Abstract

Lymphoid-specific helicase (LSH) is a member of the SNF2 helicase family of chromatin-remodelling proteins. Dysfunctions or mutations in LSH causes an autosomal recessive disease known as immunodeficiency-centromeric instability-facial anomaly (ICF) syndrome. Interestingly, LSH participates in various aspects of epigenetic regulation, including nucleosome remodelling, DNA methylation, histone modifications and heterochromatin formation. Further, LSH plays a crucial role during DNA-damage repair, specifically during double-strand break (DSB) repair, since murine LSH was shown to be essential for non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). Accordingly, overexpression of LSH drives tumorigenesis and malignancy. On the other hand, LSH homologs stabilise the genome. Thus, LSH might be implemented as a biomarker for various cancer types and potential target molecule to develop therapeutic strategies against them. In this review, we focus on the role of LSH in orchestrating chromatin rearrangements, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, as well as in DNA-damage repair. Changes in chromatin structure may facilitate gene expression signatures that cause malignant transformation. We summarise recent findings of LSH in cancers and raise critical open questions for further studies.

Subject terms: Oncogenes, Oncogenes

Background of LSH

Epigenetic mechanisms of transcriptional regulation involve DNA methylation, histone modifications, nucleosome positioning and heterochromatin formation [1], all of which contribute to establishing of specific gene expression signatures resulting in lineage-specific cell fates [2, 3]. Epigenetic changes of chromatin are heritable and reversible, being written, read and erased by a vast number of proteins belonging to different protein superfamilies, including ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes, which either move, eject or restructure nucleosomes. There are at least four families of chromatin remodelers in eukaryotes: SWI/SNF, ISWI, NuRD/Mi-2/CHD and INO80 [4]. Although all chromatin-remodelling complexes share a common ATPase domain, their functions are specific in the context of different biological processes. LSH belongs to the SNF2 helicase family from the helicase-like superfamily 2 (SF2). Within SF2, the SNF2 family refers to proteins with homologous sequence to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Snf2p. The SNF2 family consists of a large group of ATP-hydrolysing proteins, which are generally present in eukaryotes, as well as eubacteria and archaea [5]. They are ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers that facilitate the accessibility of DNA to transcription factors [6, 7]. Members of the SNF2 family share a common core of two recA-like domains, and link ATP hydrolysis to a change in the relative orientation of these domains [5].

The murine LSH homolog is also named PASG and SMARCA6 [8]. Jarvis et al. found that the Lsh gene is required for lymphocyte development and immunoglobulin class switch recombination [9]. A further study by Geiman et al. demonstrated that Lsh is required for normal murine development [10]. Moreover, Lsh is required for genome-wide methylation since its depletion led to genome-wide hypomethylation [11–13]. Interestingly, Lee et al. revealed that the levels of the human LSH homolog, named HELLS, were reduced after cytokine withdrawal in the human acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia cell line, MO7e, whereas HELLS levels were increased in highly proliferative tissues, indicating its association with cellular proliferation [8]. Interestingly, the impact of LSH on cellular proliferation is demonstrated in tumour progression, as failure to repress Lsh in retinoblastoma mouse models resulted in retinal tumorigenesis [14]. More recently, the function of LSH has broadened into DNA-damage response (DDR) regulation and carcinogenesis, which will be further discussed below. Considering that LSH acts as an upstream regulator in the network driving a tumorigenic phenotype, it might be considered a potential target for future therapies.

LSH is a key regulator of chromatin structure

Pluripotency of embryonic stem cells strongly relies on specific gene expression signatures which are partially determined by their chromatin structure [15, 16]. ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes are fundamental regulators of chromatin and gene expression, including members of the four families of chromatin remodelers: SWI/SNF, ISWI, NuRD/Mi-2/CHD and INO80. Complexes of the SWI/SNF family activate promoter/enhancer regions by epigenetic modulation of chromatin structure. LSH, a chromatin-remodelling protein of the SNF2 family, is primarily responsible for ATP-dependent nucleosome remodelling [17, 18]. In line with this idea, Ren et al. showed that Lsh is required for proper nucleosome density implementing nucleosome occupancy assays in wild-type (wt) and Lsh-deficient (Lsh−/−) embryonic stem (ES) cells [17]. In addition, by integrative analysis of RNA sequencing and micrococcal nuclease sequencing in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells, Law et al. revealed that overexpression of HELLS (gene coding for human LSH) increased nucleosome occupancy. This obstructed the accessibility of enhancers and hindered the formation of the nucleosome-free region at the transcription start sites. These events resulted in epigenetic silencing of multiple tumour suppressor genes and HCC progression [18].

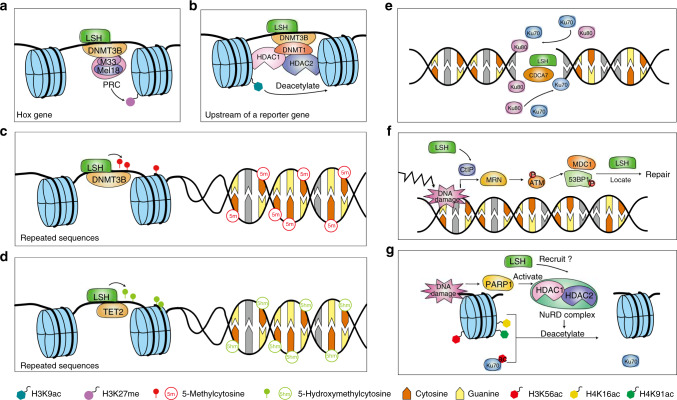

Furthermore, LSH is also involved in other mechanisms affecting chromatin structure, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications (Fig. 1). DNA methylation is the best-characterised DNA modification and occurs mainly at carbon 5 in the cytosine (5-methylcytosine, 5mC) of CpG dinucleotides in eukaryotes [19, 20]. Proper DNA methylation patterns are essential for cell differentiation and embryonic development. DNA methylation plays a critical role in gene repression and genome stability by preventing recombination events between repetitive sequences [20]. DNA methylation is mediated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), including DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B [21]. Interestingly, DNA methylation at repeat elements, a hallmark of heterochromatin, is significantly reduced in Lsh−/− ES cells [17]. Moreover, the ATP binding site of LSH is required for stable association of DNMT3B to repetitive elements, supporting that the nucleosome remodelling activity of LSH on chromatin is crucial for DNA methylation at repetitive elements and, consequently, for heterochromatin formation [17]. In addition, the methylation of satellite sequences requires CDCA7, which facilitates the recruitment of LSH onto chromatin [22]. According to these findings, fibroblasts derived from Lsh−/− mouse embryos, which lack DNA methylation from centromeric repeats, transposons and several genes’ promoters, are capable of reestablishing DNA methylation pattern after re-expression of Lsh, thereby demonstrating the causal involvement of LSH in methylation of repetitive elements and heterochromatin formation [23]. Further, Lsh is also required for methylation of transposable elements, mitosis and meiosis during cell division and gametogenesis, respectively, as demonstrated by defects detected in Lsh−/− mice during meiotic chromosome synapsis in female germ cells, centromere transcription during oocytes meiosis and meiotic progression in spermatocytes [24–27]. Interestingly, LSH has been shown to regulate long terminal repeats retrotransposon repression independent of DNMT3B [28]. Dunican et al. propose a model in which Lsh is required at a specific time window during development to target de novo methylation to repetitive sequences, which DNMT1 subsequently maintains to enforce selective silencing of the targeted repetitive sequences [28].

