Abstract

Background:

The use of ventricular assist devices (VADs) as a bridge-to-transplant in patients with single-ventricle physiology post–stage one palliation has been associated with poor outcomes. We describe our center’s successful experience in the use of paracorporeal pulsatile VADs in the palliation of high-risk single ventricle physiology before or after the first stage of palliation with an impetus on prepalliation implant.

Methods:

This is a single-center retrospective review of univentricular patients implanted with the Berlin Heart EXCOR VAD. Our center’s approach includes early implantation of the Berlin Heart EXCOR with common atrial cannulation, a cardiac index between 3.5 and 5 L/min/m2, and a bivalirudin-based anticoagulation regimen. Patient-related data were collected postimplant at week 1 and months 1, 2, and 3. Post-transplant data, including neurological outcomes, were collected.

Results:

Nine patients were supported. Survival to discharge post-transplant was 83% (5/6) in patients bridged-to-transplant and 33% (1/3) in patients bridged-to-decision. Six patients had no previous palliation. Median hospital stay before implantation was 111 days for nonsurvivors versus 20 days for survivors. The need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in nonsurvivors versus survivors was 1 in 3 versus 1 in 6 and 2 in 3 versus 1 in 6, respectively. There were no major central nervous system complications except for 1 significant hemorrhagic event. The pediatric overall performance category score on follow-up was normal to mild disability in 83% of survivors. Limitations include hemolysis and intermittent periods of infection and/or inflammation.

Conclusions:

The use of pulsatile paracorporeal VADs is a feasible option as a bridge-to-transplant in the peri–stage one high-risk single ventricle.

Keywords: pulsatile paracorporeal VAD, failing high-risk peri–stage-one single ventricle physiology, mechanical circulatory support, heart transplantation

CENTRAL MESSAGE

Pulsatile paracorporeal VAD as a bridge-to-transplant is a feasible therapy for patients with high-risk single ventricle physiology before or after the first stage of palliation.

Despite improved outcomes in single-ventricle patients, before or after stage one palliation, there is a subset of patients with unfavorable anatomical features or heart failure physiology that precludes palliation along the classical surgical route or do poorly after the same. A subset of these patients remains at risk for early death, with heart transplant being the only respite. The use of the pulsatile EXCOR device (Berlin Heart, Berlin, Germany) to support patients with initial palliation of single-ventricle circulation has historically been associated with high mortality.1 In 2009, Pearce and colleagues2 described the successful use of the Berlin Heart EXCOR as a bridge-to-transplant in a 15-month-old boy with double-outlet right ventricle and hypoplastic left ventricle postpulmonary artery banding. Despite this initial success, Weinstein and colleagues1 in 2014 reported a 10% survival rate to transplant for single-ventricle patients post–stage one palliation supported by the Berlin Heart EXCOR (Berlin registry from 2007 to 2012). Also, the use of Berlin Heart EXCOR in patients less than 5 kg with congenital heart disease rendered poor outcomes, leading to centers restricting the use of the Berlin Heart EXCOR in this cohort.3

Gazit and colleagues4 used a continuous-flow device in 7 single-ventricle patients post–stage one palliation who were successfully bridged-to-transplant. This experience followed by other case reports allowed more centers to use the continuous-flow devices, which were once used as an option for short-term support in the peri–stage one patient. After successfully bridging multiple Berlin Heart EXCOR 10-mL pumps in patients with biventricular physiology, our center explored implanting the 10-mL Berlin Heart EXCOR in a neonate with heart failure in the context of single-ventricle physiology before palliation.5 The hybrid-pulsatile ventricular assist device (VAD) in a patient with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) approach was reported by our center in 2018.6 Our protocol was modified to also choose pre-emptive implants for patients with unfavorable anatomy and risk of cardiac compromise before palliation. We present our series of 9 patients with peri–stage one single-ventricle physiology supported by a pulsatile VAD as a bridge-to-transplant in this study.

METHODS

This study was approved by the institutional review board as a retrospective chart review with a full waiver of informed consent. Data were compiled from the electronic medical record and were collected and analyzed within the Research Electronic Data Capture. This is a descriptive study; data are presented as percentages and median intervals. Only patients with single-ventricle physiology pre- or post–stage one palliation were included in this study. The VAD used on these patients was limited to the Berlin Heart EXCOR. Survival was based on survival to discharge post-transplant.

Demographic data were collected and included sex, weight, height, and body surface area (BSA) at implantation of the VAD. Data collected also included the type of single-ventricle physiology, anatomical variations, blood type, need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and/or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) before VAD implantation. Source of parallel blood supply (either to the systemic or pulmonary circulation) and pump size were also collected.

