Abstract

Analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on supply management, this article identifies “synchronicity management” as a novel supply risk management strategy. Synchronicity management synchronizes the supply chain with customer demand. In this way, overreactions to crises can be prevented. First, we introduce the supply risk management model from Hoffmann et al. (2013) and use this model to analyze our results from 26 interviews on supply management implications of the corona crisis with companies in a Central European region. Based on this, we derive suggestions for holistically improving future supply risk management processes and derive four propositions on how to manage crisis from a supply perspective. In addition, we explore implications for supply risk management from a strategic and operative point of view. In this context, we present a tool on how procurement can synchronize the supply chain with customer demand changes. Finally, future trends in supply chain risk and resilience management are being analyzed.

Keywords: COVID-19 crisis, operative and strategic implications, purchasing, supply risk management, synchronicity management, supply chain risk management model

I. Introduction: The Role Of Sales In Supply Manager's Reaction To COVID-19

In 2020, the world was hit by the largest ever supply chain interruption taking place on earth, induced by the spread of the COVID-19 virus (corona). With some companies, interestingly, the crisis had relatively limited impact in terms supply levels, i.e., they managed to provide their operations with a sufficient, but not excessive stock of supplies. The question is why this was so and what did these companies do better than their more affected peers, which either failed to provide goods or failed to keep efficiency high and caused financial damage by overstocking? How can a holistic risk management look like, which helps to create resilience with future crises?

Off course, one of the reasons for the reduced immediate supply impact may be particular due to the COVID-19 crisis. It started in China and hit Europe about six weeks later, only, thus being a crisis “in slow motion.” This time-lag, together with the fact that supply materials originating from China were already on the boat, gave firms some time to react. Shipments continued to arrive even after suppliers suffered production stops due to the shut-down. Nevertheless, many companies reacted to the crisis by increasing their stocks: Buying material available on the market. Others were asking suppliers still operating to produce extra quantities. Yet, companies might increase their stocks too much, which is a typical reaction at crisis time. This has also been observed in previous crises, presumably because demand changes are underestimated [Tsinopoulos, 2009].

Mitigating supply chain risks by systematically taking demand changes as departure point is in line with a novel approach discussed in supply risk management research: closely monitoring not the largest suppliers, but those vendors that have the biggest impact on profitability [Burghart, 2017]. In this article, we explore this approach further, suggesting to integrate systematic “synchronicity management” as a risk mitigation strategy into a supply risk management system.

Synchronicity management means to synchronize the supply chain and its risk mitigation strategy with customer demand changes. Systematically synchronizing supply and demand firms can keep their production running. Furthermore, they can ensure supply, manage cash flow, and ultimately achieve a better result than their overreacting competitors unilaterally trying to keep production running, but driving costs up.

In the following, this article is going to briefly introduce the supply risk management model from [Hoffmann et al., (2013)] and then use this scheme to analyze the findings from our research on firm's reactions to the COVID-19 crisis. We closely monitored and interviewed a sample of 26 firms in a Central European region, identifying a set of successfully crisis managing firms. Based on this, we derive four propositions on how to manage crises from a supply perspective, out of which the synchronicity approach may be the most important proposition. Finally, we can then briefly discuss enduring changes, which might be induced by the 2020 crisis.

II. Supply Risk Management: Distinguishing Between Environmental, Operational, Financial, And Strategic Risks

We define supply risk management as the activities that a buying firm undertakes to recognize, monitor, and mitigate supply risks. Supply risk being the “chance of an undesired event associated with the inbound supply of goods and/or services which have a detrimental effect on the purchasing firm and prevent it from meeting customers’ demands within anticipated cost and time” ([Hoffmann et al., 2013], p. 201). In this definition, we clearly distinguish a difference between the risk source (the undesired event) and the risk outcome (the detrimental effect). Supply risk outcomes are oftentimes caused by a combination or chain reaction of multiple risk sources [Bogataj et al., 2016].

