Abstract

An internal partial sequence of the gene encoding actin (ACT), 725 to 762 bp in length, was amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA extract of 12 species of dermatophytes and sequenced. An intron that is 56 to 93 bp in length was located along the ACT fragment of all of the dermatophytes at codon position 301 (−3) (a codon number followed by “−3” indicates that the intron directly follows the codon) with reference to the amino acid sequence of human α-smooth muscle actin. A primer pair that annealed to exon sequences flanking the ACT-associated intron produced a dermatophyte-specific 171-bp amplicon by reverse transcription-nested PCR (RT-PCR) of dermatophyte ACT mRNA. PCR primer pairs with antisense sequence based on the ACT intron sequence were species specific for dermatophytes, suggesting a potential for use in the identification of dermatophytes. The viability of dermatophytes in skin scales was subsequently assessed by the presence of ACT mRNA in total RNA extracted from a 48-h culture of scale samples in 250 μl of yeast carbon base broth. RT-nested PCR of dermatophyte-infected samples amplified an ACT fragment of the predicted size of 171 bp. The results of viability testing based on ACT mRNA detection by RT-nested PCR correlated with cultural isolation from skin scales. This method is a potential tool for rapidly assessing fungal viability in the therapeutic efficacy testing of antimycotics.

Dermatophytes, a group of pathogenic fungi found in the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton, belong to the family Arthrodermataceae of the ascomycetous order Onygenales. These fungi invade keratinized human and animal tissues, causing dermatophytosis, a superficial infection of worldwide distribution that accounts for the majority of superficial fungal infections.

Dermatophytosis is tentatively diagnosed by microscopic observation of septate and hyaline hyphal elements in KOH-digested skin scales. Culture isolates of dermatophytes are routinely identified by examination of colonial and microscopic morphology as well as several physiological properties. However, these procedures are usually time-consuming, and difficulties in accurate identification are sometimes encountered due to phenotypic variations among strains, thus prompting the quest for molecular diagnostic methods based on the relatively stable genotype (19). Some of the genes targeted in the molecular identification of dermatophytes include the internal transcribed spacers (ITS1 and ITS2) of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (6, 7, 8, 14, 20), the chitin synthase 1 gene (9), and the 18S rDNA (2, 10).

While diagnostic methods based on genotype provide a comparatively accurate means of identifying a pathogenic organism, the amplification of target DNA by PCR alone does not indicate the viability of the source organism, information that is of obvious importance in evaluating the efficacy of a particular therapy. On the other hand, transcription activity indicates cellular function, and the amplification of the mRNA of a particular gene by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) may be an effective molecular indicator of cell viability. Actin, a cytoskeletal protein, participates in many vital cellular functions (17, 18), and this makes the detection of transcription activity of the encoding gene (ACT) a potential indicator of cellular function in the molecular assessment of fungal viability.

In this study, an intron-containing internal fragment of dermatophyte ACT was isolated by PCR, and the sequences were analyzed. The presence of dermatophyte ACT mRNA in total RNA extract from skin scales was investigated as an indicator of the presence of viable dermatophyte cells in skin scales.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal isolates.

The isolates of dermatophytes included Microsporum audouinii (IFM 5294), Microsporum canis (IFM 47138 and 5 clinical isolates), Microsporum cookei (IFM 40904), Microsporum fulvum (IFM 5318), Microsporum gypseum (IFM 41063 and 3 clinical isolates), Microsporum nanum (CBS 728.88), Epidermophyton floccosum (ATCC 50266 and 2 clinical isolates), Trichophyton mentagrophytes (IFM 45795 and 30 clinical isolates), Trichophyton tonsurans (ATCC 44690 and 4 clinical isolates), Trichophyton rubrum (IFM 47168 and 33 clinical isolates), Trichophyton verrucosum (IFM 5278), and Trichophyton violaceum (IFM 41075). The fungal isolates with IFM accession numbers were obtained from the culture collection of the Research Center for Pathogenic Fungi and Microbial Toxicoses, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan; CBS isolates were from the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarns, The Netherlands; and ATCC isolates were from the American Type Culture Collection, Bethesda, Md. The dermatophytes were grown on Sabouraud agar (1% [wt/vol] peptone, 1% [wt/vol] glucose, 1.5% [wt/vol] agarose) at 28°C for 7 days.

Extraction of genomic DNA and total RNA from dermatophyte cultures.

