Abstract

In RNA interference (RNAi), small interfering RNA (siRNA) functions to suppress the expression of its target mRNA with perfect sequence complementarity. In a mechanism different from above, siRNA also suppresses unintended mRNAs with partial sequence complementarities, mainly to the siRNA seed region (nucleotides 2–8). This mechanism is largely utilized by microRNAs (miRNAs) and results in siRNA-mediated off-target effects. Thus, the siRNA seed region is considered to be involved in both RNAi and off-target effects. In this study, we revealed that the impact of 2′-O-methyl (2′-OMe) modification is different according to the nucleotide positions. The 2′-OMe modifications of nucleotides 2–5 inhibited off-target effects without affecting on-target RNAi activities. In contrast, 2′-OMe modifications of nucleotides 6–8 increased both RNAi and off-target activities. The computational simulation revealed that the structural change induced by 2′-OMe modifications interrupts base pairing between siRNA and target/off-target mRNAs at nucleotides 2–5 but enhances at nucleotides 6–8. Thus, our results suggest that siRNA seed region consists of two functionally different domains in response to 2′-OMe modifications: nucleotides 2–5 are essential for avoiding off-target effects, and nucleotides 6–8 are involved in the enhancement of both RNAi and off-target activities.

1. Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) is a post-transcriptional gene-silencing mechanism triggered by small interfering RNA (siRNA), which is a 21-nucleotide-long double-stranded RNA with two-nucleotide 3′ overhangs.1−5 When the siRNA duplex is introduced into cells, it is loaded onto the Argonaute (AGO) protein, a core protein of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (Figure 1A).6−10 On the AGO protein, the duplex is unwound into two RNA strands, one of which (the guide strand) remains on the AGO protein, whereas the other (the passenger strand) is degraded.11−14 The guide strand recognizes the target mRNA with perfect sequence complementarity, and the target mRNA is cleaved by AGO2, resulting in the suppression of the target gene.8−10 Thus, RNAi is widely recognized as a powerful tool for functional genomics and a promising candidate for therapeutic applications. RNAi and the related RNA silencing mechanisms are observed in a variety of evolutionarily diverse organisms.15 However, effective siRNAs are limited in mammalian cells; the identification of functional siRNA sequence rules is essential for developing effective mammalian RNAi. We previously found that siRNAs that simultaneously satisfy the following four sequence conditions are functional: (i) A/U at the 5′ end of the siRNA guide strand, (ii) G/C at the 5′ end of the passenger strand, (iii) four or more A/U residues in the seven-nucleotide 5′ terminus of the guide strand, and (iv) no G/C stretch ≥9 nucleotides long (Figure 1B).16 The siRNAs that satisfy all of these four rules simultaneously are classified as class I siRNAs. By contrast, siRNAs that satisfy none of these conditions are classified into class III, and those classified into neither class I nor III are named as class II. The importance of these conditions has been verified in a number of studies, and the asymmetry in the stabilities of both siRNA termini is essential for determining the unwinding direction of the siRNA duplex into single-stranded RNAs.17−19 The 5′-terminus unwound from unstable termini is anchored in a binding pocket in the MID-domain of the AGO protein. The binding affinity of A or U at the 5′ terminus in the pocket is 30-fold higher than that of either G or C.20 Thus, an RNA strand with an unstable 5′ terminus acts as a functional guide RNA.

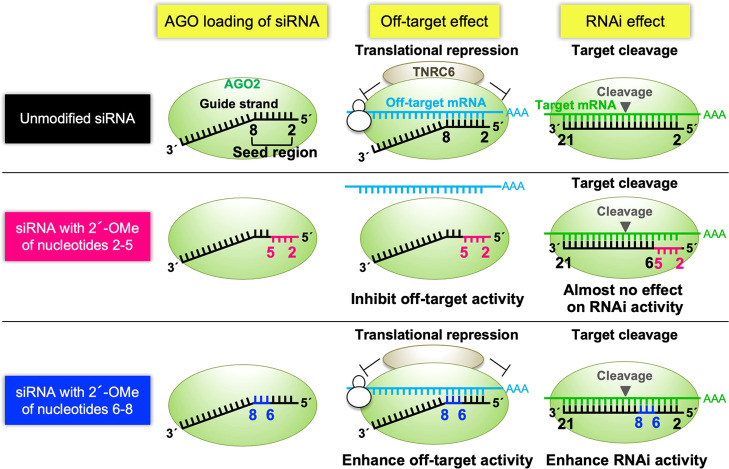

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of siRNA-mediated RNAi and off-target effects. (A) The siRNA is a double-stranded RNA composed of 21-nucleotide-long guide and passenger strands. siRNA transfected into cells is loaded onto the AGO2 protein, and the passenger strand is removed. The guide strand base-pairs with target and off-target mRNAs through sequence complementarity with the seed region. The guide RNA then base-pairs with target mRNA with a perfect complementary sequence and cleaves it with AGO2 to repress its expression. On the other hand, the expression of off-target mRNAs with sequences complementary to the siRNA seed region is reduced by off-target effects, which is a mechanism like miRNA-mediated translational repression. (B) In mammalian cells, a limited fraction of siRNAs is known to be functional. According to the levels of predicted silencing activities, siRNAs are classified into classes I, II, and III. Class I siRNA is a functional siRNA in mammalian cells. Class I siRNA has A/U at the 5′ end of the guide strand, G/C at the 5′ end of the passenger strand, more than 4 A/Us in the seven-nucleotide 5′ terminus of the guide strand, and no GC stretch longer than eight nucleotides. Class III siRNA is a nonfunctional siRNA and has G/C at the 5′ end of the guide strand, A/U at the 5′ end of the passenger strand, and more than 4 G/Cs within the seven-nucleotide region at the 5′ end of the guide strand. Class II siRNAs are those classified into neither class I nor class III.

In a distinct mode of action, siRNA suppresses mRNAs with only partial sequence complementarity through a mechanism similar to that of microRNA (miRNA)-mediated RNA silencing. This phenomenon causes off-target effect by siRNAs. The off-target transcripts have complementary sequences with the siRNA seed region (nucleotides 2–8) in their 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs).21−28 In the human RISC, the backbone phosphates of the siRNA seed nucleotides are ordered on a quasi-helical structure on the surface of the AGO protein to serve as the entry or nucleation site for mRNA in the A-helix form.29,30 This seed-dependent off-target effect is highly correlated with the thermodynamic stability in the duplex formed between the siRNA seed region and its target mRNAs: the higher the seed-target base-pairing stability, the higher the off-target effect.31 Since the thermodynamic stability is nucleotide sequence-dependent, it is necessary to select siRNA with a seed sequence with lower thermodynamic stability to avoid off-target effects. However, this process decreases the number of selectable siRNAs to 2.1% among all of the possible 21 nucleotide sequences in humans.32 It was demonstrated that a few types of modifications in the seed region affect the seed-matched (SM) off-target effects: 2′-O-methyl (OMe) modification of the second position of the siRNA guide strand has been reported to reduce off-target effect without severely reducing RNAi activity and unlocked nucleic acid modification of the seventh position also reduced SM off-target effects.33,34 Furthermore, we have revealed that the introduction of 2′-OMe into nucleotides 2–8 in the siRNA guide strand reduces off-target effects by inducing the steric hindrance of duplex formation between the siRNA guide strand and mRNA on the AGO protein without affecting RNAi activity.35 As for the non-seed region, 2′-OMe modifications at position 14 and 3′ termini were also shown to affect RNAi activities.36,37

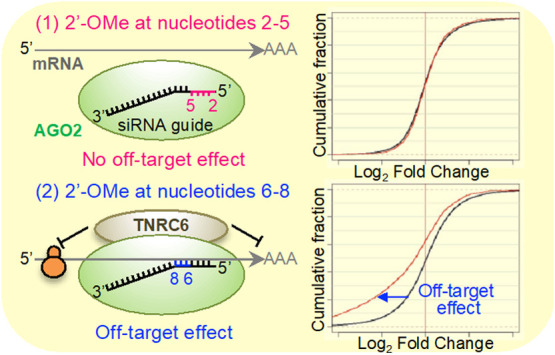

In this study, we performed the more detailed experiments on the position-dependent effect of 2′-OMe modification in the siRNA seed region and found that the siRNA seed region is composed of two functionally different domains in response to 2′-OMe modifications: nucleotides 2–5 and 6–8. The 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 function to reduce off-target activity due to steric hindrance without affecting completely matched (CM) on-target RNAi activity, but those at positions 6–8 enhance both on-target and most of the off-target activities.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Effects of Sequential 2′-OMe Modifications in the Seed Region of the siRNA Guide Strand on RNAi and Off-Target Activities

