Abstract

Objectives:

Women with substance use disorders have high unmet needs for HIV prevention and drug treatment and face challenges accessing care for other unique health issues, including their sexual and reproductive health.

Methods:

We did a cross-sectional evaluation of sexual and reproductive health behaviors and outcomes among women with substance use disorders, who were enrolled in one of two concurrent clinical trials of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. Descriptive analyses and bivariate logistic regression were used to assess factors driving contraceptive use, and other essential sexual and reproductive health services utilization and outcomes.

Results:

Among 226 women, 173 (76.5%) were of reproductive age. Most women had histories of unintended pregnancy (79.2%) or miscarriage (45.1%) and high HIV risk behaviors (53.5%). Most (61%) participants did not use any form of contraception at the time of assessment, although few (15%) reported pregnancy intentions. In bivariate models, ongoing criminal justice involvement was associated with 2.22 higher odds of not using contraception (95% confidence interval = 1.09–4.53; p = 0.03) and hazardous drinking was protective against not using contraception (odds ratio = 0.33, 95% confidence interval = 0.13–0.81; p = 0.02). Contraception use was not significantly associated with any other individual characteristics or need factors.

Conclusions:

This is the first study that identifies the unmet sexual and reproductive health needs of women with substance use disorders who are engaging with pre-exposure prophylaxis. We found that women accessed some health services but not in a way that holistically addresses the full scope of their needs. Integrated sexual and reproductive care should align women’s expressed sexual and reproductive health intentions with their behaviors and outcomes, by addressing social determinants of health.

Keywords: health outcomes, reproductive health, substance use, women

Introduction

An estimated 7.2 million women in the United States meet criteria for substance use disorders (SUDs). 1 Women with SUD experience disparate health outcomes and have more functional impairment compared to their male counterparts and have unique health needs.2–5 SUDs in women evolve more rapidly than in men with shorter time periods from initiation of drug use to addiction, 6 and are more often complicated by comorbid conditions, such as chronic pain 7 and psychiatric disorders.2,8,9

Many women use drugs with their sexual partners, 9 which increases the risk of HIV. In the United States, one in five new HIV infections annually are in women, and Black and Hispanic women are disproportionately affected. 10 Although most HIV infections among US women are directly attributable to heterosexual sex, 10 substance use (specifically, alcohol use) is associated with increased sexual risk-taking and decreased risk perception, even at non-abuse levels. 11 Opioid injecting is directly associated with increased HIV risk, particularly among women who often have overlapping sex and drug use partners. 12 Women with SUD are designated a high priority population for targeted evidence-based HIV prevention. 13 Within the HIV prevention armamentarium, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the only highly effective prevention strategy that is fully user-controlled, which is particularly powerful for women with SUD. 14 Yet PrEP remains highly under-scaled among women.

Treatment for SUD reduces overall morbidity and mortality, improves health-related quality of life, and is also effective HIV prevention. 15 Although women face a high burden of SUD, they are less likely to access SUD treatment programs than men.16–18 Women’s engagement in drug treatment may be complicated by relationship power dynamics and the real or perceived threat of intimate partner violence (IPV) or jeopardizing the intimate relationship.19–22 Women’s SUD and their enrollment in treatment also more broadly impacts their families, social structures, and economic conditions,6,9,23 since women’s disclosure of substance use may result in threats to their parental rights. 24 Women have higher rates of trauma and co-occurring mental health needs that contribute to their SUD and complicate access to and retention in treatment.18,25 Despite these many potential barriers, once in treatment, women attain parity to men in terms of health outcomes.25,26

Women with SUD face similar barriers to accessing care for other unique health issues, including for their sexual and reproductive health (SRH). According to the Guttmacher Commission and the World Health Organization, essential SRH services include “a choice of safe and effective contraceptive method”; “safe and effective abortion services and care”; and “prevention, detection, and treatment of sexually transmitted infections including HIV and reproductive cancers.” 27 Women with SUD are often stigmatized, lack the social capital and power to assert their right to reproductive autonomy, and may be overtly coerced or pressured into decisions on their SRH. 28 Prior research has shown that women with SUD face disproportionately high rates of unintended pregnancies,29–31 and subsequent pregnancy terminations, 32 as well as lower rates of contraception use, 33 which may be proxies for limited access to reproductive care or degree of reproductive control. High rates of sexually transmitted infections34–36 and abnormal Pap tests37–39 exemplify SRH burdens experienced by women with SUD.

We recently conducted a systematic review of pregnancy planning and termination needs among women with SUD who were involved in criminal justice systems (WICJ). We found that WICJ often underutilize contraception despite expressing an interest in not becoming pregnant and have limited access to SRH services. 40 Although there are emerging data to suggest need, few interventions have addressed the unique SRH needs of women with SUD. 40 We aim to further this work by systematically evaluating the SRH needs of women with SUD to inform interventions that are specifically and meaningfully tailored to this population of women. To our knowledge, this is the first study that identifies the profound SRH needs of community-based women with SUDs who are engaging with PrEP. This area of study is designed to inform the development of integrated HIV prevention and pregnancy planning programs, given the dearth of currently available technology to simultaneously prevent both HIV and pregnancy (known as multi-purpose prevention or dual-prevention technology.)

Methods

We analyzed data from two concurrent clinical trials on PrEP for women, which recruited participants from either community-based criminal justice (CJ) settings or drug treatment settings. Both studies were based in a mid-sized city in New England with inclusion criteria for each detailed below. Because both studies enrolled women with SUD at high risk of HIV infection, this combined dataset allowed us to evaluate the SRH needs of two overlapping populations of women with SUD in need of HIV prevention.

EMPOWERING was a PrEP demonstration project that screened WICJ and members of their risk networks for PrEP eligibility and started PrEP for those meeting eligibility criteria (NCT03293290 at Clinicaltrials.gov). Study procedures have been described elsewhere. 41 The primary outcome for the study, on which study power and sample size were calculated, was feasibility and acceptability of PrEP outreach, initiation, and delivery. Briefly, women were recruited from advertisements in probation and parole offices, community outreach programs, courts, drug treatment centers, halfway houses, and area health centers. Participants were also peer-referred using modified respondent-driven sampling.

