Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the primary risk factor for cervical cancer. While the HPV vaccine significantly reduces the risk of HPV infection and subsequent cervical cancer diagnosis, underuse is linked to lack of knowledge of its effectiveness in preventing cervical cancer. The purpose of this study was to evaluate a cancer educational intervention (titled “MOVENUP”) to improve knowledge of cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine among predominantly African American communities in South Carolina. The MOVENUP cancer educational intervention was conducted among participants residing in nine South Carolina counties who were recruited by community partners. The 4.5-h MOVENUP cancer educational intervention included a 30-min module on cervical cancer, HPV, and HPV vaccination. A six-item investigator-developed instrument was used to evaluate pre- and post-intervention changes in knowledge related to these content areas. Ninety-three percent of the 276 participants were African American. Most participants reporting age and gender were 50+ years (73%) and female (91%). Nearly half of participants (46%) reported an annual household income <$40,000 and 49% had not graduated from college. Statistically significant changes were observed at post-test for four of six items on the knowledge scale (P < 0.05), as compared to pre-test scores. For the two items on the scale in which statistically significant changes were not observed, this was due primarily due to a baseline ceiling effect.

1. Introduction

1.1. Cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates in the United States (US) and in South Carolina

The American Cancer Society notes that 13,170 new cases of invasive cervical cancer were diagnosed in 2019 in the United States, and approximately 4250 women died from cervical cancer (American Cancer Society, 2019). Nationally, the cervical cancer age-adjusted incidence rate from 2008 to 2012 for NHB women was 10.0 per 100,000 reflecting an absolute difference of 2.9 and a rate ratio of 1.41 compared to Non-Hispanic white (NHW) women (American Cancer Society, 2016). African American and Latina women had the highest cervical cancer age-adjusted incidence rates (8.7 and 9.3 new cases per 100,000 persons, respectively) per year in 2012–2016 compared to white women (7.2 new cases per 100,000 persons) (National Cancer Institute, 2019). During this period, African American and Latina women also had a higher cervical cancer age-adjusted mortality rate (3.5 and 2.6 deaths per 100,000 persons, respectively) per year compared to white women (2.2 deaths per 100,000 persons) (National Cancer Institute, 2019).

According to the most recent state-level data for South Carolina from 2009 to 2017, the age-adjusted cervical cancer mortality rate for NHW women was 2.2 per 100,000 and for African American women was 3.9 per 100,000, for a total of 645 deaths during this time period (South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. Public Health Statistics and Information Services: Division of Biostatistics and Health GIS, 2019b). From 2009 to 2016, the age-adjusted cervical cancer incidence rate for NHW women was lower (7.7 per 100,000) compared to African American women (9.3 per 100,000) (South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. Public Health Statistics and Information Services: Division of Biostatistics and Health GIS, 2019a).

Evidence suggests there are racial and geographic factors which may contribute to the cancer disease burden with higher risk of mortality for underserved, rural women in the southern region of the United States (Moore et al., 2018). African American women and men in South Carolina also experience cancer health disparities for many preventable cancer types (South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. Public Health Statistics and Information Services: Division of Biostatistics and Health GIS, 2019b).

Cervical cancer health disparities have been partially explained by the lack of early detection due to non-adherence to regular screening, and irregular or delayed follow-up after a positive screening test (Musselwhite et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2013). These differences in access to healthcare providers are usually experienced disproportionately by disenfranchised low-income and uninsured individuals. Further, cervical cancer is often described as a disease of poverty (Tsu & Ginsburg, 2017), given that it is almost entirely preventable if patients receive regular cervical cancer screening.

1.2. The importance of the HPV vaccine in preventing cervical Cancer

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a viral infection, with over 100 different subtypes. Each year, about 14 million people in the United States, including teenagers, are newly infected with HPV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). HPV is most frequently transmitted through skin to skin contact via vaginal, anal, or oral sex. In total, approximately 79 million individuals in the United States are currently living with an HPV infection, most of whom are asymptomatic and do not experience negative health effects (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Therefore, HPV infection is fairly common, and most infections are resolved by the immune system without a person even knowing they were infected.

The progression of persistent HPV infection is the leading known contributor to cervical cancer. However, with proper screening and vaccination, 93% of cervical cancers could be prevented (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). The HPV vaccine is recommended for males and females at ages 11–12, along with catch-up vaccination for those up to age 26 who missed vaccination at ages 11–12. The HPV vaccine is also approved by the United States. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for administration as early as age 9 and up through the age of 45 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Vaccination at ages 11–12 is optimal because younger adolescents have a strong immune response and the HPV vaccine is most effective prior to HPV exposure (Noronha, Markowitz, & Dunne, 2014).

