Abstract

Introduction

KRAS mutations are identified in ~30% of patients with NSCLC. Novel direct inhibitors of KRAS G12C have shown activity in early phase clinical trials. We hypothesized that patients with KRAS G12C mutations may have distinct clinical characteristics and responses to therapies.

Methods

Through routine next-generation sequencing, we identified patients with KRAS-mutant NSCLC treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center from 2014–2018 and reviewed tumor characteristics, overall survival, and treatment outcomes.

Results

We identified 1194 patients with KRAS-mutant NSCLC, including 770 with recurrent or metastatic disease. KRAS G12C mutations were present in 46% and KRAS non-G12C mutations in 54%. Patients with KRAS G12C had a higher tumor mutation burden (median 8.8 mut/Mb vs 7.0 mut/Mb, p=0.006) and higher median PD-L1 expression (5% vs 1%). The co-mutation patterns of STK11 (28% vs 29%) and KEAP1 (23% vs 24%) were similar. The median overall survivals from diagnosis were similar for KRAS G12C (13.4 months) and KRAS non-G12C mutations (13.1 months, p=0.96). In patients with PD-L1 ≥50%, there was not a significant difference in response rate with single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitor for patients with KRAS G12C mutations (40% vs 58%, p=0.07).

Conclusions:

We provide outcome data for a large series of patients with KRAS G12C-mutant NSCLC with available therapies, demonstrating that responses and duration of benefit with available therapies are similar to those seen in patients with KRAS non-G12C mutations. Strategies to incorporate new targeted therapies into the current treatment paradigm will need to consider outcomes specific to patients harboring KRAS G12C mutations.

Introduction

Over the past decade, there have been improvements in survival for patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), due to many factors including improved staging and more effective therapies for patients with lung cancer1. While chemotherapy remains a mainstay of therapy, the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors has become standard given survival benefits observed with these agents2,3. Molecularly targeted therapies have also improved outcomes for patients with specific actionable molecular drivers (EGFR, ALK, ROS1, MET Exon 14, BRAF V600E, RET, and NTRK). Such indications for targeted therapies have led to widespread tumor genomic profiling for patients with NSCLC which is now considered standard of care for all patients diagnosed with metastatic disease.

Mutations in KRAS are one of the most commonly identified driver oncogenes, occurring in 25–30% of patients with lung adenocarcinoma4. KRAS G12C is the most common mutation subtype, present in approximately 40% of patients with KRAS mutant lung cancer5. The mutant KRAS protein has long been considered “undruggable”, and efforts to target downstream signaling pathways have been largely ineffective6,7. However, direct KRAS G12C inhibitors are now in clinical development8 and these agents have the potential to change this treatment paradigm. How these therapies will compare to other routinely used systemic therapies (chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors) is not yet known and, to date, there have been no randomized trials comparing KRAS G12C inhibitors to other available therapies in patients with KRAS G12C mutations. We hypothesized that with currently available therapies, the outcomes for patients with KRAS G12C mutant NSCLC would be different compared to patients with KRAS non-G12C subtypes and set out to describe baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes with available therapies for these patients.

Methods

A medical record search was used to identify individuals seen at Memorial Sloan Kettering with a primary tumor diagnosis of lung cancer who had also undergone tissue based hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) testing with MSK-IMPACT9 from January of 2014 to December 2018. Analysis was performed using IMPACT assay version 1 (341 genes) for 71 samples, version 2 (410 genes) for 294 samples, and version 3 (468 genes) for 405 samples. Normalized mutation burden was calculated as the absolute mutation burden (number of nonsynonymous mutations/sample) divided by the genomic coverage for that sample (0.98 Mb for version 1, 1.06 Mb for version 2, and 1.22 Mb for version 3).

Medical records were reviewed to identify those patients with metastatic disease at time of diagnosis or recurrence during follow up period. Data collection was approved by the MSKCC Institutional Review Board/Privacy Board, in accordance with U.S. Common Rule guidelines. Clinical characteristics and first- and second-line treatments were collected for all patients. Baseline characteristics were compared with the Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test for categorical data and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous data. Overall survival was calculated from time of diagnosis of metastatic/recurrent disease to date of death or last follow up, with left truncation to account for time of MSK-IMPACT. Overall survival was compared between groups using the Cox proportional-hazards model.

Benefit from chemotherapy was assessed by time to treatment discontinuation (TTD) analysis and similarly compared between groups using the Cox proportional-hazards model including left truncation analysis incorporating date of molecular testing. For treatment specific outcomes in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor, assessments of best overall response (BOR) and progression were performed by independent thoracic radiologists in accordance with RECIST 1.1. Response rates were compared between groups with Fisher’s exact test. Progression-free survival was calculated from time of treatment start to date of progression, death or last follow up, also including left truncation for date of molecular testing and using the Cox proportional-hazards model for analysis.

