Abstract

Magnetic nanoparticles with hybrid sensing functions are in wide use for bioseparation, sensing, and in vivo imaging. Yet, nonspecific protein adsorption to the particle surface continues to present a technical challenge and diminishes the theoretical protein detection capabilities. Here, a magneto-plasmonic nanoparticle synthesis is developed that minimizes nonspecific protein adsorption. Building on the success of zwitterionic polymers, a highly stable and anergic nanomaterial, magnetic gold nanoparticles with idealized coating (MAGIC) is obtained with significantly lower serum protein adsorption compared to control nanoparticles coated with commonly used polymers (polyethylene glycol, polyethylenimine, or polyallylamine hydrochloride). MAGIC nanoparticles are able to sense specific bladder cancer biomarkers at low levels and in the presence of other proteins. This strategy may find wide spread applications for in vitro and in vivo sensing as well as isolations.

Keywords: magnetic, nanoparticles, plasmonic, point-of-care diagnostics, polymers, zwitterions

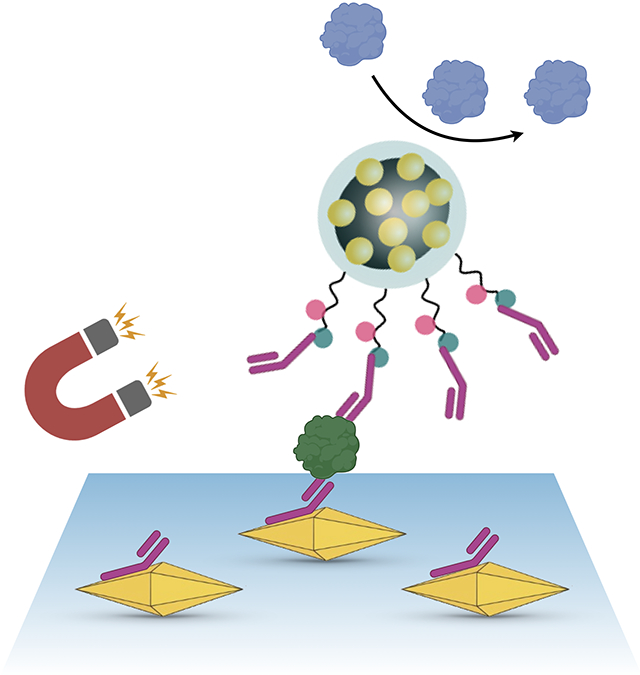

Graphical Abstract

Nonspecific protein adsorption continues to present a technical challenge and diminishes the theoretical protein detection capabilities of nanotechnological sensors. Here, dispersible electrodes composed of magneto-plasmonic nanoparticles are presented which possess an antifouling coating and demonstrate high sensitivity and selectivity towards circulating biomarkers, in this case bladder cancer related proteins in urine.

1. Introduction

Point-of care sensing of disease biomarkers is gaining traction for early disease detection, longitudinal surveillance, monitoring of therapeutic side effects, and prognostication. A myriad of analytical technologies have been advocated differing in sensitivity, specificity, turnaround time, signal detection, and their ability to be integrated into a digital healthcare environment.[1] Plasmonic sensing in particular is emerging as a potent method as it offers exquisite sensitivity, high-throughput operation, and ease of integration into portable devices (e.g., smartphones).[2-4] In its simplest form, detection is performed directly on a metallic surface,[3] whereas ultrasensitive detection schemes often add inorganic nanomaterials for additional amplification steps.[5] Gold and other novel metal nanoparticles have both been described in this regard while hybrid materials[6-8] offer helpful one-step systems for purification and sensing. We and others have also described plasmonic nanomaterials to enhance analytical signal.[9] While the previously described materials proved useful, they also often show nonspecific protein adsorption to the hybrid materials thus counteracting desirable high signal-to-noise ratios.[10,11] Furthermore, these particles generally recognize molecular targets through passive diffusion, which leads to slow assay kinetics, particularly for surface-based sensing methods.[12]

We hypothesized that hybrid gold magnetic nanoparticles could be coated with unique polymers to minimize the formation of a protein corona. It is well established that the polymer coating of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles will result in variable protein coronas depending on polymer composition, layer thickness, and charge. Indeed, this concept has been exploited for plasma protein analysis via mass spectroscopy.[13-15] For targeted analysis however, the goal is to minimize such protein adsorption. In order to provide chemical surface anchors for the latter attachment or target-specific molecules, polymers that contain primary amines (e.g., polyethyleneimine, PEI) or carboxylate groups (e.g., polyacrylic acid) have been widely used for the modification of nanoparticles. However, multiple studies have shown that both, strongly positively and negatively charged particles are prone to opsonization upon contact with, for example, serum proteins.[16,17] In fact, increasing the surface charge density on particles has been shown to lead to increased amounts of adsorbed proteins.[18] In direct comparison, near neutral surface charges have demonstrated lowest nonspecific adsorption of proteins on inorganic nanoparticle surfaces.[19] While polyethylene glycol (PEG) is commonly employed to reduce particle-protein interactions,[20] it is often not sufficient to overcome nonspecific protein adsorption. Furthermore, commonly used PEGs are prone to autoxidation in the presence of oxygen and transition metals which can limit their long-term stability.[21,22] Moreover, PEG-coated nanoparticles tend to aggregate under high salt conditions[23] and direct functionalization of PEG still involves complex chemical reactions.[24] Additionally, PEGylation is often accompanied by an unwanted effect on bioactivity.[25,26] We thus explored the use of zwitterionic polymers as alternative coatings for hybrid magneto-plasmonic amplifier materials. While screening different materials, we identified and optimized a specific new type of material termed magnetic gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) with idealized coating (MAGIC). MAGIC nanoparticles showed very low protein adsorption and allowed detection of specific molecular urinary biomarkers in the presence of other proteins at pg mL−1 levels in minutes.

