Abstract

Background

Circumcision is a painful procedure that many newborn males undergo in the first few days after birth. Interventions are available to reduce pain at circumcision; however, many newborns are circumcised without pain management.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effectiveness and safety of interventions for reducing pain at neonatal circumcision.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2004), MEDLINE (1966 ‐ April 2004), EMBASE (1988 ‐ 2004 week 19), CINAHL (1982 ‐ May week 1 2004), Dissertation Abstracts (1986 ‐ May 2004), Proceedings of the World Congress on Pain (1993 ‐ 1999), and reference lists of articles. Language restrictions were not imposed.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing pain interventions with placebo or no treatment or comparing two active pain interventions in male term or preterm infants undergoing circumcision.

Data collection and analysis

Two independent reviewers assessed trial quality and extracted data. Ten authors were contacted for additional information. Adverse effects information was obtained from the trial reports. For meta‐analysis, data on a continuous scale were reported as weighted mean difference (WMD) or, when the units were not compatible, as standardized mean difference.

Main results

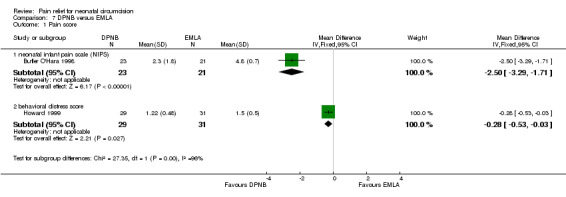

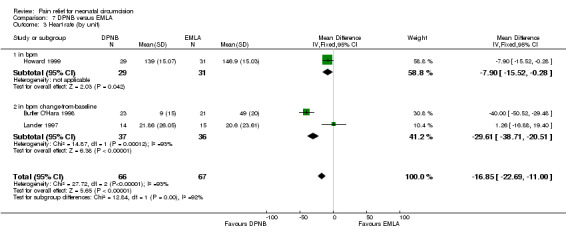

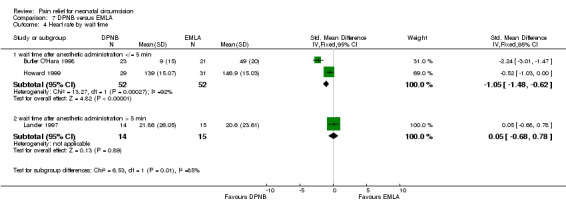

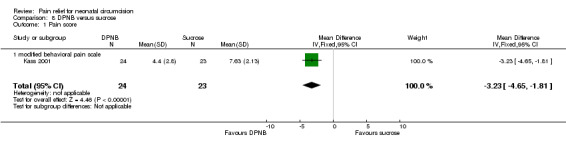

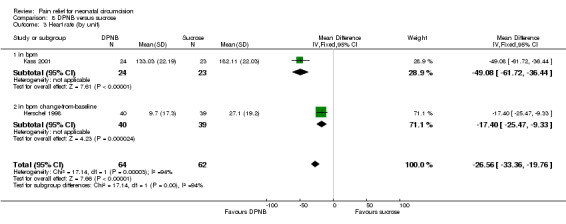

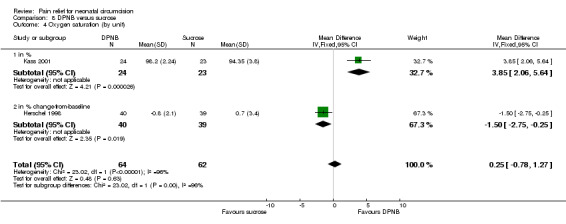

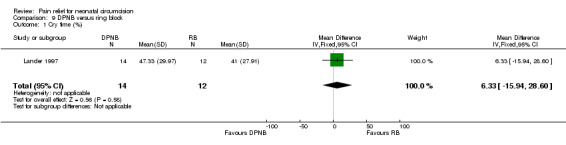

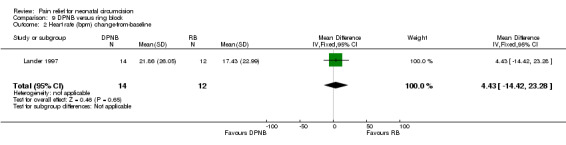

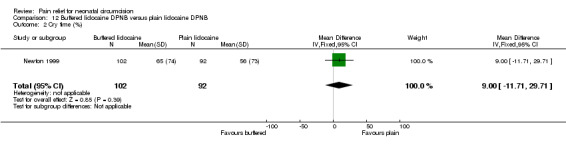

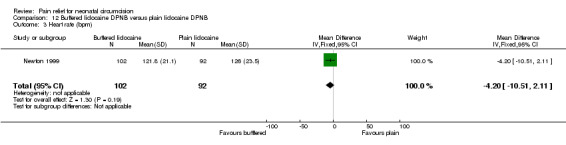

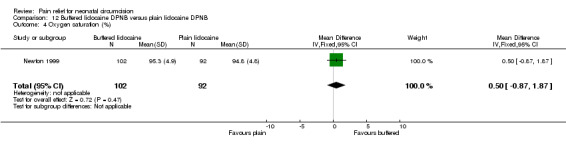

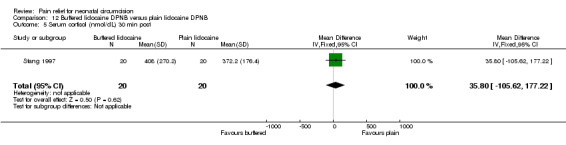

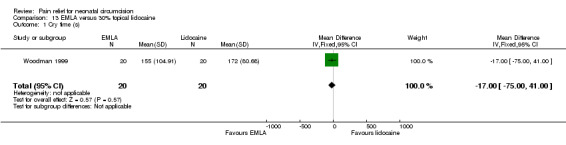

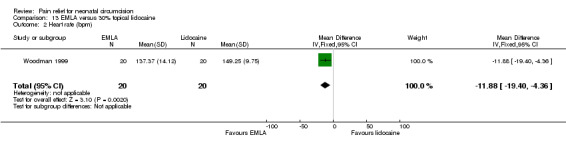

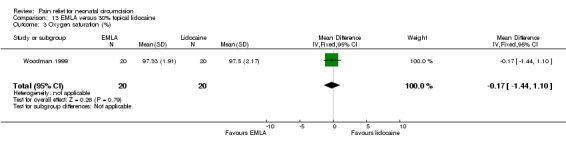

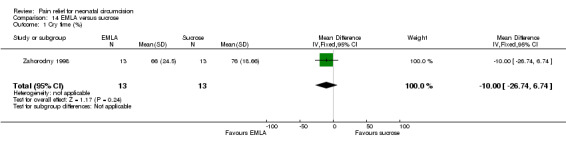

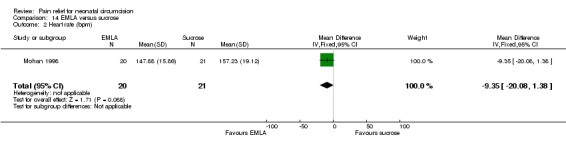

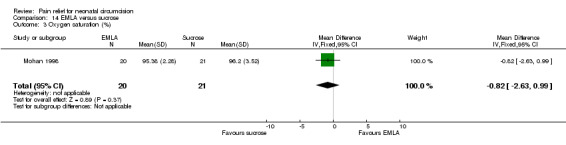

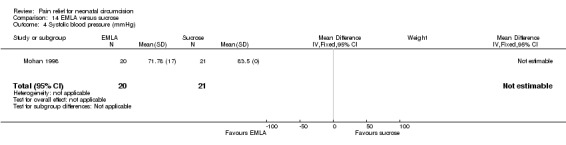

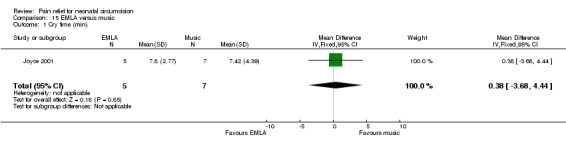

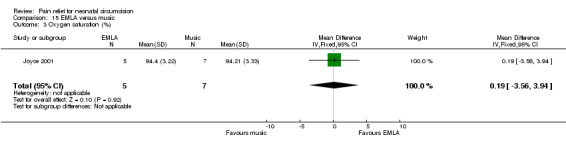

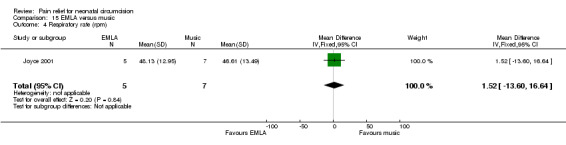

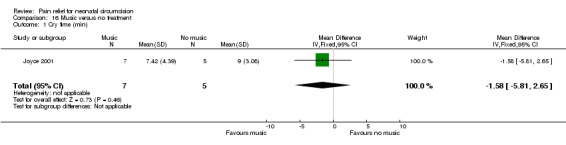

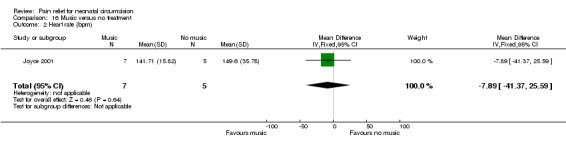

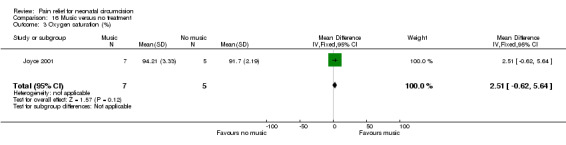

Thirty‐five trials involving 1,997 newborns were included. Thirty‐three trials enrolled healthy, full term neonates, and two enrolled infants born preterm. Fourteen trials involving 592 newborns compared dorsal penile nerve block (DPNB) with placebo or no treatment. Compared to placebo/no treatment, DPNB demonstrated significantly lower heart rate [WMD ‐35 bpm, 95% CI ‐41 to ‐30], decreased time crying [WMD ‐54 %, 95% CI ‐64 to ‐44], and increased oxygen saturation [WMD 3.7 %, 95% CI 2.7 to 3.7]. Six trials involving 200 newborns compared eutectic mixture of analgesics (EMLA) with placebo. EMLA demonstrated significantly lower facial action scores [WMD ‐46.5, 95% CI ‐80.4 to ‐12.6], decreased time crying [WMD ‐ 15.2 %, 95% CI ‐21 to ‐9.3] and lower heart rate [WMD ‐15 bpm, 95% CI ‐19 to ‐10]. DPNB, compared with EMLA in three trials involving 139 newborns (133 of whom were included in the analysis), demonstrated significantly lower heart rate [WMD ‐17 bpm, 95% CI ‐23 to ‐11] and pain scores. When compared with sucrose in two trials involving 127 newborns, DPNB demonstrated less time crying [MD ‐166 s, 95% CI ‐211 to ‐121], and lower heart rate [WMD ‐27 bpm, 95% CI ‐33 to ‐20]. Results obtained for trials comparing oral sucrose and oral analgesics to placebo, and trials of environmental modification were either inconsistent or were not significantly different.

Adverse effects included gagging, choking, and emesis in placebo/untreated groups. Minor bleeding, swelling and hematoma were reported with DPNB. Erythema and mild skin pallor were observed with the use of EMLA. Methaemoglobin levels were evaluated in two trials of EMLA, and results were within normal limits.

