Abstract

This study is aimed to assess the effect of both employability and personal resources, in terms of pro-activity and self-efficacy, on the relationship between job insecurity and psycho-social distress. Using survey data from 211 participants, among employed, unemployed and workers in transition, we analyzed the incidence of employability, pro-activity and self-efficacy on psycho-social distress. Our results showed that the above-mentioned variables significantly differed by participants’ gender and age. The structural theoretical model proposed to assess the significance of the hypothesized paths exhibited good fit with the data. Thus, all our hypotheses were supported. Findings are in line with previous research, and practical implications may give significant effects when applied in new labor policies undertaken by local governments.

Keywords: employability, psycho-social distress, personal resources, organizations

Nowadays’ sociopolitical and economic conditions seem more and more often characterized by multifarious and non-uniform connotations, more discontinuous than in the past. Work is not only a place where one’s identity can be set up or just one of the major social integration factors. It is also a source of personal wellness. Consequently, it is needed that working conditions fulfill at least some basic requirements: a job has to be reasonably stable, well paid, interesting enough, safety and dignity are totally respected. In other words, a job should comply with requirements for dignity and meaning, for both employers and job seekers (Blustein, 2011; Massimiani, 2007, 2010) respecting the characteristics of quality.

Taking into account the European Committee’s official guidelines (European Commission [2001]), the idea of job quality is referred to a complex and multi-dimensional concept, since it considers not only the opportunities of paid jobs, but also their characteristics. According to Massimiani (2010), these properties correspond to: 1) the objective characteristics of the workplace; 2) the worker’s specific characteristics; 3) the harmony between a worker’s specific characteristics and the requirements for the activity to be performed; 4) the level of personal satisfaction.

In order to have a unitary analysis framework, the same European Commission (2001) identified a number of job quality components, included in two macro-categories: 1) the characteristics of the workplace, regarding the intrinsic quality of the job (type of contract, work shifts, competence required), and life-long learning and career development processes; 2) the characteristics of workplace and labor market (gender equality, work health and safety, flexibility and inclusion, work-life balance, diversity and productivity).

The aim of the present study was to analyze the relationship between job insecurity and psycho-social disturbances during job transitions or when people start working after a jobless period. Specifically, the main goal was to verify how two personal resources—self-efficacy and pro-activity—together with one’s own perception of employability may mediate the relationship between one’s status of insecurity and situations of unease or illness.

Job Flexibility, Job Insecurity and Personal Resources

The concept of "precariousness" that we use is that which emerges clearly from the meaning attributed to it in some "economically advanced" countries (Standing, 2011). Regardless of the possible and different interpretations, the perception of job insecurity undoubtedly represents a clear risk factor for the health of individuals and their families, ending up as one of the main sources of different forms of psychological distress and discomfort (Girardi et al., 2015). The extreme discretion of most jobs in the modern European market and the consequent flexibility of work are certainly the main reasons for job insecurity. Autonomy, independence and new technologies have brought us towards a work individualization process and an increased sense of insecurity due to the consequent occurrence of profiles bound to have “boundaryless” careers; this gain even more importance in the case of atypical workers. The status of “job insecurity” lies in an extremely flexible context, between having a job activity and being jobless. Its perception varies between the “subjective” and the “objective,” depending on the real risk of losing one’s job. The impact of this condition on health is remarkable and several authors argue that it can be more powerful than joblessness. The recessionary cycles that can periodically affect more or less developed geographic areas, or even global health crises such as the recent coronavirus disease (COVID) pandemic, cause unexpected shocks on the employment systems to the point of requiring absolutely new and exceptional occupational recovery strategies, totally distant from the application of traditional tools for effective employability of workers (Buffel, Velde, & Bracke, 2015; Giorgi, Arcangeli, Mucci, & Cupelli, 2015; Mucci, Giorgi, Roncaioli, Fiz Perez, & Arcangeli, 2016). Precisely in relation to the COVID crisis, based on preliminary estimates by the International Labor Organization (ILO), the economic and labor crisis caused by COVID-19 could increase unemployment in the world by almost 25 million. The estimates indicate an increase in global unemployment from 5.3 to 24.7 million. This would add up to 188 million unemployed people in the world in 2019. As the ILO estimates that between 8.8 and 35 million more people will find themselves in conditions of working poverty worldwide, the same organization has outlined guidelines guides that aim to provide immediate responses to the "unemployment" emergency. Of all, we limit ourselves to: a) strengthening of measures on health and safety at work; b) restructuring of the organization of work with smart working tools; c) wider access to health for all workers; d) strengthening the capacity and resilience of employers' and trade union organizations; e) strengthening of social dialogue, collective bargaining and industrial relations; f) strengthening of the governance (ILO, 2020; Green, 2020; Kazmi, Hasan, Talib, & Sagar, 2020).

Regarding the above-mentioned aspects, most recent studies on employability (Cai et al., 2015; Kim, Kim, & Lee, 2015; Lodi, Zammitti, Magnano, Patrizi, & Santisi, 2020; Lo Presti, Pluviano, & Briscoe, 2018) have shown that the most important set of personal resources needed to manage one’s unease deriving from job insecurity are mostly to be found in everyone’s Psychological Capital (PsyCap). This is both in its original structure and formulation (Luthans, Youssef, & Avolio, 2007), and in the more recent attempts to reinforce the idea through new constructs, like Emotional Intelligence (Di Fabio & Palazzeschi, 2016; Magnano, Santisi, & Platania, 2017), Risk Intelligence and Courage (Magnano, Paolillo, Platania, & Santisi, 2017).