2. Results

2.1. Modular Design

Scheme 1 summarizes the stepwise approach to the design of the MAGIC particles.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of MAGIC beads.

Magnetic core particles were synthesized through a precipitation reaction starting from an iron(II) salt in the presence of an oxidizer. Citrate-capped AuNPs were then assembled onto the positively charged magnetic cores (MNPs) resulting in hybrid materials (MGNPs). Additional coating of the composites with PEI provided the particles with sufficient stability to be used in the following polymerization steps and avoid their disintegration even upon ultrasonication. PEI-derived abundant surfaces amino groups were then used as anchor points to graft zwitterionic polymers (carboxybetaine brushes; poly-CBMA; poly 2-carboxy-N,N-dimethyl-N-(2′-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl)ethanaminium) onto the particle surface. The prepared MAGIC particles possessed surface carboxylates which could then be used to covalently link antibodies for sensing applications. Scheme 2 details the grafting of the carboxybetaine methacrylate (CBMA) polymer and optimized reaction conditions. While we explored a number of alternative synthesis routes, polymer coatings, and overall designs (see Supporting Information), we settled on this approach because it resulted in highly reproducible, uniform materials with excellent biological properties.

Scheme 2.

Surface modification of MGNP with zwitterionic polymers (MAGIC) and antibodies. MGNPs were modified with PEI to provide surface abundant primary amines which upon reaction with triethylamine (TEA) and α-bromoisobutyryl bromide (BIBB) provided surface-initiated MGNPs-Br. Carboxybetaine methacrylate (CBMA) was polymerized on the surface of MGNPs-Br via surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization (SI-ATRP) using CuBr as catalyst. Antibody attachment was then performed through carbodiimide coupling.

2.2. Characterization of Magnetic Gold Nanoparticles with Idealized Coating

MAGIC nanoparticles and their precursors were characterized by different techniques. Scanning and transmission electron microscopies (SEM/TEM) revealed the nanoparticles to contain an iron oxide core with spherical to octahedral morphology,[27] and surface attached AuNPs. On average, there were ten AuNPs per magnetic nanoparticle, resulting in a mean metal core size of ≈63 nm (Figure 1A,B and Figure S1A, Supporting Information). Size ranges for the different electron dense cores were as follows: MNP (mean: 43.8 ± 4.3 nm), AuNP (mean: 11.4 ± 1.4 nm), and MAGIC (mean: 63.3 ± 7.1 nm).

Figure 1.

Characterization of MAGIC beads. a) SEM of MNPs (left) and MAGIC (right). b) TEM of MNPs (left) and MAGIC (right). c) DLS of AuNPs (red), MNPs (black), and MAGIC (blue). d) UV–vis absorbance of AuNPs (red, λmax = 520 nm), MNPs (black), and MAGIC (blue, λmax = 540 nm). e) Photograph of magnetic separation of aqueous MAGIC dispersion. Scale bars refer to a) 100 nm and b) 50 nm.

The above materials were additionally characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS) to measure overall size of the nanoconstructs including their surface coatings. The DLS measurements yielded the following results: MNP (mean: 73.4 ± 15.0 nm), AuNP (mean: 14.2 ± 3.1 nm), MGNP (mean: 107.2 ± 28.0 nm), and MAGIC (mean: 122.8 ± 31.0 nm). The MAGIC hydrodynamic diameter was naturally larger than the size of the metal core determined by SEM/TEM due to the grafting of the hydrophilic PEI and CBMA polymer brushes on the particle surface. MAGIC particles possessed a dark red/purple color with absorption maximum at 540 nm and demonstrated a slight red-shift compared to the free AuNPs (520 nm) (Figure 1D). The magnetic core allowed for fast collection of particles (≤60 s) under an external magnetic field (Figure 1E).

