ABSTRACT

Since 2015, the United States has experienced a resurgence in the number of mumps cases and outbreaks in fully vaccinated populations. These outbreaks have occurred predominantly in close-quarter settings, such as camps, colleges, and detention centers. Phylogenetic analysis of 758 mumps-positive samples from outbreaks across the United States identified 743 (98%) as genotype G based on sequence analysis of the mumps small hydrophobic (SH) gene. Additionally, SH sequences in the genotype G samples showed almost no sequence diversity, with 675 (91%) of them having identical sequences or only one nucleotide difference. This uniformity of circulating genotype and strain created complications for epidemiologic investigations and necessitated the development of a system for rapidly generating mumps whole-genome sequences for more detailed analysis. In this study, we report a novel and streamlined assay for whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of mumps virus genotype G. The WGS procedure successfully generated 318 high-quality WGS sequences on nucleic acid from genotype G-positive respiratory samples collected during several mumps outbreaks in the United States between 2016 and 2019. Sequencing was performed by a rapid and highly sensitive custom Ion AmpliSeq mumps genotype G panel, with sample preparation performed on an Ion Chef and sequencing on an Ion S5. The WGS data generated by the AmpliSeq panel provided enhanced genomic resolution for epidemiological outbreak investigations. Translation and protein sequence analysis also identified several potentially important epitope changes in the circulating mumps genotype G strains compared to the Jeryl-Lynn strain (JL5) used in vaccines in the United States, which could explain the current level of vaccine escapes.

KEYWORDS: AmpliSeq, genotyping, mumps, vaccine, whole-genome sequencing, molecular epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Mumps is a highly contagious, vaccine-preventable viral disease characterized by fever, malaise, and parotitis. Although not usually life-threatening, serious complications can occur, including pancreatitis, orchitis, mastitis, and meningoencephalitis, which can result in severe neurological sequelae, including deafness and sterility in males (1, 2). Mumps virus is a member of the genus Rubulavirus in the family Paramyxoviridae. The mumps virus is delineated into 12 distinct genotypes, A to N (excluding E and M), based on nucleotide differences in the gene coding for the small hydrophobic (SH) protein (3, 4). In the prevaccine era, the incidence of mumps in the United States was greater than 100 cases per 100,000 population annually (5). After the advent of the two-dose measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR), the incidence decreased to 0.1 cases per 100,000 population by 2001 (6). The relative success of the MMR program and consequent low case counts led to the establishment of a national health objective to eliminate indigenous mumps transmission by 2010 (7). However, in recent years, mumps has reemerged in the United States despite widespread vaccine coverage. The largest U.S. mumps epidemic in approximately 20 years occurred in 2006 when the incidence rose to 2.2 cases per 100,000 population. Of the cases with known vaccine status, the majority (63%) had previously received the recommended two doses (8). Between 2015 and 2019, numerous mumps outbreaks were reported across the United States, and most of the mumps viruses in those outbreaks were identified as genotype G. These findings have raised questions about the effectiveness of the current vaccine, which is genotype A (9, 10).

The increase in mumps outbreaks has also resulted in a spike in the number and scope of epidemiological investigations, which have been hampered by the prevalence of genotype G as the causative strain and the poor resolution of the currently established mumps genotyping method. Although the SH gene is the most variable in the mumps genome, with nucleotide heterogeneity of only 20% between genotypes (4), identical SH gene sequences have been found in recent outbreaks (11). Even between distinct outbreaks, few single-nucleotide polymorphisms (0 to 5) differentiate the genotype G strains. In fact, one recent study found that among all mumps samples genotyped between 2015 and 2017, 98.7% were genotype G, with two strains accounting for 78.3% of them (12). This lack of heterogeneity has made outbreak tracing and strain differentiation based on the mumps SH gene impossible due to the extremely limited resolution. As a result, recent efforts have been made to combine the mumps fusion (F), hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN), and SH gene sequences to provide meaningful epidemiological information (11, 13). However, this requires sequencing three independent gene regions of the virus genome with conventional methods that are often laborious and time-consuming (11, 13). They also often suffer from poor sensitivity, necessitating the use of viral isolates or nested PCR to obtain good-quality sequences (11). High-resolution data from mumps WGS have also been shown to generate data that facilitate the estimation of transmission links between individual cases, which can be highly beneficial for infection control efforts (14). The methods currently employed for mumps WGS, however, are also quite laborious and are dependent on viral isolates (14, 15). Therefore, we sought to generate a streamlined and highly sensitive assay for WGS of mumps genotype G that could be applied directly to positive clinical specimens for maximum speed of strain resolution and molecular epidemiological tracking.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample selection.