Other data collected included inflammatory markers, volume/type of transfusions, and end-organ function. VAD-related data were collected at 1 week and months 1, 2, and 3 after VAD implantation. Neurologic outcomes were evaluated post-transplant and were based on pediatric or neurology visits in the patients’ electronic medical record. Creatinine clearance was calculated using the Schwartz formula.

University of Florida VAD Protocol

During the discussion for surgical palliation, a decision for a device implant is made. Indications to implant a VAD include signs of ischemia from a ventricle-dependent coronary physiology or unfavorable anatomy with large coronary sinusoids, patients with poor ventricular or atrioventricular valve function needing persistent mechanical ventilation and inotropic support with associated inability to feed or rehabilitate, and/or worsening end-organ function. Criteria for implant postpalliation include the latter indications. The patients who had advanced end-organ injuries that traditionally would have deemed VAD support as futile are categorized as a bridge-to-decision.

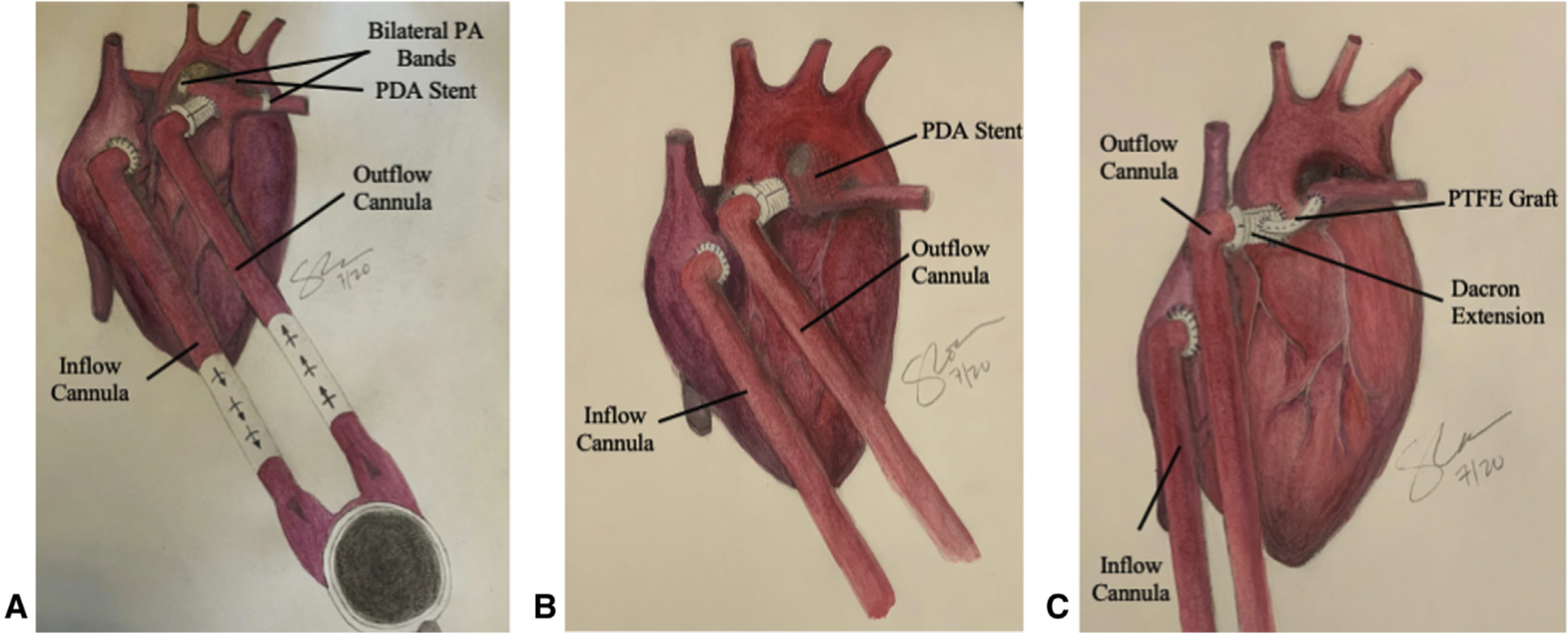

Following the decision to implant the VAD, the source of parallel blood circulation (either to the systemic or pulmonary circulation) is discussed (Figure 1). The stented ductus in the context of hybrid palliation is preferred for the non-palliated HLHS or the isolated ductal stent in the non-palliated pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PA/IVS). In patients with either HLHS postpalliation or the inability to stent a tortuous ductus for PA/IVS, a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) graft (Y configuration) is attached to the 8-mm Dacron extension of the outflow graft to the aorta to provide pulmonary blood flow. The take-off from the Dacron graft is an angled take-off with a smooth course (not 90°) laid along a path with the least likelihood of compression. The rationale behind this is a more secure source of pulmonary blood flow and one that is more central, allowing for equal growth of both PAs. In a patient post-Norwood with a Sano shunt, the proximal part of the Sano shunt attached to the right ventricle is clamped and tied off. The remaining length of the Sano shunt was attached via a PTFE graft to the Dacron extension of the outflow cannula to the neo-aorta forming the same Y configuration. Other surgical options are a modified Blalock–Thomas–Taussig shunt or a central shunt for pulmonary blood flow and will be the source of pulmonary blood flow in the case of a palliated PA/IVS. There was 1 patient in our cohort with a BT shunt post-Norwood who was our earliest patient and needed support for only 12 days. Our surgical team prefers the Y shunt due to the concern for thrombosis of the BT/central shunt in the context of a longer duration of support.

FIGURE 1.

Depictions of ventricular assist device support in the single ventricle. A, Ventricular assist device with Hybrid palliation. PDA stent and bilateral PA bands. Inflow cannula to the right atrium and outflow cannula to the PA. B, Ventricular assist device with PDA stent. Inflow cannula to the right atrium and outflow cannula to the ascending aorta. C, Ventricular assist device with a PTFE graft connecting the outflow cannula to the pulmonary artery. Inflow cannula to the right atrium and outflow cannula to the ascending aorta. PA, Pulmonary artery; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PTFE, polytetrafluoroethylene.