Results

Clinical, molecular, and pathologic characteristics

We identified 1194 patients with non-small cell lung cancer who underwent NGS testing from January 2014 to December 2018 whose tumors harbored a KRAS mutation. Disease course was reviewed, and 770 patients were identified who had metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis or developed recurrent disease during follow up. The median duration of follow up for these patients was 13.8 months. The clinical characteristics of patients with advanced/metastatic lung cancer harboring KRAS mutations are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age or sex when patients with KRAS G12C mutations were compared to those with non-G12C mutations. There was a lower proportion of patients who had never smoked among patients with KRAS G12C mutations (1% vs 10%, p<0.001) compared to KRAS non-G12C subtypes.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics and treatment history of patients with metastatic KRAS mutant non-small cell lung cancer according to KRAS mutation subtype

| Overall (N=772) | Non-G12C subtype (n=418) | G12C subtype (n=352) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis – median (range) | 69 (27, 93) | 68 (27, 89) | 69 (38, 93) | 0.24 |

| Female gender | 476 (62%) | 252 (60%) | 222 (63%) | 0.46 |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | |||

| Current | 164 (21%) | 91 (22%) | 73 (21%) | |

| Former | 561 (73%) | 287 (68%) | 274 (78%) | |

| Never | 47 (6%) | 40 (10%) | 5 (1%) | |

| Metastatic disease at diagnosis | 520 (67%) | 290 (69%) | 228 (65%) | |

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 666 (86%) | 377 (90%) | 288 (82%) | |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 12 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma | 8 (1%) | 2 (<1%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Adenosquamous Carcinoma | 7 (1%) | 2 (<1%) | 5 (1%) | |

| NSCLC NOS | 79 (10%) | 32 (8%) | 47 (13%) | |

| Tumor mutation burden – median (range) | 7.9 (0.9, 55.1) | 7.0 (0.9, 55.1) | 8.8 (0.9, 37.7) | 0.006 |

| PD-L1 expression – median (range), N | 1.5 (0, 100), 492 | 1 (0, 100), 269 | 5 (0, 100), 223 | 0.04 |

| 0% | 222 (45%) | 129 (48%) | 93 (42%) | |

| 1–49% | 116 (24%) | 67 (25%) | 49 (22%) | |

| 50–100% | 154 (31%) | 73 (27%) | 81 (36%) | |

| Treatment Received | ||||

| Platinum Doublet Chemotherapy (1L or 2L) | 379 (49%) | 212 (50%) | 167 (47%) | |

| Immune checkpoint Inhibitor (1L or 2L) Single agent PD-(L)1 Inhibitor PD-(L)1 + CTLA-4 Inhibitor |

337 (46%) 308 (39%) 29 (4%) |

194 (46%) 175 (42%) 19 (5%) |

143 (40%) 133 (38%) 10 (3%) |

0.43 |

| Chemotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 antibody (1L) | 55 (7%) | 33 (8%) | 22 (6%) |

