Abstract

Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) of 99 Brucella isolates, including the type strains from all recognized species, revealed a very limited genetic diversity and supports the proposal of a monospecific genus. In MLEE-derived dendrograms, Brucella abortus and a marine Brucella sp. grouped into a single electrophoretic type related to Brucella neotomae and Brucella ovis. Brucella suis and Brucella canis formed another cluster linked to Brucella melitensis and related to Rhizobium tropici. The Brucella strains tested that were representatives of the six electrophoretic types had the same rRNA gene restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns and identical ribotypes. All 99 isolates had similar chromosome profiles as revealed by the Eckhardt procedure.

Brucellosis is a worldwide zoonosis that is especially prevalent in northern and central agricultural regions of Mexico (27). Brucella was once considered to be related to the genera Bordetella and Alcaligenes (18). Later on, molecular biology techniques indicated that Brucella had taxonomic affiliation with members of the CDC group Vd (8), and an analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences confirmed its inclusion in the α2 subdivision of the Proteobacteria class (31). Since the position of the nodes in 16S rRNA gene phylogenetic trees is not without uncertainty (28), the position of Brucella within the α-proteobacteria has not been clearly determined. Furthermore, ribosomal genes in Brucella have been implicated in recombination events that promoted the division of a chromosome into two chromosomes (19).

Genetic relatedness within Brucella has been based on a comparison of omp2 sequences (10) and DNA restriction maps obtained from various species (30). Molecular probes have been developed for typing Brucella strains (6, 14), and PCR methods are available as diagnostic techniques (22, 23). The high levels of DNA-DNA relatedness among Brucella species led to the conclusion that Brucella was a monospecific genus (43).

Recently, genes involved in symbiosis in Sinorhizobium meliloti (the best-studied rhizobium with regard to its symbiotic determinants) have been found to be homologous to genes implicated in the pathogenesis of Brucella. Rhizobia (comprising the genera Allorhizobium, Azorhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Rhizobium, and Sinorhizobium) form nitrogen-fixing nodules; Brucella spp., on the other hand, are intracellular animal pathogens. The rhizobial bac genes participating in bacteroid differentiation (12) are homologous to genes which play a role in Brucella survival in macrophages as well as in mice pathogenesis (24). A two-component regulatory system BvrR and BvrS (Brucella virulence) is similar to exoS genes of S. meliloti. Brucella mutants in BvR and BvrS have a reduced capacity to invade macrophages and do not replicate intracelullarly (39). The S. meliloti periplasmic protease encoding gene degP is more similiar to the corresponding Brucella abortus gene than to that of Escherichia coli (12).

Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) has been frequently used to determine the genetic relatedness in bacteria, including E. coli (40), Salmonella spp. (38), and Vibrio cholerae (3). This technique has proven to be valuable in the characterization of emergent epidemic clones (3). The aim of the present study was to characterize Brucella spp. originating from different sources by MLEE and to compare the data to data obtained for rhizobia and agrobacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and cultures.

Brucella strains (75 isolates) (Table 1) originating from Mexico and abroad were isolated from human, animal, and dairy products. Also included in this study were 4 vaccine strains, 20 type strains from all different Brucella species and biovars, and Rhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Sinorhizobium, and Bradyrhizobium reference strains from the Centro de Investigación sobre Fijación de Nitrógeno (UNAM) collection and Ochrobactrum anthropi (23) and Agrobacterium spp. reference strains (36). Ochrobactrum and Brucella isolates were grown in soybean Trypticase (Difco) at 37°C, in Brucella agar, or in PY medium. Rhizobium strains were grown in PY medium (3 g of yeast extract, 5 g of peptone, and 0.7 g of calcium chloride per liter). All Brucella single-colony isolates were tested for their Gram reaction and for agglutination with anti-Brucella serum. Growth rates (not shown) were estimated for Brucella melitensis M16 and B. abortus 544 in order to determine harvesting times in the logarithmic phase of growth.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Species | Strains grouped according to source or reference