Participants were eligible for enrollment if they (1) were ⩾18 years old; (2) identified as female; (3) were self-reported HIV-uninfected; (4) were recently involved in the CJ system (released from prison or jail in the past 6 months or were on probation/parole); and (5) were currently residing in the area. All enrolled participants had an SUD (and are therefore included in the present analysis), although having an SUD was not a specific inclusion criterion for the clinical trial. Potential participants were excluded if they were unable or unwilling to provide informed consent. Potential participants could also be excluded if they were threatening to staff, defined as showing an intention to cause bodily harm—no potential participants were excluded for this reason. Study procedures were approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board (IRB) (HIC #1606017882) and Research Advisory Committees from the Connecticut statewide Department of Corrections and the Court Support Services Division. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants completed a baseline interview in a private setting by a trained research assistant in English or Spanish using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture)42,43 hosted at Yale University. The baseline interview took approximately 1–1.5 h to complete, and participants were compensated US$20 for their time. For clarity, hereafter, we refer to EMPOWERING by recruitment source, as “CJ settings.”

OPTIONS developed and tested the effect of a patient-centered HIV prevention decision aid on PrEP uptake among women in SUD treatment (NCT03651453 at Clinicaltrials.gov). Study procedures 44 and qualitative findings24,45 have been described elsewhere. The primary outcomes, on which the study power and sample size were calculated, were effects of the decision aid, as compared to enhanced standard of care, on decisional preference for PrEP, HIV risk estimation, and longitudinal PrEP uptake. Briefly, women with SUDs were recruited onsite at the area’s largest drug treatment program, which includes a comprehensive array of programs across four sites with an open access policy, such as primary care, ambulatory and residential treatment, and medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD). Program staff also referred potential participants through a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) secure Qualtrics link (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and a private protected phone line.

Participants were eligible for enrollment if they (1) were ⩾18 years old; (2) identified as female; (3) were self-reported HIV-uninfected; and (4) were receiving any form of SUD treatment at our partnering site. We did not pre-specify type of SUD in terms of substance use, although most participants had opioid use disorder and were receiving MOUD. They were excluded if they were unable or unwilling to provide informed consent. Study procedures were approved by the Yale University IRB (HIC #2000021561) and the Operations Management Team at the partnering drug treatment agency, APT Foundation, Inc. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. A trained research assistant completed a baseline interview through REDCap42,43 at APT Foundation, Inc. in a private setting in English or Spanish, and participants were compensated US$20 for their time. Hereafter, we refer to OPTIONS by recruitment source, as “drug treatment settings.”

Materials and survey

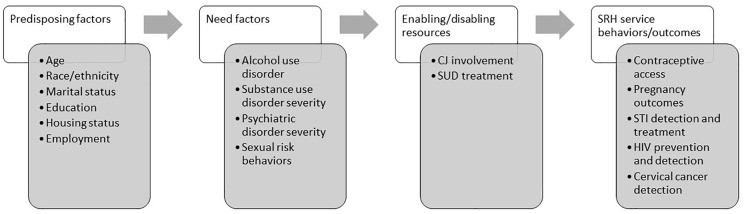

Applying the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Figure 1),46–48 we developed a brief survey to evaluate women’s SRH service behaviors and outcomes (Supplementary File). The instrument was developed, using the theoretical construct domains as described, by internal consensus among a group of experts in infectious diseases and women’s health. The SRH instrument was incorporated into the baseline interview for both study protocols. The theoretical model conceptualizes that health behaviors, and ultimately health outcomes, are driven by the predisposing characteristics of the individual, need factors, and enabling or disabling resources. The model presents a useful way to describe and organize factors potentially driving health behaviors.

Figure 1.

Measures organized by the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations.

CJ: criminal justice; SUD: substance use disorder; STI: sexually transmitted infection.

The main SRH outcome of interest was current contraceptive use, including: surgical (tubal ligation, hysterectomy, and oophorectomy), long-active reversible contraceptive (LARC; implants, intrauterine devices (IUDs)), injectables (Depo Provera), hormonal (pill, patch, and ring), barrier (condom, diaphragm, and sponge), natural (pulling out, rhythm method, and abstinence), or none/not applicable. Current contraceptive use was analyzed descriptively and dichotomized as any versus none/natural. We separately evaluated contraceptive access by asking, “Have you ever had trouble accessing birth control?” and “What were the main factor(s) for having trouble accessing birth control?” Other essential SRH outcomes of interest based on the Guttmacher Commission designation 27 were the following: (1) pregnancy outcomes in terms of lifetime number of pregnancies; age at first pregnancy, which was examined both as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable based on teenage pregnancy (prior to age of 20); ever having had an unplanned pregnancy (dichotomous); ever being unable to become pregnant when desired (self-reported infertility); and ever having had spontaneous or induced pregnancy termination(s); (2) recent sexually transmitted infection (STI) detection and treatment in terms of having any STI in the past 6 months; (3) HIV prevention and detection in terms of receipt of an HIV test within the past year per CDC guidelines; 49 and (4) cervical cancer screening was assessed in terms of receipt of a Pap test in the past 3 years. 50 All SRH outcomes were self-reported.

Other measures were also intentionally harmonized across the two studies because they were conducted by the same investigative team and the clinical trials were ongoing concurrently. Individual characteristics measured at the baseline interview were age, race, ethnicity, education, housing status, and employment pattern. Housing status was categorized as stable (if residing alone, with sex partner and/or children), temporary (couch-surfing or doubling up if residing with family, friends, or parents), or homeless, defined as residing in a place not meant for human habitation, shelter, or if usual living arrangements were “in a controlled environment.”