PsyCap can be described as the psychological state of an individual who is able to: 1) focus on his or her self-efficacy in order to be able to perform demanding tasks; 2) carry out positive assignments—optimism—on what is happening now and what could happen in the future; 3) persevere towards one's goals and, if necessary, redirect the paths towards the desired goals—hope—to achieve success; 4) get together and go further to achieve success—resilience—if affected by problems and adversity (Luthans et al., 2007).

Although each of the four components of PsyCap is conceptually and empirically independent, research has shown that it has a common psychological substrate that actually binds them together (Luthans & Youssef, 2007) and which represents its added value, the latent dimension that holds all secondary dimensions together. Individuals with higher levels of PsyCap have greater psychological resources and, in organizational contexts, enjoy greater advantages than those with high levels of one or two dimensions. Taken in its entirety, PsyCap offers a further contribution to predicting future performances with respect to its secondary dimensions considered separately (Consiglio & La Mura, 2015; Luthans & Youssef, 2007).

Moreover, PsyCap goes beyond the consolidated theories about the human capital (“what you know”), emphasizing the aspects of “who you are” and “what you are turning into” (Avolio & Luthans, 2006; Luthans & Avolio, 2004). Also, for this reason, the PsyCap multidimensional and dynamic construct is complemented by specific motivational configurations and behavior styles, expression of an individual’s subjective potentiality, that is a personal and valuable endowment linked to adaptive decisional strategies to overcome obstacles and achieve the goals set. For the purpose of this survey and its operative design the authors have used only one of the constructs constituting the Psychological Capital, that is the perception of self-efficacy.

In accordance with the theoretical pattern proposed by Luthans and Youssef (2004), the first PsyCap sub-dimension is self-efficacy, directly derived from Albert Bandura’s socio-cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986). It is described as the “belief of having the ability to organize and carry out action sequences required to produce certain results which have an impact on the subject’s commitment, the choice of the objectives and the performance” (Luthans & Youseff, 2004, p. 153).

Generally, self-effective people choose more difficult tasks and more stimulating objectives because they know they are able to succeed; their motivation increases in complex situations and their perseverance enhances in front of obstacles. Researchers have also showed that self-efficacy is accompanied by a greater spirit of initiative, higher levels of determination and motivation (Bandura, 1997; Bandura & Locke, 2003), higher job satisfaction and perceived wellness, lesser turnover and, obviously, better job performances (Avey, Luthans, & Jensen, 2009; Hodges, 2010; Luthans et al., 2007; Platania, Santisi, Magnano, & Ramaci, 2015).

Employability

It is now clear that job insecurity conditions can be effectively (as a process) and positively (in terms of results) moderated and managed only by the workers’ objective skills, expressed according to their possibility to “re-employ themselves” in the current chaotic labor market. In other words, we need to try to understand which employability thresholds an individual can express to pursue the objective of a “dignified job” and properly face the psycho-physical impact of his/her job insecurity condition.

Some of the examined aspects are represented by alternatives to linear and hierarchical career patterns (Arthur & Rousseau, 1996; Pieperl & Baruch, 1997), as well as changing psychological contracts (Herriot & Pemberton, 1996; Rousseau, 1995, 2001; Sparrow, 1996). Most researchers focused on management matters such as the negative impact these trends may have on people’s attitude at work and on their affection towards their work company. Some authors (Baruch, 1998) argue that the traditional organization affection is to be wished for employees and a more individual work and career pattern is to be promoted, underlining the aspects which go beyond the organization, like the no-limit career (Arthur, 1994; Bird, 1994).

Changing from stable and long term into shorter, flexible and unsteady work relationships (Hiltrop, 1995), employable individuals generally seek places which can offer them career opportunities and possibilities of improving their know-how and skills (Baruch, 2001; Kluytmans & Ott, 1999). Some authors (Berntson, Näswall, & Sverke, 2010) believe that those who think of themselves as “employable” perceive themselves as if they had more opportunities in the labor market, and they will likely depart from the organization more rapidly than those who “do not feel employable.”

Due to its contradictory and confused nature, the idea of employability has often been doubted upon. Among the various critical approaches, though all dating back to the last two decades (Pascale, 1995; Rajan, van Eupen, Chappe, & Lane, 2000) Sanders and de Grip’s (Sanders & de Grip, 2004) can probably be considered as the most realistic, especially because they maintain that the meaning of employability has changed over the last 30 years, depending on the labor market conditions and policies of the time at play.

Rothwell and Arnold (2007) consider employability as a psycho-social construct (Fugate, Kinicki, & Ashforth, 2004) and define it as the ability to maintain the current job or to get the wished one; as such, it comprises: 1) individual characteristics, like knowledge and skills (Hillage & Pollard, 1998), learning abilities (Bagshaw, 1996; Lane, Puri, Cleverly, Wylie, & Rajan, 2000), mastering in managing one’s own career and in job searching (Hillage & Pollard, 1998), resilience (Iles, 1997; Rajan, 1997; Rajan et al., 2000), and self-efficacy; 2) intra-organizational factors, regarding the present and future conditions of domestic labor markets; 3) external factors, such as the foreign labor market conditions (Kirschenbaum & Mano-Negrin, 1999; Lane et al., 2000), which include those factors linked to job demands (Mallough & Kleiner, 2001).

