Abstract

Objective:

We use the Framework of Historical Oppression, Resilience, and Transcendence (FHORT) to investigate the framework’s core concept of family resilience and related protective and promotive factors that contribute to greater resilience, namely communication.

Background:

Scant research has examined communication in Indigenous families; yet general research suggests that family communication is a prominent aspect of family resilience.

Methods:

In this exploratory sequential mixed-methods study with data from 563 Indigenous participants (n = 436 qualitative and n = 127 quantitative survey), thematic reconstructive analysis was used to qualitatively understand participants’ experiences of family communication and quantitatively examine protective factors for family resilience.

Results:

The following themes related to family communication as a component of family resilience emerged from qualitative analysis: “It’s in the Family Circle”: Discussing Problems as a Family with the subtheme: Honesty between Partners; (b) “Never Bring Adult Business into Kids’ Lives”: Keeping Adult Conversations Private; and (c) “Trust Us Enough to Come to Us”: Open Communication between Parents and Children. Regression analysis indicated that higher community and social support, relationship quality, and life satisfaction were associated with greater family resilience.

Conclusions:

Positive communication practices are a strong component of resilience, healthy Indigenous families. Promotive factors at the community (social and community support), relational (relationship quality), and individual (life satisfaction) levels positively contribute to Indigenous family resilience.

Implications:

Clinical programs providing practical tools to foster healthy communication – both about difficult topics as well as positive topics – are promising avenues to foster resilience.

Keywords: family communication, family resilience, Native American, social support

INTRODUCTION

Scant research has examined communication in Indigenous families; yet general research suggests that family communication is a prominent aspect of family resilience (Black & Lobo, 2008). Family resilience enables families’ successful coping under duress; a recent review of family resilience factors identified family communication (i.e., clarity, open emotional expression, and collaborative problem solving) as one essential tool promoting family resilience (Black & Lobo, 2008; Walsh, 2016). Family resilience promotes Indigenous health equity (Burnette, 2018; Burnette & Hefflinger, 2016; Burnette, Renner, & Figley, 2019; Burnette, Roh, et al., 2019; McKinley, Lesesne, et al., 2020).

Despite heterogeneity and resilience among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people (hereafter referred to as “Indigenous” when combined), colonial historical oppression has disrupted family structures and impaired health equity among Indigenous peoples across social, physical, and mental health dimensions (Ka’apu & Burnette, 2019; McKinley, Spencer, et al., 2020; Walters et al., 2011). Epidemiological data indicate that these populations tend to suffer profoundly high rates of health disparities in comparison with other populations (McKinley, Spencer, et al., 2020). Several reviews and empirical research indicate that in addition to chronic health, cancer, and physical health disparities (McKinley, Ka’apu, et al., 2020), depression, suicide, alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use, and post-traumatic stress disorder tend to be quite elevated for Indigenous peoples of the United States (AI/ANs and Native Hawaiians) (Ka’apu & Burnette, 2019). Yet, despite a U.S. Federal Trust Responsibility to provide for their well-being, Indigenous families continue to face significant disparities and are by and large underrepresented in mainstream research, which perpetuates an invisibility and contemporary form of oppression (McKinley, Miller Scarnato, & Sanders, 2020).

Family resilience, or the capacity of families to adapt to adversity threatening its functioning and viability, is understood to profoundly affect the well-being of individuals, communities, and whole societies (Masten, 2018). Indeed, research using the focal Framework of Historical Oppression, Resilience, and Transcendence (FHORT) (Burnette & Figley, 2017) has found that family resilience was protective against important Indigenous health disparities, including anxiety and depression (Burnette, Renner, & Figley, 2019), alcohol use (McKinley & Miller Scarnato, 2020), intimate partner violence (IPV) (Burnette, 2018), cancer (Roh et al., 2020), disaster recovery (McKinley, Miller Scarnato, et al., 2019), and overall wellness (McKinley, Spencer, et al., 2020). To contextualize these adverse experiences, the FHORT is a critical and postcolonial framework that introduces historical oppression as a societal-level risk factor, defined as the perpetual, chronic, and massive forms of historic and contemporary oppression, that were first imposed through colonization and have been perpetuated through internalization and continued systemic oppression (Burnette & Figley, 2017). A contribution of the FHORT is situating problems within their sociostructural and historic causes of historical oppression. Historic forms of oppression can include assimilative boarding schools, forced relocation, loss of land and lives, whereas contemporary forms of historical oppression can include discrimination, health inequities, and invisibility, among others.

The FHORT is a culturally congruent framework recommended for work with Indigenous peoples as it not only focuses on challenges or problems, but also includes a focus on resilience and health equity (Burnette & Figley, 2017). Recognizing the context of historical oppression in which Indigenous families are situated, the FHORT conceptualizes resilience by examining the balance of interacting risk, promotive, and protective factors across ecological levels. Through a relational framework that is congruent with Indigenous worldviews, the FHORT illuminates the interconnections of risk, protective, and promotive factors across individual, couple, familial, cultural, community, and societal levels (Burnette & Figley, 2017). Resilience is fluid, multi-determined, and evolving and interactive with the context (Masten & Monn, 2015; Waller 2001).

