Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to qualitatively explore perceptions related to COVID-19 vaccination intention among African American and Latinx participants and suggest intervention strategies.

Approach:

Ninety minute virtual focus groups (N = 8), segmented by county, race and ethnicity were conducted with stakeholders from 3 vulnerable Alabama counties.

Participants:

Participants (N = 67) were primarily African American and Latinx, at least 19 years, and residents or stakeholders in Jefferson, Mobile, and Dallas counties.

Setting:

Focus groups took place virtually over Zoom.

Methods:

The semi-structured guide explored perceptions of COVID-19, with an emphasis on barriers and facilitators to vaccine uptake. Focus groups lasted approximately 90 minutes and were audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed by a team of 3 investigators, according to the guidelines of Thematic Analysis using NVivo 12. To provide guidance in the development of interventions to decrease vaccine hesitancy, we examined how themes fit with the constructs of the Health Belief Model.

Results:

We found that primary themes driving COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, ordered from most to least discussed, are mistrust, fear, and lack of information. Additionally, interventions to decrease vaccine hesitancy should be multi-modal, community engaged, and provide consistent, comprehensive messages delivered by trusted sources.

Keywords: COVID-19, vaccine hesitancy, qualitative research, health disparities

Purpose

Early in 2020, the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic associated with the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Immediately following the initial outbreaks, scientists began work to accelerate the development of vaccines against COVID-19.1 Historically, vaccines can take 10–12 years to develop, and only 6% of the candidate vaccines reach the market.2 However, 1 year after the pandemic’s onset, more than 230 COVID-19 vaccines have been developed globally at record rates, with 172 in preclinical development, 60 in clinical development, and 9 approved for distribution.3 At the time of writing, three vaccines have been authorized for emergency use in the United States: the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine, Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, and Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 Vaccine.4

Even with regulatory assurances, many individuals are hesitant about taking vaccines. In fact, in 2019, vaccine hesitancy was named as one of the ten threats to global health.5 Vaccine hesitancy is a complex and context-specific construct that is influenced by trust in the efficacy and efficiency of vaccines, in the systems that deliver vaccines, and in the motivations of policymakers or others who decide whether vaccines are needed or not. Decisions to vaccinate are also dependent on perceptions of risk and ability to access a vaccine.6,7 Many studies identify racial, ethnic, and sociodemographic differences in attitudes toward vaccines.7–11 For example, a recent social media study in the United States reported that individuals who were socioeconomically disadvantaged and lived in the Southeast had a lower vaccine acceptance rate compared to their counterparts.12

Among African Americans, medical mistrust due to historical mistreatment additionally impacts the decision to seek medical care,13 including treatment and vaccines. Vaccine hesitancy among vulnerable groups could exacerbate existing COVID-19 disparities. COVID-19’s toll on communities throughout the United States is especially devastating in vulnerable populations, including racial or ethnic minority groups. While African American and Latinx people have, respectively, 1.1 and 2.0 higher risk of being diagnosed with COVID-19 than non-Hispanic Whites, they are hospitalized at 2.8 and 3.0 times higher rates and die from the disease at 1.9 and 2.3 times higher rates than their White counterparts.14

A review of published studies on addressing vaccine hesitancy concluded that there was little evidence of successful strategies to support uptake.15 Still, the most successful public health interventions are those that consider the values, concerns, and barriers among communities and individuals.16,17 The purpose of this study was to explore perceptions related to COVID-19 vaccine intention among African American and Latinx community members and stakeholders across 2 urban counties and 1 rural county in Alabama, and to suggest potential intervention strategies based on these perceptions. This work was done through a substudy of the Alabama Community Engagement Alliance against COVID-19 (AL CEAL), part of a nationwide initiative funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Design

Virtual focus groups were used for this qualitative study. Alabama Community Engagement Alliance against COVID-19 leveraged established local partnerships through which potential participants were informed of the study. Participants were recruited by trained research staff via e-mail and phone calls. Staff used telephone/e-mail scripts to explain the study, determine eligibility, and invite individuals to attend a focus group to discuss COVID-19.

Participants

Participants were residents or stakeholders in Dallas (rural), Jefferson (urban), or Mobile County (urban), Alabama, at least 19 years of age and had the ability and access to log into a Zoom meeting online. Stakeholders were defined as individuals who lived, worked, volunteered, and/or held a leadership position in the communities they represented. Counties were chosen to represent different geographic areas of the state, based on existing partnerships and infrastructure to conduct research and implement interventions. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, protocol # IRB-300006220.