Supply risk sources can be classified as environmental risk sources and behavioral risk sources [Hoffmann et al., 2013]; see Figure 1. Environmental risk sources are events in the environment of a supply chain relationship that can cause problems, such as terrorist attacks, labor strikes, or natural disasters. The current COVID-19 crisis classifies, first, as an environmental risk. Environmental risks affect all firms in the respective market. Behavioral risk sources are specific to a buyer–supplier relationship. They arise either at the supplier or within the relationship. They can be subdivided into 1) financial risk sources—the change on supplier default insolvency or bankruptcy; 2) operational risk sources—the inability of a supplier to live up to the buyer's requirements; and 3) strategic risk sources—the change of not being treated as a preferred customer, i.e., the unwillingness of a supplier to live up to the buyer's requirements, even though, in principle, it could.

Figure 1.

Supply risk model.

Williams et al. [2017] distinguished between one-time events and enduring crises. The current; crisis can be regarded as a one-time event. It was a low probability, unanticipated, harmful, and unpredictable event. They argue that research on crises should be integrated with resilience research, as those two concepts have a recursive relationship with each other [Williams et al., 2017]. Building resilience can help firms to better mitigate adversities or risks. It also works the other way around: risk management is a key enabler to achieve resilience, i.e., to cope with external shocks such as a pandemic [Pereira et al., 2014].

Resilience can be understood as a dynamic attribute of a firm that—as a process in time—enables to be observant for, responsive to, and overcome crises [Conz and Magnani, 2020]. In their article on resilience, Conz and Magnani [2020] characterized two risk mitigation strategies (i.e., resilience types): “absorptive” and “adaptive”:

-

1.

In an absorptive resilience path, firms aim at robustness and the preservation of organizational structures and processes. Relevant capabilities are redundancy, robustness, and agility.

-

2.

In an adaptive resilience path, the focus lies on using novel resources and changes in processes, to enable the shift to a new equilibrium. Related capabilities are resourcefulness, adaptability, and flexibility.

Based on the distinction between these two contrasting strategies and the reaction to the four facets of risk, it becomes possible to analyze supply managers’ reaction to the COVID-19 crisis, to which the following section is dedicated.

III. Methods: Screening Crisis Impact in an Industrial Region

Semistructured interviews were conducted as a qualitative survey instrument. A semistructured interview is described as a verbal interchange between persons [Longhurst, 2003]. The interviewer wants to receive information from the interviewed person and asks different questions from a list of a predetermined questionnaire. Semistructured interviews are designed in a conversational manner. They allow participants to explore topics they consider important [Longhurst, 2003]. The data derived from semistructured interviews are more rich than data received from strictly quantitative studies [Sankar and Jones, 2007]. Disadvantages may arise due to the bias of the persons, who are active in the interviewed organization or company [Boyce and Neale, 2006]. In fact, a further important bias may occur with the interviewees due to a time lag between occurrence of an event and reporting it. In the present case, however, this bias is avoided: interviews on the reaction to the COVID-19 crisis were taken during the event.

For our research we conducted 26 interviews in the EUREGIO-region, located at the Dutch–German border (20 firms in NL and 6 in D). The interviewed companies have a high share of suppliers located abroad and are embedded in an international network of suppliers. The majority of the interviews were conducted with companies which are affected by “remote sourcing.” Remote sourcing - or transcontinental sourcing - means that suppliers of a firm are situated in other continents. In context of these interviews, a large part of companies had important suppliers in China.

Due to the coronavirus shut down, the interviews were conducted by phone or recorded by MS TEAMS. Every interview lasted approximately one hour. After data collection, all data were analyzed and results were documented. In addition, software was used to document and analyze the interviews.

IV. The Covid-19 Crisis as an Asynchronous Global Calamity

A. Environmental Risk: Strategy Follows Customers

Most of the firms in our sample have a very global supply chain including suppliers in China. They were first affected by the shutdown of this country. One firm explained:

“When it went wrong in China we thought like, let's just focus on Italy because we also have suppliers there. But, after China, that was the place that was hit the heaviest by the coronavirus. And when Italy closed down, China was opening up again.”

In so far the COVID-19 crisis has a special character, being asynchronous and thus more easily manageable. Even more as firms with such remote supplier's generally operate with larger buffers than firms with local, just-in-time suppliers. Being like this, it might be important to distinguish if an environmental risk is becoming active only in the supplier's or the buyer's place, or in both. The asynchronous case causes less severe management implications.