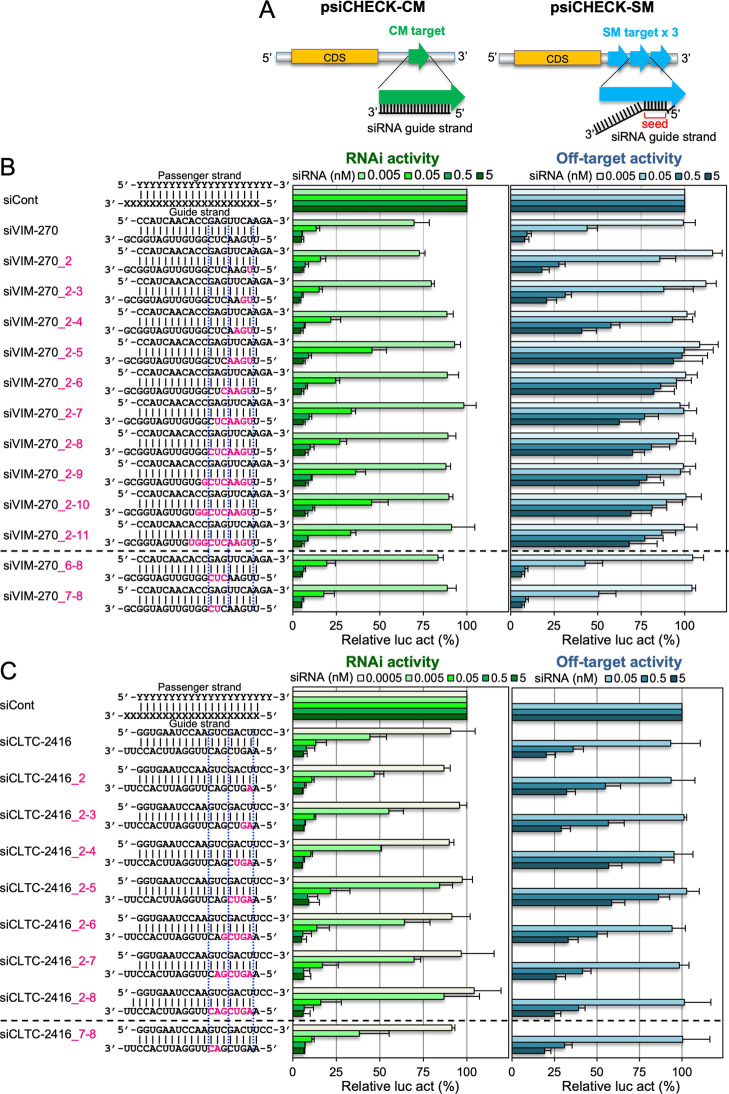

In our previous report, the introduction of 2′-OMe into the siRNA seed region (nucleotides 2–8) reduced off-target activity without affecting RNAi activity.35 To investigate the position-dependent effects of 2′-OMe modifications in the siRNA seed region in more detail, RNAi and seed-dependent off-target activities of the sequential 2′-OMe modifications in the siRNA seed region were investigated using luciferase reporter assays (Figure 2A). The class I siRNAs against human vimentin (siVIM-270) and the clathrin heavy chain (siCLTC-2416) were used for the reporter assays (Figure 2B,C).

Figure 2.

Effects of 2′-OMe modifications of the siRNA guide strand on RNAi and off-target activities. (A) Schematic representation of RNAi (left) and off-target (right) reporter assays. The psiCHECK-1 plasmids containing CM or three tandem repeats of SM sequences of the siRNA guide strand in the 3′ UTR of the Renilla luciferase gene were used for RNAi and off-target activity assays, respectively. The RNAi activities (left bar graphs) and off-target activities (right bar graphs) of (B) siVIM-270 and its modified siRNAs and (C) siCLTC-2416 and its modified siRNAs were measured. Each upper sequence indicates the sequence of the passenger strand from 5′ to 3′; the lower sequence indicates the guide strand sequence from 3′ to 5′. Pink indicates positions or nucleotides modified with 2′-OMe. siRNA against green fluorescent protein (GFP) was used as the control siRNA (siCont). Each reporter assay was performed at concentrations of 0.0005, 0.005, 0.05, 0.5, or 5 nM siRNA. The horizontal bars indicate the relative luciferase activity (relative luc act). Results are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three independent experiments.

The 2′-OMe modifications were sequentially introduced from nucleotide 2–11 in siVIM-270 and to nucleotide 8 in siCLTC-2416. The RNAi activities of both siVIM-270 and siCLTC-2416 were similar and obviously high, even when 2′-OMe was introduced into any position in their seed regions (IC50s were 11–46 and 4–18 pM, respectively) (Figure 2B,C and Supporting Information Table S1). However, the 2′-OMe modifications showed clear effects on the off-target activities. The off-target activities of unmodified siVIM-270 and siCLTC-2416 gradually decreased along with the increase of 2′-OMe-modified nucleotides from position 2–5, then reached a plateau, and the off-target activities increased gradually after position 5 (Figure 2B,C and Supporting Information Table S1).

2.2. Functionally Different Effects of the 2′-OMe Modifications of Nucleotides 2–5 and 6–8 in the siRNA Seed Region on RNAi and Off-Target Activities

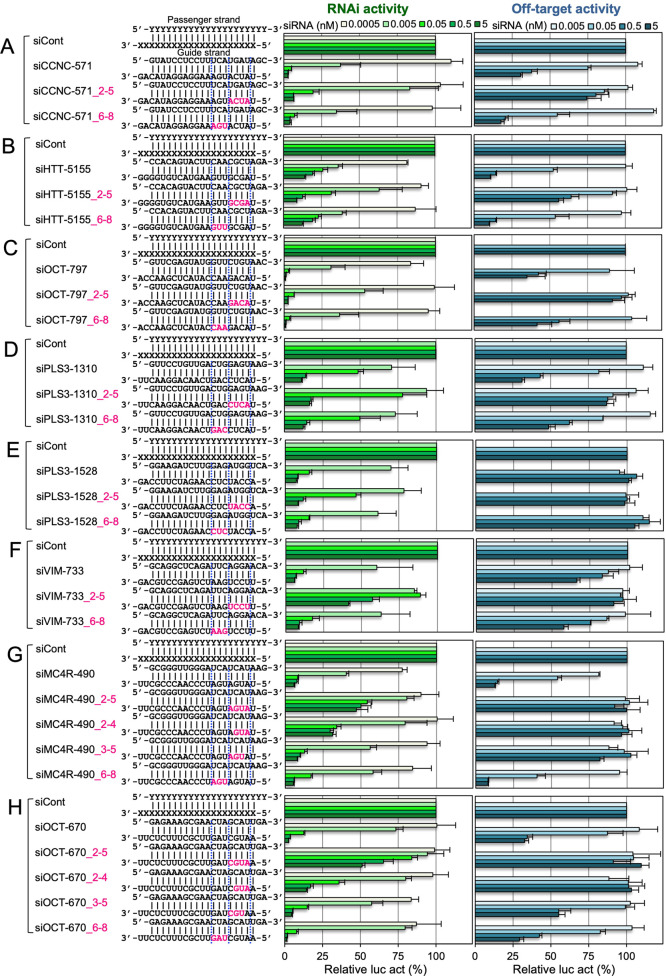

To investigate the functional differences of nucleotides 2–5 and 6–8, the RNAi and off-target activities of siRNAs with 2′-OMe modifications at either position were compared in detail. The RNAi activity of siVIM-270_2-5 showed no substantial loss compared to that of unmodified siVIM-270, and siVIM-270_6-8/siVIM-270_7-8 showed levels of RNAi activities similar to the unmodified siVIM-270. The off-target activity of siVIM-270_2-5 was almost completely eliminated, but those of both siVIM-270_6-8 and siVIM-270_7-8 were similar to that of unmodified siVIM-270. siVIM-270_2-8 exhibited intermediate RNAi and off-target activities (Figure 2B and Supporting Information Table S1). The RNAi activity of siCLTC-2416_2-5 was also only slightly reduced compared to that of unmodified siCLTC-2416, but its off-target activity was greatly reduced (Figure 2C and Supporting Information Table S1). The off-target activity of siCLTC-2416_2-8 was intermediate between siCLTC-2416_2-5 and siCLTC-2416_7-8, although very close to that of siCLTC-2416_7-8. We further investigated the effects of 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 and 6–8 using eight additional class I siRNAs: siCCNC-571, siHTT-5155, siOCT-797, siPLS3-1310, siPLS3-1528, siVIM-733, siMC4R-490, and siOCT-670 (Supporting Information Table S2). The 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 evidently reduced off-target effects compared to their unmodified ones in most of all siRNAs. These modifications showed almost no or slight effects on the RNAi activities of siCCNC-571, siHTT-5155, siOCT-797, siPLS3-1310, and siPLS3-1528 (Figure 3 and Supporting Information Table S1). However, the RNAi effects of siVIM-733, siMC4R-490, and siOCT-670 were severely reduced. Even in these cases, when the 2′-OMe modifications were introduced at positions 2–4 or 3–5, the RNAi activities of siMC4R-490 and siOCT-670 were drastically recovered. The results of these 10 class I siRNAs revealed that the 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 (or 3 among 4 nucleotides at positions 2–5) are sufficient to inhibit the off-target effect without affecting the substantial RNAi activity.

Figure 3.