HPV vaccines can provide protection for most cancer-causing HPV strains and prevent cervical cancer. The original 4-valent HPV vaccine was made from recombinant viral DNA of the L1 capsid protein encompassing strains 6, 11, 16, and 18 of the HPV. The 9-valent HPV vaccine, which is the vaccine used today, is similar but adds coverage to strains 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 (Lopalco, 2017). HPV strains 16 and 18 are responsible for >80% of cervical cancer diagnoses in the United States; therefore, the HPV vaccine is highly effective in preventing cervical cancer (Lazcano-Ponce et al., 2019). A long-term, 10-year follow-up study of the 4-valent vaccine reported that no cases of HPV types 6, 11, 16, or 18-related diseases were identified (Ferris et al., 2017).

1.3. Disparities in HPV vaccination rates

According to the National Immunization Survey for Teens (NIS-Teen) data, the percentage of 13- to 17-year-old girls who initiated and completed HPV vaccination in 2018 was 69.9% and 53.7%, respectively (Walker et al., 2019). The percentage of 13- to 17-year-old-boys who initiated and completed HPV vaccination was lower at 66.3% and 48.7%, respectively (Walker et al., 2017). In terms of HPV vaccine series completion in the United States by race and ethnicity, the NIS-Teen data showed that HPV vaccine completion rates range from 47.8% for NHW adolescents to 53.3% for African American adolescents to 56.6% for Hispanic adolescents (Walker et al., 2017).

State level rates for HPV vaccine completion range from a low of 32.6% in Oklahoma to a high of 78.1% in Rhode Island. South Carolina has observed a 4.3% 5-year annual average increase in HPV vaccination coverage, and the HPV vaccine completion rate was 41.2% in 2018. This is below the regional average of 46.7% and the national average of 51.1% (Walker et al., 2019). South Carolina, and other states in the South, remain far behind HPV vaccination rates compared to states in the Northeast and the Pacific Coast.

Past studies have shown that there is a need to improve parent, patient, and provider education on HPV vaccination; reduce vaccine costs; and improve the quality of age-appropriate (11–12 years old) provider recommendations (Gilkey et al., 2016; Lake, Kasting, Christy, & Vadaparampil, 2019). Particularly important for African American patients may be the level of trust in healthcare provider advice. One study reported African American parents who had higher trust in healthcare providers were twice as likely to follow through with HPV vaccine for their children (Fu, Zimet, Latkin, & Joseph, 2017).

1.4. Impact of the lack of knowledge of cervical cancer and/or HPV infection on HPV vaccination uptake

Given the suboptimal rates of HPV vaccination completion and low levels of knowledge of cervical cancer in underserved communities in South Carolina, the investigators of the present study implemented a cancer educational intervention aimed at assessing improvement in knowledge related to cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine among intervention participants living in predominantly African American communities. Below we describe the design, methods, and results of the cancer educational intervention to improve knowledge of cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine in nine predominantly African American communities in South Carolina.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

A pre-test/post-test design was used to evaluate knowledge changes as a result of the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention. Results related to cancer knowledge outcomes are reported elsewhere and demonstrated that general cancer knowledge and prostate cancer knowledge scores increased significantly after the cancer educational intervention (Ford et al., 2011). Whereas the focus of our prior work reported changes in cancer knowledge, the focus of the current study is to compare pre- and post-intervention changes in knowledge related to cervical cancer, HPV, and HPV vaccination.

2.2. IRB approval

The MOVENUP cancer educational intervention study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Medical University of South Carolina. Inclusion criteria included:

Residence in the communities near the location of the intervention site.

Self-identified gender.

Self-identified race and ethnicity.

Ages 21 years or older.

The pre- and post-test intervention surveys were completed by each participant and linked by an identifier that was not connected to his/her name, date of birth, or any other personal identifiers. Therefore, the investigators had no way of connecting survey responses to individual participants in the sessions, so changes in knowledge were evaluated at the group level rather than by individual participants.

2.3. Participant identification and recruitment

The study included participants from communities with large racial disparities in cancer mortality rates (Table 1). Community leaders (Champions) in each county were charged with recruiting participants to each MOVENUP session. While most of the recruited participants were African American, community members from all racial/ethnic groups were eligible to participate.

Table 1.

Age-adjusted cancer mortality rates per 100,000 population for the South Carolina (SC) countries where the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention was conducted, 2017.

| County | Non-Hispanic white | African American/black |

|---|---|---|

| Beaufort | 121.7 | 178.2 |

| Charleston | 147.1 | 189.1 |

| Clarendon | 128.8 | 191.8 |

| Colleton | 180.8 | 199.1 |

| Greenville | 145.7 | 159.8 |

| Orangeburg | 168.1 | 181.5 |

| Pickens | 161.6 | 248.3 |

| Sumter | 160.3 | 207.4 |

| York | 158.3 | 155.9 |

| All Counties in SCa | 156.8 | 186.1 |

| United Statesb | 165.4 | 190.6 |

Age-adjusted statewide and county rates for South Carolina use the 2000 US Standard population (South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. Public Health Statistics and Information Services: Division of Biostatistics and Health GIS, 2019b).