In the interviews, we asked firms which options they choose (following resilience management theory): (1 either an absorptive strategy (trying to keep production running) or (2 an adaptive strategy (stopping and preparing for later ramp-up).

However, not always did firms have any strategic choice:

“It's your customer that dictates your strategy. […] And the only thing we can do is be as close as possible with our suppliers.”

Interestingly, it may not be wise to try to establish its own strategy, as one firm discovered by observation:

“So that demand evenly went down together with what suppliers could offer us.”

Four out of the observed firms commented on the demand side changes influencing their supply strategy. Two of them were systematically doing so, by analyzing the development of their runners, the best-selling products:

“And for the rest of what we have done, our good-selling products have been well-monitored like do we have to buy extra.”

Several other companies, on the contrary, did not monitor their sale's development and stockpiling their storage buffers by “buying what you can” (hoarding).

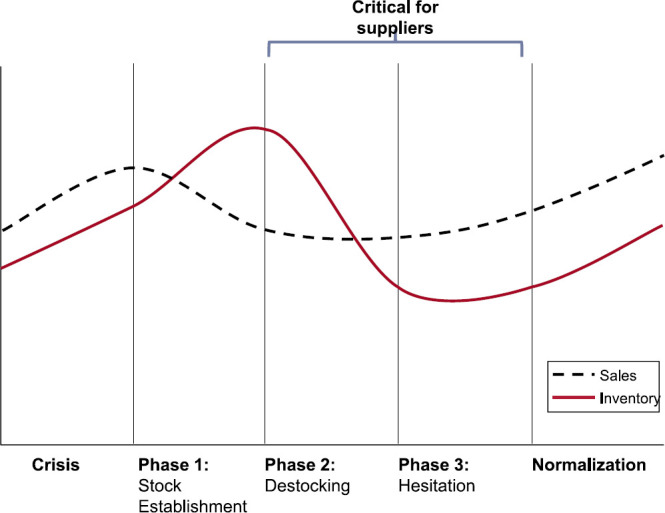

In previous crises, for instance, in the economic crisis of 08/09 following the collapse of the U.S. real-estate market, it has also been empirically observed that first, the inventory levels go up, as firms either do not recognize the change or may actively try to secure stocks [Tsinopoulos, 2009]. Then, in the second phase, destocking occurs, often in excess of necessity or driven by cash flow considerations. The third phase is characterized by hesitation, as firms still miss a clear signal of recovery, before, eventually, normalization takes place (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phases of crises.

Based on the multiphase logic of crises and the observations of first management approaches explicitly emphasizing the customer's reaction, we propose the following:

Management proposition 1: In crises, risk mitigation strategies should be synchronized with customer demand changes.

B. Operational Risks: Communicate, Communicate, and Communicate

The reaction facing the COVID-19 crisis, from an operative perspective, typically seemed to follow these steps:

-

1.

Hygienic measures, such as distribution of mask and assurance of safety distances between the works were implemented. This is obviously a step characteristic to a pandemic, which may not apply if other reasons lead to a crisis.

-

2.

Once the purchasers and supply chain managers became aware of the problems, intensive direct talks with suppliers started, to map the supply chain and subsequently ensure supplies.

“We were not prepared, so we did not have a strategy in place and we were not the only ones. So we tried to map that information as soon as possible and we did that via E-mail, telephone and telecalls. Then a strategy forms itself and in a week you have a lot of information about where you are and you have the ability to rescale and refocus.”

-

3.

In many cases, immediate reactions referred to the attempt to buy stock: “What we did was buy stock that already arrived in Europe so just like bulk because we saw what happened in China. So I said to suppliers: I would like to buy everything you have on stock now.”

-

4.

Fly in supplies (depending on the approach and the decision to continue production, i.e., following the “absorptive” strategy trying to keep production running).

Reports on crisis management typically come to the same conclusion, summarized by Pereira et al. as “intense collaboration between the buyer and a critical supplier to overcome any supply disruptive events” ([Pereira et al., 2020, p. 9]). They provide a series of details on operative activities, such as exchanging materials and reallocating them. In addition, modifying transport routes and means, even exchanging personnel to ensure preferential solutions.