Methods

Data Collection

Focus groups were conducted in December 2020. Focus groups included 6–10 participants each and were segmented by county, race, and ethnicity. Following current social distancing and public health guidelines, organizers utilized the online digital meeting platform, Zoom. An IRB-approved information sheet and a link to a secure Zoom meeting was sent to the participants at least 48 hours prior to the focus group. The information sheet was read at the beginning of the zoom meeting and participants gave verbal consent and were given the opportunity to logout if they chose not to participate. Each focus group lasted approximately 90 minutes and was led by race/ethnic-concordant staff trained in moderation skills. A focus group guide explored sources of information and perceptions of COVID-19, with a specific emphasis on barriers and facilitators to vaccine uptake. Participants were given the opportunity to diverge from the guide; themes brought up by participants could be explored in subsequent focus groups. All participants received a $50 incentive for participation.

Data Analysis

Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed. A team of 3 analysts worked together to code and analyze the transcripts according to the guidelines of Thematic Analysis.18 Two of the analysts (LB and AH) read through the transcripts independently to develop a broad coding structure, then met to reconcile their coding structures into a single codebook. After the coding agreement was established, transcripts were divided between 3 coders (LB, AH, and CO). To enhance validity and rigor, each transcript was coded by a primary coder and reviewed by a secondary coder for interrater reliability. The coders made annotations to identify points of discussion and emerging themes. Themes were included in the manuscript and health belief model (HBM) only if they have been discussed by a several participants and most of the focus groups (4 or more). When all data were coded, the analysts (LB and AH) independently examined the themes and their fit within the HBM, then jointly developed a conceptual model from these themes. Data were analyzed using NVivo 12.

The HBM, one of the most broadly used conceptual frameworks in health promotion research,19,20 including vaccine intention and uptake studies,11,21–24 informed the study design and the interpretation of the findings. The HBM posits that individuals will take action (i.e., get a vaccine) to prevent a particular disease if they (a) consider themselves at risk (perceived susceptibility); (b) fear that the disease can have serious consequences (perceived severity); (c) perceive that taking part in specified behaviors will be beneficial for reducing the susceptibility to and/or the severity of the condition; and (d) believe that the benefits outweigh the barriers.20 Modifying variables, such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and educational attainment, are crucial to the manner in which the other constructs of the model are perceived.19

Results

A total of 8 focus groups with a total of 67 participants were conducted: 3 each in Jefferson and Mobile Counties, and 2 in Dallas County. Six focus groups were primarily African American, and 2 were Latinx. The demographic makeup of focus groups is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 67)

| Jefferson County focus groups |

Mobile County focus groups |

Dallas County focus groups |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | AA1 | Latinx | AA2 | AA1 | Latinx | AA2 | AA1 | AA2 |

| Participants, N | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| Female sex, N (%) | 7 (78%) | 6 (75%) | 6 (67%) | 7 (88%) | 6 (75%) | 7 (78%) | 5 (71%) | 7 (78%) |

| AA race, N (%) | 9 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (89%) | 8 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (89%) | 7 (100%) | 9 (100%) |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Age, mean (range) | 55. 9 (28–76) | 52.8 (27–63) | 42.3 (28–54) | 52.4 (22–71) | 46.6 (26–77) | 52.3 (31–68) | 38.4 (24–57) | 45.2 (29–68) |

COVID-19 Vaccine Intention

When asked, “If a vaccine for COVID-19 were to become available, that could likely prevent you from getting infected, would you get it?” most were unsure and responded that they would wait to see if it were safe and without long-term effects, based on others taking it first. For example, one participant stated, “I don’t feel I need to rush into takin’… a vaccine right now. I would just wait and see what would be happening and… look around the world and see what’s goin’ on” (African American, Dallas County).

Major Themes Related to Vaccine Hesitancy

Three primary themes emerged in relation to the expressed vaccine hesitancy (ordered from most to least discussed): mistrust, fear, and lack of information.

Theme 1. Mistrust: “I’m Not Gonna be a Guinea Pig.” (Jefferson County, African American)

Stoked by misinformation, mixed messages, lack of information, and suspicion based on historical injustices, mistrust led to deeply felt fear and vaccine hesitancy. Three subthemes related to mistrust were identified: historical mistrust, vaccine development mistrust, and mistrust of politicians.

