was no difference in OS when stratified by receipt of chest RT (P > .05) at all landmark analysis time points (0, 3, 9, and 12 months). We previously described the impact of IR pneumonitis on survival in these patients via multistate Markov modeling and its associations with non–RT-related clinical factors.16

Discussion

Previous reports on this large series of patients with advanced NSCLC who developed IR pneumonitis after receipt of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy have focused on non–radiation-related clinical factors affecting the incidence risk of IR pneumonitis and OS among those who develop IR pneumonitis using multistate modeling. In this study, we focused specifically on identifying associations between the development of IR pneumonitis and past receipt of radiation, specifically chest RT, parameters. Importantly, we did not identify any specific RT-related treatment parameter (such as technique, timing, courses, prior chest-RT dosimetric parameter) that was associated with the development of IR pneumonitis. However, in patients treated with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 who developed IR pneumonitis and who received chest RT (n = 19), we identified a numeric difference between receipt of chest RT with curative-intent than with palliative intent (89% vs. 11%) that approached statistical significance (P = .051). Correspondingly, in patients who were treated with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 and who received any prior chest RT (n = 100), IR pneumonitis was numerically more common in patients treated with curative-intent compared to palliative-intent (24% vs. 7%) chest RT (P = .051). This study highlights for clinicians the potential increased risk for IR pneumonitis in patients who have received prior-curative intent rather than palliative-intent chest RT.

The ability to stratify the risk of IR pneumonitis in the context of prior chest RT is of particular relevance in light of the recent publication of the phase III PACIFIC trial. In this trial, patients with stage III NSCLC received 1 year of maintenance durvalumab within 6 weeks after completion of definitive chemoradiation, with any grade and grade 3+ pneumonitis occurring in 33.9% (161/475) and 3.4% (16/475) of durvalumab-treated patients, respectively.22 Accordingly, the rates of pneumonitis in this US Food and Drug Administration–approved indication were higher than in previously reported anti–PD-1/PD-L1 trials in advanced NSCLC. Smaller series evaluating pulmonary IR adverse events and their relationship to chest-RT have been reported. In a retrospective series of 164 lung cancer patients with any grade IR pneumonitis, the incidence of IR pneumonitis was marginally higher in those who received prior chest RT versus those who did not (6/73, 8.2%, vs. 5/91, 5.5%, P=.54).23 Our results build on this observation in that we identify that specifically curative-intent chest RT may increase the risk of any grade IR pneumonitis. Unlike prior retrospective studies that have focused principally on associations with clinical benefit of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy and prior RT, our study explored whether specific RT parameters may influence the development of IR pneumonitis. Importantly, we did not observe any significant associations between the RT technique (stereotactic body RT, intensity-modulated RT) or the timing of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy and the development of IR pneumonitis.

Furthermore, the ability to identify IR pneumonitis and distinguish it from RT changes is an important clinical skill. In this study, we spatially related the radiographic features of IR pneumonitis to the regions of previously irradiated lung. We identified that for those who developed IR pneumonitis, the predominant radiographic feature of GGOs was found within lung volumes that received intermediate and low doses of RT rather than areas of higher RT dose delivery, where fibrosis predominated. Although the numbers of patients and the availability of appropriate scans in this study were small, our data suggest that this spatially distinct description of radiographic IR pneumonitis features may assist thoracic oncologists in their ability to differentiate between IR pneumonitis and RT-related fibrotic changes in patients treated with prior chest RT.

