Abstract

A thrombosed giant aneurysm of the V1 and V2 segments of the vertebral artery (VA) is rare. Therefore, there is controversy regarding its optimal treatment. A case of a symptomatic giant VA aneurysm located in the V1 to V2 segments on the left treated successfully by endovascular trapping of the VA is reported. A 68-year-old woman presented with swelling in the left anterior neck. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed a giant aneurysm measuring 47 × 58 × 47 mm3 in the left neck. Ten days after her first visit, she presented with sudden onset of left anterior neck pain. Repeated CTA showed a partial thrombus in the aneurysm. Angiography showed two thrombosed giant aneurysms located in the V1 to V2 segments of the left VA. After endovascular trapping for the aneurysms, the anterior neck pain resolved and the aneurysm gradually shrank. This case demonstrates that endovascular surgery is better than open surgery because it is less invasive. When performing endovascular treatment, trapping will be an alternative strategy for a symptomatic giant thrombotic aneurysm of the V1 and V2 segments of the VA if the patient can tolerate ischemia.

Keywords: endovascular treatment, extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm, giant, thrombosed, trapping

Introduction

A thrombosed giant aneurysm of the V1 (pre-foraminal segment: origin to the transverse foramen of C6) and V2 (foraminal segment: from the transverse foramen of C6 to the transverse foramen of C2) segments of the vertebral artery (VA) is rare. Most lesions have been caused by trauma.1) Other etiologies include atherosclerosis, syphilis, rheumatoid arthritis, neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), collagen disease, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, Marfan’s disease, Behçet’s disease, and iatrogenic.2–5) When the aneurysm ruptures, the prognosis is poor.6–8) Therefore, earlier diagnosis and treatment are required. Regardless of trapping and ligation combined with bypass surgery,9,10) endovascular trapping,8) proximal occlusion,11) and flow diverter stent placement,12,13) the appropriate surgical treatment for an extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm (VAn) has not yet been established.

A case of symptomatic thrombosed giant unruptured aneurysms located in the V1 to V2 segments of the left VA treated successfully by endovascular trapping of the VA is reported.