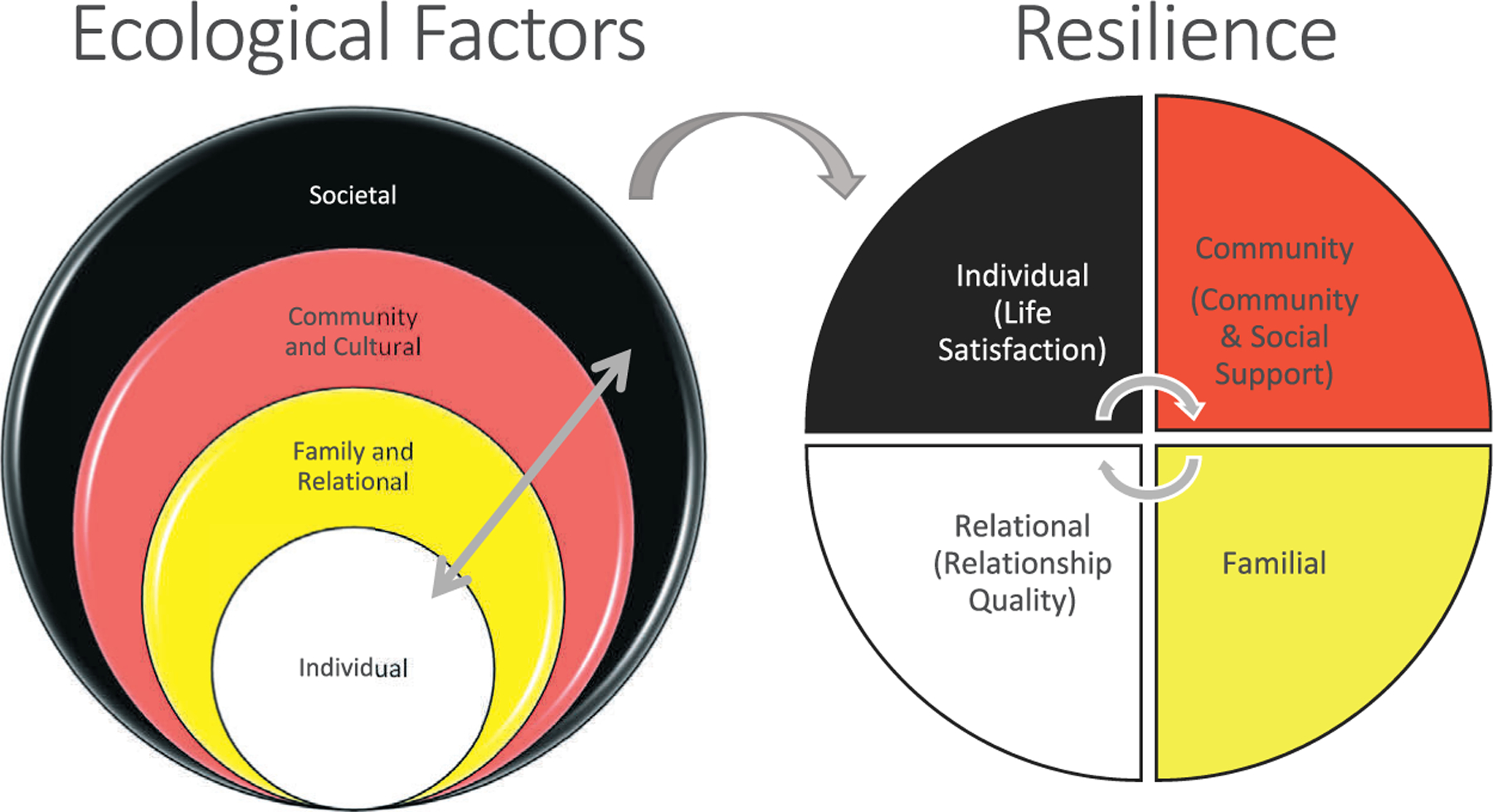

The FHORT posits that the interaction and harmony of factors across ecological levels explain and predict Indigenous resilience, despite experiencing historical oppression and associated adversity. Figure 1 displays the FHORT model with focal variables across these levels. For our purposes, risk factors exacerbate problems, protective factors buffer against negative outcomes or promote resilience, and promotive factors are strengths and resources that are beneficial whether adversity is present or not (Masten, 2018). For this article, we examine community, familial, relational, and individual protective and promotive factors. The FHORT is useful to understand and frame these ecological factors to understand and predict family resilience (Burnette & Figley, 2017). Within the FHORT, despite chronically experiencing historical oppression, the forms of which have been covered elsewhere (Burnette, 2016), some can experience transcendence and attain a deeper or higher level of life satisfaction and meaning, in part because of becoming liberated and breaking through oppression and adversity (Burnette & Figley, 2017).

FIGURE 1. Outcomes Related the Resilience Perspective of the FHORT.

The FHORT investigates the interaction and contribution of ecological risk and protective factors across societal, cultural and community, family and relational, and individual levels to predict outcomes related to wellness and resilience. We investigate community (communal and social support), relational (relationship quality) as well as individual (life satisfaction) dimensions of resilience. As such, we investigate key concepts of the FHORT (namely, aspects of ecological resilience). Adapted figure reprinted with permission from Burnette and Figley (2017)

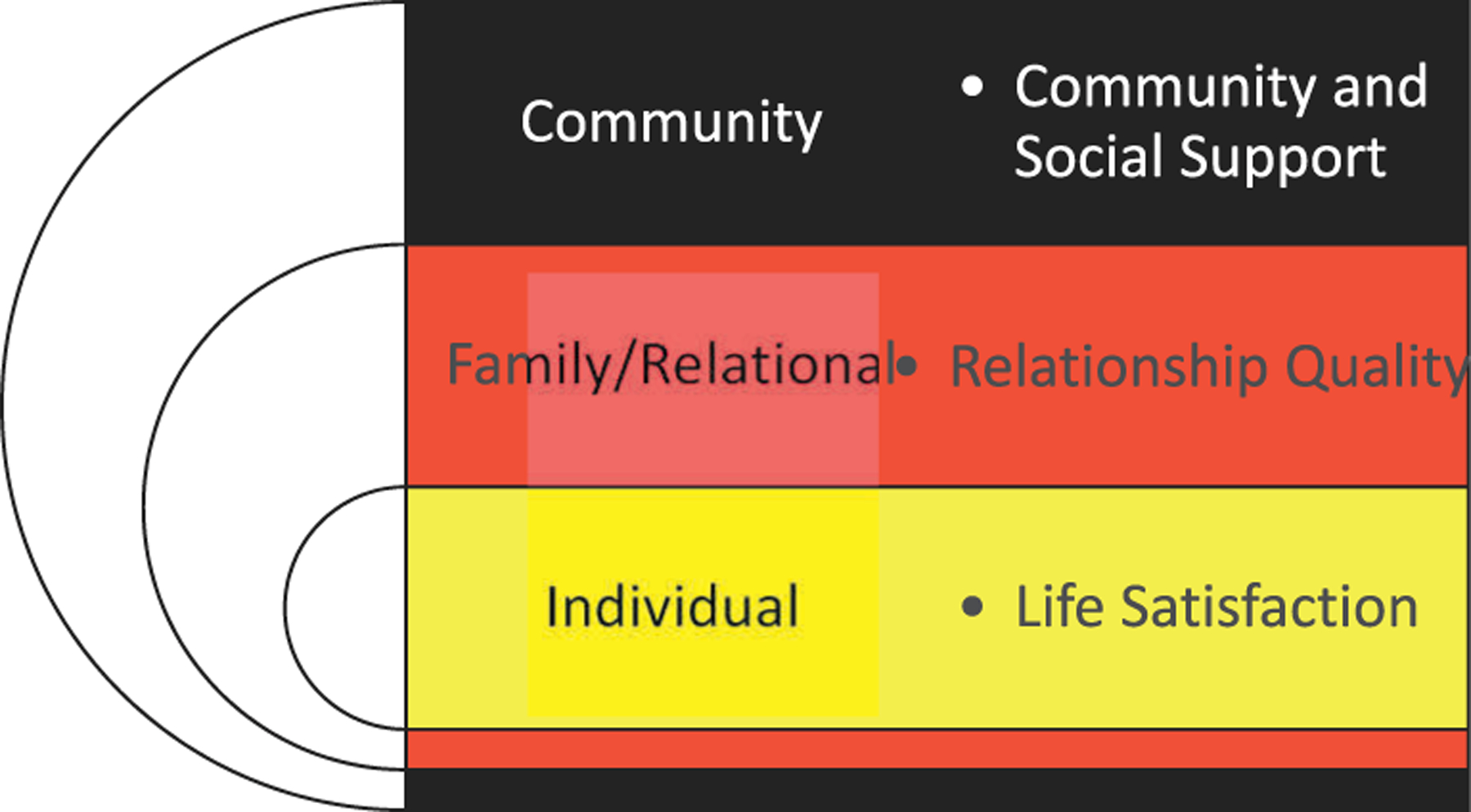

The purpose of this mixed-methods study is to examine key components of family resilience amongst Indigenous families from two tribes in the southeastern United States. Because most research draws attention to the deficits of minority populations (Stiffman et al., 2007), we focus on protective and promotive factors to explore Indigenous families’ resilience (Burnette, 2018; Burnette et al., 2020). We first qualitatively investigate communication, a component of family resilience (Burnette et al., 2020), amongst participants from two tribes. We then quantitatively examine ecological factors that may contribute to family resilience within the same two tribes; namely, community and social support, relationship quality, and life satisfaction (See Figure 2). As such, we use the FHORT to investigate factors across ecological levels and include key measures of the framework, namely the Family Resilience Inventory (FRI [Appendix A]) and life satisfaction, which is a measure of transcendence (Burnette et al., 2020; Burnette, Roh, et al., 2019). The FRI is a culturally congruent measure of family resilience, developed with and validated among Indigenous peoples (Burnette et al., 2020).

FIGURE 2. Ecological Promotive Factors Related to Family Communication and Resilience From the Perspective of the Framework of Historical Oppression, Resilience, and Transcendence.

We investigate the hypothesis that higher community and social support, relationship quality, and life satisfaction will be associated with higher family resilience. According to the FHORT, ecological risk and protective factors occur across ecological levels to give rise to differing levels of resilience. For this article, the focus is community, and relational, and individual levels. We investigate community (community and social support), family and relational (family resilience, social and community support, and relationship quality), and individual (life satisfaction) aspects of wellness. We investigate core components of the FHORT, such as resilience (e.g., family resilience) and transcendence (e.g., we use life satisfaction as a measure of quality of life and transcendence) in a holistic way

THE FHORT, FAMILY RESILIENCE, AND FAMILY COMMUNICATION

Families have been found to be the bedrock of resilience and support for youth, adults, and communities, and often buffer against disparities in health and social conditions that ethnic minorities tend to experience Burnette, 2018; Burnette, Renner, & Figley, 2019; Burnette, Roh, et al., 2019; McKinley, Roh, et al., 2020). Yet most resilience research focuses on individual, not family, resilience (Hawley, 2013). Family resilience is defined as “the capacity of the family system to withstand and rebound from adversity, strengthened and more resourceful” (p. 617), with a focus on positive adaptation and positive growth (Walsh, 2016). Multiple scholars have made influential contributions to the field of family resilience (Ungar, 2016; Walsh, 2016), though examination of Indigenous family resilience is limited. The FRI (used in this study and described in detail elsewhere) (Burnette et al., 2020) was one of the first comprehensive attempts to conceptualize and measure family resilience processes within Indigenous families specifically. Developed with Indigenous peoples to reflect their culturally- and contextually-specific experiences of resilience at the family level, the FRI explores several aspects of family communication (affective communication, laughter, protecting children from arguing, working through problems) as a component of family resilience (Burnette et al., 2020).