United States rates are from 2011 to 2016 (Siegel, Miller, & Jemal, 2019).

2.4. MOVENUP cancer educational intervention

The 4.5-h cancer educational intervention (including the cervical cancer and HPV educational module) is called MOVENUP and was delivered in its entirety to participants at each of the 15 study sites between February 2015 and June 2019 (one session per site). The structure and content of the 4.5-h MOVENUP cancer educational intervention were identical across all study sites and with each group of participants. The MOVENUP cancer educational intervention is unique in South Carolina for its focus on African American, rural, and medically underserved communities experiencing cancer health disparities.

The 4.5-h evidence-based MOVENUP cancer educational intervention includes a 3-h module focused on general cancer prevention and control information, a 30-min module describing prostate cancer, a 30-min module discussing the importance of cancer clinical trial participation, and a 30-min module focused on cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine.

The general cancer knowledge module of the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention was developed by the South Carolina Cancer Alliance, an 800-member, statewide, nonprofit organization with membership from the lay community, cancer survivorship support groups, healthcare organizations, public health associations, and academia. This component highlighted cancer prevention and control information (e.g., lifestyle interventions, cancer screening, early detection, diagnosis, and treatment options). The other modules of the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention were developed by the investigators. All four modules were developed for community audiences with no expert knowledge about cancer.

The MOVENUP cancer educational intervention was designed to be highly interactive and “hands on” rather than merely didactic. Participants engaged in role play as they practiced sharing the information they learned with others. They also participated in small group activities to review the information that was presented.

The MOVENUP cancer educational intervention employed a train-the-trainer approach in which each participant received a binder that included copies of the materials that were presented during the 4.5-h training session. The binder materials included the most up-to-date, evidence-based information related to cancer screening, early detection, and treatment as well as cervical cancer and HPV vaccine information. The binders also included overhead transparencies, flash drives, and CDs, which allowed the trained facilitators to make use of the different methods to disseminate the information. Additionally, the binders included talking points for each slide. The trained facilitators were encouraged to simply read the materials when they made presentations in their own communities and not add any extra information, to maintain the fidelity of the information and materials.

At the end of each MOVENUP cancer educational intervention session, each trained facilitator signed an agreement to conduct at least two MOVENUP cancer educational intervention training sessions in the next year. The MOVENUP investigators informed the trained facilitators that the future sessions could take place in venues ranging from large group meetings with their religious, civic, and social organizations to small group meetings held in someone’s home.

2.5. Rationale for the selected MOVENUP cancer educational intervention counties and demographic characteristics of the selected counties

The MOVENUP cancer educational intervention was conducted at 15 sites in nine different counties representing several different geographic regions of South Carolina (Table 1). These nine counties were: Beaufort, Clarendon, Colleton, Charleston, Greenville, Orangeburg, Pickens, Sumter, and York counties. The study included a sample of participants in counties with high racial disparities in cancer mortality rates as shown in Table 1. Residents of neighboring counties were also invited to participate. The sociodemographic characteristics of the counties in which the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention was conducted are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the South Carolina counties receiving the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention.

| County name | Population estimatesa | White | Black/AA | Amer. Indian | Asian | Native Haw. or Pacific Isl.b | Two or more races | Hisp./Latino | Median HH incomec | Per capita income | Population below the Pov. level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | USD | USD | % | |

| United States (Reference) | 327,167,434 | 76.5 | 13.4 | 1.3 | 5.9 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 18.3 | 57,652 | 31,177 | 12.3 |

| South Carolina (Reference) | 5,084,127 | 68.5 | 27.1 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 48,781 | 26,645 | 15.4 |

| Beaufort | 188,715 | 77.9 | 18.2 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 11.2 | 60,603 | 34,966 | 10.7 |

| Charleston | 405,905 | 69.2 | 26.8 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 5.1 | 57,822 | 35,587 | 13.3 |

| Clarendon | 33,700 | 50.2 | 47.5 | 0.4 | 0.8 | – | 1.0 | 3.2 | 35,838 | 20,616 | 23.2 |

| Colleton | 37,660 | 59.6 | 37.2 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 34,996 | 21,059 | 22.4 |

| Greenville | 514,213 | 76.4 | 18.5 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 9.3 | 53,739 | 29,123 | 12.4 |

| Orangeburg | 86,934 | 34.7 | 62.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | – | 1.4 | 2.4 | 34,943 | 19,489 | 24.4 |

| Pickens | 124,937 | 88.9 | 7.0 | 0.3 | 2.1 | – | 1.8 | 3.8 | 45,332 | 23,501 | 15.3 |

| Sumter | 106,512 | 47.9 | 47.9 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 4.1 | 41,946 | 21,733 | 19.1 |

| York | 274,118 | 75.0 | 19.4 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 5.7 | 59,394 | 30,387 | 11.2 |

Note: Population estimates, July 2018.