Case Presentation

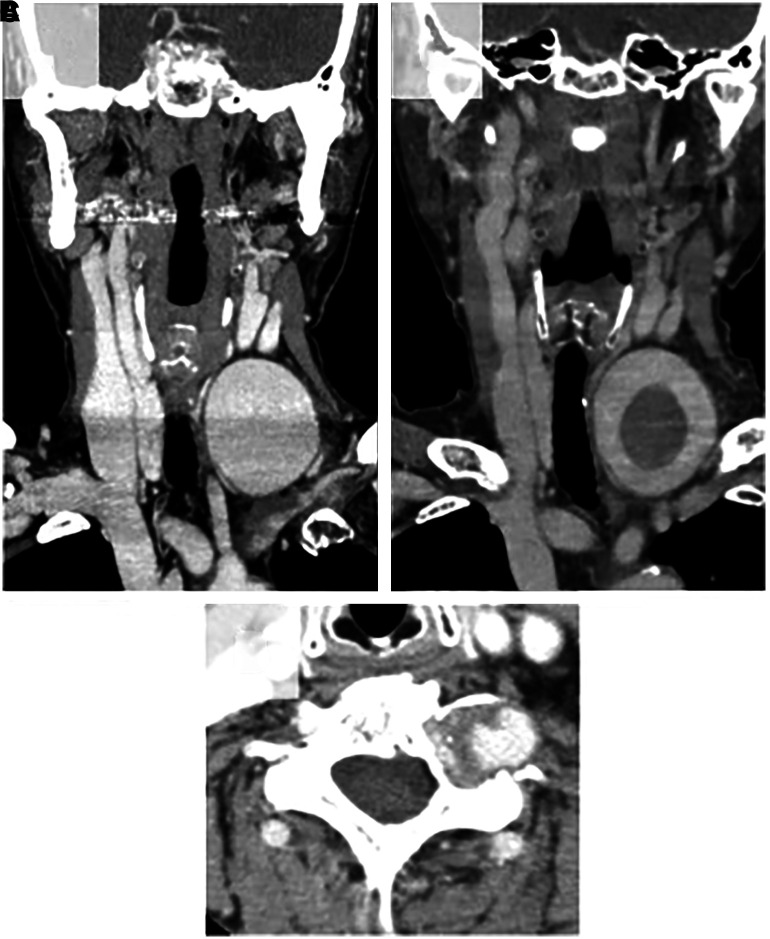

A 68-year-old woman without any relevant medical, traumatic, neck surgery, or family hereditary disease history visited our hospital due to swelling in the left anterior neck. On physical and neurological examination, a painless pulsatile mass was found in the left anterior neck, and no neurological deficit was found. She had no serological abnormalities including white blood cell (WBC) count and C-reactive protein (CRP). Her blood coagulation tests showed mildly elevated d-dimer (1.6 μg/mL) and normal fibrinogen levels (354 mg/dL). Computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed a giant aneurysm measuring 47 × 58 × 47 mm3 in the left neck (Fig. 1A). CT showed bone erosion of the left transverse foramen at the C6 level (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Initial coronal CTA (A) showing a giant aneurysm of the V1 segment of the left vertebral artery. Axial CTA (B) showing bone erosion in the transverse foramen of the cervical vertebra. Repeated coronal CTA 10 days later (C) showing a thrombosed giant aneurysm of the left V1. CTA: computed tomography angiography.

Based on these findings, she was diagnosed as having an aneurysm in the V1 and V2 segments of the VA. Ten days after her first visit, she was brought to the emergency department with acute onset of left anterior neck pain. Repeated CTA showed that the aneurysm was partially thrombosed (Fig. 1C). Intimal flap, double lumen, pearl and string sign, and string sign were not found. The contrast medium did not leak from the aneurysm. Blood coagulation tests showed a prominent increase in d-dimer (9.5 μg/mL) and a decrease in fibrinogen levels (230 mg/dL).

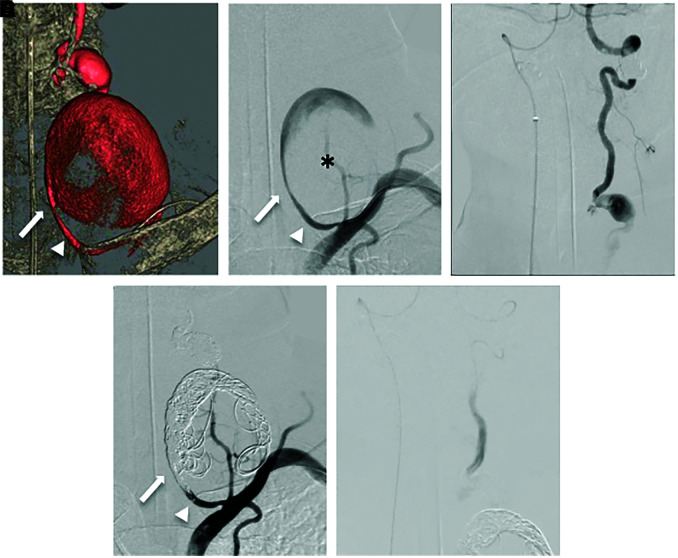

Endovascular treatment was performed under general anesthesia for the purpose of preventing rupture. A 5-Fr guiding catheter (Envoy MPC; Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, Fremont, CA, USA) was guided to the origin of the left VA via the left brachial artery. Three-dimensional digital subtraction angiography showed two fusiform aneurysms located in the V1 to V2 segments of the left VA (proximal aneurysm: maximum diameter [MaxD] 58 mm, distal aneurysm: MaxD 14 mm) (Fig. 2A). There were no findings suggestive of VA dissection and leakage of the contrast medium (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, a 5-Fr guiding sheath (Shuttle; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was inserted and placed in the V2 segment of the right VA via the right femoral artery. After confirming dominancy of the right VA with retrograde blood supply to the left posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) and the aneurysm of the left V2 segment (Fig. 2C), the aneurysm was trapped. From a 5-Fr guiding catheter delivered to the origin of the left VA, a microcatheter (SL10; Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) was positioned in the proximal aneurysm. Initially, delivering the microcatheter into the distal aneurysm in an antegrade fashion was attempted. The microcatheter could not be guided through the proximal VA aneurysm to the distal VA aneurysm because the outflow zone was not clearly delineated and the bifurcation angle of the distal VA branching from the outflow zone was too acute. In addition, because of large amount of thrombus in the proximal aneurysm, frequent intra-aneurysm manipulation of the microcatheter could cause distal embolism. Therefore, the embolization of the left distal vertebral aneurysm was performed using the contralateral right VA approach. Coils (Target; Stryker) were loosely packed into the proximal aneurysm for scaffolding and back into the vascular lumen proximal to the aneurysm, where the VA was tightly packed to block blood flow (Fig. 2D). A 4.2-Fr distal access catheter (DAC) (Fubuki; Asahi Intecc, Aichi, Japan) was inserted from the 5-Fr guiding sheath placed in the V2 segment of the right VA to the V3 segment of the left VA via the VA union. A microcatheter (SL10) was positioned in the distal aneurysm. Coils (Target) were loosely packed into the aneurysm for scaffolding and back into the vascular lumen distal to the aneurysm, where the VA was tightly embolized with coils to block blood flow (Fig. 2E). Obliteration of the aneurysm was confirmed by bilateral VAG. The day after treatment, the left anterior neck pain disappeared.