The immediate postimplant cardiac index (CI) is set at 3.5 to 4.0 L/min/m2 and titrated to filling pressures and hemodynamic requirements of the patient. The patients’ myocardium continues to contribute a part of the total CI. The goal is to achieve adequate mixed venous saturations. Following the implant, the pump rate is increased every 4 weeks to keep the CI consistent for growth. Our goal range is 3.5 to 5.0 L/min/m2.

If there is severe end-organ injury at implant, a greater CI is targeted (4.0 to 5.0 L/min/m2). An increase of CI is also done in scenarios suggestive of inadequate decompression like persistent pleural effusions in the context of maximum diuresis or intolerance of feeds. In rare instances, the CI was increased to increase pulmonary blood flow when their source of pulmonary blood flow became limited as the patient continued to grow (usually following prolonged support).

Diuresis and permissive hypertension with a goal systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg are the mainstays of initial therapy. Bivalirudin, our primary method of anticoagulation since 2016, is started 24 hours after implant and monitored with partial thromboplastin time and thromboelastography. Goals for the first 2–3 days can be lower based on patient hemostasis. With our growing experience, the threshold for transfusions in these patients has changed to a lower threshold following the first 2 weeks postimplant. The goal for hematocrit in the first 2 weeks is 35–45 mg/dL followed by a liberalized hematocrit goal of 25–30 mg/dL, according to markers of poor oxygen delivery or impaired oxygenation after the first 2 weeks. All our patients are on micronutrient supplementation with iron, folic acid, and erythropoietin.

Close observation for markers of infection is maintained throughout VAD support. Antibiotic coverage is initiated with fever or clinical signs of sepsis until there are results of cultures and inflammatory markers. Following the results and based on the clinical course, the duration of therapy is decided. If the administration of 3 or more courses of antibiotics is needed with intervals of less than 1 week between each of these courses, then patients were prescribed cephalosporins (cefazolin or cefepime, according to previous sensitivities) until transplant. Steroid pulses with methylprednisolone are done when deposits increase on the VAD and fibrinogen levels are greater than 500 mg/dL or high sensitivity-C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) is >70 mg/L, similar to Byrnes and colleagues7 Another reason for a steroid course would be increasing bivalirudin infusion dosages to achieve therapeutic partial thromboplastin time when previously stable. This scenario is usually associated with signs of increased inflammation, even though hs-CRP and fibrinogen levels are not at thresholds mentioned previously.

Patients 4 and 8 had 25-mL pumps. The goal was to target an initial CI of 3.5 to 4 L/min/m2 with an ability for titrations with growth. Our recommendations assuming a maximum Berlin Heart EXCOR rate of 115 are <5 kg, BSA <0.28: 10-mL pump, 5–8 kg, BSA 0.28–0.40: 15-mL pump, and >8 kg, BSA >0.40: 25-mL pump.