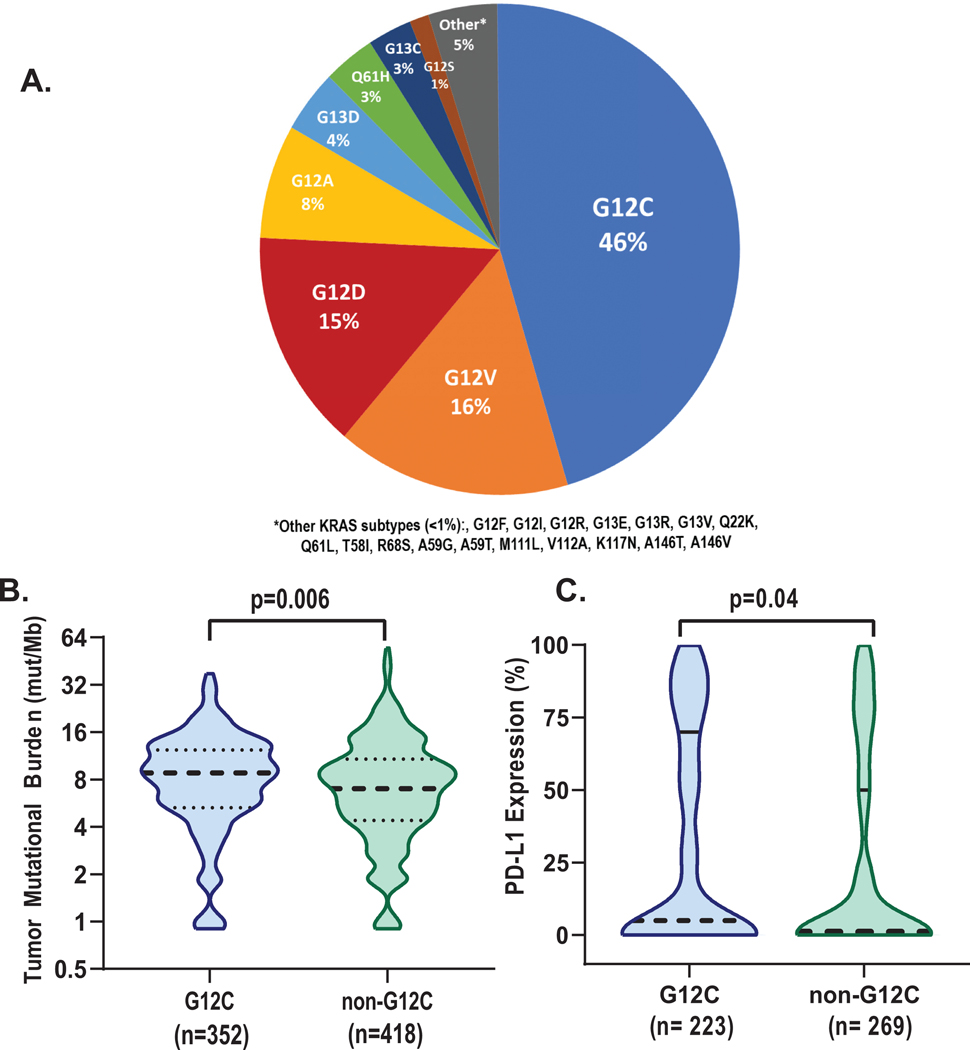

The most common KRAS mutation subtype identified was KRAS G12C (n=352, 46%, Figure 1A). Other subtypes identified included G12V (n=121, 16%), G12D (n=112, 15%), and G12A (n=58, 8%). TP53, STK11, and KEAP1 were the three most commonly co-occurring mutations in tumors. The frequency of TP53 mutations was similar in KRAS G12C vs KRAS non-G12C tumors (43 vs 41%, p=0.6), as was the case with STK11 mutations (28 vs 29%, p=1.0) and KEAP1 alterations (23 vs 24%, p=0.9). The median tumor mutational burden was higher in tumors harboring KRAS G12C compared to non-G12C subtypes (median 8.8 mut/Mb vs 7.0 mut/Mb, p=006, Figure 1B).

Figure 1:

KRAS Mutation subtypes and baseline pathologic and molecular characteristics. A. In cohort of 772 patients with metastatic NSCLC, KRAS G12C was the most common mutation. G12V, and G12D, and G12A were the most common non-G12c subtypes observed. B. Median tumor mutational burden was higher in samples with G12C alterations (8.8 vs 7.0, p=0.006), C. Higher median PD-L1 expression was observed in G12C samples (5% vs 1%, p=0.04).

Information about PD-L1 expression was available for 492/770 (64%) tumor samples. Median PD-L1 expression was higher in patients with KRAS G12C mutations than KRAS non-G12C subtypes (5% vs 1%, p=0.04, Figure 1C, Table 1). Accordingly, in tumors with KRAS G12C mutations, high PD-L1 expression (≥50%) was more common, identified in 36% (81/223) of cases compared to 27% (73/269) in non-G12C subtypes (p=0.03). Intermediate PD-L1 expression (1–49%) was identified in 22% (49/223) of G12C cases compared to 25% (67/269) of non-G12C cases. Within samples with high PD-L1 expression (≥50%), frequency of STK11 and KEAP1 co-mutations was overall low, though similar between both KRAS G12C and non-G12C subtypes (STK11:11% vs 8%; KEAP 11%, vs 12%, respectively). The frequency of TP53 mutations was higher and more consistent with the entire cohort irrespective of PD-L1 expression (62% vs 64% in G12C vs non-G12C samples).

Impact of KRAS G12C on treatment outcomes

Treatment records were reviewed for all patients with advanced/metastatic disease with a specific focus on first- and second-line therapies administered (Table 1). As first line therapy, 45% (351/772) of patients were treated with platinum-doublet chemotherapy, 19% (147/772) of patients were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor, and a small number of patients were treated with chemo-immunotherapy combinations (7%, 55/772). Formal response assessments were available for 284/337 patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors and this cohort was used for further analysis of treatment specific outcomes.