Missing data for some of these values due to small sample size.

Median Household Income/Per Capita income (in 2017 USD), 2013–2017.

Abbreviations: AA, African American; Amer., American; Haw., Hawaiian; Isl., Islander; Hisp., Hispanic; HH, household; Pov., Poverty; USD, United States Dollars.

Source: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US,colletoncountysouthcarolina/PST045218, accessed on 8-6-2019

2.6. Conceptual framework of the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention

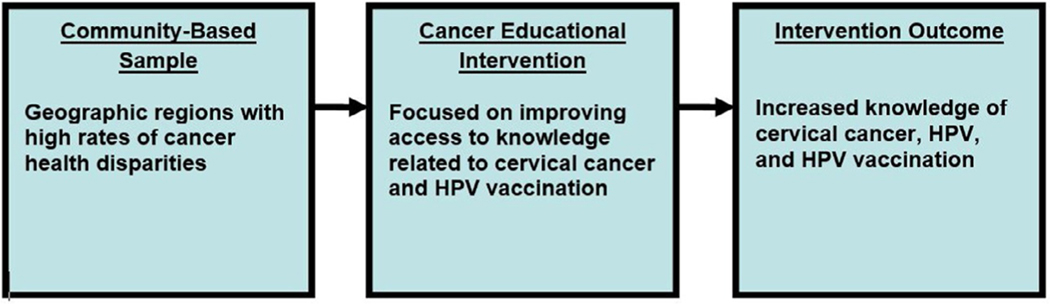

The design of the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention, which includes a cervical cancer and HPV vaccine module, was based on a conceptual framework developed to understand barriers impacting the participation of diverse populations in clinical trials (Swanson & Ward, 1995). These same barriers could negatively impact the likelihood of African American community members participating in educational forums focused on cervical cancer education. The conceptual framework for our study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework.

In the Swanson and Ward (1995) framework, sociocultural barriers are defined as fear and mistrust of research, the investigators conducting the research, or even the institution where the research is conducted (Swanson & Ward, 1995). Sociocultural barriers also include racial and ethnic discrimination, cultural beliefs regarding illness and disease, mistrust of the health care system, and differences in health beliefs and practices (Swanson & Ward, 1995). The sociocultural barriers identified in the Swanson and Ward (1995) framework could deter African American community members from receiving the HPV vaccine. For example, African American parents may mistrust the health care system’s reassurances that the HPV vaccine is safe and effective (Fu et al., 2017).

In the present study, sociocultural barriers were addressed using the following methods. First, the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention was conducted in trusted community venues including churches, libraries, thrift stores, a community action agency, and a cancer center (see Table 3). Second, the investigators also worked with trusted community partners (“Champions,” e.g., civic, religious, and social organizational leaders) who endorsed the study and recruited participants to attend each MOVENUP cancer educational intervention session. Using community-engaged recruitment methods helped to foster a sense of trust among the study participants.

Table 3.

Location, date, and number of participants in the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention by study site (n = 276).a

| SC city (n = 10) | Urban/rural | SC county (n = 9) | Study site (n = 15) | Date of the intervention | Preregistered participants (n = 358) | Intervention participants (n = 274)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock Hill | Urban | York | Mt. Hebron Baptist Church | February 21, 2015 | 25 | 22 |

| St. Helena Island | Rural | Beaufort | St. Helena Island Branch Library | April 16, 2015 | 15 | 9 |

| Orangeburg | Rural | Orangeburg | OCAB Community Action Agency | May 23, 2015 | 25 | 20 |

| Charleston | Urban | Charleston | MUSC Hollings Cancer Center | June 6, 2015 | 26 | 17 |

| Greenville | Urban | Greenville | Buncombe Street United Methodist | August 27, 2016 | 27 | 19 |

| Greenville | Urban | Greenville | Goodwill Industries Thrift Store | October 22, 2016 | 22 | 11 |

| Greenville | Urban | Greenville | Nicholtown Baptist Church | June 23, 2018 | 32 | 27 |

| Pickens | Rural | Pickens | Griffin Ebenezer Baptist Church | July 14, 2018 | 25 | 27 |

| Greenville | Urban | Greenville | Long Branch Baptist Church | July 14, 2018 | 22 | 10 |

| Greenville | Urban | Greenville | Goodwill Industries Thrift Store | October 6, 2018 | 19 | 13 |

| Charleston | Urban | Charleston | Morris Brown AME Church | January 19, 2019 | 32 | 34 |

| Edisto Island | Rural | Charleston | Allen AME Church | March 2, 2019 | 21 | 12 |

| Summerton | Rural | Clarendon | Historic Liberty Hill AME Church |

April 27, 2019 | 25 | 25 |

| Holly Hill | Rural | Orangeburg | Greater Unity AME Church | May 25, 2019 | 21 | 12 |

| Wedgefield | Rural | Sumter | Orangehill AME Church | June 28, 2019 | 21 | 16 |

The response rate was 77% for the intervention participants versus preregistered participants.