Our intent was to evaluate the association between various radiation parameters and the development of IR pneumonitis. A secondary goal was to describe the spatial relationship between radiologic findings of IR pneumonitis and regions of the lung that received radiation. As more patients are treated with both definitive chest RT and immunotherapy following the demonstrated survival benefit of adjuvant durvalumab after definitive chest RT, the ability of clinicians to distinguish RT pneumonitis from IR pneumonitis becomes exceedingly important. Of note in the Pacific trial, their definition of pneumonitis was not clearly attributed to an underlying cause (IR, RT, or combined pneumonitis). Although the scope of our study was not to distinguish between IR and RT pneumonitis, as patients with both IR pneumonitis and RT pneumonitis were unavailable for comparison, this remains an area that requires further investigation. Future studies are needed for in-depth and direct comparisons of the radiographic features among patients who develop IR pneumonitis alone, RT pneumonitis alone, and both IR and RT pneumonitis.

While this is to our knowledge the largest analysis in the literature of patients with IR pneumonitis aimed at exploring relationships between chest RT and IR pneumonitis in NSCLC, we are limited by the small sample size, the relatively uncommon event of IR pneumonitis, and the retrospective nature of our study. In addition, although we extensively reviewed RT history and parameters for each patient, the analysis was limited to those in whom RT details were available. Finally, it will be important in future studies to assess other clinical data that may affect IR pneumonitis risk, such as receipt of type of prior chemotherapy or targeted agents, and toxicities associated with prior therapies.

As the indications for ICIs expands in stage III and IV NSCLC, practicing oncologists will need to risk-stratify patients for the development of IR pneumonitis as well as identify clinical parameters that help to differentiate this phenomenon from other diagnoses, especially RT pneumonitis. We previously reported that IR pneumonitis incidence (19%) was higher than rates reported in published clinical trials. In this series, we found that there is potentially a higher risk of this phenomenon in patients treated with curative-intent chest RT, but the timing and potentially the technique of chest RT is unlikely to be a relevant risk factor. A better understanding of the risks of chest RT will require a secondary analysis of chest RT plans from the phase III PACIFIC trial. It will also require the development of well-curated registries of multidisciplinary patient-specific data–data that include RT details and toxicities, pneumonitis CT images, lung functional data, and pulmonary lavage samples–to comprehensively identify risk factors for IR pneumonitis in the context of prior chest RT.

Clinical Practice Points

The reported incidence of IR pneumonitis following anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy ranges from 1% to 10%.

Our study explored whether specific RT parameters may influence the development of IR pneumonitis in patients with advanced NSCLC who received anti–PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibition at a single institution.

No RT parameter (technique, timing, courses, prior chest RT dosimetric parameter) was statistically significantly associated with the development of IR pneumonitis. However, we identified on subset analysis of patients who developed IR pneumonitis and received chest radiation (chest RT), patients who developed IR pneumonitis were numerically more likely to have received chest RT with curative intent than with palliative intent (89% vs. 11%), that approached statistical significance.

We identified for those who developed IR pneumonitis and who had overlaid electronic chest RT plans on diagnostic chest imaging that the predominant radiographic feature of GGOs was found spatially within lung volumes that received intermediate and low doses of RT, rather than areas of higher RT dose delivery, where features of fibrosis predominated.

This study highlights for clinicians the potential for higher risk for IR pneumonitis in patients who have received prior curative-intent, rather than palliative-intent, chest RT.

This study’s spatial description of IR pneumonitis features in relation to chest RT dose regions may assist thoracic oncologists in their ability to differentiate between IR pneumonitis and RT-related fibrotic changes in patients treated with prior chest RT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Lai Wei for fusing restored chest radiation plans onto diagnostic CT scans.