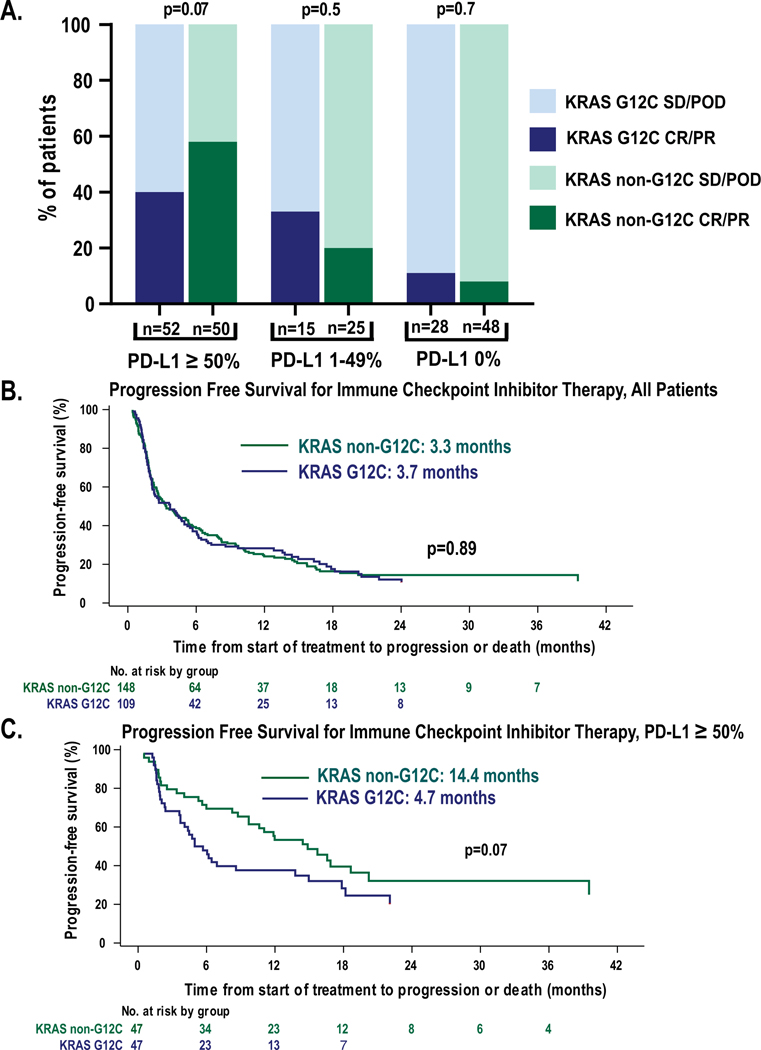

The overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibitor was similar in G12C and non-G12C patients (26% vs 28%, respectively, p=0.7). We next assessed the response rate in patients with available PD-L1 expression (Figure 2A). In patients with high PD-L1 expression (≥50%), the response rate was similar in those patients with non-G12C mutation subtypes (n=50) compared to G12C (n=52) (58% vs 40% p=0.07). Response rates in those patients with intermediate PD-L1 expression (1–49%) were similar in both groups (20 vs 33%, p=0.4) and similar findings were noted in those patients with absent PD-L1 expression (8% vs 11%, p=0.7).

Figure 2:

Response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with KRAS G12C mutation subtype compared to non-G12C subtypes. A. Best overall response to immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment, depicted in three PD-L1 subgroups reflecting high, intermediate, and absent PD-L1 expression. B. In unselected patient population, median progression free survival for patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor was similar (3.3 vs 3.7 months, p=0.8). C. In patients with high expression of PD-L1 (≥50%), patients with G12C mutations had shorter duration of response (14.4 vs 4.7 moths, p=0.07).

In patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, the median progression free survival was 3.7 months in patients with G12C mutations compared to 3.3 months in those with non-G12C mutations (p=0.89, Figure 2B). In those patients with PD-L1 expression ≥50%, the median progression free survival in patients with G12C subtypes was 4.7 months compared to 14.4 months in patients with non-G12C subtypes (p=0.07, Figure 2C). Of those patients with high (≥ 50%) PD-L1 expression, 77/102 were treated in the first line setting for metastatic disease and within these patients PFS was similar to the larger sample was (5 vs 17 months, p=.07).