Nucleic acids were isolated from cultures of dermatophytes according to the guanidinium isothiocyanate method (1) using Isogen (Wako Junyaku Kogyo, Osaka, Japan). Briefly described, 30 mg of mycelial fragments was placed in 1 ml of Isogen contained in a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube and was ground with a plastic pestle. Total RNA was then separated from genomic DNA according to the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR and RT-PCR isolation of the dermatophyte actin gene (ACT) fragment.

Since there are no reports on the nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding dermatophyte actin, the primers 5′-CGAACCGTGAGAAGATGACC-3′ (sense, bp 314 through 413) and 5′-GAACCACCGATCCAGACGGAGTA-3′ (antisense, bp 1,124 through 1,143), used for the PCR of dermatophytic ACT, were designed from the ACT of Ajellomyces capsulatus (Histoplasma capsulatum) (GenBank accession no. U17498). These primers were designed from regions of relatively high sequence homology in an alignment of the ACTs of A. capsulatus, Candida albicans (GenBank accession no. X16377), Emericella (Aspergillus) nidulans (M 22869), and Humicola grisea var. thermoidea (AB 003111). The nucleotide coordinates of primers used in this study were numbered in the 5′ to 3′ direction with reference to the coding sequence of the human α-smooth muscle actin (GenBank accession no. NM001613).

PCR was performed in a DNA thermal cycler 480 (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.) using the Takara PCR amplification kit (Takara Shuzo Co. Ltd., Shiga, Japan). The genomic DNA extracted from the dermatophyte cultures was used as templates. The 100-μl reaction mixture contained 100 ng of DNA template; 10 μl of 10× PCR buffer (Mg2+ free); 1.5 mM MgCl2; 250 μM (each) dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 20 pmol of each primer; and 5 U of Taq polymerase. A denaturation step at 94°C for 5 min was followed by 30 cycles of incubation, each consisting of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and terminal polymerization at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR product was separated in a 1.5% (wt/vol) low-melting-point agarose gel incorporating ethidium bromide and was purified from the gel using the Geneclean II kit (Bio 101, Inc., Vista, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RT-PCR of total RNA was done with the Takara RNA PCR kit (AMV), version 2.1 (Takara Shuzo), according to the manufacturer's instructions and using the PCR primers described above. The 20-μl transcription reaction mixture contained less than 1 μg of total RNA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1× RNA PCR buffer, 1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mixture, 1 U of RNase inhibitor per μl, 0.25 U of AMV reverse transcriptase per ml, and 0.125 μM oligo(dT)-adapter primer (Takara Shuzo). The mixture was incubated in the DNA thermal cycler 480 (Perkin-Elmer) at 30°C for 10 min, 50°C for 30 min, 99°C for 5 min, and 4°C for 5 min. PCR was performed in the same tube. The final 100-μl reaction mixture contained 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1× RNA PCR buffer, 2.5 U of Takara Taq polymerase per 100 μl, and 20 pmol of each primer. The RT-PCR product was separated in a 1.5% low-melting-point agarose gel incorporating ethidium bromide and was purified as described above.

Strands of purified PCR and RT-PCR products were both sequenced using the PCR primers and the dRhodamine terminator sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequence analysis was performed in the ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Perkin-Elmer), and errors and gaps in the final sequences were corrected from the overlapping sequences of both strands. The sequences were then submitted for a BLASTN homology search of DNA databases, courtesy of the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md. Dermatophyte-specific primers were then designed from an alignment of homologous regions in the ACTs of dermatophytes, A. capsulatus, and human α-smooth muscle. A BLAST search of the microbial genome databases of GenBank was then conducted with the designed primers.

Specificity of primers by RT-nested PCR.