Urine, buccal swabs, and other respiratory swabs in viral transport medium were received from New York State patients with suspected mumps disease between 2013 and 2019. A total of 801 samples were identified as mumps-positive with a real-time reverse transcription-PCR (rRT-PCR) assay developed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that targets the nucleocapsid protein (NP) gene (16). Of those, 758 samples were successfully genotyped with a CDC-designed RT-PCR and sequencing assay targeting the entire SH gene (3). Of the samples successfully genotyped, 743 where genotype G and 318 were selected for WGS in this study.

Molecular methods.

Nucleic acid extraction was performed with the NucliSENS easyMAG instrument (bioMérieux, Durham, NC) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions using the generic 2.0.1 protocol. cDNA was generated with the Superscript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA was then amplified using the mumps genotype G AmpliSeq panel, consisting of approximately 1,200 primers divided into two pools. The panel amplifies nearly the entire genome with 628 overlapping amplicons, each of which is approximately 200 bp. Automated emulsion PCR, cleanup, library preparation, and chip loading were performed using an Ion 520 kit onboard the Ion Chef instrument (ThermoFisher, Pleasanton, CA) and sequencing was performed on the Ion S5XL (ThermoFisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequence analysis.

Using Geneious R11, sequences were trimmed, normalized, and error corrected (minimum depth, 6; mark uncorrectable) and mapped to reference GenBank accession no. KY969482. The 50% consensus sequence was extracted, aligned to the reference sequence using MAFFT compared to the original mapped sequence, and manually corrected (frameshift insertions and deletions were corrected).

Genotype G sequences were aligned using MAFFT in Geneious R11, and phylogenetic trees were constructed in MEGA X. Comparisons of the F, SH, and HN gene sequences were performed by concatenation of the individual gene sequences generated by the WGS data.

Additional sequence analyses were performed to design appropriate modifications to the mumps NP gene target rRT-PCR assay. The sequence alignments for the revised mumps rRT-PCR assay were based on a mumps NP gene consensus sequence derived from AmpliSeq sequences from 318 positive New York State specimens and a selection of mumps genotypes obtained from GenBank. The latter included genotype G sequences from 2001 to 2017 and additional genotypes A, C, K, F, H, I, and N from outbreaks around the world.

Molecular epitope modeling.

The corresponding protein structures from the HN gene sequences of several mumps samples from this study and those of the U.S. vaccine strain Jeryl Lynn 5 (JL5) were compared using PyMOL version v7.0. Structural modeling was performed using the PyMOL 1.8.2.3 software, and mumps HN protein entry 5B2D at rcsb.org was used as a template (17).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Between 2013 and 2019, 758 primary clinical samples collected in New York State were positively identified as mumps with the CDC mumps-specific rRT-PCR assay. Genotype G was identified in 98% (743/758) of the samples with limited diversity based on phylogenetic analysis of the SH gene sequences. Almost half, 48.9% (371/758), of the genotype G SH gene sequences were identical to the reference strain, MuVi/Sheffield.GBR/1.05/, with another 40% (303/758) identical to a sequence with just one nucleotide substitution, Sheffield-C248 T (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of the relative abundances of four types of mump genome sequences by year

| Year | Distribution [% (no./total no.)] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheffielda | Sheffield C248T | Other G | Other genotypes | |

| 2013 | 0 (0/15) | 60 (9/15) | 40 (6/15) | |

| 2014 | 56 (14/25) | 4 (1/25) | 36 (9/25) | 4 (1/25) |

| 2015 | 79 (26/33) | 6 (2/33) | 6 (2/33) | 9 (3/33) |

| 2016 | 31 (66/214) | 60.1 (129/214) | 8.4 (18/214) | 0.5 (1/214) |

| 2017 | 48.6 (126/259) | 43.6 (113/259) | 5.8 (15/259) | 2 (5/259) |

| 2018 | 73 (79/109) | 17 (19/109) | 8.2 (9/109) | 1.8 (2/109) |

| 2019 | 58 (60/103) | 29 (30/103) | 10 (10/103) | 3 (3/103) |

| Total | 48.9 (371/758) | 40.0 (303/758) | 9.1 (69/758) | 2.0 (15/758) |

The mumps reference strain MuVi/Sheffield.GBR/1.05/, referred to as Sheffield, and a sequence with one nucleotide substitution (C248T) compared to Sheffield, referred to as Sheffield-C248T, are identical to the majority of genotype G sequences observed in New York State from 2013 to 2019.

