Abstract

Malaria affects about half of the world's population. The sub-Saharan African region is the most affected. Plant natural products have been a major source of antimalarial drugs; the first (quinine) and present (artemisinin) antimalarials are of natural product origin. Some secondary metabolites demonstrate adjuvant antioxidant effects and selective activity. The focus of this study was to investigate the anti-plasmodial activity, cytotoxicities and antioxidant properties of eight (8) Ghanaian medicinal plants. The anti-plasmodial activity was determined using the SYBR green assay and the tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay (MTT) was employed to assess cytotoxicity of extracts to human RBCs and HL-60 cells. Antioxidant potential of plant extracts was evaluated using Folin-Ciocalteu and superoxide dismutase assays. Phytochemical contstituents of the plant extracts were also assessed. All the extracts demonstrated anti-plasmodial activities at concentrations <50 μg/ml. Parkia clappertoniana and Terminalia ivorensis elicited the strongest anti-plasmodial activities with 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of 1.13 μg/ml and 0.95 μg/ml, respectively. This is the first report on anti-plasmodial activities of Baphia nitida, Tabernaemontana crassa and Treculia Africana. T. Africana showed moderate anti-plasmodial activity with IC50 value of 6.62 µg/mL. Extracts of P. clappertoniana, T. Africana and T. ivorensis (0.4 mg/mL) showed >50% antioxidant effect (SOD). The extracts were not cytotoxicity towards RBCs at the concentration tested (200 μg/ml) but were weakly cytotoxic to HL-60 cell. Selectivity indices of most of the extracts were greater than 10. Our results suggest that most of the plant extracts have strong anti-plasmodial activity and antioxidant activity which warrants further investigations.

Keywords: antioxidant, anti-plasmodial, malaria, medicinal plants, phenolic content

Introduction

Malaria is a blood parasitic disease caused by various plasmodium species; the predominant ones been P. falciparum and P. malariae. The burden of disease and mortalities are disproportionately high in low-income countries. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 228 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide in 2018, and nineteen countries in sub-Saharan Africa and India accounted for about 85% of the global malaria burden. 1 Chemotherapy remains the main available treatment regimen, as studies are yet to produce malaria vaccine for protection against the parasite. The Plasmodium parasites like most microorganisms develop resistance over periodic drug therapy. Parasites’ resistance to chloroquine and recently arteminisins have been reported.2,3 The first chloroquine resistance to P. falciparum was recorded in 1978 in nonimmune travelers from Kenya and Tanzania, followed by a wide-spread resistance across the coastal inland areas and most parts of Africa by 1983.3,4 Quite recently, reports from Asian countries including Cambodia, China, Myanmar and Vietnam showed resistance to artemisinin, the current first-line drug used as antimalarial treatment regimen 3 in several countries including Ghana. Thus, drug resistance is a major challenge to malaria control, hence it is imperative to search for alternative and more potent antimalarials to replace the current drugs whenever drug resistance becomes widespread.

Plant natural products have been enormous reservoirs for antimalarial drug discovery; earlier successful efforts led to the discovery of the first antimalarial drug, quinine and, subsequently chloroquine, mefloquine and artemisinin. 5 The tropical flora has an enormous diversity of plants and yet to be elucidated natural products. Ghana, a tropical West African country is home to over 1000 medicinal plants, and more than 100 plants have been reported in ethnobotanical studies as therapies for traditional malaria treatment.6,7 Previous studies have reported good anti-plasmodial activities in several plants.8,9

Oxidative damage is a major pathological consequence of malaria infections. Vital organs of the body are affected by oxidative stress, resulting in changes such as hepatomegaly, splenomegaly as well as endothelial and cognitive damages. Antimalarials currently available on the market often leave traces of these damages after treatment. 10 Several medicinal plants have been reported to have antioxidant properties.11–13 Phenolics are plant components that could have good antioxidant properties. Therefore, we investigated the in vitro antimalarial and phenolic content of eight (8) medicinal plants in Ghana. We also assessed the effects of the extracts on superoxide dismutase enzyme (SOD) activity. The SODs are antioxidant enzymes that are necessary for life. They convert superoxide radical into hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen, thus mitigating oxidative stress. Based on their traditional uses and medicinal properties, the plants Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Lippia multiflora Moldenke, Morinda lucida Benth., Parkia clappertoniana Keay, Terminalia ivorensis A.Chev, Baphia nitida Lodd, Tabernaemontana crassa Benth. and Treculia Africana Decne. e × Trecul, were selected for the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ghanaian Medicinal Plants, Their Families, Parts Used and Voucher Specimen Numbers.

