Abstract

A novel binary typing (BT) procedure, based on reversed hybridization of digoxigenin-universal linkage system-labeled bacterial DNA to strip-immobilized probes, is presented. Chromogenic detection of hybrids was performed. Staphylococcus aureus isolates (n = 20) were analyzed to establish the feasibility of BT. A technically simple and fast procedure has been developed for application in routine microbiology laboratories.

Reliable probe-based microbial typing systems are not yet commonplace in microbiological practice (1, 4, 7, 8, 12). In the past we identified domains that are differentially present within the staphylococcal genome on the basis of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. These probes were used to develop a DNA probe-based typing approach. The strain-specific DNA probes provide a simple binary output and have been presented before (13–15). We describe here the development of a new format for the binary typing technique. In the newly described procedure DNA is extracted from overnight Staphylococcus aureus cultures, labeled with the digoxigenin (DIG)-universal linkage system (ULS) (9), and reversibly hybridized to strips containing the immobilized probes. Signal is generated by chromogenic staining, and binary types can be read visually. This novel binary typing system will be introduced, and its versatility will be discussed.

Well-characterized strains of S. aureus (n = 20) were obtained from a reference collection (10). Isolates were cultured onto blood agar plates at least once, and single colonies were used for further testing.

DNA was isolated (i) by the protocol described by Boom et al. (3), (ii) with a miniprep of bacterial genomic DNA with a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide-NaCl solution (2), (iii) by extraction with phenol-chloroform (5), and (iv) by proteinase K-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-treatment and boiling. Another method (method v) consisted of simple DNA isolation by 10 min of boiling only. An alkaline method (method vi) for DNA extraction was used as well. Finally, a method (method vii) used the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit. The extraction of staphylococcal DNA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA size distribution and the concentrations of all preparations were estimated by gel electrophoresis and were compared to those of a reference series of bacteriophage λ DNA (5). DNA was stored at −20°C for labeling and hybridization experiments.

For the optimization of DNA labeling, purified S. aureus DNA was labeled by using three different ratios (micrograms of DNA versus units of ULS), namely, 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 (digoxigenin-ULYSIS nucleotide labeling kit; KREATECH Diagnostics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). A serial dilution of labeled DNA from all strains (1 μl) was spotted onto a membrane to check the labeling efficiency. The procedures for the generation, validation, and application of the 12 strain-specific DNA probes have been described in detail elsewhere (13–15). Purified DNA probes (n = 12) were spotted (1 μl) onto a membrane strip (5 by 80 mm; Hybond N+; Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). For hybridization quality control, 10 ng of petunia DNA (LMC 1322) and 0.25 ng of the S. aureus amplified nuc gene (6) were spotted as negative and positive hybridization controls, respectively. The DNA probes were denatured by 0.5 M NaOH–1.5 M NaCl treatment for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the strips were neutralized with 0.5 M Tris-HCl–1.5 M NaCl (pH 7.4) for 15 min at room temperature (RT). The strips were washed with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate (5), and the denatured DNA was cross-linked on the strip with UV light (280 nm). Each strip was transferred into a Greiner tube (15 ml), and 1 ml of DIG Easy Hyb buffer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Almere, The Netherlands) was added. The labeled DNA was denatured for 5 min at 100°C and quenched on ice. The sample was centrifuged to collect condensate, and 1 ml of DIG Easy Hyb buffer was added. The labeled DNA was then added to the hybridization mixture, and the mixture was incubated overnight at 42°C in a rotation oven. After hybridization, the strips were washed twice in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS for 5 min each time at RT and twice in 0.5× SSC–0.1% SDS for 15 min each time at 68°C. The strips were processed by the protocol accompanying the Roche Molecular Biochemicals hybridization kit. After posthybridization wash steps, the strips were equilibrated in 1× maleic buffer for 1 min. The strips were blocked for 30 to 60 min at RT with 1× blocking buffer under slight agitation. The strips were incubated with conjugate (anti-DIG alkaline phosphatase conjugate, 150 mU/ml) for 10 min at RT. The strips were washed twice for 15 min each time in 1× wash buffer at RT and were equilibrated twice for 5 min each time in detection buffer. Finally, the strips were incubated in freshly prepared color substrate (nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate ready-to-use tablets; Roche Molecular Biochemicals) for a maximum of 3 h at RT in the dark. Hybridization of labeled genomic DNA with each of the 12 different DNA probes (probes AW-1 through AW-12) was scored with a 1 or a 0 according to the presence or absence of the hybridization signal, respectively. The combination of hybridization results forms the binary type.