Authors' conclusions

DPNB was the most frequently studied intervention and was the most effective for circumcision pain. Compared to placebo, EMLA was also effective, but was not as effective as DPNB. Both interventions appear to be safe for use in newborns. None of the studied interventions completely eliminated the pain response to circumcision.

Plain language summary

Pain relief for neonatal circumcision

Circumcision is a painful procedure frequently performed on newborn baby boys without using pain relief. Available treatments include dorsal penile nerve block (DPNB), which involves injecting anesthetic at the base of the penis. Ring block is another form of penile block. Locally applied anesthetic creams include EMLA, a water‐based cream including lidocaine and prilocaine. Based on 35 clinical trials involving 1,997 newborns, it can be concluded that DPNB and EMLA do not eliminate circumcision pain, but are both more effective than placebo or no treatment in diminishing it. Compared head to head, DPNB is substantially more effective than EMLA cream. Ring block and lidocaine creams other than EMLA also reduced pain but did not eliminate it. Trials of oral acetaminophen, sugar solutions, pacifiers, music, and other environmental modifications to reduce circumcision pain did not prove them effective. DPNB can cause minor bruising, bleeding, or swelling at the injection site. EMLA and other lidocaine creams can cause skin color changes or local skin irritation. There is a rare risk with lidocaine creams of causing methaemoglobinaemia (blue‐baby syndrome, where the baby's blood lacks sufficient oxygen). However, two trials of EMLA for circumcision pain relief measured methaemoglobin levels and found them normal. The circumcision procedure itself, especially without pain relief, can cause short term effects such as choking, gagging, and vomiting. Long term effects of circumcision without pain relief are not well understood. Strict comparability between trials was rare. Trials used a variety of indicators to measure baby's pain. Crying time, facial expression, and sweating palms can indicate infant pain, as can increased heart rate, breathing rate, and blood pressure. Levels of chemical indicators that can be part of a pain or stress response and are present in the blood or saliva are another gauge of pain levels. Also, procedures were not generally performed in just the same way in different trials. Type of clamp used (8sing a Mogen clamp can shorten the duration of the procedure), length of wait time after injection or application of anesthetic and procedure techniques varied.

Background

Neither the American Academy of Pediatrics nor the Canadian Paediatric Society recommends routine or elective circumcision of the male newborn. Nevertheless, elective circumcision of male newborns is commonly performed in the first few days after birth. Approximately 1.2 million newborn males are circumcised in the United States annually at a cost of 150 to 270 million dollars (AAP 1999). Precise Canadian data are not available because the procedure has been delisted in many provinces, but it is estimated that 48% of male neonates born in Canada are circumcised (CPS 1996). The practice of male neonatal circumcision is not limited to North America; it is performed worldwide for religious and cultural reasons.

As an invasive, painful procedure, unanaesthetized circumcision elicits systemic stress responses in the vulnerable newborn which negatively affect major body systems. Documented physiological and behavioral responses include increased output of adrenal corticoids (Gunnar 1981; Talbert 1976), increased heart rate and respiratory rate, decreased arterial oxygen (Rawlings 1980), skin flushing, vomiting and cyanosis (Poma 1980), changes in sleep/wake state, increased crying (Anders 1974; Gunnar 1981), and diminished responsiveness to parents (Dixon 1984). Unanaesthetized circumcision has also been linked with complications such as apnea and choking (Lander 1997), gastric rupture (Connelly 1992), and recurrence of pneumothorax (Auerbach 1978). Infants circumcised without anaesthesia exhibit stronger pain responses to routine immunizations during the first six months of life than infants who were not circumcised (Taddio 1997b), suggesting that circumcision pain may exert long term effects on infant behavior.

INTERVENTIONS FOR CIRCUMCISION PAIN

Numerous interventions to prevent or reduce circumcision pain have been examined. These include penile blocks, topical anaesthetics, oral analgesia and sucrose administration, non‐nutritive sucking, music and other environmental interventions.

The technique of dorsal penile nerve block (DPNB) for newborn circumcision was first described in 1978 (Kirya 1978), and it has since been extensively evaluated. More recently, subpubic (Dalens 1989) and penile ring block techniques (Hardwick Smith 1998; Lander 1997) have been examined. Adverse effects of penile blocks appear to be limited to bruising and slight bleeding at the injection site (Snellman 1995). Of note, the rapidity of onset of the anaesthetic used for penile blocks (generally 1% lidocaine without epinephrine) is intermediate and a "wait time" of 5 minutes is recommended to achieve anaesthesia (Taddio 2001). Wait time is a concern for clinicians because it increases the total time required for the circumcision surgery; however, inadequate "wait time" influences anaesthetic effect (Kharasch 2003).

Several types of topical anaesthetics have been used for neonatal circumcision, including eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics (EMLA) and 4 to 30% lidocaine creams. EMLA is a water‐based cream that contains 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine. Compared with placebo, EMLA attenuates the pain responses of increased heart rate, facial activity and crying, and decreased oxygen saturation (Lander 1997; Taddio 1997). A meta‐analysis of three studies examining this intervention indicated that the use of EMLA results in a significantly lower increase in heart rate (from baseline) and less crying during the various phases of circumcision surgery compared to placebo. In two of the included studies, lower facial action scores suggested less pain in the EMLA treated groups compared to placebo (Taddio 2002).

Potential difficulties with drug administration and the presurgical wait time may limit the feasibility of topical anaesthesia as a pain intervention for circumcision in many settings (Lander 1997). Considerable technical skill is required to apply the drug, and to secure the occlusive dressing needed to keep it in place. For adequate absorption, EMLA must be applied for at least 60 minutes prior to surgery (Taddio 1998), and must be reapplied if the infant voids during the wait time.

Methaemoglobinaemia (MetHb), caused by oxidation of haemoglobin by the metabolites of prilocaine, is a serious but relatively rare risk associated with EMLA use in infants less than 12 months of age. A recent systematic review of the use of EMLA for acute pain in infants demonstrated that the risk of significant MetHb is low with single dose applications of 0.5 to 2g applied for 10 ‐ 180 minutes for full term neonates, and 0.5 to 1.25g applied for 3 to 180 minutes for preterm neonates (Taddio 1998). Local skin reactions, such as blanching, erythema, and edema of the skin have been reported with the use of EMLA , but these are usually transient and not considered serious.

Sucrose or other sugar solutions alone or in combination with non‐nutritive sucking have recently been recommended as interventions for procedural pain management (Mitchell 2000). Oral sucrose is thought to activate central endogenous pathways, and may stimulate release of endorphins from the hypothalamus. Non nutritive sucking (NNS) is also thought to have an analgesic‐like effect through stimulation of orotactile and mechanoreceptor mechanisms (Gibbons 2001; Mitchell 2003). The sensations created by NNS may deflect attention away from pain and facilitate self regulation because the infant is in control of the sucking. Sucrose and NNS appear to operate synergistically when offered in combination, and may provide more effective pain relief (Carbajal 1999; Gibbons 2001; Gibbons 2002). The analgesic effect of sucrose is activated within two minutes, and lasts for three to five minutes (Haouari 1999; Mitchell 2003). Although sucrose in a wide variety of dosages (concentrations from 12 to 24%, and volumes from 0.05 to 2.0 ml) has generally been found to decrease acute, procedural pain responses in neonates (Mitchell 2000; Stevens 1997), the optimal dose has not yet been identified. Meta‐analyses results indicate that a 0.24g dose is effective to reduce pain responses in term infants, and higher doses do not appear to increase effectiveness (Stevens 1997). In comparison, relatively small doses (0.01 to 0.02g) appear to be effective for preterm infants (Johnston 1997). Interest in sucrose or other sugar solutions as a single or adjunctive intervention for circumcision pain is reflected in the design of recent research (e.g. Kass 2001; Kaufman 2002).

Acetaminophen is the most frequently prescribed non‐opioid oral analgesic used to treat mild to moderate pain in pediatric populations (Berde 2002; McGrath 1990). Acetaminophen is safe and effective for neonates and can be administered orally or rectally (Stevens 1999). Acetaminophen has been used as an intervention for circumcision pain (Howard 1994). A variety of non‐pharmacological interventions have been evaluated for treatment of acute procedural pain in neonates. In theory, these interventions provide nonpainful stimuli that compete with painful stimuli for the neonate's attention, and thus may blunt the perception of pain (Bellieni 2002). Interventions such as rocking, massage, facilitated tucking, and cuddling reduce pain responses during invasive procedures (Campos 1994; Corff 1995; Gray 2000). Music and other sounds (intrauterine, heartbeat) provide an auditory stimulus which may modulate pain perception and these have been evaluated as interventions for circumcision pain (Marchette 1989; Marchette 1991).

NEONATAL PAIN RESPONSES

It is difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for circumcision pain because newborns are non‐verbal and display stereotypic responses to a variety of painful and non‐painful stimuli. To maximize the validity of pain assessment in newborn populations three classes of pain indicators or outcomes, biochemical, physiological, and behavioural, are generally employed for research. Salivary and serum cortisol, the most frequently measured biochemical indicators, serve as markers of the stress response to pain because hormones of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis are assayed. Physiological indicators include heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, transcutaneous oxygen saturation (Tc pO2), transcutaneous carbon dioxide (Tc pCO2), oxygen saturation (SaO2), palmar sweat, intracranial pressure (ICP) and vagal tone. In newborn populations, heart rate is the most frequently studied physiological indicator (Sweet 1998). Behavioral indicators include facial expression, cry, gross motor movement, and changes in behavioral state. Facial expression (Grunau 1987) is the most comprehensively studied behavioral indicator for neonatal pain.

Multidimensional measurement tools that employ more than one parameter usually contain physiological and behavioral indicators, and occasionally add contextual information to obtain an overall pain score. The Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS) (Lawrence 1993) and the Premature Infant Pain Profile (PIPP) (Stevens 1996) are multidimensional tools frequently utilized as outcome measures for investigation of acute procedural pain in term and preterm neonates. Although a number of pain measures are available for use with neonatal populations, no single measure has proven to be the best for all situations. Accordingly, all outcomes evaluated in the included studies as measures of neonatal pain were included in this review.

SUMMARY

The substantial amount of research conducted to date suggests a willingness to address the problem of circumcision pain. However, the majority of neonates are circumcised without interventions for pain (Myron 1991; Ryan 1994; Snellman 1995; Wellington 1993). This situation persists despite growing awareness that newborns may perceive pain more intensely than older children or adults (Anand 2001; Fitzgerald 1993) and can be significantly compromised by it.

It has been suggested that training to manage circumcision pain is inadequate to promote consistent use of available interventions (Howard 1998). Recent surveys indicate that significant numbers of obstetricians (75%), family practitioners (44%), and pediatricians (29%) do not use analgesia/anaesthesia for circumcision because of concerns about adverse drug effects or because they believe that the procedure does not require pain management (Maxwell 1999; Stang 1991; Stang 1998).

Although a wide variety of interventions for circumcision pain have been examined, the individual and relative effectiveness of each has not been systematically assessed. Thus, the apparent reluctance of practitioners to adopt the regular use of pain interventions for circumcision may reflect beliefs that the findings of research conducted to date are collectively un‐interpretable. At the same time, negative perceptions of the technical and practical difficulties associated with pain interventions may diminish clinician motivation to implement their regular use.