Fig. 1. LSH is a key regulator of chromatin structure and DNA-damage repair.

a LSH interacts with DNMT3B and PRC components to promote H3K27 methylation of Hox genes and therefore silences their expression during cell development. b LSH recruits DNMT3B, DNMT1, HDAC1 and HDAC2 to deacetylate H3K9ac, acting as a histone transcriptional repressor. c LSH participates in the methylation of repetitive sequences, which are essential components of heterochromatin. LSH helps DNMT3B locate to DNA and methylate centromeric repeats, transposons and gene promoters rich with CpG sites. d LSH upregulates TET2 and forms a complex with it to maintain the genomic 5-hmC level. In response to DNA-damage, mammalian cells initiate DDR and downstream pathways. For DSB, there are two major pathways to repair the damage, NHEJ and HR. Besides, two minor pathways, rd-NHEJ and MMEJ, can ligate ends. As a member of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeler family, LSH helps to remodel chromatin and facilitates repairing molecules that binds to damaged sites. e LSH and CDCA7 participate in C-NHEJ, in which they recruit protein Ku70 and Ku80 to the damaged sites for afterwards repairing. f In HR, after DNA damage, MRN and ATM are activated, impacting various substrates. LSH recruits MDC1 and 53BP1 protein to targeted sites, facilitating the repairing process. g In MMEJ, HDAC1 and HDAC2 participate in DNA repair by deacetylating H3K56, H4K16 and H4K91, as well as Ku70. Considering that LSH cooperates with HDAC1 and HDAC2 in epigenetic modulation of histone, there exists a possibility that LSH recruits HDAC1 and HDAC2 in response to DNA damage.

DNA methylation can be reverted back via active DNA demethylation, which consists of a series of oxidation steps converting 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC). The latter two are eventually excised by thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG), followed by base-excision repair (BER) to restore the cytosine [29, 30]. Conversion of 5mC to 5-hmC by ten-eleven translocation (TET) family enzymes plays an essential biological role in embryonic stem cells, development, ageing and disease [31]. Interestingly, LSH has been shown to interact with TET2 and participates in the conversion of 5mC to 5-hmC specifically at heterochromatin-associated satellite DNA loci [32]. Moreover, LSH promoted genome stability by silencing satellite expression, affecting 5-hmC levels in pericentromeric satellite repeats. Decreased levels of LSH in specific cancer types are one of the mechanisms underlying 5-hmC reduction, genome instability and metastasis [32]. Due to the function of TETs as mediators of active DNA demethylation [31], the interaction between TET2 and LSH seems to be paradoxical at first instance. However, previous studies indicated that loss of TET is partially associated with genome hypomethylation, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B facilitate DNA demethylation at low concentrations of the methyl group donor, S-adenosyl methionine [33]. Thus, elucidating the unconventional roles of TETs and DNMTs, and how LSH impacts DNA methylation in cooperation with TETs and DNMTs remains on the scope.

Besides DNA methylation, LSH is also involved in histone modifications. While DNA methylation is a relatively stable change in somatic cells, post-translational modifications of histone proteins are more diverse and complex, and can change rapidly during the cell cycle [19]. Histone proteins are part of nucleosomes, which are the structural and functional units of chromatin. Histone proteins can undergo post-translational modifications at their N-terminal tails, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination and sumoylation, among others [34–36]. Specific combinations of histone modifications called the "histone code" imparts the expression status of a region of the chromatin [34]. It seems that Lsh is required for normal histone methylation, since in Lsh−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) the reduction of DNA methylation is associated with de novo monomethylation of the core histone 3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me1) [37]. Interestingly, Yu et al. showed a functional correlation between H3K4me1 enrichment at genomic sites with reduced DNA methylation, enhancer formation and cellular plasticity by characterising induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells from wt and Lsh−/− MEFs [37]. Moreover, Lsh knockout results in accumulation of di- and tri-methylated histone 3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me2 and H3K4me3) at repetitive sequences, including pericentromeric DNA [12], whereas di- or tri-methylation of H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9me2 and H3K9me3) appear unchanged after Lsh deletion [12]. On the other hand, LSH gain-of-function (GOF) increases the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 and decreases the active histone mark H3K4me3, supporting that LSH mediates gene repression upon binding to promoters [18, 38]. Interestingly, LSH-mediated histone methylation seems essential for cellular plasticity and differentiation of ES cells or MEFs under conditions favouring specific lineage differentiation [37, 39]. Ren et al. showed that the association of LSH to the Oct4 promoter during differentiation of ES cells mediates transcriptional repression, which is accompanied by less chromatin accessibility, an increase of repressive histone marks and gain of DNA methylation at distal and proximal Oct4 enhancer sites [38]. Following this line of ideas, Xi et al. demonstrated that LSH associates to some Hox genes during embryonic development and mediates their silencing by regulating DNMT3B binding, DNA methylation and specific repressive histone modifications, the last ones through the interaction with components of the polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) [40–42].

Along with methylation of histones, LSH also facilitates deacetylation of histones. LSH cooperates with DNMT1, DNMT3B and the histone deacetylases (HDACs) HDAC1 and HDAC2 to reduce acetylation levels of H3 and H4 and to silence transcription [43]. For instance, when this complex is targeted to GAL4-binding sites upstream of a reporter gene promoter, it represses gene expression by deacetylating H3K9ac and H4K12ac [43]. Myant and Stancheva proposed that LSH serves as a recruiting factor for DNMTs and HDACs to establish transcriptionally repressive chromatin that is further stabilised by DNA methylation at specific loci [43].

In conclusion, LSH is involved in various aspects of epigenetic gene silencing, including chromatin remodelling, DNA methylation and histone modifications, which in turn are crucial for different biological processes, such as pluripotency, somatic cell reprogramming, embryonic development, cell differentiation, as well as pathological processes including malignant transformation and tumour progression, among others.