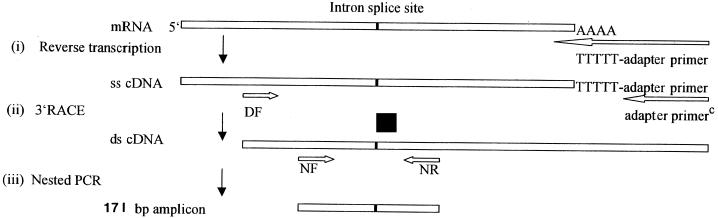

The specificity of ACT exon-based primers employed in the viability assessment was tested by reverse transcription (RT)-3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends-nested PCR (RT-3′RACE-nested PCR) (16) of total RNA extracted from human keratinocytes and cultures of the following organisms: C. albicans serotype A (JUH 3181), Candida tropicalis (ATCC 750), Candida krusei (clinical isolate), Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC 26430), Aspergillus flavus (IFO 7540), Aspergillus niger (IFO 31628), Aspergillus terreus (IFO 31675), Crytococcus neoformans (TIMM 3173), Trichosporon beigelli (clinical isolate), Trichosporon mucoides (clinical isolate), Sporothrix schenckii (clinical isolate), Nocardia asteroides (clinical isolate), Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 14970), and Streptococcus sanguis (ATCC 10556). Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of RT-3′RACE-nested PCR.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of RT-3′RACE-nested PCR showing the oligonucleotide primer locations along the dermatophyte ACT. Adapter primerC is a complement of the adapter primer.

RT reaction was performed in a thermal cycler under the conditions described above. The RT product was then amplified by 3′RACE (3) in a 100-μl reaction mixture containing 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1× RNA PCR buffer, 2.5 U of Takara Taq polymerase per 100 μl, and a 2 μM concentration of each primer. The external primers used were 5′-ATCATCTTCGAGACCTTCAACGCCCCAG-3′ (DF, bp 417 through 444) and 5′-GTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC-3′ (Takara Shuzo), a complement of the adapter sequence ligated to the 3′ end of oligo(dT)-adapter primer (Fig. 1). The amplification condition was as described for PCR except that the annealing temperature was 48°C. One microliter of 3′RACE product was then used as a template in a nested PCR employing the internal primers 5′-TATCCACGTCACCACCTACAA-3′ (NF, bp 872 through 892) and 5′-ATGATCTTGACCTTCATCGAC-3′ (NR, bp 1,020 through 1,043). The nested PCR condition was as already described but with an annealing temperature of 62°C. The RT reaction mixture of the control contained water instead of reverse transcriptase.

Specificity of primers by PCR.

The specificity of the oligonulceotide pair of DF (as described above) and an ACT intron-based antisense primer was tested by PCR of genomic DNA extract of human keratinocytes and cultures of the organisms described above. The antisense primers, whose complementary sequences are indicated in Fig. 3, were GATGCCGTAAAAGAGGAAAAGGAGACAG (E. floccosum), CATCAGTTAGTTAGTATTATTGCTAGCG (M. audouinii), GGCGAGGTGTTAGAAGGAAAAACGGTCC (M. canis), GTACGGTTATAGTATAAAGGAGGAGGAA (M. cookei), GGTCTTGTTATAGCATATAACCGTAGAA (M. fulvum), GGCTGTAGAAAGGAAAAAATGAGAAAGG (M. gypseum), GGTCTGTTATATATGGTTCACTAGCGTA (M. nanum), GTATATATACTTTAGAAGGAGAAGATAG (T. mentagrophytes and T. tonsurans), and CTATATAGTTTGTTACTGCAGAGGGAC (T. rubrum, T. verrucosum, and T. violaceum). The PCR conditions were as described above with an annealing temperature of 62°C.

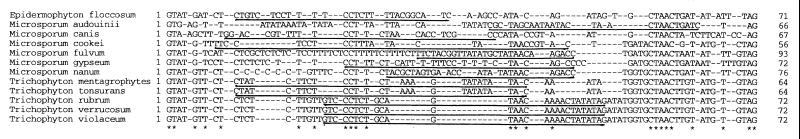

FIG. 3.

An alignment of the nucleotide sequences of dermatophyte ACT-associated introns. The species-specific oligonucleotide antisense primers are complements of the underlined sequences. A hyphen designates a gap that was added to permit alignment; an asterisk denotes a consensus base.

ACT mRNA-dependent assessment of viability of dermatophytes in skin scales.

Twenty-five samples of scales, 25 to 30 mg each, were collected from hyperkeratotic human soles. Less than 10 mg of the skin scale sample was suspended in 250 μl of yeast carbon base (YCB) broth (11.7 g/liter; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) in a 1.5-ml screw-cap Eppendorf tube. The medium contained 12.5 μg of oxacillin per ml (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and 50 μg of chloramphenicol per ml (Wako Pure Chemicals Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and was sterilized by filtration through a 0.2-μm-pore-size polysulfone membrane (Kurabo, Osaka, Japan).