Subtheme 1: Historical Mistrust.

Deep mistrust based on systemic racism and historical mistreatment of African Americans was evident in all groups, including the Latinx groups. For example, every focus group mentioned Tuskegee or “experimentation on African American people,” and the term “guinea pig” was used repeatedly. One Dallas County African American participant stated, “Well, I have one phrase, the Tuskegee experiment.” Another mentioned, “I don’t think there would be anything that would encourage people from this area to be, quote/unquote, guinea pigs. We’ve seen the history, what has happened…”

Subtheme 2: Vaccine Development Mistrust.

The historical mistrust spilled over into vaccine development mistrust, and participants perceived being vaccinated against COVID-19 as being a guinea pig or a “test rat.” Mistrust and concerns about rushed vaccine development resulted in participants questioning the vaccine’s efficacy and potential side effects that might emerge years later. Most groups mentioned that they did not trust the vaccine because it has been developed so quickly. Further, most groups wondered if the vaccine would work, since they had no proof. For example, a Jefferson County African American participant stated, “A lot of people look at vaccines as just experiments… we don’t know if this is really gonna work.” Finally, all groups discussed that they did not trust the vaccine because there could be unintended side effects later on, such as one participant who stated, “I would not be first in line to get it. I’d have to let thousands of Americans get it before—and I see their reaction before I get it.” (Mobile County, African American).

Subtheme 3: Mistrust of Politicians.

When asked about information sources that people do NOT trust, a few participants mentioned specific radio or television stations and social media, but all brought up politicians or the government, and most groups mentioned the president by name, as discussed by this Jefferson County, African American participant, “I think it should’ve started from the top, as far as the president should’ve set the tone for everyone. I think we should have been given the correct information.”

Theme 2. Fear: “Most of the People Are Very Scared.” (Jefferson County, African American)

Fear emerged as a major theme and included three subthemes: fear of exposure, fear of the unknown, and, for undocumented people, fear of deportation.

Subtheme 1: Fear of Exposure.

All focus groups discussed the debilitating fear of getting exposed to COVID-19 and contracting the virus, particularly due to its deadly nature and knowing people who had died of it. Participants mentioned family, friends, and community members who had passed away due to COVID-19. For example, a Mobile County African American participant stated, “We have had maybe 3 or 4 classmates to pass away from it, from this deadly disease, and we just don’t know how to handle it.” Fear was amplified among older people, and made them avoid doctor’s offices, gyms, and social experiences, and led to individuals following COVID-19 public health guidelines, such as mask wearing and social distancing.

Subtheme 2: Fear of the Unknown.

The unknown nature of the novel coronavirus and the uncertainty associated with COVID-19 (stemming from misinformation or lack of information) made the fear worse. For example, one participant stated, “We’ve never had anything like this, and it’s just the unknown” (Dallas County, African American). All focus groups also expressed fear over potential unknown side effects of the vaccine that could emerge later, and this fear was a significant barrier to vaccine uptake.

Subtheme 3: Fear of Deportation.

Fear of deportation due to undocumented status was discussed in both Latinx groups. This fear made individuals avoid situations where they would have to give too much information, such as testing, contract tracing, or even getting a vaccine. As stated by a Jefferson County Latinx participant: “For so many people, you’re like a sitting duck. If you go to a particular place… they could think, ‘If I go to that place, I will get the vaccine, but probably I will get something more, like arrested or deported or something.’”

Theme 3. Information: “Knowledge is Power.” (African American, Jefferson County)

Information emerged as a major theme, both as a barrier (not enough information or misinformation) and a facilitator (comprehensive, correct information) to vaccine uptake.

Subtheme 1: Lack of Information.

Almost all groups mentioned that the lack of information and misinformation were major barriers to practicing COVID-19 prevention behaviors and testing. This extended also to the potential vaccine uptake, as seen in this quote from a Jefferson County, African American participant, “I wouldn’t recommend anyone to take it, especially the people I care about, until I actually know does it really help people.”

Subtheme 2: Correct and Complete Information.