The formation of MAGIC particles was additionally demonstrated through zeta potential measurements (Figure 2A). Surface decoration of positively charged MNPs (24.5 ± 0.6 mV) with negatively charged AuNPs (−38.9 ± 0.4 mV) resulted in negatively charged MGNPs (−37.1 ± 2.3 mV) which upon modification with PEI provided a positive surface charge (22.4 ± 0.9 mV). Surface grafting of carboxybetaine to the particle surface led to a decrease in zeta potential to slightly negative values of −6.3 ± 0.8 mV. pH dependent zeta potential measurements of MAGIC particles revealed an isoelectric point of 5.4. This resulted in a near neutral surface charge and thus excellent antifouling properties in the physiological range between pH 5 and 7.5 (Figure S1B, Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Protein adsorption onto MAGIC beads. a) Zeta potential of MNPs, AuNPs, MGNPs, MGNPs-PEI, and MAGIC nanoparticles measured in 1 mM PBS, b) FT-IR spectra of MNPs (black), MGNPs-PEI (green), and MAGIC (blue), c) surface adsorbed proteins per mg nanoparticle after incubation with HSA (45 mg mL−1), and d) whole serum. Note the much lower protein adsorption onto MAGIC nanoparticles.

FT-IR measurements of MNP, MGNP, and MAGIC confirmed the successful surface modification of nanoparticles (Figure 2B). While Fe–O bonds are visible in all spectra at 568 cm−1, MNP exhibited a broad shoulder between 700 to 1100 cm−1 which can be attributed to C–H bending and C–N stretching of PEI.[28,29] Additionally, N–H and O–H bending at 1655 and 3500 cm−1 supports the presence of PEI and adsorbed water molecules on the MNP surface. Upon addition of citrate-capped AuNPs, additional bands appeared for MGNPs-PEI at 1080 cm−1 indicative of C–O bonds of citric acid. Moreover, MGNPs-PEI demonstrates –CH3 and –CH2 stretching bands at 2830 and 2900 cm−1, respectively. The C–O band becomes much more pronounced at 1100 cm−1 for MAGIC particles related to the presence of the terminal carboxylate of the carboxybetaine functionality on the particle surface. This is supported by the appearance of additional C═O stretching bands at 1720 and 1449 cm−1.

2.3. Nonspecific Protein Adsorption Is Minimized in Magnetic Gold Nanoparticles with Idealized Coating

While previously published studies often employ 1–10% serum or BSA to evaluate the quality of nonspecific protein adsorption onto nanoparticles, it has also been demonstrated that these concentrations are insufficient to match real complex biofluids.[30] Instead it has been suggested that full strength protein solutions should be employed for testing.[24] Following this recommendation, we first tested nonspecific adsorption of human serum albumin (HSA) onto MAGIC particles at a concentration of 45 g L−1 which represents an average HSA concentration in healthy human plasma (normal range is 34–54 g L−1). At these high albumin concentrations, MAGIC particles exhibited very low nonspecific binding in the range of 10 μg mg−1 nanoparticles (Figure 2C). For additional comparison, we also modified MGNPs with a range of other commonly employed polymers that provide surface functionality including PEI, PEG, and polyallylamine hydrochloride (PAH) (Figure S4, Supporting Information). MGNP-PEI and MGNP-PAH exhibited a more than eight times higher nonspecific HSA binding (>85 μg mg−1 nanoparticles) presumably related to the strong net positive surface charge derived from primary amines (Figure S4A, Supporting Information). As expected, HSA binding was lower with PEGylation (35–40 μg mg−1 nanoparticles), although these levels were still three- to four-fold higher compared to MAGIC nanoparticles. Similar results were observed when undiluted human serum was used instead of HSA. The MAGIC nanoparticles demonstrated an almost fivefold lower nonspecific protein adsorption compared to MGNPs-PEI (Figure 2D).

In contrast to well-known sulfobetaines, carboxybetaines also provide surface functionality for the attachment of antibodies through simple N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) chemistry, which has made them the most attractive among all stealth materials so far.[30] In fact, previous studies have demonstrated that carboxybetaine-modified surfaces retain their antifouling properties even after antibody conjugation and allow for sensitive antigen detection even in complex media.[31]

2.4. Magnetic Gold Nanoparticles with Idealized Coating Nanoparticles Allow for Sensitive Detection of Protein Biomarkers

We next applied MAGIC nanoparticles to sense a model protein biomarker in urine. Nuclear mitotic apparatus protein 1 (NuMA1), a protein elevated in an urothelial cancer, was chosen as an example.[32] We employed a sandwich-type immunoassay (Figure 3A): a glass chip, coated with Au bipyramid nanoparticles, was prepared as a substrate for localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), and MAGIC nanoparticles were used to amplify the LSPR spectral shift. We first tested different types of MAGIC-antibody conjugates. MAGIC particles with half antibodies resulted in large LSPR shift upon target recognition, whereas particles with full length antibodies produced much smaller changes (Figure 3B). The higher signal with half antibodies is likely due to the shorter distance (and hence stronger plasmonic coupling) between the LSPR chip and MAGIC nanoparticles.[9] Quantification of surface-immobilized half antibodies to MAGIC nanoparticles was measured to be 313 per bead which is in close proximity to the theoretical surface capacity of 300 and thus demonstrates high surface coverage of MAGIC beads. Exploiting MAGIC’s magnetic property, we were able to substantially speed up the assay time. For example, even a brief (2 min) application of magnetic fields pulled MAGIC nanoparticles toward the substrate and produced larger (2.3-fold) LSPR shift than 30-min particle incubation without fields. Shifts from nonspecific binding, however, remained low (Figure S5, Supporting Information), demonstrating MAGIC’s excellent antifouling capacity.