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine | Human blood and bone marrow | Dog blood | Goat milk | Cow milk and cheese | Unknown | ATCCa | |

| B. melitensis bv. 1 | REV-1 | 78, 87, 91, 113, 219, 256, 261, 376, 391, 392, 393, 400, 401, 402, 415, 450, 456, 457, 458, 461, 462, 485, LAR, P217 | 279, 280 | 371 | 23456 (M16) | ||

| B. melitensis bv. 2 | 84 | 23457 (63/9) | |||||

| B. melitensis bv. 3 | 254, 255, 257, 258, 259, 306 | G914, G1024, T65/40 | 23458 (Ether) | ||||

| B. abortus bv. 1 | S19, RB51 | ENCB | 223, 240, 264, 265, 266, 267, 268, 269, 270, 271, 272, 275, 307, 308, 309, 311, 312, 313, 314 | 23448 (544) | |||

| B. abortus bv. 2 | 23449 (86/8/59) | ||||||

| B. abortus bv. 3 | 23450 (Tulya) | ||||||

| B. abortus bv. 4 | 159, 160, 241, 242, 245 | 23451 (292) | |||||

| B. abortus bv. 5 | 273, 274 | 49/8 | 23452 (B3196) | ||||

| B. abortus bv. 6 | 23453 (870) | ||||||

| B. abortus bv. 7 | 23454 (63/75) | ||||||

| B. abortus bv. 9 | 23455 (C68) | ||||||

| B. suis bv. 1 | S2CH | 106, 387 | 196 | 129, 191, 192, 377 | 23444 (1330) | ||

| B. suis bv. 2 | 23445 (Thomsen) | ||||||

| B. suis bv. 3 | 23446 (686) | ||||||

| B. suis bv. 4 | 23447 (40/67) | ||||||

| B. suis bv. 5 | None (513) | ||||||

| B. canis | ISLE, 1226 | 23365 (RM6/66) | |||||

| B. ovis | 23840 (63/290) | ||||||

| B. neotomae | 23459 (5K33) | ||||||

| Marine Brucella | 14-95 | ||||||

Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization names and numbers are in parentheses.

MLEE.

Fresh liquid (1 ml) cultures (at 0.5 turbidity, MacFarland nephelometer) were used to inoculate 40-ml portions of PY media, which were shaken for 36 to 48 h at 37°C. Cell pellets obtained by centrifugation were washed, resuspended in 300 μl of 10 mM MgSO4 containing lysozyme (300 μg per ml) and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Cell lysis was achieved by freezing and thawing at −70°C for two 15-min cycles, and the resulting extracts were maintained at −70°C.

Gel electrophoresis was carried out in starch gels, and enzymatic activities were detected as described by Selander et al. (37). The enzymes assayed were the isocitrate, malate, glucose-6-phosphate, glutamate, and pyruvate dehydrogenases, plus indophenol oxidase, hexokinase, aconitase, phosphoglucomutase, and phosphoglucose isomerase and, additionally, for the 16-enzyme assays, the xanthine, alcohol, aspartate, threonine, and leucine dehydrogenases and glucosyltransferase. The different alleles (mobility variants for each enzyme) were numbered according to mobility. Electrophoretic types (ETs) were grouped from a pairwise matrix of genetic distances using the method described by Nei and Li (32). The genetic diversity (h) for each locus was calculated as h = 1 − Σx2[n/(n − 1)], where x is the frequency of the ith allele and n is the number of ETs or isolates in the population; H is the arithmetic average of all h values.

Amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis (ARDRA).