| Sample ID | Plant name | Family | Part used | Voucher specimen No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| J48 | Morinda lucida | Rubiaceae | Leaves | JJNC008L |

| J49 | Parkia clappertoniana | Leguminosae | Stem-bark, Leaves | JJNC050SBL |

| J50 | Tabernaemontana crassa | Apocynaceae | Root | JJNC067R |

| J51 | Terminalia ivorensis | Combretaceae | Stem-bark, Leaves | JJNCO48SBL |

| J52 | Baphia nitida | Fabaceae | Stem-bark | JJNC040SB |

| J53 | Lippia multiflora | Verbanaceae | Leaves | JJNC002L |

| J54 | Cinnamomum zeylanicum | Lauraceae | Stem-bark | JJNC066SB |

| J55 | Treculia africana | Moraceae | Stem-bark | JJNC033SB |

Methods

Plant Collection and Extract Preparation

The leaves of Morinda lucida and Lippia multiflora, roots of Tabernaemontana crassa, stem-bark of Baphia nitida, Cinnamomum zeylanicum and Treculia Africana, and stem-bark and leaves of Parkia clappertoniana and Terminalia ivorensis were collected from Mampong-Akuapim in the Eastern region of Ghana by staff of the Center for Plant Medicine Research, Ghana, based on anecdotal evidence on their medicinal properties. These medicinal plants are used by Ghanaian Traditional Medicine Practitioners to treat malaria and other conditions. The plants were authenticated by Mr Heron Blagogee, a Senior Botanist at the Center for Plant Medicine Research, Ghana, where Voucher specimens were deposited (Table 1). The plant parts were air-dried, pulverized and extracted with 50% ethanol at room temperature for 24 h. The extraction procedure was repeated three times and the supernatants were pooled. The ethanol content of the extracts were removed using a BUCHI® rotary evaporator. The remaining aqueous extracts were lyophilized (LABCONCO®, USA) to obtain dried extracts.

Anti-Plasmodial Assay

The chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum strain 3D7 was cultured in human red blood cells (RBCs) and RPMI 1640 culture medium. Subsequently, anti-plasmodial activity screening of the extracts was performed using the SYBR green I-based fluorescence assay described by Kwansa-Bentum et al. 14 The extract stock (50 mg/mL in 50% hydroethanol) solutions were diluted serially in a culture medium to obtain working concentrations in the range of 1 to 2000 μg/mL for the assay. Aliquots of extracts were added sorbitol synchronized parasitized RBCs (ring stage) and incubated as earlier described, at 2% hematocrit and 1% parasitaemia. Wells containing untreated parasites (with vehicle) were used as negative controls while the positive control experiment consisted of parasite infected RBCs (iRBCs) treated with chloroquine. The cultures were incubated for 72 h in a humidified chamber in an incubator at 37 °C under low oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. Afterward lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 5 mM EDTA, 0.008% saponin, 0.08% triton-X 100 and 1 × SYBR green I (10 000 × in DMSO) was added to the wells, and the contents were mixed gently and incubated in the dark at room temperature (26 °C) for 1 h. Fluorescence in each well was read using a multi-well plate reader (Tecan Infinite M200, Austria) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 497 and 530 nm, respectively. The fluorescence readings were used to calculate the percentage inhibition of parasite growth. The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of the extracts were extrapolated from plots of percentage inhibition against extract/drug concentrations. All chemicals and reagents used for the study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis MO, USA) and Gibco BRL Life Technologies (Paisley, Scotland).

Cytotoxicity Assay

The 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide-based colorimetric selective assay (MTT-Based CSA) was used to determine the cytotoxic effect of the extracts on uninfected red blood (RBCs) and human HL-60 cells as described.8,11 Briefly, 90 µL of washed RBCs at 2% hematocrit were added to 10 μL aliquots of serially diluted extract preparations (0-1250 μg/mL) in separate wells and HL-60 cells cultured in RPMI 1640 medium were also seeded at 1 × 105 cells per well into 96-well microtiter plates, mixed and incubated at 37 °C for 72 h. Positive and negative control experiments comprising chloroquine and vehicle-treated RBCs and untreated HL-60 cells respectively were set up. Wells with extracts and culture medium were also set up as color controls for extract-signal correction. After incubation for 72 h, 20 µL of 7.5 mg/mL MTT solution (in phosphate buffer saline) was added to each well and the plate was re-incubated for 2 h and 4 h, respectively for RBC and HL-60 experiments. Formazan crystals formed from MTT were dissolved by adding acidified isopropanol and incubating the plates in the dark at room temperature (26 °C) overnight. The optical densities of the wells were measured at the wavelength of 570 nm using the multi-well plate reader. Triplicate experiments were performed. Curcumin was used as a positive control. The percentage RBC survival/cell viability in treated wells was calculated and plotted against respective extract concentrations. The 50% cytotoxic concentrations (CC50) were determined by regression analysis. The selectivity indices (SI) of the extracts ie ratio CC50/IC50 values were calculated.