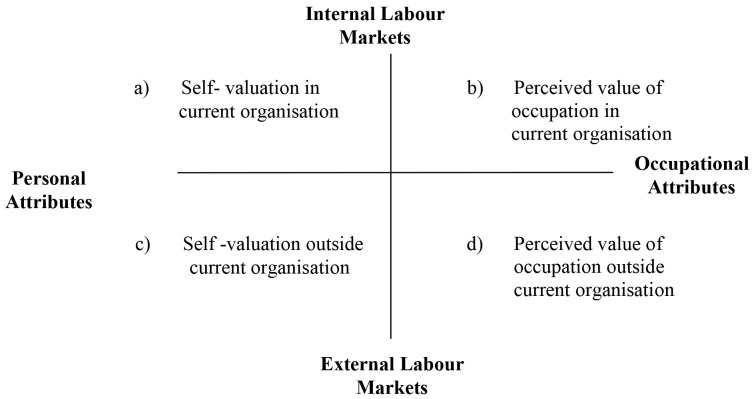

In their pattern, Rothwell and Arnold (2007) systematically show the major dimensions’ employability derives from, identifying two hypothetical lines whose ends are the foreign and domestic labor markets and the individual and work resources. The combination of these two dimensions originates four frameworks expressing the subject’s employability conditions (cfr. Figure 1): frame “a” represents the individuals’ evaluation of their own usefulness inside their work organization; frame “b” reflects the way the organization appreciates its manpower or professional team in the domestic labor market; frame “c” relates to the individual self-perception of one’s own job (mainly based on their personal competencies compared to their job characteristics) in the foreign labor market; frame “d”, finally, refers to how the foreign labor market is assessed and perceived by those with the individual’s personal experiences. These changes from job to job can also change along the way (Magnano, Santisi, Zammitti, Zarbo, & Di Nuovo, 2019).

Figure 1. Graphic Chart of Employability Conditions (Rothwell & Arnold, 2007).

Aims and Hypotheses

On the basis of the foregoing premises, job security and employability thus appear as the two constructs better able to interpret the tax flexibility requirements from the labor market. It is necessary to associate a series of potentially suitable individual resources with these two concepts for predicting the possible health consequences of a job flexibility condition.

The study research design presented below investigates the relationship between job insecurity and psychological distress. Specifically, we aim to analyze the relationship between job insecurity, employability, two individual resources (i.e., pro-activity and self-efficacy) and psychological distress.

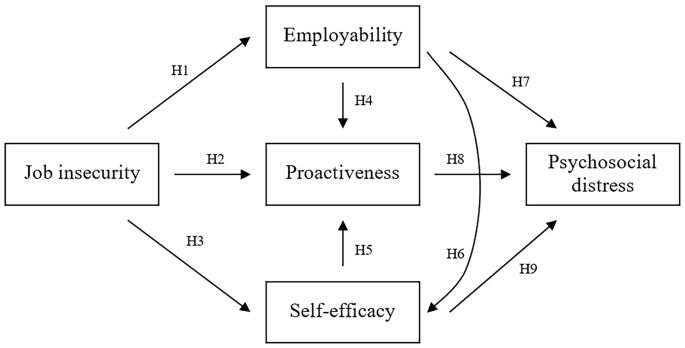

According to the theoretical model presented in Figure 2, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Figure 2. Proposed Theoretical Model.

We expected job insecurity to positively affect employability (H1), and to negatively affect proactiveness (H2) and self-efficacy (H3);

We expected employability to positively affect proactiveness (H4), and self-efficacy to negatively affect proactiveness (H5) (considering that high scores in self-efficacy indicate low self-efficacy);

We expected employability to negatively affect self-efficacy (H6) and to positively affect psychosocial distress (H7) (considering that high scores in self-efficacy indicate low self-efficacy and high scores in psychological distress indicate high psychological discomfort);

We expected proactiveness to positively affect psychosocial distress (H8) and self-efficacy to positively affect psychosocial distress (H9) (considering that high scores in psychological distress indicate high psychological discomfort and high scores in self-efficacy indicate low self-efficacy).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Two-hundred and twenty-two jobless, employed and currently unemployed participants, living in Sicily (South Italy), were examined by qualified researchers. Participants were invited to adhere on a voluntary basis, and they were informed about the aims of the study. All participants were asked to complete a self-report questionnaire, which was administered to 211 workers (95% response rate). They were also asked to indicate their gender and age, their education level, and their current and past job position. Sample characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample Characteristics (N = 211).

| Variable | Results |

|

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 121 | 57.3 |

| Female | 90 | 42.7 |

| Age | ||

| < 30 | 39 | 18.9 |

| 30–39 | 75 | 36.4 |

| 40–50 | 42 | 20.4 |

| > 50 | 50 | 24.3 |

| Schooling | ||

| Primary school | 11 | 5.2 |

| Secondary school | 38 | 18.0 |

| High school | 130 | 61.6 |

| Graduate | 32 | 15.2 |

| Work condition | ||

| Jobless | 101 | 47.9 |

| Employed | 88 | 41.7 |

| Currently unemployed | 22 | 10.4 |

| Job position in progress or in the past | ||

| Manager | 14 | 6.7 |

| Employee | 71 | 33.6 |

| Workman | 67 | 31.7 |

| Consultant | 34 | 16.2 |

| Unresponsive | 25 | 11.8 |

Measures

This study was conducted using a set of questionnaires. The instruments used were the following:

The Job Insecurity Scale (JIS)

The JIS (Sverke et al., 2004, Italian version) was used to evaluate the perception of insecurity. It is composed of a five-item scale. The response scale was on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). High scores indicate high job security. Cronbach’s alpha was .85.