Effects of 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5, 6–8 (7–8), or both on RNAi and off-target activities. RNAi (left bar graphs) and off-target activities (right bar graphs) of (A) siCCNC-571, (B) siHTT-5155, (C) siOCT-797, (D) siPLS3-1310, (E) siPLS3-1528, (F) siVIM-733, (G) siMC4R-490, and (H) siOCT-670 and their modified siRNAs. Each upper sequence indicates the sequence of the passenger strand from 5′ to 3′; the lower sequence indicates the guide strand sequence from 3′ to 5′. Pink indicates the positions or nucleotides modified with 2′-OMe. siRNA against GFP was used as control siRNA (siCont). Each reporter assay was performed at the concentrations indicated. The horizontal bars indicate relative luciferase activity (relative luc act). Results are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three independent experiments.

We also investigated the effects of 2′-OMe modifications in class II and III siRNAs. The siVIM-333, siGRK4-189, siVM-602, siFLT3-2493, and siH3FA-73 are class II siRNAs, and the siVIM-491, siKRAS-25, siBRCA2-1104, siGNAQ-616, and siTGFBR2-1648 are class III (Supporting Information Table S2). The 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 in almost all of them reduced both RNAi and off-target activities compared to those of unmodified siRNAs, but 2′-OMe modifications at positions 6–8 enhanced both RNAi and off-target activities (Supporting Information Figures S1 and S2 and Table S3).

These findings suggest that nucleotides 2–5 and 6–8 have different functions. The 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 (or 3–5/2–4) function to reduce the off-target activities without inducing considerable effects on the RNAi activities. Such effects are clearly observed mainly in class I siRNAs probably because the RNAi activities of class I siRNAs are intrinsically strong. In class II and III siRNAs, the RNAi effects were explicitly reduced by siRNAs with 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5. However, the 2′-OMe modifications at positions 6–8 enhanced both RNAi and off-target activities, and these effects are obviously observed in class II and III siRNAs and ambiguous in class I siRNA since the RNAi effects of class I siRNAs are originally strong. The integrated results of each class of siRNA suggest that the 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 reduced the off-target effect by steric hindrance, but the 2′-OMe modifications at positions 6–8 caused an opposite effect on those at positions 2–5.

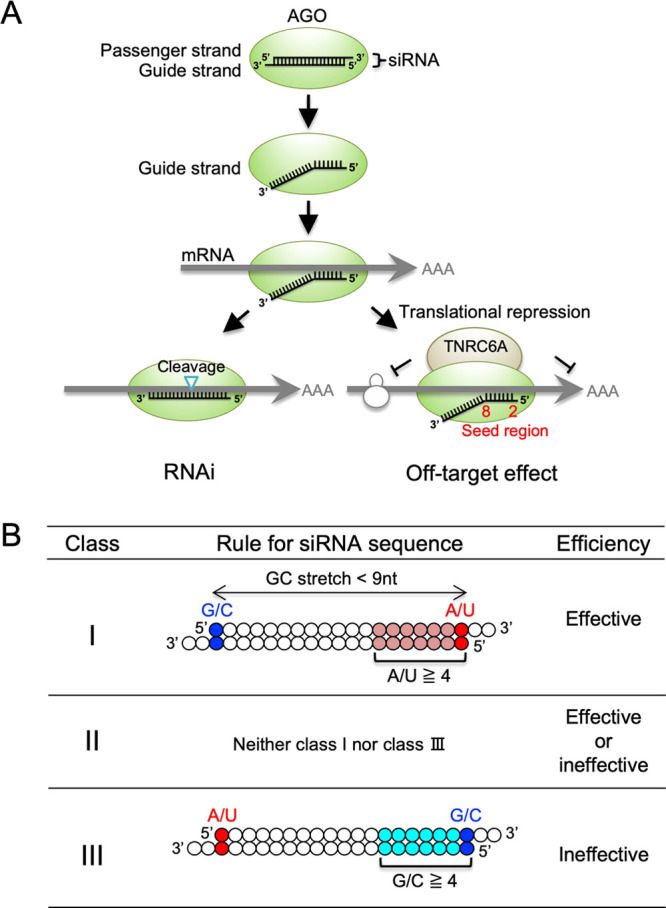

2.3. Effects of 2′-OMe Modifications at Positions 2–5 and 6–8 in the siRNA Seed Region on the Expression of Endogenous Genes

To investigate genome-wide off-target effects of siVIM-270 with 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 or 6–8, microarray analysis was performed. Unmodified and modified siVIM-270s were transfected into HeLa cells, separately, and total RNA was purified from the cells 1 day later and subjected to microarray analyses. The MA plots (M = intensity ratio, A = average intensity) of the microarray data indicated changes in the expression levels of the transcripts, and the cumulative distribution indicated the average fold changes of the transcripts with SM sequences in their 3′ UTRs compared to those with non-SM transcripts (Figure 4A–H). The expression level of the completely-matched (CM) target gene, vimentin, was obviously downregulated by any siRNA at the similar level, although siVIM-270_6-8 showed slightly stronger RNAi activity compared to other siRNAs (Figure 4I). The difference in the mean log2 fold changes of SM or non-SM transcripts of the siVIM-270 guide strand was calculated as an indicator of the degree of off-target effects (Figure 4J). The unmodified siVIM-270 and siVIM-270_6-8 showed significant off-target effects, but siVIM-270_2-5 and siVIM-270_2-8 exhibited no or little off-target effects. These results suggest that off-target effects on the endogenous genes are clearly prevented by 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5. In addition, it was noted that microarray data are almost linear with those of the quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) (Supporting Information Figure S3), indicating that the results of microarray analysis and those of the qRT-PCR are essentially identical to each other.

Figure 4.

Microarray analysis for the expression of the target vimentin gene and SM off-target genes of siVIM-270. (A–D) MA plots of the microarray date using the cells transfected with unmodified siVIM-270, siVIM-270_2-5, siVIM-270_6-8, and siVIM-270_6-8. The vertical bars indicate log2 fold changes of signal intensities in each sample to those of mock transfection (M value), and the horizontal bars indicate the averaged log10 signal intensities of mock and each siRNA transfection (A value). The dark-blue dots indicate the transcripts with SM sequences, and the light blue dots indicate the other transcripts. The pink arrowheads indicate vimentin. (E–H) Cumulative distributions. The horizontal bars indicate the M values of (A), and the vertical bars indicate the cumulative fractions of transcripts. The red lines indicate the cumulative curves of SM transcripts, and the black lines indicate the cumulative curves of the other non-SM transcripts. The downregulation of SM transcripts is shown by the fold changes in the expression of SM transcripts compared to that of the other non-SM transcripts. Each p-value was determined by the Wilcoxon rank sum test. (I) Expression levels of the target vimentin gene by the transfection of unmodified siVIM-270 or 2′-OMe-modified siVIM-270s. The horizontal bar indicates the signal intensity of the vimentin gene relative to the mock sample. (J) Seed-dependent off-target effects of unmodified siVIM-270 or 2′-OMe-modified siVIM-270s. The horizontal bar indicates the mean log2 fold change of the off-target transcripts in the cells transfected with unmodified siVIM-270 or 2′-OMe-modified siVIM-270s. Each p-value was determined by the Wilcoxon rank sum test (*p < 0.01). n.s., not significant.