Two participants left the training before completing the survey.

Abbreviations: SC, South Carolina; OCAB, Orangeburg-Calhoun-Allendale-Bamberg; MUSC, Medical University of South Carolina; AME, African Methodist Episcopal.

Additionally, each MOVENUP cancer educational intervention session took place in a trusted community venue that was identified and arranged by trusted local community leaders (Champions) in each community setting. The Champions were responsible for recruiting the participants for the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention trainings. Moreover, many of the investigative team members were African American, and therefore may have been more relatable to the study participants. Finally, as part of the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention, past clinical trial and ethical violations and abuses documented in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and the Henrietta Lacks cell line controversy were presented to explain how research protections eventually led to the current high levels of protection of participants in contemporary research studies (e.g., the informed consent process, consent forms, and Data and Safety Monitoring Committees).

2.7. Measurement instrument

The study outcome was defined as a significant pre-test/post-test change in knowledge related to cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine. A six-item investigator-developed instrument was used to evaluate these changes in knowledge. The questions were based on the investigators’ review of the contemporary literature on the topic of cervical cancer and HPV infection and included a mix of True/False and multiple choice questions (see Table 4). An overall knowledge score was also calculated that ranged from 0 to 6 for the total of the six questions, based on one point per each correctly answered question.

Table 4.

Study instrument assessing cervical cancer, HPV, and HPV vaccination knowledge.

| Quiz evaluating cervical cancer, HPV, and HPV vaccination knowledge | |

|---|---|

| Question 1. A Papanicolaou (Pap) test is a screening test for (circle one answer, a–e): a. Breast Cancer b. Colorectal Cancer c. Prostate Cancer d. Cervical Cancer e. None of the Above |

Question 4. HPV is transmitted through (circle one answer, a–c): a. Skin-to-skin sexual contact b. Shaking hands with an HPV infected person c. Coming in contact with the blood of an HPV-infected person |

| Question 2. What is the major cause of cervical cancer (circle one answer, a–d): a. Hepatitis A b. Human Immunodeficiency Virus c. Human Papilloma Virus d. Influenza |

Question 5. Only females can receive the HPV vaccine (circle one answer, True or False): a. True b. False |

| Question 3. Having an HPV infection means that you will get cervical cancer (circle one answer, True or False): a. True b. False |

Question 6. Only sexually active individuals can receive the HPV vaccine (circle one answer, True or False): a. True b. False |

Two items assessed cervical cancer knowledge,

Two items evaluated HPV knowledge, and

Two items assessed HPV vaccination knowledge.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages were reported for demographic variables. Pre- and post-intervention changes in cervical cancer, HPV, and HPV vaccine knowledge were assessed by McNemar’s test of agreement for paired data. Regression analyses assessed the associations of demographic variables (e.g., education, income) and the overall knowledge score. SAS Version 9.4 was used to perform analyses (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3. Results

Study sites included a number of churches, one library, two thrift stores, one community action agency, and a cancer center. The number of participants at each site varied from 9 to 34, with an average of 18 participants per site (Table 3).

Table 5 provides a summary of the demographic characteristics of the 276 study participants (93% African American). Most of the participants (73%) who reported age were 50 years of age or older. Among those who reported gender and income, 91% were female and 46% had an annual household income <$40,000. Forty-nine percent of the participants who reported their educational level had not graduated from college.

Table 5.

Summary of demographic characteristics of participants at pre-test (n = 276).

| Variable | n % |

|---|---|

| Age (years)a (n = 270) | |

| <50 | 74 (27.4) |

| 51–64 | 94 (34.8) |

| 65+ | 102 (37.8) |

| Gendera (n = 161) | |

| Male | 15 (9.3) |

| Female | 146 (90.7) |

| Hispanic ethnicity (Yes/No)a (n = 274) | |

| Yes | 3 (1.1) |

| No | 271 (98.9) |

| Racea (n = 274) | |

| African American or Black | 255 (93.1) |

| White | 17 (6.2) |

| Otherb | 2 (0.8) |

| Educationa (n = 272) | |

| Less than high school | 9 (3.34) |

| High school—some college | 125 (45.9) |

| College graduate or more | 138 (50.8) |

| Marital statusa (n = 270) | |

| Married or living as married | 114 (42.2) |

| Widowed | 39 (14.4) |

| Divorced/Separated | 55 (20.4) |

| Never married | 62 (23.0) |

| Household income (USD) (n = 261) | |

| 0–19,999 | 57 (21.8) |

| 20,000–39,999 | 63 (24.1) |

| 40,000–59,999 | 65 (25.0) |

| 60,000–79,999 | 29 (11.1) |

| ≥80,000 | 47 (18.0) |

Missing data on this variable.

