Abstract

BACKGROUND

Mindfulness meditation is beneficial to mitigate the negative effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in the general population, but no study examined such meditation in the COVID-19 patients themselves.

AIM

To explore the short-term efficacy of mindfulness meditation in alleviating psychological distress and sleep disorders in patients with COVID-19.

METHODS

This prospective study enrolled patients with mild COVID-19 treated at Wuhan Fangcang Hospital in February 2020. The patients were voluntarily divided into either a mindfulness or a conventional intervention group. The patients were evaluated before/after the intervention using the Short Inventory of Mindfulness Capability (SMI-C), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

RESULTS

Seventy-five participants were enrolled in this study, with 43 and 32 in the mindfulness and conventional groups, respectively. Before the intervention, there were no differences in SMI-C, HADS, or PSQI scores between the two groups. After the 2-wk intervention, the mindfulness level (from 30.16 ± 5.58 to 35.23 ± 5.95, P < 0.001) and sleep quality (from 12.85 ± 3.06 to 9.44 ± 3.86, P < 0.001) were significantly increased in the mindfulness group. There were no differences in the conventional group. After the intervention, the mindfulness level (35.23 ± 5.95 vs 31.17 ± 6.50, P = 0.006) and sleep quality (9.44 ± 3.86 vs 11.87 ± 4.06, P = 0.011) were significantly higher in the mindfulness group than in the conventional group. Depression decreased in the mindfulness group (from 14.15 ± 3.21 to 12.50 ± 4.01, P = 0.038), but there was no difference between the two groups.

CONCLUSION

Short-term mindfulness meditation can increase the mindfulness level, improve the sleep quality, and decrease the depression of patients with COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Mindfulness, Mental health, Sleep quality

Core Tip: The study aimed to explore the short-term efficacy of mindfulness meditation in alleviating psychological distress and sleep disorders in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). A 5-min mindfulness meditation audio induction can elevate the mindfulness levels and improve the sleep quality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. It is an effective, economical, and convenient non-drug psychological intervention that can be universally applied.

INTRODUCTION

The global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become the most severe public health threat in recent years[1,2]. From December 2019 to November 22, 2020, 57.8 million people were infected, and 1.3 million died[3]. Fever and respiratory symptoms of varying degrees are common manifestations of COVID-19[1,2]. Severe cases develop pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, renal failure, or death[1,2]. Owing to the strong infectivity and pathogenicity[4], the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China classified COVID-19 as a category B infectious disease that should be managed as a category A infectious disease[5].

Besides the pulmonary complications and mortality, COVID-19 has a psychological impact on the populations around the world, manifesting as depression, anxiety, panic attacks, and sleep disorders[5-8]. In Wuhan (China), the hardest-hit area of COVID-19 in China, the residents are prone to psychological problems[7,9]. For patients with COVID-19, fear of the disease and negative emotions easily lead to a psychological crisis, and timely and effective psychological interventions are of great significance[10-12].

Mindfulness meditation has been increasingly applied in clinical practice as a psychological intervention[13-16]. Relevant evidence has demonstrated that mindfulness meditation has pronounced effects on chronic diseases, sleep disorders, anxiety, and neurosis[14-19], especially for nurses who play critical roles in public health emergencies[20-22]. Mindfulness meditation is beneficial to mitigate the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population[23-26], but no study examined such meditation in the COVID-19 patients themselves.

Therefore, this study aimed to explore the efficacy of mindfulness meditation in alleviating psychological distress and sleep disorders in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan Fangcang Hospital. Mindfulness meditation might be beneficial to alleviate negative emotions and improve sleep quality in patients with COVID-19.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and subjects

This prospective study enrolled patients with mild COVID-19 treated at Wuhan Fangcang Hospital in February 2020. This study was approved by the ethics review board of Jiangsu Province Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Patients with COVID-19 treated at Wuhan Fangcang Hospital; (2) 18-60 years of age and normal hearing, reading, and language; and (3) No history of mental diseases, and clear verbal expression. All participants enrolled in this study were diagnosed according to World Health Organization interim guidance[27]. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Concurrent with comorbidities of vital organs; (2) Receiving other psychological interventions; or (3) History of mental diseases (e.g., schizophrenia).

Groups

The intervention was explained to each potential participant in detail. According to their wishes, the participants were divided into either a mindfulness or a conventional intervention group. There was no blinding.