Fig. 2. Three-dimensional digital subtraction angiography (A) showing two fusiform aneurysms located in the V1 to V2 segments of the left VA (proximal aneurysm: thrombosis [asterisk] with MaxD 5.8 mm, distal aneurysm: no thrombus with MaxD 14 mm). Left VAG (B) showing no findings of VA dissection and leakage of the contrast medium. Right VAG (C) showing retrograde blood supply to the left PICA and the aneurysm in the left V2 segment beyond the VA union. Bilateral VAG (D and E) showing complete obliteration of the aneurysm. The arrow: the inflow zone of the proximal giant aneurysm, the arrowhead: VA. MaxD: maximum diameter, PICA: posterior inferior cerebellar artery, VA: vertebral artery, VAG: vertebral angiography.

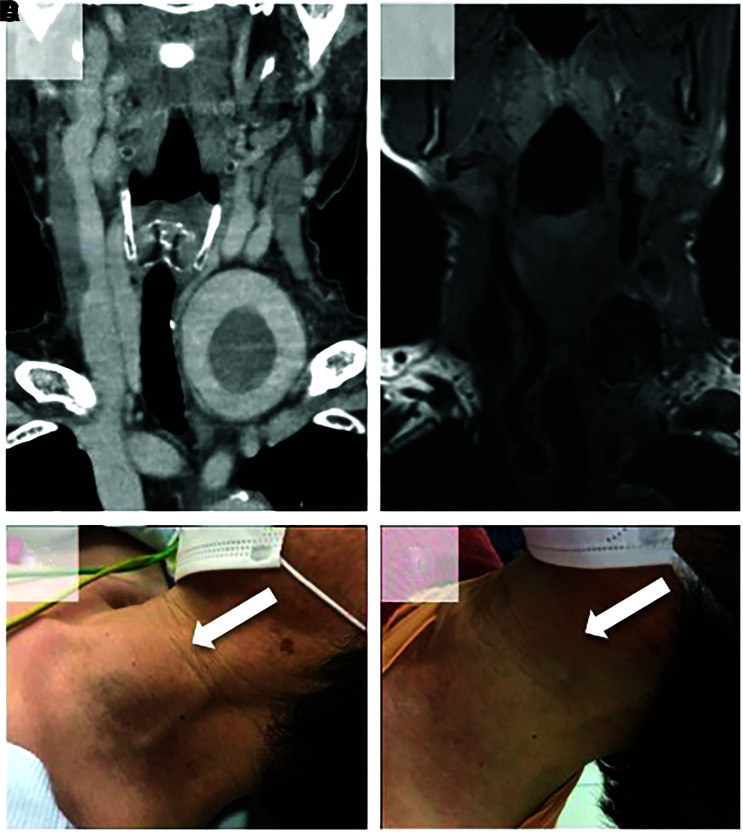

She was discharged 9 days after treatment without neurological deficits. After the operation, the left VAn shrank gradually, without recurrence of pain. One year after the operation, MRI of the neck showed that the size of the aneurysm was 27 × 36 × 27 mm3, which was smaller than before treatment (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Pretreatment (A) coronal CTA and at one year after treatment (B) T1-weighted MRI showing the reduction in aneurysm size. Photographs of the preoperative (C) and postoperative (D) anterior cervical region. Note that subcutaneous swelling has disappeared dramatically one year after treatment (white arrow). CTA: computed tomography angiography, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Discussion