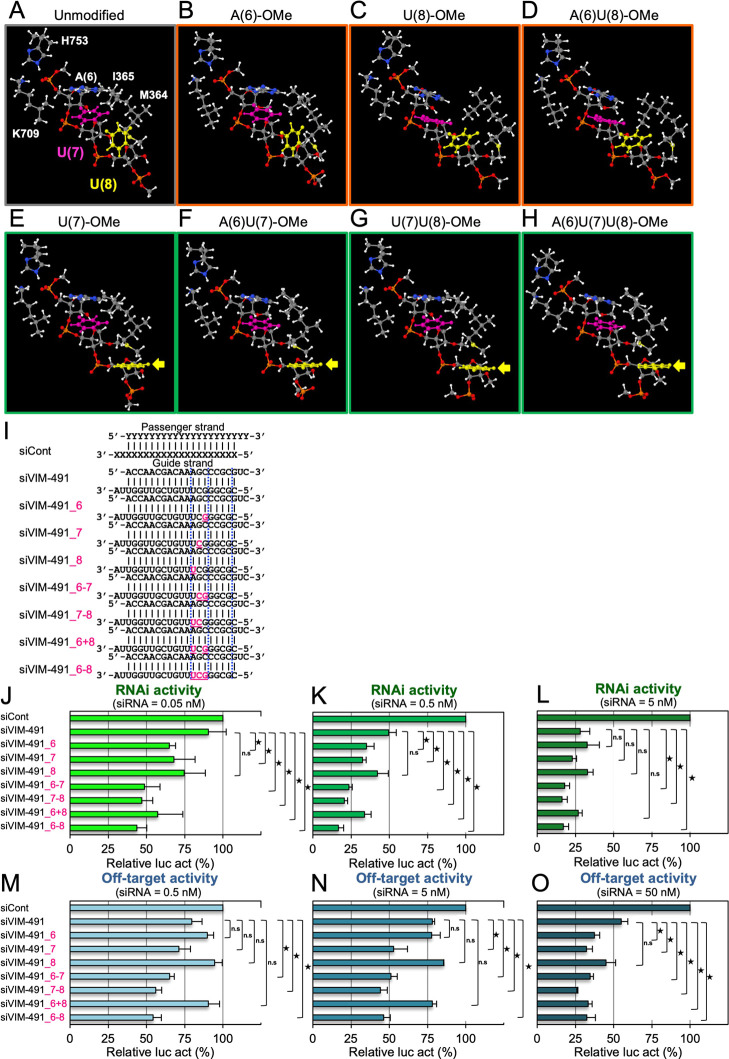

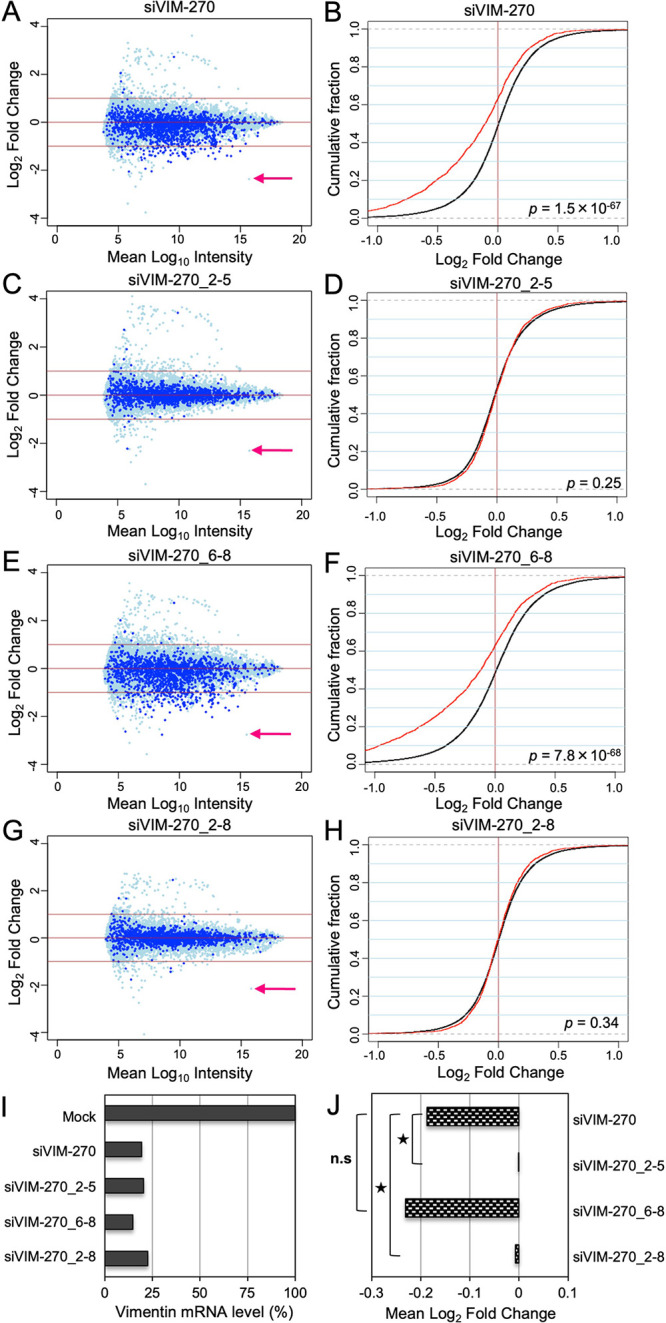

2.4. Computational Simulation of the Mechanism for Enhancing RNAi/Off-Target Activities by 2′-OMe Modifications at Positions 6–8

To reveal the mechanism by which 2′-OMe modifications at positions 6–8 enhance RNAi and off-target activities, we computationally simulated 2′-OMe-modified RNA structures on the AGO protein using density functional theory (DFT) at the ωB97X-D/6-31G(d) level. The unmodified 5′-AUU-3′ RNA structure {nucleotides 6–8 [A(6), U(7), and U(8)] of the guide RNA} on the human AGO protein reported by Schirle et al.38 was used, with side chains of His (H753), Lys (K709), Met (M364), and Ile (I365) residues (PDB: 4W5O). The AGO protein organizes the seed region by forming hydrogen bonds with the phosphate backbone at positions 3–6 of the guide RNA.30,38 The residues which form hydrogen bonds with the phosphate at position 6 are H753 and K709. Therefore, in the current computational system, these two residues, H753 and K709, were included with their Cα atoms being fixed such that the organization scheme at positions 3–6 of the guide RNA by the AGO protein is reflected in the current calculations. Furthermore, in the current system, the residues M364 and I365 were included to take account of the influence of helix-7. Full geometry optimization was performed with only the Cα atoms of H753 and K709 being fixed (Figure 5A). The same procedure was applied to single-stranded RNA structures in which the sugars of A(6), U(7), U(8), A(6)U(7), A(6)U(8), U(7)U(8), or A(6)U(7)U(8) were modified with 2′-OMe (Figure 5B–H).

Figure 5.

Computational simulation of RNA structures with 2′-OMe modifications at nucleotides 6–8. (A–H) 5′-AUU-3′ RNA structures of (A) unmodified siRNA and siRNAs with 2′-OMe modification at the (B) A(6), (C) U(8), (D) A(6)U(8), (E) U(7), (F) A(6)U(7), (G) U(7)U(8), or (H) A(6)U(7)U(8) nucleotides of the guide RNA with His (H753), Lys (K709), Met (M364), and Ile (I365) residues. The structures in the figures (A–H) are aligned to superimpose C5′, C4′, C3′, and O3 atoms of U(7) such that the differences in the conformations in (A–H) can be seen adequately. Geometry optimization was done with only the Cα atoms of H753 and K709 fixed. The base parts of U(7) and U(8) are indicated in pink and yellow, respectively. In (B–D), U(8) is orthogonal to U(7). In (E–H), U(8) is aligned such that the hydrogen-bonding interaction may be formed with target/off-target mRNA. (I) Sequence of siVIM-491 and its modified siRNAs. Each upper sequence indicates the sequence of the passenger strand from 5′ to 3′; the lower sequence indicates the guide strand sequence from 3′ to 5′. Pink indicates positions or nucleotides modified with 2′-OMe. siRNA against GFP was used as control siRNA (siCont). The results of reporter assays are separately shown for each siRNA concentration: (J) 0.05, (K) 0.5, or (L) 5 nM siRNA for RNAi activities and (M) 0.5, (N) 5, or (O) 50 nM siRNA for off-target activities. The horizontal bars indicate relative luciferase activity (relative luc act). Results are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three independent experiments. Each p-value was determined by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05). n.s., not significant.

After the geometry optimization, van der Waals interactions with the hydrophobic side chains of M364 and I365 appeared to impact the directions of A(6) and U(7) bases such that the formation of base pairs may be possible between the guide RNA and target/off-target mRNAs. This comes out in the glycosyl angles (χ dihedral angles) of the RNAs, which are summarized in Supporting Information Table S4. As shown in Table S4, the χ dihedral angles of A(6), U(7), and U(8) of unmodified RNA (Figure 5A) are 209.8, 223.7, and 272.0°, respectively. The χ dihedral angles of A(6) and U(7) of unmodified RNA are close to, but that of U(8) is rather larger than the average χ value of double-helical A-RNA (198.2°).39 In the 2′-OMe modified RNA structures (Figure 5–H and Supporting Information Table S4), these χ dihedral angles of A(6) and U(7) tend to decrease, being closer to the average χ value of double-helical A-RNA (198.2°).39 It is noteworthy that in RNA structures with the 2′-OMe modification in U(7), including U(7) (Figure 5E), A(6)U(7) (Figure 5F), U(7)U(8) (Figure 5G), and A(6)U(7)U(8) (Figure 5H), the methyl group of the 2′-OMe of U(7) creates van der Waals interaction with the U(8) base in addition to that by M364, which results in the χ dihedral angle of U(8) being 202°–207° (Supporting Information Table S4) which is suitable for base-pairing with target/off-target mRNAs. However, in the RNA structures with 2′-OMe modification at positions other than A(7), such as A(6) (Figure 5B), U(8) (Figure 5C), or A(6)U(8) (Figure 5D), U(8) was positioned orthogonal to U(7), with χ of U(8) being larger than ∼230°. In these cases, base pairings between U(7)/U(8) nucleotides in the guide RNA and target/off-target mRNAs are considered to be difficult. Thus, 2′-OMe modification at U(7) may support the U(8) direction easy to base-pair the target and off-target mRNAs.