Figure 3.

MAGIC application for localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) sensing. a) Assay schematic. A plasmonic chip containing Au bipyramid nanoparticles captured target proteins, and MAGIC nanoparticles amplified LSPR signal through plasmonic coupling. Magnetically pulling MAGIC nanoparticles sped up the second labeling process. NuMA1 was used as a model target. b) Conjugating half antibodies both on Au bipyramids and MAGIC nanoparticles produced larger LSPR signal. Applying magnetic fields (2 min) further enhanced the LSPR shift. c) Titration experiments with PBS and human urine samples. The measured signals were similar between these two media. The limits of detection were 30 pg mL−1 (in PBS) and 73 pg mL−1 (in urine). d) Sensing selectivity. Large LSPR shift occurred only when NuMA1 was present. Interference from other urinary markers was minimal, although these proteins were tenfold more abundant than NuMA1.

We next applied the optimized protocol for NuMA1 quantification. Samples were prepared by spiking varying amounts of NuMA1 proteins into PBS or human urine from healthy donors. With 2-min magnetic pulling, we observed LSPR spectral shifts toward longer wavelength, whose magnitude was concomitant with the increase in NuMA1 concentrations (Figure 3C). Overall, LSPR signals were similar between PBS and human urine samples, reconfirming the antifouling effects of MAGIC conjugates. The limits of detection for NuMA1 were 30 pg mL−1 (in PBS) and 73 pg mL−1 (in urine), about ten times lower than that of conventional ELISA tests (310 ng mL−1). We further confirmed the assay selectivity (Figure 3D).

An important aspect in molecular testing is target specificity in the presence of other proteins. We thus prepared urine samples containing potential interfering proteins including hemoglobin (HgB, 100 ng mL−1), prostate specific antigen (PSA, 100 ng mL−1), or kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM1, 100 ng mL−1). These potentially interfering proteins were tested at 10× more amounts than NuMA1. Interfering proteins alone generated no appreciable signals, and they did not interfere with target-specific detection of NuMA1.

3. Discussion and Conclusion

In the current research we show that MAGIC, magneto-plasmonic nanoparticles, have several useful attributes. Specifically, they i) have much lower nonspecific protein adsorption (corona) compared to conventional nanoparticles, ii) allow attachment of target-specific affinity ligands, and iii) result in high signal-to-noise ratio in a prototypical molecular point-of-care assay.

Iron oxide, gold, and other nanoparticles that come into contact with serum are typically coated with a layer of proteins at the nano-bio interface (protein corona).[33,34] The effects of the protein corona on the behavior of given magnetic nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo are being better understood,[35-38] even indicating differences between in vitro and in vivo settings.[39] Initial studies in the field were largely geared at understanding the protein corona composition[40] and how to minimize “biofouling,” that is, binding of proteins to the nanoparticle surface, to improve circulation times, drug delivery and targeting,[13,41,42] and imaging.[10] Recent studies have demonstrated that the physicochemical properties of the nanoparticle dictate the protein corona.[13,34,39,43] Based on discoveries in polymer drug delivery,[25,44-46] we hypothesized that some of these observations could be translatable to allow reproducible synthesis of new classes of materials that minimize the formation of protein corona around nanoparticles.

Knowledge of the interaction between nanoparticle coating and protein is integral to the design and development of point-of-care biosensors.[47] In contrast to PEG, polyzwitterionic surface coatings follow nature’s adaptation to reduce nonspecific interactions by resembling a polar surface with opposed charges as present in proteins.[48] Additionally, the charged surface provides, compared to PEG, an even stronger hydrophilic surface which creates a dense hydration layer between polymer brushes and renders the surface net repulsive.[49]

In the current study we focused on the model system of carboxybetaine as it is well described[50] and, compared to commonly employed sulfobetaines,[45] offers a simple postmodification with affinity ligands which is a key requirement for sensing applications. CBMA was synthesized through ring-opening reaction of a lactone in the presence of a tertiary amine.[51] Its polymerization was performed on the surface of MGNPs by first introducing bromide functionalities to the particle surface. Surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization (SI-ATRP) then allowed for the controlled surface polymerization of CBMA on MGNPs[52] as demonstrated through DLS, zeta potential, and FT-IR measurements. The resultant MAGIC particles had a mean size of ≈63 nm and possessed a thin layer of polycarboxybetaine brushes on the surface that was invisible in electron microscopic images. Nevertheless, CBMA coating resulted in much lower adsorption of albumin, one of the most abundant serum proteins. It also significantly decreased the binding of proteins from human serum. These findings deepen our understanding of the interaction between the MAGIC sensor and the target protein, and provide important lessons in the scientific design and applications of hybrid biosensors.