Based on this communication intensive pattern, we conclude with the following proposition:

Management proposition 2: Ensure and apply an intensive communication structure with the key suppliers, based on a good relationship.

C. Financial Risks: Considering Cash

Only few of the interviewed supply managers in our sample expressed a particular attention to financial and cash issues, with some exceptions:

“The press conferences were quite thrilling for us […], if they're going to close everything. We're going to be busy monitoring the cash flow. This was also important in the beginning [of the crisis], it was a bit of a balance between, monitoring cash flow and security of delivery where we also noticed hamster behavior from our customers.”

What this firm was discussing in regular meetings refers to financial risks which start to built-up in phase 1 of the crisis (see Figure 2), when some firms suffer from cash outflow due to overstocking. Then, in phases 2 and 3, when demand breaks down, this can mount to a critical level. It results in financial problems, also with suppliers. Based on a financial supply risk management logic, we propose the following:

Management proposition 3: Throughout the diverse phases of a crisis, keep the cash flow and financial situation in view, including the finances of the supplier.

D. Strategic Risks: Being Partner of Choice

The strategic risk perspective is often neglected in risk management. In situation of crises, these risks, which during a normal business situation might have remained under the surface, emerge [Reichenbachs et al., 2017]. The challenge for buyers is to get the preference of their suppliers, if these have to make the choice whom of their customers get material in times of scarcity.

With the COVID-19 crisis, a special aspect became noticed:

“What I do notice is that hospitals have gained preferred treatment in these times of corona. […] companies do have the policy that they have to do something for the community so they first deliver to hospitals.”

A similar observation was reported from a firm active in the energy sector, which also counts as critical and societally desirable. “Community value” is an interesting, novel factor for explaining preferential resource allocation, so far not reported in the literature.

A challenge European firms have been noticing refers to the declining preferential treatment they get in China, due to the emergence of significant local demand.

“The biggest advantage that existed 10 years ago when the whole drive started to go to China, costs, is slowly disappearing. At that time, there was no local demand in China. The local demand has changed in China.”

To overcome the challenges of not being a strategical customer to the supplier, one of the interviewed firms explained that they had contractually secured storage beforehand. This feature proved to be helpful in the moment of shortages. Not because the supplier would necessarily have all the material on stock. However, the supplier would then allocate the remaining production capacity to this customer. Based on this, we propose:

Management proposition 4: Create resilience through actively managing to achieve preferred customer status with critical suppliers.

Figure 3 summarizes the suggested management approach, which reflects our holistic risk management model, addressing all four generic types of risks, respectively, risk facets.

Figure 3.

Risk mitigation strategy.

As point of departure and anchor point our findings suggest the following: firms may take the development of the customer's demand as starting point to determine the own risk mitigation strategy, once a crisis has become viral. Such synchronicity management requires a dedicated management approach, a blueprint of which we are going to propose in the following section.

The execution of this strategy stands under the condition of cash flow considerations. Both for the own firm, as, in the second and third phase of the crisis, with suppliers, who may go out of business due to a lack of financial means. In parallel and operationally, the execution of the risk mitigation mechanisms involves a permanent and intensive communication with the suppliers. For the latter to be successful, the buyer needs to be of sufficient importance for the supplier to execute the necessary adjustments. These typically involve scheduling and logistic adjustments as well as stock and production capacity reallocation [Pereira et al., 2020]. In order to be well positioned for a crisis and then get the privileged treatment by its suppliers, firms may in advance have to set the scene: they create resilience by systematically becoming a preferred customer of their key suppliers ([Pulles et al., 2019]; [Reichenbachs et al., 2017]; [Schiele, 2012]). Buying firms need to understand how their suppliers evaluate them, subsequently measuring and improving their suppliers’ satisfaction to the point that they become better customers than the other customers of the supplier.