From 2016 to 2019, we completed Norwood palliation for 32 patients with HLHS with 1 death postoperatively, hybrid procedures without a VAD in 2 patients, prostaglandin infusions to primary transplants in 3, and hybrid palliations with a VAD in 5 patients. As for patients with PA/IVS data, we completed primary palliation in 2 patients, with 4 on prostaglandin E to primary transplant due to unfavorable anatomy from sinusoids. Two patients were implanted with a VAD for coronary ischemia.

RESULTS

Patient and VAD Characteristics

Nine patients met inclusion criteria, including 3patients who were post–stage-one palliation (Tables 1–3 and Figure 2). The total survival in the cohort was 66%. The survival to discharge post-transplant was 83% (5/6) in patients bridged-to-transplant and 33% (1/3) in patients bridged-to-decision. Two-thirds of nonsurvivors needed CPR before implantation (compared with 1/6 in survivors). At implant and explant, the median CI was 3.6 and 4.4 L/min/m2, respectively. Due to our small sample size (6 survivors vs 3 nonsurvivors), statistical analysis was not done.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics among survivors and nonsurvivors

| Variables | Survivors (6) | Nonsurvivors (3) | Total (9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males, n (%) | 3 (50) | 2 (67) | 5 (56) |

| Weight, kg, range | 2.4–10.2 | 3.3–8.9 | 2.4–10.2 |

| Median [IQR] | 4 [4, 6] | 4 [3, 5] | 4 [3, 5] |

| BSA, m2, range | 0.20–0.42 | 0.20–0.41 | 0.20–0.42 |

| Median [IQR] | 0.22 [0.21, 0.23] | 0.21 [0.21, 0.31] | 0.22 [0.20, 0.23] |

| Blood type O, n (%) | 5 (83) | 2 (67) | 7 (78) |

| ECMO pre-VAD, n (%) | 1 (17) | 1 (33) | 2 (22) |

| CPR pre-VAD, n (%) | 1 (17) | 2 (67) | 3 (33) |

| LOS, median [IQR] | 151 [111, 201] | 160 [114, 205] | 160 [109, 207] |

| LOV, median [IQR] | 64 [25, 138] | 56 [33, 97] | 64 [12, 138] |

| LOAV, median [IQR] | 20 [15, 23] | 111 [62, 131] | 20 [13, 66] |

| LOMV, median [IQR] | 4.5 [4, 7] | 10 [9, 69] | 7 [4, 10] |

IQR, Interquartile range; BSA, body surface area; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; VAD, ventricular assist device; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; LOS, length of stay; LOV, length of VAD support; LOAV, length of admission to VAD implantation; LOMV, length of mechanical ventilation after implantation.

TABLE 3.

CI at various stages postimplant in survivors and nonsurvivors

| Patient number | Inflow cannula, mm | Outflow cannula, mm | CI at implant, L/min/m2 | CI at explant, L/min/m2 | PV, mL | BSA at implant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivors | ||||||

| Patient 1 | 6 | 5 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 10 | 0.19 |

| Patient 2 | 6 | 6 | 3.2 | 4 | 10 | 0.22 |

| Patient 3 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3.2 | 10 | 0.22 |

| Patient 4 | 9 | 6 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 25 | 0.51 |

| Patient 5 | 6 | 6 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 10 | 0.28 |

| Patient 6 | 6 | 6 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 10 | 0.24 |

| Nonsurvivors | ||||||

| Patient 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5.3 | 10 | 0.21 |

| Patient 8 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 4.3 | 25 | 0.44 |

| Patient 9 | 6 | 6 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 10 | 0.23 |

CI, Cardiac index; PV, pump volume; BSA, body surface area.

FIGURE 2.

The cohort consisted of 9 patients with single-ventricle physiology. These patients were pre– or post–stage one palliation and were all supported by the Berlin Heart EXCOR. The results including hematologic values, end-organ function, and inflammation are summarized as well as the implications of the results. The 3 surgical procedures performed are depicted. VAD, Ventricular assist device; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PA, pulmonary artery; PTFE, polytetrafluoroethylene; BT, Blalock–Thomas–Taussig; WBC, white blood count; Hs-CRP, high sensitivity c-reactive protein; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase.

All our patients are infants except patients 4 and 8. Patient 4 was born with double inlet left ventricle with transposition of the great arteries and was lost to follow-up after neonatal palliation with pulmonary artery bands. The patient presented as a toddler with heart failure and severe mitral valve regurgitation. This patient had a brief CPR event postmitral valve repair at our institution and was implanted as bridge-to-transplant. Patient 8 had hybrid palliation in the neonatal period for HLHS and was referred to us at 13 months of age for a heart/lung transplant evaluation in the context of increased pulmonary vascular resistance. Following evaluation at our institution, the decision was made for a heart transplant only. This patient had a CPR event during a respiratory infection 3 months after admission. The patient was placed on ECMO via CPR and then placed on a VAD due to nonrecovery of his cardiac function on ECMO.