SUD type and severity were measured at baseline for drug treatment settings and at Month 3 follow-up for CJ settings. The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Tool (AUDIT) was used to measure hazardous alcohol use and alcohol dependence and was dichotomized at 4, which is sensitive for detecting unhealthy alcohol use in women. 51 We used the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) to assess lifetime severity in terms of impact on functioning across multiple domains (medical, psychiatric, employment, legal, drug use, alcohol use, and family/social). Psychiatric domains were measured at baseline in both studies; substance use domains were measured at baseline for drug treatment settings and at Month 3 follow-up for CJ settings. Scores are calculated on a scale from 0 to 1 with higher scores indicating more severe impairment.52,53 Prior validated cut-offs were used to define severe psychiatric disorders (ASI ⩾ 0.22), severe alcohol use disorders (ASI ⩾ 0.17), and severe SUDs (ASI ⩾ 0.12) aligning with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria.54,55 Sexual risk was evaluated at baseline in terms of past 6-month behaviors, including condomless sex, number of partners, and ever exchanging sex for money, drugs, food, or shelter ever (i.e. transactional sex). HIV risk was defined in terms of the Denver HIV risk scale. 56 HIV risk was dichotomized in terms of PrEP eligibility as per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) clinical guidelines. 57

Enabling or disabling resources included current CJ involvement, defined as having been incarcerated in jail in the past 30 days or currently on probation, parole, or intensive pretrial supervision.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was restricted to participants from either study who had data available on contraceptive choice. Of the 234 HIV-negative women with SUD enrolled across the two clinical trials, 226 women had data available on contraception and were included in the overall descriptive analysis. All categorical variables were analyzed descriptively for frequency. All continuous variables were checked for normal distribution using data visualization with QQ plots and histograms and described by mean (±SD) if normally distributed or median (interquartile range (IQR), range) if non-normally distributed. We compared participants who were and were not currently using any form of contraception in terms of individual characteristics, need factors, enabling/disabling resources, and other SRH service utilization and outcomes, using chi-square and Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate, for categorical variables and independent t-tests or Mann–Whitney U non-parametric tests for continuous variables as needed. We also compared participants in terms of these same factors by study enrollment.

A sub-sample of 173 participants of reproductive age (18–44 years old) was included in modeling current contraceptive use. We modeled associations between “no contraception” and individual characteristics, need factors, enabling/disabling resources, and other SRH behaviors, using bivariate logistic regression to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Exploratory multivariate models were generated using logistic regression, including covariates of interest with statistical and clinical significance. Exploratory bivariate models of each type of contraceptive use were generated, including covariates of interest with statistical and clinical significance. Data analysis was generated using SAS software, Version 9.5 of the SAS System (Copyright © 2016 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Table 1 depicts baseline characteristics of the study sample overall and by current contraception use, organized by the Behavioral Health Model. Participants had a mean age of 40.3 years (SD = 10.1) and 76.6% of the sample was of reproductive age. Most participants were non-Hispanic white, reflective of the demographic profile of women with SUD in treatment, both regionally and nationally. 5 Nearly half of all participants were high school graduates (47.4%) who were stably housed (54.4%) and employed full-time (40.8%). There were no statistically significant differences in contraceptive use in terms of any individual characteristics. There were differences between the two study samples in terms of housing and employment, with CJ setting participants more often experiencing unstable housing and unemployment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study sample, by current contraception use.

| Total (N = 226) a | No current contraception (N = 138) | Contraception use (N = 88) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study participation | ||||||

| CJ settings | 64 (28.3) | 41 (29.7) | 23 (26.1) | 0.56 | ||

| Drug treatment settings | 162 (71.7) | 97 (70.3) | 65 (73.9) | |||

| Individual characteristics | ||||||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 40.3 (10.1) | 40.4 (10.4) | 40.1 (9.7) | 0.83 | ||

| Reproductive age, n (%) | 173 (76.6) | 102 (73.9) | 71 (80.7) | 0.24 | ||

| Race, n (%) | n = 205 | n = 126 | n = 79 | 0.96 | ||

| White | 157 (76.6) | 96 (76.2) | 61 (77.2) | |||

| Black | 42 (20.5) | 26 (20.6) | 16 (20.3) | |||

| Other | 6 (2.9) | 4 (3.2) | 2 (2.5) | |||

| Hispanic ethnicity, n (%) | 26 (11.5) | 15 (10.9) | 11 (12.5) | 0.71 | ||

| Education, n (%) | 0.90 | |||||

| Less than HS | 42 (18.6) | 25 (18.1) | 17 (19.3) | |||

| HS graduate | 107 (47.4) | 67 (48.6) | 40 (45.5) | |||

| Higher education | 77 (34.1) | 46 (33.3) | 31 (35.2) | |||

| Housing status, n (%) | 0.53 | |||||

| Stable | 123 (54.4) | 71 (51.5) | 52 (59.1) | |||

| Temporary | 61 (27.0) | 40 (29.0) | 21 (23.9) | |||

| Homeless | 42 (18.6) | 27 (19.6) | 15 (17.1) | |||

| Employment, n (%) | 0.50 | |||||

| Full-time | 89 (40.8) | 58 (43.9) | 31 (36.1) | |||

| Part-time | 46 (21.1) | 27 (20.5) | 19 (22.1) | |||

| Retired/disability | 21 (9.6) | 10 (7.6) | 11 (12.8) | |||

| Unemployed | 62 (28.4) | 37 (28.0) | 25 (29.1) | |||

| Need factors | ||||||

| Hazardous drinking, n (%) | n = 107; 55 (51.4) | n = 69; 29 (42.0) | n = 38; 26 (68.4) | 0.01 | ||

| Severe alcohol use disorder, n (%) | n = 34; 15 (44.1) | n = 20; 9 (45.0) | n = 14; 6 (42.9) | 0.90 | ||

| Severe SUD, n (%) | n = 94; 93 (98.9) | n = 56; 55 (98.2) | n = 38; 38 (100.0) | 0.41 | ||

| Severe psychiatric disorder, n (%) | n = 182; 146 (80.2) | n = 113; 91 (80.5) | n = 69; 55 (79.7) | 0.89 | ||

| Sexually active in past 6 months, n (%) | 175 (77.4) | 112 (81.2) | 63 (71.6) | 0.09 | ||