Openly communicating about problems and stress is a way to cultivate family resilience (Lucas & Buzzanell, 2012). Research demonstrates that families that engaged in difficult conversations about trauma and hardship experienced positive outcomes (Keating et al., 2013), whereas poor family communication was associated with adolescents’ increased risk for trauma symptoms (Acuña & Kataoka, 2017). Parent–child communication in particular has been found to promote individual and family resilience (Theiss, 2018). Such communication enables parents to model how to manage difficult emotions, adversity, and stress, which can promote family resilience (Theiss, 2018). The limited scholarship available on Indigenous families indicates that healthy parent–child communication helped prevent adverse outcomes for children (Beebe et al., 2008; Hennessy et al., 1999; Oman et al., 2006; Ramirez et al., 2002; Urbaeva et al., 2017).

Healthy family communication also may be related to relationship quality, conceptualized as how often people feel loved, supported, respected, and understood in their current relationships. From an Indigenous perspective, the FHORT utilizes a relational worldview to conceptualize resilience, making communication and family relationships important areas of inquiry in relation to family resilience (Burnette & Figley, 2017). Quality relationships among family members are related to family resilience and well-being (Black & Lobo, 2008; Grevenstein et al., 2019). Research found that better family relationships were associated with greater life satisfaction, an indicator of transcendence, according to the FHORT), decreased psychological distress, and higher resilience, sense of coherence, self-compassion, optimism, self-esteem, and efficacy, all of which contribute to family resilience (Grevenstein et al., 2019). Resilience is thought to foster greater life satisfaction indirectly through a reduction in negative emotions, such as depression, anxiety, and stress (Beutel et al., 2010; Samani et al., 2007). Research suggests that family resilience is also bolstered by community and social support (Black & Lobo, 2008). A review of the family resilience literature found that resilient families rely on social support from their community networks (Black & Lobo, 2008). For families living in contexts of poverty and social problems, like many Indigenous families, external support systems are especially influential in promoting positive outcomes (Black & Lobo, 2008). According to the FHORT, these protective factors– communication, relationship quality, life satisfaction, and community and social support – play important roles in family resilience processes within Indigenous communities (Burnette & Figley, 2017).

The purpose of this mixed methodology was to use the FHORT to qualitatively examine participants’ experiences of family communication as a component of family resilience. We examine how the protective factors of community and social support, relationship quality, and life satisfaction relate to family resilience (See Figure 1). The overarching research question for the qualitative component is: What role does family communication play in family resilience amongst Indigenous families? The quantitative inquiry examines the relationships among the protective factors of community and social support, relationship quality, life satisfaction as they relate to family resilience. Examining these factors increases understanding of how to bolster family resilience by increasing available supports across ecological levels (community, family/relational, and individual). Our predicted hypotheses are that higher community and social support, relationship quality, and life satisfaction will be associated with higher family resilience.

METHODS

Research design and setting

Research was conducted with two tribes in the Southeastern United States, which we refer to by the pseudonyms “Inland Tribe” and “Coastal Tribe” to protect community identity. The names and identifying information related to these tribes are kept confidential in accordance with ethical research guidelines (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). Both tribes are located near the Gulf Coast, with the Inland Tribe further inland and the Coastal Tribe more proximal to the coast. The Inland Tribe has received federal recognition, and provides and operates its own schools, social services, criminal justice system, and healthcare facilities. The Coastal Tribe has been denied federal recognition, but is recognized at the state-level. The Coastal Tribe provides some employment and education services for members.

The research employed an exploratory, sequential mixed-methods design, triangulating several forms of data (qualitative, and quantitative). Data were collected as part of a broader critical ethnographic study exploring the lived experiences and family resilience processes of Indigenous peoples in the focal tribes (McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). Critical ethnographies triangulate data sources to enhance rigor, and use critical theory to link analysis to systems of power (Carspecken, 1996). The research design and all research activities were guided by the “Toolkit for Ethical and Culturally Sensitive Research with Indigenous Communities” to maintain cultural sensitivity (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019).

Qualitative data collection with a total of 436 participants preceded quantitative data collection with 127 participants. Qualitative data included focus groups, family interviews, and individual interviews with participants across the lifespan (elders, adults, youth) and behavioral health professionals working within the focal tribes. Individual interviews employed a life history approach focused on the experiences of individual participants, family interviews engaged multiple individuals residing within the same household to understand family life and dynamics, and focus groups brought together working professionals and people of various age groups to share their perspectives. The latter enabled peer-groups to speak from a place of shared meaning through their respective age or professional roles. Semi-structured interview guides for each data collection type followed the same topics, with slight variations to maintain appropriateness for each context. Gathering across these types of interviews enabled triangulation of data across methods. Results from the qualitative analysis were used to inform quantitative data collection and analysis, which employed a follow-up survey focused on risk and protective factors identified in qualitative findings. The various sources of data mutually informed and reinforced each other throughout the iterative data analysis process (Creswell & Clark, 2017). This study focuses on data related to family protective factors, and in particular, family communication.

Data collection

We obtained Institutional Review Board and tribal approval prior to commencing the study. With the assistance of agency leaders and cultural insiders (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019), we recruited participants using flyers (posted online and distributed in person) and word of mouth. The first author collected the data. To increase cultural sensitivity, all who agreed to participated were given the option of being interviewed by a tribal interviewer (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019), but an interviewer from outside of the tight-knit communities was preferred. Qualitative data collection included 254 individual interviews, 64 family interviews (with 163 participants), and 27 focus groups (with 217 participants). Interviews followed a culturally-congruent life history approach (Burnette et al., 2014; Carspecken, 1996; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). A semi-structured interview guide, developed with the assistance of cultural insiders at a fifth-grade comprehension level, was used for all forms of qualitative data collection. This guide included questions such as: “Describe what you remember about growing up in your family; Whom did you go to for support? Describe a hard time growing up and how your family responded to that challenge; What helped you get through this challenge? How did your family communicate or talk to each other? Did people talk about how they felt? Describe what you think is a strong or resilient family today.” For their participation in individual interviews, participants received a $20 gift card to a local department store and a copy of their transcript; families interviewed received a $60 gift card.

Regarding rigor, more than half of participants participated in more than one form of qualitative data collection, such as a family or individual interview. Interviewing participants multiple times is one way of triangulating data and is recommended as a means of gaining more representative responses as it allows researchers to assess consistency of responses across time points (Carspecken, 1996). However, each respondent, or source, was only “counted” one time so as not to skew results, regardless of how many times they were interviewed.

For quantitative data collection, members of both tribes (including, but not limited to, qualitative participants) were invited to participate in an online survey (through Qualtrics). Survey participants were entered in a drawing for gift cards in the amount of $50, with over half selected to receive one. A total of 161 people started the survey, and 127 (80%) completed it. Table 1 provides participant demographics.

TABLE 1.