A systematic review of the research in this area was needed to summarize and identify implications arising from the existing evidence, and to provide an informed basis for practice and to identify gaps in knowledge which require further investigation. This review adds to knowledge gained from a previous systematic review which examined the efficacy of a single intervention for circumcision pain (Taddio 2002) by evaluating the efficacy and safety of all interventions for reducing pain at neonatal circumcision.

Objectives

To determine the safety and effectiveness of interventions to relieve pain associated with neonatal circumcision. Subgroup analyses were prespecified according to wait time (after anaesthetic administration and prior to start of surgery) for penile blocks, and for dose delivered for sucrose interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Studies reported only as abstracts were included if relevant.

Types of participants

Male term or preterm neonates undergoing circumcision during the neonatal period (with postnatal age maximum of 28 days after reaching 40 weeks corrected gestational age).

Types of interventions

Any intervention intended to relieve pain during the circumcision procedure, for example, penile blocks, topical anaesthetics, oral sucrose administration, oral analgesics, surgical devices or techniques, or environmental manipulation such as music therapy or special restraints. This review included trials of interventions for circumcision pain in which any intervention was compared with placebo, no treatment, or with another active intervention.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome was pain as assessed by:

1. Physiological variables, such as heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), oxygen saturation, or blood pressure (whether reported as change in, mean or absolute values) 2. Biochemical variables, such as salivary or serum cortisol levels (whether reported as pre‐ and post‐ measures or as change from baseline values) 3. Cry variables, for example, latency and duration of first cry, total cry duration, and/or percentage of time crying during the circumcision procedure 4. Validated pain measures, for example: ‐ Neonatal Infant Pain Score (Lawrence 1993); ‐ Neonatal Facial Action Coding System (Grunau 1987); ‐ Premature Infant Pain Profile (Stevens 1996); ‐ Other pain measures.

Secondary outcomes:

Complications of pain interventions were assessed as secondary outcomes. The outcomes included but were not limited to: 1) occurrence/incidence of methaemoglobinaemia (topical anaesthesia) 2) blanching and local skin irritations (topical anaesthesia) 3) bleeding, bruising and hematoma formation (penile blocks) 4) behavioral responses such a choking, spitting up, etc. during circumcision (all interventions)

Difficulties encountered in implementation of pain interventions, as reported by researchers, were noted.

Search methods for identification of studies

Standard methods as per the guidelines of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group (CNRG) were utilized. 1. CIRCUMCISION/exp 2. circumcision surgery.mp 3. newborn circumcision.mp 4. 1 OR 2 OR 3 5. local anaesthes* 6. penile block.mp/exp 7. dorsal penile nerve block.mp/exp 8. ring block.mp/exp 9. 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 10. eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics.mp/exp 11. EMLA.mp/exp 12. LIDOCAINE.mp/exp 13. 10 OR 11 OR 12 14. acetaminophen.mp/ OR paracetamol.mp/exp 15. sucrose.mp 16. pacifiers.mp 17. music therapy.mp 18. Gomco clamp.mp 19. Mogen clamp.mp 20. 9 OR 13 OR 14 OR 15 OR 16 OR 17 OR 18 OR 19 21. 4 AND 20 22. HUMAN 23. MALE 24. 22 and 23 25. infant, newborn 26. neonat* 27. 25 OR 26 28. 24 AND 27 29. 21 AND 28 30. clinical trial 31. 29 AND 30

Databases searched included: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2004; MEDLINE 1966 ‐ April 2004; EMBASE 1988 ‐ 2004 week 19; CINAHL 1982 ‐ May week 1 2004; PubMed 1966 ‐ May 2004; Web of Science 1975 ‐ May 2004; Dissertation Abstracts 1986 ‐ May 2004. Keywords and (MeSH) terms included infant/newborn, male, circumcision, penile blocks, sucrose, lidocaine, EMLA, acetaminophen. Abstracts of the World Congress on Pain were searched for the years 1993 ‐ 1999 inclusive. Reference lists of all articles were screened to identify any additional studies. Language restrictions were not imposed.

Data collection and analysis

Study Selection

The titles and abstracts of all reports identified through the electronic and other searches were scanned independently by two reviewers and full study reports were obtained for those that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. Study reports were then evaluated independently by two reviewers for possible inclusion in the review. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Studies rejected at this stage were included in the Table of Excluded Studies. Quality Assessment

Assessment of the quality of all included studies was undertaken independently by two reviewers as a component of the data extraction process. Standard methods of the CNRG were used to assess: 1) the randomisation procedure, 2) concealment of allocation/blinding of randomisation, 3) blinding of intervention, 4) subject attrition and follow‐up, and 5) blinding of outcome measurement. As per the CNRG guidelines, an overall quality score was not assigned. Reviewers were not blind to trial authors or institutions during the study selection or quality assessment processes.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted from included studies by two independent reviewers using a data extraction form designed specifically for this review. The data extraction form was developed in a draft format and piloted on several studies and modified as required before use. The reviewers abstracted data independently, compared results and resolved differences.

Sixteen trials included in this review either did not report outcome data, or did not report data in a format that could be analysed in this review (Arnett 1990; Benini 1993; Blass 1991 A; Holliday 1999; Holve 1983, Joyce 2001; Kass 2001; Marchette 1989; Marchette 1991; Maxwell 1987; Mohan 1998; Mudge 1989; Spencer 1992; Williamson 1997; Zahorodny 1998; Zahorodny 1999). Additional information was sought from ten authors and means and standard deviations were subsequently obtained for three trials (Benini 1993; Joyce 2001; Kass 2001). Where means and standard deviations were not available, data were imputed or derived from graphs contained in the reports (Arnett 1990; Benini 1993; Blass 1991 A; Holliday 1999; Maxwell 1987; Mohan 1998; Mudge 1989; Taddio 1997). Missing standard deviations were either calculated from other summary statistics or imputed using singular or mean standard deviations from similar trials.

Several authors reported total sample size only and information about the number of subjects per group was obtained from the authors (Benini 1993; Joyce 2001). When additional information about sample size could not be obtained from the authors, we assumed equal distribution to study groups in our data analyses (Blass 1991 A; Zahorodny 1998; Zahorodny 1999).

Data Analysis

The outcomes presented in this review were reported as results obtained during the whole circumcision procedure. Usually, the circumcision surgery was described as commencing with application of forceps to the dorsal foreskin of the penis (referred to as dorsal or lateral clamping) and ending with removal of the surgical clamp (the Gomco, Mogen, or Plastibell surgical device, also referred to as a clamp). Some authors reported a single numerical outcome result for the entire circumcision procedure (e.g. Butler O'Hara 1998; Howard 1999; Maxwell 1987; Taddio 1997). Others reported numerical results by procedure phase or step (e.g. dorsal foreskin grasped with forceps, adhesion lysis, dorsal incision, surgical clamp application, foreskin amputation, surgical clamp removal) (Benini 1993; Lander 1997; Woodman 1999). For the latter studies, depending on the outcome, we calculated either the arithmetic mean (e.g. heart rate) or total (e.g. time crying) across the phases or steps of the circumcision (as defined by the authors), and did not include the baseline or recovery phase data. Variance formulae for these arithmetic means and these totals were derived according to the general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)). We assumed a correlation of 0.5 as proposed by Follmann 1992. Additional Tables 1 ‐ 7 (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7) provide specific details on summary estimate extractions from the included studies.

1. Trials assessing pain/behavior scores.

| Study ID | scale | measurement method | data reported | data preparation |

| Arnett 1990 | infant irritability irritabilify graded subjectively on a scale of 1 to 6 with 1 representing the least crying/agitation and 6 the most | nurse and physician rating of infant irritability graded before, during and 1 hour after circumsion | mean/SD of assessment during procedure | data entered into meta‐analysis as reported |

| Benini 1993 | Neonatal Facial Action Coding System (Grunau , 1990b) 10 facial actions scored, 7 (brow bulge, eye squeeze, nasolabial furrow, open mouth, vertical stretching of mouth, horizontal stretching of mouth, taut tongue) entered into analysis | facial actions videotaped continuously, second by analysis of facial actions 10 facial actions scored, 7 facial actions entered into analysis total score computed by summing 7 categories | outcome data (means/SDs) obtained from authors | calculate arithmetic mean of scores across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) "procedure" = [application of dorsal clamp, incision, adhesion lysis, Gomco clamp on, foreskin excision, Gomco clamp off, restraints removed] |

| Butler‐O'Hara 1998 | Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS) consists fo 6 behavioral components with a composite score of 0 to 6 5 components used ‐ facial expression, cry, breathing pattern, arm movements, state of arousal (Lawrence, 1993) | procedure videotaped NIPS scores assigned for each of 6 events (clamping of foreskin, adhesion lysis, dorsal cut, adhesion lysis, tying of Plastibell, foreskin excision) mean NIPS score calculated for each infant | mean(SD) NIPS score/group | data entered into meta‐analysis as reported |

| Dixon 1984 (Holve 1983 is primary study report) | Brazelton Neonatal Assessment Scale (BNAS) consists of 27 behavioral items, each scored on scale of 1 to 9, and 20 reflexes scored on 3 point scale scale examines organization and integration of behavior in response to positive and adversive situations | examinations conducted prior to (exam 1), following the circumcision (exam 2), and 1 day after circumcision (exam 3) | mean scores/item for 3 exam times | states "variation in item scores precluded determination of statistically significant differences between groups' not included in meta‐analysis |

| Hardwick‐Smith 1998 | behavioral state (Stang et al 1988) score 1 ‐ 6 in order of increasing arousal | scored at baseline, 10 intervals during procedure, and 2 hr post‐circumcision | p values | not included in meta‐analysis |

| Holliday 1999 | behavioral scale ‐ includes 8 behavior state variables (sleep state, cry, facial expression, torso movement, soothability, response to distress, need for tactile stimulation, environmental noise) each variable scored 1 to 6, scores totaled for each infant | assessed 20 min before, during and after circumcision | means scores/group reported in graph format | graph extractions to obtain mean/SD |

| Howard 1994 | Postoperative Comfort Score (Attia 1987) 10 behaviors, each scored 0, 1, or 2, possible scores 0 to 20, lower score = less comfortable | assessed baseline, and postcircumcision at 30, 60, 90, 120, 360 min | mean/SD scores/group/interval mean/SD change from baseline scores/group/interval | data entered into meta‐analysis as reported for 30 min post‐circumcision scores |

| Howard 1999 | behavioral distress scale (from Stang et al 1997) score 0 ‐ 3 based on Brazelton statte assessment score 0 = neutral to 3 = sustained cry | videotape of procedure assessed and scores assigned every 30 s of the procedure | mean/SE scores / group for stages 2 to 6 of procedure | data entered into meta‐analysis as reported "procedure" = [block administration to recovery; includes 4 min WT and Gomco clamp left on for 5 min] |

| Joyce 2001 | Riley Infant Pain Scale 6 categories of behavior (vocal, facial expression, body movement, sleep, consolability, response to touch) rates on scale of 0 (no pain) to 3 (severe pain) | videotape of procedure assessed at baseline, undressing, restraints, cleanse, clamping, cutting, end of procedure, 15 min post and 30 min post | RIPS score / group / phase presented in graphic format p values | not included in meta‐analysis |