Participants across all focus group agreed that what was needed to counter mistrust was information from trusted sources. The public had to be educated about COVID-19 and the vaccine. For example, a Jefferson County African American participant shared, “Knowledge is power. When we become more knowledgeable about what we’re taking and why, then we’ll be more apt to want to do it. Provide us with more information on what is being done and what has been done in other areas, and not make us feel like we’re the guinea pigs.” Similar sentiment was shared by a Dallas County participant, “You can’t just tell people to just take a vaccine. You have to educate them around it, and it has to be people who are from your community that you can trust to overcome these hurdles.” In fact, those who said they would get the vaccine or participate in a clinical trial were motivated by exposure to scientific information about the vaccine and trust in the scientific process. A Jefferson County Latinx participant shared it this way: “I trust the FDA and I know they are not going to approve a vaccine that is going to hurt us.”

Health Belief Model and Vaccine Hesitancy

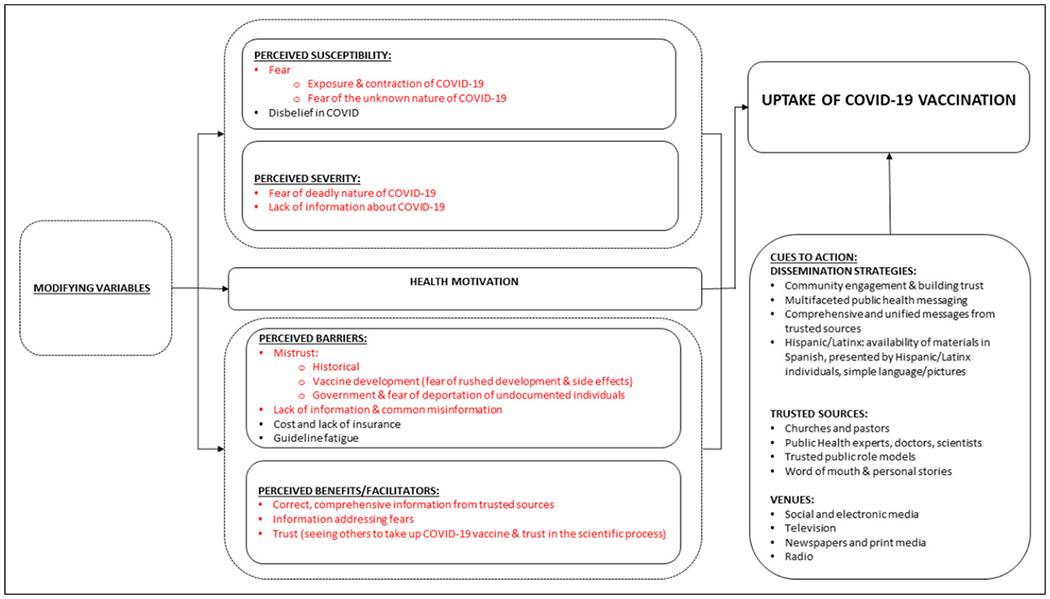

After themes were identified, the investigators explored how they fit with the constructs of the HBM in order to understand vaccine hesitancy related to COVID-19 and to design effective interventions. Content related to perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, barriers, facilitators, and cues to action was identified (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Vaccine hesitancy through the lens of the health belief model.

Perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 was indicated by discussions of fear of contracting COVID-19 (see fear theme) and following prevention behaviors, such as mask wearing and isolation/social distancing (secondary themes). Participants also discussed that those who thought that COVID-19 is a “hoax” ignored prevention guidelines, and may avoid the vaccine as well. For example, a Jefferson County African American participant stated, “I don’t see how they’re gonna get those people to believe in the vaccine for the virus that they don’t believe in.”

Perceived severity of COVID-19 was evidenced by fear of the deadly nature of COVID (see fear theme). However, misinformation and lack of information may lead people to believing that they would not experience severe symptoms if they contracted COVID-19. As stated by one Dallas County African American participant: “A lotta people are actually seeing it as, ‘Well, I’m not gonna get sick from it because I don’t have an underlying health condition.’ Just misinformation, miscommunication.”

Barriers.

Primary barriers to vaccine uptake were mistrust and lack of information as discussed above. Secondary barriers included cost and lack of insurance.