The Employability Perceived Scale (EPS)

The EPS (Lo Presti & Nonnis, 2008) was used to assess the individual perception about the probability of getting a new job. The tool is based on a five-item scale to which one responds on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = no probability; 5 = 100% probability). Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

The Career Transitions Inventory (CTI) for Proactivity (PROACT) and Self-efficacy (SE)

The PROACT and the SE were measured using two CTI subscales (Heppner, Multon, & Johnston, 1994; Lo Presti, 2008). These multidimensional scales were administered to evaluate the perception of psychological resources in career transition workers. The PROACT was assessed by 13 items to which one responds on a 6-point Likert Scale. Cronbach’s alpha was .85. The SE is a tool based on 10 items evaluating on a 6-point Likert Scale the degree of perceived self-efficacy in successfully completing a change in one’s work. High scores indicate low self-efficacy. Cronbach’s alpha was .68.

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)

The GHQ-12 (Goldberg, 1979; Piccinelli, Bisoffi, Bon, Cunico, & Tansella, 1993) is designed to measure the level of individual distress, based on 12 items on a 6-point Likert Scale (1 = less than usual; 6 = more than usual). High scores indicate high psychosocial discomfort. Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

Socio-Demographic Variables

In the last part of the questionnaire, participants provided information about the socio-demographic characteristics, such as gender, age, school grade, occupational history (as years of service), working conditions, and job position, that might be associated with proactiveness, psychological distress and job insecurity.

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed with the software SPSS (Version 22.0) for Mac. Descriptive analyses were performed using frequencies (percentages). Test scores were reported as mean and standard deviation. Both t-tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed to determine any statistically significant differences between the groups’ means.

Robust maximum likelihood structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to test the hypothesized model. The SEM analyses were performed with EQS Structural Equation Program (Version 6.1; Bentler, 2006). The goodness of fit of the proposed model to the empirical data was evaluated using the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square (SBS χ2) goodness-of-fit test. As chi-square is sensitive to sample size, we followed Bollen’s (1989) recommendation to use multiple fit indices for interpreting the fit of the model with data. In addition to the chi-square statistic, we examined the chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ2/df), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), non-normed fit index (NNFI), and comparative fit index (CFI). Acceptable model fit typically is inferred when RMSEA is .08 or lower, both CFI and NNFI is above .90, and the ratio of chi square to degree of freedom is above 1 and less than 3 (Brown, 2006; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Descriptive Analysis

The results showed statistically significant differences in employability (EPS), proactiveness (PROACT) and job insecurity (JIS) by both participants’ gender and age. That is, different mean scores on the aforementioned measures were found in the comparison between male and female participants, and among the subgroups originated by sample’s age (≤ 30 years; 30–39 years; 40–49 years; ≥ 50).

Table 2 displays statistically significant scores obtained from questionnaires. Job insecurity (JIS) shows statistical differences related to gender (M = 3.58 ± 0.302): women show higher scores than their male colleagues (t = 3.05; p = .003).

Table 2. Scores Obtained From Scales.

| Variable | EPS | PROACT | SE | GHQ-12 | JIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1.85 ± 0.94 | 3.55 ± 0.91 | 3.01 ± 0.75 | 2.19 ± 0.67 | 4.13 ± 3.14 |

| Female | 1.65 ± 0.72 | 3.44 ± 0.87 | 3.11 ± 0.72 | 2.38 ± 0.67a | 2.84 ± 2.71a |

| Age | |||||

| ≤ 30 | 2.03 ± 0.71a | 3.72 ± 0.55a | 3.08 ± 0.57 | 2.28 ± 0.56 | 3.16 ± 2.90 |

| 30–39 | 1.96 ± 0.81a | 3.78 ± 0.76a | 3.13 ± 0.70 | 2.23 ± 0.69 | 3.39 ± 2.83 |

| 40–49 | 1.69 ± 0.96 | 3.39 ± 1.01a | 2.83 ± 0.64 | 2.21 ± 0.56 | 3.50 ± 3.20 |

| ≥ 50 | 1.27 ± 0.52a | 2.86 ± 0.91a | 23.11 ± 0.91 | 2.38 ± 0.82 | 4.53 ± 3.26 |

Note. EPS = Employability Perceived Scale; PROACT = Proactivity; SE = Self-efficacy; GHQ = General Health Questionnaire; JIS = Job Insecurity Scale.

aStatistically significant difference.

The scores regarding employability—EPS were significantly lower. As age increased, a progressive reduction of the scores is observed in all five items. ANOVA test shows statistically significant reductions: in age bands > 30 years as to < 50.

Regarding the perception of psychological resources available to the individual who is experiencing a career transition (CTI): PROACT useful for measuring the motivation of individuals in addressing a work transition receives high scores (M = 5.92 ± 3.50): as age increased, a progressive reduction of the scores was observed also in this case. Even the scores attributed to the feeling of SE in successfully completing a work change were undoubtedly positive (in this case, low scores corresponded to more positive judgments; M = 3.05 ± 7.34).

The measurement of mental and physical discomfort levels (GHQ-12) experienced in recent weeks receives high average scores (3.58 ± 3.02), reflecting high levels of individual malaise. Results reveal statistically significant differences in favor of females (t = −2.27, p = .024).

Structural Model Testing

We evaluated the structural model shown in Figure 2 and the significance of the hypothesized paths. The proposed theoretical model exhibited good fit with the data. Although the chi-square statistics were significant, SBS χ2 (765) = 953.56, p < .05, the ratio of chi-square to the degrees of freedom was less than 3, χ2/df = 1.25, indicating a good level of fit of the structural model with the data. The other fit indices also indicated good fit between the proposed model and the observed data (RMSEA = .04, confidence interval = .31–.47; NNFI = .93; CFI = .94).