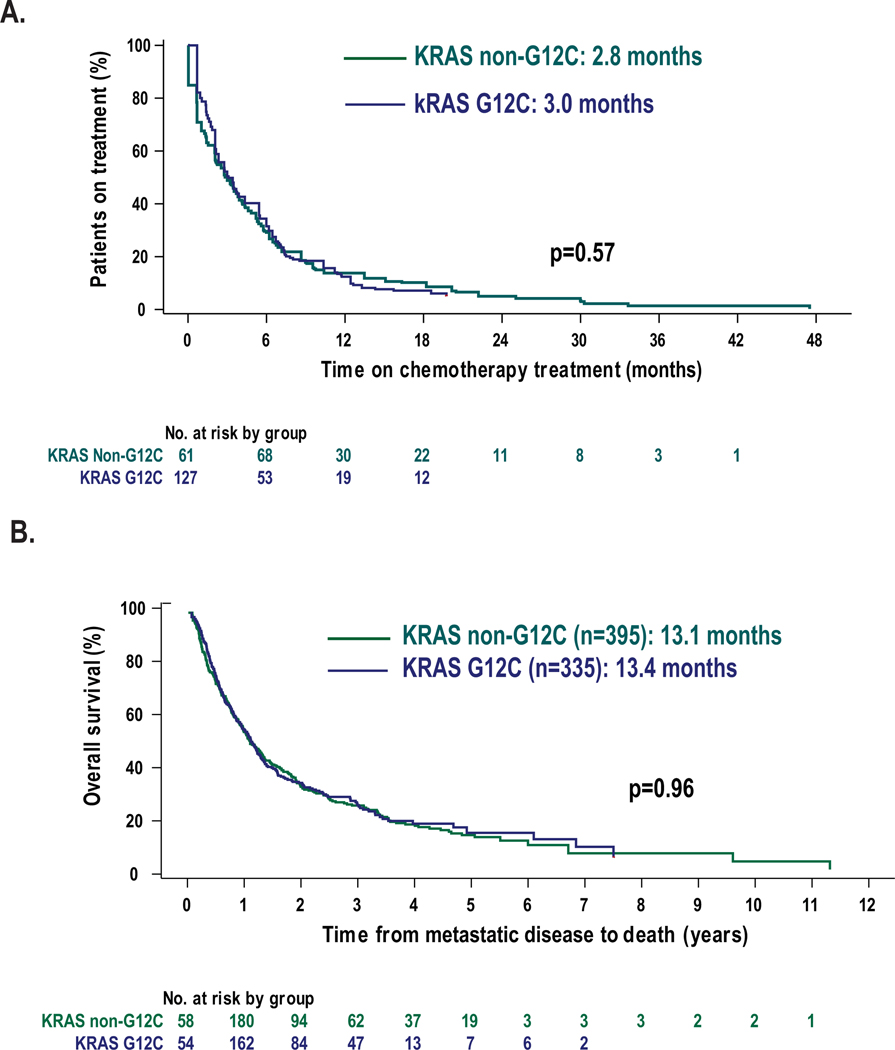

Given the evolving standard of care in the first line setting during this period of time, patients who received first- or second-line treatment with platinum-doublet chemotherapy were grouped together. There were 167 patients with KRAS G12C mutations (47%) and 212 patients with non-G12C subtypes (50%) who underwent treatment with platinum-doublet chemotherapy. Pemetrexed and platinum combinations were the most common treatment regimens administered. The median time to treatment discontinuation was similar in both G12C and non-G12C patients (3.0 vs 2.8 months, p=0.57, Figure 3A). Among 55 patients treated with chemotherapy-immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations in the first line setting, the median time to treatment discontinuation for patients with KRAS G12C was 9.3 months compared to 3.8 months for those patients with KRAS non-G12C subtypes (HR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.40–1.43, p=0.4).

Figure 3:

Outcomes to treatment with chemotherapy and comparison of overall survival in patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC. A. In patients treated with platinum-doublet chemotherapy as first- or second-line therapy, time to treatment discontinuation for both KRAS G12C and non-G12C subtypes were similar (3.0 vs 2.8 months, p=0.57). B. Overall survival from time of metastatic diagnosis is similar in G12C and non-G12C subtypes (13.4 vs 13.1 months, p=0.99).

Overall survival

To assess prognosis, we evaluated survival from the time of diagnosis of metastatic disease for patients with advanced/metastatic disease. To account for left truncation, patients entered the risk set at the date of molecular NGS testing rather than date of metastatic/recurrent disease diagnosis. In 40/770 cases, the patient died prior to results of NGS tissue testing, and therefore these patients were not included in the overall survival analysis. The median overall survival for patients with KRAS G12C mutation subtypes was the same as those with KRAS non-G12C subtypes 13.4 vs 13.1 months, p=0.96, Figure 3B).