Determination of Total Phenolic Content

Generally, phenols have good antioxidant properties, therefore, the total phenolic content of the extracts was determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu's method with slight modifications. 13 A concentration of 1 mg/mL of each extract was prepared in distilled water. Gallic acid standard solutions were prepared by serial dilution in the concentration range 0.0156 - 1 mg/mL. A volume of 10 µL of each sample or gallic acid solution was aliquoted into the wells of a 24-well plate, in triplicates. Subsequently, 790 µL of distilled water and 50 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent were added to each of the wells, mixed and incubated at room temperature for 8 min. One hundred and fifty microliters of Na2CO3 (20% w/v) were added and the mixtures were further incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Absorbance was read at a wavelength of 750 nm. A gallic acid standard calibration curve was plotted. The total phenolic content of extracts extrapolated from the plot was expressed in gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE/100 g extract).

Superoxide Dismutase Assay

Effects of the plant extracts on superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity were evaluated as earlier described. 15 Aliquots of 20 µL (80 µg/mL) of each sample were transferred into a 96-well plate, 200 µL 75 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.2) and 30 µL pyrogallol were added to each well. Corosolic acid was used as a positive control, and negative control was 50% hydroethanolic solution. Absorbance was read at intervals of 0 and 5 min at the wavelength of 420 nm. The effect on SOD activity was expressed as percent inhibition of the rate of autooxidation of pyrogallol as determined by the change in absorbance/min.

Phytochemical Tests

Phytochemical tests for the presence of saponins, terpenoids, tannins, alkaloids and flavonoids were carried out as described16,17 (Languon et al. 2018; Shah and Hussain, 2014). Each test was carried out using 10 mg/mL of extract.

Saponins

Aliquots of 2 mL of distilled water were added to 1 mL of each extract and shaken vigorously. Observation of a stable and persistent (≥10 min) froth suggests the presence of saponins.

Terpenoids

To a volume of 500 µL extract, 200 mL of chloroform was added, followed by the gentle addition of drops of concentrated H2SO4. The formation of an interface with a reddish-brown color suggests the existence of terpenoids. Ursolic acid was used as the positive control.

Tannins

A volume of 1 mL extract was aliquoted into test tubes and brought to a boil at 100 °C. A few drops of 0.1% FeCl3 were added. A brownish-green or blue-black coloration indicates the presence of tannins. Gallic acid was used as the positive control.

Flavonoids

A few drops of dilute NaOH solution were added to 500 µL of the extract. An intense yellow color indicated the presence of flavonoids. Quercetin was used as the positive control.

Alkaloids

To test for the presence of alkaloids, 200 µL of Wagner's reagent (Iodo-potassium iodide) was added to 500 µL of the extract. The formation of a reddish-brown precipitate indicated the presence of alkaloids. Quinidine was used as the positive control.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance between the means of the data was analyzed using One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Student's t-test. A ρ-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Anti-Plasmodial Activities of Plant Extracts