Interventions

The participants in both groups were treated with the same supportive therapy for COVID-19.

In the conventional group, the participants received conventional care/education about admission, COVID-19, medication, physical examinations, psychological support, and safety education.

Mindfulness meditation induction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) were applied in the mindfulness intervention group. A 5-min mindfulness audio file produced by Li et al[28] was played using a mobile phone through WeChat. The participants were guided into mindfulness meditation according to the instructions in the audio file. During mindfulness meditation, the participants were asked to keep an alert and relaxed posture, with the eyes gently closed. At least 1 h of collective Q&A was performed in the participants each day, and face-to-face psychological support was provided if necessary. The research group included one registered psychiatrist and three registered nurses with a bachelor’s degree or above and at least 3 years of working experience. The psychiatrist was responsible for selecting the 5-min mindfulness audio instructions and for training the nurses about mindfulness knowledge and nursing precautions before and after playing the mindfulness instructions. A WeChat group was generated for the participants during the study period. On the first day of participation, the mindfulness meditation audio and texts were pushed via WeChat. The nurses guided the participants to meditate, and the induction lasted about 30 min. On the second day, after mastering the mindfulness meditation training methods, the participants were free to undergo a daily mindfulness meditation (5-20 min) before sleeping. The nurses directed and supervised the daily mindfulness meditation and recorded the sleep quality of the participants.

Outcomes

The Short Inventory of Mindfulness Capability (SIM-C) was used to assess the mindfulness level of the participants[29] using 12 items in three categories (i.e., acting with awareness, describing, and non-judging of experience). The SIM-C scores were determined using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (always true). A higher SIM-C score indicates a higher level of mindfulness.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to determine the levels of anxiety and depression in the participants[30] using seven items in two categories. Each item is weighed on a scale of 0-3. The total HADS score ranges from 0 to 21. A higher score indicates more severe anxiety or depression. HADS scores ranging from 9 to 21 indicate that a person is experiencing anxiety or depression.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to assess sleep quality[31] using 18 items and seven components (subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction). Each item is weighed on four-interval scales (0-3). The total PSQI score ranges from 0 to 21, where higher scores indicate worse sleep quality. Sleep disorders were determined with PSQI > 7. The patients were evaluated using SIM-C, HADS, and PSQI before and after the intervention.

Data collection

Demographic characteristics (including age, sex, body weight, height, and educational background) and SIM-C, HADS, and PSQI scores were recorded.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States) was used for statistical analyses. Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences between groups were analyzed using the independent-sample t test. Differences before and after the intervention were analyzed using the paired-sample t test. Categorical data are presented as n (%) and were analyzed using the chi-square test. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the participants

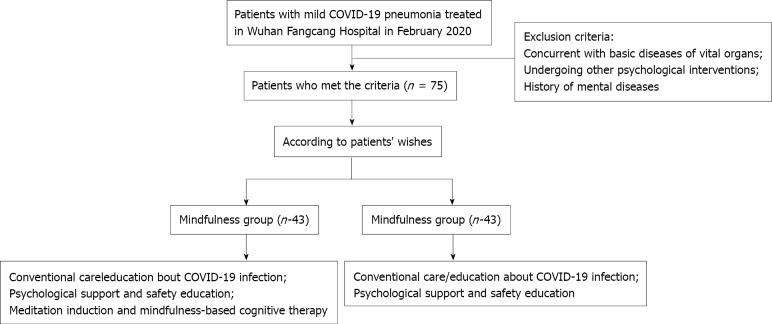

Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the participant enrollment process. In the mindfulness group, there were 30 males and 13 females; the participants were 42.23 ± 9.78 (range: 30-55) years of age. Eighteen males and fourteen females were enrolled in the conventional group; they were 44.35 ± 10.61 (range: 27-56) years of age (Table 1). There were no significant differences in SIM-C, HADS, or PSQI scores between the two groups before the intervention (P > 0.05; Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant enrollment process. COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with coronavirus disease 2019

|

Characteristic

|

Mindfulness group (n = 43)

|

Conventional group (n = 32)

|

P

|

| Age, yr (mean ± SD) | 42.23 ± 9.78 | 44.35 ± 10.61 | 0.069 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 30 (69.8) | 18 (56.2) | 0.228 |

| Female | 13 (30.2) | 14 (43.8) | |

| Height, cm (mean ± SD) | 169.51 ± 8.13 | 165.41 ± 8.46 | 0.037 |

| Weight, kg (mean ± SD) | 70.37 ± 12.52 | 64.97 ± 9.43 | 0.044 |

| Education, n (%) | 0.345 | ||

| Junior diploma or below | 6 (14.0) | 7 (21.9) | |

| High and technical secondary school diploma | 9 (20.9) | 7 (21.9) | |

| Junior college | 9 (20.9) | 10 (31.3) | |

| Bachelor degree or above | 19 (44.2) | 8 (25.0) |

Table 2.