The culture was incubated for 48 h at 28°C and then centrifuged for 5 min at 5,000 × g and 4°C. The precipitate was washed once in 1 ml of buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8]–1 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O–0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and suspended in 500 μl of the same buffer incorporating 20 U of RNase inhibitor (Takara Shuzo) and 500 μg of proteinase K (Sigma). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and then centrifuged for 3 min at 3,000 × g at 4°C. The precipitate was washed once in 1 ml of buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8) and 2 mM EGTA and then suspended in 1 ml of Isogen (Wako Junyako Kogyo). The precipitate was homogenized by grinding with a pestle and by several passages through a 23-gauge needle. Total RNA and genomic DNA were then extracted as described above. A 10- to 15-mg portion of the skin scale sample, without prior cultivation in yeast carbon base, was also processed for the extraction of total RNA and genomic DNA.

The total RNA extract was tested by RT-3′RACE-nested PCR, and the amplification of the expected size of dermatophyte ACT mRNA was used as an indicator of dermatophyte viability. The 18S-rDNA-based universal fungal PCR primer pair, CGAATCGCATGGCCTTG/TTCTCAGGCTCCCTCTCC (UF1/EU1), was used in the internal positive control for each sample (10). The RT-3′RACE-nested PCR condition was as described above. The annealing temperature for the internal positive control PCR was 52°C. The genomic DNA was screened by PCR using DF and a specific ACT intron-based antisense primer for the detection of T. rubrum or T. mentagrophytes. The remaining portion of the scale sample was inoculated on Sabouraud agar and incubated at 28°C.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data of the ACT fragment have been deposited in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database with the following accession numbers: AF150736 (M. audouinii), AF150737 (M. canis), AF150738 (M. cookei), AF150739 (M. fulvum), AF152228 (M. gypseum), AF152235 (M. nanum), AF152234 (E. floccosum), AF152229 (T. mentagrophytes), AF152231 (T. tonsurans), AF152230 (T. rubrum), AF152232 (T. verrucosum), and AF152233 (T. violaceum).

RESULTS

Amplification and sequence analyses of an internal partial fragment of dermatophytic ACT.

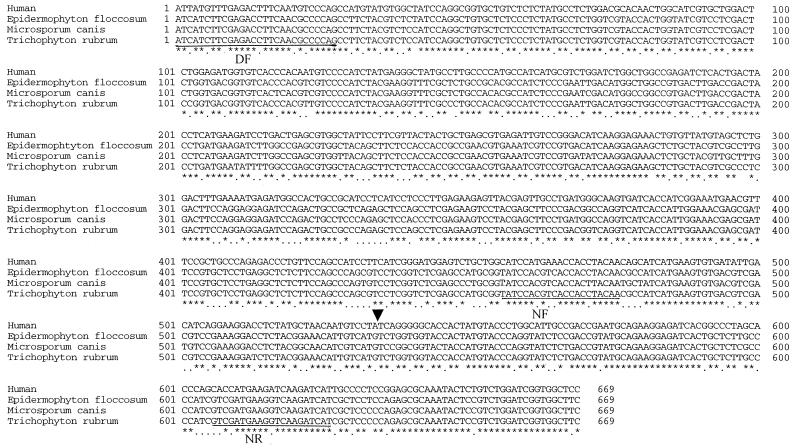

The PCR primers, which were based on the ACT of A. capsulatus, amplified a 725- to 762-bp internal partial sequence of the actin gene of 12 species of dermatophytes. The sequences had 85 to 90% nucleotide sequence homology to eukaryotic actin genes as determined by a BLASTN sequence homology search of the gene bank databases. A partial length of ACT cDNA (669 bp) was amplified by RT-PCR using the same primers as for the PCR, from the total RNA of the 12 species of dermatophytes. The sequences of the ACT exon fragment and the associated intron were species specific. An alignment of the partial ACT exon showed a high degree of sequence conservation among the dermatophytes, with a few species-specific nucleotide substitutions. Figure 2 shows an alignment of the ACT exon fragments of E. floccosum, M. canis, and T. rubrum and the homologous region of the human α-smooth muscle actin.

FIG. 2.

An alignment of ACT exon fragments of three representative species of dermatophytes and the homologous region of the human α-smooth muscle actin gene. An asterisk denotes a consensus base. The arrowhead indicates the intron splice site. The primer selection sites are underlined.

Characterization of the ACT intron sequence.