The lack of heterogeneity hampers epidemiological investigations and prompted us to develop a method for generating mumps genotype G WGS. Of the 743 genotype G samples, 318 were selected for WGS based on threshold cycle (CT) values and significance for outbreak tracing. Of those 318 samples, all produced near-whole-genome sequences, with the exception of small regions at the 5′ (84 nucleotides) and 3′ (76 nucleotides) untranslated regions (UTRs) that did not sequence due to lack of primer coverage. The genotype G AmpliSeq panel achieved a coverage of 99%, minimum depth of 20×, maximum depth of 10,000×, and average depth of 1,014×. The approximate limit of detection (LOD) for the assay was determined to be equivalent to a CT of approximately 34 or 20 gene copies per reaction for specimens tested with the CDC mumps rRT-PCR assay (data not shown). The assay successfully generated 99% coverage of the mumps genome 100% of the time as long as the sample had a CT value of 34 on the CDC’s mumps rRT-PCR assay.

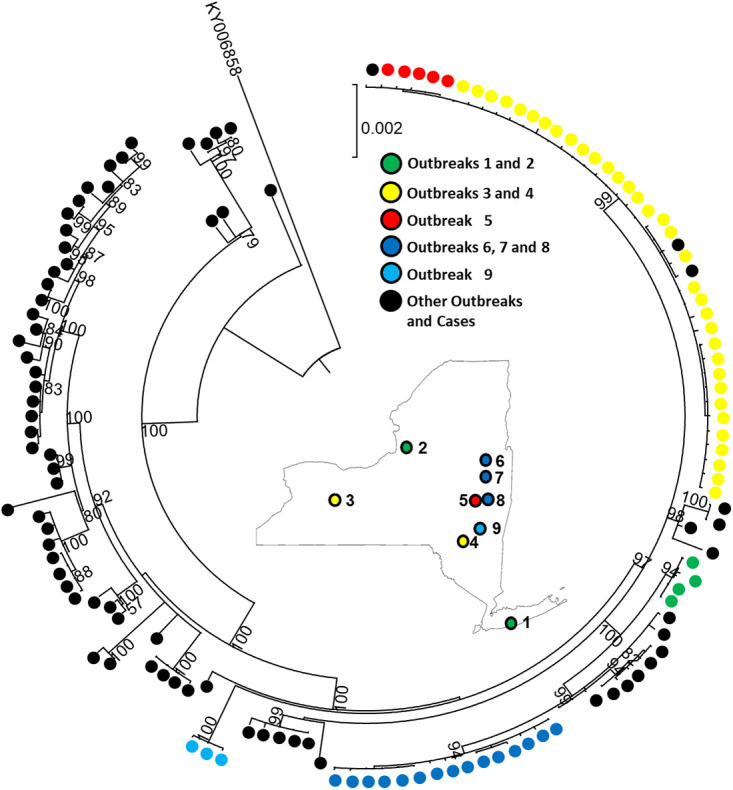

It has been suggested that accurate mumps outbreak tracing requires a minimum of the F, SH, and HN gene sequences (11). However, given the significant homogeneity of sequences between closely related outbreaks, the enhanced sequence resolution provided by WGS is likely crucial for outbreak tracing. To test this theory, 63 of the high-quality WGS sequences from specific outbreaks across New York State were chosen based on epidemiological interest and relatedness to generate three corresponding maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees. The first tree contained only the SH gene sequences (Fig. 1A), the second was generated with concatenated sequences from the SH, F, and HN gene sequences (Fig. 1B), and the third was generated from the mumps genome sequence (Fig. 1C). Importantly, while the three-gene approach was able to accurately differentiate most outbreaks, such as outbreak four (orange sequences Fig. 1), only the WGS approach was able to differentiate more closely related outbreaks, such as outbreaks one and two (blue and gray sequences, respectively, in Fig. 1). The three-gene approach also failed to accurately group other samples associated with specific outbreaks, such as outbreak five (red sequences, Fig. 1), which were delineated with the WGS approach (Fig. 1). While there was epidemiological suspicion that certain outbreaks were linked, the molecular information proved invaluable for confirming those suspicions. The outbreaks discussed were across a wide range of geographic locations in New York State, but all were from college campuses or within college or professional sports teams. Additional samples were selected for the WGS approach based on further epidemiological information in an effort to link geographically distant outbreaks including outbreaks one and two (green), three and four (yellow), and six, seven, and eight (blue) (Fig. 2). The WGS data were able to confirm the epidemiological suspicion that samples from these outbreaks were linked despite being geographically distant. It is important to note, however, that it was the existing epidemiological information concerning certain outbreaks that steered the interest and phylogenetic analysis that resulted in the concrete linking of specific outbreaks. This marriage of epidemiological information with highly resolved phylogenetic analysis makes the determination of outbreak relatedness possible and informative. Further samples from across the United States were also included in the analysis and identified specific outbreaks in those regions. In agreement with Wohl et al., phylogenetic analysis of most of the mumps samples collected in New York State and other regions of the United States belong to a single lineage within genotype G descending from a mumps outbreak in Iowa in 2006 (14).