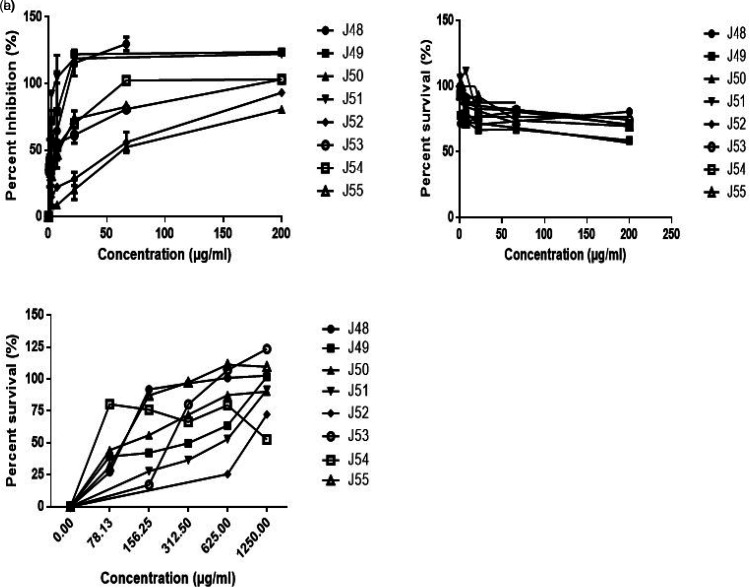

Figure 1a illustrates the dose-response curve of the inhibitory action of the medicinal plants on the Plasmodium falciparum strain 3D7. All the extracts showed concentration-dependent inhibition of the parasite growth, with a majority of them showing moderate to strong anti-plasmodial action against the parasite with IC50 values in the range of 0.96 to 6.6 µg/mL. The IC50 values were in the following increasing order: J51<J49<J53<J54<J48<J55 <J52<J50 (Table 2). The strongest anti-plasmodial activity was exhibited bythe extract of T. ivorensis (0.956 µg/mL), which was followed by P. clappertoniana (1.133 µg/mL) and L. multiflora (3.036 µg/mL) extracts. The weakest anti-plasmodial activity was shown by T. crassa extract (62.23 µg/mL). The IC50 value of positive control, chloroquine was 5.5 ng/mL. There was a significant difference between the IC50 values of the extracts and that of chloroquine (ρ < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effects of plant extracts on (a) P. falciparum strain 3D7 infected RBCs, (b) uninfected RBCs and (c) HL-60 leukemia cells. Names of the plants are shown in Table 1.

Table 2.

Anti-Plasmodial Activity Cytotoxicity and Selectivity Indices of Plant Extracts.

| IC50 (µg/mL) CC50 (µg/mL) | Selectivity index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample ID | iRBC | RBC | HL-60 | iRBC | HL-60 |

| J48 | 4.163 | >200 | 95.650 | >48.04 | 22.98 |

| J49 | 1.133 | >200 | >200 | >176.52 | >176.52 |

| J50 | 62.230 | >200 | 110.100 | >3.21 | 1.77 |

| J51 | 0.956 | >200 | >200 | >209.31 | >209.31 |

| J52 | 44.360 | >200 | >200 | >4.51 | >4.51 |

| J53 | 3.036 | >200 | >200 | >65.88 | >65.88 |

| J54 | 4.051 | >200 | nd | >49.37 | Nd |

| J55 | 6.616 | >200 | 95.520 | >30.23 | 14.44 |

| CHQ | 0.005 | 0.051 | nd | 98.04 | Nd |

SI>2 indicates good selectivity of a therapeutic agent; iRBC, represents RBCs infected with Plasmodium falciparum strain 3D7. nd: Not determined.

Cytotoxicities and Selectivity Indices of Plant Extracts

Cytotoxic effects of the extracts on RBCs are shown in the RBC survival curves (Figure 1b). All the extracts demonstrated a weak cytotoxic effect on the human RBCs at the highest extract concentration of 200 µg/mL, with percent cell survival >50%. Similarly, the tested extracts showed weak or no cytotoxic effects on the HL-60 leukemia cells (at 200 µg/mL) as shown in Figure 1c. Curcumin, used at positive control for the cytotoxicity assay gave an IC50 value of 16.76 µg/mL. Thus, generally, the extracts demonstrated weak cytotoxic action on both human cells tested (Table 2).

Selective toxicities of the extracts on the parasites compared to RBCs and HL-60 cells are shown in Table 2. Extracts J49 and J51 with the strongest anti-plasmodial action demonstrated the highest parasite SI of 176.52 and 209.31, respectively for both RBCs and HL-60 cells.