We anticipate that future enhancements could further improve the approach. To systematically explore the effects of zwitterionic polymers in hybrid magneto-plasmonic AuNPs, we had to make some choices in the synthesis as the multicomponent system can become quite complex[53] (Figure S6, Supporting Information). These choices were based on our long standing interest in developing biocompatible nanomaterials.[10,54,55] In future research, we hope to explore alternative zwitterionic polymers with further reduced protein binding. It is also possible to tune the plasmonic properties through growth of a gold shell (Figure S6B, Supporting Information). Irrespective of the approach, the current work demonstrates far superior behavior of the MAGIC materials for sensing and may open up new opportunities for point-of-care sensing.

4. Experimental Section

Materials:

Iron(II)sulfate heptahydrate (≥99%, FeSO4·7H2O), potassium nitrate (≥99%, KNO3), sodium citrate dehydrate (≥99%), gold(III) chloride trihydrate (99.9%, HAuCl4·3 H2O), polyethyleneimine (PEI, branched, av. Mn. 25.000), chloroplatinic acid hexahydrate (≥37.5% Pt basis, H2PtCl6·6H2O), sodium borohydride (≥98%, NaBH4), silver nitrate (99%, AgNO3), ascorbic acid (≥99%, AA), cetyl-trimethyl ammonium bromide (≥99%, CTAB), (3-mercaptopropyl)-trimethoxysilane (95%, MPTMS), sulfuric acid (95–98%, H2SO4), hydrogen peroxide (≥30%, H2O2), tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), N-methylmaleimides (97%), 2,2′-bipyridine (≥99%,bpy), copper(I) bromide (99.999%, CuBr), α-bromoisobutyryl bromide (98%, BIBB), EDC (≥98%), N-hydroxysuccinimide (98%, NHS), 2-(N,N′-dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (98%, DMAEM), dimethylformamide (99.8%, anhydrous, DMF), HSA (97%), sodium dodecylsulfate (≥98.5%, SDS), PEG (Mw 8000), and 3K amicon ultra 0.5 mL centrifugal filter were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. Triethylamine (99%, anhydrous, TEA), β-propiolactone (95%), and PAH were obtained from Alfa Aesar, sodium hydroxide (97%, NaOH) from Acros Organics, and iso-propanol (≥ 99.5%, iPrOH) from VWR chemicals. Amino-PEG (mPEG-NH2, MW 5000) was ordered from Nanocs. D2O was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, 0.01 m, w/o calcium and magnesium) was procured from Corning. Whole blood derived pooled human serum was purchased from Innovative Research. In all cases, water referred to MilliQ water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ cm−1 at 25 °C.

Synthesis of Carboxybetaine Methacrylate:

2-Carboxy-N,N-dimethyl-N-(2′-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl)ethanaminium (CBMA) was synthesized according to Zhang et al.[51] In short, 1.52 mL (24 mmol) β-propiolactone dissolved in 10 mL dried acetone were added slowly to 50 mL dried acetone containing 3.4 mL (20 mmol) DMAEM at 0 °C under stirring. The mixture was allowed to warm to 15 °C while stirring for further 12 h. The white precipitate was filtered off, washed with anhydrous acetone and ether, and dried under vacuum to receive CBMA as white powder. 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz): δ 6.13 (s, 1H), 5.75 (s, 1H), 4.62 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 3.77 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 3.65 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 3.17 (s, 6H), 2.71 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 1.91 (s, 3H) (Figure S2, Supporting Information). FT-IR spectroscopy revealed the characteristic bands at 600–1000 cm−1 (C═C and C–H bending), 1138 cm−1 (C–O and C–N stretching), 1364 cm−1 (O–H bending), 1573 cm−1 (C═C stretching), 1700 cm−1 (C═O stretching), and 3300 cm−1 (O–H stretching). (Figure S3, Supporting Information)

Synthesis of Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs):

MNPs were synthesized through precipitation and in situ oxidation of an iron(II) salt in basic conditions, following established protocols with slight modifications.[56] In a 100 mL three-neck round bottom flask, 1.01 g (10 mmol) KNO3 and 800 mg NaOH were dissolved in 90 mL water followed by Argon bubbling for 15 min. Meanwhile, 2.78 g (10 mmol) FeSO4·7H2O were dissolved in 5 mL water, purged with argon for 15 min and added dropwise to the mixture under constant stirring. Then, 5 mL of a 4 g L−1 PEI solution was added and the mixture was heated to 90 °C and left undisturbed for 2 h under argon flow. After cooling to room temperature with an ice-bath, the obtained black MNPs were separated using a magnet and washed three times with water and then stored as 18 mg mL−1 dispersion in water until further use.

Synthesis of Magnetic Gold-Coated Nanoparticles (MGNPs):

AuNPs were synthesized based on a citrate-based reduction.[57] 100 mL of an aqueous 1 mM HAuCl4 was heated to 100 °C before rapid addition of 10 mL 38.8 mM sodium citrate. Heating was continued for further 15 min resulting in a color change from colorless to dark red and the mixture was allowed to cool down to room temperature. Then, 18 mg MNPs dispersed in 10 mL water were added drop-wise under strong stirring and the dispersion was stirred for further 2 h. The formed purple MGNPs were separated using a magnet and washed three times with water. PEI was grafted onto the particle surface by redispersing MGNPs in 50 mL water containing 1 g PEI and heating the mixture to 60 °C for 1 h. Upon cooling to room temperature, obtained particles were separated using a magnet and washed three times with water to remove any unbound PEI. Particles were stored in water as a 1 mg mL−1 dispersion until further use. MGNP-PEG, MGNP-PEG-NH2, and MGNP-PAH were prepared analogously to MGNP-PEI using PEG, mPEG-NH2, and PAH, respectively, instead of PEI.