A rare case of a symptomatic thrombotic giant aneurysm located in the V1–V2 segments of the left VA that was successfully treated by endovascular trapping is described. After treatment, improvement of left anterior neck pain and reduction of aneurysm size were observed. She had no relevant medical, traumatic, neck surgery, or family hereditary disease history. Furthermore, infection and vasculitis were also negative because her WBC count and CRP were normal. From the above, the etiology of the aneurysm was considered to be idiopathic. Bone erosion in the transverse foramen of the cervical vertebra suggested that this aneurysm was diagnosed in the chronic stage.

In a literature search to identify all cases of non-traumatic extracranial VAns described in the medical literature,5,8,11–33) PubMed (U.S. National Library of Medicine) was searched using the following terms: “extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm,” “neurofibromatosis type 1,” “Ehlers-Danlos syndrome,” “Marfan's syndrome,” “Behçet’s disease,” “fibromuscular dysplasia,” “connective tissue disorder,” and “collagen disease.” A total of 25 non-traumatic extracranial VAns, including the present case, treated by endovascular surgery have been previously reported (Table 1). Of these, only seven VAns, including three unruptured ANs, underwent endovascular trapping. All of them were located in the V1 and V2 segments. The mean MaxD of the aneurysm was 34.6 mm (range, 15–58 mm). Only the present case had a thrombosed aneurysm. The mean follow-up period was 5.7 months (range, 0–12 months). In all cases, the outcomes after trapping were good recovery, except for one ruptured case. Aneurysmal trapping will be an alternative strategy for symptomatic giant thrombotic VAns in the V1 and V2 segments.

Table 1. Reported cases of endovascular treatment for non-traumatic extracranial VAn, including the present case.

| Case no. | Author (year) | Age (years)/sex | Side | Location (segment) | Size | Thrombosis | Symptoms | Ruptured or unruptured | Endovascular treatment | Follow- up period (mos) | Outcome | Etiology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Detwiler et al. (1987)14) | 52/F | Left | C2 | 70 × 90 mm2 | Yes | Neck mass, neck pain, bruits | Unruptured | PAO (balloon) | 6 weeks | GR | NF-1 |

| 2 | Negoro et al. (1990)15) | 47/M | Left | C1 | NR | NR | Neck pain, cervical hematoma | Ruptured | PAO (balloon) | 5 | GR | NF-1 |

| 3 | Horsley et al. (1997)16) | 56/F | Left | C5–C7 | NR | NR | Neck pain, arm paresthesias, neck mass | Ruptured | Embolization (coil) | 24 | GR | NF-1 |

| 4 | Ushikoshi et al. (1999)17) | 40/F | Left | V3 | NR | NR | Occipitalgia, cervical hematoma | Ruptured | PAO (balloon) | 132 | GR | NF-1 |

| 5 | Dong et al. (2006)18) | 32/M | Left | C3–C4 | 50 × 40 mm2 | Yes | Neck pain, fatigue, numbness of the left arm, pulsatile mass, tenderness, bruit | Unruptured | Covered stent placement | 6 | GR | Behçet’s disease |

| 6 | Hieda et al. (2007)19) | 36/F | Left | Ostium of VA | 49 × 37 mm2 | Yes | Back pain, chest pain, dyspnea, hypotension, hemothorax, coma | Ruptured | Embolization (coil and NBCA) | NR | D | NF-1 |

| 7 | Hiramatsu et al. (2007)20) | 67/M | Left | V1 | 20 × 20 mm2 | NR | Dizziness | Unruptured | Trapping (coil) | 1 week | GR | NF-1 |

| 8 | Pereira et al. (2007)21) | 14/F | Right | C5–C6 | NR | Yes | Radiculopathy | Unruptured | PAO (coil) | 96 | GR | NF-1 |

| 9 | Peyre et al. (2007)22) | 18/F | Right | C5–C6 | 25 mm | No | C6 radiculopathy | Unruptured | PAO (coil) | 72 | GR | NF-1 |