| Median number of sexual partners in past 6 months (IQR, range) | 1.0 (1.0, 0–59) | 1.0 (1.0, 0–50) | 1.0 (2.0, 1–50) | 0.15 | ||

| Condomless sex in past 6 months, n (%) | 168 (79.3) | 106 (80.9) | 62 (76.5) | 0.45 | ||

| Ever exchanged sex, n (%) | 92 (41.1) | 55 (40.4) | 37 (42.1) | 0.81 | ||

| HIV risk, n (%) | 0.61 | |||||

| High/medium | 121 (53.5) | 72 (52.2) | 49 (55.7) | |||

| Low/no | 105 (46.5) | 66 (47.8) | 39 (44.3) | |||

| Enabling/disabling resources | ||||||

| Any current CJ involvement, n (%) | 60 (26.6) | 42 (30.4) | 18 (20.5) | 0.10 | ||

| Jailed in past 30 days, n (%) | 11 (4.9) | 9 (6.5) | 2 (2.3) | 0.15 | ||

| On probation or parole, n (%) | n = 177; 56 (31.6) | n = 109; 39 (35.8) | n = 68; 17 (25.0) | 0.13 | ||

| SRH service utilization and outcomes | ||||||

| Current contraception, n (%) | ||||||

| Natural/none | 138 (61) | |||||

| Surgical | 43 (19) | n/a | ||||

| LARC | 20 (9) | |||||

| Barrier | 9 (4) | |||||

| Injectables | 9 (4) | |||||

| Hormonal | 7 (3) | |||||

| Ever had trouble accessing birth control, n (%) | 15 (6.6) | 8 (5.8) | 7 (8.0) | 0.53 | ||

| Mean number of pregnancies (SD) | 3.6 (2.7) | 3.3 (2.4) | 4.0 (3.0) | 0.05 | ||

| Mean age at first pregnancy (SD) | 18.8 (4.9) | 18.7 (5.2) | 18.9 (4.7) | 0.75 | ||

| Pregnant as teenager, n (%) | 131 (64.9) | 79 (64.8) | 52 (65.0) | 0.92 | ||

| Ever had unplanned pregnancy, n (%) | 179 (79.2) | 110 (79.7) | 69 (78.4) | 0.81 | ||

| Interested in becoming pregnant, n (%) | 34 (15.0) | 25 (18.1) | 9 (10.2) | 0.11 | ||

| Self-reported infertility, n (%) | 49 (21.7) | 30 (21.7) | 19 (21.6) | 0.98 | ||

| Ever miscarried, n (%) | 102 (45.1) | 65 (47.1) | 37 (42.1) | 0.46 | ||

| Median number of miscarriages (IQR, range) | 1.0 (1.0, 0–6) | 1.0 (1.0, 0–6) | 1.0 (1.0, 1–6) | 0.25 | ||

| Ever terminated pregnancy, n (%) | 103 (45.6) | 65 (47.1) | 38 (43.2) | 0.56 | ||

| Median number of pregnancies terminated (IQR, range) | 2.0 (1.0, 1–10) | 2.0 (1.0, 1–5) | 2.0 (1.0, 1–10) | 0.50 | ||

| STI in past 6 months, n (%) | 7 (3.1) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (3.4) | 0.93 | ||

| Tested for HIV in past 12 months, n (%) | 162 (71.7) | 99 (71.7) | 63 (71.6) | 0.98 | ||

| Received Pap test in past 3 years, n (%) | 168 (75) | 104 (77.6) | 62 (70.5) | 0.23 | ||

| Location of last Pap test, n (%) | 0.80 | |||||

| Gynecology office | 122 (54.2) | 76 (55.5) | 46 (52.3) | |||

| Primary care office | 29 (12.9) | 15 (11.0) | 14 (15.9) | |||

| Planned Parenthood | 42 (18.9) | 27 (19.7) | 15 (17.1) | |||

| Prison/jail | 22 (9.7) | 14 (10.2) | 8 (9.1) | |||

| Other | 10 (4.4) | 5 (3.6) | 5 (5.7) | |||

CJ: criminal justice; SD: standard deviation; HS: high school; SUD: substance use disorder; IQR: interquartile range; SRH: sexual and reproductive health; LARC: long-active reversible contraceptive; STI: sexually transmitted infection.

Unless otherwise shown.

In terms of women’s current contraceptive methods, most (61%) participants did not use any form of contraception at the time of assessment. Among the remaining 39% who did report current contraceptive use, 19% used surgical methods, 11% had female-controlled methods that included hormonal contraception (7%) or barrier methods (4%), and the remaining 9% used LARCs.

When we examined need factors driving SRH behaviors and outcomes (Table 1), we found over half of participants met criteria for hazardous drinking, most (98.9%) had a severe SUD, and 80.2% had severe psychiatric disorders. Women reported engaging in high rates of condomless sex (79.3%) with a median 1.0 sexual partners (IQR = 1.0, range= 1–59) in the past 6 months and high rates of lifetime engagement in transactional sex (41.1%). These factors resulted in over half of the sample (53.5%) experiencing high HIV risk that would meet clinical criteria for PrEP.

Hazardous drinking was significantly more prevalent in participants reporting current contraceptive use (68% versus 42%, p = 0.01), but there were otherwise no significant differences in need factors by contraceptive use (Table 1). There were also no significant differences in substance use need factors by study enrollment. Women in drug treatment settings were significantly more likely to meet criteria for a severe psychiatric disorder (75.3% versus 24.7%, p < 0.001).

Approximately one-third of all study participants had any ongoing CJ involvement, but there were no differences in CJ involvement by contraceptive use (Table 1). More information on the nature of CJ involvement and charged offenses was not available for all study participants. As anticipated because of inclusion criteria, more CJ setting participants were on probation or parole compared to drug treatment setting participants.