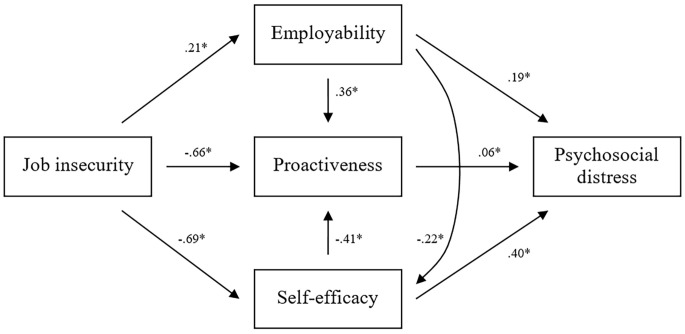

All standardized paths’ coefficients in the model were statistically significant (p < .05) and in the expected direction. Specifically, the path running from job insecurity to employability was statistically significant (β = 0.21, p < .05), offering support for Hypothesis H1; the path running from job insecurity to proactiveness was statistically significant (β = −0.66, p < .05), offering support for Hypothesis H2; the path running from job insecurity to self-efficacy was statistically significant (β = −0.69, p < .05), offering support for Hypothesis H3; the path running from employability to proactiveness was statistically significant (β = 0.36, p < .05), offering support for Hypothesis H4; the path running from self-efficacy to proactiveness was statistically significant (β = −0.41, p < .05), offering support for Hypothesis H5; the path running from employability to self-efficacy was statistically significant (β = −0.22, p < .05), offering support for Hypothesis H6; the path running from employability to psychosocial distress was statistically significant (β = 0.19, p < .05), offering support for Hypothesis H7; the path running from proactiveness to psychosocial distress was statistically significant (β = 0.06, p < .05), offering support for Hypothesis H8; the path running from self-efficacy to psychosocial distress was statistically significant (β = 0.40, p < .05), offering support for Hypothesis H9. Thus, all our hypotheses were supported. The SEM results with standardized path coefficients estimates are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Structural Equation Modelling Results With Standardized Path Estimates.

*p < .05.

Discussion

The post-modern era is characterized by profound changes in meaning individuals and groups give to work experience. Furthermore, career transitions are becoming more frequent and more challenging in the face of uncertain employment prospects. Employability is thus configured as any worker’s personal characteristics, since it focuses, on the one hand, on the possession of updated professional skills, on the other hand on adaptive skills which make workers capable of increasing their chances of finding employment (Fugate et al., 2004).

Within this framework, this study is aimed to assess the effect of employability and two personal resources (pro-activity and self-efficacy) on the relationship between job insecurity and psycho-social distress (Ramaci, Bellini, Presti, & Santisi, 2019; Ramaci, Pellerone, Ledda, & Rapisarda, 2017).

Our results showed that employability, pro-activeness, psychological distress and job insecurity significantly differed by participants’ gender and age. All the paths running hypothesized in our proposed theoretical model were verified, showing the role of the use of strategies focused on finding employment. Particularly: (1) high levels of employability are positively related to a neat reduction of the time taken to find a job and a better chance of keeping it (Nauta, Vianen, van der Heijden, van Dam, & Willemsen, 2009); (2) the relationship between employability and job placement is mediated by the use of strategies focused on seeking employment (De Battisti, Gilardi, Guglielmetti, & Siletti, 2016); (3) psychological distress appears to be linked to employability, showing a significant relationship with the adoption of non-rational job search strategies (Ingusci, Manuti, & Callea, 2016).

Therefore, the results support all our hypotheses; the negative effects of job insecurity were confirmed, and clear empirical evidence emerged about the positive effects of a versatile career orientation. Although with differentiated effects, these variables positively influenced the perception of self-efficacy necessary to manage their employment situation, with final consequences on the psycho-physical well-being.

A large part of employability research shows the presence of approaches focused on cognitive aspects and perceptions of employability, rather than dispositional factors. Today employability is considered a strategic factor to positively address the changes taking place in the labor market, and introduces a new cultural paradigm around which to rethink actions and interventions to support employment. At the same time, research shows (Berntson et al., 2010; Girardi et al., 2015) that the perception of having a good chance to find a job is associated with a greater sense of job security and greater proactivity.

The discomfort resulting from this condition has clarified how much the labor market and the perception of the worker have changed, requiring new skills and abilities: one should be increasingly flexible and be able to adapt to the various conditions that appear and disappear quickly (Nauta et al., 2009). Employability will help people cope with the transitions and challenges of work in an evolving world of work.

This study contributed to the literature highlighting knowledge on the importance of the emotional dimension in understanding the impact of job insecurity. More specifically, the empirical evidence on the role that personal resources play (Proactive and Self Efficacy) in mitigating the impact of job insecurity on psychological distress makes more sense if it is also reflected in the sampling procedures adopted in research. Usually other research has often used convenience samples; in our case, the sample was selected within the employment offices and with the collaboration of trade union organizations. This does not eliminate the limitations that research presents, but rather offers opportunities for improvement in the future. The results highlight several implications for the development of effective management strategies and practices for the management of problems relating to job insecurity.

Limitations of Research

Overall, this study found support for the research hypotheses; however, some limitations need to be mentioned. Due to the participants’ characteristics and the small sample size, generalization of our results should be done with caution. Further, all participants were from South of Italy, representing another limit to our findings generalizations. Indeed, Italian southern regions are characterized by a higher level of unemployment and/or unstable jobs compared to northern ones. From this perspective, responses on questionnaires may be influenced by the specific socio-economic context. A heterogeneous sample according to the region of origin may reduce this possible bias. Hence, although consistent with previous findings, the same conclusions may not be warranted in different samples. Another limitation concerns the choice to take into account only one of the subdomains of PsyCap (i.e., self-efficacy), ignoring whether also the other components could mediate the relationship between job insecurity and psychosocial distress. Based on literature (Cai et al., 2015; De Cuyper et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2015; Lo Presti et al., 2018) all the four components of PsyCap are relevant to face issues related to job insecurity. After that, a methodological limitation is related to the lack of investigation of the direct relationship in the hypothesized model. That is, we did not examine how job insecurity affected psychological distress, not allowing to discriminate the direct effect from the indirect ones.