A comparative analysis of nucleotide sequences of the PCR and RT-PCR products showed a single intron located along the ACT fragment. An analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence of the partial-length ACT exon placed the ACT intron at codon position 301 (−3) with reference to the coding sequence of the human α-2 smooth muscle actin gene (GenBank NM001613) (a codon number followed by −3 indicates that the intron directly follows the codon). Figure 3 shows an alignment of the ACT intron sequences (56 to 93 bp) of different species of dermatophytes. There were no variations in intron sequences among strains of the same species of dermatophyte. The sequences of the ACT introns of T. mentagrophytes and T. tonsurans were identical; so also were those of T. rubrum, T. verrucosum, and T. violaceum. The introns showed the consensus sequences GTATG and TAG at their 5′- and 3′-splice-site junctions, respectively. The internal splice signal consensus sequence CTAAC was located variously at 8 to 12 bp upstream from the 3′-splice-site junctions of the ACT introns of different dermatophytes. No open reading frame consistent with endonuclease coding was identified in any of the introns, and no simulation of known secondary structures was found.

Primer specificity.

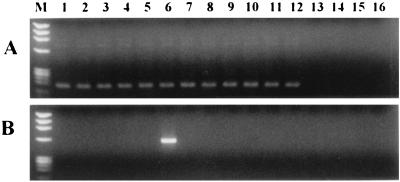

An ACT cDNA product of the expected size, 171 bp, was amplified by RT-3′RACE-nested PCR from the total RNA extract of 89 isolates of 12 dermatophyte species (Fig. 4A). No cross-amplification occurred with the human DNA or any of the reference organisms.

FIG. 4.

(A) Agarose gel images of group-specific RT-3′RACE-nested PCR-generated 171-bp ACT products of 12 species of dermatophytes and some control organisms. (B) M. canis-specific PCR product (571 bp). Lanes: M, DNA molecular weight marker IX (Roche, Mannheim, Germany); 1, T. rubrum; 2, T. verrucosum; 3, T. violaceum; 4, T. mentagrophytes; 5, T. tonsurans; 6, M. canis; 7, E. floccosum; 8, M. audouinii; 9, M. cookei; 10, M. fulvum; 11, M. gypseum; 12, M. nanum; 13, C. albicans; 14, A. fumigatus; 15, S. epidermidis; 16, human DNA. Other control organisms indicated in the text are not shown. Gel electrophoresis was done as described in Materials and Methods.

Some of the PCR primer combinations of DF and different ACT intron-based antisense oligonucleotides were dermatophyte species specific, and DNA fragments of the expected sizes were amplified from the genomic DNA of E. floccosum (571 bp), M. audouinii (598 bp), M. canis (571 bp [Fig. 4B]), M. cookei (569 bp), M. fulvum (605 bp), M. gypseum (581 bp), and M. nanum (588 bp). T. mentagrophytes and T. tonsurans shared a common PCR primer pair that amplified a 571-bp fragment; similarly, 581-bp fragments were amplified from T. rubrum, T. verrucosum, and T. violaceum by a common PCR primer. All of the primer pairs did not amplify the human DNA or any of the reference organisms.

Molecular assessment of the viability of dermatophytes in skin scales.

Table 1 shows the results of the evaluation of dermatophytic viability in skin scales based on the detection of dermatophyte ACT mRNA by RT-3′RACE-nested PCR. A 171-bp ACT cDNA amplicon was produced by RT-3′RACE-nested PCR of total RNA extracted from a portion of each of the 20 samples, which were incubated for 48 h in YCB broth; five were negative for dermatophytic mRNA. RT-3′RACE-nested PCR of total RNA, which was extracted directly from sample portions without prior culturing in YCB, produced the 171-bp amplicon from only 7 samples; 18 samples were negative. The internal-control PCR produced a 138-bp fungus-specific DNA amplicon from the genomic DNA extract of the 20 dermatophyte samples that were ACT mRNA positive and the 5 negative samples. PCR of genomic DNA extract using T. rubrum- and T. mentagrophytes-specific primers produced 581- and 571-bp fragments from 18 and 2 samples, respectively. Corresponding cultures of the samples in Sabouraud agar yielded isolates of T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes. Yeastlike isolates were recovered from three samples while two showed no fungal growth.

TABLE 1.