Although 61% of participants were not using any contraception, few (6.6%) reported difficulty accessing it (Table 1). Overall, most participants reported teenage pregnancy (64.9%), unintended pregnancies (79.2%), and spontaneous (45.1%) and induced pregnancy terminations (45.6%), at similar rates reported in other populations with SUD. 58 There were no differences in these SRH outcomes by current contraceptive choice. Most (75%) participants reported having received Pap testing in the past 3 years and HIV testing in the past year (71.7%), with no differences by current contraceptive use.

When SRH outcomes were compared by study participation, CJ setting participants did have a younger mean age at first pregnancy (16.8 vs 19.3 years, p = 0.03) and higher frequency of STI in the last 6 months (6.7% vs 2.4%, p < 0.001). There was no difference in receipt of Pap testing by study participation, although participants varied in where they received their last Pap test, with the largest proportion of CJ setting participants going to planned parenthood (31.3%) while most drug treatment participants attended a gynecologist’s office or clinic (67.5%).

Among the sub-sample of participants of reproductive age, in bivariate models, any current CJ involvement was associated with 2.22 higher odds of not using contraception (95% CI = 1.09–4.53; p = 0.03; Table 2). In exploratory multivariate models, CJ involvement remained a significant correlate of lack of contraceptive use even after controlling for lifetime addiction severity, lifetime psychiatric severity, and pregnancy interest, but the association was diminished after controlling for race. Hazardous drinking was protective against “no contraceptive use” (OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.13–0.81; p = 0.02). There were no significant differences in hazardous drinking by age, race, ethnicity, employment, or housing status, but hazardous drinking was more frequent in women without CJ involvement compared to WICJ (30.3% vs 18%, p = 0.001), perhaps because recent incarceration was temporarily protective against alcohol use. In an exploratory multivariate model of not using contraception, CJ involvement remained significant even after controlling for hazardous drinking (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 9.42, 95% CI = 2.2–40.3; p = 0.003). In exploratory bivariate models of different types of contraceptive choices (long-acting contraception (e.g. LARC, sterilization), user-dependent contraception (e.g. oral contraceptive pills, vaginal rings, contraceptive injection), and no contraceptive methods, there were no significant correlations with any need or SRH service utilization factors (data not shown).

Table 2.

Bivariate correlates of no contraception use among participants of reproductive age (N = 173).

| No contraception OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| CJ setting study participants | 1.35 (0.68, 2.65) | 0.39 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | 0.51 |

| Race | 0.84 | |

| White | 1 | |

| Black | 0.79 (0.33, 1.91) | |

| Other | 1.34 (0.12, 15.19) | |

| Hispanic | 0.97 (0.41, 2.33) | 0.95 |

| Education | 0.55 | |

| Less than HS | 1 | |

| HS degree | 1.57 (0.68, 3.62) | |

| Higher education | 1.28 (0.53, 3.05) | |

| Housing status | 0.16 | |

| Stable | 1 | |

| Temporary | 1.63 (0.79, 3.39) | |

| Homeless | 2.07 (0.89, 4.82) | |

| Employment | 0.90 | |

| Full-time | 1 | |

| Part-time | 0.75 (0.34, 1.65) | |

| Retired/disability | 0.86 (0.25, 2.98) | |

| Unemployed | 0.81 (0.38, 1.74) | |

| Hazardous drinking | 0.33 (0.13, 0.81) | 0.02 |

| Severe alcohol use disorder | 0.60 (0.12, 2.97) | 0.53 |

| Lifetime psychiatric severity | 0.97 (0.42–2.26) | 0.94 |

| Condomless sex past 6 months | 1.11 (0.46, 2.68) | 0.81 |

| High HIV risk | 0.79 (0.43, 1.47) | 0.46 |

| Current CJ involvement | 2.22 (1.09, 4.53) | 0.03 |

| Trouble accessing birth control | 0.78 (0.27, 2.25) | 0.64 |

| Teenage pregnancy | 0.87 (0.40, 1.85) | 0.71 |

| Unplanned pregnancy | 1.27 (0.60, 2.68) | 0.53 |

| Interested in becoming pregnant | 2.12 (0.92, 4.89) | 0.08 |

| STI past 6 months | 1.39 (0.25, 7.81) | 0.71 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; CJ: criminal justice; HS: high school; STI: sexually transmitted infection.

Discussion

Women with SUDs experience high needs for concurrent SUD treatment and PrEP for HIV prevention. In the present analysis, we build on this finding to evaluate SRH service engagement and outcomes among women with SUDs enrolled in PrEP clinical trials. Most women had histories of unintended pregnancy (79.2%), high HIV risk behaviors (53.5%), and miscarriage (45.1%). To our knowledge, this is the first study that identifies the profound unmet SRH needs of women with SUDs who are engaging with PrEP.

Women with SUDs in CJ and drug treatment settings often have overlapping barriers to care engagement. But by disaggregating data, we were able to evaluate important differences in SRH outcomes between women with SUDs engaging in PrEP clinical trials from CJ and drug treatment settings. These findings have important implications for how to address women’s family planning and HIV prevention needs effectively and simultaneously in each of these key settings.

Our study demonstrates a population of women with significant SRH histories beginning at young ages, as nearly two-thirds of our participants reported pregnancies prior to the age of 20. We also observed important associations between contraceptive use and CJ involvement among women who were of reproductive age. In bivariate models, current CJ involvement was associated with twice the odds of not using contraception. Current CJ involvement may be a marker of socioeconomic marginalization and disempowerment that disenfranchises women from health care.