PCR products of 16S rRNA genes were synthesized with primers fD1 and rD1 (44) that correspond to positions 8 to 27 and positions 1524 to 1540 of the E. coli gene. PCR products were digested with 5 U of the restriction enzymes MspI, HinfI, HhaI, and Sau3AI, and DNA fragments were separated in 3% agarose gels (21). The PCR product of citrate synthase of B. melitensis M16 DNA was obtained with the Rhizobium tropici primers 512 MAP (TAC-AAG-TAC-CAT-ATC-GGC-CAG-CCC-TT), corresponding to bases 858 to 873, and primer CIR97037 (CCC-ATC-ATG-CGG-AAC-GGA-TC), corresponding to bases 1218 to 1237.

DNA extraction and Southern blot hybridization.

DNA was purified, blotted onto nylon filters, and hybridized to the PCR 16S rRNA gene product from B. melitensis M16, to the total DNA from the same strain labeled with 32P by RediPrime (Amersham), or to the PCR-synthesized citrate synthase gene. DNA-DNA hybridization was performed from Southern blots, and washings were performed either at 0.1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) (high) or at 1× SSC (low) stringency.

Eckhardt gel electrophoresis.

The modified procedure by Hynes and McGregor (16) involving a gentle lysis of the cell pellet with lysozyme and sodium dodecyl sulfate (incorporated into the agarose gel [agarose Sigma Type 1:Low EEO, catalog number A-6013]) was used with early-log-phase bacteria grown in PY medium. Horizontal gels were run at 80 V for 10 h at room temperature. Plasmid sizes were estimated using S. meliloti megaplasmids (1.4 and 1.7 Mb [2]) as references. The miniscreening procedure (4) was also used in order to visualize small plasmids.

RESULTS

Most human isolates from Mexico corresponded to B. melitensis bv. 1, and a majority of dairy product isolates corresponded to B. abortus bv. 1 based on the traditional classification methods (27). We did not isolate Brucella ovis and Brucella neotomae. The H value among the four Brucella ETs obtained with 10 enzymes was 0.16, and the H value calculated for all isolates was 0.04. Representatives from each ET and some R. tropici and Ochrobactrum strains were analyzed with an additional six enzymes in order to reveal further diversity (Table 2). This resulted in two of the Brucella spp. ETs being split into two related ETs, while the other ETs remained unaltered. Each Brucella species was distinguishable by its ET with 16 enzymes (Table 2; see Fig. 2). The total number of ETs obtained with Brucella isolates was six, and the H value among the six ETs was 0.32. If we consider that six ETs represent all of the 99 strains tested, then the strain/ET ratio would be 16.5, a value higher than that encountered (ca. 1) from single-species Rhizobium populations. The high strain/ET ratio encountered in Brucella spp. is an indicator of a limited genetic diversity that is also revealed by the low number of polymorphic enzymes detected (9 of 16).

TABLE 2.

Allele profiles of the 16 metabolic enzymes testeda

| Strain | Allele profile of:

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDH | MDH | G6P | GDH | PDH | IPO | HEX | ACO | PGM | PGI | XDH | ADH | ASD | THD | LED | GTF | |

| O. anthropi 95/5 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| B. suis 1330 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 |

| B. suis 4 40/67 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 |

| B. canis RM6/66 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 |

| B. canis 1226 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 |

| R. tropici CIAT 899 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 |

| R. tropici CFN 299 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 |

| B. melitensis M16 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 |

| B. melitensis 84 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 |

| B. abortus 3 Tulya | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| B. abortus 544 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Marine Brucella 14/95 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| B. neotomae 5K33 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| B. ovis 63/290 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

Enzyme abbreviations: IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; MDH, malate dehydrogenase; G6P, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; GDH, NADP-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; IPO, indophenol oxidase; HEX, hexokinase; ACO, aconitase; PGM, phosphoglucomutase; PGI, phosphoglucose isomerase; XDH, xanthine dehydrogenase; ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase; ASD, aspartate dehydrogenase; THD, threonine dehydrogenase; LED, leucine dehydrogenase; GTF, glucosyltransferase.