Here, in the current calculations, DFT at the ωB97X-D/6-31G(d) level of theory was employed to reveal the impact of 2′-OMe modifications at positions 6–8. Large-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using molecular mechanical (MM) force field have recently been applied to RNA dynamics40 including a system of chemically modified siRNA and AGO protein.41 MD simulations with the MM force field are useful to describe dynamical features of biological systems. In the current calculations, we reveal the impact of 2′-OMe modifications at positions 6–8 in the seed region with the AGO protein by means of geometry optimization using DFT at the ωB97X-D/6-31G(d) level, which is known as appropriate to assess van der Waals interactions within large systems.42

The structural analyses revealed that part of the seed region of the single-stranded guide RNA on the human AGO protein is organized in a helical conformation, and its base stacking is interrupted by a kink between nucleotides 6 and 7.30,43−46 This kink is promoted by the helix-7 domain, including M364 and I365 residues of human AGO2, by inserting helix-7 between nucleotides 6 and 7. Thus, helix-7 creates a steric barrier to base pairing beyond nucleotide 5, namely, positions 6–8. However, the crystal structures of the guide–target duplex on the AGO protein show that helix-7 shifts to dock into the minor groove of the guide–target duplex in stable pairing. It is suggested that helix-7 may position the 3′ end of the guide strand for pairing to incoming RNAs. Thus, nucleotides 2–5 remain stable and immobile on the surface of the AGO protein in both single-stranded and double-stranded forms. Furthermore, the single-molecule analyses for base pairing between guide RNA and seed-paired target RNA on the mammalian AGO protein revealed that mismatches in nucleotides 2–5 of guide RNA are far more sensitive than those in nucleotides 6–8.47,48 These prior studies suggest that base pairing on AGO shows higher sensitivity to conformation changes in nucleotides 2–5 than to those in nucleotides 6–8. Thus, the 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 disturb the steady loading onto the AGO protein via steric hindrance, resulting in the inhibition of base pairing with target/off-target mRNAs. By contrast, the conformation of nucleotides 6–8 is flexible and easy to be changed by the interaction with helix-7; thus, 2′-OMe modifications at positions 6–8 have little or no effect on base pairing and may dynamically interact with target/off-target mRNAs to enhance the base-pairing stability.

2.5. Experimental Validation for the Enhancement of RNAi/Off-Target Activities by the 2′-OMe Modification of Nucleotide 7

Computational validation suggested that the 2′-OMe modification of the nucleotide 7 produces the largest effect in terms of base pairing with target/off-target mRNAs. We then validated the result experimentally using siVIM-491 (Figure 5I). The effects of 2′-OMe modifications at positions 6–8 on RNAi/off-target activities were clearly observed by siVIM-491 because its activities were intrinsically weak (Supporting Information Figure S2A). The results of the RNAi/off-target activities were compared at each concentration of siRNA. When the siRNA concentrations were at 0.05 (Figure 5J) and 0.5 nM (Figure 5K), siVIM-491_6 and siVIM-491_7 significantly increased RNAi activities compared to unmodified siVIM-491, but siVIM-491_8 did not. When two or three 2′-OMe modifications were simultaneously introduced into siRNAs (siVIM-491_6-7, siVIM-491_7-8, siVIM-491_6+8, and siVIM-491_6-8), RNAi activities were also significantly enhanced. However, when the siRNA concentration was increased to 5 nM (Figure 5L), clear differences in RNAi activities in siVIM-491_6, siVIM-491_7, and siVIM-491_8 were not observed, and siVIM-491_6-7, siVIM-491_7-8, and siVIM-491_6-8 exhibited significant RNAi activities. As for the off-target activity, siRNAs containing 2′-OMes at least at position 7 (siVIM-491_6-7, siVIM-491_7-8, or siVIM-491_6-8) significantly increased the off-target activities at 0.5 nM siRNA (Figure 5M), and siVIM-491_7 also additively increased the off-target activity at 5 nM siRNA (Figure 5N). When siRNA concentration was 50 nM, siVIM-491_6 also increased the off-target activity (Figure 5O). Thus, these results clearly suggest that 2′-OMe modification at position 7 is the most effective modification for RNAi/off-target activities, and 2′-OMe modification at position 6 contributed to the secondary highest effect, but 2′-OMe modification at position 8 exhibited almost no effect.

We also validated the effects of 2′-OMe modification at position 7 in addition to positions 2–5 (siCLTC-2416_2-5) because the functions of the nucleotides at positions 2–5 and 6–8 appear to differ. Although unmodified siCLTC-2416 exhibited strong RNAi and off-target activities, the RNAi and off-target activities of siCLTC-2416_2-5 were reduced (Supporting Information Figure S4 and Table S1). The off-target activities of siCLTC-2416_2-6 and siCLTC-2416_2-5+7 were stronger than that of siCLTC-2416_2-5+8. Furthermore, the off-target activities of siCLTC-2416_2-7 and siCLTC-2416_2-5+7-8 were stronger than that of siCLTC-2416_2-5+6+8. The off-target activity of siCLTC-2416_2-8 was similar to those of siCLTC-2416_2-7 and siCLTC-2416_2-5+7-8. However, the RNAi activities of these 2′-OMe-modified siRNAs were similar to that of siCLTC-2416_2-5, except for siCLTC-2416_2-5+8. Thus, these results suggest that the 2′-OMe modification at position 7, in addition to positions 2–5, is the most effective modification for influencing RNAi/off-target activities, similar to the results using siVIM-491 without 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 (Figure 5I–O). However, 2′-OMe modification at position 6 produced an effect similar to that at position 7 in the case of siCLTC-2416. A possible explanation is that the functions of nucleotides 6 and 7 may slightly differ according to the siRNA sequence. As for other chemical modifications, it was reported that altritol nucleic acids and 2′-fluorinated Northern-methanocarbacyclic (2′-F-NMC) modifications at position 7 are also best accommodated and tolerated with the highest performance for the reduction of target gene expression.49,50

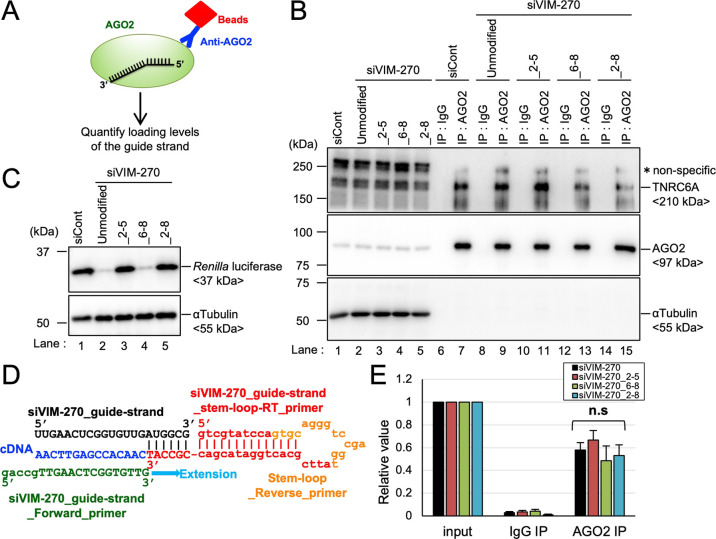

2.6. Effects of 2′-OMe Modifications on the AGO Loading Levels of siRNA Guide Strands

All classes of siRNAs with 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 showed strongly reduced off-target activities. By contrast, the same siRNAs with 2′-OMe modifications at positions 6–8 exhibited enhanced off-target activities (Figures 3 and 4, Supporting Information Figures S1 and S2). Thus, it was possible to assume that the amount of AGO-loaded guide strands with 2′-OMe modifications at positions 2–5 was lower compared to that with 2′-OMe modifications at positions 6–8. To investigate the effect of 2′-OMe modifications on AGO loading levels, we performed RNA and protein immunoprecipitation experiments using the anti-AGO2 antibody and quantified the amount of guide strands in the immunoprecipitates in the cells transfected with each siRNA (Figure 6A). The AGO2 protein and trinucleotide repeat containing 6A (TNRC6A) proteins, which interact with AGO (Figure 1A),51−53 were detected in the immunoprecipitates, indicating that the immunoprecipitation was successfully performed (Figure 6B). The Renilla luciferase protein was clearly observed in the lysate of cells transfected with control siRNA (siCont), siVIM-270_2-5, and siVIM-270_2-8, but luciferase levels were reduced by the transfection of unmodified siVIM-270 and siVIM-270_6-8 (Figure 6C), consistent with the results of the reporter assay (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the qRT-PCR using stem-loop PCR primers specific for the siVIM-270 guide strand was performed (Figure 6D). The amount of guide strands in the immunoprecipitate was almost similar regardless of 2′-OMe modifications (Figure 6E). These results are consistent with our previous result of structural simulation35 that the 2′-OMe-modifications in the siRNA seed region did not affect the interaction with the AGO protein.

Figure 6.