Hemodynamic Therapy and Supportive Care

Vasodilator medications were weaned by the end of the first week and in most patients by the first 3 days (Table E1 and Figures E1 and E2). Only 3 patients in the cohort required long-term hypertensive medications and for a limited period in 2 of them. All patients required 2 diuretics during implant with the need for peritoneal dialysis in 1 patient who did not survive. All but 1 patient tolerated enteral nutrition postimplant with the incidence of blood in stools among both survivors and nonsurvivors (Table E2). Three patients were transitioned to elemental formula due to feeding intolerance and/or blood in stools.

Inflammation and Infection

White blood cells (WBC) remained consistently elevated among nonsurvivors through the second and third months of support in comparison with survivors (Figure 3). The percentage of lymphocytes trended lower in the nonsurvivors. Other inflammatory markers like hs-CRP showed an initial plateau, followed by an increase across our cohort. This was more evident in the nonsurvivors with the trend in hs-CRP twice the value among nonsurvivors throughout VAD support.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of inflammatory markers during VAD support. Inflammatory markers include hs-CRP, WBC, neutrophils, and lymphocytes and are compared among survivors and nonsurvivors. Survival is defined as survival to transplant postdischarge. The laboratory values were collected at week 1 and months 1, 2, and 3 status-postimplant. The hs-CRP, WBC, and neutrophils trended greater in nonsurvivors than survivors. Hs-CRP, High-sensitivity C-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cells.

Notable infectious events included a patient with persistent infections at the cannula site throughout VAD support. Despite negative blood cultures, the patient demonstrated intermittent fevers with increased WBC. The patient was transplanted without event. A different patient had recurrent infections while on the VAD, including cannula-site infections, tracheitis, and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Multiple pathogens were isolated including Achromobacter denitrificans, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia marcescens, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Unfortunately, this patient died from septic shock. A single episode of Escherichia coli urinary tract infection was also noted. Three patients received recurrent courses of antibiotics due to clinical sepsis, leading to the decision of prolonged prophylactic cephalosporin administration.

Hemolysis and Transfusion Requirements

There was a consistent need for packed red blood cell transfusions across the cohort (Table E3 and Figure 4). The total volume for transfusions was greater in the patients with the PTFE graft from the outflow cannula, with a consistent increase in markers of hemolysis with the PTFE graft compared with the patent ductus arteriosus stent.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of hematologic values during VAD support. Hematologic values include hematocrit, platelet count, PRBC transfusions, platelet transfusions, and FFP transfusions. The laboratory values and transfusions are compared among survivors and nonsurvivors. Survival is defined as survival to transplant postdischarge. The laboratory values were collected at week 1 and months 1, 2, and 3 status-postimplant. On average, the transfusions, hematocrit, and platelets trended greater in nonsurvivors than survivors. PRBC, Packed red blood cells; FFP, fresh frozen plasma.

The hematocrit for survivors trended slightly greater than in nonsurvivors despite lower transfusion rates, except for month 3 when one of the survivors had multiorgan dysfunction syndrome of unclear etiology from which the patient recovered. Comparatively, the survivor group needed platelet transfusions in week 1 but did not need fresh frozen plasma transfusions throughout VAD support.

End-Organ Function During VAD Support

Aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase were consistently greater in nonsurvivors than survivors except for month 3 (Figure 5). The survivors had consistent low total and direct bilirubin levels whereas the nonsurvivors had an increase in their bilirubin levels. Nonsurvivors’ blood urea nitrogen levels stayed above 20 mg/dL for the duration of the VAD whereas the survivors had levels above 20 mg/dL initially but fell below 20 mg/dL after a week on the VAD. Median creatinine clearance for survivors during VAD support was 84 mL/min per 1.73 m2 whereas nonsurvivors’ median creatinine clearance was 23 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The survivors’ creatinine clearance also generally improved after VAD implantation compared with the nonsurvivors. Nonsurvivors also spent more time on a mechanical ventilator after the implantation of the Berlin Heart EXCOR when compared with the survivors (median of 10 vs 4.5 days, respectively, Table 1).