| Kass 2001 | MBPS ‐ modified behavioral pain scale (Taddio et al, 1995) rates facial expression, crying, and body movements to obtain a score of 0 to 10 | scored at 30 s intervals | mean/SD for baseline and procedure MBPS / group obtained from authors | mean/SD procedure scores entered into meta‐analysis |

| Macke 2001 | Nursing Child Assessment Feeding Scale (NCAFS) 76 behavioral binary items (yes,no) grouped into 6 subscales based on concepts of adaptation and synchronism | scored during feeding interaction before and after circumcision | mean/SD score pre/post circumcision | data included as reported |

| Newton 1999 | Brazelton Neonatal Assessment Scale ‐ scale categorized to 6 level\s ‐ (deep sleep (1), light sleep (2) drowsy (3), quiet alert (4) active alert (5) crying (6) (Brazelton, 1984) | 3 evaluations ‐ baseline, injection, clamp application | modal state/group | data not included |

| Stang 1988 | behavioral state 6 levels = quiet sleep (1), active sleep (2), drowsy (3), alert (4), active awake (5), crying (6) (Brazelton, 1973) | assessed at baseline, during injection, during circumcision, and 30 min from the start of the circumcision | modal response / group / time period | data not included |

| Stang 1997 | behavioral state scale and behavioral distress scale 4 levels ‐ neutral (0), minimal fuss (1), moderate fuss (2), sustained cry (3) (Brazelton, 1973) | behavioral state and distress scored every 30 s beginning 2 min before circumcision scores averaged for 5 periods ‐ preinjection, injection, 2 min post‐injection, 4 min post‐injection, circumcision | mean/SD /group / study period | mean/SD for circumcision period included |

| Taddio 1997 | Neonatal Facial Coding System (Grunau et al, 1987; 1990) codes presence or absence of 10 discrete facial actions (brow bulge, eye squeeze, nasolabial furrow, open mouth, vertical stretching of mouth, horizontal stretching of mouth, lip pursing, taut tongue, chin quiver, tongue protrusion) higher score = more pain | facial actions continuously recorded on videotape facial actions scored from videotape in 2 s intervals for first 20 s of each phase raw scores of each facial action expressed as proportion of time observed/phase; poorly correlated facial actions deleted leaving 6 facial actions; the six scores were weighted and totaled to arrive at overal score for facial action | mean/95% confidence intervals for facial activity score / group / 13 phases reported in graph format data extracted from graphs | data extraction to obtain mean/SD facial score for circumcision phases circumcision (7 phases) = [application of forceps to foreskin excision] calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of circumcision calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) SE = ((high CI ‐ low CI)/2)/1.96 SD = SE (sqrt(n)) |

| Weatherstone 1993 | newborn pain behavior scale adapted from 3 other scales (Brazelton 1973; Yarrow 1975; Ross 1988) score includes assessment of behavioral state, leg and arm movement, facial expression, torso movement, respiratory pattern, soothability, response to distress by caregivers, tactile stimulation | videotape of procedure scored in 30 s intervals | increase in mean/SD % of time behavior observed post‐cirucmcision compared to pre‐ circumcision/group | data not included |

2. Trials assessing heart rate outcome variables.

| Study ID | measurement method | data reported | preparation of data |

| Arnett 1990 | HR measured by pulse oximetry at baseline, every min for 4 min, and 5 min post‐circumcision | mean HR/group/phase reported in graph format | graph extraction for means graph extraction for SDs (averaged over 4 phases of the circumcision procedure) "procedure" = [min 1 to min 4]; steps not described or standardized |

| Benini 1993 | HR measured continuously by pulse oximeter | outcome data (mean/SDs) obtained from authors | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) "procedure" = [application of dorsal clamp, incision, adhesion lysis, Gomco clamp on, foreskin excision, Gomco clamp off, restraints removed] |

| Butler‐O'Hara 1998 | HR monitored continuously using cardiac monitor | mean/SD heart rate (bpm) at completion of circumcision by group mean/SD heart rate (bpm) change from baseline at completion of circumcision by group | data entered into meta‐analysis as reported |

| Joyce 2001 | HR monitored continuously using cardiac monitor | data (bpm) obtained from authors | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) "procedure" = [cut, end of procedure] |

| Hardwick‐Smith 1998 | HR monitored continuously using cardiac monitor highest HR recorded at start of each interval | increase in HR from baseline per group for operative interval reported in graph format | graphs did not depict SDs (whiskers); researchers reported control infants had signifcantly greater increase over baseline during 7 out 10 operative intervals; they did not comment on differences between the groups/interval |

| Herschel 1998 | HR monitored continuously using cardiac monitor | mean/SD HR (bpm) change from baseline during procedure by group | data entered into meta‐analysis as reported "procedure" = lateral clamp of foreskin to foreskin excision |

| Holliday 1999 | HR monitored continuously using cardiac monitor HR recorded every 5 min before, during, 5 and 20 min after circumcision | mean/SD HR (bpm)/group reported in graph format for 4 time points (before, during, 5 min after, 20 min after) | graph extraction to obtain mean/SD during procedure |

| Holve 1983 | HR continuously recorded using monitor | mean change in HR from baseline (bpm) weighted averages/group for 6 phases reported in graphic format | no SDs, SEs depicted on graphs |

| Howard 1994 | HR counted via auscultation every 30 s | mean/SD HR (bpm) / group / phase mean/SD HR (bpm) change from baseline by group/phase | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) "procedure" = [dissection, clamp on, excision, clamp off] |

| Howard 1999 | HR recorded every 60 s using cardiac monitor | ‐ mean/SE HR (bpm) during procedure by group | means included as reported convert SE to SD using formula: SD = SE (sqrt (n)) "procedure" = [block administration to recovery; includes 4 min WT and Gomco clamp left on for 5 min] |

| Kass 2001 | HR monitored at 1 min intervals during procedure | mean/SD HR (bpm) during procedure by group obtained from authors | mean/SD entered into meta‐analysis |

| Kurtis 1999 | HR monitored continuously using cardiac monitor | mean/SD % HR change from baseline during procedure by clamp used (Mogen, Gomco) and by penile block status (block, no block) | data entered into meta‐analysis as reported "procedure" = [lysing adhesions to 60 sec after closing clamp] |

| Lander 1997 | HR monitored continuously using cardiac monitor | mean/SD HR (bpm) change from baseline by phase by group | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) "procedure" = [separation, clamp on, clamp off] |

| Macke 2001 | HR recorded every 15 s using cardiac monitor | mean/SD HR (bpm) during circumcision by group | data included as reported |

| Marchette 1989 | HR monitored | mean HR /phase / group no SDs reported | not included |

| Marchette 1991 | HR monitored and data collected during 14 cirumcision steps | RMANOVA over 14 steps | not included |

| Masciello 1990 | HR monitored continuously using cardiac monitor peak HR during each step recorded | mean HR as a percent of baseline HR reported in graphic format | not included |

| Maxwell 1987 | HR monitored continuously by pulse oximeter peak HR during each period recorded | mean/SD HR change / group / period as a % of control (baseline) reported in graph format | graph extraction to obtain mean/SD during circumcision procedure |

| Mohan 1998 | HR monitored continuously by pulse oximeter HR recorded at each of 9 steps | mean HR / group / procedure step reported in graph format | graph extraction to obtain mean HR / group / procedure step substituted weighted average treatment‐specific SDs from 5 studies: Benini 1993, Joyce 2001, Lander 1997, Taddio 1997, Woodman 1999 for EMLA and from 3 studies: Herschel 1998, Kass 2001, Zolnoski 1993 for sucrose |

| Mudge 1989 | HR measured by monitor at 5 time points during circumcision | mean HR / group / event reported in graph format RMANOVA for 4 events (adhesion breakdown to clamp off) | graph extraction to obtain mean HR/group for events 2 ‐ 5 calculate arithmetic mean HR / group across 4 phases of the procedure (adhesion breakdown, clamp on, tighten clamp, clamp off) substitute SDs from Woodman 1999 who applies same outcome to same comparison |

| Newton 1999 | HR monitored continuouslly by pulse oximeter HR recorded at 10 s intervals | mean/SD HR / group at baseline, injection, clamp application | included as reported |

| Spencer 1992 | HR monitored by pulse oximeter recorded highest HR for each of 6 events | mean change in HR (bpm) from baseline / group / event | no SDs, not included |

| Taddio 1997 | HR continuously monitored by cardiac monitor | mean/SD HR (bpm) change from baseline during procedure | data included as reported "procedure" = [forcep application, lysis of adhesions, dorsal incision, clamp application, pull foreskin through clamp, tighten clamp, cut foreskin] procedure does not include clamp removal at 5 min after cut foreskin |

| Weatherstone 1993 | HR monitored at 5 min intervals for 20 min | none | not included |

| Williamson 1983 | HR monitored continuously | mean/SD HR (bpm) change from baseline for 3 min "dissection" period | mean/SD data included as reported dissection does not include clamp application |

| Woodman 1999 | HR monitored continuously using pulse oximeter recorded peak heart rate during or immediately following 7 stages of circumcision procedure | mean/SD peak HR (bpm) / group | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) "procedure" = [clamp, adhesionlysis, dorsal clamp, bell on, clamp tightening, bell off] |

| Zolnoski 1993 | HR monitored continuously using cardiac monitor HR (bpm) recorded at beginning of 7 procedure steps | ‐ mean/SD HR (bpm) /group for 4 procedure steps | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) |

3. Trials assessing cry outcome variables.

| Study ID | measurement method | data reported | data preparation |

| Benini 1993 | cry tape recorded | % time crying/phase (duration of time crying) reported in graph format | means, SEs (assumed) extracted from graph; calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) "procedure" = [dorsal clamp, incision, lysis, clamp on, foreskin cut, clamp off, unrestrained] |

| Blass 1991 | cry tape recorded | mean % time crying (duration of time crying) during entire procedure reported in graph format | ‐ graph extraction of group mean/SE; ‐ SD calulated using formula: SD = SE (sqrt (n)) |

| Holve 1983 | cry tape recorded | mean % time crying /interval reported in graphic format | no SDs, not included |

| Hardwick‐ Smith 1998 | cry tape recorded | mean/SD minutes crying/group during operative interval (lateral clamping to clamp removal) | convert reported time to seconds data included in meta‐analysis |

| Howard 1994 | used stopwatch to time crying during each phase | mean/SD % time crying by group/phase mean/SD % time crying change from baseline/group/phase | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) "procedure" = [dissection, clamp on, excision, clamp off] |

| Joyce 2001 | behavior videotaped calculated total time crying from start of foreskin cut until crying ceased or 30 min elapsed | cry time (min) for each subject obtained from authors | calculate mean/SD time crying in min and sec/group |

| Kass 2001 | primary outcome variable behavior videotaped | mean/SD time crying (s) /group during procedure obtained from authors | mean/SD included in meta‐analysis |

| Kurtis 1999 | behavior videotaped calculated time crying using stopwatch | mean/SD % time crying during procedure reported by clamp used (Mogen, Gomco) and by penile block status (block, no block) | mean/SD included as reported |

| Lander 1997 | behavior videotaped proportion of time crying calculated/subject | mean/SD % time crying/interval | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y))‐ "procedure" = [separation, clamp on, clamp off) |

| Macke 2001 | continuous vocalizations of 15 s or more classified as crying and tape recorded total s used to calculate % time crying | mean/SD % time crying during circumcision period by group | data included as reported |