Discussion

Patients with lung cancer harboring KRAS G12C mutations are poised to enter a new era of treatment modalities as new direct inhibitors are in clinical development. Here we highlight the clinical differences of these patients, notably that these KRAS G12C mutations are predominantly found in patients with smoking history consistent with other prior reports10. We provide outcome data for a large cohort of patients with KRAS G12C mutations and their response to available therapies, demonstrating similar outcomes for patients with KRAS G12C and KRAS non-G12C.

While some prior reports have suggested that there may be differences in treatment outcomes for patients with different KRAS mutation subtypes, other series, including those incorporating multivariable analyses, did not show a difference in survival11,12. In this report, in patients receiving more modern therapies including routine use of immune checkpoint inhibitors, we did not observe a difference in overall survival when comparing patients with KRAS G12C mutations to other KRAS mutation subtypes. Importantly, we observed that the prevalence of STK11 and KEAP1 co-mutations, previously reported to be associated with poorer overall survival and more aggressive disease course5,13, were similar in patients with KRAS G12C mutations and KRAS non-G12C mutations

KRAS G12C inhibitors in development are the first direct inhibitors of this mutant protein to demonstrate efficacy in clinical trials. The KRAS protein normally cycles between active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bound confirmations through intrinsic GTPase activity which is enhanced by GTPase-activating proteins. Activating KRAS mutations (such as KRAS G12C), impair GAP-stimulated hydrolysis and lead to a predominantly GTP-bound (i.e. active) oncoprotein. Identification of a binding pocket of KRAS G12C14 was an important breakthrough and enabled the development of covalent inhibitors, which selectively bind to the mutant cysteine and spare wild type or other mutant KRAS proteins. These drugs bind only to GDP-bound (i.e. inactive) KRAS G12C and trap the oncoprotein in its inactive state by preventing nucleotide exchange15. Two agents (sotarasib8 and MRTX84916) have demonstrated efficacy in early phase clinical trials. While these drugs are a substantial improvement compared to other targeted therapy approaches for KRAS mutant NSCLC6,7, the overall response rate observed in NSCLC patients treated with sotorasib was only 32% with median progression free survival of 6.2 months. Therefore, use of these compounds in clinical practice will need to be carefully considered in the context of other therapeutic options (e.g. platinum-doublet chemotherapy, combination chemo-immunotherapy, and immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy).

Currently, patients with KRAS G12C mutations are grouped with all other patients who are considered to lack a targetable oncogenic driver. For such patients, first-line therapy decisions are made considering PD-L1 expression on tumor tissue. For those patients with PD-L1 expression ≥50%, single-agent therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitor is a standard of care given survival benefits demonstrated in randomized clinical trials compared to platinum-doublet chemotherapy.2,17 Like other prior reports18, we did not find a difference in outcomes to immune checkpoint inhibitor with respect to mutation subtype when patients were considered irrespective of PD-L1 expression status. A subset analysis of a prospective clinical trial demonstrated benefit of pembrolizumab compared to chemotherapy in patients with KRAS G12C mutant NSCLC with PD-L1 expression ≥1%.19

Here we show that among patients with high PD-L1 expression, those with KRAS G12C mutations may have less durable response to immune checkpoint inhibitors than even other KRAS non-G12C subtypes. The median progression free survival for patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors was similar in patients with both G12C and non-G12C subtypes. However, in this cohort of patients who received first-line therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors, progression free survival of at least 12 months occurred in 59% (22/37) of patients with non-G12C subtypes but only 29% (11/38) of patients with G12C mutations. At this time, pembrolizumab remains standard of care first-line therapy for patients with KRAS G12C mutant NSCLC, however this may evolve as further efficacy data becomes available from KRAS G12C inhibitors in clinical development. The interplay between the immune system and specific molecular alterations has been an area of considerable interest. The efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors is lower in patients with EGFR or ALK alterations. We and others have suggested that the presence or absences of specific co-mutations (e.g. STK1120 and KEAP19) may also affect the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, specifically in patients with KRAS mutant lung cancer. While concurrent STK11 mutation has been implicated in poor outcomes in immune checkpoint inhibitors in KRAS mutant NSCLC20, the rate of concurrent STK11 mutation was low in both G12C (4/52, 8%) and non-G12C subtypes (4/50, 8%) in the group with high PD-L1 expression, consistent with other reports21 and therefore unlikely to explain this difference. Why tumors driven by KRAS G12C may be less responsive to this class of therapy compared to other subtypes has not been well described and our findings will need to be confirmed in larger series. Interestingly, in KRAS G12C mutant mouse models, treatment with a direct G12C inhibitor led to infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the tumor as well as macrophages and dendritic cells potentially due to an increased intratumoral concentration of chemokines.22