Disclosure

J.R.B. reports other from BMS (uncompensated), grants from BMS, grants from AstraZeneca/MedImmune, personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Genentech, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from Lilly, and personal fees from Amgen outside the submitted work. D.S.E. reports personal fees from BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from Eli Lilly & Co, and personal fees from Genentech, personal fees from Guardant Health Inc outside the submitted work. J.L.F. reports other from AstraZeneca, other from Takeda, and other from Merck, outside the submitted work. P.M.F. reports grants from Bristol Myers-Squibb, grants from AstraZeneca, grants from Kyowa-Kirin, grants from Novartis, other from Bristol Myers-Squibb, other from AstraZeneca, other from Novartis, other from Merck, other from EMD, other from AbbVie, other from Inivata, outside the submitted work. C.L.H. reports other from AbbVie, other from Bristol Myers Squibb, other from Genentech, grants and other from GlaxoSmithKline, grants from Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. C.H. reports grants from National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study. R.J.K. reports grants from Bristol Myers-Squibb, grants from AstraZeneca, grants from Eli Lily, other from Bristol Myers-Squibb, other from Eli Lilly, other from Astellas, other from EMD Serono, other from Novartis, other from Gritstone Oncology, other from Cardinal Health, outside the submitted work. B.L. has grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Celgene, other from Merck, Celgene, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Takeda and Eli Lilly, outside the submitted work; and advisory/consulting for Merck, Celgene, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Takeda, and Eli Lilly K.A.M. reports personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Compugen, outside the submitted work. J.N. reports grants from Merck, grants from AstraZeneca, other from Bristol Myers Squibb, other from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. K.R.V. reports grants from Lung Cancer Research Foundation, grants from Radiation Oncology Institute, personal fees from ASCO Advantage, outside the submitted work. The other authors have stated that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental Data

Supplemental figure accompanying this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2019.02.018.

References

- 1.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-LI–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:1823–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-LI –positive, advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387:1540–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1627–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti–PD-1 and anti P’D-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol 2015; 26:2375–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Disayabutr S, Calfee CS, Collard HR, et al. Interstitial lung diseases in the hospitalized patient. BMC Med 2015; 13:245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishino M, Sholl LM, Hodi FS, et al. Anti–PD-1–related pneumonitis during cancer immunotherapy. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:288–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-l antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2443–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delaunay M, Cadranel J, Lusque A, et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors associated with interstitial lung disease in cancer patients. Eur Respir J 2017; 50:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishino M, Ramaiya NH, Awad MM, et al. PD-I inhibitor–related pneumonitis in advanced cancer patients: radiographic patterns and clinical course. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22:6051–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, et al. Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-I/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35:709–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishino M, Giobbie-Hurder A, Hatabu H, et al. Incidence of programmed cell death 1 inhibitor-related pneumonitis in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2:1607–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, et al. Irradiation and anti–PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 687–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golden EB, Demaria S, Schiff PB, et al. An abscopal response to radiation and ipilimumab in a patient with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2013; 1:365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaverdian N, Lisberg AE, Bornazyan K, et al. Previous radiotherapy and the clinical activity and toxicity of pembrolizumab in the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer: a secondary analysis of the KEYNOTE-001 phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18:895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suresh K, Voong KR, Shankar B, et al. Pneumonitis in non–small cell lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint immunotherapy: incidence and risk factors. J Thorac Oncol 2018; 13:1930–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suresh K, Psoter KJ, Voong KR, et al. Impact of checkpoint inhibitor pneumonitis on survival in non–small cell lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint immunotherapy. J Thorac Oncol 2018; 13:1930–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phernambucq EC, Palma DA, Vincent A, et al. Time and dose-related changes radiological lung density after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2011; 74:451–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernchou U, Schytte T, Bertelsen A, et al. Time evolution of regional CT density changes in normal lung after IMRT for NSCLC. Radiother Oncol 2013; 109:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veiga C, Landau D, McClelland JR, et al. Long term radiological features of radiation-induced lung damage. Radiother Oncol 2018; 126:300–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Partridge M, Ramos M, Sardaro A, et al. Dose escalation for non–small cell lung cancer: analysis and modelling of published literature. Radiother Oncol 2011; 99:6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senthi S, Haasbeek CJ, Slotrnan BJ, et al. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for central lung turnours: a systematic review. Radiother Oncol 2013; 106:276–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:1919–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang WL, Niernierko A, Hwang KL et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic lung cancer treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and thoracic radiotherapy. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4253–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.