| Mohan 1998 | stopwatch used to measure duration of crying | mean % time crying / group during entire procedure | not included |

| Mudge 1989 | crying time tape recorded during procedure measured by stop watch | mean total crying time (s)/group for entire procedure t‐statistic, p value | mean crying time included as reported SD imputed from t statistic procedure includes 5 events (baseline, adhesion breakdown, clamp on, tighten clamp, clamp off) |

| Spencer 1992 | cry duration measured by modified Brazelton Neonatal behavioral Scale (Stang et al, 1988) 6 behavioral states recorded for each of 6 events | mean % change from baseline / group | no SDs, not included |

| Stang 1988 | not described | mean/SEM % time crying during circumcision period/group | means included as reported SEM converted to SD using formula: SD = SEM (sqrt (n)) |

| Taddio 1997 | behavior videotaped calculated % of time crying during each phase | mean/SD % increase from baseline in time crying during procedure | data included as reported "procedure" = [forcep application, lysis of adhesions, dorsal incision, clamp application, pull foreskin through clamp, tighten clamp, cut foreskin] does not include clamp removal at 5 min after foreskin cut |

| Williamson 1983 | time crying recorded using event marker | mean/SD % time crying change from baseline during 3 min dissection period | mean/SD data included as reported |

| Woodman 1999 | behavior videotaped recorded time crying based on facial actions with or without audible cry | mean/SD time crying (s) for 6 phases by group | add time crying for 6 of 8 stages (clamp, adhesionlysis, dorsal clamp, clamp on, clamp tightening, clamp off) to obtain total time crying during procedure add SD to obtain total SD for group |

| Zahorodny 1998 | not reported | mean % time crying/group | substituted weighted average treatment‐specific SDs from three other studies: Benini 1993, Lander 1997, Taddio 1997 for EMLA vs placebo/ no treatment substituted treatment‐specific SDs from Blass 1991 A (also versus water) for sucrose vs placebo/ no treatment substituted with the SDs used in the two above comparisons for EMLA vs sucrose |

| Zolnoski 1993 | cry tape recorded, measured using stopwatch | time cry (s)/infant | mean/SD cry time (s)/group calculated |

4. Trials assessing oxygen saturation outcome variables.

| Study ID | measurement method | data reported | data preparation |

| Arnett 1990 | measured by pulse oximetry at baseline, every min for 4 min during procedure, and 5 min postcircumcision | mean oxygen saturation (%) / group / phase and SDs presented graphically | graph extraction of means, graph extraction of SDs, averaged over 4 phases |

| Benini 1997 | O2sat continuously monitored using pulse oximeter | outcome data (mean/SD) obtained from authors | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) procedure = [application of dorsal clamp, incision, adhesion lysis, Gomco clamp on, foreskin excision, Gomco clamp off, restraints removed] |

| Hardwick‐Smith 1998 | O2sat monitored continuously by pulse oximeter, lowest O2sat recorded at the start of each interval during some intervals of procedure, O2sat not recorded in up to 50% of infants | mean/SD of O2sat (%)/group for operative intervals | data included in meta‐analysis as reported "operative interval" = [llateral clamp, blunt dissection, dorsal clamp, adhesion takedown, Gomco bell on, Gomco clamp applied, Gomco clamp removed] |

| Herschel 1998 | O2sat continuously monitored via pulse oximetry substantial proportion of data lost due to excessive motion (31% control, 10% DPNB, 8% sucrose) | mean/SD O2sat (%) change from baseline during operative procedure by group | data included in meta‐analysis as reported "operative procedure" = [lateral clamp of foreskin, adhesion lysis, dorsal clamp, dorsal cut, foreskin retraction, Gomco application, Gomco tightened, foreskin excision] |

| Holliday 1999 | O2sat continuously monitored, recorded every 5 min before, during, 5min and 20 min after circumcision | mean/SD O2sat (%)/group reported in graph format for 4 time points (before, during, 5 min after, 20 min after) | graph extraction for mean/SD during procedure |

| Joyce 2001 | O2sat monitored continuously using pulse oximeter recorded O2sat (%) at each of 6 data collection points | raw data per subject per 6 phases obtained from authors | calculate mean/SD by group/phase calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) procedure = [cut, end] |

| Kass 2001 | monitored O2sat at 1 min intervals during procedure | mean/SD O2sat during procedure by group data obtained from authors | mean/SD included in meta‐analysis |

| Kurtis 1999 | O2sat (%) monitored continuously and transferred to computer | ‐ mean/SD % change from baseline during procedure reported by clamp used (Mogen, Gomco) and by penile block status (block, no block) | data included in meta‐analysis as reported procedure = [lysing adhesions to 60 sec after closing clamp] |

| Marchette 1991 | tcpO2 monitored and recorded during 14 circumcision steps | RMANOVA over 14 steps | not included |

| Masciello 1990 | O2sat monitored continuously by pulse oximeter lowest level during each interval recorded | mean O2sat / group / interval reported in graphic format | not included |

| Maxwell 1987 | O2sat monitored continuously using pulse oximeter peak value during period recorded | mean/SD O2sat /group / period reported in graph format | graph extraction to obtain mean/SD during circumcision period |

| Mohan 1998 | O2sat monitored continuously using pulse oximeter recorded at each of 9 procedure steps | mean O2sat / group / procedure step reported in graph format | graph extraction to obtain mean O2sat / group / step substituted weighted average treatment‐specific SDs from 3 trials: Benini 1993, Joyce 2001, Woodman 1999 for EMLA and from 2 trials: Herschel 1998, Kass 2001 for sucrose |

| Mudge 1989 | O2sat measured by pulse oximeter and recorded at five time points during circumcision | mean O2sat (%) /group/event reported in graph format | graph extraction to obtain mean O2sat/group for events 2 ‐ 5 calculate arithmetic mean O2sat / group across 4 phases of the procedure (adhesion breakdown, clamp on, tighten clamp, clamp off) |

| Spencer 1992 | O2sat monitored by pulse oximeter recorded lowest level for each of 6 events | mean O2sat % change from baseline / group / event | no SDs, not included |

| Weatherstone 1993 | O2sat monitored at 5 min intervals for 20 min | none | not included |

| Williamson 1983 | O2sat measured using transcutaneous electrode (tcpO2) | mean/SD O2sat (torr) change from baseline for 3 min dissection period | data included in meta‐analysis as reported dissection does not include clamp application |

| Woodman 1999 | O2sat monitored continuously using pulse oximeter recorded peak/nadir during or immediately following 7 stages of circumcision procedure | ‐ mean/SD peak/nadir O2sat / stage / group | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) procedure = [clamp, adhesiolysis, dorsal clamp, clamp on, clamp tightening, clamp off) |

5. Trials assessing respiratory rate outcome variables.

| Study ID | measurement method | data reported | preparation of data |

| Butler‐OHara 1998 | RR monitored continuously starting after anesthetic administration, and 1 and 4 hr after procedure | RR variable and difficult to evaluate not reported | not included in meta‐analysis |

| Hardwick‐Smith 1998 | highest RR recorded at start of each interval (anesthesia/restraint, 3 min post restraint/anesthesia, lateral clamp, blunt dissection, dorsal clamp, adhesion breakdown, Gomco bell on, Gomco clamp on, Gomco clamp removed) | mean/SD increase from baseline RR/group for operative intervals (lateral clamping to Gomco clamp removal) | data included in meta‐analysis as reported |

| Holliday 1999 | RR monitored continuously using cardiac monitor HR recorded every 5 min before, during, 5 and 20 min after circumcision | mean/SD RR (bpm)/group reported in graph format for 4 time points (before, during, 5 min after, 20 min after) | graph extraction for mean/SD during procedure |

| Howard 1994 | RR assessed by visual observation every 30 s | mean/SD RR (rpm) / group / phase mean/SD RR (rpm) change from baseline by group/phase | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) "procedure" = [dissection, clamp on, excision, clamp off] |

| Howard 1999 | RR counted and recorded every 60 s | mean/SE RR (rpm) by group for procedure | means included as reported convert SE to SD using formula: SD = SE (sqrt (n)) "procedure" = [block administration to recovery; includes 4 min WT and Gomco clamp left on for 5 min] |

| Joyce 2001 | RR monitored continuously, recorded at 6 data collection points | raw data obtained from authors | calculate arithmetic mean/group across phases of the procedure calculate variance for the arithmetic mean using general formula for linear combinations of variance (i.e. Var (X+Y) = Var(x) + Var(Y) + 2Cov(X,Y)) "procedure" = [cut, end of procedure] |

| Kurtis 1999 | RR monitored continuously using physiologic monitor | mean/SD % change from baseline during procedure reported by clamp used (Mogen, Gomco) and by penile block status (block, no block) | data entered into meta‐analysis as reported "procedure" = [lysing adhesions to 60 sec after closing clamp] |

| Mudge 1989 | RR measured by pneumography monitor at 5 time points | mean RR / group / event reported in graph format RMANOVA for 4 events (adhesion breakdown to clamp off) | graph extraction to obtain mean RR/group for events 2 ‐ 5 calculate arithmetic mean RR / group across 4 phases of the procedure (adhesion breakdown, clamp on, tighten clamp, clamp off) |

| Weatherstone 1993 | RR monitored at 5 min intervals for 20 min | none | not included |

6. Trials assessing biochemical outcome variables.

| Study ID | measurement method | data reported | data preparation |

| Masciello 1990 | blood drawn via heel stick 30 minutes post‐circumcision | mean/SD plasma cortisol levels in mg/dL | mg/dL multiplied by 27.59 = nmol/L nmol/L included in meta‐analysis |

| Stang 1988 | blood drawn via heel stick for 1/2 subjects at 30 min post‐circumcision, and 90 min for remaining 1/2 subjects | mean/SEM plasma cortisol levels in nmol/L and ug/dL | means (nmol/L) included in meta‐analysis SEM converted to SD using formula: SD = SEM (sqrt(n)) |

| Williamson 1986 | blood drawn by heel stick at baseline and 30 min post‐circumcision | mean/SEM plasma cortisol levels in ug/dL | SEM converted to SD using formula: SD = SEM (sqrt(n)) ug/dL |

| Holliday 1999 | serum B‐endorphin levels ‐ blood sample taken before and 20 min post‐circumcision | mean/SD / group in pmol/L | data included as reported |

| Joyce 2001 | salivary cortisol samples collected at baseline abd 30 min after procedure | mean/SD before/after no units of measurement results not broken down by group | not included |

| Kurtis 1999 | salivary cortisol | collected sample at baseline and 30 min post‐circumcision | mean/SD included as reported |

| Stang 1997 | plasma cortisol 30 min after beginning of circumcision | mean/SD / group nmol/dL and ug/dL | mean /SD (nmol/dL) included as reported |

| Weatherstone 1993 | serum B‐endorphin level taken pre‐operatively and 15 min after circumcision | mean/SD B‐endorphin level (pg/mL) for pre and post circumcision period/group | mean/SD level for post‐circumcision period included as reported |

| Williamson 1986 | plasma cortisol obtained at baseline and 30 min after Gomco clamp applied | mean/SEM plasma cortisol levels (ug/dL)/group | ug/dL multiplied by 27.59 = nmol/L SEM converted to SD using formula: SD = SEM (sqrt(n)) |

7. Trials assessing blood pressure outcome variables.

| Study ID | measurement method | data reported | data preparation |

| Holliday 1999 | systolic BP monitored continuously using cardiac monitor HR recorded every 5 min before, during, 5 and 20 min after circumcision | mean/SD BP (mmHg)/group reported in graph format for 4 time points (before, during, 5 min after, 20 min after) | graph extraction for mean/SD during procedure |

| Marchette 1991 | systolic and diastolic BP monitored and recorded during 14 steps of the cirumcision procedure | RMANOVA over 14 steps | not included |

| Maxwell 1987 | BP measured by Doppler every 5 min | mean/SD systolic BP change as a % of control / group / period reported in graph format | graph extraction to obtain mean/SD during circumcision period |

| Mohan 1998 | systolic and diastolic BP measured over upper arm at each of 9 procedural steps | mean systolic and diastolic BP (mm Hg) reported in graph format | graph extraction to obtain mean / group / step substituted treatment‐specific SDs from Taddio 1997 for EMLA; no SDs available for sucrose |

| Taddio 1997 | systolic and diastolic BP measured at baseline and during lysis of adhesions | mean/SD increase mm Hg in systolic and diastolic BP | data included as reported |

| Weatherstone 1993 | BP monitored at 5 min intervals for 20 min | none | not included |

Data were analysed using the statistical package (RevMan 4.2) provided by the Cochrane Collaboration. When two or more studies were identified that examined the same comparison and clinically similar outcomes, data were pooled using fixed effects. Random effects accounting for inter‐study heterogeneity were considered in sensitivity analyses. Studies that compared an active intervention with placebo were analysed separately from those that compared the same active intervention with no treatment.