| 10 | Badran et al. (2008)23) | 59/M | Right | V3 | NR | NR | Nonpulsatile peritonsillar swelling | Ruptured | NR | 3 | GR | NR |

| 11 | Horie et al. (2008)24) | 30/F | Right | C6–C7 | NR | Yes | C6 radiculopathy | Unruptured | Embolization (coil and balloon) | 18 | GR | NF-1 |

| 12 | Higa et al. (2010)25) | 60/F | Left | NR | NR | NR | Cervical hematoma, stridor, respiratory failure | Ruptured | Embolization (coil) | 3 | SD (after 3 months, ventilator dependent) | NF-1 |

| 13 | Morvan et al. (2011)26) | 36/F | Left | V3 | 17 × 13 mm2 | NR | Headache, neck pain, vomiting, SAH | Ruptured | Embolization (coil and stent) | 0 | NR | NF-1 |

| 14 | Hiramatsu et al. (2012)8) | 31/M | Right | C6 | NR | NR | Neck pain, cervical hematoma, C6 radiculopathy | Ruptured | Trapping (coil) | 0 | GR | NF-1 |

| 15 | Shang et al. (2013)27) | 26/M | Right | V1 | 40 mm | NR | Right arm and chest pain, arm paresthesias, pulsatile nontender mass in his right supraclavicular region | Unruptured | Trapping (coil and covered stent) | 1 | GR | NR |

| 16 | Ronchey et al. (2014)28) | 54/M | Left | V2 | 28 mm | NR | Neck pain, vertigo, tinnitus, loss of balance | Unruptured | Covered stent placement | 18 | GR | NR |

| 17 | Rao et al. (2015)5) | 26/F | Right | V2 | 12 × 16 × 8 mm3 | Yes | Right neck pain radiating to the right arm, weakness, paresthesias | Unruptured | PAO (coil) | 4 | GR | Behçet’s disease |

| 18 | Kollmann et al. (2016)29) | 48/F | Left | V1 | 11 × 10 mm2 | NR | Massive hematoma of the left neck | Ruptured | Embolization (coil and Onyx) | 12 | GR | NR |

| 19 | Uneda et al. (2016)30) | 35/F | Right | C3–C4 | 15 mm | NR | C3 radiculopathy | Ruptured | Trapping (coil) | 3 | GR | NF-1 |

| 20 | Kiyohira et al. (2017)11) | 59/F | Left | V1 | 42 × 38 × 48 mm3 | Yes | Swelling in the left anterior neck | Unruptured | PAO (coil) | 24 | GR | NR |

| 21 | Strambo et al. (2017)31) | 53/M | Left | V1 | 40 mm | Yes | Dysarthria, right side paresthesias, left limbs ataxia | Unruptured | PAO (coil) | 24 | NR | NF-1 |

| 22 | Maki et al. (2018)32) | 59/NR | Left | C4–C5 | NR | NR | Comatose state, SAH, acute hydrocephalus | Ruptured | Trapping (coil) | 12 | D (because of pneumonitis 1 year after the discharge) | NF-1 |

| 23 | Han et al. (2019)33) | 36/M | Left | C6 | 30–40 mm | NR | Dyspnea, hemothorax | Ruptured | Trapping (coil) | 12 | GR | NF-1 |

| 24 | Plou et al. (2019)12) | 48/F | Left | V2–V3 | 11 × 19 × 20 mm3 | Yes | Pain, cervical rigidity | Ruptured | Flow diverter stent placement | 24 | GR | Idiopathic |

| 25 | Wu et al. (2020)13) | 72/F | Right | V3 | 7.9 × 6.6 mm2 | NR | Occipital headache, vertigo, tinnitus, nausea, pulsatile masses with bruit | Unruptured | Flow diverter stent placement | 12 | GR | NR |

| 26 | Present case | 68/F | Left | V1–V2 | 47 × 58 × 47 mm3 | Yes | Swelling and pain in the left anterior neck | Unruptured | Trapping (coil) | 12 | GR | Idiopathic |

D: death, F: female, GR: good recovery, M: male, NBCA: n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, NF-1: neurofibromatosis type 1, NR: not reported, PAO: parent artery occlusion, SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage, SD: severely disabled, VA: vertebral artery.