Synthesis of Magnetic Gold Nanoparticles with Idealized Coating Nanoparticles:

Zwitterionic functionalities were attached to the surface of MGNPs via a SI-ATRP. Therefore, 3 mg MGNPs-PEI were transferred to 2 mL anhydrous DMF and bubbled with argon. Then, 0.35 mL TEA was added under stirring followed by 0.175 mL BIBB at 0°C while purging argon. The mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 12 h. Surface initiated bromide functionalized NPs (MGNPs-Br) were collected using a magnet and washed with copious amounts of DMF to remove any side products and then washed with iso-propanol and water.

For the SI-ATRP, 5 mL water/iso-propanol (4/1) mix was purged with argon for 30 min. NPs were dispersed in 1 mL of the solvent mix and purged with argon for another 15 min. Meanwhile, 240 mg (1.05 mmol) CBMA were mixed with 30 mg (0.21 mmol) CuBr and 68 mg (0.44 mmol) bpy under argon and dissolved in 2 mL solvent mix. After two freeze-pump-thaw cycles, the MGNPs-Br were added dropwise and the mixture was stirred for 16 h under argon. MAGIC particles were collected via magnetic separation followed by washing with iso-propanol and water. Particles were stored in water as a 1 mg mL−1 dispersion.

Particle Characterization:

DLS and zeta potential measurements were performed in 1 mM PBS on a Zetasizer NanoZS (Malvern Analytical) using disposable folded capillary cells. FT-IR measurements were performed on a Nicolet iS50 FT-IR spectrometer. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AC-400 MHz spectrometer. Samples for electron microscopy were prepared by drying 10 μL of concentrated particle solution on silicon substrates (5 × 5 mm2 for SEM) or carbon-coated copper grids (TEM). Samples were air-dried overnight and imaged using JSM-7000F (SEM, 15.0 kV) or JEM 2000FXII (TEM, 200 kV).

Protein Adsorption Measurements:

Nonspecific adsorption of proteins was tested on MAGIC and MGNPs with various modifications for comparison. Therefore, nanoparticles (200 μL, 1 mg mL−1) were magnetically separated and redispersed in 200 μL PBS containing 45 mg mL−1 HSA or in undiluted serum. Samples were incubated for 1 h on a shaker. The supernatant was removed upon magnetic separation and particles were washed three times with 150 μL PBS. Then, 150 μL PBS containing 5% SDS were added and samples were incubated for 5 min at 25 °C. The supernatant was carefully removed upon magnetic separation and diluted with 350 μL PBS. Samples were evaluated regarding their protein content as triplicates using the BCA assay according to manufacturer’s instructions (Micro BCA Protein Assay, Fisher Scientific).

Antibody Conjugation to Magnetic Gold Nanoparticles with Idealized Coating Nanoparticles:

For signal comparison in LSPR measurements, two types of MAGIC NPs were prepared, one conjugated with half antibodies and the other with full antibodies. Half antibodies were produced by mixing full antibodies (1 mg mL−1, 50 μL) with TCEP (10 mM, 10 μL) in 1× PBS (340 μL). After 45 min incubation at 20 °C, TCEP-reacted antibodies were washed three times via centrifugation (14 000 g, 35 min) using a 3-kDa amicon filter. The half antibody concentration was then measured via absorbance (NanoDrop) and adjusted to 0.2 mg mL−1. In case of full antibodies, the concentration was adjusted to 0.1 mg mL−1. For antibody conjugation, MAGIC particles were prewashed with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer. EDC in DI water (0.5 m, 50 μL) was then added to 50 μL MAGIC solution to activate particles. After 2 min, 20 μL full antibody or half antibody solution was added to MAGIC NPs solution (100 μL), and the mixture was incubated at 20 °C for 1 h. The final antibody-MAGIC conjugates were washed five times in 1× PBS by applying external magnetic field. The number of conjugated antibodies was determined by measuring the fluorescence in the supernatant after MAGIC conjugation using dye-labeled antibodies. Estimated dimensions of antibodies were obtained from ref. [58] and three possible orientations of antibodies on nanoparticle surfaces were averaged.

Preparation of Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Chips:

The LSPR chip was prepared by immobilizing Au bipyramid nanoparticles on a glass substrate.[59] In brief, glass slides were piranha-cleaned and immersed (90 min) into 1% MPTMS in EtOH for thiol-activation. The activated glass slides were then immersed into 0.2× Au-bipyramid solution and incubated for 6 h at 20 °C. Following triple washes with DI water, the glass slides were treated with 0.1 mM N-methylmaleimides for 1 h to block remaining thiol groups. The final LSPR chip was prepared by incubating capture antibodies and BSA blocking on the substrate (2 h incubation and 1 h blocking at 20 °C).

Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensing of NuMA1:

Target molecules were captured on the LSPR chip (30 min incubation). After washing with 1× PBS, antibody-conjugated MAGIC NPs (5 μL) were added to the substrate, and magnetic force was applied for 2 min. Last, the chip was washed with 1× PBS. A custom-built spectrometer was used to acquire absorption spectra. The absorbance measurement condition was fixed as 200 ms × 20 accumulations with 50 times of boxcar averaging function smoothing. In case of NuMA1-spiked urine analysis, human urine samples were tenfold diluted with 1× PBS before subjection to LSPR chip to minimize nonspecific LSPR shift by matrix effect.

Statistical Method:

Student’s t-test (two-tailed, n ≥ 3) was used to evaluate statistical differences between MAGIC and other polymer-coated beads. p < 0.03 (*), p < 0.002 (**), p < 0.0002 (***), p < 0.0001 (****).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank T. Son for helpful discussion about spectra measurement using a custom-built spectrometer. This work was supported in part by US NIH Grants R01CA204019 (R.W.), R01CA237332 (R.W.), R21CA236561 (R.W., H.L.), R01CA229777 (H.L.), R21DA049577 (H.L.), U01CA233360 (H.L.), US DOD-W81XWH1910199 (H.L.), DOD-W81XWH1910194 (H.L.); MGH Scholar Fund (H.L.), Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) in Korea under the Fostering Global Talents for Innovative Growth Program (P0008746) supervised by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT). I.G. was supported through the German Research Foundation (grant no. 444077706).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The following disclosures are not related to the subject matter of this work. R.W. is a consultant to ModeRNA, Tarveda, Lumicell, Seer, Earli, Aikili Biosystems, and Accure Health. H.L. is a consultant to Exosome Diagnostics, Accure Health, and Aikili Biosystems. The rest of the authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Isabel Gessner, Center for Systems Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge St, CPZN 5206, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Jin-Ho Park, Center for Systems Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge St, CPZN 5206, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Hsing-Ying Lin, Institute of Biomedical Engineering National Tsing Hua University Hsinchu City 300, Taiwan.