While any single, retrospective analysis has inherent limitations, this patient cohort reflects modern treatment practices including the routine use of immune checkpoint inhibitors that are now a mainstay of therapy for patients with lung cancer and is considerably larger than the KRAS cohorts from available prospective clinical trials19,23.The rapidly evolving standard of care for treatment of metastatic NSCLC is evident in this cohort as most, but not all patients received now-standard therapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors. Furthermore, treatment-specific outcomes to immune checkpoint inhibitors can be difficult to quantify given that patients may discontinue therapy for reasons other than progression and continue to maintain response. The responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors reported here were performed by independent thoracic radiologists according to RECIST 1.1 criteria. Analysis was limited to those patients with formal response assessments available, and although this constituted the majority of patients, may introduce an unintended bias. Outcomes for those patients treated with chemotherapy are limited to time to treatment discontinuation as opposed to formal response assessments such as ORR and PFS though assessments linked to treatment duration likely to be reasonable proxies for outcomes given the nature of standard lung cancer chemotherapy regimens24. We are also largely unable to comment on the efficacy of chemo-immunotherapy regimens in this population given that adequate sample size and follow up was not yet available to make definitive conclusions. Given that these chemo-immunotherapy regimens are standard for most patients (those with PD-L1 expression <50%), it will be imperative in future cohorts to assess outcomes to these regimens once adequate follow up is available. Finally, another potential limitation of the analysis is that the group of non-G12C KRAS-mutated NSCLC is heterogeneous with respect to smoking history (including that group of patients with KRAS G12D mutations who were more likely to be never smokers). 10 Clinical variables such as smoking history may also confound other genomic features such as TMB and impact differences observed. Furthermore, other clinical variables that have been associated with response to therapy and prognosis (e.g. brain metastases25, tumor burden, serum inflammatory markers26) are not included in this analysis but potentially warrant further investigation in the future.

Direct KRAS G12C inhibitors represent a potentially important advance for the treatment of metastatic lung cancer and larger reports of efficacy of these agents is eagerly awaited. The true benefit of these therapies will need to be judged compared to other available therapies, the activity of which may be different for patients with KRAS G12C mutations compared to other KRAS mutation subtypes and consider other features such as PD-L1 expression. A nuanced assessment will enable incorporation of targeted therapy in a way that will hopefully meaningfully improve survival for patients with KRAS G12C mutations.

Statement of translational relevance:

Patients with KRAS mutant NSCLC can have a heterogeneous clinical course and their response to current therapies such as chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors is variable. KRAS G12C is the most common KRAS mutation and recent discoveries have enabled the development of direct inhibitors that have entered the clinic. Improvements in outcomes for these patients will require consideration of therapy in the context of available therapies. We describe the clinical and molecular characteristics of patients with KRAS G12C mutant NSCLC compared to other KRAS molecular subtypes including the presence of frequently co-occurring mutations. Evaluation of treatment specific outcomes suggest that responses to chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors are similar in patients with KRAS G12C mutant NSCLC compared to other mutation subtypes although there remains a significant need to further characterize this molecular subtype of NSCLC given the rapidly evolving treatment landscape.

Acknowledgements:

This study was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through the NCI of the NIH (P30 CA008748). K.C.A. is supported in part by the LUNGevity Foundation. M.D.H. is supported in part by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation Clinical Investigator Award grant no. CI-98-18 and is a member of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. P.L. PL is supported in part by the NIH/NCI (1R01CA230745-01 and 1R01CA230267-01A1), the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation.