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic comparison of sequences from 63 mumps viruses from several outbreaks that occurred in New York State from 2016 to 2017. Samples from individual outbreaks are identified by specific colors, as indicated by the outbreak key. Sequence alignments were generated using the SH gene of the mumps genome (A), concatenated sequences of the SH, F, and HN genes (B), or the mumps whole-genome sequence (C). The evolutionary history was inferred by using the maximum likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model. The phylogeny was tested using 1,000 bootstrap replicates; values of >75 are indicated on the tree. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X.

FIG 2.

Mumps virus genotype G phylogenetic analysis with WGS. Maximum likelihood tree was constructed based on a nucleotide alignment of representative strains from five New York State outbreaks (color coded above). A map of New York State is included with the locations of the selected unique and related outbreaks. Additional individual samples and outbreak samples from across the United States are represented by black dots. Phylogenetic analysis was performed with MEGA X. Only bootstrap values of >50% are displayed.

The WGS data were also used to perform sequence alignments on the oligonucleotides in the CDC mumps rRT-PCR assay which target a portion of the NP gene (18). Alignments included a mumps consensus sequence generated from the 318 AmpliSeq reactions, additional sequences obtained from GenBank, including genotypes A, C, K, F, H, I, and N, and several genotype G strains involved in other outbreaks around the world. A mismatch was identified in the forward primer MuN-687F and two mismatches near the 5′ end of the probe MuN-622P. Therefore, a new forward primer and probe were designed for the CDC mumps real-time assay with the degeneracies as indicated in bold type: MuN-687F (5′-GTATGACAGCDTACGACCAACCT-3′) and MuN-622P (5′-CYGGRTCTGCTGATCGGCGAT-BHQ-3′) (see Fig. 3 for details on the relevant alignments). Interestingly, two genotype G sequences from New Zealand contained one additional change in the probe portion of the mumps rRT-PCR assay that was not seen in the U.S. samples (19). This finding supports the additional utility of WGS as a tool to monitor changes in genomic regions that are critical for mumps detection assays and provides important information about the emergence of new strains with the potential to affect assay detection efficiency and sensitivity.

FIG 3.

Sequence alignment of the modified CDC mumps real-time RT-PCR assay in the NP gene of the consensus sequence of the 318 WGS genotype G genomes and additional genotypes A, C, G, H, I, J, and N. The modified CDC forward primer (MuN-687F) and probe (MuN-622P) are at the top of the alignment. Primer and probe degeneracy modifications in relation to the NP gene target consensus sequence are indicated above yellow boxes and boldfaced in gray. A third mutation located in the probe region of two samples from a 2017 outbreak in New Zealand that was not observed in the 318 WGS samples is indicated by an asterisk.

Mumps surveillance in New York State has identified sporadic cases across all age groups; however, outbreaks during the study period occurred primarily in college-aged individuals (Fig. 4). This was not surprising, as many of the mumps outbreaks occurred at universities. Of more concern was the fact that most of these individuals (61%) had received the recommended 2 doses of mumps vaccine (Fig. 5). This raised the question of whether waning immunity or vaccine escape was the major reason for infections in this largely vaccinated population. To investigate the possibility of vaccine escape, the 318 WGS sequences, including 272 of the New York State mumps samples collected between 2013 and 2019, were compared to JL5 at key B-cell and T-cell immunologically reactive sites in the HN gene. Four amino acid changes were consistently observed (I279T, I287V, L336S, and E356D) and modeled in PyMOL to investigate potential structural changes (Fig. 6). All four mutations resulted in the replacement of larger amino acids with smaller ones, creating significant structural changes in addition to alterations in hydrophobicity and/or hydrogen bonding. The sequence changes are consistent with those reported for mumps genotype G samples identified from other mumps outbreaks across the globe (19, 20).