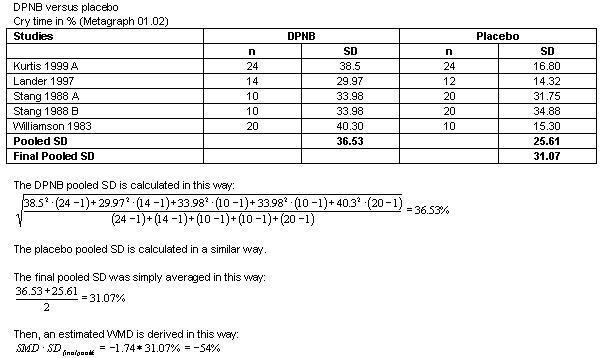

Continuous data summaries are reported as weighted mean differences (WMD) when the units provided were compatible. When the units were not compatible, the standardized mean difference (SMD) is reported. The SMD describes the difference between the treatments in terms of units of standard deviations (SDs). To improve interpretability, we also report estimates of WMDs derived from the estimated SMDs. To derive the WMDs from the SMDs, we selected either the unit used in the majority of the trials or the most clinically relevant unit under a particular comparison and pooled the available SDs from the trials that used that unit. We then multiplied this pooled SD by the SMD to obtain an estimate of the WMD. The WMDs thus derived are reported along side the SMDs in the results. An example of how a SMD was converted to a WMD is provided in Figure 1.

1.

Individual study outcomes were reported as both final values (FVs) and change from baseline values (CVs). It is appropriate to combine FVs and CVs when combining mean differences to calculate a WMD. However, it is not appropriate, generally, to combine FVs and CVs when combining SMD to calculate an overall SMD. CVs often have smaller standard errors (SEs) than FVs since some of the intra‐patient variation is removed from their SEs. Thus the individual study CV SMD tend to be in smaller SD units than the individual study FV SMD. However, in this systematic review, many of the SEs for CVs were either within the range of the FV SEs or they were larger, which is counterintuitive to the argument presented here. Hence, some of the SMD calculated in this review do combine CVs and FVs (Metagraphs 01.03; 01.08; 01.09; 03.02). Additional Tables 1 ‐ 7 (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7) provide specific details on summary estimate extractions from the included studies.

Heterogeneity was assessed quantitatively with the I‐squared statistic (Higgins 2003). The I‐squared statistic indicates the percent variability due to between study (or inter‐study) variability as opposed to within study (or intra‐study) variability. An I‐squared greater than 50% may be considered large. Only non‐null heterogeneity statistics are presented here. Too few studies under a single comparison did not allow for any assessment of publication bias nor extensive sub‐group or sensitivity analyses. However, post‐hoc, we selected heart rate (the most frequently reported outcome) for between‐study subgroup analyses using a chi‐square method proposed by Deeks 2001. We selected the following subgroup analyses a priori: for penile block interventions, "wait time" from anaesthesia administration to start of the circumcision procedure were considered by the following three categories: no wait time reported, wait time </= 5 minutes, wait time >/= 5 minutes; for sucrose administration interventions, dose of sucrose administered was to be considered but could not be due to the lack of information provided in the reports. Surgical clamp type, use of pacifiers as a co‐intervention, and choice of control group were selected for consideration post‐hoc.

Results

Description of studies

210 unique references were identified through search of the electronic databases. The full text of forty‐two potentially relevant articles were obtained and reviewed for possible inclusion in this review. Six studies were excluded (see Table ‐ Characteristics of Excluded Studies). In two excluded studies, subjects were not randomised and the intervention was chosen by the attending physician (Malnory 2003; Olson 1998). Two of the excluded studies had no comparison group (Mintz 1989, Russell 1996). One study was a cohort design and the outcome data for the control group was obtained from a previously conducted trial (Taddio 2000), and one (Taeusch 2002) was a head to head comparison of surgical clamps used for the circumcision procedure rather than a direct comparison of interventions for pain relief.

Thirty‐five studies (thirty‐six reports) were included in this systematic review. Details of each are given in the Table ‐ Characteristics of Included Studies. Two reports outlined different outcome data from the same trial (Dixon 1984, Holve 1983). Two trials were reported as abstracts only (Zahorodny 1998, Zahorodny 1999) and we were unable to obtain additional information from the authors. One unpublished report of Master's thesis research was included (Zolnoski 1993).

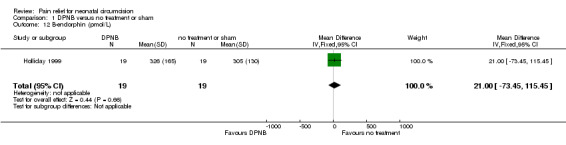

Thirty‐three of the thirty‐five included studies enrolled healthy, full term neonates. One trial included infants born preterm (and less than 28 days age after reaching 40 weeks corrected gestational age) who were ready for discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at the time of circumcision (Butler O'Hara 1998), and one trial enrolled infants born preterm and weighing 1600 ‐ 2500g at the time of circumcision (Holliday 1999).

Nineteen trials examined the effectiveness of penile blocks (Arnett 1990; Butler O'Hara 1998; Hardwick Smith 1998; Herschel 1998; Holliday 1999; Holve 1983; Howard 1999; Kass 2001; Kurtis 1999 A; Lander 1997; Masciello 1990; Maxwell 1987; Newton 1999; Spencer 1992; Stang 1988 A; Stang 1997; Williamson 1983; Williamson 1986; Williamson 1997). Twelve trials assessed topical anaesthetics (EMLA, lidocaine creams) (Benini 1993; Butler O'Hara 1998; Holliday 1999; Howard 1999; Joyce 2001; Lander 1997; Mohan 1998; Mudge 1989; Taddio 1997; Weatherstone 1993; Woodman 1999; Zahorodny 1998), and nine evaluated oral sucrose in a variety of concentrations and doses (Blass 1991 A; Herschel 1998; Kass 2001; Kaufman 2002; Mohan 1998; Stang 1997; Zahorodny 1998; Zahorodny 1999; Zolnoski 1993). In two trials, subjects received an oral analgesic (acetaminophen) (Howard 1994; Macke 2001). Three trials evaluated forms of environmental manipulation (e.g. music, intrauterine sounds) (Joyce 2001; Marchette 1989; Marchette 1991). For trial details see Table ‐ Characteristics of Included Studies.

In the trials, the interventions were compared with placebo/sham treatments (e.g. saline penile block or inactive topical cream), no treatment, or with other active interventions. In several trials, all subjects received an active baseline intervention (e.g. EMLA cream or DPNB) prior to administration of the study intervention (Butler O'Hara 1998; Kaufman 2002; Stang 1997).

Risk of bias in included studies

All of the studies included in this systematic review were described as RCTs. However, fifteen of the study reports provided insufficient information or described inadequate procedures for assurance of blinding of randomisation (see Table ‐ Characteristics of Included Studies). Nine were double‐blind for delivery of all interventions (Howard 1994; Howard 1999; Joyce 2001; Macke 2001; Mudge 1989; Taddio 1997; Weatherstone 1993; Woodman 1999; Zolnoski 1993). Some studies compared interventions which could not be masked, for example, block techniques (Masciello 1990; Newton 1999; Spencer 1992). Partial blinding was achieved in several trials through inclusion of a sham or placebo group (Arnett 1990; Blass 1991 A; Holve 1983; Kass 2001; Kaufman 2002; Lander 1997; Stang 1988 A; Stang 1997). Blinding was occasionally achieved on a temporary basis during baseline assessments (Butler O'Hara 1998; Holliday 1999). There was considerable methodologic diversity between the included studies. For example, there was variation between all of the trials as to what constituted the circumcision "procedure". In one trial (Williamson 1983), outcome data were reported for an undefined three minute "dissection period". In other trials, data were reported for each of multiple steps of a standardized procedure (Benini 1993; Hardwick Smith 1998; Herschel 1998; Lander 1997; Woodman 1999), or reported as a single summary statistic for the entire procedure (Taddio 1997). Other authors did not describe any details of the circumcision procedure followed for the trial (Blass 1991 A; Holliday 1999; Maxwell 1987; Stang 1988 A; Weatherstone 1993). In general, not enough information was provided by authors to be certain that outcome results were directly comparable across studies, as the events that constituted the procedure may not have been equivalent.

There were differences within the group of trials of DPNB (the most frequently studied intervention) in length of time fasting prior to surgery, anaesthetic dose, wait time after anaesthetic administration, and in type of surgical clamp used. In some cases, a single operator performed all circumcisions (Butler O'Hara 1998; Hardwick Smith 1998; Howard 1994), in others, the circumcisions were performed by a number of different operators (Howard 1999; Macke 2001; Stang 1997). Differences in operator technique or in the circumcision procedure could have effected outcome results. For most of the trials, subjects were required to fast prior to the surgery, however, the fasting period varied between trials from 30 ‐ 90 minutes (Arnett 1990; Blass 1991 A; Herschel 1998; Kurtis 1999 A; Maxwell 1987) to 2 ‐ 4 hours (Butler O'Hara 1998; Howard 1994; Kaufman 2002; Masciello 1990). Hunger could have influenced outcomes such as duration of infant crying or other behavioral responses. In a number of studies, subjects were offered pacifiers (Holliday 1999; Howard 1994; Howard 1999; Kurtis 1999 A; Mohan 1998; Spencer 1992; Stang 1997) although pacifiers were not the study intervention. In one trial, all subjects were offered sugar pacifiers (Butler O'Hara 1998). The potential effect of NNS on the outcomes measured in the trials providing pacifiers was not addressed in the reports.