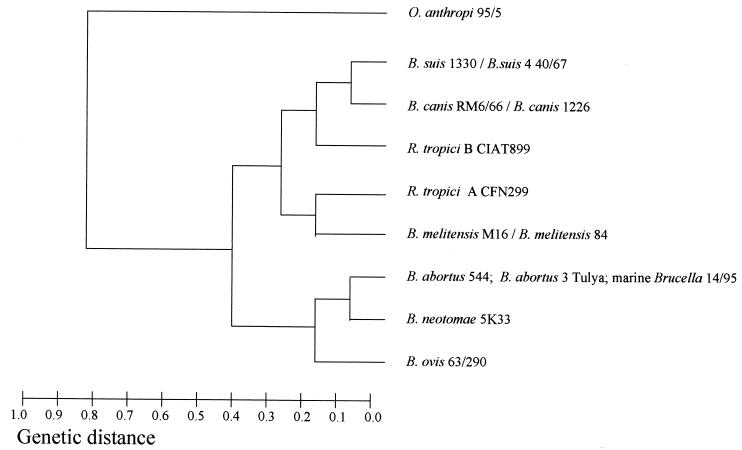

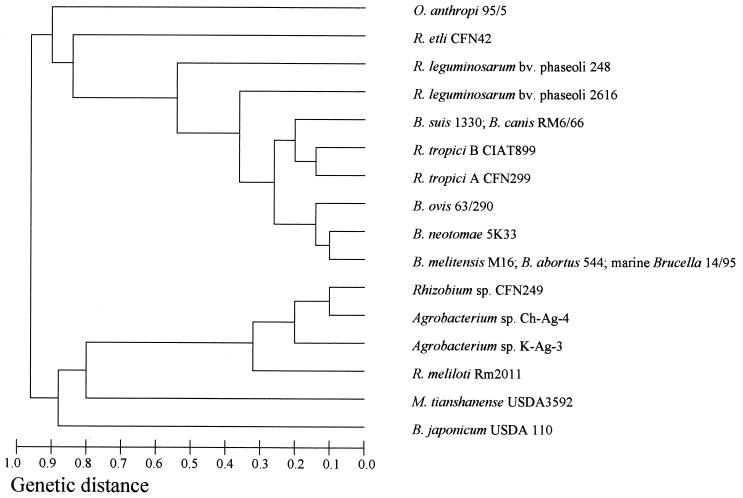

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram derived from MLEE with 16 enzymes analyzed (see Materials and Methods).

The MLEE-derived dendrogram obtained with Brucella spp. and rhizobia confirms their close relationship (Fig. 1 and 2). With the 16-enzyme analysis, two subclusters may be distinguished for Brucella isolates, one with the marine Brucella, B. abortus, B. neotomae, and B. ovis, and the other with B. canis, B. suis, and B. melitensis. R. tropici strains grouped with the second subcluster. O. anthropi and Agrobacterium spp. were related to Brucella at a genetic distance of 0.9 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram derived from MLEE with 10 enzymes analyzed: isocitrate dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, NADP-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase, pyruvate dehydrogenase, indophenol oxidase, hexokinase, aconitase, phosphoglucomutase, and phosphoglucose isomerase.

A single pattern with three common bands was observed when EcoRI-DNA digestion fragments of several Brucella species (B. melitensis M16 and 84; B. abortus bv. 1, 544, and bv. 3 Tulya; B. neotomae 5K33; B. suis bv. 1, 1330, bv. 4, 40/67; the marine Brucella sp. strain 14/95; B. canis 1226) were hybridized in Southern blottings using the 16S rRNA gene PCR product of B. melitensis M16 as a probe. Three rrn loci have been found in Brucella spp. (30). ARDRA analysis revealed that the Brucella strains listed above shared a common rRNA gene pattern (data not shown).

DNA-DNA homology values indicated that Ochrobactrum and Brucella spp. were more homologous (ca. 30%) than Brucella spp. and rhizobia (ca. 10%). At high stringency, a slightly higher percentage of hybridization is obtained with R. tropici than with S. meliloti, but this may not be significant.