Primary data: qualitative and quantitative participant demographics

| Participant demographics | Qualitative (n = 436) | Quantitative (n = 127) |

|---|---|---|

| Inland Tribe | 228 (52.3%) | 80 (63.0%) |

| Coastal Tribe | 208 (47.7%) | 47 (37.0%) |

| Men | 149 (33.9%) | 23 (19.1%) |

| Women | 287 (65.8%) | 104 (81.9%) |

| Age (range = 21–80 years) | M = 39.7 | M = 46 |

| Married | 126 (28.9%) | 51 (40.2%) |

| Number of children (range = 0–14) | M = 2.55 | M = 3.77 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 78 (25.4%) | 12 (9.5%) |

| High school or equivalent | 69 (22.5%) | 18 (14.2%) |

| Some college/vocational degree | 69 (22.5%) | 28 (22.1%) |

| Associate’s | 47 (15.3%) | 27 (21.3%) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 44 (14.3%) | 26 (20.5%) |

| Household | ||

| Single | 15 (11.8%) | |

| Couple | 20 (15.7%) | |

| Single-parent | 25 (19.7%) | |

| Two-parent | 49 (38.6%) | |

| Blended/Extended | 18 (14.2%) | |

| Full-time employment | 85 (66.0%) | |

| Fairly difficult to pay bills | 69 (54.3%) | |

| Annual household income | ||

| <$15,000 | 18 (14.2%) | |

| $15,001–$25,000 | 21 (16.5%) | |

| $25,001–$50,000 | 39 (30.7%) | |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 22 (17.3%) | |

| >$75,001 | 27 (21.3%) | |

| Community type | ||

| Reservation/tribal communities | 105 (82.7%) | |

| Nearby/off-reservation | 15 (11.8%) | |

| Out-of-state | 7 (5.5%) | |

| Family Resilience | M (SD) = 18.2 (2.2) | |

| Life Satisfaction | M (SD) = 24.2 (6.6) | |

| Relationship Quality | M (SD) = 4.0 (0.7) | |

| Community and Social Support | M (SD) = 47.4 (7.8) | |

| Enculturation | M (SD) = 4.17 (0.8) | |

Note: Extended families include grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, etc. Blended families include stepparents and stepchildren. Adapted table reprinted with permission from McKinley and Miller Scarnato (2020).

Abbreviations: M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Qualitative data analysis

We used team-based analysis methods to analyze qualitative data (Guest & MacQueen, 2008), with tribal and non-tribal research assistants as team members. We employed a professional service to transcribe all interviews, which were processed in NVivo for analysis. Team members then conducted reconstructive analysis to inductively identify themes in qualitative data, proceeding through the following steps: (1) listen to/read interview transcripts multiple times; (2) create a hierarchical coding scheme using low-level coding; (3) analyze explicit and implicit meanings to develop a final coding scheme used to code all data. To assess inter-rater reliability, we calculated Cohen’s kappa coefficients (McHugh, 2012), finding them very high (.90 or higher). In our qualitative results, we present unifying themes identified across tribes and participants.

For member checking, all participants received a summary of results with an invitation to modify or add to findings. We found broad support for the findings through this process. The PI also disseminated a summary of results through community dialogues, tribal councils and committees, agencies, and trainings on more than 10 occasions. Peer debriefing with all team members occurred weekly throughout the data collection and analysis phases.

Quantitative data analysis

This inquiry focused on the relationship between protective factors (community and social support, relationship quality, and life satisfaction) and family resilience. The Family Resilience Inventory (FRI, α = .88) was used to assess family resilience. Example yes/no items include: “We express love and affection freely; Adult arguing is kept away from children; We come together during hard times, rather than going our separate ways” (see Appendix). The Social Support Index (SSI, α = .75) assessed community and social support through Likert-scale items such as: “People in this community are willing to help; I have friends who let me know they value who I am.” Relationship Quality (RQ) scales (α = .92) gathered Likert-scale responses to items such as: “In your current relationship, how often do you feel love? Supported? Respected? Understood?” The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS, α = .90) assessed life satisfaction through Likert-scale responses to items such as: “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal; I am satisfied with my life.” Adding to rigor, two of the measures used – the FRI and relationship quality scales – were developed through our qualitative research with the two focal tribes, and demonstrated high reliability (Burnette et al., 2020). Both instruments were systematically developed based on the most frequently cited promotive factors as they relate to family resilience and relationship quality. See Burnette et al. (2020) for a detailed explication of the process for development and validation. The FRI incorporates family communication as a protective factor (i.e., We express love and affection freely [hugs, kisses, saying “I love you”]). We were only missing data from one participant for the focal variables. For the participants who did not have a partner the items relating to relationship quality items were not applicable. These cases were missing at random, and as such we used listwise deletion (Kang, 2013). The final sample included in the regression analysis includes 101 participants. We examined variance inflation factors (VIFs) and detected no problems with multicollinearity among independent variables. We used SPSS Version 27 to perform all analyses. First, we calculated descriptive statistics for participants in both tribes (see Table 1).

Next, we examined bivariate relationships across the independent variables of social and community support, relationship quality, life satisfaction, and the dependent variable of family resilience. Our initial regression models included demographics (e.g., age, gender, income, marital status, and education) and other variables (i.e., enculturation). Due to limited sample size, variables were excluded from the final model in a step-wise fashion to create a parsimonious multivariate model that included only those variables significantly correlated (p < .05) with our outcome variable of family resilience. We used linear regression to analyze the multivariate main effects of our predictor variables.

QUALITATIVE RESULTS

To understand the role of communication as it relates to family resilience, results indicate that Indigenous families practice open communication to work through problems and challenges. In many cases, communicating with family members as a means of managing conflict demonstrated a conscious departure from the communication norms in their families of origin. The following themes related to family communication as a component of family resilience emerged from this analysis: (a) “It’s in the Family Circle”: Discussing Problems as a Family with the subtheme: Honesty between Partners; (b) “Never Bring Adult Business into Kids’ Lives”: Keeping Adult Conversations Private; and (c) “Trust Us Enough to Come to Us”: Open Communication between Parents and Children. For each quote included, we provide the tribal affiliation, gender, and participant category (focus group, family interview, or individual interview) for reference. Codes related to family communication appeared in the data 205 times. With regard to sources, each data collection type (i.e., individual interview, focus group, family interview) is considered a unique source, and codes related to family communication appeared across 137 unique sources (63 in the Inland Tribe, 74 in the Coastal Tribe). Thus, across the various forms of qualitative data collected, statements describing family communication as a component of family resilience were salient in both tribes. Our focus now turns to the identified themes.

“It’s in the family circle”: Discussing problems as a family

Participants in both tribes emphasized the importance of talking about problems openly as a family. Several participants described family meetings that were held for this purpose. A man from the Inland Tribe explained how problems are discussed within his family:

If one thing is wrong, you know with children, you sit them down and talk about your problems, and I guess, you know, nowadays we can. People used to sit around the table at times and discuss their days, what they did during the day, and what’s going to come, what happened that day, or something like that – have a family meeting and everything. I think that’s family values, you know, keeping it strong. Keep everybody on the right foot. … Whatever problems that you have, you’re not supposed to be afraid to talk about, you know, what’s in your family, because you all grew up with each other and there is some stuff that you can’t hide away. It’s in the family circle.

For this participant, strong families were characterized by open communication. In a focus group with Coastal Tribe members, a man described a similar view on healthy families, stating:

Being able to talk to each other. There should be no secrets in family. Everybody makes mistakes. Everybody falls short. You have to be able to come to your family whenever you do wrong and trust that they’re going understand and help you through whatever you’re going through.

Another focus group participant agreed, describing how he confides in “My favorite uncle.” He elaborated, “Anytime I go to him for help or anything because he always understands.” A young man from the Coastal Tribe described discussing problems with his parents, stating: “It feels like group discussion, if there’s something going on. I’ll bring it up, and we’ll all three [he and his parents] talk about it.” A professional man from the Inland Tribe also used the term “open discussion” when describing how his family approaches problems, as stated:

Going to someone else’s house, cooking, you know, traditional foods and all sorts. It’s been a big help to me. If there’s, if anybody has a problem, it’s kinda like an open discussion almost, you know? We try to problem solve with each other.

For one woman, such open discussions were seen as the biggest difference from her family of origin to her current family, as stated: “We talk to our children. We have family meetings.”

Maintaining open communication amongst family members was frequently described by participants across the life course as a way to manage problems that arose. An elder woman from the Coastal Tribe explained, when healthy families go through challenges, “They talk about it and find some kind of solution.” A teenage girl from the Coastal Tribe echoed, “We just stick together and it [the problem] brings us closer, or we talk it out and we try to fix it.” Having an open family discussion helped one family repair the damages to family relationships they experienced after the loss of their father, as a woman from the Coastal Tribe described in a family interview:

My dad was the glue that held our family together. When he died, we all scattered…When I had enough of all of it, I went to my oldest brother. I told him, I said, “You’re the oldest one.” I said, “You need to find a way to put our family back together.” I said, “We were so close before Daddy died. Now that Daddy’s dead, we ain’t worth a hill of beans.” I said, “You’re the oldest. You need to do something.” He said, “Okay, we’re going to do something. We’re going to call a meeting.” We called a meeting and put everything on the table. I told them what I heard was being said about me and my sister said what was being said about her. We put everything on the table and then it was over. Then we got close again. We’re still close today.