Alternatively, lack of contraceptive use may be related to prior negative health outcomes and healthcare experiences that are common to WICJ. Similar to the only extant study on SRH in community-based WICJ, we found that roughly half of women surveyed had histories of spontaneous and induced pregnancy terminations. 58 Miscarriages, especially when repetitive, are associated with serious physical and mental health consequences that compound other health disparities. 59 More than three-quarters of participants reported a history of unplanned pregnancy. Unplanned pregnancies are not necessarily undesired and pregnancy terminations are not necessarily adverse health outcomes if women have autonomy to make these choices. However, women with SUDs often lack the social capital and power to do so and may be overtly coerced or pressured into SRH decisions. This is evidenced from historic efforts of forced sterilization in people with SUDs and the offering cash of incentives for women with SUDs to use LARC methods.28,60 Throughout a history of coercive intervention, Black women have been disproportionately affected. 61 Though most women in our study were not using contraception, those who were most commonly reported using surgical methods or LARC. These methods are highly effective at preventing pregnancy, but they are also long-acting if not permanent and are thus a potential tool for reproductive coercion. Surgical methods and LARC should be offered to women alongside a full array of potential options so women can make informed and personal choices. 62

Despite high rates of past unplanned pregnancies, less than half of women in our sample were using contraception at the time of assessment. This is notably lower than current CDC estimates that 65% of the general population of reproductive-aged women across the United States uses contraception. 63 These findings are consistent with literature showing lower rates of contraceptive use and higher rates of unintended pregnancies among WICJ37,58,64–67 and other women with SUDs.29–31,33 While only 15% of participants reported interest in becoming pregnant, more than three-quarters reported being sexually active in the last 6 months and nearly all sexually active women reported condomless sex. There was no significant difference in contraceptive use based on interest in becoming pregnant, and yet most women in our study said they could readily access contraception, so it remains to be understood why they were not using it. Our findings confirm that women’s pregnancy intentions misalign with their actual health behaviors.

The high number of competing concerns among women with SUD at risk of HIV could contribute to the low rates of contraceptive use, since comprehensive SRH healthcare may be seen as a less pressing priority than basic subsistence needs—for both women and their healthcare providers. 68 For example, our participants reported high rates of unstable housing (45.6%), unemployment (28.4%), severe SUDs (99%), and severe psychiatric disorders (64.6%) that may take precedence over SRH prevention and care. Gaps in SRH services during incarceration may contribute to low levels of contraceptive use following return to communities. One study of CJ healthcare providers found that contraception is “not high on the care needs in a large jail” due to financial and structural constraints. 69 Without attentive SRH preventive care that supports women’s reproductive needs and choices, HIV infection, STIs, and pregnancies may further compound socioeconomic, interpersonal, and psychiatric morbidity and contribute to health disparities. These reproductive health outcomes are tied not only to risk behaviors (i.e. condomless sex, sex under the influence of substances, partner coercion), but also to structural, interpersonal, and sociocultural circumstances, such as nutrition, substance use, and IPV exposure.70,71 Dasgupta et al. 58 analyzed SRH concerns among women with SUDs with a pregnancy history in community corrections settings and established a link between experiences of IPV and increased rates of spontaneous and induced pregnancy terminations.

Despite the discordance between contraception use and expressed pregnancy intentions and desires, we were surprised to find that 75% of women reported receiving a Pap test in the last 3 years and 71.7% of women reported being tested for HIV in the 12 months prior to study enrollment. These data suggest that SRH care is siloed for this population of women, with cervical cancer and HIV testing separated from family planning. However, prior studies have shown that 20%–40% of WICJ37,38,72 and up to 44% of women with SUDs 39 report a history of an abnormal Pap test that would warrant more frequent screening and follow-up. By assessing Pap test receipt within the past 3 years, we may have overestimated the proportion of women who are up to date with cervical cancer prevention. We nonetheless demonstrate women accessing one type of SRH care but not another. Comprehensive SRH care is an area that demands future attention and SRH services should be better integrated into both CJ and SUD treatment settings, building on the successes we found in terms of pap testing, to include family planning.

Our results also demonstrate the need for integrated HIV/STI prevention with SRH care for women at risk of HIV. In a sample where more than half of the women are at risk of HIV and nearly two-thirds of the women express discordant reproductive health wishes and contraception use, dual-prevention technology is desperately needed. Prior studies have linked STI incidence and unplanned pregnancy in WICJ, but condoms remain the only dual-prevention strategy currently available. 64 Condoms are only moderately effective at pregnancy prevention (13% of women who exclusively use condoms will become pregnant in 1 year 73 ), are a user-dependent method, and negotiating condom use with male partners is fraught with challenges, including precipitation of IPV.19,74–77 As a consequence, consistent condom use rarely occurs, as demonstrated in our study where nearly all women reported condomless sex in the past 6 months. In the wake of recent advances in HIV prevention (including PrEP), our results call for technology that integrates pregnancy and HIV prevention into non-user-dependent methods, such as combined contraceptive and PrEP injectables/vaginal rings. If these methods are to be adopted, they must be bolstered by empowerment interventions that address both pregnancy planning and HIV prevention choices for populations at high risk of negative SRH outcomes.

Our study has some important limitations. All data were self-reported and could have been limited by bias that underestimates socially undesirable outcomes, such as history of unintended pregnancy, therapeutic abortions, or lack of contraception use. We accessed women through HIV prevention studies, which may have resulted in a selection bias against women who are not currently engaging with any systems of care or supervision and therefore could be at even higher risk of negative SRH outcomes. Studies were not intentionally powered for SRH outcomes, so limited sample size for some outcomes may have contributed to challenges developing stable multivariate models. Our data are cross-sectional and thus cannot assess causality nor timing of when some SRH outcomes occurred. In this study setting, participants had access to social services and Medicaid through expansion, which may limit generalizability to other states with more limited resources. Some potential confounders (including IPV) were un-measured and others (including substance use severity) were not available for all participants. These limitations notwithstanding, findings have important implications for the next generation of comprehensive and integrated SRH care.

Conclusion

We found that women are engaging in some SRH services, but this care does not holistically address the full scope of their SRH needs. Integrated SRH care in both CJ and community settings may be effective in aligning women’s expressed SRH intentions with their SRH behaviors and outcomes. Future research should use clinical data in addition to self-report to assess women’s SRH utilization, alongside qualitative data to better understand women’s experiences navigating barriers to holistic SRH care. Future interventions that combine HIV and pregnancy prevention for women with SUDs should address social determinants of health. Women with SUD in need of HIV prevention strategies are similarly at risk of a host of specific SRH outcomes, including contraception underutilization and unintended pregnancy.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455065211070543 for Overlapping needs for sexual and reproductive health and HIV prevention in women with substance use disorders by Britton Gibson, Emily Hoff, Alissa Haas, Zoe M Adams, Carolina R Price, Dawn Goddard-Eckrich, Sangini S Sheth, Anindita Dasgupta and Jaimie P Meyer in Women’s Health

Footnotes

Authors’ note: Alissa Haas and Jaimie Meyer is now affiliated to Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT, USA.