Short Inventory of Mindfulness Capability, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores before and after intervention in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 between groups

|

|

Characteristic

|

Mindfulness group (n = 43)

|

Conventional group (n = 32)

|

P

|

| Before intervention | Mindfulness (mean ± SD) | 30.16 ± 5.58 | 29.42 ± 6.03 | 0.585 |

| Anxiety (mean ± SD) | 14.05 ± 2.56 | 13.60 ± 2.93 | 0.481 | |

| Depression (mean ± SD) | 14.15 ± 3.21 | 14.00 ± 2.97 | 0.837 | |

| Sleep quality (mean ± SD) | 12.85 ± 3.06 | 13.36 ± 4.12 | 0.572 | |

| After intervention | Mindfulness (mean± SD) | 35.23 ± 5.95b | 31.17 ± 6.50 | 0.006 |

| Anxiety (mean ± SD) | 12.91 ± 3.42 | 13.25 ± 2.83 | 0.649 | |

| Depression (mean ± SD) | 12.50 ± 4.01a | 13.52 ± 3.68 | 0.263 | |

| Sleep quality (mean ± SD) | 9.44 ± 3.86b | 11.87 ± 4.06 | 0.011 |

P < 0.05 vs before intervention in the mindfulness group.

P < 0.001 vs before intervention in the mindfulness group.

Table 3.

Short Inventory of Mindfulness Capability, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores before and after intervention in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 within groups

|

|

Mindfulness (mean ± SD)

|

Anxiety (mean ± SD)

|

Depression (mean ± SD)

|

Sleep quality (mean ± SD)

|

|

| Mindfulness group (n = 43) | Before intervention | 30.16 ± 5.58 | 14.05 ± 2.56 | 14.15 ± 3.21 | 12.85 ± 3.06 |

| After intervention | 35.23 ± 5.95 | 12.91 ± 3.42 | 12.50 ± 4.01 | 9.44 ± 3.86 | |

| P | < 0.001 | 0.084 | 0.038 | < 0.001 | |

| Conventional group (n = 32) | Before intervention | 29.42 ± 6.03 | 13.60 ± 2.93 | 14.00 ± 2.97 | 13.36 ± 4.12 |

| After intervention | 31.17 ± 6.50 | 13.25 ± 2.83 | 13.52 ± 3.68 | 11.87 ± 4.06 | |

| P | 0.269 | 0.629 | 0.568 | 0.150 | |

Mindfulness levels after intervention in patients with COVID-19

After the 2-wk intervention, the mindfulness level (from 30.16 ± 5.58 to 35.23 ± 5.95, P < 0.001) was significantly increased in the mindfulness group and was significantly higher in the mindfulness group than in the conventional group (35.23 ± 5.95 vs 31.17 ± 6.50, P = 0.006; Tables 2 and 3).

Sleep quality after the intervention

After the 2-wk intervention, sleep quality (from 12.85 ± 3.06 to 9.44 ± 3.86, P < 0.001) in the mindfulness group was significantly improved, but there was no change in the conventional group. The sleep quality (9.44 ± 3.86 vs 11.87 ± 4.06, P = 0.011) was significantly higher in the mindfulness group than in the conventional group, and the degree of sleep quality (P = 0.022) was significantly different between the two groups (Tables 2 and 3).

Anxiety and depression before and after the intervention

Before the intervention, the participants in both groups experienced anxiety and depression. After the 2-wk intervention, the depression level was decreased significantly in the mindfulness group (from 14.15 ± 3.21 to 12.50 ± 4.01, P = 0.038), but there was no change in the conventional group. There were no significant differences in anxiety (P = 0.649) or depression (P = 0.263) between the two groups after the intervention (Tables 2 and 3).