The treatment options for symptomatic fusiform VAns included direct surgery and endovascular surgery. As for direct surgery, trapping and ligation were performed under thoracotomy.3,34) When the aneurysm is located in the thoracic cavity, direct surgery is invasive and the complication rate is comparatively high due to surgical insults to the thoracic cavity, including excision of the clavicle, ribs, and sternum.35) Morimoto et al. reported that extracranial VAns were treated by direct surgery in combination with bypass and that one patient developed a cerebral infarction due to delayed occlusion of a saphenous vein graft two months after surgery.36) On the other hand, in recent years, endovascular treatment has been attempted.19,37) The advantage of endovascular treatment is that it is minimally invasive with a smaller wound and involves less blood loss than direct surgery. In addition, the duration of the procedure could be shorter.7,8)

Endovascular treatment for fusiform VAns includes reconstruction technique (stent-graft placement and flow diverter stent placement) and deconstruction technique (proximal occlusion and trapping). If the VA on the aneurysm side does not have ischemic tolerance, reconstruction technique needs to be selected,12,18) because occlusion of the ipsilateral VA leads to an ischemic change of 8% when the blood flow in the contralateral VA is poor.38) In the present case, deconstruction technique was considered to be tolerable because the aneurysm of the V2 segment of the VA and the contralateral PICA were retrogradely supplied by the contralateral VA.

Compared with endovascular trapping, proximal occlusion in the deconstruction technique that embolizes only the parent artery proximal to the aneurysm might be inadequate for long-term therapeutic effects because of collateral circulation surrounding the parent arteries. Strambo et al. reported that proximal occlusion was implemented for vertebrobasilar embolic strokes caused by a primary, partially thrombosed, giant fusiform aneurysm of the left extracranial VA, but six years later, the result was stroke recurrence because the aneurysm had been revascularized from its distal portion by reverse blood flow coming from the patent vertebrobasilar axis.31) Furthermore, following treatment with proximal occlusion with a detachable balloon, a vertebral arteriovenous fistula developed in the same region 11 years later.17) These might be therapeutic pitfalls of proximal occlusion.

Considering these, especially in the case of a thrombosed aneurysm, endovascular trapping (distal and proximal parent artery occlusion) is a more desirable procedure to prevent embolic strokes and the development of vertebral arteriovenous fistula. Endovascular trapping for symptomatic extracranial giant vertebral aneurysms with thrombosis is minimally invasive and may provide good clinical outcome.

The necessity of surgical treatment for unruptured extracranial VAns is controversial, because an accurate estimate of the probability of rupture in the extracranial VAn is not available.27) Rupture of an extracranial VAn can be fatal due to hemorrhagic shock, sudden obstruction of airway occlusion, and intrathoracic hemorrhage.6,7,25) Rupture in the thoracic cavity causes intrathoracic bleeding, which can progress to hypoxic encephalopathy due to acute respiratory insufficiency and has a poor prognosis.8) Griffiths et al. reported that in intrathoracic hemorrhage secondary to vascular abnormalities associated with NF1, of 19 patients, four patients without surgical intervention died and of the remaining 15 patients who underwent thoracotomy, only nine patients survived.39) In addition, Hiramatsu et al. reported that nine patients with ruptured extracranial VAns associated with NF1 underwent treatment, but two patients were in a vegetative state, and two patients died due to the effects of hypoxic encephalopathy.8) Furthermore, of the seven patients with symptomatic unruptured aneurysms, all six who were treated had a good recovery, whereas one patient who was followed up conservatively was severely disabled.8) Rupture of an extracranial VAn can be fatal; therefore, aggressive treatment before the aneurysm ruptures is important. As shown in Table 1, most ruptured extracranial VAns were associated with NF-1, suggesting that aggressive treatment might be required prior to rupture.

Endovascular trapping will be an alternative strategy for a symptomatic giant thrombotic aneurysm of the V1 and V2 segments of the VA if the patient can tolerate ischemia. However, trapping with a coil inserted in the aneurysm could cause a coil mass effect. Coil placement in the aneurysm should be kept to a minimum. In addition, the long-term outcome of endovascular trapping is still unknown. A thrombosed giant aneurysm has the potential risk of growth from the vasa vasorum.40,41) Iihara et al. reported that trapping of the parent artery with coils for a partially thrombosed giant aneurysm of the intracranial VA, even if there was no angiographically demonstrated evidence of filling, cannot suppress aneurysm enlargement from the vasa vasorum.40) In the future, the long-term prognosis also needs to be investigated.