FIG 4.

Density plot of age distribution for sporadic and outbreak-associated mumps cases. Data represent New York State, excluding New York City. Confirmed and probable cases were reported between 1 January 2016 and 1 June 2017. An outbreak is defined as three or more positive PCR results from a specific location, such as a university, county, or prison.

FIG 5.

Donut chart of MMR status by percentage among reported mumps cases in New York State from January 2016 and June 2017.

FIG 6.

In silico crystal structures modeling the epitope changes in the HN protein of the U.S. vaccine strain Jeryl Lynn 5 (A) compared to a representative genotype G sample (B) from 318 WGS samples. Blue arrows indicate potentially significant amino acid substitutions that were observed in four immunologically reactive regions labeled with their amino acid ranges and represented in magenta. The regions in yellow and white indicate the amino acids with alterations between Jeryl Lynn and the representative genotype G samples, pictured as stick models (A and B) or as spheres (C and D). Magnifications of the potentially significant Leu336Ser and Glu356Asp substitutions between Jeryl Lynn 5 (E) and the representative genotype G (F) epitope regions are represented in magenta, and sphere structures of amino acids are shown in white and yellow with amino acids adjacent to the changes in green. Structural modeling was performed using PyMOL 1.8.2.3, and mumps HN protein 5B2D at rcsb.org was used as a template (17).

Despite being a vaccine-preventable disease, mumps has begun to reemerge, even in populations with high vaccination rates (9). This reemergence has placed a significant burden on the health care system, including laboratory testing capacity, patient care and management, and epidemiological investigations. While previous genotyping methods provided insufficient power to distinguish current outbreak lineages, the mumps genotype G AmpliSeq panel provides a rapid and sensitive method for WGS, with applications including detailed outbreak investigations, molecular epidemiology, monitoring sequence changes for detection assay design, and protein modeling for immunological epitope comparison studies.

Compared to the current conventional genotyping method, which is unable to differentiate genotype G outbreaks, phylogenetic trees generated with WGS provided superior resolution of outbreak relatedness and differentiated outbreaks. Importantly, our data also indicate that WGS of genotype G is the only method capable of accurately tracing all genotype G outbreaks that occurred in New York State from 2016 to 2019. While analysis of the combined sequences of the F, SH, and HN genes was sufficient to differentiate most outbreaks, sequencing three independent gene targets by conventional sequencing is more laborious and requires higher yields of nucleic acid than the AmpliSeq WGS method. Additionally, the F, SH, and HN phylogenetic trees provided more limited resolution than the WGS trees.

There is evidence for both waning immunity and antigenic drift as contributing factors for the recent mumps outbreaks in vaccinated populations. Numerous studies provide evidence of waning mumps immunity over time (21–23). Other studies have also shown a decrease in mumps IgG titer over time and a higher likelihood of mumps infection as time from last vaccination increases (24–26). It should be noted that loss of detectable antibody does not necessarily indicate loss of immunological memory and the ability to generate a protective response if challenged. However, the increased likelihood of mumps infection with time after vaccination is suggestive of loss of protection.