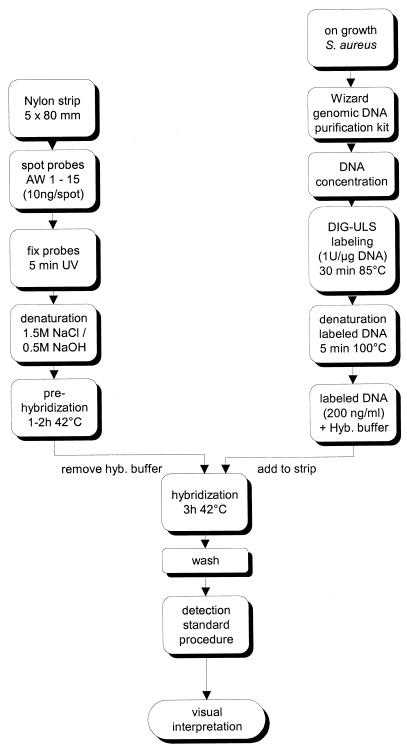

The current conditions for the binary typing procedure are summarized below and are outlined in Fig. 1. Genomic staphylococcal DNA was purified with the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit and labeled with DIG-ULS (target DNA versus label at a ratio of 1:1). A concentration of 200 ng of labeled DNA per ml of hybridization buffer was used.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram showing the novel binary typing protocol. hyb., hybridization.

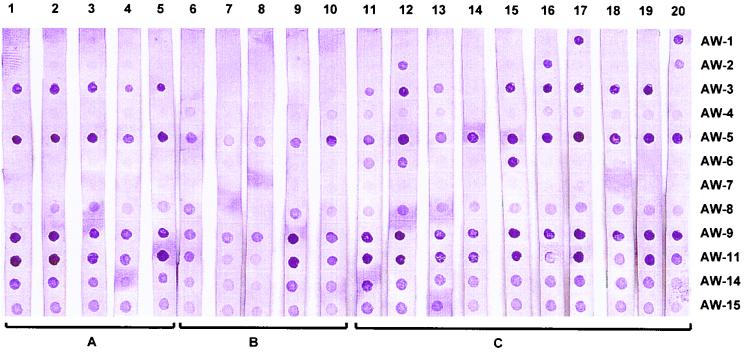

The hybridization results for the S. aureus strain collection, determined by the currently developed reversed hybridization procedure, are depicted in Fig. 2 and are specified in Table 1. Strains 1 to 5 (Fig. 2, lanes 1 to 5, respectively) showed identical binary codes. Strains 6 to 10 (Fig. 2, lanes 6 to 10, respectively), representing genetically related strains, displayed binary patterns that varied for no more than 2 of the 12 probes. Of the 10 unique strains (Fig. 2, lanes 11 to 20, respectively), all except strains 18 and 19 exhibited unique binary codes.

FIG. 2.

Binary typing results for the methicillin-resistant S. aureus strain collection obtained after hybridization on the strip-immobilized DNA probe panel (probes AW-1 through AW-15).

TABLE 1.

Comparative analysis of characteristics obtained by the binary typing technique and other genotyping methods for the panel of methicillin-resistant S. aureus strainsa

| MRSA strain no. | Binary code | PFGE type | TAR916 SHIDA type | AP PCR type by:

|

Phage type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAPD with ERIC2 | RAPD with AP1 | RAPD with AP7 | |||||

| Witte 1 | 001010011111 | A | A | A | A | A | 77 |

| Witte 2 | 001010011111 | A | A | A | A | A | 77 |

| Witte 3 | 001010011111 | A | A | A | A | A | 77 |

| Witte 4 | 001010011111 | A | A | A | A | A | 77 |

| Witte 5 | 001010011111 | A | A | A | A | A | 77 |

| Witte 6 | 000110011111 | B | B | B | B | B | NT |

| Witte 7 | 000010001111 | B1 | B | B | B | B | 95 |

| Witte 8 | 000010001111 | B2 | B | B | B | B | 80 |

| Witte 9 | 000010011111 | B3 | B | B | B | B | 80 |

| Witte 10 | 000110011111 | B4 | B | B | B | B | NT |

| Witte 11 | 001111011111 | C | A | C | A | A | 75, 77, 84, 84a, 994 |

| Witte 12 | 011111011111 | D | C | D | C | C | 6, 81 |

| Witte 13 | 001110011111 | E | D | E | A | D | 6, 47, 77, 83A, 85, 994 |

| Witte 14 | 000010011111 | F | E | F | D | E | 85 |

| Witte 15 | 001011011111 | G | F | E′ | C | F | 85 |

| Witte 16 | 011110011111 | H | G | G | A | D | 6, 47, 66 |

| Witte 17 | 101110011111 | I | H | H | A | E | 75, 77 |

| Witte 18 | 000110011111 | J | A | H | A | A | 47, 54, 75, 77, 84, 85, 812 |

| Witte 19 | 000110011111 | K | I | I | B | G | 29, 52, 77 |

| Witte 20 | 110110011111 | L | J | F | A | I | 29 |

Data are from reference 10. Abbreviations: MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; TAR916 SHIDA, Transposon 916, Shine Dalgarno; AP PCR, arbitarily primed PCR; RAPD, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis (ERIC2, AP1, and AP2 are primers); NT, not typeable.