Conclusion

Endovascular trapping will be an alternative strategy for a symptomatic giant thrombotic aneurysm of the V1 and V2 segments of the VA if the patient can tolerate ischemia.

Footnotes

Informed Consent

The authors obtained informed consent from the patient and her family.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1). Foreman PM, Griessenauer CJ, Falola M, Harrigan MR: Extracranial traumatic aneurysms due to blunt cerebrovascular injury. J Neurosurg 120: 1437– 1445, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Morasch MD, Phade SV, Naughton P, Garcia-Toca M, Escobar G, Berguer R: Primary extracranial vertebral artery aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg 27: 418– 423, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Sumimura J, Nakao K, Miyata M, Kamiike W, Yokota H, Kawashima Y: Vertebral aneurysm of the neck. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 29: 63– 65, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Park SH, Yim MB, Lee CY, Kim E, Son EI: Intracranial fusiform aneurysms: it’s pathogenesis, clinical characteristics and managements. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 44: 116– 123, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Rao S, Rao S, Dhindsa-Castanedo L, Benndorf G: Rapidly evolving large extracranial vertebral artery pseudoaneurysm in Behçet’s disease: case report and review of the literature. Mod Rheumatol 25: 476– 479, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Miyazaki T, Ohta F, Daisu M, Hoshii Y: Extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm ruptured into the thoracic cavity with neurofibromatosis type 1: case report. Neurosurgery 54: 1517– 1520; discussion 1520–1511, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Arai K, Sanada J, Kurozumi A, Watanabe T, Matsui O: Spontaneous hemothorax in neurofibromatosis treated with percutaneous embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 30: 477– 479, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Hiramatsu H, Matsui S, Yamashita S, et al. : Ruptured extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 52: 446– 449, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Kao CL, Tsai KT, Chang JP: Large extracranial vertebral aneurysm with absent contralateral vertebral artery. Tex Heart Inst J 30: 134– 136, 2003 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Sultan S, Morasch M, Colgan MP, Madhavan P, Moore D, Shanik G: Operative and endovascular management of extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a clinical dilemma--case report and literature review. Vasc Endovascular Surg 36: 389– 392, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Kiyohira M, Ishihara H, Oku T, Kawano A, Oka F, Suzuki M: Successful endovascular treatment for thrombosed giant aneurysm of the V1 segment of the vertebral artery: a case report. Interv Neuroradiol 23: 628– 631, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Plou P, Landriel F, Beltrame S, et al. : Flow diverter for the treatment of pseudoaneurysms of the extracraneal vertebral artery: report of two cases and review of the literature. World Neurosurg 127: 72– 78, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Wu H, Wang M, Li K, Wang F: Treatment of extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm with flow diversion. World Neurosurg 138: 328– 331, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Detwiler K, Godersky JC, Gentry L: Pseudoaneurysm of the extracranial vertebral artery. Case report. J Neurosurg 67: 935– 939, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Negoro M, Nakaya T, Terashima K, Sugita K: Extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm with neurofibromatosis. Endovascular treatment by detachable balloon. Neuroradiology 31: 533– 536, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Horsley M, Taylor TK, Sorby WA: Traction-induced rupture of an extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm associated with neurofibromatosis. A case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 22: 225– 227, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Ushikoshi S, Goto K, Uda K, Ogata N, Takeno Y: Vertebral arteriovenous fistula that developed in the same place as a previous ruptured aneurysm: a case report. Surg Neurol 51: 168– 173, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Dong ZH, Fu WG, Guo DQ, et al. : Endovascular repair for a huge vertebral artery pseudoaneurysm caused by Behcet’s disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 119: 435– 437, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Hieda M, Toyota N, Kakizawa H, et al. : Endovascular therapy for massive haemothorax caused by ruptured extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm with neurofibromatosis type 1. Br J Radiol 80: e81– 84, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Hiramatsu H, Negoro M, Hayakawa M, et al. : Extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. A case report. Interv Neuroradiol 13: 90– 93, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Pereira VM, Geiprasert S, Krings T, et al. : Extracranial vertebral artery involvement in neurofibromatosis type I. Report of four cases and literature review. Interv Neuroradiol 13: 315– 328, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Peyre M, Ozanne A, Bhangoo R, et al. : Pseudotumoral presentation of a cervical extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm in neurofibromatosis type 1: case report. Neurosurgery 61: E658; discussion E658, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Badran K, Mani N, Axon P: Spontaneous parapharyngeal haematoma caused by a leaking vertebral artery pseudoaneurysm. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 265: 251– 254, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Horie N, Morikawa M, Kitagawa N, Nakamoto M, Nagata I: Successful endovascular occlusion of an aneurysm of the cervical vertebral artery associated with neurofibromatosis-1. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 150: 847– 848, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Higa G, Pacanowski JP, Jr., Jeck DT, Goshima KR, León LR, Jr.: Vertebral artery aneurysms and cervical arteriovenous fistulae in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Vascular 18: 166– 177, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Morvan T, de Broucker F, de Broucker T: Subarachnoid hemorrhage in neurofibromatosis type 1: case report of extracranial cerebral aneurysm rupture into a meningocele. J Neuroradiol 38: 125– 128, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Shang EK, Fairman RM, Foley PJ, Jackson BM: Endovascular treatment of a symptomatic extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 58: 1391– 1393, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Ronchey S, Serrao E, Kasemi H, Fazzini S, Mangialardi N: Endovascular treatment of extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm and aberrant right subclavian artery aneurysm. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 55: 265– 269, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Kollmann D, Kinstner C, Teleky K, et al. : Successful treatment of a ruptured extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm with onyx instillation. Ann Vasc Surg 36: 290.e297– 290.e210, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Uneda A, Suzuki K, Okubo S, Hirashita K, Yunoki M, Yoshino K: Neurofibromatosis type 1-associated extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm complicated by vertebral arteriovenous fistula after rupture: case report and literature review. World Neurosurg 96: 609.e613– 609.e618, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Strambo D, Peruzzotti-Jametti L, Semerano A, et al. : Treatment challenges of a primary vertebral artery aneurysm causing recurrent ischemic strokes. Case Rep Neurol Med 2017: 2571630, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Maki Y, Ishibashi R, Fukuda H, Kobayashi M, Chin M, Yamagata S: Subarachnoid hemorrhage from vertebral arteriovenous fistula without perimedullary drainage: rare stroke hemorrhagic event in a patient of neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 58: 185– 188, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Han KS, Lee KM, Kim BJ, Kwun BD, Choi SK, Lee SH: Life-threatening hemothorax caused by spontaneous extracranial vertebral aneurysm rupture in neurofibromatosis type 1. World Neurosurg 130: 157– 159, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Nenadic D, Balevic M, Milojevic M, Tanskovic S: Extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm rupture complicated by extrapleural haematoma. EJVES Short Rep 38: 12– 14, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Coselli JS, Crawford ES: Surgical treatment of aneurysms of the intrathoracic segment of the subclavian artery. Chest 91: 704– 708, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Morimoto K, Matsuda H, Fukuda T, et al. : Hybrid repair of proximal subclavian artery aneurysm. Ann Vasc Dis 8: 87– 92, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Amaral JF, Grigoriev VE, Dorfman GS, Carney WI, Jr.: Vertebral artery pseudoaneurysm. A rare complication of subclavian artery catheterization. Arch Surg 125: 546– 547, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Blickenstaff KL, Weaver FA, Yellin AE, Stain SC, Finck E: Trends in the management of traumatic vertebral artery injuries. Am J Surg 158: 101– 105; discussion 105–106, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Griffiths AP, White J, Dawson A: Spontaneous haemothorax: a cause of sudden death in von Recklinghausen’s disease. Postgrad Med J 74: 679– 681, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40). Iihara K, Murao K, Sakai N, et al. : Continued growth of and increased symptoms from a thrombosed giant aneurysm of the vertebral artery after complete endovascular occlusion and trapping: the role of vasa vasorum. Case report. J Neurosurg 98: 407– 413, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41). Pahl FH, Vellutini Ede A, Cardoso AC, de Oliveira MF: Vasa vasorum and the growing of thrombosed giant aneurysm of the vertebral artery: a case report. World Neurosurg 85: 368.e361– 364, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]