In addition to discussing problems and challenges, some participants emphasized the importance of humor and laughter in their communication with family members. In a focus group with the Inland Tribe, a woman described healthy families as follows:

They get together and they talk and they communicate. And they’re not so much critical, but you know, they they’re kind of telling the truth without bearing down on that person. They, um, give them a helping hand and, um, encouragement. And that’s the positive families that I’ve seen. And they you know, there’s times to, to listen, there’s times to talk, but then, a majority of the time, they’re all laughing. And they’re just kind of just, just sitting there and being a family.

A teenage girl from the Inland Tribe characterized how her family communicated, as stated, “Laugh, carry-on, and we just talk.” The participant added that when problems arose, “We don’t stay mad at each other. The next minute or so we’ll be talking, laughing together.” She went on to explain: “When we’re arguing we just sit in the living room so then one of them will bring up the conversation and we start talking about it and we laugh. And we forget about it, just like that.” In the words of a young woman from the Inland Tribe, participants across both tribes described managing conflict and resolving problems in their families through “basically open talking and stuff and trust.”

Honesty between partners

Participants often discussed problems that arose in their romantic relationships and stressed the importance of honest communication to work through them. After surviving hard times in their marriage, including infidelity, a Coastal Tribe woman emphasized in a family interview, “Communication. I say always be honest about everything. It doesn’t matter. Whatever your heart is feeling, be honest about it. Talk about it.” During arguments, her husband thought it was important to, “Let it cool down. I’ll walk away sometimes. I never put my anger on her. Never. I walk away.”

Several participants explained the importance of communicating calmly as a couple, even in times of difficulty. As one woman from the Coastal Tribe stated: “This is how we solve our problems. If we’re in some kind of argument we’re not going to holler. I’ll sit there, and I’ll look at him and I’ll try and explain.” Another woman from the Coastal Tribe described resolving an argument with her partner:

Saturday is whenever we really talked about everything, ‘cause it happened Wednesday night, and then Saturday is whenever we really talked about it… It really ended up good…We talked about everything that we could remember about the argument, and what brought it [the argument] on. It really ended well.

A man from the Inland Tribe described talking about problems as helping with stress management:

It [talking] releases some of the stress. Me and [partner] when we would go home, when we’ve had a bad day, we tell each other. Releasing the tension, I guess. Also, when you hold it in, sometimes you might explode. It’s going to make your relationship worse.

When discussing problems within their relationships, participants in both tribes stressed the importance of honest, calm communication as a means of promoting a healthy relationship.

“Never bring adult business into kids’ lives”: Keeping adult conversations private

While discussing challenges and problems was an important way for families to work through them, participants in both tribes also described the need to keep adult conversations private as a means of protecting children. Parents explained that they made efforts to have arguments or heavy discussions when children were asleep or not around. A woman from the Inland Tribe shared:

We’ve [she and partner] talked once a month. Our kids sleep in and we’re outside smoking our cigarette. We’ll sit there and talk. He points out what my problem needs to be adjusted and then I point out his and we work it out.

Similarly, a woman from the Coastal Tribe reflected:

My kids, they don’t know the whole story you know. You and I [adults] had something to say, we always wait until the kids wasn’t there, you know. That’s one thing I never did was try to [have an] argument in front of the kids.

Parents needed to have these discussions, but waited until they could do so in private, as an Inland Tribe mother explained in a family interview:

They [children] really don’t know when we’re arguing, or if we were to because we try not to do it in front of them. I mean, they probably can’t tell you themselves that, that they don’t, they don’t know that. And if there was something to come up, it’s like when all the kids are sleeping, that’s when we’ll start talking about it at times.

Echoing this, many participants reflected that they had never seen their parents arguing. A professional woman from the Coastal Tribe described her parents’ relationship as: “Very good. I’ve never even heard my mom and my dad argue.” When asked whether she thought they had disagreed, she replied:

I’m sure they did, but my dad made it a point. He always said that he would never bring adult business into kids’ lives…I’m sure they had disagreements in 30 years, but that’s nothing that they brought up in front of us.

A man from the Inland Tribe recalled seeing, but not hearing, his parents’ adult conversations:

If there was [sic] decisions to be made, we always…saw them [parents] sitting at the table. So, I knew they were discussing something that was supposed to be adult. Mom would, used to say, “Go and play,” you know, “Don’t bother us if we’re at the table. Were just discussing on how we need to handle this.”

A woman from the Coastal Tribe explained how her mother and father kept conversations about the stressors of daily life private:

She [mother] told us, as we got older, that they communicated when we went to bed or when we went to school, in private in their room. They never brought it, if there was no food for tomorrow or no money for tomorrow, we didn’t know nothing about that ‘cause they always communicated in private. We never knew no argument. No issues in the house. I was like, “That’s weird.” They always communicated when we weren’t home or either sleeping or in their private room, private area.

A woman from the Inland Tribe was grateful that her parents took a similar approach, stating:

I was like, “I know you have fought” …I was like, “I know you argued” and I was like, “You can’t be with somebody that I love and not argue.” I don’t remember them arguing and I think if they did, they waited until we were asleep or somebody else watched us and I appreciate that.

Being shielded in this way from her parents’ arguments helped one Inland Tribe woman to develop healthy communication patterns in her adult relationship. She explained:

I never saw my mom and dad argue. I never saw them argue…Every once in a while, she’d [mom] put all of us, whoever was home, outside, and they’d tell us not to come back in until they allowed [us] back in.…We thought they must be arguing, but never did it in front of us, and that’s how I grew up. … When we were older, we saw them disagree and stuff, but they weren’t fighting people, and so different from my husband. That’s how he grew up, his mom and dad fighting and arguing. It was ugly on their side. After we got married, he would argue with me…It was so strange to me. I’m like, “Why are you doing that? Our son’s here.” He didn’t understand that because that’s how he grew up.

As these participants described, parents often intentionally discussed adult problems in private to protect children.

“Trust us enough to come to us”: Open communication between parents and children

In addition to communicating about conflict and challenges within the family system, participants across both tribes gave special attention to the importance of fostering trust and open communication between parents and children. A professional woman from the Inland Tribe described how she and her husband encourage their children to come to them with problems: “I tell my babies. I said, ‘Trust me enough. Trust Dad enough.’ Like you know you’re not supposed to do something but you do it anyways, I said, ‘Trust us enough to come to us.’” A woman from the Coastal Tribe reflected on how her parents demonstrated their trust in her, stating:

They’ve always been there for me. … I talk to my mom a lot, but they would let me make my own decisions. They would tell me how they felt about it, but I was still grown up, so it was me to make my own decisions whether it was right or wrong.

Children in these communities were seen as valued family members who have a voice in family decisions, as a woman from the Coastal Tribe explained:

How I was raised that it was just my parents spoke to me. My parents didn’t just put me in front of a TV. They treated me as a person, not as just a toy or just an accessory. I was a person of the household and that’s the way I treat my children. They have a voice. They have a voice on what we’re having for dinner tonight.

A woman from the Inland Tribe encouraged her children to be honest with her, even when that meant offering a critique, as stated: “I always tell them, ‘If you wanna say things, say it. You don’t like the things I’m doing, tell me.’” An elder man from the Inland Tribe explained in a family interview how maintaining open communication with his children helped him to guide them as a parent:

When we ate we all talked and let the kids tell us what they done; if they wanted something to talk about they’re free to talk about it. I call that round table discussion. We all talk and kids, when they eating [sic], they just talk away. They talk about anything they want. One of them did something and we didn’t know nothing about, they would tell. And we would ask, “Why’d you do it?” They’d make some kind of excuse…but we knew about it so it’s a “Well, don’t do it anymore,” you know, and all that. And that would be over…. free to talk about it and encourage them not to do it and stuff like that.

Similarly, an Inland professional woman described the trust she shares with her children:

They have to weather their own situations. … when they call and say “This happened to me. I don’t want you to hear it from [someone else].” And that’s very important to them also. If something happens to them they know I want a call first to let me know. I know, they don’t want to let me hear it from another person, so.