Other race included one individual of American Indian or Alaska Native race.

Table 6 reports the outcomes of the cervical cancer questions. Overall, mean (SD) pre- (4.18 [1.42]) and post-test (4.68 [1.55]) scores differed significantly (P < 0.0001). For questions 2, 4, 5, and 6 there was a statistically significant difference between the pre- and post-test scores (P < 0.05). More participants changed from an incorrect to a correct answer for questions 2 and 4, with the greatest change in question 4 (40%) about how HPV was transmitted (skin-to-skin contact). In examining the item analysis, most participants knew the correct answer to question 1, that a Pap test is a screening test for cervical cancer, so there was no change in knowledge at post-test. Likewise, for question 3, most participants knew that having an HPV infection does not necessarily mean a person will develop cervical cancer. At post-test, the average correct response percentage for the 6 questions was 79% (range 74%–83%). In regression models, the demographic variables assessed (age, education, income, urban/rural) were not found to be predictors for the overall knowledge score.

Table 6.

Pre-test/post-test knowledge response changes by question.

| Questions (correct response) | Incorrect to incorrect n (%) | Incorrect to correct n (%) | Correct to incorrect n (%) | Correct to correct n (%) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1: A Papanicolaou (Pap) test is a screening test for … (cervical cancer) | 20 (7.87) | 31 (12.20) | 23 (9.06) | 180 (70.87) | 0.2763 |

| Q2: What is the major cause of cervical cancer? (human papillomavirus) | 33 (12.99) | 53 (20.87) | 16 (6.30) | 152 (59.84) | <0.0001 |

| Q3: Having an HPV infection means that you will get cervical cancer. (False) | 28 (11.02) | 34 (13.39) | 38 (14.96) | 154 (60.63) | 0.6374 |

| Q4: HPV is transmitted through … (skin-to-skin sexual contact) | 61 (24.02) | 101 (39.76) | 9 (3.54) | 83 (32.68) | <0.0001 |

| Q5: Only females can receive the HPV vaccine. (False) | 17 (6.69) | 45 (17.72) | 27 (10.63) | 165 (64.96) | 0.0339 |

| Q6: Only sexually active individuals can receive the HPV vaccine. (False) | 18 (7.09) | 21 (8.27) | 41 (16.14) | 174 (68.5) | 0.0111 |

Statistical significance indicated by P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The MOVENUP cancer educational intervention implemented community-based cancer education in nine counties of South Carolina to engage predominantly African American communities. During each MOVENUP session led by the investigators, important cancer educational topics relevant to African American cancer mortality rates were highlighted.

The results demonstrated that community-delivered cancer education can increase knowledge of cervical cancer in African American communities, and hopefully lead to greater uptake of the HPV vaccine. Given the suboptimal rates of HPV vaccination in South Carolina and disproportionate cervical cancer mortality rates for African American women, there have been statewide efforts to improve HPV vaccination rates and increase adherence to cervical cancer screening through the South Carolina Cancer Alliance and partner institutions (South Carolina Cancer Alliance, 2019). The state cancer plan has a modest goal to increase the HPV vaccination completion rates for 13- to 17-year olds to 50% by the end of 2021 (South Carolina Cancer Alliance, 2019). The MOVENUP cancer educational intervention complements these efforts with its focus on community-engaged educational approaches in African American communities with limited access to cancer educational information. The MOVENUP investigators, with funding from the National Cancer Institute, are now developing strategies to link their educational efforts with no-/low-cost HPV vaccination sites in each county.

Investigators from academic institutions in South Carolina are committed to conducting community-engagement strategies to reduce the glaring health disparities in the state. For example, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Report, Principles of Community Engagement, highlights the community engagement work in health-related research in South Carolina (Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, 2011; Wilcox et al., 2007). One example was the Health-e-AME (African Methodist Episcopal) faith-based physical activity initiative. The community identified physical activity as an intervention target to decrease health disparities. This initiative partnered the AME church with the Medical University of South Carolina and the University of South Carolina to increase physical activity in their congregations. Following the initiative, there was high awareness of the intervention among parishioners, and the partnership with the AME church continues to collaborate on public health initiatives.