Effects of the 2′-OMe modifications of the siRNA guide strand on AGO2 loading of the guide strand. (A) Schematic presentation of RNA and protein immunoprecipitation experiments. After immunoprecipitation, the AGO2 loading levels of the guide strand were quantified. (B) Western blot of input samples (lanes 1–5), immunoprecipitates with IgG (IgG-IP; lanes 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14), and immunoprecipitates with the anti-AGO2 antibody (AGO2-IP; lanes 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15). Unmodified siVIM-270 or modified siRNAs with 2′-OMe modification at positions 2–5, 6–8, or 2–8 were transfected into HeLa cells with a psiCHECK-VIM270-SM reporter construct and immunoprecipitated with the anti-AGO2 antibody or anti-mouse IgG antibody as a negative control. Endogenous TNRC6A, AGO2, and α-tubulin were detected with specific antibodies, respectively. (C) Western blot of Renilla luciferase in the input samples (lanes 1–5). α-Tubulin was detected as a control. (D) Schematic representation of stem-loop RT-PCR specific for the siVIM-270 guide strand. Black indicates the sequences of the siVIM-270 guide strand. Red and orange indicate the sequences of stem-loop reverse-transcription primers specific for the siVIM-270 guide strand. Blue indicates cDNA sequences generated by reverse transcription. Green indicates the sequences of forward PCR primers specific for the siVIM-270 guide strand. Orange indicates the sequences of reverse primers. Light blue indicates the orientations of extension using forward primers. (E) Results of quantification of the siVIM-270 guide strand in each fraction. The copy numbers were calculated via an absolute quantification method using standard curves of each synthesized siRNA and normalized to the copy numbers of the guide strand in each input fraction. siRNA against GFP was used as control siRNA (siCont). Results are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three independent experiments. Each p-value was determined by Student’s t-test. n.s., not significant.

Furthermore, in order to exclude the possibility of non-specific binding of siRNA with AGO2, the same binding assay was performed using AGO2-Y529E protein. AGO2-Y529E is impaired in siRNA binding by the substitution of tyrosine to glutamic acid at amino acid 529, which is located in the binding pocket of AGO2 with the 5′-end of the siRNA guide strand.54 The pFLAG/HA-empty, pFLAG/HA-AGO2, or pFLAG/HA-AGO2-Y529E expression construct was transfected into HeLa cells with siVIM-270 or siVIM-270_2-5, and immunoprecipitation was performed with the anti-FLAG antibody. The FLAG-AGO2 proteins were clearly detected in the immunoprecipitates, indicating that the immunoprecipitations were successfully performed (Supporting Information Figure S5A). The results of the qRT-PCR indicated that the amounts of guide strands in the immunoprecipitates were almost similar regardless of 2′-OMe modifications but were significantly reduced by AGO2-Y529E compared to AGO2-WT (Supporting Information Figure S5B). Therefore, it is considered that this binding assay certainly detects siRNAs whose 5′-ends were stably located in the binding pockets of AGO2 proteins without detecting nonspecific loading on the AGO protein. Thus, these results suggest that 2′-OMe modification had almost no effect on AGO loading.

3. Conclusions

We revealed that the siRNA seed region is composed of two differentially responsive domains to 2′-OMe modifications: nucleotides 2–5 and 6–8. This is the first report to show the differences of the functional machinery of these two domains; the 2′-OMe modifications at nucleotides 2–5 function to reduce the off-target activity due to steric hindrance without affecting on-target RNAi activity mainly in class I siRNA, but those at nucleotides 6–8 enhance both on-target and most of the off-target activities, especially in class III siRNA (Figure 7). Our computational simulation of 2′-OMe modification in each of the nucleotides 6–8 proposed the possibility that the nucleotide at position 7 exerts the strongest impact on base pairing with target/off-target mRNA. Then, we demonstrated that 2′-OMe modifications at positions 7 enhance RNAi/off-target activities. Furthermore, our immunoprecipitation experiment clearly revealed that none of the 2′-OMe modifications affected the AGO loading efficiencies of these 2′-OMe-modified siRNAs. Taken together, our studies could provide expanded knowledge for the therapeutic application of siRNA.

Figure 7.

Model of the functional mechanism of each siRNA. In the case of unmodified siRNA, the siRNA guide strand is stably loaded onto the AGO protein, and it induces an off-target effect for off-target mRNAs with seed complementarities and an RNAi effect for a target mRNA with perfect sequence complementarity. The siRNA guide strand with 2′-OMe of nucleotides 2–5 is also successfully loaded on AGO. However, the base pairing at positions 2–5 between guide RNA and off-target mRNAs causes steric hindrance, resulting in the inhibition of the off-target effect. As for RNAi, it is considered that base-pairing between nucleotides 6–21 and target mRNA is sufficient to induce RNAi. Even though 2′-OMes are introduced into nucleotides 6–8, these modifications do not induce steric hindrance on the AGO protein. Therefore, RNAi and off-target effects are induced by an almost similar manner as the unmodified siRNA. Furthermore, 2′-OMe modifications of nucleotides 6–8, especially nucleotide 7, enhance both RNAi and off-target effects.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Cell Culture

Human HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (FUJIFILM Wako, Osaka, Japan) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (BioWest, Nuaille, France) and a 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution (FUJIFILM Wako) at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

4.2. Chemical Synthesis of siRNA Duplexes

RNA oligonucleotides corresponding to the guide and passenger strands of each siRNA were chemically synthesized (Gene Design, Osaka, Japan; Shanghai Gene Pharma, Shanghai, China) and subsequently annealed to form endogenous siRNA duplexes. All siRNA sequences used in this study are summarized in Supporting Information Table S2.

4.3. Construction of CM and SM Luciferase Reporters

All of the reporter plasmids used in this study were constructed according to the procedures shown in our previous report35 and are listed in Supporting Information Tables S5 and S6. psiCHECK-CM and psiCHECK-SM reporter constructs were, respectively, used to test the RNAi and off-target effects of the corresponding siRNAs.

4.4. RNA Silencing Activity Assay for the Renilla Luciferase Gene

RNAi and off-target activities were measured using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), as shown in our previous report,35 except for using 0.01 μg of each psiCHECK construct. An siRNA called siGY441, which did not target any CM- and SM-reporter constructs, was used as an internal control.

The half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of the siRNAs were estimated using the following linear model.

A: concentration when the inhibitory efficiency is lower than 50%, B: concentration when the inhibitory efficiency is higher than 50%, C: inhibitory efficiency in B,D: inhibitory efficiency in A.

The IC50s are listed in Supporting Information Tables S1 and S3.

4.5. Microarray Analysis

A HeLa cell suspension (0.5 × 105 cells/mL) was inoculated into a well of a 24-well culture plate 1 day before transfection. The cells were transfected with 100 nM of each siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000. At 24 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested from three wells per sample. The total RNA was purified using FastGene RNA Premium Kit (NIPPON Genetics, Tokyo, Japan). Quality check of the total RNA and preparation of the microarray sample were performed as described in our previous report.35 RNA from mock-transfected cells treated with the transfection reagent in the absence of siRNA was used as a control, and the distributions of the signal intensities of the transcripts were normalized across all samples by quantile normalization.55 The results are shown in MA plots and cumulative accumulations.

4.6. Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNAs applied for microarray analysis were used for qRT-PCR. RNA from mock-transfected cells treated with the transfection reagent in the absence of siRNA was used as a control. An aliquot of total RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The mixture of synthesized cDNA, gene-specific primer sets, and KAPA SYBR Fast qPCR Kit (NIPPON Genetics) was subjected to the PCR. The levels of PCR products were monitored with a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed by the ΔΔCt method. The expression level of each sample was first normalized to the amount of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and then to the mock-transfection control. The used primer sets are listed in Supporting Information Table S7.

4.7. Computational Prediction of the Structure of Modified RNA

The Cartesian coordinates of the crystal structure (PDB ID: 4W5O) were used as the initial geometry for 5′-AUU-3′ RNAs in positions 6–8 from the 5′ end of the guide RNA loaded on the AGO protein. Met364, Ile365, Lys709, and His753 of the AGO protein were taken into account in the calculations, in which the main chains of these amino acid residues were replaced by methyl groups at the atoms bonded to Cα, and the terminal phosphates of 5′-AUU-3′ were capped with methyl groups (Supporting Information Figure S6). For modified 5′-AUU-3′ RNA, we introduced 2′-OMe modifications of all combinations at positions 6–8. Full geometry optimization with the Cα atoms of Lys709 and His753 being fixed was performed at the theoretical level of ωB97X-D/6-31G(d). All the calculations were done in the gas phase since we focused on the local interactions between the side chains of several residues of the AGO protein and the nucleotides 6–8 of the guide RNA in the current system. The χ dihedral angles of the RNAs are summarized in Supporting Information Table S4. The energies are listed in Supporting Information Table S8 together with all Cartesian coordinates.