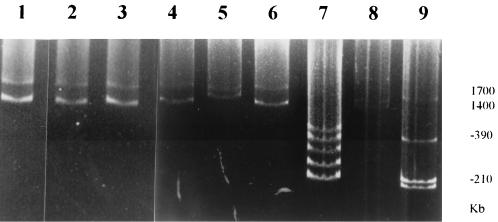

Interestingly, Brucella chromosomes were easily visualized with the Eckhardt procedure that we normally use to reveal plasmids and megaplasmids in rhizobia. Most of the strains had the same pattern corresponding to chromosomes of 2.05 and 1.15 Mb. No large or small plasmids were encountered in any of the 99 isolates tested. Two chromosomes of 1.35 and 1.85 Mb were observed with B. suis bv. 2 and bv. 4 in agreement with the data of Jumas-Bilak (19). The only discrepancy with the reported results was obtained with B. suis biovar 3 which contained smaller chromosomes (2.1 and 1.15 Mb) than that (3.2 Mb) observed by Jumas-Bilak (19). In order to resolve this discrepancy, we analyzed chromosomes from at least two additional B. suis bv. 3 strains from different sources, and the data confirmed our previous findings (Fig. 3). Both chromosomes from each Brucella strain hybridized to the 16S rRNA gene probe, while only the larger one hybridized to the citrate synthase gene (not shown). The megaplasmid of R. tropici, which is similar in size to the smaller chromosome of B. suis bv. 2 and 4, did not hybridize to the homologous 16S rRNA DNA gene probe as was reported previously (11).

FIG. 3.

Plasmid megaplasmids and chromosomes as visualized by the modified Eckhardt procedure. Lanes: 1, B. abortus bv. 1; 2, B. melitensis bv. 1; 3, B. abortus bv. 4; 4, B. suis bv. 3; 5, B. suis bv. 4; 6, B. suis bv. 5; 7, R. etli CFN42; 8, R. meliloti 1021; 9, R. tropici type A reference strain CFN299.

DISCUSSION

MLEE analysis is a useful standard method for evaluating bacterial genetic diversity. In general, a different species is recognized if a genetic distance larger than 0.5 is observed. The limited genetic variation exhibited by the Brucella isolates is congruent with a monospecific genus (43). The fact that only a few clones (ETs) were obtained that are conserved through space and time probably reflects a recent origin of the genus. The H value for all Brucella species was 0.04 or 0.32 (depending if the analysis is on an isolate or ET basis), which is smaller than those normally estimated for a single Rhizobium species (ca. 0.5) (29). A large diversity has been encountered in rhizobia, suggesting that they represent very old lineages. Pathogens, especially those occurring intracellularly, have a narrow diversity which may reflect their habitat constraints (reviewed in reference 29). Thus, limited genetic diversity has also been obtained with Yersinia ruckeri and Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi B.

A close relationship of B. suis and B. canis was recognized based on phenotypic characteristics (1), and these organisms were not distinguishable by their physical maps (30). From our data, B. suis is very similar to B. canis and is only distinguishable by 1 enzyme, xanthine dehydrogenase, of 16. In general, our dendrograms obtained by MLEE are in good agreement with the one constructed on the basis of the sequence of omp2 (10), and both methods are in general agreement with the tree derived from genome restriction maps (30). Originally, one isolate from a marine animal was considered related to B. abortus or B. melitensis (9). We could not distinguish the marine Brucella sp. from B. abortus by MLEE; however, we included only a single isolate from marine mammals. An extensive analysis of Brucella spp. in marine mammals showed that they possessed DNA fingerprints that differentiated them from other described Brucella species (5). The two B. suis bv. 5 strains tested had ETs corresponding to B. melitensis (determined with the 16-enzyme analysis) and not to the B. suis ET. The question regarding whether B. suis bv. 5 strains are bona fide B. suis was raised earlier based on metabolic profiles and susceptibility to phages (17).