LSH acts as a modulator of DNA repair

DNA damage is usually caused by exposure to genotoxic agents and physiological DNA transitions. Single-strand DNA (ssDNA) breaks are DNA lesions typically resulting from oxidative damage or base hydrolysis. ssDNA breaks lead to substitutions or even DSB. Other situations, such as depurination, depyrimidination and 8-oxoG, occur frequently and determine the standard organisation of DNA [44, 45]. DSB, one of the most severe lesions, arises from ionising radiation, reactive oxygen species, DNA replication errors and inadvertent cleavage by nuclear enzymes [46]. Further, DSB shows a high incidence at repetitive DNA, non-B DNA structures, DNA–protein barriers and highly transcribed regions [46].

To preserve genomic integrity, eukaryotic cells develop DDR. In response to DSB, DDR initiates two downstream pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) [47, 48]. NHEJ restores DNA integrity in an error-prone way since it could ligate two ends without any deletion or addition from either strand. As for HR, a homologous DNA molecule is requested as a template; therefore, HR is generally error-free and activated during S and G2 phases [49]. Although LSH does not repair DNA damages directly, recent studies depicted LSH as a positive modulator in DSB repair, both in canonical NHEJ (C-NHEJ) and HR, unveiling its impacts on genomic homoeostasis and cancer biology (Fig. 1) [45].

C-NHEJ is initiated by protein Ku80 (XRCC5 or Ku86) and Ku70 (XRCC6), which bind to DSB ends and recruit DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit [50, 51]. Once started, DNA ligase IV complex, including DNA-dependent protein kinase, ligase IV, X-ray repair cross-complementing gene 4 (XRCC4) and XRCC4-like factor will ligate ends and multiple substrates will be phosphorylated to complete the repairing [50]. In C-NHEJ, LSH helps to recruit Ku80 and Ku70 to DSB sites. Dysfunction of LSH protein leads to ICF type 4, while mutations in DNMT3B, ZBTB24 and CDCA7 genes are responsible for ICF types 1, 2 and 3. All four ICF types show phenotypic similarities, including DNA hypomethylation and immune deficiencies [45]. The function of LSH, DNMT3B, ZBTB24 and CDCA7 is correlated with each other. Whereas ZBTB24 enhances the transcription of the CDCA7 gene, the CDCA7 protein promotes the assembly of LSH onto chromatin. Further, LSH recruits DNMT3B and DNMT3B mediates DNA methylation [22]. Malfunction of any protein of the ZBTB24-CDCA7-LSH-DNMT3B axis leads to DNA methylation defects and vulnerability to DNA damage. Mutations in ICF-related genes, including ZBTB24, CDCA7, LSH and DNMT3B, affect cellular DNA-repair ability, and therefore, increase the levels of the DNA-damage marker γH2AX, particularly in the centromeric, pericentromeric, and telomeric regions [45]. Interestingly, a recent study found that the C-NHEJ pathway was altered in Lsh-deficient B cells in a Ku70/80 independent manner, indicating that LSH might participate in C-NHEJ by different mechanisms [52].

In addition to C-NHEJ, LSH participates in HR [53]. In response to DSB damage, HR is embarked with break recognition and end-resection of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex in association with CtIP [54, 55]. Next, MRN interacts with ataxia–telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase or directly activates ATM, as they both assemble at the DSB sites [56]. Along this cascade, many effectors are activated. For example, after being activated by ATM, the mediator of DNA-damage checkpoint 1 (MDC1) recruits ATM to DSB sites, promoting the process [57]. Afterwards, with the phosphorylation at threonine 68 (T68) by ATM and MDC1, DDR checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) is activated and arrests the cell cycle [58]. Furthermore, P53-binding protein 1 (53BP1), a dispensable player in the HR process, is dephosphorylated via a BRCA1-dependent mechanism, contributing to HR by relaxing densely packed heterochromatin [59]. In this network, LSH recruits MDC1 and 53BP1 to the damage sites and facilitates the HR process of heterochromatin by facilitating end-resection and accumulation of CtIP at IR-induced foci [53, 60]. In the aspect of DSB induced within heterochromatin, downregulation of LSH results in fewer ssDNA foci, which partially overlaps with the defect in CtIP-depleted cells, indicating that LSH facilitates efficient repair of breaks [53]. In addition, LSH helps to open chromatins before meiosis. It is recruited by PRDM9 to HR hot spots, where most recombination occurs, and facilitates histone modifications enhancing chromatin accessibility [61].

Apart from Ku80, Ku70, MDC1, 53BP1 and CtIP, other proteins associated with LSH and DSB repair pathways have been suggested. Resection-dependent NHEJ (rd-NHEJ) and microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) are two alternative DSB repair pathways that act independently from Ku70/80 [54]. In MMEJ, the NuRD complex is recruited to rebuild the normal DNA structure [62]. In the NuRD complex, HDAC1 and HDAC2 promote DSB repair by deacetylating H3K56ac, H4K16ac and H4K91ac [63–65]. Also, HDAC1 and HDAC2 deacetylate Ku70 [66]. Inhibition of HDAC1 and HDAC2 in prostate cancer cells resulted in increased levels of Ku70 acetylation decreased Ku70 binding to DSB sites, and hypersensitivity to DSB induced by chemotherapy [66]. Though no direct evidence shows that LSH recruits HDAC1 and HDAC2 to the damage sites, a substantial probability of LSH-mediated recruitment of HDAC1 and HDAC2 to DNA exists.

To sum up, despite no direct function on DNA repair, LSH plays a significant role as a mediator of DNA-damage repair by recruiting other proteins, particularly during DSB. From this perspective, LSH handles the proper assembly of repairing proteins, cell-cycle controlling proteins, and possibly recruits HDACs to DSB sites to maintain genomic stability. However, since most experiments were conducted in mouse cells, further validation of the presence of the same molecular mechanisms in human cells remains essential.

LSH is a bridge regulator in oncogenesis

The increase of LSH protein and mRNA has recently emerged as a hallmark in many cancer types (Fig. 2). Clinical data extracted from the TCGA database demonstrated that elevated LSH mRNA levels negatively correlate with patients' overall survival in several kinds of cancers, including breast cancer, oesophageal adenocarcinoma, non-small-cell lung cancer and ovarian cancer (Fig. 2). Whereas in other cases, the aberrant levels of LSH mRNA could be a protective factor (Fig. 2) [67–69]. In non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), a component of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons derived from smoke and air pollution, recruits the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) to the promoter of the LSH gene and upregulates the levels of the LSH protein [70]. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the specificity protein 1 (SP1) elevates the expression of LSH by binding the upstream TSS [18]. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, the mRNA levels of LSH positively correlate with the transcription of the critical oncoprotein, forkhead box M1 (FOXM1) [69]. Degradation of LSH is suppressed in these cancer subtypes since its interaction with ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L3 (UCHL3), a member of the deubiquitinating enzyme family, is interfered by the lncRNA GIAT4RA [71]. In addition, high levels of LSH correlates with a poor prognosis in gastric cancer [72]. The mechanism associated with this observation might act through reduced levels of miR-365a-3p, since this microRNA binds to its 3' untranslated region (UTR) of the HELLS transcript and represses its translation, thereby resulting in reduced LSH levels and enhanced carcinogenesis [73].