DISCUSSION

COVID-19 damages physical health and poses a huge impact on mental health because of the isolation, uncertainness about disease outcomes, and rumors, leading to anxiety, depression, and negative emotions during treatment[10-12]. Therefore, timely and effective psychological counseling should be implemented in the comprehensive therapy of COVID-19[10-12,32]. A strongly effective intervention is necessary to relieve the overwhelming negative emotions, thus decreasing ego depletion[33]. Mindfulness meditation is a unique practice to enhance attention and awareness, focusing on one’s internal and external experiences in a moment of conscious and non-judgmental awareness[13-16,33]. Mindfulness is conducive to the treatment of a variety of conditions[13-16]. It also helps to regulate emotions and enhances well-being. Furthermore, mindfulness can reduce unconscious behaviors and overcome automaticity[13-16,34]. Mindfulness meditation is beneficial to mitigate the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population[23-26], but no study examined such meditation in the COVID-19 patients themselves. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the efficacy of mindfulness meditation in alleviating psychological distress and sleep disorders in patients with COVID-19. The results suggested that a short-term (2-wk) mindfulness induction can increase the mindfulness level, improve the sleep quality, and decrease the depression of patients with COVID-19.

The Wuhan Fangcang Hospital is a temporary hospital constructed to treat COVID-19 and has relatively crude facilities. Wuhan Fangcang Hospital has 1000 beds to isolate patients with COVID-19. A narrow space, a brightly lit environment, and strict protective measures (e.g., masks and protective clothing) enhance negative emotions. This hospital serves public health purposes in terms of physical care and isolation on the patients, but the environment is not conducive to mitigating stress and anxiety. In this hospital and this study, a short-term mindfulness meditation audio file that only takes 15-20 min could significantly enhance the patients' mindfulness by eliminating distractions and focusing on the current awareness.

Fear in response to life-threatening events is common in human beings[35,36]. An effective psychological intervention can elevate mindfulness levels, thereby offering the patient a positive attitude towards diseases. Mindfulness meditation originates from the ancient orient[37] and is closely related to activating the prefrontal lobe and the cingulate gyrus[34]. Mindfulness meditation brings a non-judgmental concentration on internal and external stimuli, and finally, a balanced mentality. Owing to the rapid spread of the epidemic, Wuhan was locked down on January 23, 2020. In the current situation, most patients with COVID-19 have a good prognosis[1,2], but fear remains[5-8,10-12]. In the present study, a 15-20 min mindfulness meditation was helpful for patients to foster positive emotions. This intervention can be performed together with the medical treatment of COVID-19. Mindfulness levels were significantly higher in the mindfulness intervention group than in the conventional group after the intervention, suggesting that the 15-20 min mindfulness meditation could effectively induce and enhance mindfulness in patients with COVID-19.

Anxiety and depression lead to sleep disorders, which, in turn, aggravate the negative emotions[38]. During the induction of the 5-min mindfulness meditation, the participants better controlled their emotions, cognitions, and behaviors. Davidson et al[39] reported that the left prefrontal cortex is significantly activated during meditation, and such activation is linked to the enhancement of positive emotions. Functional magnetic resonance imaging results suggested that mindfulness meditation can strengthen the insula's function, change the brain's circuit, and arouse more positive and optimistic feelings[13]. On the one hand, mindfulness meditation can guide the patients to focus on and get used to the current situation; on the other hand, it achieves a state of being mentally clear and emotionally calm, which improves sleep quality[40]. This study showed lower PSQI scores in the mindfulness group than in the conventional group after the intervention, indicating that an effective psychological intervention was as important as meditation in improving sleep quality.

At present, mindfulness-based stress reduction and MBCT can be combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy to provide a more definite psychological education about emotions, cognition, and functions[41]. In this study, the participants in both groups had high HADS scores before the intervention, indicating that the diagnosis and isolation influenced the psychological state of patients with COVID-19. After the 2-wk intervention, no significant difference in the HADS score was observed. Isolation and the cold environment of the hospital might play a role in this result, but it will have to be confirmed in future studies.

This study has some limitations. First, the participants were not randomized, and the assessors were not blinded. Second, the sample size was small, limiting the generalizability of the results. Additional studies are needed to address these issues.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, a 5-min mindfulness meditation audio induction can elevate the mindfulness levels, improve the sleep quality, and decrease the depression in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Furthermore, it is an effective, economical, and convenient non-drug psychological intervention that can be universally applied.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

At present, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is becoming a severe public health concern, especially in Wuhan (China), the most hit area of COVID-19 infection in China, which has set up and opened nine Fangcang Hospitals to treat patients with COVID-19. For patients with COVID-19, fear of the disease and negative emotions easily lead to a psychological crisis, and a timely and effective psychological intervention is of great significance.