4.8. Immunoprecipitation by the Anti-AGO2 Antibody

A HeLa cell suspension was plated into a 9 cm dish (1.0 × 106 cells/dish) 1 day before transfection. The cells were simultaneously transfected with 20 nM of each siRNA and 1 μg of psiCHECK-SM reporter construct using Lipofectamine 2000. The cells were harvested from four dishes per one sample, washed with PBS, and lysed in cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 4 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 0.5% NP-40, complete protease inhibitor, and 0.03 units RNase inhibitor) 24 h following transfection. For immunoprecipitation, 50 μL of Dynabeads Protein G (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was conjugated with 2.5 μL of the mouse anti-AGO2 antibody (1.0 mg/mL, FUJIFILM Wako) or 6.25 μL of mouse IgG (0.4 mg/mL, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) as a negative control by rotation at 4 °C for overnight. The cell lysates were then added to antibody-bound Dynabeads Protein G and rotated at 4 °C for 2 h. The beads were washed three times with the wash buffer (lysis buffer containing 300 mM NaCl) and twice with the lysis buffer. To elute the bound proteins with RNA, 100 μL of the 2 × SDS-PAGE sample buffer (4% (wt/vol) SDS, 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 12% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol, 20% (wt/vol) glycerol, and 0.01% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue) was added, and the beads were heated at 70 °C for 10 min. The Dynabeads were removed by using DynaMag (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Half of the eluted supernatant was subjected to western blotting, and the remaining was subjected to RNA extraction.

To investigate the nonspecific binding of siRNA on AGO2 protein, the cells were simultaneously transfected with 5 μg of pFLAG/HA-empty, pFLAG/HA-Ago2-WT, or pFLAG/HA-Ago2-Y529E constructed in our previous study56 and 20 nM of each siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000. 1 day after transfection, the cell lysates were prepared as shown above and incubated with 50 μl of Dynabeads Protein G conjugated with 2.5 μL of the mouse anti-FLAG antibody (1.0 mg/mL, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) by constant rotation at 4 °C for 2 h. Then, the following wash and elution steps were performed in the same manner as shown above.

4.9. Western Blot

The eluate of the immunoprecipitate was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to an Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) using the Mini Trans-Blot Cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in TBST (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween) supplemented with 5% Difco skimmed milk (FUJIFILM Wako). Blocked membranes were incubated with each of the primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight in TBST +5% skimmed milk or the Can Get Signal immunoreaction enhancer solution (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). Then, the membranes were washed three times for 10 min at room temperature with TBST and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the secondary antibodies. The primary and secondary antibodies are shown in Supporting Information Table S9. After being washed three times for 10 min in TBST at room temperature, the membrane was incubated with the ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare), and signals were detected by FUSION (VILBER, Collégien, France).

4.10. Quantification of siRNAs Loaded onto AGO2

ISOGEN (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) was added to the eluate of the immunoprecipitation by the anti-AGO2 antibody or mouse IgG. It was also added to 10% of the cell lysates as input samples. RNA extraction was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. An aliquot of RNA (80 ng) was reverse-transcribed using the stem-loop primer specific for each strand of siRNA with High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits. A mixture of the synthesized cDNA, siRNA-specific forward primer, and loop-specific reverse primer was subjected to PCR amplification using the KAPA SYBR Fast qPCR Kit. The levels of PCR products were monitored using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System, and the copy numbers of each sample were calculated using the absolute quantification method. To prepare the standard curve for each sample, each synthesized siRNA (0.00005–5 ng) was similarly reverse-transcribed. Each copy number from the immunoprecipitate was normalized to that in the input fraction. The primer sets are listed in Supporting Information Table S7.

Acknowledgments

The Gaussian 09 program package57 was used for all calculations. The simulations were carried out at the Center for Quantum Life Sciences and the Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki National Research Institutes. We thank Y. Natori and K. Saigo for helpful comments throughout this study. The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c06455.

Luciferase reporter assays of class II and III siRNAs, qRT-PCR, additional immunoprecipitation data and computational data, IC50 values, sequences of siRNA, χ dihedral angles of RNA, reporter construct and primer, total energy of 5′-AUU-3′ RNA with the AGO protein, and list of antibody information (PDF)

Author Contributions

Y.K. and K.U.-T. designed the study at first, and Y.K. and K.U.-T. discussed the methods, results, and the experimental plans. Y.K. performed the experiments. D.F., D.A., and M.A. performed computational simulation of 2′-OMe-modified RNA. The manuscript was drafted by K.U.-T., and Y.K. and K.U.-T. completed the manuscript. Y.K. and K.U.-T. were involved in reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by the grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan [26102713 and 16K14640 to K.U.-T.] and the grants provided from the Suzuken Memorial Foundation, Japan Health & Research Institute, the Japan Health Foundation, the Kurata Grant awarded by the Hitachi Global Foundation, and START JPMJST1915 to K.U.-T.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

The microarray Data (related Figure 4) have been deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with the data set identifier GSE 188314.