It is possible that genetic variation may be underestimated by MLEE because different alleles may have identical mobilities (33). Variation within an ET may be revealed by DNA-based fingerprinting methods. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi was found to have a worldwide limited genetic diversity and a clonal population structure as revealed with MLEE (38). Variation within serovar Typhi clones was shown with ribosomal fingerprinting. These results may be explained if ribosomal gene rearrangements (26) and recombination occurred faster than detectable changes in isoenzymes. Thus, MLEE would allow for the detection of older genetic relationships, as we suppose is the case with R. tropici and Brucella. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, another intracellular human and animal pathogen, which has been found to be genetically very homogeneous, is considered to have evolved relatively recently from a soil bacterium (7, 41). Our hypothesis is that both Brucella and R. tropici have a common ancestor and have conserved the type of inherited alloenzymes. We further suppose that these enzymes were adapted to an acid intracellular environment. R. tropici has been described as highly tolerant to acidity in comparison to many other Rhizobium species, including S. meliloti (13), whereas Brucella spp. must survive low gastric pH, and an adaptive acid tolerance response has been described (20). Tolerance to acidity allows the survival of other bacteria in cheese (25), and Brucella is normally encountered in fermented dairy products. Our suggestion of a common origin of Brucella and Rhizobium spp. certainly agrees with the proposal that a larger chromosome (as in Rhizobium) gave rise to the two smaller chromosomes found in Brucella (19).

The DNA-DNA hybridization results showed that Brucella was more homologous to Ochrobactrum (30% DNA-DNA hybridization) than to R. tropici (12%). It is worth noting that the percentage of total DNA-DNA homology among Brucella spp. and S. meliloti or R. tropici (ca. 11%) is lower than the percentage of nucleotide identity encountered when different homologous genes are compared. For example, Brucella and S. meliloti degP gene sequences are 55.5% identical; a fragment of 400 bp of pckA gene (for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase) is 77% identical among Sinorhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and B. abortus (39, 35), and the citrate synthase gene of Brucella is about 80% identical to the corresponding gene in R. tropici (our unpublished results and reference 15). A fragment of phospholipid N-methyltranferase (pmtA) genes of B. ovis and S. meliloti are 61% identical (O. Geiger, personal communication). This may mean that some parts of the Brucella genome are shared with rhizobia, while others may have been acquired from other sources. The MLEE relationships observed between Brucella and rhizobia may be explained if the common genome encodes the metabolic enzymes we have analyzed. In contrast, similarities in genes coding for a secretion system of B. suis and Bordetella pertussis have been reported (34). It is intriguing that in spite of the fact that Ochrobactrum isolates, especially O. intermedia, are clearly related to Brucella (42), we did not detect a high degree of similarity among Brucella and Ochrobactrum isolates by MLEE. Ochrobactrum has been shown to be highly diverse. This diversity may be the result of extensive interstrain recombination with randomization of enzymatic alleles. Notably, R. tropici type A and type B share only 36% DNA-DNA homology, yet they are considered to constitute a single species. Finally, the easy and clear detection of the chromosomes of Brucella spp. in Eckhardt gels may be useful in Brucella research to determine whether a gene is present on a specific replicon (as we have shown with the citrate synthase gene) and for further characterization or even identification of new isolates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Martínez Romero for technical support, L. Barran and M. Dunn for critically reviewing the manuscript, and A. MacMillan for providing the marine Brucella and O. anthropi strains.