Conclusions and Implications

Studies on the effects of job insecurity on mental and physical well-being as well as on professional life quality are nowadays well known in literature. This probably also derives from the fact that career and work are no longer intended as a way of ensuring sustenance but, rather, as contexts endowed with meaningfulness (Steger, Dik, & Duffy, 2012; Šverko & Vizek-Vidović, 1995).

The interest in the idea of meaningful work has been increased remarkably over the last two decades. Most managerial-based research focused on studying ways of supplying and managing the meaningfulness, for instance through leadership or organizational culture. Most of these researches, however, turn out to be scarce and fragmentary, a large variety of sources of meaningful job being available which, however, do not handle their reciprocal relationships (Faraci, Lock, & Wheeler, 2013; Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009).

As Steger et al. (2012) point out, one of the reasons why a meaningful job becomes significant is its coherent association with the benefits for workers and organizations. It is well known today that the fundamental dilemmas of managers’ and workers’ lives revolve around the meaningfulness of work (Jackall, 1988; Magnano et al., 2019), whose consequences on psycho-physical well-being are intense and deep (Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009). A meaningless job is, indeed, often linked to higher levels of apathy and detachment from it (May, Gilson, & Harter, 2004). Meaningfulness, then, refers to the degree whereby life has emotional value and compared requests are perceived as worth of one’s investment and energy commitment (Korotkov, 1998).

From a practical perspective, it seems clear that all of these assumptions take on a remarkable role. In career counseling, the ability to instill hope in finding a job increases the chances of helping clients to cope with the uncertainties of the future (López, Peón, & Vázquez Ordás, 2004). Results may have impact and great consequences also in terms of flexicurity, carried out by national governments as well as clear outlook/insight as far as the intermediation role and connected practices performed by Labour Agencies.

In conclusion, the present research potentially offers ideas for managerial policies. In such way, focusing on three key-dimensions (i.e., employability, job insecurity and personal resources) becomes an alternative and, likely, more fruitful reading key which can help to enter and return into the labor market, to ensure continuity and careers, as well as to give significance to one’s work identity.

Our findings can be considered as a relevant contribute addressing nowadays work-related conditions. From this point of view, employability, self-efficacy, and proactiveness can be seen as suitable protective factors and, for this reason, they should be promoted and encouraged.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no additional (i.e., non-financial) support to report.

Biographies

Tiziana Ramaci is Associate Professor at the University of Enna Kore (UKE), Italy, where she teaches Work and Organizational Psychology. Her researches has focused on Occupational Health and Safety, particularly with regard to organizational wellbeing, risk perception and job insecurity; vocational guidance and international careers. She is Member of International Commission on Organizational Health (ICOH).

Palmira Faraci, PhD, Full Professor of Psychometrics at the University of Enna “Kore,” Italy, Vice-President of the First Level Degree in Psychological Sciences and Techniques, member of the Internal Review Board (IRB), Ethics Committee for Psychological Research, and Director of the Kore Psychometrics Lab. Her research activity is focused on the issues related to methodological procedures and psychological testing, with particular reference to measurement techniques and data analysis, scale development and validation, assessment applied to personality and organizational psychology.

Giuseppe Santisi, PhD, is Full Professor of Work and Organizational Psychology and Economic and Consumer Psychology at the Department of Educational Sciences—University of Catania. His research interest includes organizational behavior, human resources development, organizational well-being, economic and consumer psychology. He is the author of several publications related to these topics. Currently he is Coordinator of Degree Course in Psychology.

Giusy Danila Valenti is a PhD and Research Fellow at the Faculty of Human and Social Sciences, Kore University of Enna. Her main research interest includes personality assessment, with a focus on construction and validation of psychometric tests.

Ethical Approval

The paper reports a study that has been conducted in accordance with APA ethical standards. The protocol was in line with ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki; before taking part in the study, participants were informed about any relevant aspect of the study (e.g., methods, institutional affiliations of the researcher); they were informed of the right to refuse to participate in the study or to withdraw consent to participate at any time during the study without reprisal. They then confirmed that they understood the instructions well, verbally accepted to participate, and started filling out the anonymous questionnaire. The Internal Ethic Review Board (IERB) of the Department of Educational Sciences—University of Catania, Italy, approved the present research. The data were collected from May to September 2018.

The authors have no funding to report.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Arthur, M. B. (1994). The boundaryless career: A new perspective for organizational inquiry. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(4), 295–306. 10.1002/job.4030150402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, M. B., & Rousseau, D. M. (1996). A career lexicon for the 21st century. Academy of Management Executive, 10(4), 28–39. 10.5465/ame.1996.3145317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., & Jensen, S. M. (2009). Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Human Resource Management, 48(5), 677–639. 10.1002/hrm.20294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B. J., & Luthans, F. (2006). The high impact leader: Moments matter in accelerating authentic leadership development. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Bagshaw, M. (1996). Creating employability: How can training and development square the circle between individual and corporate interest? Industrial and Commercial Training, 28(1), 16–18. 10.1108/00197859610105431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY, USA: Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A., & Locke, E. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 87–99. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y. (1998). The rise and fall of organizational commitment. Human Systems Management, 17(2), 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y. (2001). Employability: A substitute for loyalty? Human Resource Development International, 4(4), 543–566. 10.1080/13678860010024518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M. (2006). EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino, CA, USA: Multivariate Software. [Google Scholar]