ACT mRNA-based determination of viability of dermatophytes in skin scrapings from 25 cases of hyperkeratotic human sole

| Test result | No. of samples by test method

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture (identity) | Intron-targeted PCR (identity) | YCB-cultured samples by ACT mRNA-targeted RT-3′RACE-nested PCR | Noncultured samples by ACT mRNA-targeted RT-3′RACE-nested PCR | |

| Dermatophyte positive | 20 (T. rubrum, 18; T. mentagrophytes, 2) | 20 (T. rubrum, 18; T. mentagrophytes, 2) | 20 | 7 |

| Dermatophyte negative | 5 | 5 | 5 | 18 |

DISCUSSION

A DNA fragment, identified as an internal partial length of the gene encoding the actin protein, was amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA extracts of 12 species of dermatophytes and then sequenced. Since there was no prior report on the dermatophytic ACT sequence, the primary isolation primers were designed to anneal on the ACT sequence of A. capsulatus, a member of the monophyletic order Onygenales, from whose ancestor the family of dermatophytic fungi also evolved (13).

An important feature of the isolated fragment of dermatophyte ACT is the associated intron. Studies on the insertion sites of the intron in the ACTs of various eukaryotes indicate that the location site, codon 301 (−3), is found in the actin genes of fungal species but not in any other eukaryotic species (21). The dermatophytic ACT introns lacked an internal open reading frame encoding a functional endonuclease, thus indicating the immobility of the intron (4, 12, 15).

An analysis of the dermatophyte ACT intron showed the presence of a short internal consensus sequence, the CTAAC box, which is an essential splicing signal sequence (11). The efficient in vitro excision of the intron by RNA splicing facilitated the differentiation of the RT-PCR product from amplicons that might have originated from the genomic ACT. The presence of the ACT-associated intron in all of the isolates of dermatophytes indicates the wide if not universal distribution of the intron among the dermatophytes. The differences in nucleotide sequences of the ACT-associated introns of different species of dermatophytes was exploited in the design of species-specific PCR primers. The Microsporum species were specifically distinguished by PCR, as was E. floccosum. T. rubrum was differentiated from T. mentagrophytes, although the former cross-reacted with T. verrucosum and T. violaceum and the latter with T. tonsurans. The complete sequence identities of the ACT-associated introns among these two Trichophyton groups probably reflect their close phylogenetic relationships (5, 7, 14). Thus, the ACT is less suited than the ITS regions of the DNA as a PCR target for the specific identification of dermatophytes; the latter have been used to differentiate several species of the three dermatophyte genera (6, 7, 8, 14, 20). The highly conserved ACT fragment was, however, suitable for the design of dermatophyte group-specific primer systems.

Actin-mediated cellular functions such as cytokinesis, exo- or endocytosis, chromosome segregation, organelle transportation, and cell shape change are all useful indicators of cell growth (17, 18). Thus, an actively transcribing actin gene indicates a need for the actin protein by a growing cell. On this basis, we indexed the specific detection of dermatophyte ACT mRNA in the total RNA extract of skin scales, by RT-3′RACE-nested PCR, to the presence of viable dermatophyte cells in tissue. RT-3′RACE-nested PCR is highly sensitive, and an earlier study showed that amplicons from 50 fg of total RNA of fungi were visualized following electrophoresis on an agarose gel (16).

In this study, the detection of dermatophyte ACT mRNA in total RNA extracts of scale samples corresponded with cultural isolation from samples. However, the positive rate of ACT mRNA was higher in the cultured samples of skin scales than the noncultured ones since the 48-h incubation in YCB served to increase the amount of fungal ACT mRNA available for transcription, amplification, and subsequent detection in an agarose gel. In our experience, the positive rate of detection of dermatophyte ACT mRNA in noncultured skin scales depended on the intensity of infection and amount of sample available for total RNA extraction (usually ≥20 mg of scale). In such cases, positive results were achieved within 8 h. Further improvement in the extraction efficiency of total RNA is needed to enhance the detection of dermatophyte ACT mRNA in total RNA directly extracted from minimal amounts of noncultured scales, thus eliminating the need to culture samples.