For one mother from the Coastal Tribe, it was important that her children could go to other family members if they didn’t feel comfortable talking with her, as stated:

Just to have open communication was a big thing for us. Is it so much now? Probably not because they just don’t want to come to mama with everything. I know some of the things that they didn’t come to me, other family members were there. But at least knowing that they could. And even if it was something and they would come to me and say, “I want to talk to somebody and I don’t feel comfortable talking to you.” I would find someone for them.

As these participants’ quotes demonstrate, trust and communication between parents and children were considered fundamental parts of their relationship.

Participants in both tribes also described how parents being understanding and open with their children helped foster trust and honesty. As one mother from the Inland Tribe explained:

I’ve told them [children] about my life … And I don’t want them to do the mistakes that I’ve made. Because I talk to them all the time, so, they’re pretty much, “Mom, we know.”—“I know you know about this stuff, I tell you all.” … I don’t hide nothing from them. I tell them everything. Because I never had that relationship with my mom, so that’s one of the things that I was going to do different. Just show them, and tell them stuff, you know.

Similarly, a woman from the Coastal Tribe described her father’s communication with her: “My dad is very open. My dad’s honest. He’ll talk about all kinds of stuff.” As a Coastal Tribe mother explained, no topic was off limits or hidden from children:

We’re very open with them about a lot with them. I think that’s another thing too, I don’t know really how to sugar-coat, so, I think, for their age we kind of just discuss whatever topic they bring up. We kind of inch around it, but we’re very open and everything with them.

Parents’ openness with their children allowed them to speak from experience about the challenges and difficulties their children might face in the future. An Inland mother shared how she tries to help her children learn from her experiences:

I was a teen mom. I had him at 17. So, that was one of the lessons learned in my life, from having to grow up quick…I put that on them. You know, I don’t want you to—the mistake, I’m not saying that he’s a mistake but you know. That having to grow up…the choices we make in life and the consequences you pay later…he sees that so, he’s probably tired of hearing me - Coming, repeating the same thing over and over, but I drill it in them, just so they know.

This participant also experienced IPV, and added: “I’ve been in that uh, position with their dad. Being a victim and stuff.” She tried to transmit nonviolent values to her children. She added that her son,

You know, I had to go through that and so…I don’t want, as a man, my son, I don’t want him to treat anybody that way [become violent]. As a daughter, I don’t want her to be a victim of you know, this is not what this is. You know, that’s not love, you know, stuff like that. So, I try to kind of pass all those things down.

This woman shared these experiences with her children as a means of shielding them from harm. A teenage girl from the Inland Tribe expressed her appreciation for her mother’s openness about unplanned pregnancies with her, as stated: “My mom, um, she always talked to me about it … I’ve talked to my other friends, and not a whole lot of parents kinda talk about it.” She went on to share how her mother talked to her about alcohol abuse: “My mom did tell me about drinking ‘cause my grandpa was an alcoholic.” Through open conversations about these topics, this mother helped her daughter understand how to prevent future problems.

Participants also described their parents as understanding, which helped foster honest communication with children. A teenage girl from the Coastal Tribe compared her dad’s communication style to her mom’s, as described:

At my dad’s house, he understands me more because of course, all parents go through my stage and want to be with their friends, and I guess he sees that now and I’ve talked to him multiple times, but with her, I can’t talk to her about that. If I talk to her, I end up getting screamed at or punished or some stupid lecture. With my dad, he gets on my level with me and he tries to talk to me. He lets me learn my lessons and everything.

Having open communication with her father helped this participant discuss problems with him without fear or punishment. A mother from the Inland Tribe explained how her sister helped her to have open conversation with her children, stating in a family interview:

I used to scream at my children. My sister told me, she said, “[Name], think of what you’re teaching your kids. You’re teaching your kids to scream at you. Yeah. Stop and talk to them.” I just started talking to them and things were so much better. We understood each other. We understood each other. Once the screaming was gone, we sat actually talked, we understood each other. I learned that from my big sister.

For participants in both tribes, open communication between parents and children helped to create healthy parent–child bonds characterized by honesty and trust.

Quantitative results

Regression results indicated that, as predicted, ecological promotive factors were associated with family resilience. We identify these as promotive factors as we are not conducting the mediational or step-wise analysis necessary to assess whether factors are protective. The model was significant and accounted for 36% of the variance (See Table 2). Results on average indicated that the Inland tribe was more likely to report higher family resilience (M = 44.3) than the Coastal Tribe (38.7), although this difference was not statistically significant when examined using t tests. Regression analysis indicates that higher community and social support, relationship quality, and life satisfaction were associated with greater family resilience, supporting our hypotheses. These results indicate that factors at the community, relational, and individual levels promote family resilience.

TABLE 2.

Regression model for predictors of family resilience

| Variable | B(SE) | Beta |

|---|---|---|

| Tribal affiliation | −1.51 (.55)** | −.24 |

| Community and social support | .12 (.04)** | .29 |

| Relationship quality | 1.2 (.38)** | .28 |

| Life satisfaction | .13 (.04)** | .27 |

| R2 | .36 | |

| F | 13.35*** |

Note: The Inland Tribe had higher overall resilience than the Coastal Tribe.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

DISCUSSION

This mixed-methods inquiry revealed Indigenous participants’ in-depth perspectives on family communication as an aspect of family resilience and identified statistically significant relationships between the predictor variables of social and community support, relationship quality, and life satisfaction and the outcome variable of family resilience. Taken together, these findings help researchers and practitioners understand how Indigenous families cultivate resilience through internal and external supports that span ecological levels (micro, mezzo, macro). Interpreting these findings through the lens of the FHORT fosters increased understanding of culturally-specific aspects of Indigenous families (i.e., open family communication patterns), the protective factors that promote family resilience (i.e., social and community support and relationship satisfaction), and the relationship between family members’ transcendence of historical oppression (i.e., life satisfaction) and family resilience.

Our qualitative findings demonstrate the important role that communication plays in fostering resilient Indigenous families. Participants in both tribes stressed the importance of open and honest communication across the immediate and extended family system. Consistent with the FRI which assess family resilience across generations, some participants explained that practicing open communication in their current families was a conscious departure from the lack of openness in their families of origin. From the perspective of the FHORT, this is likely due to the context of historical oppression that Indigenous peoples have endured. When Indigenous peoples were colonized and forcibly assimilated to Western culture, they endured the trauma of forced relocation and were prohibited from speaking their native languages (Haag, 2007). Surviving such experiences disrupted family communication patterns, as survivors may have found it too painful or risky to speak about them. Attesting to their resilience as a people, participants practice open communication in their families, in resistance to systematic efforts to silence Indigenous voices. The qualitative results of this study provide important empirical evidence of the proactive communication strategies Indigenous families employ to promote family resilience. These results offset negative and dehumanizing stereotypes that often misrepresent Indigenous peoples’ communication styles and family functioning.

Participants provided in-depth descriptions of how they practice open communication by holding family meetings to talk through problems, being honest in difficult conversations with their partners, and fostering trust and honesty in parent–child communication. Consistent with extant literature, family communication characterized by openness, honesty, and a willingness to have difficult conversations to address problems and challenges was an important aspect of family resilience for our participants (Keating et al., 2013; Lucas & Buzzanell, 2012; Saltzman, 2016). Research suggests that family meetings are a recommended, culturally-sensitive approach to addressing the healthcare needs of Indigenous families (McGrath et al., 2006). Talking through problems together as a family can bolster family resilience by facilitating meaning-making and collaborative problem-solving (Black & Lobo, 2008; Saltzman, 2016). From the perspective of the FHORT, the open family communication style described by participants is a culturally-relevant protective factor that helps foster family resilience.