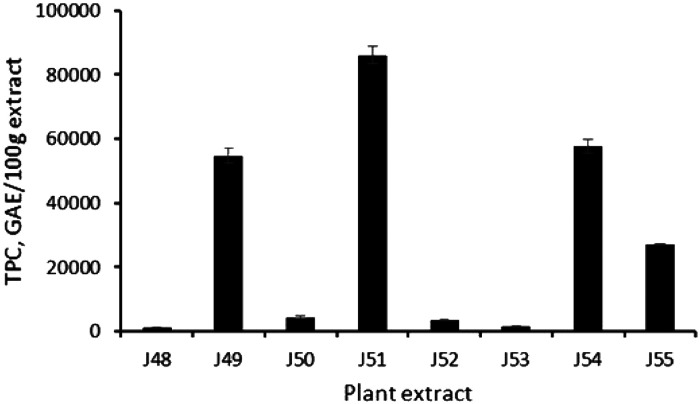

Total Phenolic Content of Extracts

The total phenolic contents of the plant extracts are shown in Figure 2. Total phenolic content of the range 1287.1 to 85 969.09 mg GAE/100 g extract were measured. Extract J51 demonstrated the highest phenolic content of 85 969.0 mg GAE/100 g extract whereas extract J48 demonstrated the lowest total phenolic content of 1287.1 mg GAE/100 g extract.

Figure 2.

Total phenolic content of plant extracts. Ten micrograms per milliliter of each plant extract were tested.

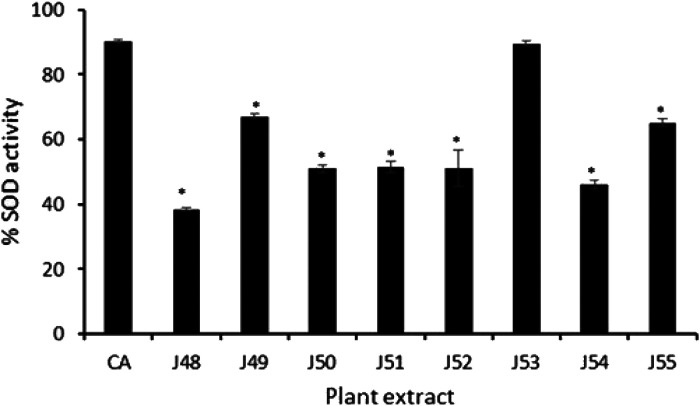

Effect of Plant Extracts on SOD Activity

Figure 3 shows the effect of the plant extracts on the activity of the antioxidant enzyme SOD. Extract J53 caused the highest increase in SOD activity which was comparable to the activity of the positive control (CA). Each of the extracts caused a ≥40% increase in enzyme activity compared to the control.

Figure 3.

Effect of plant extracts on SOD activity. Eighty micrograms per milliliter (80 µg/mL) of each plant extract was tested. CA: Corosolic acid; *, represents a significant difference between %SOD of the positive control (CA) and the plant extracts (P ≤ 0.001).

Results of Phytochemical Tests

Qualitative tests were performed to determine the presence of the phytochemicals saponins, terpenoids, tannins, flavonoids and alkaloids in the eight plant extracts. Table 3 shows the phytochemicals identified in the extracts. Extracts J49, J54 and J55 contained all the five phytochemicals above.

Table 3.

Phytochemical Constituents of Plant Extracts.

| Phytochemical | J48 | J49 | J50 | J51 | J52 | J53 | J54 | J55 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saponins | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Terpenoids | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| Tannins | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| Flavonoids | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Alkaloids | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

indicates present.

indicates absent.

Discussion

The anti-plasmodial effects of medicinal plants from Ghana have been reported in several studies.6–8 In this study, we investigated the in vitro anti-plasmodial action of hydroethanolic extracts of eight (8) plant species; Baphia nitida, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Lippia multiflora, Morinda lucida, Parkia clappertoniana, Tabernaemontana crassa, Terminalia ivorensis and Treculia Africana. We also evaluated the selective toxicity of the plants on human cells (uninfected RBCs and HL-60 cells) and their antioxidant properties. Phytochemical constituents of the extracts were also investigated.