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of end-organ function during VAD support. End-organ function values include blood urea nitrogen, AST, ALT, and creatinine. AST and ALT are used as markers of liver function whereas blood urea nitrogen and creatinine are used as markers of kidney function. These laboratory values are compared among survivors and nonsurvivors. Survival is defined as survival to transplant postdischarge. The laboratory values were collected at week 1 and months 1, 2, and 3 status-postimplant. End-organ dysfunction is more apparent in nonsurvivors than survivors. AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase.

Thrombosis and Central Nervous System (CNS) Events

Two patients postimplant were noted to have a minor CNS clinical change (Table E4). The electroencephalogram was normal in both cases. Computed tomography scans showed evidence of a small right frontal subdural collection and findings consistent with small bilateral subdural hematoma. Both patients had good neurological outcomes, having a pediatric overall performance category (POPC) score of 2 (mild disability). Patient 3 suffered a left thalamic hemorrhage, left frontal hemorrhage, and bilateral basoganglial hemorrhage 11 days after implant. This patient was anticoagulated with heparin. This patient had a POPC score of 3 (moderate disability) with cerebral palsy and seizure disorder. Patient 3, despite early features of cerebral palsy with a seizure disorder, was not categorized as a score of 4 because the infant at discharge interacted with family and had no limb, visual, or auditory deficits. Patient 4 with a POPC score of 3 had autistic features at baseline. Currently, this patient has normal muscle strength and bulk/overall muscle tone. Socially, the patient continues to have good eye contact, attends the appropriate grade level with accommodations, and engages socially with a limited vocabulary.

Nonsurvivors

Two of our nonsurvivors were placed on VAD as a bridge-to-decision. The first was an 18-month-old post–hybrid procedure. This patient was placed on ECMO during CPR before VAD placement for poor end-organ function without recovery. The second patient was a non-palliated HLHS with severe tricuspid regurgitation and decreased right ventricle function who was transferred to our institution at 6 weeks of age for transplant evaluation. The patient was placed on VAD support at 3 months of age as a bridge-to-end-organ recovery and possible transplant candidacy. The patient showed some end-organ recovery but eventually died of sepsis. The third nonsurvivor was a patient who progressed to liver dysfunction in the context of direct hyperbilirubinemia, starting 2 weeks post-VAD implant, with an uneventful immediate postoperative course. After an extensive evaluation, the diagnosis of gestational alloimmune hemochromatosis was confirmed based on liver and buccal biopsies and immune markers.8

Post-Transplant

Table E5 includes transplant and post-transplant factors. Table E6 includes panel reactive antibodies of the survivors at 6 and 12 months’ postimplant. No patient had any episodes of acute cellular rejection. Patient 3 died 7 months after transplant from overwhelming sepsis.

DISCUSSION

In this series, the majority of our patients had a VAD implanted as a mode of primary salvage. Three patients were postprimary surgery (status post [s/p] Norwood, s/p pulmonary artery band mitral valve repair, and s/p Hybrid procedure). Survival to discharge post-transplant was comparable among patients who were postprimary surgery and primary salvage, 2/3 versus 4/6 respectively, albeit with a small cohort. Despite the initial success of the Berlin Heart EXCOR VAD in pediatric heart failure, subsequent literature showed lower weight and single-ventricle anatomy as poor prognostic factors.1,3,9 The reasons for our improved survival in this cohort is likely multifactorial. Prepalliation selection and implantation of these patients prevents end-organ insult that is likely one of the most important factors. Four of six survivors had no surgical palliation before the VAD implant. Lower lymphocyte counts and increased CRP have been previously demonstrated to potentially indicate a state of persistent inflammation and was noted in nonsurvivors.10,11 In addition, the trends in the WBC counts and inflammatory markers in our nonsurvivors could indicate the severity of systemic organ injury from the uncorrected heart failure that could have benefited from an earlier rescue.

In Gazit and colleagues’4 cohort of patients supported by a continuous-flow device, Levitronix PediMag (Thoratec, Pleasanton, Calif), only a few patients required a CI of ≥6 L/min/m2. This, in combination with common atrial cannulation, was sufficient for effective atrial decompression. In our surgical experience, the common atrial cannulation provided easy access to the congenital heart. In addition, we noted that easier decompression and fewer issues with VAD filling. This, combined with an aggressive diuretic regimen, allows effective pulmonary and hepatic decongestion. Also, this allowed for the use of a lower CI, 3.5 to 5.0 L/min/m2 while allowing the VAD to provide adequate systemic oxygen delivery and minimize complications from VAD use. Overall, improved decompression of the heart with the combined use of medical therapy alongside the VAD likely helped end-organ recovery.