Other studies have identified differences between the U.S. vaccine strain JL5 and the currently circulating genotype G viruses, particularly in the HN gene (14, 20, 27). The HN gene contains the coding information for B-cell and T-cell epitopes, and a recent study identified a lower frequency of mumps-specific memory B cells in college-aged adults (28). Some changes seen, including L336S and I287V, which are known B-cell and T-cell epitopes, respectively, may affect the HN protein and antibody binding. The L336S amino acid change in genotype G compared to JL5 has the potential to strengthen the HN protein via the formation of additional hydrogen bonds with the surrounding amino acids, which are sterically hindered by the leucine in that position in JL5. These potential effects must be tested in vivo but may help to explain the reduced antibody neutralization titers seen in mumps genotype G samples from individuals vaccinated with JL5 (29). Interestingly, a study in 2014 identified I279T and I287V as potentially associated with escape mutations (26). In this study, predicted major histocompatibility complex peptide binding sites and cathepsin cleavage sites were mapped in JL5 and Iowa-06. In contrast to JL5, the predicted high-affinity HLA-DR binding site from codons 275 to 279 is no longer present due to the alteration of a hydrophobic leucine to a hydrophilic threonine in I279T in Iowa-06. A difference between cathepsin B cleavage probability between JL5 and Iowa-06 in the 265 to 295 region as a result of the I279T and I287V substitutions was also identified. The authors hypothesize that these changes result in the loss of a key T-helper epitope, which may prevent induction of T-helper cells necessary for B-cell stimulation. As noted by Dilcher et al., it is possible that the genetic drift in genotype G viruses is contributing to the global increase in mumps outbreaks that began around 2015 (19). It is unlikely a coincidence that the exact amino acid substitutions that were originally observed in the Iowa 2006 outbreak are identical to the substitutions observed not only in this study but also in samples collected from outbreaks around the world. While the significance of these amino acid substitutions would have to be confirmed empirically, their occurrence in such geographically distinct regions of the world seems more than coincidental. Collectively, these findings indicate that a vaccine comprised of a genotype G virus provides better mumps immunity and demonstrates the utility of the mumps AmpliSeq assay for continued surveillance of these substitutions and potentially new substitutions, as is currently done for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The WGS of genotype G samples in this study also identified mismatches with oligonucleotides in the current CDC mumps rRT-PCR detection assay. These mismatches were also observed in samples analyzed by Dilcher et al. from a mumps outbreak in New Zealand (19). However, in that study a third mismatch was identified in the probe region that was never observed in our samples, underscoring the importance of performing sequence analysis for assay modification on samples collected in specific regions of the world where it is being used.

The genotype G AmpliSeq panel provides a method for near-whole-genome sequencing of genotype G samples directly on specimens, with minimal hands-on time and excellent sensitivity. The AmpliSeq technology inherently lacks sequence coverage at the 5′ and 3′ termini of the genome. While this prevents the generation of fully complete genomes, the level of genomic completeness obtained does provide resolution capable of successfully resolving closely related outbreaks, real-time detection assay design, and epitope investigation. Given the inherent difficulties with replacing the current mumps vaccine with a more effective one, including cost, resources, clinical trials, and licensure, it is likely that, at best, policy changes such as the addition of a third MMR dose during outbreaks will be the most practical approach to stemming the number and scope of future mumps outbreaks (30). These obstacles, coupled with declining rates of MMR vaccinations due to the antivaccination efforts by some community groups and, more recently, the disruption of vaccination programs by the COVID-19 pandemic, the likelihood of further mumps outbreaks in the United States and other nations is greatly increased. As a result, mumps WGS assays will become increasingly important and useful tools during response efforts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Applied Genomics Technology Core at the Wadsworth Center for their help in performing dideoxy sequencing and Erica Lasek-Nesselquist for her assistance with annotation and uploading of the mumps whole-genome sequences to GenBank. We also thank the Bureau of Immunization at the NYSDOH for providing epidemiological information, Janice Pata (Wadsworth Center, NYSDOH, and the Department of Biomedical Science at the University at Albany) for her assistance and expertise in utilizing PyMOL, and Sara Griesemer and Amruta Moghe for technical assistance. We also thank the Hawaii DOH and the Indiana DOH for generously providing primary mumps samples for WGS.

This work was supported in part by Cooperative Agreement Number NU60OE000104, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Association of Public Health Laboratories. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

P.B., H.C., D.L., and T.Y. declare no competing interests. K.S.G. receives research support from ThermoFisher for the evaluation of new assays for the detection and characterization of viruses. She also has a royalty-generating collaborative agreement with Zeptometrix.

Contributor Information

Patrick Bryant, Email: Patrick.Bryant@health.ny.gov.