Fig. 2. The expression of LSH in various cancers.

Data analysed in this figure were extracted from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). The overall survival rate graph of NSCLC is from the study conducted by Mao et al., and the usage of the graph was approved (PMID: 30094095) [95]. a LSH is overexpressed in many types of cancers. Here displays mRNA level in several kinds of cancers with the statistical difference (P < 0.05) between cancerous samples and normal ones. Information on LSH mRNA expression is from TCGA. To conduct the overall analysis, we filtered data with restriction, including transcriptome profiling of data category, gene expression qualification of data type, RNA-seq of experimental strategy and HTSeq-FPKM of workflow type. The nine presented graphs and the related projects are (bladder cancer: TCGA-BLCA), (breast cancer: TCGA-BRCA), (oesophageal carcinoma: TCGA-ESCA), (kidney cancer: TCGA-KIRC, TCGA-KIRP and TCGA-KICH), (liver cancer: TCGA-LIHC), (lung cancer: TCGA-LUAD and TCGA-LUSC), (thyroid carcinoma: TCGA-THCA) and (uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma: TCGA-UCEC). The gene expression levels were computed in an unpaired t-test using GraphPad Prism (v8.0.2). b The survival time correlates with the expression level of LSH. There is a correlation between patients’ survival time and the mRNA level of LSH. The elevated level of LSH mRNA could be a risk factor in breast cancer, oesophageal carcinoma, NSCLC and ovarian cancer. In contrast, high level of LSH mRNA might be a protective factor in head-neck squamous cell carcinoma, liver hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Data were respectively extracted: breast cancer from TCGA-BRCA, oesophageal carcinoma from TCGA-ESCA, NSCLC from the study conducted by Mao et al. [95], ovarian cancer from TCGA-OV, head-neck squamous cell carcinoma from TCGA-HNSC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma from TCGA- LIHC, pancreatic adenocarcinoma from TCGA-PAAD, and pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma from TCGA-PCPG. Overall survival Kaplan–Meier estimate was completed based on public TCGA data with GraphPad Prism (v8.0.2) and default settings. The outcomes demonstrate that the correlation can be positive or negative, depending on types of cancers. Only curves with P < 0.05 are displayed.

At the network level, LSH interacts with various modulators in different pathways, resulting in a more aggressive phenotype of tumour cells (Fig. 3). LSH controls the fate of tumour cells by its interaction with TP53 [70, 71, 74]. In nasopharyngeal cancer cells (NPCs), including HK1 and CNE1, there are at least three different mechanisms for LSH to induce activation of TP53, (i) by removing K11-linked and K48-linked polyubiquitin chain type in TP53; (ii) by interfering in the interaction between TP53 and MDM2 (a critical ubiquitin ligase of TP53); or (iii) by directly binding TP53 to activate TP53-mediated lipid catabolism, which in succession induces the expression of genes such as carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1B and 1C (CPT1B and CPT1C) [71]. Besides being a positive regulator of TP53, the cooperation between LSH and TP53 is potentially more refined. For instance, in cell lines derived from human lungs, LSH epigenetically silences the expression of P53RRA, a tumour suppressor gene that acts as an upstream activator of TP53 and is involved in cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis and ferroptosis [70]. As discussed above, the precise impact of LSH on TP53 can be exerted by multiple mechanisms. Therefore, the conventional view concerning the balance between survival and death of tumour cells should be reconsidered.

Fig. 3. The roles of LSH in carcinogenesis.

LSH is elevated in many cancers, which results from the increase of oncogenic factors and the interference with its ubiquitination. AhR binds to the Lsh gene promotor, and SP1 assembles at the upstream of the TSS, elevating the levels of LSH. Besides, there is a positive correlation between FOXM1 and LSH mRNAs. The lncRNA GIAT4RA impedes LSH binding with UCHL3, therefore hinders the ubiquitination of LSH. Increased LSH impacts metabolism, progress and even the fate of cancerous cells. LSH upregulates GLUTs and FADSs, activates TP53 protein and curbs FH. As a consequence, it promotes the Warburg effect, engages in TP53-related lipid catabolism, promotes TP53-related proline catabolism, and suppresses TCA, which motivates IKKα to switch binding sites and consequently, to promote EMT. Increased levels of LSH increase the levels of oncogenic proteins, including GINS4, E2F3 and CENPF, preserving the aggressive phenotype. Also, it inhibits ferroptosis by increasing the levels of the lncRNA LINC00336 and decreasing P53RRA mRNA. The lncRNA LINC00336 stabilises CBS, enhancing cell resistance to ferroptosis. The decline of P53RRA mRNA downregulates Fe2+ and ROS, and as a result, inhibits ferroptosis. However, the relationship between TP53 and LSH needs a cleared elucidation since P53RRA mRNA upregulates TP53 in an upstream manner. In summary, the anomalous expression of LSH accelerates carcinogenesis and leads to worse clinical outcomes.

In the regulation of metabolic pathways, the overexpression of Lsh inhibits ferroptosis, contributes to the Warburg effect, and promotes proline catabolism [70, 75, 76]. Concerning ferroptosis, LSH inhibits the expression of P53RRA [70], consequently decreasing two significant ferroptosis hallmarks, namely intracellular concentrations of Fe2+ and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [77]. LSH inhibits ferroptosis by increasing the expression of the lncRNA LINC00336 to preserve cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) levels, which fosters erastin-induced ferroptosis resistance [78]. Regarding the Warburg effect, apart from indirect effects via TP53, LSH promotes the expression of glucose transporters (GLUT), including GLUT1, GLUT6, GLUT12 and GLUT13, as well as the expression of fatty acid desaturases (FADS) including FADS2 and FADS5, which is consistent with the involvement of LSH in the expression of metabolism-related genes as well as boosting the Warburg effect [75]. Moreover, the recruitment of LSH and the euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 2 (EHMT2), also known as G9a [79], to fumarate hydratase (FH) promoters represses its expression. Further, it leads to increased TCA intermediates, such as α-KG and citrate, which prompt the inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase alpha (IKKα) to bind to the promoters of vimentin (VIM) and impair its binding to zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and E-cadherin, producing malignant progression [80]. As for proline catabolism, in NSCLC LSH facilitates TP53 binding to the promoter of proline dehydrogenase (PRODH) and elevates the levels of PRODH, which next fosters the expression of inflammatory cytokines including CXC11, LCN2 and IL17C [76].