Another highly recognized academic-community research partnership in South Carolina was Project SuGAR, in which African Americans living in the South Carolina Sea Islands partnered with investigators at the Medical University of South Carolina to research genetic factors involved in diabetes and to engage the community in health education and health screenings for metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, 2011; Hunt et al., 2014). The Project SuGAR Citizen Advisory Committee was established in 1996 and continues to function today and support other community health research projects studying systemic lupus erythematosus and cancer disparities (Spruill et al., 2013; Wolf et al., 2018). These few examples highlight some of the long-term, community-engaged work by academic institutions in South Carolina, and the current study contributes to this literature as another successful example from the field. As in the other examples cited, the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention employed community engagement principles to improve program outcomes specifically related to access to up-to-date cancer educational resources.

The MOVENUP cancer educational intervention successfully built trust with several predominantly African American communities in rural and urban areas of South Carolina and delivered cancer educational interventions in trusted locations to engaged community members. Examples of community partners included leaders from the following organizations: the 7th Episcopal District of the AME Church of South Carolina, the South Carolina Cancer Alliance, and the American Cancer Society. By partnering with the community, the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention created learning opportunities in cancer education to improve cancer knowledge in these communities.

Other studies aiming to increase HPV vaccination knowledge in African American communities have used a community forum approach, which has also been used in community-engaged research on various health topics (Bharmal et al., 2016). For example, Teteh and colleagues reported a significant change in perceived knowledge of HPV and cervical cancer for both African Americans and Hispanics following the delivery of community forums (Teteh et al., 2019). In the analysis of the post-test scores, the authors found that having a regular doctor and trust of vaccines were associated with higher knowledge scores (Teteh et al., 2019). Survey studies with African American communities have found varied results with knowledge of cervical cancer, HPV and the HPV vaccine. A survey study in Chicago with African American women reported that 73% of participants scored less than 65% on the knowledge part of the survey. Variables associated with higher scores (>65%) included education, income, and having a child vaccinated with the HPV vaccine (Strohl et al., 2015). This study was more similar to the present study in that it studied middle-aged women and found low knowledge scores among community members. In the present study, the average correct post-test knowledge score was 78%.

Another survey study conducted in Charleston, South Carolina with Latina immigrant women focused on cervical cancer screening adherence reported that slightly more than half of the sample had heard of the HPV vaccine and two-thirds believed HPV was a sexually transmitted disease (Luque et al., 2018). In this study, factors negatively associated with cervical cancer screening included not knowing where to go to be screened, not having a regular provider and psychosocial factors such as low self-efficacy. What these other studies have in common with the present study is a demonstrated need for not only cervical cancer education in minority communities, but also additional support for healthcare seeking and addressing the challenges of finding a source of regular healthcare.

In summary, while the goal of this study was to evaluate the proportion of people who answered correctly between the pre- and post-test, the study data appear to be trending toward significant improvements in knowledge, particularly for survey items 2 and 4. The post-test results indicated that participants increased their knowledge about cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

There were both strengths and limitations of this research. While the sample was representative of counties with high rates of cervical cancer deaths, a random sampling selection scheme was not used. This could potentially limit the generalizability of the study findings. While the entire state of South Carolina is considered the catchment area of the Medical University of South Carolina Hollings Cancer Center, the MOVENUP cancer educational and outreach intervention focused on counties with sizable African American communities, and the intervention was conducted at only one time point. It is possible that the gains in knowledge related to cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine may not be sustained over time. Booster or refresher sessions may be needed in the future to continue to engage these communities and sustain efforts. However, there were many strengths in the academic-community engagement efforts which empowered the community and increased trust in cancer educational research.

Most of the participants were women, who typically serve as the gate-keepers for their family’s health activities. Our team of investigators has found that women share the health information they gain with their families, including male relatives. Nevertheless, it will be important in the future to make a concerted effort to include more men in the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention. Changes in behavior related to the HPV vaccination were not measured. In a future study, the investigators will use federal and state data sources to evaluate changes in the pre- and post-intervention HPV vaccination rates in the nine counties where the intervention was conducted.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the results of a cancer educational intervention to improve cervical cancer knowledge among predominantly African American communities in South Carolina. The study results show that overall, the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention led to significant increases in knowledge related to cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine. This is especially important for content with which the participants may not have previously been familiar. However, for a few of the items on the study assessment instrument, no significant changes were seen from pre- to post-test. This was largely due to the fact that most participants responded with correct answers at pre-test, leaving little room to improve. As noted above, to measure the behavioral impact of the MOVENUP cancer educational intervention, the investigators will analyze federal and state data to evaluate changes in HPV vaccination uptake rates in the nine counties where the intervention was conducted.

Acknowledgments

NIH/NCI R25 CA193088—South Carolina Cancer Health Equity Consortium (SC CHEC): Summer Undergraduate Research Training Program.

NIH/NCI P30CA138313-10S2—Medical University of South Carolina Cancer Center Support Grant Administrative Supplement to Strengthen NCI Supported Community Outreach Capacity through Community Health Educators (CHEs) of the National Outreach Network (NON).