Yi-Wei Tang, Cepheid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hviid A, Rubin S, Muhlemann K. 2008. Mumps. Lancet 371:932–944. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zamir CS, Schroeder H, Shoob H, Abramson N, Zentner G. 2015. Characteristics of a large mumps outbreak: clinical severity, complications and association with vaccination status of mumps outbreak cases. Hum Vaccin Immunother 11:1413–1417. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1021522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin L, Rima B, Brown D, Orvell C, Tecle T, Afzal M, Uchida K, Nakayama T, Song JW, Kang C, Rota PA, Xu W, Featherstone D. 2005. Proposal for genetic characterisation of wild-type mumps strains: preliminary standardisation of the nomenclature. Arch Virol 150:1903–1909. 10.1007/s00705-005-0563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin L, Orvell C, Myers R, Rota PA, Nakayama T, Forcic D, Hiebert J, Brown KE. 2015. Genomic diversity of mumps virus and global distribution of the 12 genotypes. Rev Med Virol 25:85–101. 10.1002/rmv.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1978. Mumps surveillance-United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 40:379–381. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNabb SJN, Jajosky RA, Hall-Baker PA, Adams DA, Sharp P, Anderson WJ, Javier AJ, Jones GJ, Nitschke DA, Worshams CA, Richard RA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2007. Summary of notifiable diseases-United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 54:1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. 2000. Healthy people 2010: objectives for improving health. CDC, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLean HQ, Fiebelkorn AP, Temte JL, Wallace GS, CDC. 2013. Prevention of measles, rubella, congenital rubella syndrome, and mumps, 2013: summary recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 62:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayan GH, Quinlisk MP, Parker AA, Barskey AE, Harris ML, Schwartz JM, Hunt K, Finley CG, Leschinsky DP, O'Keefe AL, Clayton J, Kightlinger LK, Dietle EG, Berg J, Kenyon CL, Goldstein ST, Stokley SK, Redd SB, Rota PA, Rota J, Bi D, Roush SW, Bridges CB, Santibanez TA, Parashar U, Bellini WJ, Seward JF. 2008. Recent resurgence of mumps in the United States. N Engl J Med 358:1580–1589. 10.1056/NEJMoa0706589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dayan GH, Rubin S. 2008. Mumps outbreaks in vaccinated populations: are available mumps vaccines effective enough to prevent outbreaks? Clin Infect Dis 47:1458–1467. 10.1086/591196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gouma S, Cremer J, Parkkali S, Veldhuijzen I, van Binnendijk RS, Koopmans MPG. 2016. Mumps virus F gene and HN gene sequencing as a molecular tool to study mumps virus transmission. Infect Genet Evol 45:145–150. 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNall RJ, Wharton AK, Anderson R, Clemmons N, Lopareva EN, Gonzalez C, Espinosa A, Probert WS, Hacker JK, Liu G, Garfin J, Strain AK, Boxrud D, Bryant PW, George KS, Davis T, Griesser RH, Shult P, Bankamp B, Hickman CJ, Wroblewski K, Rota PA. 2020. Genetic characterization of mumps viruses associated with the resurgence of mumps in the United States: 2015–2017. Virus Res 281:197935. 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.197935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui A, Rivailler P, Zhu Z, Deng X, Hu Y, Wang Y, Li F, Sun Z, He J, Si Y, Tian X, Zhou S, Lei Y, Zheng H, Rota PA, Xu W. 2017. Evolutionary analysis of mumps viruses of genotype F collected in mainland China in 2001–2015. Sci Rep 7:17144. 10.1038/s41598-017-17474-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wohl S, Metsky HC, Schaffner SF, Piantadosi A, Burns M, Lewnard JA, Chak B, Krasilnikova LA, Siddle KJ, Matranga CB, Bankamp B, Hennigan S, Sabina B, Byrne EH, McNall RJ, Shah RR, Qu J, Park DJ, Gharib S, Fitzgerald S, Barreira P, Fleming S, Lett S, Rota PA, Madoff LC, Yozwiak NL, MacInnis BL, Smole S, Grad YH, Sabeti PC. 2020. Combining genomics and epidemiology to track mumps virus transmission in the United States. PLoS Biol 18:e3000611. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stapleton PJ, Eshaghi A, Seo CY, Wilson S, Harris T, Deeks SL, Bolotin S, Goneau LW, Gubbay JB, Patel SN. 2019. Evaluating the use of whole genome sequencing for the investigation of a large mumps outbreak in Ontario, Canada. Sci Rep 9:12615. 10.1038/s41598-019-47740-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rota JS, Rosen JB, Doll MK, McNall RJ, McGrew M, Williams N, Lopareva EN, Barskey AE, Punsalang A, Jr, Rota PA, Oleszko WR, Hickman CJ, Zimmerman CM, Bellini WJ. 2013. Comparison of the sensitivity of laboratory diagnostic methods from a well-characterized outbreak of mumps in New York city in 2009. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20:391–396. 10.1128/CVI.00660-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubota M, Takeuchi K, Watanabe S, Ohno S, Matsuoka R, Kohda D, Nakakita SI, Hiramatsu H, Suzuki Y, Nakayama T, Terada T, Shimizu K, Shimizu N, Shiroishi M, Yanagi Y, Hashiguchi T. 2016. Trisaccharide containing alpha2,3-linked sialic acid is a receptor for mumps virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:11579–11584. 10.1073/pnas.1608383113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boddicker JD, Rota PA, Kreman T, Wangeman A, Lowe L, Hummel KB, Thompson R, Bellini WJ, Pentella M, Desjardin LE. 2007. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for detection of mumps virus RNA in clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 45:2902–2908. 10.1128/JCM.00614-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dilcher M, Barratt K, Douglas J, Strathdee A, Anderson T, Werno A. 2018. Monitoring viral genetic variation as a tool to improve molecular diagnostics for mumps virus. J Clin Microbiol 56:e00405-18. 10.1128/JCM.00405-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gouma S, Vermeire T, Van Gucht S, Martens L, Hutse V, Cremer J, Rota PA, Leroux-Roels G, Koopmans M, van Binnendijk R, Vandermarliere E. 2018. Differences in antigenic sites and other functional regions between genotype A and G mumps virus surface proteins. Sci Rep 8:13337. 10.1038/s41598-018-31630-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyoty H, Parkkonen P, Rode M, Bakke O, Leinikki P. 1993. Common peptide epitope in mumps virus nucleocapsid protein and MHC class II-associated invariant chain. Scand J Immunol 37:550–558. 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1993.tb02571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peltola H, Kulkarni PS, Kapre SV, Paunio M, Jadhav SS, Dhere RM. 2007. Mumps outbreaks in Canada and the United States: time for new thinking on mumps vaccines. Clin Infect Dis 45:459–466. 10.1086/520028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flygare S, Simmon K, Miller C, Qiao Y, Kennedy B, Di Sera T, Graf EH, Tardif KD, Kapusta A, Rynearson S, Stockmann C, Queen K, Tong S, Voelkerding KV, Blaschke A, Byington CL, Jain S, Pavia A, Ampofo K, Eilbeck K, Marth G, Yandell M, Schlaberg R. 2016. Taxonomer: an interactive metagenomics analysis portal for universal pathogen detection and host mRNA expression profiling. Genome Biol 17:111. 10.1186/s13059-016-0969-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kontio M, Jokinen S, Paunio M, Peltola H, Davidkin I. 2012. Waning antibody levels and avidity: implications for MMR vaccine-induced protection. J Infect Dis 206:1542–1548. 10.1093/infdis/jis568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vygen S, Fischer A, Meurice L, Mounchetrou Njoya I, Gregoris M, Ndiaye B, Ghenassia A, Poujol I, Stahl JP, Antona D, Le Strat Y, Levy-Bruhl D, Rolland P. 2016. Waning immunity against mumps in vaccinated young adults, France 2013. Euro Surveill 21:30156. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.10.30156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homan EJ, Bremel RD. 2014. Are cases of mumps in vaccinated patients attributable to mismatches in both vaccine T-cell and B-cell epitopes? An immunoinformatic analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother 10:290–300. 10.4161/hv.27139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivancic-Jelecki J, Santak M, Forcic D. 2008. Variability of hemagglutinin-neuraminidase and nucleocapsid protein of vaccine and wild-type mumps virus strains. Infect Genet Evol 8:603–613. 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasheed MAU, Hickman CJ, McGrew M, Sowers SB, Mercader S, Hopkins A, Grimes V, Yu T, Wrammert J, Mulligan MJ, Bellini WJ, Rota PA, Orenstein WA, Ahmed R, Edupuganti S. 2019. Decreased humoral immunity to mumps in young adults immunized with MMR vaccine in childhood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:19071–19076. 10.1073/pnas.1905570116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin SA, Qi L, Audet SA, Sullivan B, Carbone KM, Bellini WJ, Rota PA, Sirota L, Beeler J. 2008. Antibody induced by immunization with the Jeryl Lynn mumps vaccine strain effectively neutralizes a heterologous wild-type mumps virus associated with a large outbreak. J Infect Dis 198:508–515. 10.1086/590115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam E, Rosen JB, Zucker JR. 2020. Mumps: an update on outbreaks, vaccine efficacy, and genomic diversity. Clin Microbiol Rev 33:e00151-19. 10.1128/CMR.00151-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]