V. Implications: Featuring Synchronicity Management

A. Operative Implication: A Tool on How to Synchronize the Supply Chain With Customer Demand Changes

The analysis of the reaction on the COVID-19 crisis by the firms in our region has spotted the importance of synchronizing the supply risk mitigation strategy of a firm with the development of the demand by its customers. Supply departments which are disconnected from their firm's sales/marketing may in the end ensure supply at high cost and cash flow loss. At the same time, for the final products the demand has broken down as consequence of the same crisis. The question must be discussed jointly how sales assess their customer's reaction to the crisis.

At the same time, it became clear that keeping the supply chain robust requires a very intensive communication with suppliers, as capacity constraints at suppliers may occur. This problem is mirroring one of the core challenges professional supply risk management faces. Research has shown that the process of cross-functional exchange on suppliers is a highly efficient way to detect and handle supply risks. However, it comes at the expense of strong resource commitment [Hoffmann et al., 2013]. But resource constraints limit the ability of organizations in paying equal attention to all partners. The question arises as to how identify these critical suppliers, i.e., those which (need to) get individual attention by supply risk management? Traditionally, the large A and B supplier accounting for 80% of the purchasing volume is taken as point of departure for applying individual risk assessments.

Recently, the idea has been proposed for supply risk management not to take the largest suppliers as starting point for risk management, but those with the largest impact on sales and profit [Burghart, 2017]. We have tested this model in the case of a risk management system for a chemical company. The result is displayed in Figure 4. If the traditional assumption of large purchasing volume equaling large sales impact would have been true, most cases would have plotted around 45° line. But they did not. Clearly, that company had a couple of small suppliers, whose products, however, were central to many final products. Hence they were much more critical than, for instance, the large volume suppliers in the lower right end of the graph. Suppliers located in the left upper corner, then, are those critical ones to be addressed first.

Figure 4.

Sales risk chart.

Summarizing, for the risk mitigation we propose the following steps:

-

1.

Identifying a company's most profitable products (and in case of nonavailability of reliable data those with the largest sales).

-

2.

Identify the most critical suppliers involved in these products and implement regular risk assessment (those above the highest dotted line in Figure 4; please note that they do not strictly correlate with spend volume).

-

3.

In the case of the occurrence of an environmental risk, such as COVID-19: Sales systematically assesses the impact of the event by contacting the critical customers. Based on this assessment (which is superior to a generic intuitive evaluation of sales changes) purchasing and supply, know which suppliers are more critical and need to be contacted for operational reasons.

-

4.

First, identify financially unstable suppliers among the critical group (indicators such as: low equity ratio, payment behavior, ownership change).

-

5.

Identify preferred customer status with each of these suppliers (indicators such as: supplier response in the past, change own turnover, market share supplier, hierarchical position of contact).

-

6.

Dedicate resources to ramp-up/maintain the most profitable chain with supplier where the company enjoys high status and which contains few financially unstable suppliers.

-

7.

Analyze the next product—supply chain and identify possible synergies among them, and so on.

In the end of this exercise, the most efficient resource input/value output ratio can be realized.

B. Strategic Implication: The Crisis as Trend Accelerator, But Not Disruptor

In this research, we analyzed the reaction to the COVID-19 crisis by a series of internationally active industrial firms in a European border region, applying a risk management lens. The particular importance of synchronizing supply and demand in a crisis situation, the operative importance of cash flow management and intensive interaction with the suppliers and the strategic need to build up resilience potential though being a preferred customer of key suppliers emerged as core topics of a crises-proof supply management. Remains open the question on the expectations toward a sustainable impact of the crisis.

Contrary to our expectations, most respondents expressed the view that the COVID-19 crisis does not seem to lead to fundamental changes in their firm´s strategy. For instance, the basic empirics of stock holding or request for freshness of goods does not change, neither the importance of supplier management and the aspects of financial risks regarding Global sourcing.

This is also illustrated by the following statement:

“People say that you make the stocks or increase them, maybe you can do it once in an uncertain time. But at some point someone will come along and say, people say, do we really always have to have so much money in stock? And then it will be abolished again.”