Other medical (non-VAD) options for heart failure post initial surgical palliation include tracheostomy and a concomitant gastrostomy tube while awaiting transplant. This improves freedom from sedation and increases opportunities for rehabilitation.12 Although these options exist, we propose there is a significantly increased degree of safety with VAD placement as wait times are often longer. Physical and nutritional rehabilitation is also a superior post-VAD implant.

The choice of bivalirudin as the primary method of anticoagulation is another critical factor that likely leads to improved outcomes. Bivalirudin has become increasingly popular across the pediatric VAD services with its increased efficacy in decreasing thrombotic events.13–15 Of note, 1 patient had a CNS hemorrhage and was the only patient on heparin as a primary anticoagulant. On bivalirudin, there was a single episode of multiorgan dysfunction that was suspected to be thromboembolic. The patient was too unstable to obtain imaging and slowly recovered end-organ function with no confirmatory data obtained on later imaging. Since this sentinel event, the approach to antiplatelet therapy has been modified based on the protocol by Rosenthal and colleagues.16

The 2 major complications observed in our cohort were hemolysis needing frequent transfusion and recurrent periods of inflammation/infection. Hemolysis was first noted in infant patients with dilated cardiomyopathy supported on Berlin EXCOR. In our current cohort, the degree of hemolysis was greater in patients with a PTFE graft from an outflow graft as opposed to a stented ductus. In a more recent experience, a patient, not included in this cohort with severe hemolysis and a PTFE graft, was switched to a continuous-flow device that helped with a significant decrease in hemolysis.

Both survivors and nonsurvivors had recurrent episodes of fever that warranted broad-spectrum antibiotics in the context of an indwelling peripherally inserted central line catheter and VAD cannulas, but only 2 episodes of culture-positive bacteremia occurred.

Our analysis of prognostic factors and conclusions is limited due to the small number of patients and the retrospective nature of our review. Further experience with implants is needed to optimize strategies and to implement changes to minimize complications.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of Berlin Heart EXCOR as a bridge-to-transplant is an option in supporting the high-risk peri–stage one single ventricle physiology. Critical factors contributing to improved outcomes could potentially be attributed to the timing of VAD implant, successful decompression of the circulation, the modulated use of cardiac output generated by the VAD assisted by native cardiac output, and optimization of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy. Implications of the results can also be seen in the Figure 2. There is a need for ongoing discussions on the nature of the graft for pulmonary blood flow and a better understanding of hemolysis and inflammation processes in VADs.

Supplementary Material

TABLE 2.

Individual patient profiles before, during, and after VAD implantation

| Patient number | Diagnosis | Indication for VAD | Surgery before VAD implant | Age at implant, d | Weight at implant, kg | Transplant vs death | Length of VAD support, d | Duration of admission before VAD support, d | Mechanical ventilation >10 d after VAD implant | Source of parallel blood flow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivors | ||||||||||

| 1 | HLHS MS AA large coronary sinusoids | Unfavorable Anatomy | None | 20 | 2.43 | Transplant | 162 | 20 | Yes | PDA stent as part of the hybrid procedure |

| 2 | PA/IVS with RV dependent coronary artery circulation | Signs of coronary ischemia | None | 4 | 3.47 | Transplant | 167 | 4 | Yes | Y shunt from outflow graft |

| 3 | HLHS MA AA | Inability to wean of ECMO post Norwood | Norwood procedure | 13 | 3.3 | Transplant | 12 | 13 | Yes | BT shunt |

| 4 | DILV with hypoplastic right ventricle TGA | Cardiogenic shock | PA band mitral valve repair | 1594 | 10.2 | Transplant | 11 | 66 | No | Y shunt from outflow graft |

| 5 | PA/IVS | Cardiogenic shock with signs of ischemia | PDA stent | 112 | 4.68 | Transplant | 64 | 24 | No | PDA stent |

| 6 | HLHS MA AA | Cardiogenic shock with incessant arrhythmia | None | 20 | 3.8 | Transplant | 64 | 20 | No | PDA stent as part of the hybrid procedure |

| Nonsurvivors | ||||||||||

| 7 | HLHS MS AA large coronary sinusoids | Unfavorable Anatomy | None | 18 | 3.25 | Withdrawal severe liver dysfunction | 56 | 13 | Yes | PDA stent as part of the hybrid procedure |

| 8 | HLHS MA AA | Cardiogenic shock ECPR | Hybrid procedure | 549 | 8.7 | Death from MODS post-ECMO CPR | 9 | 151 | Yes | PDA stent as part of the hybrid procedure |

| 9 | HLHS MA AA with severe tricuspid regurgitation | Late referral. heart failure with end-organ dysfunction | None | 143 | 3.85 | Death from sepsis and MODS. End-organ function made marginal improvement | 138 | 111 | Yes | PDA stent as part of the hybrid procedure |

VAD, Ventricular assist device; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; MS, mitral stenosis; AA, aortic atresia; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PA, pulmonary artery; PA/IVS, pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum; RV, right ventricle; MA, mitral atresia; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; BT, Blalock-Thomas-Taussig; DILV, double inlet left ventricle; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; ECPR, institution of extracorporeal support during cardiopulmonary resuscitation; MODS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

PERSPECTIVE.