Effects of interventions

ACTIVE VERSUS PLACEBO OR NO TREATMENT COMPARISONS

Penile block interventions

Dorsal penile nerve block

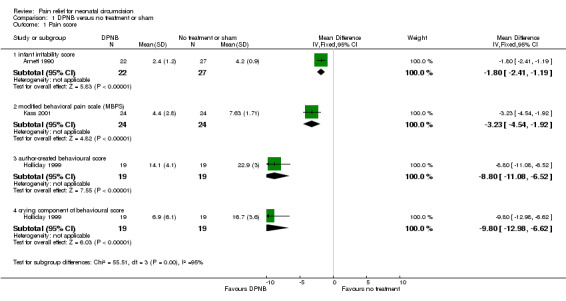

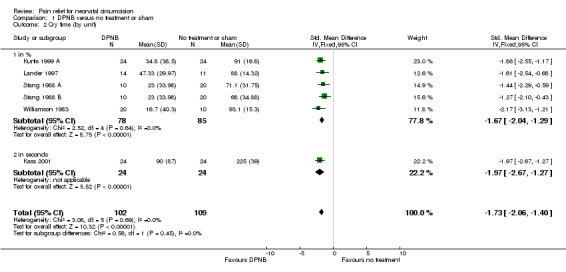

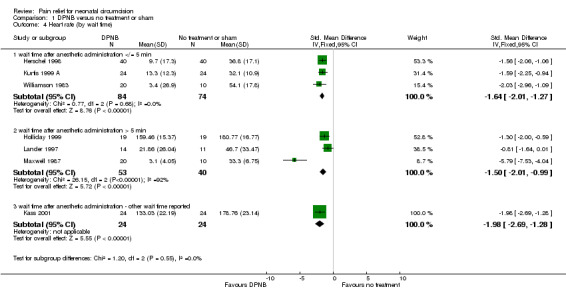

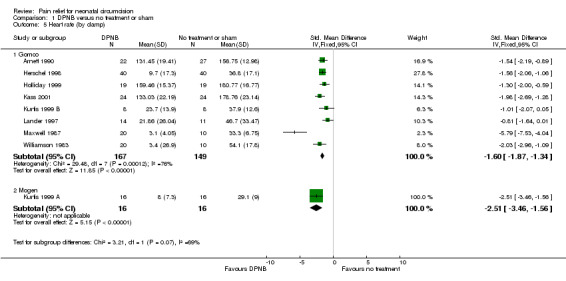

Fourteen trials compared dorsal penile nerve block (DPNB) to no treatment or placebo (sham injection). A total of 592 infants were included. Three trials employed pain scores (Metagraph 01.01) as an outcome measure (Arnett 1990; Holliday 1999; Kass 2001). These trials were not combined for meta‐analysis of effect on pain because the scores used are not similar in conceptual development or measurement technique. However, outcomes significantly favoured DPNB using all four scores reported: infant irritability score [MD ‐1.8, 95% CI ‐2.4 to ‐1.2], modified behavioral pain scale (MBPS) [MD ‐3.2 , 95% CI ‐4.5 to ‐1.9], Holliday's behaviour score [MD ‐8.8, 95% CI ‐11.1 to ‐6.5], and the crying component of the same behavioral score [MD ‐9.8, 95% CI ‐13 to ‐6.6]. Another behavioral measure, time crying, also significantly favoured the DPNB group [WMD ‐54 %, 95% CI ‐64 to ‐44; SMD ‐1.74, 95% CI ‐2.1 to ‐1.4; Metagraph 01.02; SMD displayed, WMD derived from SMD; data not shown].

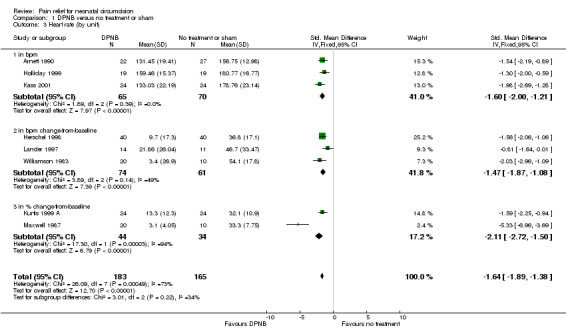

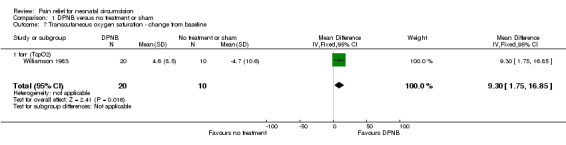

Among the physiological measures, heart rate significantly favoured DPNB [WMD ‐ 35 bpm, 95% CI ‐41 to ‐30; SMD ‐1.6, 95% CI ‐1.8 to ‐1.3; I2 = 73%; Metagraph 01.03; ; SMD displayed, WMD derived from SMD; data not shown]. Oxygen saturation results also significantly favoured DPNB [WMD 3.2 %, 95% CI 2.7 to 3.7; I2 = 97%; Metagraph 01.06]. Results were heterogeneous, and one author reported the loss of large amounts of data (Herschel 1998). A single trial (Williamson 1983) reported results for transcutaneous oxygen saturation that also significantly favoured DPNB [MD 9.3 torr, 95% CI 1.8 to 16.9; Metagraph 01.07].

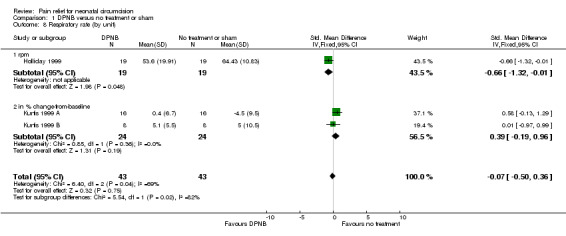

Respiratory rate (Metagraph 01.08) and serum B‐endorphin (Metagraph 01.12) were not significantly different. Systolic blood pressure was reported in two studies. The combined result was significant and favoured DPNB [WMD ‐9 mmHg, 95% CI ‐16 to ‐ 2; SMD ‐0.66, 95% CI ‐1.18 to ‐0.13; I2=92%; Metagraph 01.09; SMD displayed, WMD derived from SMD; data not shown] but the effect was not significant in the random effects model or when Maxwell 1987 was removed. The populations for these two trials were different. Maxwell 1987 recruited healthy newborns in the first few days of life, while Holliday 1999 enrolled low birthweight preterm infants. The preterm infants were cared for NICU and experience with other invasive procedures prior to circumcision may have affected their pain responses.

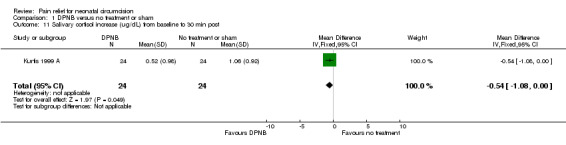

Serum cortisol (Metagraph 01.10) outcomes were reported in mg/dL, ug/dL and nmol/dL. Results were converted to nmol/dL using standard conversion factors and the outcomes expressed in these units were combined but were not significantly different. A single study (Kurtis 1999 A) reported salivary cortisol results and these were not significantly different.

In two studies (comparing DPNB to no treatment), authors did not report means and SDs. Williamson 1997 found significantly lower oxygen saturation and higher heart rates in the no treatment group during adhesion lysis and application of the surgical clamp (p< 0.001). There was a significant difference in duration of crying between the groups (p <0.001) with the DPNB group crying less. The second study found that the mean increase in heart rate and percent of time crying during circumcision was 50% less for infants in the DPNB group (p< 0.01) (Holve 1983). The DPNB group infants were more attentive to stimuli following circumcision, and were better able to quiet themselves when disturbed (Dixon 1984).

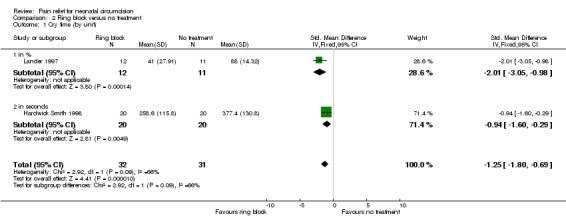

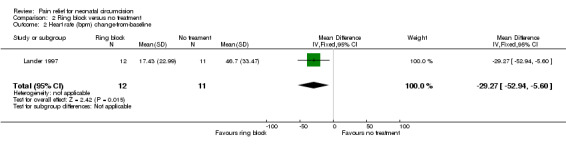

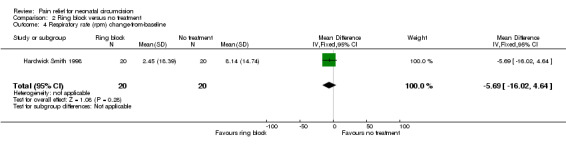

Ring block Two trials compared ring block to no treatment and included 65 subjects (Hardwick Smith 1998; Lander 1997). Percent time crying was significantly reduced in the ring block group [WMD ‐26.3%, 95% CI ‐38 to ‐15, SMD ‐1.25, 95% CI ‐1.82 to ‐0.69; I2 = 68%; Metagraph 02.01; SMD displayed, WMD derived from SMD; data not shown]. Only single studies reported other measures. In one (Lander 1997) heart rate significantly favoured the ring block group [MD ‐29 bpm, 95% CI ‐52 to ‐ 7; Metagraph 02.02]. Oxygen saturation (Metagraph 02.03) and respiratory rate (Metagraph 02.04) were reported by Hardwick Smith 1998 and were not significantly different.

Topical anaesthetics

EMLA

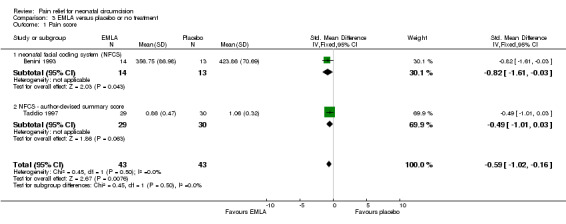

Six studies compared EMLA to placebo for a total 200 patients (Benini 1993; Joyce 2001; Lander 1997; Taddio 1997; Woodman 1999; Zahorodny 1998). Two studies measured infant behavioral responses using the same pain score, the Neonatal Facial Coding System (Grunau 1987). The trials used the same measure, but the researchers scored a different set of facial actions (see Additional Table 1), and calculated the summary pain score differently. In both summation techniques, a lower score indicated less facial action and less pain. When combined, the results significantly favoured EMLA [WMD ‐46.5, 95% CI ‐80.4 to ‐12.6; SMD ‐0.6, 95% CI ‐1.0 to ‐0.2; Metagraph 03.01; SMD displayed, WMD derived from SMD; data not shown].

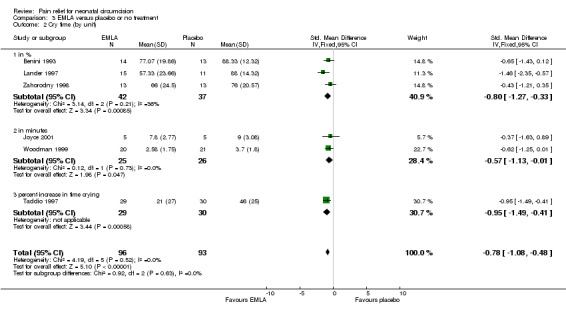

Cry time was also significantly decreased with EMLA treatment [WMD ‐ 15.2 %, 95% CI ‐21 to ‐ 9.3; SMD ‐0.78, 95% CI ‐1.08 to ‐ 0.48; Metagraph 03.02; SMD displayed, WMD derived from SMD; data not shown]. One study (Joyce 2001) did not favour the EMLA treatment, but for this study cry time was measured from the start of circumcision until crying stopped or until 30 minutes elapsed. The other studies measured cry time by phases of the procedure or gave a summary value for the procedure and thus only time spent crying during circumcision surgery could be calculated.