Facilitators of vaccine uptake included renditions of the three primary themes: information, fear, and trust. Trust in the scientific process as well as seeing trustworthy people taking the vaccine were mentioned as powerful facilitators, as shown in this quote from a Mobile County Latinx participant: “Just havin’ authority figures telling us that this is good for us and showing us… bein’ vaccinated… That’s the best way to actually carry the message.” As noted above, for those who said they would get the vaccine or participate in a clinical trial, the most cited motivation was their exposure to scientific information about the vaccine and trust in the scientific process.

Cues to Action: COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Intervention Development.

Cues to action in the HBM are conceptualized as factors that can trigger the behavior, such as media awareness campaigns.19 Such factors are important to consider in the design of interventions to decrease COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Findings from this study indicate that vaccine hesitancy interventions must focus on decreasing mistrust, decreasing fear, and dissemination of correct, timely, and complete information from trusted sources in the targeted communities.

Dissemination Strategies.

Participants claimed that an intervention to decrease vaccine hesitancy has to be multi-modal, include different organizations and venues, be community engaged, and provide consistent and comprehensive messages, with comprehensive meaning information that provides sufficient detail to allow individuals to make the best decisions for them. Latinx groups specifically suggested that simple messages using more pictures than words and presented in Spanish by people who looked like them were important to increase impact. When asked about trusted sources of information, participants’ most common response across all focus groups was pastors and churches. These were followed by public health experts, doctors, and scientists. Participants agreed that there are trusted public figures unique to each community, from artists and social media influencers for young people, to local doctors known and trusted by community members. Social and electronic media were discussed most often in terms of venues where people in the community got their information, followed by television, newspapers, print media, and radio.

Conclusion

In this qualitative study of African American and Latinx participants from vulnerable communities in Alabama, we found that three primary themes drive COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: mistrust, fear, and misinformation. Examining these themes through the lens of the HBM, we were able to determine how they are reflected in the constructs of the HBM—perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, barriers, facilitators, and cues to action—and identify modifying factors (See Figure 1). We further suggest cues to action that could inform intervention development.

Other studies have used the HBM as a lens through which to view COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy,11,24,25 although findings vary by study population. This is not surprising, as trust in any vaccine depends on local norms, attitudes, and beliefs.26 Therefore, examining vaccine hesitancy among specific population groups is crucial for developing effective, targeted interventions.

The primary themes that emerged—mistrust, fear, and misinformation—are not surprising. Vaccine hesitancy has been an issue in the U.S. even before COVID-19, and mistrust is central to this problem. According to Larson et al, the decision for an individual to take a vaccine involves trust at multiple levels: trust in the vaccine product, in the provider who administers the vaccine, and in government regulatory processes.26,27 We identified these forms of mistrust in our study, labeled as historical mistrust (healthcare system and policy makers), mistrust of politicians (policy makers), and vaccine development mistrust (vaccine product). We also identified doctors as trusted information sources (provider).

Medical mistrust, combined with stigma and decreased likelihood of referrals for COVID-19 testing, has contributed to decreased engagement of African Americans with the healthcare system.28 A recent pilot study on COVID-19 perspectives among African Americans in low-income communities in Birmingham, Alabama, identified mistrust of medical providers and COVID-19 messaging as a major theme.29 This mistrust often stems from systemic racism, which contributes to vaccine hesitancy,30 and can be traced back to medical maltreatment experienced by previous generations, including the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, as well as medical experimentation during slavery.31–33

The decision to take or not take a vaccine is also influenced by sources outside of the healthcare system and the government. Influencers, such as family, friends, and religious leaders may play a significant role in vaccine uptake, to the extent that individuals believe their intentions and have a history of receiving reliable and/or competent information from them26 This study found that trusted sources of vaccine-related information included friends, family, and faith leaders. For successful interventions intended to increase vaccine uptake among racial/ethnic minority groups, racial trauma and distrust of healthcare and government systems must be addressed.34 Since this is a daunting task without a quick solution, the most effective immediate strategy in the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic may be to focus on other forms of mistrust, such as in the vaccine product itself, with messages delivered by trusted sources. And, because pastors are critical among trusted sources, targeting community engagement efforts to local faith leaders and providing them with correct, updated information and reassurance may be the key to engendering trust among their congregations.