B.G.J. was supported by a graduate student scholarship from CONACyT and PIFI-IPN, and A.L.M. was supported by a research scholarship from COFAA-IPN. This work was also supported by grants from CONACyT (27594B) and CGPI-IPN (980367).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allardet-Servent A, Bourg G, Ramuz M, Pages M, Bellis M, Roizes G. DNA polymorphism in strains of the genus Brucella. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4603–4607. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4603-4607.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barloy-Hubler F, Capela D, Barnett M J, Kalman S, Federspiel N A, Long S R, Galibert F. High-resolution physical map of the Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 pSyma megaplasmid. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1185–1189. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.1185-1189.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltran P, Delgado G, Navarro A, Trujillo F, Selander R K, Cravioto A. Genetic diversity and population structure of Vibrio cholerae. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:581–590. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.581-590.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bricker B J, Ewalt D R, MacMillan A P, Foster G, Brew S. Molecular characterization of Brucella strains isolated from marine mammals. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1258–1262. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1258-1262.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bricker B J, Halling S M. Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv1, 2 and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv.1 by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2660–2666. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2660-2666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Ley J, Mannheim W, Segers P, Lievens A, Denjin M, Vanhoucke M, Gillis M. Ribosomal ribonucleic acid cistron similarities and taxonomic neighborhood of Brucella and CDC group Vd. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1987;37:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ewalt D R, Payeur J B, Martin B M, Cummins D R, Miller W G. Characteristics of a Brucella species from a bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) J Vet Diagn Investig. 1994;6:448–452. doi: 10.1177/104063879400600408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ficht T A, Husseinen H S, Derr J, Bearden S W. Species-specific sequences at the omp2 locus of Brucella type strains. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:329–331. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geniaux E, Flores M, Palacios R, Martínez E. Presence of megaplasmids in Rhizobium tropici and further evidence of differences between the two R. tropici subtypes. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:392–394. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glazebrook J, Ichige A, Walker G C. Genetic analysis of Rhizobium meliloti bacA-phoA fusion results in identification of degP: two loci required for symbiosis are closely linked to degP. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:745–752. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.745-752.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham P H, Draeger K J, Ferrey M L, Conroy M J, Hammer B E, Martínez E, Aarons S R, Quinto C. Acid pH tolerance in strains of Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium, and initial studies on the basis for acid tolerance of Rhizobium tropici UMR 1899. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:198–207. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimont F, Verger J M, Cornelis P, Limet J, Lefèvre M, Grayon M, Régnault B, Van Broeck J, Grimont P A D. Molecular typing of Brucella with cloned DNA probes. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:55–65. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90034-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernández-Lucas I, Pardo M A, Segovia L, Miranda J, Martínez-Romero E. Rhizobium tropici chromosomal citrate synthase gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3992–3997. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.3992-3997.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hynes M F, McGregor N F. Two plasmids other than the nodulation plasmid are necessary for formation of nitrogen-fixing nodules by Rhizobium leguminosarum. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:567–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jahans K L, Foster G, Broughton E S. The characteristics of Brucella strains isolated from marine mammals. Vet Microbiol. 1997;57:373–382. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson R, Sneath P H A. Taxonomy of Bordetella and related organisms of the families Achromobacteriaceae, Brucellaceae, and Neisseriaceae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1973;23:381–404. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jumas-Bilak E, Michaux-Charachon S, Bourg G, O'Callaghan D, Ramuz M. Differences in chromosome number and genome rearrangements in the genus Brucella. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:99–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulakov Y K, Guigue-Talet P G, Ramuz M R, O'Callaghan D. Response of Brucella suis 1330 and B. canis RM6/66 to growth at acid pH and induction of an adaptive acid tolerant response. Res Microbiol. 1997;148:145–151. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(97)87645-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laguerre G, Allard M-R, Revoy F, Amarger N. Rapid identification of rhizobia by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:56–63. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.1.56-63.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leal-Klevezas D S, López-Merino A, Martínez-Soriano J P. Molecular detection of Brucella spp.: rapid identification of B. abortus biovar I using PCR. Arch Med Res. 1995;26:263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leal-Klevezas D S, Martínez-Vázquez I O, López Merino A, Martinez-Soriano J P. Single-step PCR for detection of Brucella spp. from blood and milk of infected animals. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3087–3090. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3087-3090.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeVier K, Phillips R W, Grippe V K, Roop II R M, Walker G C. Similar requirements of a plant symbiont and a mammalian pathogen for prolonged intracellular survival. Science. 2000;287:2492–2493. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5462.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leyer G J, Johnson E A. Acid adaptation promotes survival of Salmonella spp. in cheese. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2075–2080. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.2075-2080.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu S-L, Sanderson K E. Highly plastic chromosomal organization in Salmonella typhi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10303–10308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.López-Merino A. Brucelosis humana. In: López-Merino A, editor. Brucelosis: avances y perspectivas, México. Publicación técnica del INDRE-SSA no. 6. Mexico City, Mexico: Secretaría de Salud; 1991. pp. 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludwig W, Amann R, Martínez-Romero E, Schönhuber W, Bauer S, Neef A, Schleifer K-H. rRNA-based identification and detection systems for rhizobia and other bacteria. Plant Soil. 1998;204:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martínez-Romero E, Caballero-Mellado J. Rhizobium phylogenies and bacterial genetic diversity. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1996;15:113–140. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michaux-Charachon S, Bourg G, Jumas-Bilak E, Guigue-Talet P, Allardet-Servent A, O'Callaghan D, Ramuz M. Genome structure and phylogeny in the genus Brucella. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3244–3249. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3244-3249.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreno E, Stackebrandt E, Dorsch M, Wolters J, Busch M, Mayer H. Brucella abortus 16S rRNA and lipid A reveal a phylogenetic relationship with members of the α-2 subdivision of the class Proteobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3569–3576. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3569-3576.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nei M, Li W H. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:5269–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson K, Whittam T S, Selander R K. Nucleotide polymorphism and evolution in the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase genes (gapA) in natural populations of Salmonella and Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6667–6671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Callaghan D, Cazevielle C, Allardet-Servent A, Boschirolli M L, Bourg G, Foulongne V, Frutos P, Kulakov Y, Ramuz M. A homologue of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB and Bordetella pertussis Ptl type IV secretion systems is essencial for intracellular survival of Brucella suis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1210–1220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osteras M, Finan T M, Stanley J. Site-directed mutagenesis and DNA sequence of pckA of Rhizobium NGR234, encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase: gluconeogenesis and host-dependent symbiotic phenotype. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;230:257–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00290676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawada H, Ieki H. Phenotypic characteristics of the genus Agrobacterium. Ann Phytopathol Soc Japan. 1992;58:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selander R K, Caugant D A, Ochman H, Musser J M, Gilmour M N, Whittam T S. Methods of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for bacterial population genetics and systematics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:873–884. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.5.873-884.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selander R K, Beltran P, Smith N H, Helmuth R, Rubin F A, Kopecko D J, Ferris K, Tall B D, Cravioto A, Musser J M. Evolutionary genetic relationships of clones of Salmonella serovars that cause human typhoid and other enteric fevers. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2262–2275. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2262-2275.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sola-Landa A, Pizarro-Cerdá J, Grilló M-J, Moreno E, Moriyón I, Blasco J-M, Gorvel J P, López-Goñi I. A two-component regulatory system playing a critical role in plant pathogens and endosymbionts is present in Brucella abortus and controls cell invasion and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:125–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Souza V, Rocha M, Valera A, Eguiarte L E. Genetic structure of natural populations of Escherichia coli in wild hosts on different continents. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3373–3385. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3373-3385.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sreevatsan S, Pan X I, Stockbauer K E, Connell N D, Kreiswirth B N, Whittam T S, Musser J M. Restricted structural gene polymorphism in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex indicates evolutionarily recent global dissemination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9869–9874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Velasco J, Romero C, López-Goñi I, Leiva J, Díaz R, Moriyón I. Evaluation of the relatedness of Brucella spp. and Ochrobactrum anthropi and description of Ochrobactrum intermedium sp. nov., a new species with a closer relationship to Brucella spp. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:759–768. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-3-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verger J-M, Grimont F, Grimont P A D, Grayon M. Brucella, a monospecific genus as shown by deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1985;35:292–295. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weisburg W G, Barns S M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]