Hakho Lee, Center for Systems Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge St, CPZN 5206, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Ralph Weissleder, Center for Systems Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge St, CPZN 5206, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Department of Systems Biology, Harvard Medical School, 200 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].Li P, Lee GH, Kim SY, Kwon SY, Kim HR, Park S, ACS Nano 2021, 75, 1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Anker JN, Hall WP, Lyandres O, Shah NC, Zhao J, Van Duyne RP, Nat. Mater 2008, 7, 442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Im H, Shao H, Park YI,Peterson VM, Castro CM, Weissleder R, Lee H, Nat. Biotechnol 2014, 32, 490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lee C, Lawrie B, Pooser R, Lee KG, Rockstuhl C, Tame M, Chem. Rev 2021, 121, 4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Park J, Im H, Hong S, Castro CM, Weissleder R, Lee H, ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bagheri E, Ansari L, Sameiyan E, Abnous K, Taghdisi SM, Ramezani M, Alibolandi M, Biosens. Bioelectron 2020, 153, 112054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chiu N-F, Chen C-C, Yang C-D, Kao Y-S, Wu W-R, Nanoscale Res. Lett 2018, 13, 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gessner I, Fries JWU, Brune V, Mathur S,J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Park YI, Im H, Weissleder R, Lee H, Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Weissleder R, Nahrendorf M, Pittet MJ, Nat. Mater 2014, 13, 125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Issadore D, Park YI, Shao H, Min C, Lee K, Liong M, Weissleder R, Lee H, Lab Chip 2014, 14, 2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Squires TM, Messinger RJ, Manalis SR, Nat. Biotechnol 2008, 26, 417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bertrand N, Grenier P, Mahmoudi M, Lima EM, Appel EA, Dormont F, Lim JM, Karnik R, Langer R, Farokhzad OC, Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Blume JE, Manning WC, Troiano G, Hornburg D, Figa M, Hesterberg L, Platt TL, Zhao X, Cuaresma RA, Everley PA, Ko M, Liou H, Mahoney M, Ferdosi S, Elgierari EM, Stolarczyk C, Tangeysh B, Xia H, Benz R, Siddiqui A, Carr SA, Ma P, Langer R, Farias V, Farokhzad OC, Nat. Commun 2020, 11, 3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Corbo C, Li AA, Poustchi H, Lee GY, Stacks S, Molinaro R, Ma P, Platt T, Behzadi S, Langer R, Farias V, Farokhzad OC, Adv. Healthcare Mater 2021, 10, e2000948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Perng W, Palui G, Wang W, Mattoussi H, Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sanchez-Cano C, Carril M, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2020, 21, 1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gessner A, Lieske A, Paulke B, Müller R, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2002, 54, 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ashraf S, Park J, Bichelberger MA, Kantner K, Hartmann R, Maffre P, Said AH, Feliu N, Lee J, Lee D, Nienhaus GU, Kim S, Parak WJ, Nanoscale 2016, 8, 17794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Peracchia MT, Harnisch S, Pinto-Alphandary H, Gulik A, Dedieu JC, Desmaële D, d’Angelo J, Müller RH, Couvreur P, Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li L, Chen S, Jiang S,J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed 2007, 18, 1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ostuni E, Chapman RG, Holmlin RE, Takayama S, Whitesides GM, Langmuir 2001, 17, 5605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].García KP, Zarschler K, Barbaro L, Barreto JA, O’Malley W, Spiccia L, Stephan H, Graham B, Small 2014, 10, 2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yang W, Zhang L, Wang S, White AD, Jiang S, Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Han Y, Yuan Z, Zhang P, Jiang S, Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 8561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Keefe AJ, Jiang S, Nat. Chem 2012, 4, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Andrés Vergés M, Costo R, Roca AG, Marco JF, Goya GF, Serna CJ, Morales MP, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys 2008, 41, 134003. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cai H, An X, Cui J, Li J, Wen S, Li K, Shen M, Zheng L, Zhang G, Shi X, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gessner I, Yu X, Jüngst C, Klimpel A, Wang L, Fischer T, Neundorf I, Schauss AC, Odenthal M, Mathur S, Sci. Rep 2019, 9, 2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Jiang S, Cao Z, Adv. Mater 2010, 22, 920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Vaisocherová H, Yang W, Zhang Z, Cao Z, Cheng G, Piliarik M, Homola J, Jiang S, Anal. Chem 2008, 80, 7894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Santoni G, Morelli MB, Amantini C, Battelli N, Front. Oncol 2018, 8, 362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cedervall T, Lynch I, Lindman S, Berggård T, Thulin E, Nilsson H, Dawson KA, Linse S, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2007, 104, 2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lacerda SH, Park JJ, Meuse C, Pristinski D, Becker ML, Karim A, Douglas JF, ACS Nano 2010, 4, 365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ke PC, Lin S, Parak WJ, Davis TP, Caruso F, ACS Nano 2017, 11, 11773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Liu Y, Wang J, Xiong Q, Hornburg D, Tao W, Farokhzad OC, Acc. Chem. Res 2021, 54, 291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Monopoli MP, Aberg C, Salvati A, Dawson KA, Nat. Nanotechnol 2012. 7, 779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tenzer S, Docter D, Kuharev J, Musyanovych A, Fetz V, Hecht R, Schlenk F, Fischer D, Kiouptsi K, Reinhardt C, Landfester K, Schild H, Maskos M, Knauer SK, Stauber RH, Nat. Nanotechnol 2013. 8, 772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Simon J, Kuhn G, Fichter M, Gehring S, Landfester K, Mailänder V, Cells 2021, 10, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Moore A, Weissleder R, Bogdanov A,J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1997, 7, 1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chen H, Wang L, Yeh J, Wu X, Cao Z, Wang YA, Zhang M, Yang L, Mao H, Biomaterials 2010, 31, 5397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gref R, Lück M, Quellec P, Marchand M, Dellacherie E, Harnisch S, Blunk T, Müller RH, Colloids Surf., B 2000, 18, 301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lundqvist M, Stigler J, Elia G, Lynch I, Cedervall T, Dawson KA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 14265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cao Z, Zhang L, Jiang S, Langmuir 2012, 28, 11625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chang Y, Chen S, Yu Q, Zhang Z, Bernards M, Jiang S, Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Shao Q, He Y, White AD, Jiang S, J. Chem. Phys 2012, 136, 225101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Russo MJ, Han M, Desroches PE, Manasa CS, Dennaoui J, Quigley AF, Kapsa RMI, Moulton SE, Guijt RM, Greene GW, Silva SM, ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Frutiger A, Tanno A, Hwu S, Tiefenauer RF, Vörös J, Nakatsuka N, Chem. Rev 2021, 121, 8095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lowe S, O’Brien-Simpson NM, Connal LA, Polym. Chem 2015, 6, 198. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cheng G, Li G, Xue H, Chen S, Bryers JD, Jiang S, Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Zhang Z, Chen S, Jiang S, Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zoppe JO, Ataman NC, Mocny P, Wang J, Moraes J, Klok HA, Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Mosayebi J, Kiyasatfar M, Laurent S, Adv. Healthcare Mater 2017, 6, 1700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Weissleder R, Stark DD, Engelstad BL, Bacon BR, Compton CC, White DL, Jacobs P, Lewis J, AJR, Am. J. Roentgenol 1989, 152, 167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Harisinghani MG, Barentsz J, Hahn PF, Deserno WM, Tabatabaei S, van de Kaa CH, de la Rosette J, Weissleder R, N. Engl. J. Med 2003, 348, 2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Goon IY, Lai LMH, Lim M, Munroe P, Gooding JJ, Amal R, Chem. Mater 2009, 21, 673. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hill HD, Mirkin CA, Nat. Protoc 2006, 1, 324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hampitak P, Melendrez D, Iliut M, Fresquet M, Parsons N, Spencer B, Jowitt TA, Vijayaraghavan A, Carbon 2020, 165, 317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Fang C, Zhao G, Xiao Y, Zhao J, Zhang Z, Geng B, Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 36706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.