The advantages of ACT mRNA-based assessment of dermatophytic viability in dermatophyte-infected skin samples over the conventional culture methods include the achievement of results within a relatively shorter period, thus preventing unnecessary prolongation of therapy, and the elimination of problems of culture contamination and failure. The major disadvantages include dependency of results on efficiency of nucleic acid extraction and the possible degradation of mRNA leading to a false-negative result. The detection of dermatophyte ACT mRNA in skin scales as a means of evaluating fungal viability may have potential as a tool for the rapid assessment of the therapeutic efficacy of antimycotic agents.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barkan A. Tissue-dependent plastid mRNA splicing in maize: transcripts from four plastid genes are predominantly unspliced in leaf meristems and roots. Plant Cell. 1989;1:437–445. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock M, Nickel P, Maiwald M, Kappe R, Naher H. Diagnosis of dermatomycoses with polymerase chain reaction. Hautartzt. 1997;48:175–180. doi: 10.1007/s001050050566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borson N D. A lock-docking oligo (dT) primer for 5′ and 3′ RACE PCR. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;2:144–148. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dujon B. Group 1 introns as mobile genetic elements: facts and mechanistic speculations — a review. Gene. 1989;82:91–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gräser Y, El Fari M, Vilgalys R, Kuijpers A F A, de Hoog G S, Presber W, Tietz H-J. Phylogeny and taxonomy of the family Arthrodermataceae (dermatophytes) using sequence analysis of the ribosomal ITS region. Med Mycol. 1999;37:105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gräser Y, El Fari M, Presber W, Sterry W, Tietz H-J. Identification of common dermatophytes using polymerase chain reactions. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:576–582. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harmsen D, Schwinn A, Brocker E-B, Frosch M. Molecular differentiation of dermatophytic fungi. Mycoses. 1998;42:67–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.1999.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson C J, Barton R C, Evans E G V. Species identification and strain differentiation of dermatophyte fungi by analysis of ribosomal-DNA intergenic spacer regions. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:931–936. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.931-936.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kano R, Nakamura Y, Watari T, Watanabe S, Takahashi H, Tsujimoto H, Hasegawa A. Phylogenetic analysis of 8 dermatophyte species using chitin synthase 1 gene sequences. Mycoses. 1997;40:411–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1997.tb00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kappe R, Okeke C N, Fauser C, Maiwald M, Sonntag H-G. Molecular probes for the detection of pathogenic fungi in the presence of human tissue. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:811–820. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-9-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langford C J, Klinz F-J, Donath C, Gallwitz D. Point mutations identify the conserved intron-contained TACTAAC box as an essential splicing signal sequence in yeast. Cell. 1984;36:645–653. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90344-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasker B A, Smith G W, Kobayashi G S, Whitney A N, Mayer L W. Characterization of a single group 1 intron in the 18S rRNA gene of the pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Med Mycol. 1998;36:205–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leclerc M C, Philippe H, Guého E. Phylogeny of dermatophytes and dimorphic fungi based on large subunit ribosomal RNA sequence comparisons. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32:331–341. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makimura K, Tamura Y, Mochizuki T, Hasegawa A, Tajiri Y, Hanazawa R, Uchida K, Saito H, Yamaguchi H. Phylogenetic classification and species identification of dermatophyte strains based on DNA sequences of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 1 regions. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:920–924. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.920-924.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okeke C N, Kappe R, Zakikhani S, Nolte O, Sonntag H-G. Ribosomal genes of Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii and var. farciminosum. Mycoses. 1998;41:355–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1998.tb00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okeke C N, Tsuboi R, Kawai M, Yamazaki M, Reangchainam S, Ogawa H. Reverse transcription-3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends-nested PCR of ACT1 and SAP2 as a means of detecting viable Candida albicans in an in vitro cutaneous candidiasis model. J Investig Dermatol. 2000;114:95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollard T, Selden C, Maupin P. Interaction of actin filaments with microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:335–375. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.33s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reisler E. Actin molecular structures and functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(05)80006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiss E, Tanaka K, Bruker G, Chazalet V, Coleman D, Debeaupuis J P, Hanazawa R, Latge J P, Lortholary J, Makimura K, Morrison C J, Murayama S Y, Naoe S, Paris S, Sarfati J, Shibuya K, Sullivan D, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. Molecular diagnosis and epidemiology of fungal infections. Med Mycol. 1998;36:249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turenne C Y, Sanche S E, Hoban D J, Karlowsky J A, Kabani A M. Rapid identification of fungi by using the ITS2 genetic region and an automated fluorescent capillary electrophoresis system. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1846–1851. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1846-1851.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber K, Kabsch W. Intron positions in actin genes seem unrelated to the secondary structure of the protein. EMBO J. 1994;13:1280–1286. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]