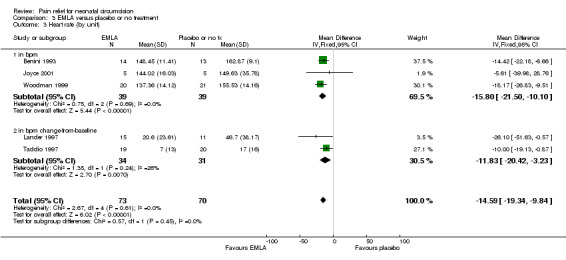

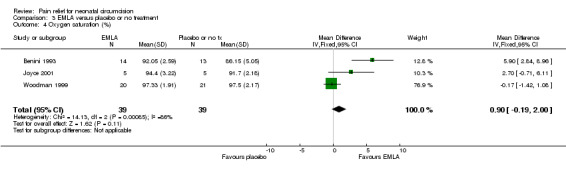

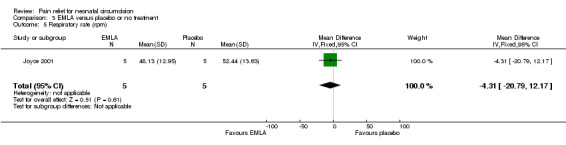

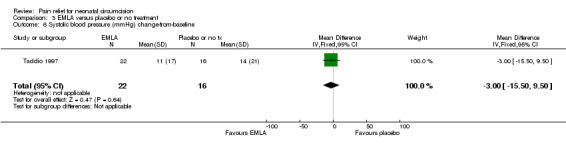

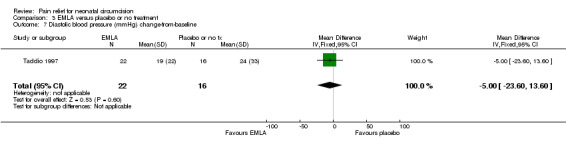

Heart rate was significantly decreased for infants treated with EMLA [WMD ‐15 bpm, 95% CI ‐19 to ‐10; Metagraph 03.03]. The effect on oxygen saturation was not significant [WMD 0.9%, 95% CI ‐0.2 to 2.0; Metagraph 03.04], and heterogeneity was large (I2= 86%). Respiratory rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Metagraphs 03.05, 03.06, 03.07) were not significantly different.

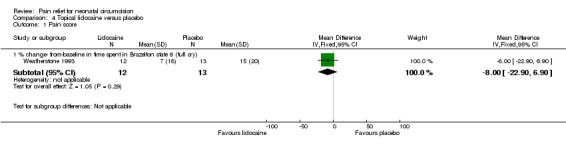

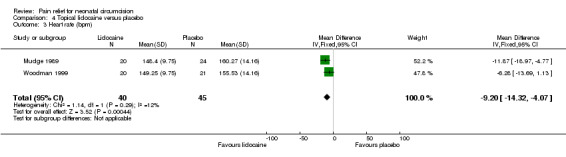

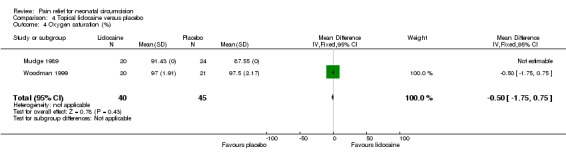

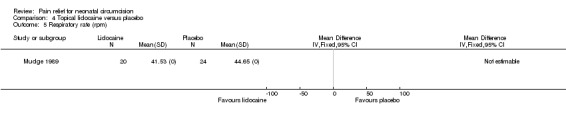

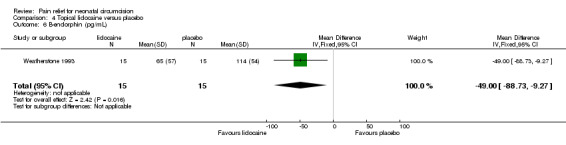

Lidocaine cream

Three trials compared topical lidocaine to placebo and included 115 patients (Mudge 1989; Weatherstone 1993; Woodman 1999). One study measured percentage of time spent in Brazelton behavioral state 6 (full cry) as a proxy for pain (Weatherstone 1993) and the results were insignificant [MD ‐8, 95% CI ‐23 to 7; Metagraph 04.01]. Cry time was significantly reduced [WMD ‐60 s, 95% CI ‐99 to ‐20; Metagraph 04.02] and favoured lidocaine. Heart rate was also significantly reduced [WMD ‐9 bpm, 95% CI ‐14 to ‐ 4; I2=12%; Metagraph 04.03]. A single study examined B‐endorphin levels, and these were significantly reduced for the group treated with lidocaine [MD ‐49 pg/mL, 95% CI ‐89 to ‐9; Metagraph 04.06]. One study (Mudge 1989) did not report standard deviations for oxygen saturation (Metagraph 04.04) and respiratory rate (Metagraph 04.05) and these could not be calculated from the information available. However, the direction of results favoured treatment with lidocaine. Oxygen saturation results for another study (Woodman 1999) were not significantly different.

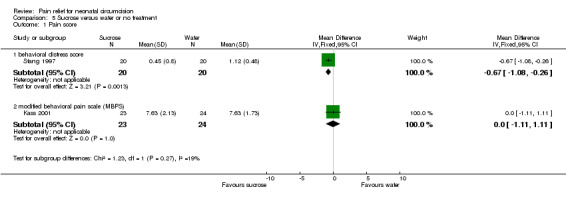

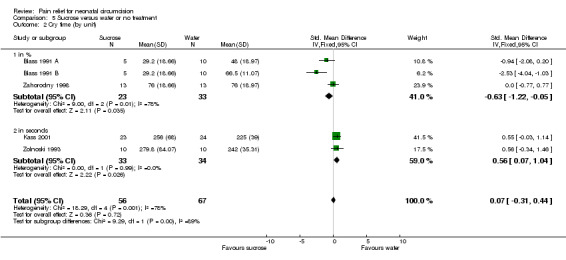

Oral sucrose/dextrose

Eight trials compared sugar solutions to water and/or no treatment and included 360 subjects (Blass 1991 A; Herschel 1998; Kass 2001; Kaufman 2002; Stang 1997; Zahorodny 1998; Zahorodny 1999; Zolnoski 1993). A variety of concentrations (24 to 50%) and volumes (1.5 to 10 ml) of sucrose or dextrose were tested. Two studies measured pain scores (Kass 2001; Stang 1997). The results were not combined because the measures are not similar in conceptual development or measurement technique. For example, distress scores (Stang 1997) ranging from 0 to 3 indicated no crying to sustained cry respectively. The modified behavioral pain scale (MBPS) scores (Kass 2001) ranged from 0 to 10 and incorporated ratings for facial expression, crying and body movements. Results using the behavioral distress score significantly favoured sucrose [MD ‐0.7 units, 95% CI ‐1.1 to ‐0.3], while the MBPS results were not significantly different (Metagraph 05.01).

Cry time results were not significantly different overall [WMD ‐ 1.3 %, 95% CI ‐5.8 to ‐8.3; SMD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.31 to 0.44; I2 = 78%; Metagraph 05.02; SMD displayed, WMD derived from SMD; data not shown]. Individual results from five trials were inconsistent in direction. Zahorodny 1998 reported means only and SDs were substituted from another study using the same intervention and same outcome measure. One study (Kaufman 2002) reported a different measure of cry time. They averaged time spent crying in 10 second intervals, then took the cumulative average of that for each group. In this study, cry time was statistically significant and favoured the sucrose group (56 vs 86 s; P=0.0001). Zahorodny 1999 did not report means or standard deviations, but did report that both the sucrose and the water group cried much less than the no treatment group (p<0.001), and that subjects receiving the sucrose pacifier cried the least (p<.03). The sucrose and water groups in this trial also had smaller increases in heart rate compared to those receiving no intervention (p<.017). These authors did not comment on any differences between the sucrose group and the water group.

The effect on heart rate was not significant [WMD ‐4 bpm, 95% CI ‐9 to 2; Metagraph 05.03] overall in three trials. Heterogeneity was large (I2=55%) with two trials favouring the water treatment and one trial favouring the sucrose treatment. In two trials (Herschel 1998; Kass 2001) oxygen saturation was significantly greater in the sucrose group [WMD 1.8%, 95% CI 0.5 to 3.1; Metagraph 05.04] although heterogeneity was again large (I2=88%) and the random effects estimate was not significant [WMD 1.3%, 95% CI ‐2.7 to 5.2]. Serum cortisol (Metagraph 05.05) was measured in a single study (Stang 1997) and results were not significant.

The inconsistent results in these trials may be related to the volume and concentration of sucrose provided and to the sucrose delivery method. For example, in two studies the treatment group received a dose of 10 ml of 50% sucrose as the treatment intervention (Herschel 1998; Zahorodny 1999), while in two other studies, the treatment group received 2 ml of 50% sucrose (Kass 2001; Zahorodny 1998). The treatment groups in the other trials received 1.5 ml (Blass 1991 A), 2.3 ml (Zolnoski 1993) or an unspecified volume of 24% sucrose (Kaufman 2002; Stang 1997) respectively. The delivery method for the sugar solution also varied between studies. Five administered the sugar/water solution via a nipple/pacifier (Blass 1991 A; Herschel 1998; Kaufman 2002; Stang 1997; Zahorodny 1999) thus providing the opportunity for non‐nutritive sucking. In one trial (Herschel 1998), the sucrose group had a nipple (and the opportunity for non‐nutritive sucking throughout the circumcision procedure), while the no treatment control group did not receive a pacifier at all. In two studies, the sugar solution was delivered using oral syringes (Kass 2001; Zolnoski 1993). In one trial, the method of delivery was not specified (Zahorodny 1998).

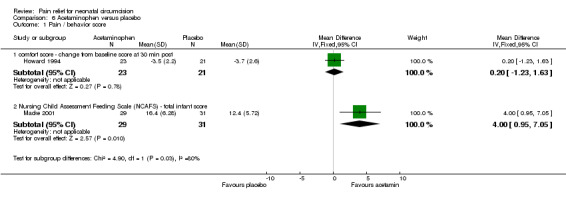

Oral analgesics

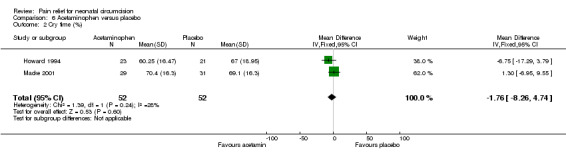

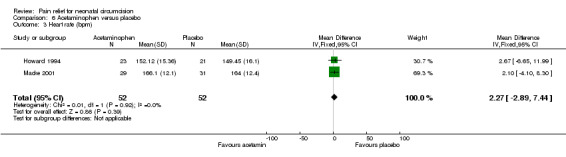

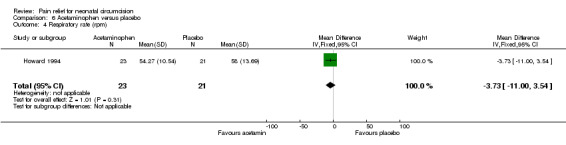

Acetaminophen