Recent studies outline stringent endpoint criteria for biological activity and selective activity. Philippe et al. 18 described the anti-plasmodial effects of plant extracts as highly active (IC50 ≤ 5μg/mL); moderately active (5 < IC50≤15 μg/mL); weakly active (15<IC50 ≤ 50 μg/mL) and inactive (IC50 > 50 μg/mL). Anti-plasmodial activities of plant extracts have also been categorized as follows: very active (<5 μg/mL), active (5-50 μg/mL), weakly active (50-100) and inactive (100). 19 Based on both categorizations the plant species Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Lippia multiflora, Morinda lucida, Parkia clappertoniana and Terminalia ivorensis showed high activity whereas Treculia Africana showed moderate activity. According to the categorization of Philippe et al. 18 Baphia nitida is weakly active and Tabernaemontana crassa is inactive. Parkia clappertoniana and Terminalia ivorensis (each extracted from a mixture of the stem, bark and leaves) showed the strongest activities with IC50 values of 1.13 ug/mL and 0.95 μg/mL, respectively. Earlier studies have reported the anti-plasmodial activities of their parts on P. falciparum strain 3D7. The ethanolic extract of the stem bark of T. ivorensis was reported as showing an IC50 value of 6.95 μg/mL and the aqueous extracts of the leaves showed the value of 0.64 μg/mL. 9 The aqueous leaf extract of T. ivorensis however gave an IC50 value of 10.52 μg/mL in chloroquine-resistant W2 strains. 9 The aqueous extract of the leaves of Parkia biglobosa a common specie of Parkia genus has also been reported to have an IC50 value of 56.23 µg/mL while the phenolic fraction of the methanolic extract had the value of 0.51 µg/mL in P. falciparum isolates from malaria patients.20,21 Strong activities of the plant extracts in this study may be resulting from the composite activities from the various components of the extracts. Although there was no correlation between the phenolic content of the extracts and the anti-plasmodial activities, T. ivorensis and P. clappertoniana which showed the strongest anti-plasmodial activities, had the highest phenolic content. Different plant constituents may act synergistically to improve their combinatorial effect. This effect may be due to certain complex formation from the various constituents which elicits potent inhibition than their individual effects. 22

This study also reports for the first time, the in vitro anti-plasmodial activities of B. nitida, T. crassa and T. africana. T. africana showed moderate anti-plasmodial activity. Studies have reported comparable anti-diabetic effects of the hydro-acetone extract of its root bark and hemagglutination inhibition of the seeds.23,24 However, our study reports the anti-plasmodial activity of its stem-bark (IC50 value of 6.62 µg/mL).

The selective action of the plants for the malaria parasite is an important indicator for the potency selection of medicinal plants. It represents the ratio of cytotoxicity to biological activity. Some other studies have described the selective index of some medicinal plants as; low (4 ≤ SI<10), selective (10>SI≤25), and highly selective (≥25).9,25,26 P. clappertoniana and T. ivorensis showed high selectivity towards the malaria parasite. This suggests that the extracts possess components with promising anti-plasmodial activity. The low toxicity of these plant extracts to human cells is consistent with earlier studies that reported that the aqueous seed extract of P. clappertonian showed no observable maternal and developmental toxicities in Sprague-Dawley rats and ICR mice. On the other hand, the aqueous extracts of T. ivorensis demonstrated an SI≥3.48 against human umbilical vein endothelial cells, 9 and the aqueous root extract of T. africana showed no indicative toxicity to the liver, heart and muscles enzymes in vivo. 27 Fifty percent cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of C. zeylanicum in Jurkat cells was not determined due to limitation in the amount of plant extract.

Antioxidant therapy in malarial infections remains to be fully rationalized. Studies have nonetheless reported its role as a viable therapeutic strategy for alleviating plasmodium-induced oxidative stress and its associated complications. 10 The increased metabolic rate of the rapidly growing and multiplying parasites leads to the generation of large quantities of redox-active by-products, and, consequential imbalance in the oxidant-antioxidant system. The changes have been observed in children with severe malaria and they have been associated with P. vivax malaria. 28 All the plants studied showed various antioxidant potentials. Lippia multiflora leaf extract exhibited a stronger SOD inductive effect which was comparable to the positive control. The antioxidant activity recorded could partly be attributable to the high total phenolic content of the extracts. Interestingly, T. ivorensis which had the highest phenolic content exhibited the strongest anti-plasmodial activity. Their antioxidant property could be beneficial for adjunctive therapeutic application in malaria management.

The anti-plasmodial, antioxidant and cytotoxic effects of P. clappertoniana, T. ivorensis and T. africana extracts could partly be attributable to some of the identified chemical constituents of the extracts. All the five phytochemicals tested, saponins, terpenoids, tannins flavonoids and alkaloids were present in the three plant extracts except T. ivorensis in which terpenoids were not detected. These findings are corroborated by earlier reports that revealed the presence of alkaloids, anthraquinones, flavonoids, glycosides, saponins, steroids, tannins and triterpenoids in P. clappertoniana; alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, saponins, tannins, and terpenes in T. ivorensis and anthraquinone, cardiac glycosides, flavonoids, polyphenols and saponins in T. africana.29–32 Further studies have elucidated ivorenosides A, B and C as triterpene saponins in T. ivorensis and, 6,9-dihydro-megastigmane-3-one, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, α-pinene, myrtenal, limonene, camphene and n-hexanoic acid in T. Africana.33,34 These natural product constituents could be investigated further for their anti-plasmodial effects.