Findings also demonstrated the following two prevailing perspectives on the value of parent–child communication: fostering trust and openness on the part of both parents and children, as well as keeping adult conversations and conflicts away from children. It seems that parents wanted their children to learn from parents’ experiences and feel comfortable talking with parents about their problems, while also establishing boundaries for how parents communicate in front of children to protect them from marital conflict. Through the lens of the FHORT, these findings show how parents attempt to balance the presence of risk and protective factors in the lives of their children to support their resilience. Adult arguments might pose a risk to children, while learning about parents’ experiences so as not to repeat their mistakes and being able to talk to parents about problems may play a protective role. Research suggests that arguing in front of children models maladaptive communication patterns that children may acquire (McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010). Existing literature has also shown that talking with parents about potential harms and risks protects Indigenous youth from adverse outcomes, including disease (Hennessy et al., 1999; Ramirez et al., 2002), substance use (Beebe et al., 2008; Urbaeva et al., 2017), and risky sexual behavior (Oman et al., 2006)

As hypothesized, quantitative findings support the notion that promotive factors at the community (social and community support), relational (relationship quality), and individual (life satisfaction) levels positively contribute to Indigenous family resilience. Consistent with extant research, these findings indicate that a family’s relationship to external support systems, as well as family members experiencing positive relationships with one another and oneself are associated with greater family resilience. From the relational perspective of the FHORT, family members reporting high life satisfaction may have transcended experiences of historical oppression, which is associated with greater resilience for the family system as a whole. These findings lend support to the FHORT’s multi-level and interactional view of family resilience.

Strengths, limitations, and future research

This study contributes important knowledge to the field of family resilience, offering context-specific insight into the role that family communication and multi-level promote factors play in cultivating Indigenous family resilience. These findings highlight culturally-specific aspects of and practices within Indigenous families that promote resilience, countering deficits-based perspectives and harmful stereotypes that perpetuate pathological view of Indigenous family functioning. This inquiry included the culturally grounded FHORT, developed and utilized though over a decade of work with the focal tribes, as well as the culturally grounded relationship quality scale and FRI (Burnette et al., 2020). These culturally grounded measures ensure higher validity as they were developed through extensive work with the focal tribes. Although the qualitative results focused on family communication as an aspect of family resilience, the other promotive and protective factors identified in quantitative results warrant special inquiry, namely social support, relationship quality, and life satisfaction. We were not able to qualitatively investigate these factors due to the breadth of qualitative data and space limitations, however future research should investigate these promising factors thoroughly.

The scope for this inquiry was limited to protective factors. Reporting protective factors does not negate or preclude a simultaneous or additional potential of risk factors with participants noting a lack of communication or other risks factors. However, these factors warrant a separate investigation due to their complexity and breadth. Results from convenience samples cannot be extended beyond their context, and though these findings may have theoretical relevance for other groups, they are not intended to be generalized. With the diversity across Indigenous nations, results could benefit from replication and examination across additional contexts for a broader understanding. The sample size was limited, impairing power to detect true significant relationships; a larger sample would likely yield more robust results in many of the preliminary relationships identified in this article. Moreover, both samples had more women than men, particularly the quantitative sample, which may have influenced results. Future inquiries that examine gender differences using samples with a more equal distribution of men and women may illuminate how gender interacts with focal variables. Variables and surveys were self-report measures rather than direct observations. This research was cross-sectional. Although it displays a snapshot of how people were coping and experiencing life at the time of data collection, it did not capture how people were faring over time, where longitudinal analysis would be helpful. Furthermore, this exploratory analysis did not utilize mediational analysis due to limited sample size, but future research can examine how adversity may affect the protective versus promotive effect of the focal variables predicting family resilience.

IMPLICATIONS.

According to the FHORT, despite experiencing historical oppression and intentional efforts to disrupt and undermine Indigenous family systems (Author[s], 2017), participants practiced open, healthy family communication patterns, contributing to family resilience. It is important to disseminate and normalize the prominence of healthy communication within Indigenous families to counter dominant discourses that pathologize Indigenous family systems. Moreover, broader community and social support from Indigenous family systems also contributed to family resilience (Burnette & Hefflinger, 2016). The quality of relationships along with feelings of transcendence promoted resilience for Indigenous families. In line with the FHORT (Burnette & Figley, 2017), ecological factors across community, relational, and individual levels are important to promote overall family resilience, which has important implications for health and well-being (Beebe et al., 2008; Hennessy et al., 1999; Oman et al., 2006; Ramirez et al., 2002; Urbaeva et al., 2017). Practitioners can focus on strengthening social supports to bolster such promotive factors and family resilience. Moving beyond micro systems to the meso layers of social context and beyond is needed to promote culturally relevant intervention and prevention programs to offset healthy inequities. These holistic interventions can seek to promote well-being among Indigenous youth and families. Community-based approaches that include the extended family system are integral to promote Indigenous family resilience. Moreover, clinical programs providing practical tools to foster healthy communication – both about difficult topics as well as positive topics – are promising avenues to foster healing and resilience (Burnette & Hefflinger, 2016).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the dedicated work and participation of the tribes and research assistants over the years who have contributed to this work. This work was supported by the Fahs-Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation Faculty Grant Program [grant number #552745]; The Silberman Fund Faculty Grant Program [grant #552781]; the Newcomb College Institute Faculty Grant at Tulane University; University Senate Committee on Research Grant Program at Tulane University; the Global South Research Grant through the New Orleans Center for the Gulf South at Tulane University; The Center for Public Service at Tulane University; Office of Research Bridge Funding Program support at Tulane University; and the Carol Lavin Bernick Research Grant at Tulane University. This work was also supported, in part, by Award K12HD043451 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (Krousel-Wood-PI; Catherine McKinley (Formerly Burnette).-Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH). Scholar).; and by U54 GM104940 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, which funds the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AA028201). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding information

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grant/Award Number: K12HD043451; Fahs-Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation, Grant/Award Number: 552745; National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Grant/Award Number: U54 GM104940; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Grant/Award Number: R01AA028201; Silberman Fund Faculty Grant Program, Grant/Award Number: 552781

APPENDIX A.: THE FAMILY RESILIENCE SCALE

Instructions: Please indicate whether the following things are generally true for your family (0 = no; 1 = yes). Family is defined by you and may include parents, grandparents, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins, and adopted family members.

In my current family unit:

We know what is expected of each other

Education is valued

We express love and affection freely (hugs, kisses, saying “I love you”)

We laugh a lot

We have a lot of family time together (doing activities, eating, spending quality time)

Adult arguing is kept away from children

I feel it is stable, safe, and predictable

We have family members to look up to (role models)

We attend each other’s events and support each other in each other’s goals

We do not tolerate violence against any of its members.

We work together to help each other and to complete goals

We have strong values that guides our actions

We respect all members (including elders, women, men, and children)

We are close knit

We get together a lot for birthdays, holidays, meals, and special events

We use hard times to become stronger

We pass down cultural traditions

We prioritize children’s needs over adult needs

We come together during hard times, rather than going our separate ways.

We stick with each other through thick and thin

In my family growing up (during first 18 years of life):

We knew what was expected of each other

Education was valued

We expressed love and affection freely (hugs, kisses, saying “I love you”)

We laughed a lot

We had a lot of family time together (doing activities, eating, spending quality time)

Adult arguing was kept away from children

I felt it was stable, safe, and predictable

We had family members to look up to (role models)

We attended each other’s events and support each other in each other’s goals

We did not tolerate violence against any of its members.

We worked together to help each other and to complete goals

We had strong values that guides our actions

We respected all members (including elders, women, men, and children)

We were close knit

We got together a lot for birthdays, holidays, meals, and special events

We used hard times to become stronger

We passed down cultural traditions

We prioritized children’s needs over adult needs

We came together during hard times, rather than going our separate ways.

We stuck with each other through thick and thin

These two scales can be used individually or in conjunction with each other to identify inter-generational patterns.

Scoring: Add responses for each item. Total scores range from 0–20, with higher scores indicating a higher degree family resilience. Each of the items can be thought of as a protective factor, cumulatively contributing to the holistic measure of family resilience (Burnette et al., 2020).

Footnotes

ETHICS STATEMENT

Research study activities were reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional review board/ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with existing ethical standards. All participants gave their informed consent or assent, where appropriate, prior to their inclusion in the study.