Author contribution(s): Britton Gibson: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Emily Hoff: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Alissa Haas: Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Zoe Adams: Conceptualization; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Carolina R, Price: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Project administration; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Dawn Goddard-Eckrich: Conceptualization; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Sangini Sheth: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Anindita Dasgupta: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Jaimie Meyer: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research support provided by Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Development Award (to J.P.M.) and Gilead Sciences Investigator Sponsored Award (to J.P.M.). Funding sources played no role in data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

ORCID iDs: Britton Gibson  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0058-4272

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0058-4272

Sangini S Sheth  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3154-9624

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3154-9624

Jaimie P Meyer  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5735-385X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5735-385X

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2018 national survey on drug use and health: women. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Back SE, Payne RL, Wahlquist AH, et al. Comparative profiles of men and women with opioid dependence: results from a national multisite effectiveness trial. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2011; 37(5): 313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hernandez-Avila CA, Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR. Opioid-, cannabis- and alcohol-dependent women show more rapid progression to substance abuse treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend 2004; 74: 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Darke S, Ross J, Teesson M, et al. Health service utilization and benzodiazepine use among heroin users: findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS). Addiction 2003; 98(8): 1129–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. TIP 51: addressing the specific needs of women (Treatment Improvement Protocol). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Back SE, Lawson KM, Singleton LM, et al. Characteristics and correlates of men and women with prescription opioid dependence. Addict Behav 2011; 36(8): 829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jamison RN, Butler SF, Budman SH, et al. Gender differences in risk factors for aberrant prescription opioid use. J Pain 2010; 11(4): 312–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koons AL, Rayl Greenberg M, Cannon RD, et al. Women and the experience of pain and opioid use disorder: a literature-based commentary. Clin Ther 2018; 40(2): 190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Campbell ANC, Barbosa-Leiker C, Hatch-Maillette M, et al. Gender differences in demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with opioid use disorder entering a comparative effectiveness medication trial. Am J Addict 2018; 27(6): 465–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New HIV diagnoses among women in the US and dependent areas in 2017. HIV and women. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seth P, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, et al. Alcohol use as a marker for risky sexual behaviors and biologically confirmed sexually transmitted infections among young adult African-American women. Women’s Health Issues 2011; 21(2): 130–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. El-Bassel N, Terlikbaeva A, Pinkham S. HIV and women who use drugs: double neglect, double risk. Lancet 2010; 376: 312–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. The White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States: updated to 2020. July 2015. ed. Washington, DC: The White House Office of National AIDS Policy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sheth AN, Rolle CP, Gandhi M. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for women. J Virus Erad 2016; 2: 149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Springer SA, Larney S, Alam-Mehrjerdi Z, et al. Drug treatment as HIV prevention among women and girls who inject drugs from a global perspective: progress, gaps, and future directions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 69(Suppl. 2): S155–S161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mahmood ST, Vaughn MG, Mancini M, et al. Gender disparity in utilization rates of substance abuse services among female ex-offenders: a population-based analysis. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2013; 39(5): 332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007; 86: 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, et al. Substance abuse in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2010; 33: 339–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. J Womens Health 2011; 20(7): 991–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Greenfield SF, Grella C. Alcohol & drug abuse: what is “women-focused” treatment for substance use disorders? Psychiatr Serv 2009; 60: 880–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McHugh RK, Votaw VR, Sugarman DE, et al. Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders. Clin Psychol Rev 2018; 66: 12–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gilchrist G, Dennis F, Radcliffe P, et al. The interplay between substance use and intimate partner violence perpetration: a meta-ethnography. Int J Drug Policy 2019; 65: 8–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McHugh RK, Devito EE, Dodd D, et al. Gender differences in a clinical trial for prescription opioid dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat 2013; 45(1): 38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Qin Y, Price C, Rutledge R, et al. Women’s decision-making about PrEP for HIV prevention in drug treatment contexts. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2020; 19: 2325958219900091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choi S, Adams SM, Morse SA, et al. Gender differences in treatment retention among individuals with co-occurring substance abuse and mental health disorders. Subst Use Misuse 2015; 50(5): 653–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Messina N, Burdon W, Hagopian G, et al. Predictors of prison-based treatment outcomes: a comparison of men and women participants. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2006; 32(1): 7–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission. Lancet 2018; 391: 2642–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Charron E, Mayo RM, Heavner-Sullivan SF, et al. “It’s a very nuanced discussion with every woman”: health care providers’ communication practices during contraceptive counseling for patients with substance use disorders. Contraception 2020; 102(5): 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heil SH, Jones HE, Arria A, et al. Unintended pregnancy in opioid-abusing women. J Subst Abuse Treat 2011; 40(2): 199–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jones HE, Berkman ND, Kline TL, et al. Initial feasibility of a woman-focused intervention for pregnant African-American women. Int J Pediatr 2011; 2011: 389285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McNeely CA, Hutson S, Sturdivant TL, et al. Expanding contraceptive access for women with substance use disorders: partnerships between Public Health Departments and County Jails. J Public Health Manag Pract 2019; 25: 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Armstrong KA, Kennedy MG, Kline A, et al. Reproductive health needs: comparing women at high, drug-related risk of HIV with a national sample. J Am Med Womens Assoc 1999; 54(2): 65–70, 78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Terplan M, Hand DJ, Hutchinson M, et al. Contraceptive use and method choice among women with opioid and other substance use disorders: a systematic review. Prev Med 2015; 80: 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cavanaugh CE, Floyd LJ, Penniman TV, et al. Examining racial/ethnic disparities in sexually transmitted diseases among recent heroin-using and cocaine-using women. J Womens Health 2011; 20(2): 197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brookmeyer KA, Haderxhanaj LT, Hogben M, et al. Sexual risk behaviors and STDs among persons who inject drugs: a national study. Prev Med 2019; 126: 105779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kouyoumdjian FG, Leto D, John S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis in incarcerated persons. Int J STD AIDS 2012; 23(4): 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Binswanger IA, Mueller S, Clark CB, et al. Risk factors for cervical cancer in criminal justice settings. J Womens Health 2011; 20(12): 1839–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kelly PJ, Allison M, Ramaswamy M. Cervical cancer screening among incarcerated women. PLoS ONE 2018; 13(6): e0199220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Soccio J, Brown M, Comino E, et al. Pap smear screening, pap smear abnormalities and psychosocial risk factors among women in a residential alcohol and drug rehabilitation facility. J Adv Nurs 2015; 71(12): 2858–2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hoff E, Adams ZM, Grimshaw A, et al. Reproductive life goals: a systematic review of pregnancy planning intentions, needs, and interventions among women involved in US criminal justice systems. J Womens Health 2020; 30: 412–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Price C, Qin Y, Tracey D, et al. Oral presentation Abstract # 5053: A novel PrEP demonstration project for justice-involved women and members of their risk networks. In: Academic Correctional health conference, Virtual, April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42(2): 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95: 103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meyer J, Price C, Tracey D, et al. Development and efficacy of a PrEP decision aid for women in drug treatment. Patient Prefer Adher 2021; 15: 1913–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Adams ZM, Ginapp CM, Price CR, et al. “A good mother”: impact of motherhood identity on women’s substance use and engagement in treatment across the lifespan. J Subst Abuse Treat 2021; 130: 108474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995; 36(1): 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res 2000; 34(6): 1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen NE, Meyer JP, Avery AK, et al. Adherence to HIV treatment and care among previously homeless jail detainees. AIDS Behav 2013; 17(8): 2654–2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55: 1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018; 320: 674–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, et al. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007; 31(7): 1208–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McLellan AT, Cacciola JC, Alterman AI, et al. The Addiction Severity Index at 25: origins, contributions and transitions. Am J Addict 2006; 15(2): 113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1980; 168(1): 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rikoon SH, Cacciola JS, Carise D, et al. Predicting DSM-IV dependence diagnoses from Addiction Severity Index composite scores. J Subst Abuse Treat 2006; 31(1): 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Calsyn DA, Saxon AJ, Bush KR, et al. The Addiction Severity Index medical and psychiatric composite scores measure similar domains as the SF-36 in substance-dependent veterans: concurrent and discriminant validity. Drug Alcohol Depend 2004; 76: 165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Haukoos JS, Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, et al. Derivation and validation of the Denver Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) risk score for targeted HIV screening. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 175: 838–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States – 2017 update, a clinical practice guideline. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dasgupta A, Davis A, Gilbert L, et al. Reproductive health concerns among substance-using women in community corrections in New York City: understanding the role of environmental influences. J Urban Health 2018; 95(4): 594–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tavoli Z, Mohammadi M, Tavoli A, et al. Quality of life and psychological distress in women with recurrent miscarriage: a comparative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018; 16: 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Thyer BA. Project prevention: concept, operation, results and controversies about paying drug abusers to obtain long-term birth control. William Mary Bill Rights J 2015; 24: 643. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lennard N. The long, disgraceful history of American attacks on Brown and Black women’s reproductive systems. The Intercept, 17 September 2020, https://theintercept.com/2020/09/17/forced-sterilization-ice-us-history/