Research motivation

Mindfulness meditation is beneficial to mitigate the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population, but no study examined such meditation in the COVID-19 patients themselves.

Research objectives

The survey explored the efficacy of mindfulness meditation in alleviating psychological distress and sleep disorders in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan Fangcang Hospital.

Research methods

This was a prospective study of patients with mild COVID-19 treated at Wuhan Fangcang Hospital in February 2020. The patients were voluntarily divided into either a mindfulness or a conventional group. The participants in both groups were treated with the same supportive therapy for COVID-19. Besides, the mindfulness group received mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, which contains a 5-min meditation.

Research results

After a 2-wk intervention, the mindfulness level (from 30.16 ± 5.58 to 35.23 ± 5.95, P < 0.001) and sleep quality (from 12.85 ± 3.06 to 9.44 ± 3.86, P < 0.001) significantly increased in the mindfulness group. However, there were no difference in the conventional group. After a 2-wk intervention, the mindfulness level (35.23 ± 5.95 vs 31.17 ± 6.50, P = 0.006) and sleep quality (9.44 ± 3.86 vs 11.87 ± 4.06, P = 0.011) were significantly increased in the mindfulness group than in the conventional group. Depression decreased in the mindfulness group (from 14.15 ± 3.21 to 12.50 ± 4.01, P = 0.038), but there was no difference between the two groups.

Research conclusions

The short-term mindfulness meditation can increase the mindfulness level, improve the sleep quality, and decrease the depression of patients with COVID-19.

Research perspectives

The short-term mindfulness meditation is very useful to patients with COVID-19, and long-term mindfulness meditation is worth further study as well.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the ethics review board of Jiangsu Province Hospital.

Clinical trial registration statement: This study is registered at the ethics committee of Jiangsu Provincial Hospital (No. 2020-SR-007). A separate document was uploaded as a proof of registry.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

CONSORT 2010 statement: The authors have read the CONSORT 2010 Statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CONSORT 2010 Statement.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: June 17, 2021

First decision: July 26, 2021

Article in press: December 7, 2021

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mukherjee M, Ssekandi AM S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang JJ

Contributor Information

Jing Li, Department of Geriatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Yun-Yun Zhang, Department of Geriatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Xiao-Yin Cong, Department of Psychology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Shu-Rong Ren, Department of Geriatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Xiao-Ming Tu, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 211166, Jiangsu Province, China.

Jin-Feng Wu, Department of Geriatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China. wujf64@163.com.

Data sharing statement

There are no additional data are available.

References

- 1.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA. 2020;324:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, Nair N, Mahajan S, Sehrawat TS, Bikdeli B, Ahluwalia N, Ausiello JC, Wan EY, Freedberg DE, Kirtane AJ, Parikh SA, Maurer MS, Nordvig AS, Accili D, Bathon JM, Mohan S, Bauer KA, Leon MB, Krumholz HM, Uriel N, Mehra MR, Elkind MSV, Stone GW, Schwartz A, Ho DD, Bilezikian JP, Landry DW. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1017–1032. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update-24 November 2020. [cited 20 May 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---24-november-2020 .