- Berntson, E., Näswall, K., & Sverke, M. (2010). The moderating role of employability in the association between job insecurity and exit, voice, loyalty and neglect. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 31(2), 215–230. 10.1177/0143831X09358374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bird, A. (1994). Careers as repositories of knowledge: A new perspective on boundaryless careers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(4), 325–344. 10.1002/job.4030150404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blustein, D. L. (2011). A relational theory of working. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 1–17. 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY, USA: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buffel, V., Velde, S. V. D., & Bracke, P., (2015). The mental health consequences of the economic crisis in Europe among the employed, the unemployed, and the non-employed, Social Science Research, 54, 263–288. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z., Guan, Y., Li, H., Shi, W., Guo, K., Liu, Y., … Hua, H. (2015). Self-esteem and proactive personality as predictors of future work self and career adaptability: An examination of mediating and moderating processes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 86–94. 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2001). Employment in Europe 2001: Recent trends and prospects Luxembourg, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Consiglio, C., & La Mura, V. (2015). Lo PsyCap secondo Luthans. In A. Rolandi (Ed.), Capitale psicologico. Un asset chiave del terzo millennio (pp. 92–117). Milano, Italy: Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- De Battisti, F., Gilardi, S., Guglielmetti, C., & Siletti, E. (2016). Perceived employability and reemployment: Do job search strategies and psychological distress matter? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(4), 813–833. 10.1111/joop.12156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Cuyper, N., Mäkikangas, A., Kinnunen, U., Mauno, S., & Witte, H. D. (2012). Cross-lagged associations between perceived external employability, job insecurity, and exhaustion: Testing gain and loss spirals according to the conservation of resources theory. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(6), 770–788. 10.1002/job.1800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A., & Palazzeschi, L. (2016). Marginalization and precariat: The challenge of intensifying life construction intervention. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 444. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraci, P, Lock, M., & Wheeler, R. (2013). Assessing leadership decision-making styles: Psychometric properties of the Leadership Judgement Indicator. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 6, 117–123. 10.2147/PRBM.S53713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14–38. 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, G., Arcangeli, G., Mucci, N., & Cupelli, V. (2015). Economic stress in the workplace: The impact of fear of the crisis on mental health. Work, 51(1), 135–142. 10.3233/WOR-141844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardi, D., Falco, A., De Carlo, A., Benevene, P., Comar, M., Tongiorgi, E., & Bartolucci, G. B. (2015). The mediating role of interpersonal conflict at work in the relationship between negative affectivity and biomarkers of stress. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(6), 922–931. 10.1007/s10865-015-9658-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, D. (1979). Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. London, United Kingdom: NFER Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A. (2020, April 28). Estimates of the local impact in the West Midlands of the OBR scenario of a 35% reduction in real GDP in Q2 2020 [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/cityredi/estimates-of-the-local-impact-in-the-west-midlands-of-the-obr-scenario-of-a-35-reduction-in-real-gdp-in-q2-2020/

- Heppner, M. K., Multon, K. D., & Johnston, J. A. (1994). Assessing psychological resources during career change: Development of Career Transitions Inventory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44(1), 55–74. 10.1006/jvbe.1994.1004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herriot, P., & Pemberton, C. (1996). Contracting careers. Human Relations, 49(6), 757–789. 10.1177/001872679604900603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hillage, J., & Pollard, E. (1998). Employability: Developing a framework for policy analysis (Report No. RR85). Brighton, United Kingdom: Institute for Employment Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Hiltrop, J. M. (1995). The changing psychological contract: The human resource challenge of the 1990s. European Management Journal, 13(3), 286–294. 10.1016/0263-2373(95)00019-H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, D., (2010). An experimental study of the impact of psychological capital on performance, engagement, and the contagion effect [Dissertation, College of Business Administration—University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE, USA]. DigitalCommons. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iles, P. (1997). Sustainable high potential career development: A resource-based view. Career Development International, 2(7), 347–353. 10.1108/13620439710187981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingusci, E., Manuti, A., & Callea, A. (2016). Employability as mediator in the relationship between the meaning of working and job search behaviours during unemployment. Electronic Journal of Applied Statistical Analysis, 9(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. (2020). ILO monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work (3rd ed.). Updated estimates and analysis. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_743146.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jackall, R. (1988). Moral mazes: The world of corporate managers. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kazmi, S. S. H., Hasan, K., Talib, S., & Sagar, S. (2020). COVID-19 and lockdwon: A study on the impact on mental health. Mukt Shabd Journal, 9(4), 1477–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S., Kim, H., & Lee, J. (2015). Employee self-concepts, voluntary learning behavior, and perceived employability. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(3), 264–279. 10.1108/JMP-01-2012-0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschenbaum, A., & Mano-Negrin, R. (1999). Underlying labour market dimensions of “opportunities”: The case of employee turnover. Human Relations, 52(10), 1233–1255. 10.1177/001872679905201001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kluytmans, F., & Ott, M. (1999). The management of employability in the Netherlands. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 261–272. 10.1080/135943299398357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkov, D. L. (1998). The sense of coherence: Making sense out of chaos. In P. T. P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 51–70). Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, D., Puri, A., Cleverly, P., Wylie, R., & Rajan, A. (2000). Employability: Bridging the gap between rhetoric and reality. Second report: Employee’s perspective. London, United Kingdom: Create. [Google Scholar]