- 62. National Women’s Health Network. Taking a principled approach to the provision of LARCs, 2016, https://nwhn.org/taking-principled-approach-provision-larcs/

- 63. Daniels K, Abma JC. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–49: United States, 2017–2019. NCHS Data Brief, October 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db388-H.pdf [PubMed]

- 64. Clarke JG, Hebert MR, Rosengard C, et al. Reproductive health care and family planning needs among incarcerated women. Am J Public Health 2006; 96(5): 834–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hale GJ, Oswalt KL, Cropsey KL, et al. The contraceptive needs of incarcerated women. J Womens Health 2009; 18: 1221–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ramaswamy M, Chen HF, Cropsey KL, et al. Highly effective birth control use before and after women’s incarceration. J Womens Health 2015; 24(6): 530–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kelly PJ, Ramaswamy M. The association between unintended pregnancy and violence among incarcerated men and women. J Community Health Nurs 2012; 29(4): 202–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ramaswamy M, Upadhyayula S, Chan KY, et al. Health priorities among women recently released from jail. Am J Health Behav 2015; 39(2): 222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sufrin CB, Creinin MD, Chang JC. Contraception services for incarcerated women: a national survey of correctional health providers. Contraception 2009; 80(6): 561–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ahmadi R, Ziaei S, Parsay S. Association between nutritional status with spontaneous abortion. Int J Fertil Steril 2017; 10(4): 337–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Coleman PK, Reardon DC, Cougle JR. Substance use among pregnant women in the context of previous reproductive loss and desire for current pregnancy. Br J Health Psychol 2005; 10(Pt 2): 255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nijhawan AE, Salloway R, Nunn AS, et al. Preventive healthcare for underserved women: results of a prison survey. J Womens Health 2010; 19(1): 17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Contraception. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and HUman Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 74. El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, et al. Intimate partner violence and HIV among drug—involved women: contexts linking these two epidemics—challenges and implications for prevention and treatment. Subst Use Misuse 2011; 46(2–3): 295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Li Y, Marshall CM, Rees HC, et al. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc 2014; 17: 18845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sundaram A, Vaughan B, Kost K, et al. Contraceptive failure in the United States: estimates from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2017; 49(1): 7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011; 83: 397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455065211070543 for Overlapping needs for sexual and reproductive health and HIV prevention in women with substance use disorders by Britton Gibson, Emily Hoff, Alissa Haas, Zoe M Adams, Carolina R Price, Dawn Goddard-Eckrich, Sangini S Sheth, Anindita Dasgupta and Jaimie P Meyer in Women’s Health