- 4.Zhou M, Cao G, Ming G. Research status and progress of human coronavirus. Intl J Lab Med. 2020;41:518–522. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peretti-Watel P, Alleaume C, Léger D, Beck F, Verger P COCONEL Group. Anxiety, depression and sleep problems: a second wave of COVID-19. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33:e100299. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu W, Wang C, Zou L, Guo Y, Lu Z, Yan S, Mao J. Psychological health, sleep quality, and coping styles to stress facing the COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:225. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00913-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sher L. COVID-19, anxiety, sleep disturbances and suicide. Sleep Med. 2020;70:124. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grover S, Dua D, Sahoo S, Mehra A, Nehra R, Chakrabarti S. Why all COVID-19 hospitals should have mental health professionals: The importance of mental health in a worldwide crisis! Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102147. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, Pollak TA, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P, Zandi MS, Lewis G, David AS. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:611–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.da Silva FCT, Neto MLR. Psychiatric symptomatology associated with depression, anxiety, distress, and insomnia in health professionals working in patients affected by COVID-19: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;104:110057. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang R, Yu X, Wang Q. Effect of mindfulness meditation induction combined with pelvic floor muscle training on postoperative patients with early cervical cancer. Lab Med Clin. 2020;17:35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rusch HL, Rosario M, Levison LM, Olivera A, Livingston WS, Wu T, Gill JM. The effect of mindfulness meditation on sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019;1445:5–16. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong H, Ni CX, Liu YZ, Zhang Y, Su WJ, Lian YJ, Peng W, Jiang CL. Mindfulness meditation for insomnia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychosom Res. 2016;89:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heckenberg RA, Eddy P, Kent S, Wright BJ. Do workplace-based mindfulness meditation programs improve physiological indices of stress? J Psychosom Res. 2018;114:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu Y. Research on the psychological mechanism of mindfulness de-automaticity and the effect of clinical intervention East China Normal University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.González-Valero G, Zurita-Ortega F, Ubago-Jiménez JL, Puertas-Molero P. Use of Meditation and Cognitive Behavioral Therapies for the Treatment of Stress, Depression and Anxiety in Students. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pascoe MC, Thompson DR, Jenkins ZM, Ski CF. Mindfulness mediates the physiological markers of stress: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:156–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong R, Cao X, Jiang Y. The implementation and effect of nursing human resource deployment plan in the emergency treatment of the new coronavirus infection. Chin Nursing Manag. 2020;20:226–229. [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Riet P, Levett-Jones T, Aquino-Russell C. The effectiveness of mindfulness meditation for nurses and nursing students: An integrated literature review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;65:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gauthier T, Meyer RM, Grefe D, Gold JI. An on-the-job mindfulness-based intervention for pediatric ICU nurses: a pilot. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Behan C. The benefits of meditation and mindfulness practices during times of crisis such as COVID-19. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37:256–258. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matiz A, Fabbro F, Paschetto A, Cantone D, Paolone AR, Crescentini C. Positive Impact of Mindfulness Meditation on Mental Health of Female Teachers during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiménez Ó, Sánchez-Sánchez LC, García-Montes JM. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Confinement and Its Relationship with Meditation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conversano C, Di Giuseppe M, Miccoli M, Ciacchini R, Gemignani A, Orrù G. Mindfulness, Age and Gender as Protective Factors Against Psychological Distress During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1900. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. COVID-19 Clinical management: living guidance. [cited 20 May 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19 .

- 28.Li Z. The content presentation method of psychological self-media: Taking the self-media content of Wu Zhihong and Li Songwei as examples. Youth Journalist . 2016;86 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fong TCT, Wan AHY, Wong VPY, Ho RTH. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-short form in cancer patients: a Bayesian structural equation modeling approach. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19:51. doi: 10.1186/s12955-021-01692-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q, Lin Y, Hu C, Xu Y, Zhou H, Yang L. The Chinese version of hospital anxiety and depression scale: Psychometric properties in Chinese cancer patients and their family caregivers. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;25:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai PS, Wang SY, Wang MY, Su CT, Yang TT, Huang CJ, Fang SC. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1943–1952. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-4346-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou X. Prevention and treatment of anxiety and fear in patients with the new coronavirus pneumonia. Med Pharm J Chin People's Liberation Army. 2020;32:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang W. Research on the compensation effect of mindfulness meditation on self-depletion of college students: Wuhan Sports University; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xue S. Characteristics of brain functional networks in different states: Dalian University of Technology; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steimer T. The biology of fear- and anxiety-related behaviors. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2002;4:231–249. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2002.4.3/tsteimer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adolphs R. The biology of fear. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R79–R93. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan Q, Jia K, Liu X. A six-week mindfulness training on aggressiveness and sleep quality of male long-term prisoners. Chin Mental Health J. 2015;29:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fang H, Tu S, Sheng J, Shao A. Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:2324–2332. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, Rosenkranz M, Muller D, Santorelli SF, Urbanowski F, Harrington A, Bonus K, Sheridan JF. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:564–570. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000077505.67574.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Black DS, O'Reilly GA, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Irwin MR. Mindfulness meditation and improvement in sleep quality and daytime impairment among older adults with sleep disturbances: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:494–501. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan D. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. Psychother Res. 2003;13:123–125. doi: 10.1080/713869628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no additional data are available.