Fear also emerged as a primary theme in this study, which is not surprising given the deadly nature of the COVID-19 pandemic.35 Early in the pandemic, studies identified fear linked to the uncertainty of individual and societal consequences from COVID-19, and some investigators suggested that the U.S. is on the verge of a public health crisis in mental health.36,37 Understanding fears associated with COVID-19 is critical to designing effective interventions targeting specific groups, and quantitative scales have been developed to assess levels of fear and aid in prevention efforts.38 In fact, one survey study found that when assessing the role of individual differences in predicting preventive behaviors, the only significant variable that predicted behavior change, or following public health guidelines, was fear.39 The authors, therefore, concluded that fear could be both normative and protective.39 Our findings also indicate that fear of COVID-19 may lead to uptake of preventive behaviors, both in this study and a previous study.29 More research on the role of fear in vaccine uptake and hesitancy is needed, especially related to COVID-19.

We also found that misinformation and contradictory information may hamper preventive efforts, including COVD-19 vaccine uptake, which corroborates previous reports.29 Further, Jones et al found that Hispanics and African Americans had less knowledge about COVID-19 infection and prevention than non-Hispanic White and Asian participants, which contributes to disparities in COVID-19.40 It has been suggested that research to identify sources of information that are trusted by African American and Latinx communities is needed in order to design effective information dissemination interventions.40 Our paper responds to this gap in knowledge by identifying several trusted sources such as churches and pastors; doctors, scientists, and public health experts; and public figures unique to each community, known and trusted by community members.

Finally, examining how our identified themes fit with the HBM in terms of perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, barriers, facilitators, and cues to action provides guidance in the development of effective community outreach programs to decrease vaccine hesitancy.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. This study looks at a unique group of people, stakeholders, and although many participants lived in the communities they represented, most were community leaders and speaking on behalf of their community members. Residents in vulnerable communities who are not leaders may have different perspectives. Future research in this area could examine the susceptibility, severity, barriers, facilitators, and cues to action of other groups as well as the impact of demographic variables such as socioeconomic status, age, sex, and rurality. Further, Latinx groups were conducted in English, and discussions may have been more nuanced if they were held in Spanish. Finally, focus groups were conducted during the first week of December 2020, just prior to any vaccines being approved for emergency use by the FDA. Sentiments may have changed after the vaccine approval, and these perceptions and attitudes need to be studied to discover reasons for potential changes in hesitancy toward more acceptance.

So What?

What is already known on this topic?

Vaccine hesitancy, a critical public health issue even before 2020, continues with COVID-19 vaccines. As a complex and context-specific construct, vaccine hesitancy is influenced by many sources and could exacerbate existing COVID-19 disparities among vulnerable populations.

What does this article add?

In this focus group study of African American and Latinx participants representing vulnerable communities in Alabama, we identified three primary themes—mistrust, fear, and misinformation—that contribute to the constructs of the HBM in relation to vaccine hesitancy.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy interventions for low-income African American and Latinx communities should focus on decreasing mistrust, decreasing fear, and providing correct, timely, and comprehensive information, delivered by trusted sources, and in sufficient detail to enable individuals to make the best decisions for themselves and their families.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kimberly Speights and Grace Okoro (UAB Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Center) and Cathy Cartagena and Maria I. Hoyos-Hernandez (UAB Recruitment and Retention Service Facility) for their assistance in focus group moderation.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded through a grant from NHLBI, # OT2HL156812, through a subcontract with Research Triangle Institute (Lead Principal Investigator: Mona N. Fouad)

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), protocol # IRB-300006220

References

- 1.Bloom DE, Cadarette D, Ferranna M, Hyer RN, Tortorice DL. How new models of vaccine development for COVID-19 have helped address an epic public health crisis. Health Aff. 2021; 40(3):410–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pronker ES, Weenen TC, Commandeur H, Claassen EH, Osterhaus AD. Risk in vaccine research and development quantified. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashte S, Gulbake A, El-Amin SF Iii, Gupta A. COVID-19 vaccines: rapid development, implications, challenges and future prospects. Hum Cell. 2021;34:711–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.FDA. COVID-19 Vaccines. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2021. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines. Accessed March 1, 2021.