Conclusion

This study has indicated a strong anti-plasmodial action and high selectivity of Terminalia ivorensis, Parkia clappertoniana and Lippia multiflora extracts. We also report for the first time anti-plasmodial action of Baphia nitida, Tabernaemontana crassa and Treculia Africana. The strong anti-plasmodial activity of Terminalia ivorensis could partly be due to its high phenolic content and the other phytochemical constituents. Further studies are warranted to isolate and characterize the active principles in the bioactive plant extracts.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the staff of CPMR, Mampong-Akwapim and Departments of Clinical Pathology and Parasitology, Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana, particularly Ms. Abigail Aning for their technical support.

Author Contributions: RAO and AKN conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination. KA, PA, KB-AO and ED carried out the experimental studies and data analysis. MMS, RA, FA and AAA worked on the plant samples. KA drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data Availability: Data on this research will be made available on request.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana (NMIMR-IRB CPN 001/12-13 Revd 2017). Informed consent was sought from volunteers who donated blood samples that were used to culture the malaria parasite.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana and Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS), Japan

ORCID iDs: Regina Appiah-Opong https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4219-7107

Frederick Ayertey https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1691-5646

References

- 1.WHO, The World malaria report 2019. Accessed February 2, 2021. www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/world-malaria-report-2019; 2019.

- 2.Diakité SAS, Traoré K, Sanogo I, et al. A comprehensive analysis of drug resistance molecular markers and Plasmodium falciparum genetic diversity in two malaria endemic sites in Mali. Malar J. 2019;18:361. 10.1186/s12936-019-2986-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO, Drug resistance in malaria. WHO/CDS/CSR/DRS/2001.4. Accessed February 2. www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/drugresist/malaria.pdf; 2001.