Supplementary Material

References

- Fire A.; Xu S.; Montgomery M. K.; Kostas S. A.; Driver S. E.; Mello C. C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806–811. 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamore P. D.; Tuschl T.; Sharp P. A.; Bartel D. P. RNAi: Double-Stranded RNA Directs the ATP-Dependent Cleavage of mRNA at 21 to 23 Nucleotide Intervals. Cell 2000, 101, 25–33. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E.; Caudy A. A.; Hammond S. M.; Hannon G. J. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature 2001, 409, 363–366. 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir S. M.; Lendeckel W.; Tuschl T. RNA interference is mediated by 21-and 22-nucleotide RNAs. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 188–200. 10.1101/gad.862301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketting R. F.; Fischer S. E. J.; Bernstein E.; Sijen T.; Hannon G. J.; Plasterk R. H. A. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 2654–2659. 10.1101/gad.927801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond S. M.; Boettcher S.; Caudy A. A.; Kobayashi R.; Hannon G. J. Argonaute2, a Link Between Genetic and Biochemical Analyses of RNAi. Science 2001, 293, 1146–1150. 10.1126/science.1064023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi N.; Zenno S.; Ueda R.; Ohki-Hamazaki H.; Ui-tei K.; Saigo K. Short-Interfering-RNA-Mediated Gene Silencing in Mammalian Cells Requires Dicer and eIF2C Translation Initiation Factors. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 41–46. 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Carmell M. A.; Rivas F. V.; Marsden C. G.; Thomson J. M.; Song J.-J.; Hammond S. M.; Joshua-Tor L.; Hannon G. J. Argonaute2 Is the Catalytic Engine of Mammalian RNAi. Science 2004, 305, 1437–1441. 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister G.; Landthaler M.; Patkaniowska A.; Dorsett Y.; Teng G.; Tuschl T. Human Argonaute2 Mediates RNA Cleavage Targeted by miRNAs and siRNAs. Mol. Cell. 2004, 15, 185–197. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas F. V.; Tolia N. H.; Song J.-J.; Aragon J. P.; Liu J.; Hannon G. J.; Joshua-Tor L. Purified Argonaute2 and an siRNA form recombinant human RISC. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 340–349. 10.1038/nsmb918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matranga C.; Tomari Y.; Shin C.; Bartel D. P.; Zamore P. D. Passenger-Strand Cleavage Facilitates Assembly of siRNA into Ago2-Containing RNAi Enzyme Complexes. Cell 2005, 123, 607–620. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand T. A.; Petersen S.; Du F.; Wang X. Argonaute2 Cleaves the Anti-Guide Strand of siRNA during RISC Activation. Cell 2005, 123, 621–629. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata T.; Seitz H.; Tomari Y. Structural determinants of miRNAs for RISC loading and slicer-independent unwinding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 953–960. 10.1038/nsmb.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoda M.; Kawamata T.; Paroo Z.; Ye X.; Iwasaki S.; Liu Q.; Tomari Y. ATP-dependent human RISC assembly pathways. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 17–23. 10.1038/nsmb.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novina C. D.; Sharp P. A. The RNAi revolution. Nature 2004, 430, 161–164. 10.1038/430161a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui-Tei K.; Naito Y.; Takahashi F.; Haraguchi T.; Ohki-Hamazaki H.; Juni A.; Ueda R.; Saigo K. Guidelines for the selection of highly effective siRNA sequences for mammalian and chick RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 936–948. 10.1093/nar/gkh247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noland C. L.; Ma E.; Doudna J. A. siRNA Repositioning for Guide Strand Selection by Human Dicer Complexes. Mol. Cell 2011, 43, 110–121. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur J. G.; Tomari Y. Dicer is dispensable for asymmetric RISC loading in mammals. RNA 2012, 18, 24–30. 10.1261/rna.029785.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noland C. L.; Doudna J. A. Multiple sensors ensure guide strand selection in human RNAi pathways. RNA 2013, 19, 639–648. 10.1261/rna.037424.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank F.; Sonenberg N.; Nagar B. ′-nucleotide base-specific recognition of guide RNA by human AGO2. Nature 2010, 465, 818–822. 10.1038/nature09039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. L.; Bartz S. R.; Schelter J.; Kobayashi S. V.; Burchard J.; Mao M.; Li B.; Cavet G.; Linsley P. S. Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 635–637. 10.1038/nbt831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scacheri P. C.; Rozenblatt-Rosen O.; Caplen N. J.; Wolfsberg T. G.; Umayam L.; Lee J. C.; Hughes C. M.; Shanmugam K. S.; Bhattacharjee A.; Meyerson M.; Collins F. S. Short interfering RNAs can induce unexpected and divergent changes in the levels of untargeted proteins in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 1892–1897. 10.1073/pnas.0308698100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B. P.; Burge C. B.; Bartel D. P. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 2005, 120, 15–20. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim L. P.; Lau N. C.; Garrett-Engele P.; Grimson A.; Schelter J. M.; Castle J.; Bartel D. P.; Linsley P. S.; Johnson J. M. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature 2005, 433, 769–773. 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X.; Ruan X.; Anderson M. G.; McDowell J. A.; Kroeger P. E.; Resik S. W.; Shen Y. siRNA-mediated off-target gene silencing triggered by a 7 nt complementation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 4527–4535. 10.1093/nar/gki762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham A.; Anderson E. M.; Reynolds A.; Ilsley-Tyree D.; Leake D.; Fedorov Y.; Baskerville S.; Maksimova E.; Robinson K.; Karpilow J.; Marshall W. S.; Khvorova A. 3′ UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off-targets. Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 199–204. 10.1038/nmeth854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. L.; Burchard J.; Schelter J.; Chau B. N.; Cleary M.; Lim L.; Linsley P. S. Widespread siRNA “off-target” transcript silencing mediated by seed region sequence complementarity. RNA 2006, 12, 1179–1187. 10.1261/rna.25706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimson A.; Farh K. K.-H.; Johnston W. K.; Garrett-Engele P.; Lim L. P.; Bartel D. P. MicroRNA Targeting Specificity in Mammals: Determinants beyond Seed Pairing. Mol. Cell. 2007, 27, 91–105. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkayam E.; Kuhn C.-D.; Tocilj A.; Haase A. D.; Greene E. M.; Hannon G. J.; Joshua-Tor L. The Structure of Human Argonaute-2 in Complex with miR-20a. Cell 2012, 150, 100–110. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirle N. T.; MacRae I. J. The Crystal Structure of Human Argonaute2. Science 2012, 336, 1037–1040. 10.1126/science.1221551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui-Tei K.; Naito Y.; Nishi K.; Juni A.; Saigo K. Thermodynamic stability and Watson–Crick base pairing in the seed duplex are major determinants of the efficiency of the siRNA-based off-target effect. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 7100–7109. 10.1093/nar/gkn902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito Y.; Yoshimura J.; Morishita S.; Ui-Tei K. siDirect 2.0: updated software for designing functional siRNA with reduced seed-dependent off-target effect. BMC Bioinf. 2009, 10, 392. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. L.; Burchard J.; Leake D.; Reynolds A.; Schelter J.; Guo J.; Johnson J. M.; Lim L.; Karpilow J.; Nichols K.; Marshall W.; Khvorova A.; Linsley P. S. Position-specific chemical modification of siRNAs reduces ″off-target″ transcript silencing. RNA 2006, 12, 1197–1205. 10.1261/rna.30706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramsen J. B.; Pakula M. M.; Hansen T. B.; Bus C.; Langkjær N.; Odadzic D.; Smicius R.; Wengel S. L.; Chattopadhyaya J.; Engels J. W.; Herdewijn P.; Wengel J.; Kjems J. A screen of chemical modifications identifies position-specific modification by UNA to most potently reduce siRNA off-target effects. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 5761–5773. 10.1093/nar/gkq341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iribe H.; Miyamoto K.; Takahashi T.; Kobayashi Y.; Leo J.; Aida M.; Ui-Tei K. Chemical Modification of the siRNA Seed Region Suppresses Off-Target Effects by Steric Hindrance to Base-Pairing with Targets. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 2055–2064. 10.1021/acsomega.7b00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Zhang L.; Zhang J.; Wang X.; Ye K.; Xi Z.; Du Q.; Liang Z. Single modification at position 14 of siRNA strand abolishes its gene-silencing activity by decreasing both RISC loading and target degradation. BMC Bioinf. 2013, 27, 4017–4026. 10.1096/fj.13-228668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S. M.; Sousa J.; Vangjeli L.; Hassler M. R.; Echeverria D.; Knox E.; Turanov A. A.; Alterman J. F.; Khvorova A. 2′-O-Methyl at 20-mer Guide Strand 3′ Termini May Negatively Affect Target Silencing Activity of Fully Chemically Modified siRNA. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 21, 266–277. 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirle N. T.; Sheu-Gruttadauria J.; MacRae I. J. Structural basis for microRNA targeting. Science 2014, 346, 608–613. 10.1126/science.1258040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y.; Fujii S.; Hiroaki H.; Sakata T.; Tanaka T.; Uesugi S.; Tomita K.; Kyogoku Y. A’-form RNA double helix in the single crystal structure of r(UGAGCUUCGGCUC). Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 949–955. 10.1093/nar/27.4.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šponer J.; Bussi G.; Krepl M.; Banáš P.; Bottaro S.; Cunha R A.; Gil-Ley A.; Pinamonti G.; Poblete S.; Jurečka P.; et al. RNA Structural Dynamics as Captured by Molecular Simulations: A Comprehensive Overview. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4177–4338. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harikrishna S.; Pradeepkumar P. I. Probing the binding interactions between chemically modified siRNAs and Human Argonaute 2 using microsecond molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 883–896. 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maranzana A.; Giordana A.; Indarto A.; Tonachini G.; Barone V.; Causà M.; Pavone M. Density functional theory study of the interaction of vinyl radical, ethyne, and ethene with benzene, aimed to define an affordable computational level to investigate stability trends in large van der Waals complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 244306. 10.1063/1.4846295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K.; Weinberg D. E.; Bartel D. P.; Patel D. J. Structure of yeast Argonaute with guide RNA. Nature 2012, 486, 368–374. 10.1038/nature11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K.; Ascano M.; Gogakos T.; Ishibe-Murakami S.; Serganov A. A.; Briskin D.; Morozov P.; Tuschl T.; Patel D. J. Eukaryote-specific insertion elements control human Argonaute slicer activity. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 1893–1900. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faehnle C. R.; Elkayam E.; Haase A. D.; Hannon G. J.; Joshua-Tor L. The making of a slicer: activation of human Argonaute-1. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 1901–1909. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klum S. M.; Chandradoss S. D.; Schirle N. T.; Joo C.; MacRae I. J. Helix-7 in Argonaute2 shapes the microRNA seed region for rapid target recognition. EMBO J. 2018, 37, 75–88. 10.15252/embj.201796474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon W. E.; Jolly S. M.; Moore M. J.; Zamore P. D.; Serebrov V. Single-molecule imaging reveals that Argonaute reshapes the binding properties of its nucleic acid guides. Cell 2015, 162, 84–95. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandradoss S. D.; Schirle N. T.; Szczepaniak M.; MacRae I. J.; Joo C. A dynamic search process underlies microRNA targeting. Cell 2015, 162, 96–107. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P.; Degaonkar R.; Guenther D. C.; Abramov M.; Schepers G.; Capobianco M.; Jiang Y.; Harp J.; Kaittanis C.; Janas M. M.; et al. Chimeric siRNAs with chemically modified pentofuranose and hexopyranose nucleotides: altritol-nucleotide (ANA) containing GalNAc–siRNA conjugates: in vitro and in vivo RNAi activity and resistance to 5′-exonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 4028–4040. 10.1093/nar/gkaa125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akabane-Nakata M.; Erande N. D.; Kumar P.; Degaonkar R.; Gilbert J. A.; Qin J.; Mendez M.; Woods L. B.; Jiang Y.; Janas M. M. siRNAs containing 2′-fluorinated Northern-methanocarbacyclic (2′-F-NMC) nucleotides: in vitro and in vivo RNAi activity and inability of mitochondrial polymerases to incorporate 2′-F-NMC NTPs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 2435–2449. 10.1093/nar/gkab050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister G.; Landthaler M.; Peters L.; Chen P. Y.; Urlaub H.; Luhrmann R.; Tuschl T. Identification of novel argonaute-associated proteins. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 2149–2155. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian S. L.; Li S.; Abadal G. X.; Pauley B. A.; Fritzler M. J.; Chan E. K. L. The C-terminal half of human Ago2 binds to multiple GW-rich regions of GW182 and requires GW182 to mediate silencing. RNA 2009, 15, 804–813. 10.1261/rna.1229409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto K.; Wakiyama M.; Yokoyama S. Mammalian GW182 contains multiple Argonaute-binding sites and functions in microRNA-mediated translational repression. RNA 2009, 15, 1078–1089. 10.1261/rna.1363109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüdel S.; Wang Y.; Lenobel R.; Körner R.; Hsiao H. H.; Urlaub H.; Patel D. J.; Meister G. Phosphorylation of human Argonaute proteins affects small RNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 2330–2343. 10.1093/nar/gkq1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad B. M.; Irizarry R. A.; Gautier L.; Wu Z.. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor; Gentleman R., Carey V., Huber W., Irizarry R., Dudoit S., Eds.; Springer: New York, 2005; pp 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi K.; Takahashi T.; Suzawa M.; Miyakawa T.; Nagasawa T.; Ming Y.; Tanokura M.; Ui-Tei K. Control of the localization and function of a miRNA silencing component TNRC6A by Argonaute protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 9856–9873. 10.1093/nar/gkv1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision E.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.