Options for VAD implant available to treat the high-risk peri–stage one single-ventricle infant or toddler cohort are limited. This cohort is widely managed medically to transplant, due to a lack of viable options. This study conveys this cohort of patients can be bridged using pulsatile VADs, providing more options for the clinical provider.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Susan Cooke, PA-C, who drew Figure 1, A, B, and C.

This study was partially funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR000064.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BSA

body surface area

- CI

cardiac index

- CNS

central nervous system

- CPR

cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- HLHS

hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- hs-CRP

high sensitivity C-reactive protein

- PA/IVS

pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum

- POPC

pediatric overall performance category

- PTFE

polytetrafluoroethylene

- s/p

status-post

- VAD

ventricular assist devices

- WBC

white blood count

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Weinstein S, Bello R, Pizarro C, Fynn-Thompson F, Kirklin J, Guleserian K, et al. The use of the Berlin Heart EXCOR in patients with functional single ventricle. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearce FB, Kirklin JK, Holman WL, Barrett CS, Romp RL, Lau YR. Successful cardiac transplant after Berlin Heart bridge in a single ventricle heart: use of aortopulmonary shunt as a supplementary source of pulmonary blood flow. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:e40–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conway J, St Louis J, Morales DLS, Law S, Tjossem C, Humpl T. Delineating survival outcomes in children <10 kg bridged to transplant or recovery with the Berlin Heart EXCOR ventricular assist device. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gazit AZ, Petrucci O, Manning P, Shepard M, Baltagi S, Simpson K, et al. A novel surgical approach to mechanical circulatory support in univentricular infants. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:1630–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philip J, Lopez-colon D, Samraj RS, Kaliki G, Irwin MV, Pietra BA, et al. End-organ recovery post-ventricular assist device can prognosticate survival. J Crit Care. 2018;44:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philip J, Reyes K, Ebraheem M, Gupta D, Fudge JC, Bleiweis MS. Hybrid procedure with pulsatile ventricular assist device for hypoplastic left heart syndrome awaiting transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;158:e59–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrnes JW, Bhutta AT, Rettiganti MR, Gomez A, Garcia X, Dyamenahalli U, et al. Steroid therapy attenuates acute phase reactant response among children on ventricular assist device support. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:1392–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tadros HJ, Gupta D, Childress M, Beasley G, Rubrecht AE, Shenoy A, et al. Sub-acute neonatal hemochromatosis in an infant with hypoplastic left heart syndrome on ventricular assist device awaiting transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2019;23:e13567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almond CS, Morales DL, Blackstone EH, Turrentine MW, Imamura M, Massicotte MP, et al. Berlin Heart EXCOR pediatric ventricular assist device for bridge to heart transplantation in US children. Circulation. 2013;127:1702–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu X, Larsen B, Rutledge J, West L, Ross DB, Rebeyka IM, et al. The profile of the systemic inflammatory response in children undergoing ventricular assist device support. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15:426–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan Y, Weng YG, Huebler M, Cowger J, Morales D, Franz N, et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in children after long-term ventricular assist device insertion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prodhan P, Agarwal A, Elhassan NO, Bolin EH, Beam B, Garcia X, et al. Tracheostomy among infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome undergoing cardiac operations: a multicenter analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:1308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buck ML. Bivalirudin as an alternative to heparin for anticoagulation in infants and children. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2015;20:408–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutledge JM, Chakravarti S, Massicotte MP, Buchholz H, Ross DB, Joashi U. Antithrombotic strategies in children receiving long-term Berlin Heart EXCOR ventricular assist device therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:569–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanderpluym CJ, Cantor RS, Machado D, Boyle G, May L, Griffiths E, et al. Utilization and outcomes of children treated with direct thrombin inhibitors on paracorporeal ventricular assist device support. ASAIO J. 2020;66:939–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenthal DN, Lancaster CA, McElhinney DB, Chen S, Stein M, Lin A, et al. Impact of a modified anti-thrombotic guideline on stroke in children supported with a pediatric ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:1250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.