- 4.Ocan M, Akena D, Nsobya S, et al. Persistence of chloroquine resistance alleles in malaria endemic countries: a systematic review of burden and risk factors. Malar J. 2019;18:76. 10.1186/s12936-019-2716-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliveira AB, Dolabela MF, Braga FC, Rose LRPJ, Varotti FP, Póvoa MM. Plant-derived antimalarial agents: new leads and efficient phytomedicines. Part I. Alkaloids. An Acad Bras Ciênc. 2009;81(4):715-740. https://www.scielo.br/j/aabc/a/WbPqdfJChZtZfKnBg5QJKFy/?format=pdf&lang=en [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imoro AZ, Khan AT, Deo-Anyi EJ. Exploitation and use of medicinal plants, northern region. Acad J. 2013;7(27):1984-1993. 10.5897/JMPR12.489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asase A, Oteng-Yeboah AA, Odamtten GT, Simmonds MS. Ethnobotanical study of some Ghanaian anti-malarial plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99(2):273-279. http://doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appiah-Opong R, Nyarko AK, Dodoo D, Gyang FN, Koram KA, Ayisi NK. Antiplasmodial activity of extracts of Tridax procumbens and Phyllanthus amarus in in vitro Plasmodium falciparum culture system. Ghana Med J. 2011;45(4):143-150. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3283098/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komlaga G, Cojean S, Dickson RA, et al. Antiplasmodial activity of selected medicinal plants used to treat malaria in Ghana. Parasitol Res. 2016;115(8):3185-3195. http://doi:10.1007/s00436-016-5080-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isah MB, Ibrahim MA. The role of antioxidants treatment on the pathogenesis of malarial infections: a review. Parasitol Res. 2014;113(3):801-809. http://doi:10.1007/s00436-014-3804-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appiah-Opong R, Asante IK, Osei Safo D, et al. Cytotoxic effects of Albizia zygia (DC) J.F. Macbr, a Ghanaian medicinal plant against T-lymphoblast-like leukemia, prostate and breast cancer cell lines. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;8(5):392-396. https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps/article/view/10656 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acheampong F, Larbie C, Appiah-Opong R, Arthur F, Tuffour I. In vitro antioxidant and anticancer properties of hydroethanolic extracts and fractions of Ageratum conyzoides. Eur J Med Plants. 2015;7(4):205-214. http://doi:10.9734/EJMP/2015/17088 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anim MT, Larbie C, Appiah-Opong C, Tuffour I, Owusu KB-O, Aning A. Extracts of Codiaeum variegatum (L.) A. Juss is cytotoxic on human leukemic. Breast and prostate cancer cell lines. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2016;6(11):087-093. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwansa-Bentum B, Agyeman K, Larbi-Akor J, Anyigba C, Appiah-Opong R. In vitro assessment of antiplasmodial activity and cytotoxicity of Polyalthia longifolia leaf extracts on Plasmodium falciparum strain NF54. Mal Res Treat. 2019. 10.1155/2019/6976298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alam MN, Bristi NJ, Rafiquzzaman M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods of evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharm J. 2013;21(2):143-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah MD, Hossain MA. Total flavonoids content and biochemical screening of the leaves of tropical endemic medicinal plant merremia borneensis. Arab J Chem. 2014;7(6):1034-1038. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Languon S, Tuffour I, Quayson EE, Appiah-Opong R, Quaye O. In vitro evaluation of cytotoxic activities of marketed herbal products in Ghana. J Evid-Based Integr Med. 2018; 23:2515690X18790723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philippe G, Angenot L, De Mol P, et al. In vitro screening of some strychnos species for antiplasmodial activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97(3):535-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumari SD, Satish PV, Somaiah K, Rekha SN, Brahmam P, Sunita K. Antimalarial activity of Polyalthia longifolia (false ashoka) against chloroquine sensitive Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 strain. World J Pharm Sci. 2016;4(6):495-501. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Builders M, Wannang N, Aguiyi J. Antiplasmodial activities of Parkia biglobosa leaves: in vivo and in vitro studies. Ann Biol Res. 2011;2(4):8-20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Builders M, Alemika T, Aguiyi J. Antimalarial activity and isolation of phenolic compound from Parkia biglobosa. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci. 2014;9(3):78-85. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamdy AS, Mohamed BMA, El-Sideek El-Sideek L, May M. Study on the antimicrobial activity and synergistic/antagonistic effect of interactions between antibiotics and some spice essential oils against pathogenic and food-spoiler microorganisms. Am J Appl Sci Res. 2013;9(8):5076-5085. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oyelola OO, Moody JO, Odeniyi MA, Fakeye TO. Hypoglycemic effect of Treculia africana decne root bark in normal and alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2007;4(4):387-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimokawa M, Nsimba-Lubaki SM, Hayashi N, et al. Two jacalin-related lectins from seeds of the african breadfruit (treculia africana L.). Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2014;78(12):2036-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soh PN, Benoit-Vical F. Are west african plants a source of future antimalarial drugs? J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114(2):130-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weniger B, Robledo S, Arango GJ, et al. Antiprotozoal activities of Colombian plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;78(2–3):193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omage K, Onoagbe OI, Erifeta OG. Effects of aqueous root extract of Treculia africana on glucose, serum enzymes and body weight of normal rabbits. Br J Pharm Toxicol. 2011;2(4):159-162. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narsaria N, Mohanty C, Das BK, Mishra SP, Praosad R. Oxidative stress in children with severe malaria. J Trop Pediatr. 2012;58(2):147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saleh MSM, Jalil J, Zainalabidin S, Asmadi AY, Mustafa NH, Kamisah Y. Genus parkia: phytochemical, medicinal uses, and pharmacological properties. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2):618. 10.3390/ijms22020618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnny II, Ekong NJ, Okon JE. Phytochemical screening and anti-hyperglycaemic activity of ethanolic extract of Terminalia ivorensis A. Chev. Leaves on albino wistar rats. Global Adv Res J Med Med Sci. 2014;3(8):186-189. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osabor VN, Ogar DA, Okafor PC, Egbung GE. Profile of the african bread fruit (Treculia africana). Pakistan J Nutr. 2009;8(7):1005-1008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ponou BK, Teponno RB, Ricciutelli M, et al. Dimeric antioxidant and cytotoxic triterpenoid saponins from Terminalia ivorensis A. Chev. Phytochem. 2010;71(17–18):2108-2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metuno R, Ngandeu F, Tchinda AT, et al. Chemical constituents of Treculia acuminata and Treculia africana (moraceae). Biochem Syst Ecol. 2008;36(2):148-152. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aboaba SA, Ekundayo O, Omikorede O. Constituents of breadfruit tree (Treculia africana) leaves, stem and root barks. J Essent Oil-bear Plants. 2007;10(3):189-193. [Google Scholar]