Ectopic expression of Lsh promotes tumour growth. In HCC, LSH increases the levels of centromere protein F by binding to the transcription start site of its gene (CENPF), which positively correlates with tumour growth of xenografts in mice [67]. In colon cancer cells, LSH interacts with E2F transcription factor 3 (E2F3) in vivo and cooperates with its oncogenic functions [81]. Von Eys et al. identified genome-wide common target genes of LSH and E2F3 by chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by DNA sequencing [81]. Moreover, LSH binds and co-regulates promoters of active E2F3-target genes, including the trithorax-related MLL1. Besides, increased levels of LSH may promote epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) [68]. In NSCLCs, the overexpression of Lsh boosts GINS4 expression, which decreases the epithelial marker E-cadherin (CDH1) and increases the mesenchymal markers VIM and SNAI1 [68, 75]. It is suggested that LSH directly interacts with the 3' UTR of the GINS4 mRNA, as confirmed by RNA immunoprecipitation assays [68].

However, in metastatic cancer cells, a modest decline of LSH has been observed [32]. Comparing healthy human tissues, non-metastatic and metastatic tissues of NPC, colon and breast cancers, the protein levels of LSH and TET are statistically lowest in metastatic cancer tissues. Since TET converts 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hmC, and LSH acts as a 5-hmC reader in mouse embryonic stem cells [82, 83], it would not be surprising to observe a relative decline of 5-hmC in metastatic cancer tissues in comparison to non-metastatic ones. Moreover, the decline of 5-hmC correlates to genomic instability, which may explain the mild reduction of LSH in metastatic tissues [32].

In summary, the levels of LSH are elevated in many cancer types. More importantly, the vast amount of evidence indicates that LSH acts as a driver of malignant progression of tumour cells via its interaction with lncRNAs, oncoproteins or tumour suppressors, its primary control of transcriptional activity as a modulator of DNA methylation or its direct binding with post-translationally modified proteins [84], consequently promote metabolic changes, EMT and tumour growth, as well as ferroptosis inhibition. However, a previous article reported a decrease in the expression of Lsh in metastatic cancers compared with non-metastatic ones and healthy tissues, which evidences the need for further studies and more robust statistics to validate this finding [32]. Nevertheless, the increase of LSH is still tightly linked with poor clinical outcomes and is emerging as a novel prognostic marker [85].

Homologs of LSH

There are multiple helicase homologs of the SWI2/SNF2 family (Fig. 4). The most representative one is the protein decreases in DNA methylation 1 (DDM1) in plants. In alignment with LSH function, DDM1 controls DNA methylation [86]. DDM1 mainly contributes to the cytosine methylation of DNA, including CpG, CHG (H = A, C or T), and CHH sequences in plants [74, 87]. Knockout of DDM1 not only results in immediate hypomethylation at regions marked by H3K9me2 but also leads to heritable epialleles in self-pollinated lines. For instance, the progressive loss of DNA methylation at differentially methylated regions with lower H3K9me2 marks at the flowering Wageningen (FWA) locus induces inheritable changes in late-flowering phenotype [88, 89]. During heterochromatin formation, the Arabidopsis nucleosome remodeler DDM1 facilitates the access of DNA methyltransferase DRM2 to H1-containing chromatin [90, 91]. As a result, DDM1 inhibits small RNA-directed DNA methylation by suppressing the expression of small RNAs [87, 92]. Besides, DDM1 may control pressure responses via transposable elements and stress-related long intergenic noncoding RNAs [93].

Fig. 4. Domains of LSH homologs.

Five homologs from animals, plants and fungi are depicted above. Protein names and species are listed at the left. Conserved domains are labelled. SNF-rel refers to SNF2 related domain; Helicase_C refers to Helicase conserved C-terminal domain.

In fungi, the LSH homolog induces different effects when compared to the mammalian or botanical ones. The Neurospora homolog mutagen sensitive-30 (MUS-30) contains an N-terminal SNF2 DEAD-box helicase domain and a C-terminal HelicC domain. In contrast with LSH or DDM1, MUS-30 exhibits no influence on DNA methylation or meiosis. However, a study verified that this kind of LSH/DDM1 homolog is essential during DNA damage. In detail, knockout of MUS-30 results in hypersensitivity to methyl methanesulfonate, and replication forks may collapse, resulting in double-strand breaks (DSB). Moreover, MUS-30 is necessary for toxic base-excision repair instead of general HR or NHEJ pathways [51].

The increased recombination centres 5 (IRC5) protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a member of the conserved SNF2 family of ATP-dependent DNA translocases. Similarly, IRC5 plays a role in resistance to DNA damage. Epistasis analysis showed that the impaired expression of IRC5 disrupts the interaction between checkpoint activators of DNA damage and genes involved in DNA-damage tolerance. Furthermore, ICR5 is essential for cohesin binding to centromeres and chromosome arms. ICR5 interacts with genes that encode proteins mediating the replication fork stability and sister chromatid cohesion (SCC). Mutation of Irc5 leads to reduced SCC1 protein levels and impaired interaction between SCC1 and SCC2 proteins, consequently decreasing the levels of cohesin, causing separation of premature sister chromatid. Moreover, the mutant Irc5 contributes to the loss of rDNA repeats, undermining the cellular homoeostasis [94].

Overall, LSH and its homologs are guardians of genomic stability and protectors of the DNA structure. A similar contribution to DNA methylation by LSH and DDM1 may reveal a conserved mechanism between plants and mammals and could provide a distinctive insight into the functions of LSH [86, 93]. However, higher molecular diversity is present in fungi since MUS-30 and IRC50, the homologs of LSH, mainly monitor the structure of DNA and take part in chromatin structure but have shown little impact on DNA methylation [51, 94].

Concluding remarks

LSH, along with its homologs, facilitates heterochromatin formation, epigenetic silencing of target genes and DNA-damage repair. A better characterisation of the roles of LSH in the mechanisms modulating chromatin structure, differentiation of stem cells and oncogenesis will be fundamental for further studies. More research is expected to reveal the detailed mechanisms of the interaction between LSH and the DNA methyltransferase DNMT3B and the DNA demethylating TET proteins. Besides, the general interest in the role of LSH in tumour cells has broadened. Apart from epigenetic modulations, LSH is substantially involved in the metabolism of tumour cells. Multilayered interactions between LSH and TP53 and TP53-relevant lipid catabolism demand more experiments to elucidate the exact role of LSH in metabolism [71]. Associated with the Warburg effect, ferroptosis and proline catabolism, LSH emerges as a potential target to suppress cancers' malignant progression. As indicated by recent studies, ectopics level of LSH may result in severe clinical outcomes [18]; on the contrary, the knockdown of LSH suppresses the migration of tumour cells [80]. Suppressors of LSH may be promising for clinical applications against the malignant progression of cancers, though more investigations are required to portray how LSH mediates metabolism and immunity and whether targeting LSH is a beneficial choice.