Here we present a new format of binary typing as an example of a single-species typing test developed for the characterization of S. aureus strains. In previous studies, we defined the resolution, reproducibility, and stability of the epidemiological markers of the binary typing technique (11, 13–15). Technically speaking, the initial method, which involves repeated hybridization of the probe to digested staphylococcal DNA, was complex and time-consuming. We therefore developed a simple and fast format for the characterization of S. aureus strains based on reversed hybridization with 12 strip-immobilized DNA probes. The major advantage of ULS labeling for this application is the direct labeling of culture-amplified total genomic S. aureus DNA (target labeling). The additional value of binary typing is its simplicity, speed, reproducibility, and lack of need for expensive peripheral equipment. The efficiency of the labeling reaction with DIG-ULS (9) depends on the time, the temperature, the label-to-DNA ratio, and the purity of the DNA. A simple and standardized procedure resulted in optimal labeling and hybridization results. Hybridization conditions and probe and target concentrations were optimized.

The data obtained by the novel binary typing protocol are identical to those that were obtained by the coventional binary typing method. Epidemiologically linked strains were again identified as clusters, whereas unique isolates were well differentiated. The reversed hybridization data are corroborated by those obtained by other typing techniques such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis (Table 1).

The new binary typing protocol described here provides a simple and fast probe-based molecular typing strategy for the characterization of S. aureus strains and generates easily interpretable results, which can be compiled in a database. This culture-amplified nucleic acid probe technology can be developed for the characterization of other species and can be easily expanded with probes that directly detect genes associated with virulence factors and resistance determinants. It may be concluded that this technique comprises a compact, user-friendly S. aureus typing system suitable for use in the development of an international database for both methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains. In addition, the binary typing system has the clear potential to be useful in peripheral laboratories as well. The interlaboratory reproducibility of the assay is currently the subject of a multicenter study.

Acknowledgments

Sharmila Naidoo is acknowledged for critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was partially funded by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs (project BTS 97134).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allerberger F, Fritschel S J. Use of automated ribotyping of Austrian Listeria monocytogenes isolates to support epidemiological typing. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;35:237–244. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. In: Ausubel R B F M, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1994. pp. 2.4.1–2.4.2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boom R, Sol C J, Salimans M M, Jansen C L, Wertheim-van Dillen P M, van der Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A, van Agterveld M, van Soolingen D, Kuijper S, Bunschoten A, Molhuizen H, Shaw R, Goyal M, van Embden J. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:907–914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.907-914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sambrook J E, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shortle D. A genetic system for analysis of staphylococcal nuclease. Gene. 1983;22:181–189. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spratt B G. Multilocus sequence typing: molecular typing of bacterial pathogens in an era of rapid DNA sequencing and the internet. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:312–316. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80054-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Belkum A, Kluytmans J, van Leeuwen W, Bax R, Quint W, Peters E, Fluit A, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C, van den Brule A, Koeleman H, Melchers W, Meis J, Elaichouni A, Vaneechoute M, Moonens F, Maes N, Struelens M, Tenover F, Verbrugh H. Multicenter evaluation of arbitrarily primed PCR for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1537–1547. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1537-1547.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Belkum A, Linkels E, Jelsma T, van den Berg F M, Quint W. Non-isotopic labeling of DNA by newly developed hapten-containing platinum compounds. BioTechniques. 1994;16:148–153. . (Erratum, 18:636, 1995.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Belkum A, van Leeuwen W, Kaufmann M E, Cookson B, Forey F, Etienne J, Goering R, Tenover F, Steward C, O'Brien F, Grubb W, Tassios P, Legakis N, Morvan A, El Solh N, de Ryck R, Struelens M, Salmenlinna S, Vuopio-Varkila J, Kooistra M, Talens A, Witte W, Verbrugh H. Assessment of resolution and intercenter reproducibility of results of genotyping Staphylococcus aureus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of SmaI macrorestriction fragments: a multicenter study. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1653–1659. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1653-1659.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Belkum A, van Leeuwen W, Verkooyen R, Sacilik S C, Cokmus C, Verbrugh H. Dissemination of a single clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among Turkish hospitals. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:978–981. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.978-981.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Zee A, Verbakel H, van Zon J C, Frenay I, van Belkum A, Peeters M, Buiting A, Bergmans A. Molecular genotyping of Staphylococcus aureus strains: comparison of repetitive element sequence-based PCR with various typing methods and isolation of a novel epidemicity marker. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:342–349. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.342-349.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Leeuwen W, Sijmons M, Sluijs J, Verbrugh H, van Belkum A. On the nature and use of randomly amplified DNA from Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2770–2777. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2770-2777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Kreiswirth B, Verbrugh H. Genetic diversification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a function of prolonged geographic dissemination and as measured by binary typing and other genotyping methods. Res Microbiol. 1998;149:497–507. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(98)80004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Leeuwen W, Verbrugh H, van der Velden J, van Leeuwen N, Heck M, van Belkum A. Validation of binary typing for Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:664–674. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.664-674.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]