- 5.WHO. Ten threats to global health in 2019. 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- 6.MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015;33(34):4161–4164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinn SC, Jamison A, Freimuth VS, An J, Hancock GR, Musa D. Exploring racial influences on flu vaccine attitudes and behavior: results of a national survey of White and African American adults. Vaccine. 2017;35(8):1167–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn S, Jamison A, Musa D, Hilyard K, Freimuth V. Exploring the continuum of vaccine hesitancy between African American and white adults: results of a qualitative study. PLoS Curr. 2016;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham RM, Minard CG, Guffey D, Swaim LS, Opel DJ, Boom JA. Prevalence of vaccine hesitancy among expectant mothers in houston, Texas. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmid P, Rauber D, Betsch C, Lidolt G, Denker ML. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior - A systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005 - 2016. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercadante AR, Law AV. Will they, or Won’t they? Examining patients‘ vaccine intention for flu and COVID-19 using the Health Belief Model. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;17:1596–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyu H, Wu W, Wang J, Duong V, Zhang X, Luo J. Social Media Study of Public Opinions on Potential COVID-19 Vaccines: Informing Dissent, Disparities, and Dissemination. arXiv preprint arXiv:201202165; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams DR, Cooper LA. COVID-19 and health equity—a new kind of “herd immunity”. Jama. 2020;323(24):2478–2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html#print. Accessed April 30, 2021.

- 15.Dube E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE, Hesitancy SWGoV. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: Review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4191–4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman MT, Pasternak RH. Effective strategies for behavior change. Prim Care Clin Off Pract. 2012;39(2):281–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poland B, Krupa G, McCall D. Settings for health promotion: an analytic framework to guide intervention design and implementation. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10(4):505–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic analysis. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Singapore: Springer; 2019:843–860. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Champion VL, Skinner CS. The health belief model. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008:45–65. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenstock IM. The Health Belief Model: Explaining health behavior through expectancies. In Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK (Eds). Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1990: 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coe AB, Gatewood SB, Moczygemba LR, Goode JV, Beckner JO. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the novel (2009) H1N1 influenza vaccine. Innov Pharm Technol. 2012;3(2):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mo PKH, Lau JTF. Influenza vaccination uptake and associated factors among elderly population in Hong Kong: the application of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Res. 2015;30(5):706–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fall E, Izaute M, Chakroun-Baggioni N. How can the health belief model and self-determination theory predict both influenza vaccination and vaccination intention? A longitudinal study among university students. Psychol Health. 2018;33(6):746–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruiz JB, Bell RA. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine. 2021; 39(7):1080–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong LP, Alias H, Wong P-F, Lee HY, AbuBakar S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16(9):2204–2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, et al. Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14(7):1599–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson HJ, Schulz WS, Tucker JD, and Smith DM. Measuring vaccine confidence: introducing a global vaccine confidence index. PLoS currents 2015;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nydegger LA, Hill MJ. Examining COVID-19 and HIV: The impact of intersectional stigma on short-and long-term health outcomes among African Americans. Int Soc Work. 2020;63(5): 655–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bateman LB, Schoenberger YM, Hansen B, Osborne TN, Okoro GC, Speights KM, and Fouad MN. Confronting COVID-19 in under-resourced, African American neighborhoods: a qualitative study examining community member and stakeholders’ perceptions. Ethnicity & health 2021;26(1):49–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogart LM, Ojikutu BO, Tyagi K, et al. COVID-19 related medical mistrust, health impacts, and potential vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(2):200–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Washington HA. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Doubleday Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore AD, Hamilton JB, Knafl GJ, et al. The influence of mistrust, racism, religious participation, and access to care on patient satisfaction for African American men: the North Carolina-Louisiana Prostate Cancer Project. J Natl Med Assoc. 2013;105(1):59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dale SK, Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Klein DJ. Medical mistrust is related to lower longitudinal medication adherence among African-American males with HIV. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(7):1311–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lackland DT, Sims-Robinson C, Jones Buie JN, Voeks JH. Impact of COVID-19 on clinical research and inclusion of diverse populations. Ethn Dis. 2020;30(3):429–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD. The fear of COVID-19 and its role in preventive behaviors. Journal of Concurrent Disorders. 2020; 2(1):58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzpatrick KM, Harris C, Drawve G. Fear of COVID-19 and the mental health consequences in America. Psychological Trauma. 2020;12:S17–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panchal N, Kamal R, Orgera K, et al. The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, and Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addiction 2020;1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harper CA, Satchell LP, Fido D, and Latzman RD. Functional fear predicts public health compliance in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Addiction 2020;1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones J, Sullivan PS, Sanchez TH, et al. Similarities and differences in COVID-19 awareness, concern, and symptoms by race and ethnicity in the United States: cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(7):e20001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]