- Lips-Wiersma, M., & Morris, L. (2009). Discriminating between “meaningful work” and the “management of meaning”. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(3), 491–511. 10.1007/s10551-009-0118-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lodi, E., Zammitti, A., Magnano, P., Patrizi, P., & Santisi, G. (2020). Italian adaption of self-perceived employability scale: Psychometric properties and relations with the career adaptability and well-being. Behavioral Sciences, 10(5), 82. 10.3390/bs10050082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López, S. P., Peón, J. M. M., & Vázquez Ordás, C. J. (2004). Managing knowledge: The link between culture and organizational learning. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(6), 93–104. 10.1108/13673270410567657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Presti, A. (2008). Nuovi orientamenti di carriera e qualità del lavoro: Un contributo di ricerca [New career attitudes and quality of employment] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Presti, A., & Nonnis, M. (2008). Moderated effects of job insecurity on work engagement and distress. TPM, 19(2), 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Presti, A., Pluviano, S., & Briscoe, J. P. (2018). Are freelancers a breed apart? The role of protean and boundaryless career attitudes in employability and career success. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(3), 427–442. 10.1111/1748-8583.12188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. (2004). Humans, social, and now positive Psychological Capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organizational Dynamics, 33(2), 143–160. 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2004.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. (2007). Emerging positive organizational behavior. Journal of Management, 33(3), 321–349. 10.1177/0149206307300814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2007). Psychological capital: Developing the human competitive edge. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magnano, P., Paolillo, A., Platania, S., & Santisi, G. (2017). Courage as a potential mediator between personality and coping. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 13–18. 10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magnano, P., Santisi, G., & Platania, S. (2017). Emotional intelligence as mediator between burnout and organizational outcomes. International Journal of Work Organization and Emotion, 8(4), 305–320. 10.1504/IJWOE.2017.089295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magnano, P., Santisi, G., Zammitti, A., Zarbo, R., & Di Nuovo, S. (2019). Self-perceived employability and meaningful work: The mediating role of courage on quality of life. Sustainability, 11, 764. 10.3390/su11030764 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallough, S., & Kleiner, B. H. (2001). How to determine employability and wage earning capacity. Management Research News, 24(3/4), 118–122. 10.1108/01409170110782847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massimiani, C. (2007). Riferimenti sulla qualità del lavoro nell’Agenda di Lisbona. DLRI, 1, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Massimiani, C. (2010). La qualità del lavoro nell'esperienza dell'OIL e nelle politiche sociali europee. Morrisville, NC, USA: Lulu Press. [Google Scholar]

- May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The Psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. 10.1348/096317904322915892 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mucci, N., Giorgi, G., Roncaioli, M., Fiz Perez, J., & Arcangeli, G. (2016). The correlation between stress and economic crisis: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 983–993. 10.2147/NDT.S98525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauta, A., van Vianen, A., van der Heijden, B., van Dam, K., & Willemsen, M. (2009). Understanding the factors that promote employability orientation: The moderating impact of employability culture. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 82(2), 233–251. 10.1348/096317908X320147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascale, R. (1995). In search of the new employment contract. Human Resources, 12(6), 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Piccinelli, M., Bisoffi, G., Bon, M. G., Cunico, L., & Tansella, M. (1993). Validity and test-retest reliability of the Italian version of the 12-item General Health Questionnaire in general practice: A comparison between three scoring methods. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 34(3), 198–205. 10.1016/0010-440X(93)90048-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieperl, M., & Baruch, Y. (1997). Back to square zero, the post-corporate career. Organizational Dynamics, 25(4), 7–23. 10.1016/S0090-2616(97)90033-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Platania, S., Santisi, G., Magnano, P., & Ramaci, T. (2015). Job satisfaction and organizational well-being queried: A comparison between the two companies. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191, 1436–1441. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, A. (1997). Employability in the finance sector: Rhetoric vs reality. Human Resource Management Journal, 7(1), 67–78. 10.1111/j.1748-8583.1997.tb00275.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, A., van Eupen, P., Chapple, K., & Lane, D. (2000). Employability: Bridging the gap between rhetoric and reality: First report: Employer’s perspective. London, United Kingdom: Create. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaci, T., Bellini, D., Presti, G., & Santisi, G. (2019). Psychological flexibility and mindfulness as predictors of individual outcomes in hospital health workers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1302. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaci, T., Pellerone, M., Ledda, C., & Rapisarda, V. (2017). Health promotion, psychological distress, and disease prevention in the workplace: A cross-sectional study of Italian adults. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 10, 167–175. 10.2147/RMHP.S139756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, A., & Arnold, J. (2007). Self-perceived employability: Development and validation of a scale. Personnel Review, 36, 23–41. 10.1108/00483480710716704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D. M. (2001). Schema, promise and mutuality: The building blocks of the psychological contract. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74(4), 511–542. 10.1348/096317901167505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, J., & de Grip, A. (2004). Training, task flexibility and the employability of low-skilled workers. International Journal of Manpower, 25(1), 73–89. 10.1108/01437720410525009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, P. R. (1996). Transitions in the psychological contract: Some evidence from the banking sector. Human Resource Management Journal, 6(4), 75–92. 10.1111/j.1748-8583.1996.tb00419.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Standing, G. (2011). The Precariat: The new dangerous class. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337. 10.1177/1069072711436160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., Näswall, K., Chirumbolo, A., De Witte, H., & Goslinga, S. (2004). Job insecurity and union membership: European unions in the wake of flexible production. Brussels, Belgium: P.I.E.-Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Šverko, B., & Vizek-Vidović, V. (1995). Studies of the meaning of work: Approaches, models, and some of the findings. In D. E. Super & B. Sverko (Eds.), Life roles, values, and careers (pp. 3–21). San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]