Conflict of Interest Statement

K.C.A has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca and Iovance Biotherapeutics. Her institution has received research support on her behalf from Takeda and Novartis. M.D.H. receives research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb; has been a compensated consultant for Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Nektar, Syndax, Mirati, Shattuck Labs, Immunai, Blueprint Medicines, Achilles, and Arcus; received travel support/honoraria from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; has options from Shattuck Labs, Immunai, and Arcus; has a patent filed by his institution related to the use of tumor mutation burden to predict response to immunotherapy (PCT/US2015/062208), which has received licensing fees from PGDx.H.A.Y. has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Daiichi, Blueprint Med, Janssen, C4 Therapeutic. She has also received research funding to my institution from AstraZeneca, Daiichi, Cullinan, Novartis, Lilly, and Pfizer. M.L. has received advisory board compensation from Merck, Lilly Oncology, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, Blueprint Medicines, and Bayer, and research support from LOXO Oncology, Helsinn Healthcare, Elevation Oncology and Merus M.G.K has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Daiichi-Sankyo. M.E.A. has served as a consultant and received honoraria from Invivoscribe and Biocartis. C.M.R has consulted regarding oncology drug development with AbbVie, Amgen, Ascentage, Astra Zeneca, Bicycle, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Genentech/Roche, Ipsen, Jazz, Lilly, Pfizer, PharmaMar, Syros, and Vavotek. He serves on the scientific advisory boards of Bridge Medicines, Earli, and Harpoon Therapeutics. P.L. is an inventor on two patents filed by MSK and has received research grants to his institution from Amgen, Mirati Therapeutics and Revolution Medicines. G.J.R reports institutional research funding from Mirati, Pfizer, Novartis, Merck, and Roche.

References

- 1.Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, et al. The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):640–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1–Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jordan EJ, Kim HR, Arcila ME, et al. Prospective Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Lung Adenocarcinomas for Efficient Patient Matching to Approved and Emerging Therapies. Cancer Discov. Published online January 1, 2017:CD-16–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arbour KC, Jordan E, Kim HR, et al. Effects of Co-occurring Genomic Alterations on Outcomes in Patients with KRAS-Mutant Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(2):334–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jänne PA, Heuvel MM van den, Barlesi F, et al. Selumetinib Plus Docetaxel Compared With Docetaxel Alone and Progression-Free Survival in Patients With KRAS-Mutant Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: The SELECT-1 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317(18):1844–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumenschein GR, Smit EF, Planchard D, et al. A randomized phase II study of the MEK1/MEK2 inhibitor trametinib (GSK1120212) compared with docetaxel in KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol. 2015;26(5):894–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.KRASG12C Inhibition with Sotorasib in Advanced Solid Tumors | NEJM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17(3):251–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dogan S, Shen R, Ang DC, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS Mutations in 3,026 Lung Adenocarcinomas: Higher Susceptibility of Women to Smoking-Related KRAS-Mutant Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(22):6169–6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu HA, Sima CS, Shen R, et al. Prognostic Impact of KRAS Mutation Subtypes in 677 Patients with Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinomas. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(3):431–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruppert A-M, Beau-Faller M, Debieuvre D, et al. Outcomes of Patients With Advanced NSCLC From the Intergroupe Francophone de Cancérologie Thoracique Biomarkers France Study by KRAS Mutation Subtypes. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2020;1(3):100052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen R, Martin A, Ni A, et al. Harnessing Clinical Sequencing Data for Survival Stratification of Patients With Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinomas. JCO Precis Oncol. Published online March 28, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML, Wells JA, Shokat KM. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature. 2013;503:548–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lito P, Solomon M, Li L-S, Hansen R, Rosen N. Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. Science. 2016;351(6273):604–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallin J, Engstrom LD, Hargis L, et al. The KRASG12C Inhibitor MRTX849 Provides Insight toward Therapeutic Susceptibility of KRAS-Mutant Cancers in Mouse Models and Patients. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(1):54–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mok TSK, Wu Y-L, Kudaba I, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1819–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeanson A, Tomasini P, Souquet-Bressand M, et al. Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in KRAS-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(6):1095–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbst RS, Lopes G, Kowalski DM, et al. LBA4 Association of KRAS mutational status with response to pembrolizumab monotherapy given as first-line therapy for PD-L1-positive advanced non-squamous NSCLC in Keynote-042. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:xi63–xi64. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skoulidis F, Goldberg ME, Greenawalt DM, et al. STK11/LKB1 Mutations and PD-1 Inhibitor Resistance in KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(7):822–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoenfeld AJ, Rizvi H, Bandlamudi C, et al. Clinical and molecular correlates of PD-L1 expression in patients with lung adenocarcinomas✰. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(5):599–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY, et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2019;575(7781):217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gadgeel S, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Felip E, et al. LBA5 - KRAS mutational status and efficacy in KEYNOTE-189: Pembrolizumab (pembro) plus chemotherapy (chemo) vs placebo plus chemo as first-line therapy for metastatic non-squamous NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:xi64–xi65. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumenthal GM, Gong Y, Kehl K, et al. Analysis of time-to-treatment discontinuation of targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy in clinical trials of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Offin M, Feldman D, Ni A, et al. Frequency and outcomes of brain metastases in patients with HER2-mutant lung cancers. Cancer. 2019;125(24):4380–4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mezquita L, Auclin E, Ferrara R, et al. Association of the Lung Immune Prognostic Index With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Outcomes in Patients With Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]