The crisis may mainly strengthen already ongoing trends, such as backshoring from China due to increasing costs and the missing preferred costumer status because of domestic demand and competition with local firms. This trend to localize can be seen in many industries, also due to the last global economic crisis [Kinkel, 2012]. This also concerns the special form of Global Sourcing: Remote sourcing, with a high share of important suppliers located on other continents, in this case, mainly, in China. So the crisis may accelerate existing trends such as the localization of certain industries. However, the hypothesis put forward would be that environmental risk induced crises do not seem to represent a disruptor which generates structural changes. An explanation could be that an environmental risk materializing does not lead to fundamental change, because each and every company is affected. The relative risk compared to others remains the same.

A trend likely to accelerate even more is the emphasis on risk management. There are even theories, such as the Austrian industry cycle theory, which argue that one crisis bears the potential to generate the next crisis: governments may overspend to fight a crisis, therewith provoking a faster than normal recovery, which is not sustainable because it might have been propelled by anticipating demand (i.e., consumers buy goods they would, without government incentive, have only bought later; producers react by investing into new production capacity, which they would also not have done without incentive). This demand is then missing in the subsequent period (because it had already been fulfilled). As a consequence, firms have then build up a high level of overcapacity; they do not find buyers for their output. This means that the economy falls into the next recession and the cycle starts all over again.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all participants of this study and the support of Nevi Oost, who helped to establish the panel.

Contributor Information

Holger Schiele, Email: h.schiele@utwente.nl.

Petra Hoffmann, Email: p.hoffmann@utwente.nl.

Thomas Köerber, Email: t.m.koerber@utwente.nl.

References

- Bogataj, D., Aver, B., Bogataj, M. (2016). Supply chain risk at simultaneous robust perturbations. International Journal of Production Economics 181, 68–78.

- Boyce, C., Neale, P. (2006). Conducting -Depth Interviews: A Guide for Designing Conducting -Depth Interviews for Evaluation. Input. Watertown: Pathfinder International. [Google Scholar]

- Burghart, S. (2017). Integrierte Risiko-Analyse. Erfolgsrelevante Risiken Identifizieren. Beschaffung Aktuell, 63(5),32.

- Conz, E., Magnani, G. (2020). A dynamic perspective on the resilience of firms: a systematic literature review and a framework for future research. European Management Journal , 38(3), 400–412.

- Hoffmann, P., Schiele, H., Krabbendam, K. (2013). Uncertainty, supply risk management and their impact on performance. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management , 19(3), 199–211.

- Kinkel, S. (2012). Trends in production relocation and backshoring activities: changing patterns in the course of the global economic crisis. International Journal of Operations and Production Management , 32(6), 696–720.

- Longhurst, R. (2010). Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. In Key Methods in Geography, N. Clifford, S. French, and G. Valenine, Eds. Los Angeles, CA, USA: Sage, 103–115.

- Pereira, C. R., Christopher, M., Silva, A. (2014). Achieving supply chain resilience: the role of procurement. Supply Chain Management, 19, 626–642. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, C. R., Silva, A., Tate, W. L., Christopher, M. (2020). Purchasing and supply management (PSM) contribution to supply-side resilience. International Journal of Production Economics, 228, 107740. [Google Scholar]

- Pulles, N. J., Ellegaard, C., Schiele, H., Kragh, H. (2019). Mobilising supplier resources by being an attractive customer: relevance, status and future research directions. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 25(3). [Google Scholar]

- Reichenbachs, M., Schiele, H., Hoffmann, P. (2017). Strategic supply risk: exploring the risks deriving from a buying firm being of low importance for its suppliers. International Journal of Risk Assessment and Management , 20(4), 350–373.

- Sankar, P., Jones, N. L. (2007). Semi-structured interviews in bioethics research. In Empirical Methods for Bioethics: A Primer. Bingley, U.K.: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Schiele, H. (2012). Accessing supplier innovation by being their preferred customer. Research-technology Management , 55(1), 44–50.

- Tsinopoulos, C. J., Mark. (2009). Boom and Bust—The Impact of Economic Recessions on Operations Strategy: Some Preliminary Results. Paper presented at 16th EurOMA Conf., Goteborg, Sweden.

- Williams, T. A., Gruber, D. A., Sutcliffe, K. M., Shepherd, D. A., Zhao, E. Y. (2017). Organizational response to adversity: fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 733–769. [Google Scholar]