REFERENCES

- Acuña MA, & Kataoka S (2017). Family communication styles and resilience among adolescents. Social Work, 62(3), 261–269. 10.1093/sw/swx017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe LA, Vesely SK, Oman RF, Tolma E, Aspy CB, & Rodine S (2008). Protective assets for non-use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs among urban American Indian youth in Oklahoma. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 12(1), 82–90. 10.1007/s10995-008-0325-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutel ME, Glaesmer H, Wiltink J, Marian H, & Brähler E (2010). Life satisfaction, anxiety, depression and resilience across the life span of men. The Aging Male, 13(1), 32–39. 10.3109/13685530903296698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black K, & Lobo M (2008). A conceptual review of family resilience factors. Journal of Family Nursing, 14(1), 33–55. 10.1177/1074840707312237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE (2016). Historical oppression and Indigenous families: Uncovering potential risk factors for Indigenous families touched by violence. Family Relations, 65(2), 354–368. 10.1111/fare.12191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE (2018). Family and cultural protective factors as the bedrock of resilience and growth for Indigenous women who have experienced violence. Journal of Family Social Work, 21(1), 45–62. 10.1080/10522158.2017.1402532 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, Boel-Studt S, Renner LM, Figley CR, Theall KP, Miller Scarnato J, & Billiot S (2020). The family resilience inventory: A culturally grounded measure of current and family-of-origin protective processes in Native American families. Family Process, 59(2), 695–708. 10.1111/famp.12423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, & Figley CR (2017). Historical oppression, resilience, and transcendence: Can a holistic framework help explain violence experienced by Indigenous people? Social work, 62, 37–44. 10.1093/sw/sww065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, & Hefflinger T (2016). Honoring resilience narratives: Protective factors among Indigenous women experiencing intimate partner violence. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 21(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, Renner LM, & Figley CR (2019). The framework of historical oppression, resilience and transcendence to understand disparities in depression amongst Indigenous peoples. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(4), 943–962. 10.1093/bjsw/bcz041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, Roh S, Liddell J, & Lee YS (2019). The resilience of Indigenous women of the US who experience cancer: Transcending adversity. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 30, 1–16. 10.1080/15313204.2019.1628680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, Sanders S, Butcher HK, & Rand JT (2014). A toolkit for ethical and culturally sensitive research: An application with Indigenous communities. Ethics and Social Welfare, 8(4), 364–382. 10.1080/17496535.2014.885987 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carspecken PF (1996). Critical ethnography in educational research: A theoretical and practical guide. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Clark VLP (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Grevenstein D, Bluemke M, Schweitzer J, & Aguilar-Raab C (2019). Better family relationships—higher well-being: The connection between relationship quality and health related resources. Mental Health & Prevention, 14, 200160. 10.1016/j.mph.2019.200160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, & MacQueen KM (2008). In Guest G & MacQueen KM (Eds.), Handbook for team-based qualitative research. Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haag AM (2007). The Indian boarding school era and its continuing impact on tribal families and the provision of government services. Tulsa Law Review, 43(1), 1–20 https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol43/iss1/8 [Google Scholar]

- Hawley DR (2013). The ramifications for clinical practice of a focus on family resilience. In Becvar DS (Ed.), Handbook of family resilience (pp. 31–50). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy CH, John R, & Anderson LA (1999). Diabetes education needs of family members caring for American Indian elders. The Diabetes Educator, 25(5), 747–754. 10.1177/014572179902500507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ka’apu K, & Burnette CE (2019). A culturally informed systematic review of mental health disparities among adult Indigenous men and women of the USA: What is known? The British Journal of Social Work, 49(4), 880–898. 10.1093/bjsw/bcz009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H (2013). The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 64(5), 402–406. 10.4097/kjae.2013.64.5.402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating DM, Russell JC, Cornacchione J, & Smith SW (2013). Family communication patterns and difficult family conversations. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 41(2), 160–180. 10.1080/00909882.2013.781659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas K, & Buzzanell PM (2012). Memorable messages of hard times: Constructing short-and long-term resiliencies through family communication. Journal of Family Communication, 12(3), 189–208. 10.1080/15267431.2012.687196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, & Monn AR (2015). Child and family resilience: A call for integrated science, practice, and professsional training. Family Relations, 64(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS (2018). Resilience theory and research on children and families: Past, present, and promise. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 12–31. 10.1111/jftr.12255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath P, Patton MA, Holewa H, & Rayne R (2006). The importance of the ‘family meeting’ in health care communication with Indigenous people: Findings from an Australian study. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 12(1), 56–64. 10.1071/PY06009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh ML (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282 https://hrcak.srce.hr/89395 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, Figley CR, Woodward SM, Liddell JL, Billiot S, Comby N, & Sanders S (2019). Community-engaged and culturally relevant research to develop behavioral health interventions with American Indians and Alaska Natives. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 26(3), 79–103. 10.5820/aian.2603.2019.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, Ka’apu K, Miller Scarnato J, & Liddell J (2020). Cardiovascular health among US Indigenous peoples: A holistic and sex-specific systematic review. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 17(1), 24–48. 10.1080/26408066.2019.1617817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, Lesesne R, Temple C, & Rodning CB (2020). Family as the conduit to promote Indigenous women and men’s enculturation and wellness: “I wish I had learned earlier”. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 17(1), 1–23. 10.1080/26408066.2019.1617213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, & Miller Scarnato J (2020). What’s love got to do with it? “Love” and alcohol use among US Indigenous peoples: Aligning research with real-world experiences. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 30, 1–21. 10.1080/15313204.2020.1770650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, Miller Scarnato J, Liddell J, Knipp H, & Billiot S (2019). Hurricanes and Indigenous Families: Understanding connections with discrimination, social support, and violence on PTSD. Journal of Family Strengths, 19(1), Article 10. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol19/iss1/10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, Miller Scarnato J, & Sanders S (2020). Why are so many Indigenous peoples dying and no one is paying attention? Depressive symptoms and “loss of loved ones” as a result and driver of health disparities. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. 10.1177/0030222820939391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, Roh S, Lee YS, & Liddell J (2020). Family: The bedrock of support for American Indian women cancer survivors. Family & Community Health, 43(3), 246–254. 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, Spencer MS, Walters K, & Figley CR (2020). Mental, physical and social dimensions of health equity and wellness among US Indigenous peoples: What is known and next steps. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 30, 1–12. 10.1080/15313204.2020.1770658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CB, & Hembree-Kigin TL (2010). Marital conflict. In Parent-child interaction therapy (pp. 329–340). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Oman RF, Vesely SK, Aspy CB, Tolma E, Rodine S, Marshall L, & Fluhr J (2006). Youth assets and sexual abstinence in Native American youth. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 17(4), 775–788. 10.1353/hpu.2006.0133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JR, Crano WD, Quist R, Burgoon M, Alvaro EM, & Grandpre J (2002). Effects of fatalism and family communication on HIV/AIDS awareness variations in Native American and Anglo parents and children. AIDS Education and Prevention, 14(1), 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh S, McKinley CE, Liddell JL, Lee YS, & Yun Lee H (2020). American Indian women cancer survivors’ experiences of community support in a context of historical oppression. Journal of Community Practice, 28(3), 265–279. 10.1080/10705422.2020.1798833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman WR (2016). The FOCUS family resilience program: An innovative family intervention for trauma and loss. Family Process, 55(4), 647–659. 10.1111/famp.12250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani S, Jokar B, & Sahragard N (2007). Effects of resilience on mental health and life satisfaction. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 13(3), 290–295 http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-275-en.html [Google Scholar]

- Stiffman AR, Brown E, Freedenthal S, House L, Ostmann E, & Yu MS (2007). American Indian youth: Personal, familial, and environmental strengths. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(3), 331–346. 10.1007/s10826-006-9089-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Theiss JA (2018). Family communication and resilience. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 46(1), 10–13. 10.1080/00909882.2018.1426706 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M (2016). Varied patterns of family resilience in challenging contexts. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 42(1), 19–31. 10.1111/jmft.12124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbaeva Z, Booth JM, & Wei K (2017). The relationship between cultural identification, family socialization and adolescent alcohol use among Native American families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(10), 2681–2693. 10.1007/s10826-017-0789-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waller MA (2001). Resilience in ecosystemic context: Evolution of the concept. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(3), 290–297. 10.1037/0002-9432.71.3.290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F (2016). Applying a family resilience framework in training, practice, and research: Mastering the art of the possible. Family Process, 55(4), 616–632. 10.1111/famp.12260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Beltran R, Huh D, & Evans-Campbell T (2011). Dis-placement and dis-ease: Land, place, and health among American Indians and Alaska Natives. In Communities, Neighborhoods, and Health (pp. 163–199). Springer; 10.1007/978-1-4419-7482-2_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]