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members of the laboratory for their resourceful comments on the manuscript.

Author contributions

YT, DX and GB contributed to the conception of the study; XC, Yamei Li and KR wrote the manuscript; BD, Yuyi Li and QT performed the data analyses; CM and SL helped with constructive discussions.

Funding information

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [82072594, 81672787, YT; 82073097, 81874139, 81672991, S.Liu; 82002916, CM; 82073136, 81772927, DX], China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [2019 M652804, CM], Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province [2020JJ5790, CM], Hunan Provincial Key Area R&D Programs [2019SK2253, YT], Postdoctoral Foundation of Central South University [220372, CM], Shenzhen Science and Technology Program [KQTD20170810160226082, YT], and Shenzhen Municipal Government of China [JCYJ20180507184647104, YT]. Guillermo Barreto was funded by the “Université Paris-Est Créteil” (UPEC, Créteil, France), the “Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique” (CNRS, France), “Délégation Centre-Est” (CNRS-DR6), the “Lorraine Université” (LU, France) through the initiative “Lorraine Université d’Excellence” (LUE) and the dispositive “Future Leader” and the “Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft” (DFG, Bonn, Germany) (BA 4036/4-1). Karla Rubio was funded by the “Consejo de Ciencia y Tecnología del Estado de Puebla” (CONCYTEP, Puebla, Mexico) through the initiative International Laboratory EPIGEN.

Data availability

Data analysed in Fig. 2 were extracted from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). The overall survival rate graph of NSCLC is from the study conducted by Mao et al., and the usage of the graph was approved (PMID: 30094095).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work does not require any ethical approval or participating consent.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. This manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, and has not been submitted to or is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Desheng Xiao, Email: xdsh96@csu.edu.cn.

Guillermo Barreto, Email: Guillermo.barreto@univ-lorraine.fr.

Yongguang Tao, Email: taoyong@csu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-021-01543-2.

References

- 1.Cavalli G, Heard E. Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature. 2019;571:489–99. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boland M, Nazor K, Loring J. Epigenetic regulation of pluripotency and differentiation. Circulation Res. 2014;115:311–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.301517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobersch, S, Rubio, K, Barreto, G. Pioneer factors and architectural proteins mediating embryonic expression signatures in cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2019. 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Singh AK, Mueller-Planitz F. Nucleosome positioning and spacing: from mechanism to function. J Mol Biol. 2021;433:166847. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flaus A, Martin D, Barton G, Owen-Hughes T. Identification of multiple distinct Snf2 subfamilies with conserved structural motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2887–905. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartholomew B. Regulating the chromatin landscape: structural and mechanistic perspectives. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83:671–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051810-093157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozturk N, Singh I, Mehta A, Braun T, Barreto G. HMGA proteins as modulators of chromatin structure during transcriptional activation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2014;2:5. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2014.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee DW, Zhang K, Ning ZQ, Raabe EH, Tintner S, Wieland R, et al. Proliferation-associated SNF2-like gene (PASG): a SNF2 family member altered in leukemia. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3612–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvis CD, Geiman T, Vila-Storm MP, Osipovich O, Akella U, Candeias S, et al. A novel putative helicase produced in early murine lymphocytes. Gene. 1996;169:203–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geiman T, Tessarollo L, Anver M, Kopp J, Ward J, Muegge K. Lsh, a SNF2 family member, is required for normal murine development. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2001;1526:211–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dennis K, Fan T, Geiman T, Yan Q, Muegge K. Lsh, a member of the SNF2 family, is required for genome-wide methylation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2940–4. doi: 10.1101/gad.929101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan Q, Huang J, Fan T, Zhu H, Muegge K. Lsh, a modulator of CpG methylation, is crucial for normal histone methylation. EMBO J. 2003;22:5154–62. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muegge K, Geiman T, Xi S, Jiang Q, Schmidtman A, Chen T, et al. Lsh is involved in de novo methylation of DNA. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res Annu Meet. 2006;47:541–541. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zocchi L, Mehta A, Wu SC, Wu J, Gu Y, Wang J, et al. Chromatin remodeling protein HELLS is critical for retinoblastoma tumor initiation and progression. Oncogenesis. 2020;9:25. doi: 10.1038/s41389-020-0210-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sha K, Boyer LA. The chromatin signature of pluripotent cells (May 31, 2009), StemBook, ed. The Stem Cell Research Community, StemBook, 10.3824/stembook.1.45.1, http://www.stembook.org.

- 16.Delgado-Olguin P, Recillas-Targa F. Chromatin structure of pluripotent stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. Brief Funct Genomics. 2011;10:37–49. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elq038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren J, Briones V, Barbour S, Yu W, Han Y, Terashima M, et al. The ATP binding site of the chromatin remodeling homolog Lsh is required for nucleosome density and de novo DNA methylation at repeat sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:1444–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Law C-T, Wei L, Tsang FH-C, Chan CY-K, Xu IM-J, Lai RK-H, et al. HELLS regulates chromatin remodeling and epigenetic silencing of multiple tumor suppressor genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2019;69:2013–30. doi: 10.1002/hep.30414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deaton AM, Bird A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1010–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.2037511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta A, Dobersch S, Romero-Olmedo AJ, Barreto G. Epigenetics in lung cancer diagnosis and therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015. 10.1007/s10555-015-9563-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Smith Z, Meissner A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:204–20. doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenness C, Giunta S, Müller MM, Kimura H, Muir TW, Funabiki H. HELLS and CDCA7 comprise a bipartite nucleosome remodeling complex defective in ICF syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E876–e885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717509115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Termanis A, Torrea N, Culley J, Kerr A, Ramsahoye B, Stancheva I. The SNF2 family ATPase LSH promotes cell-autonomous de novo DNA methylation in somatic cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:7592–604. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De La Fuente R, Baumann C, Fan T, Schmidtmann A, Dobrinski I, Muegge K. Lsh is required for meiotic chromosome synapsis and retrotransposon silencing in female germ cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1448–54. doi: 10.1038/ncb1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng W, Baumann C, Schmidtmann A, Honaramooz A, Tang L, Bondareva A, et al. Lymphoid-specific helicase (HELLS) is essential for meiotic progression in mouse spermatocytes. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:1235–41. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.085720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan T, Yan Q, Huang J, Austin S, Cho E, Ferris D, et al. Lsh-deficient murine embryonal fibroblasts show reduced proliferation with signs of abnormal mitosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4677–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumann C, Ma W, Wang X, Kandasamy MK, Viveiros MM, De La Fuente R. Helicase LSH/Hells regulates kinetochore function, histone H3/Thr3 phosphorylation and centromere transcription during oocyte meiosis. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4486–4486. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18009-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunican DS, Cruickshanks HA, Suzuki M, Semple CA, Davey T, Arceci RJ, et al. Lsh regulates LTR retrotransposon repression independently of Dnmt3b function. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R146. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-12-r146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barreto G, Schafer A, Marhold J, Stach D, Swaminathan SK, Handa V, et al. Gadd45a promotes epigenetic gene activation by repair-mediated DNA demethylation. Nature. 2007;445:671–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu X, Zhang Y. TET-mediated active DNA demethylation: mechanism, function and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18:517–34. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2017.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross SE, Bogdanovic O. TET enzymes, DNA demethylation and pluripotency. Biochem Soc Trans. 2019;47:875–85. doi: 10.1042/BST20180606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia J, Shi Y, Chen L, Lai W, Yan B, Jiang Y, et al. Decrease in lymphoid specific helicase and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is associated with metastasis and genome instability. Theranostics. 2017;7:3920–32. doi: 10.7150/thno.21389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Wijst M, Venkiteswaran M, Chen H, Xu G, Plösch T, Rots M. Local chromatin microenvironment determines DNMT activity: from DNA methyltransferase to DNA demethylase or DNA dehydroxymethylase. Epigenetics. 2015;10:671–6. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1062204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Fischle W, Cheung W, Jacobs S, Khorasanizadeh S, Allis CD. Beyond the double helix: writing and reading the histone code. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;259:3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh I, Ozturk N, Cordero J, Mehta A, Hasan D, Cosentino C, et al. High mobility group protein-mediated transcription requires DNA damage marker gamma-H2AX. Cell Res. 2015;25:837–50. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobersch S, Rubio K, Singh I, Gunther S, Graumann J, Cordero J, et al. Positioning of nucleosomes containing gamma-H2AX precedes active DNA demethylation and transcription initiation. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1072. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu W, Briones V, Lister R, McIntosh C, Han Y, Lee EY, et al. CG hypomethylation in Lsh-/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts is associated with de novo H3K4me1 formation and altered cellular plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5890–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320945111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren J, Hathaway NA, Crabtree GR, Muegge K. Tethering of Lsh at the Oct4 locus promotes gene repression associated with epigenetic changes. Epigenetics. 2018;13:173–81. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2017.1338234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han Y, Ren J, Lee E, Xu X, Yu W, Muegge K. Lsh/HELLS regulates self-renewal/proliferation of neural stem/progenitor cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1136. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00804-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sparmann A, van Lohuizen M. Polycomb silencers control cell fate, development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:846–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viré E, Brenner C, Deplus R, Blanchon L, Fraga M, Didelot C, et al. The Polycomb group protein EZH2 directly controls DNA methylation. Nature. 2006;439:871–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh I, Contreras A, Cordero J, Rubio K, Dobersch S, Gunther S, et al. MiCEE is a ncRNA-protein complex that mediates epigenetic silencing and nucleolar organization. Nat Genet. 2018;50:990–1001. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myant K, Stancheva I. LSH cooperates with DNA methyltransferases to repress transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:215–26. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01073-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tubbs A, Nussenzweig A. Endogenous DNA damage as a source of genomic instability in cancer. Cell. 2017;168:644–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Unoki M, Funabiki H, Velasco G, Francastel C, Sasaki H. CDCA7 and HELLS mutations undermine nonhomologous end joining in centromeric instability syndrome. J Clin Investig. 2019;129:78–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI99751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aguilera A, Garcia-Muse T. Causes of genome instability. Annu Rev Genet. 2013;47:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scully R, Panday A, Elango R, Willis N. DNA double-strand break repair-pathway choice in somatic mammalian cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:698–714. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson SP. Sensing and repairing DNA double-strand breaks. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:687–96. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dimitrova N, de Lange T. Cell cycle-dependent role of MRN at dysfunctional telomeres: ATM signaling-dependent induction of nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) in G1 and resection-mediated inhibition of NHEJ in G2. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5552–63. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00476-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahaney B, Meek K, Lees-Miller S. Repair of ionizing radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks by non-homologous end-joining. Biochemical J. 2009;417:639–50. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basenko E, Kamei M, Ji L, Schmitz R, Lewis Z. The LSH/DDM1 homolog MUS-30 is required for genome stability, but not for DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He YF, Ren JK, Xu XP, Ni K, Schwader A, Finney R, et al. Lsh/HELLS is required for B lymphocyte development and immunoglobulin class switch recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:20100–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004112117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kollárovič G, Topping C, Shaw E, Chambers A. The human HELLS chromatin remodelling protein promotes end resection to facilitate homologous recombination and contributes to DSB repair within heterochromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:1872–85. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Syed A, Tainer J. The MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 complex conducts the orchestration of damage signaling and outcomes to stress in DNA replication and repair. Annu Rev Biochem. 2018;87:263–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sartori A, Lukas C, Coates J, Mistrik M, Fu S, Bartek J, et al. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature. 2007;450:509–14. doi: 10.1038/nature06337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paull T. Mechanisms of ATM activation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:711–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu L, Luo K, Lou Z, Chen J. MDC1 regulates intra-S-phase checkpoint by targeting NBS1 to DNA double-strand breaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11200–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802885105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li J, Stern DF. DNA damage regulates Chk2 association with chromatin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37948–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509299200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kakarougkas A, Ismail A, Klement K, Goodarzi A, Conrad S, Freire R, et al. Opposing roles for 53BP1 during homologous recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:9719–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burrage J, Termanis A, Geissner A, Myant K, Gordon K, Stancheva I. The SNF2 family ATPase LSH promotes phosphorylation of H2AX and efficient repair of DNA double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. J cell Sci. 2012;125:5524–34. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spruce C, Dlamini S, Ananda G, Bronkema N, Tian H, Paigen K, et al. HELLS and PRDM9 form a pioneer complex to open chromatin at meiotic recombination hot spots. Genes Dev. 2020;34:398–412. doi: 10.1101/gad.333542.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roos W, Krumm A. The multifaceted influence of histone deacetylases on DNA damage signalling and DNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:10017–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller K, Tjeertes J, Coates J, Legube G, Polo S, Britton S, et al. Human HDAC1 and HDAC2 function in the DNA-damage response to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1144–51. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnson D, Spitz G, Tharkar S, Quayle S, Shearstone J, Jones S, et al. HDAC1,2 inhibition impairs EZH2- and BBAP-mediated DNA repair to overcome chemoresistance in EZH2 gain-of-function mutant diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:4863–87. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubio K, Singh I, Dobersch S, Sarvari P, Gunther S, Cordero J, et al. Inactivation of nuclear histone deacetylases by EP300 disrupts the MiCEE complex in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2229. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10066-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee SJ, Jang H, Park C. Maspin increases Ku70 acetylation and Bax-mediated cell death in cancer cells. Int J Mol Med. 2012;29:225–30. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang R, Liu N, Chen L, Jiang Y, Shi Y, Mao C, et al. GIAT4RA functions as a tumor suppressor in non-small cell lung cancer by counteracting Uchl3-mediated deubiquitination of LSH. Oncogene. 2019;38:7133–45. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang R, Liu N, Chen L, Jiang Y, Shi Y, Mao C, et al. LSH interacts with and stabilizes GINS4 transcript that promotes tumourigenesis in non-small cell lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res: CR. 2019;38:280. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1276-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Waseem A, Ali M, Odell E, Fortune F, Teh M. Downstream targets of FOXM1: CEP55 and HELLS are cancer progression markers of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:536–42. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mao C, Wang X, Liu Y, Wang M, Yan B, Jiang Y, et al. A G3BP1-interacting lncRNA promotes ferroptosis and apoptosis in cancer via nuclear sequestration of p53. Cancer Res. 2018;78:3484–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen L, Shi Y, Liu N, Wang Z, Yang R, Yan B, et al. DNA methylation modifier LSH inhibits p53 ubiquitination and transactivates p53 to promote lipid metabolism. Epigenetics Chromatin 2019;12:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Peng X, Sun J, Long Y, Xiao D, Zhou J, Tao Y, et al. The significance of HOXC11 and LSH in survival prediction in gastric adenocarcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2021;14:1517–29. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S273195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang R, Liu G, Han L, Qiu Y, Wang L, Wang M. MiR-365a-3p-mediated regulation of HELLS/GLUT1 axis suppresses aerobic glycolysis and gastric cancer growth. Front Oncol. 2021;11:616390. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.616390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 74.Long J, Xia A, Liu J, Jing J, Wang Y, Qi C, et al. Decrease in DNA methylation 1 (DDM1) is required for the formation of CHH islands in maize. J Integr Plant Biol. 2019;61:749–64. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jiang Y, Mao C, Yang R, Yan B, Shi Y, Liu X, et al. EGLN1/c-Myc induced lymphoid-specific helicase inhibits ferroptosis through lipid metabolic gene expression changes. Theranostics. 2017;7:3293–305. doi: 10.7150/thno.19988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu Y, Mao C, Wang M, Liu N, Ouyang L, Liu S, et al. Cancer progression is mediated by proline catabolism in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2020;39:2358–76. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-1151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dixon S, Stockwell B. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu, N, Lin, X, Huang, C. Activation of the reverse transsulfuration pathway through NRF2/CBS confers erastin-induced ferroptosis resistance. Br J Cancer. 2019. 10.1038/s41416-019-0660-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Myant K, Termanis A, Sundaram A, Boe T, Li C, Merusi C, et al. LSH and G9a/GLP complex are required for developmentally programmed DNA methylation. Genome Res. 2011;21:83–94. doi: 10.1101/gr.108498.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.He X, Yan B, Liu S, Jia J, Lai W, Xin X, et al. Chromatin remodeling factor LSH drives cancer progression by suppressing the activity of fumarate hydratase. Cancer Res. 2016;76:5743–55. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.von Eyss B, Maaskola J, Memczak S, Möllmann K, Schuetz A, Loddenkemper C, et al. The SNF2-like helicase HELLS mediates E2F3-dependent transcription and cellular transformation. EMBO J. 2012;31:972–85. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rawłuszko-Wieczorek A, Siera A, Jagodziński P. TET proteins in cancer: current ‘state of the art’. Crit Rev Oncol/Hematol. 2015;96:425–36. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Spruijt C, Gnerlich F, Smits A, Pfaffeneder T, Jansen P, Bauer C, et al. Dynamic readers for 5-(hydroxy)methylcytosine and its oxidized derivatives. Cell. 2013;152:1146–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu N, Yang R, Shi Y, Chen L, Liu Y, Wang Z, et al. The cross-talk between methylation and phosphorylation in lymphoid-specific helicase drives cancer stem-like properties. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:197. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00249-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen D, Maruschke M, Hakenberg O, Zimmermann W, Stief C, Buchner A. TOP2A, HELLS, ATAD2, and TET3 are novel prognostic markers in renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2017;102:265.e261–265.e267. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yan X, Dong X, Liu L, Yang Y, Lai J, Guo Y. DNA methylation signature of intergenic region involves in nucleosome remodeler DDM1-mediated repression of aberrant gene transcriptional read-through. J Genet genomics = Yi Chuan Xue Bao. 2016;43:513–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Corem S, Doron-Faigenboim A, Jouffroy O, Maumus F, Arazi T, Bouché N. ddm1Redistribution of CHH methylation and small interfering RNAs across the Genome of Tomato Mutants. Plant cell. 2018;30:1628–44. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ito T, Tarutani Y, To T, Kassam M, Duvernois-Berthet E, Cortijo S, et al. Genome-wide negative feedback drives transgenerational DNA methylation dynamics in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kinoshita Y, Saze H, Kinoshita T, Miura A, Soppe W, Koornneef M, et al. Control of FWA gene silencing in Arabidopsis thaliana by SINE-related direct repeats. Plant J: Cell Mol Biol. 2007;49:38–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zemach A, Kim M, Hsieh P, Coleman-Derr D, Eshed-Williams L, Thao K, et al. The Arabidopsis nucleosome remodeler DDM1 allows DNA methyltransferases to access H1-containing heterochromatin. Cell. 2013;153:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lyons, D, Zilberman, D. DDM1 and Lsh remodelers allow methylation of DNA wrapped in nucleosomes. eLife. 2017;6:e30674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Tan F, Lu Y, Jiang W, Wu T, Zhang R, Zhao Y, et al. DDM1 represses noncoding RNA expression and RNA-directed DNA methylation in heterochromatin. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:1187–97. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang D, Qu Z, Yang L, Zhang Q, Liu Z, Do T, et al. Transposable elements (TEs) contribute to stress-related long intergenic noncoding RNAs in plants. Plant J: Cell Mol Biol. 2017;90:133–46. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Litwin I, Bakowski T, Maciaszczyk-Dziubinska E, Wysocki R. The LSH/HELLS homolog Irc5 contributes to cohesin association with chromatin in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:6404–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mao C, Wang M, Qian B, Ouyang L, Shi Y, Liu N, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activated by benzo (a) pyrene promotes SMARCA6 expression in NSCLC. Am J Cancer Res. 2018;8:1214–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data analysed in Fig. 2 were extracted from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). The overall survival rate graph of NSCLC is from the study conducted by Mao et al., and the usage of the graph was approved (PMID: 30094095).