NIH/NCI P20CA157071—South Carolina Cancer Disparities Research Center. NIH/NIMHD R01MD005892—Improving Resection Rates among African Americans with NSCLC, NIH/NCI U54CA210962—South Carolina Cancer Disparities Research Center, NIH/NCATS.

UL1TR001450—South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute (SCTR), and P30CA138313—Medical University of South Carolina/Cancer Center Support Grant.

The current study incorporated a modified version of a cancer educational intervention that was developed by the South Carolina Cancer Alliance for use by general audiences. This educational intervention which initially focused on general knowledge of cancer was expanded to also include knowledge of cancer clinical trials, cervical cancer (including HPV and HPV vaccination), and prostate cancer. These three components were added to the educational intervention due to disparities in cancer incidence and mortality.

References

- American Cancer Society. (2016). Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2016–2018. Retrieved from Atlanta, GA https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans-2016-2018.pdf.

- American Cancer Society. (2019). Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2019–2021. Retrieved from Atlanta, GAhttps://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans-2019-2021.pdf.

- Bharmal N, Lucas-Wright AA, Vassar SD, Jones F, Jones L, Wells R, et al. (2016). A community engagement symposium to prevent and improve stroke outcomes in diverse communities. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 10(1), 149–158. 10.1353/cpr.2016.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). CDC vital signs. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2014-11-vitalsigns.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Genital HPV infection—CDC fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/HPV-FS-print.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Immunization schedules. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/child-adolescent.html#note-hpv.

- Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. (2011). Principles of community engagement [11–7782] National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf.

- Ferris DG, Samakoses R, Block SL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Restrepo JA, Mehlsen J, et al. (2017). 4-valent human papillomavirus (4vHPV) vaccine in preadolescents and adolescents after 10 years. Pediatrics, 140(6). 10.1542/peds.2016-3947. pii: e20163947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ME, Wahlquist AE, Ridgeway C, Streets J, Mitchum KA, Harper RR Jr., et al. (2011). Evaluating an intervention to increase cancer knowledge in racially diverse communities in South Carolina. Patient Education and Counseling, 83(2), 256–260. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu LY, Zimet GD, Latkin CA, & Joseph JG (2017). Associations of trust and healthcare provider advice with HPV vaccine acceptance among African American parents. Vaccine, 35(5), 802–807. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, & Brewer NT (2016). Provider communication and HPV vaccination: The impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine, 34(9), 1187–1192. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt KJ, Kistner-Griffin E, Spruill I, Teklehaimanot AA, Garvey WT, Sale M, et al. (2014). Cardiovascular risk in Gullah African Americans with high familial risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Project SuGAR. Southern Medical Journal, 107(10), 607–614. 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake PW, Kasting ML, Christy SM, & Vadaparampil ST (2019). Provider perspectives on multilevel barriers to HPV vaccination. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(7–8), 1784–1793. 10.1080/21645515.2019.1581554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazcano-Ponce E, Torres-Ibarra L, Cruz-Valdez A, Salmeron J, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Prado-Galbarro J, et al. (2019). Persistence of immunity when using different human papillomavirus vaccination schedules and booster-dose effects 5 years after primary vaccination. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 219(1), 41–49. 10.1093/infdis/jiy465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopalco PL (2017). Spotlight on the 9-valent HPV vaccine. Drug Design, Development and Therapy, 11, 35–44. 10.2147/DDDT.S91018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque JS, Tarasenko YN, Li H, Davila CB, Knight RN, & Alcantar RE (2018). Utilization of cervical cancer screening among Hispanic immigrant women in coastal South Carolina. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(3), 588–597. 10.1007/s40615-017-0404-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JX, Royston KJ, Langston ME, Griffin R, Hidalgo B, Wang HE, et al. (2018). Mapping hot spots of breast cancer mortality in the United States: Place matters for Blacks and Hispanics. Cancer Causes & Control, 29(8), 737–750. 10.1007/s10552-018-1051-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselwhite LW, Oliveira CM, Kwaramba T, de Paula Pantano N, Smith JS, Fregnani JH, et al. (2016). Racial/ethnic disparities in cervical cancer screening and outcomes. Acta Cytologica, 60(6), 518–526. 10.1159/000452240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. (2019). SEER cancer stat facts: Cervical cancer. Retrieved from https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html.

- Noronha AS, Markowitz LE, & Dunne EF (2014). Systematic review of human papillomavirus vaccine coadministration. Vaccine, 32(23), 2670–2674. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, & Jemal A. (2019). Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(1), 7–34. 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JS, Brewer NT, Saslow D, Alexander K, Chernofsky MR, Crosby R, et al. (2013). Recommendations for a national agenda to substantially reduce cervical cancer. Cancer Causes & Control, 24(8), 1583–1593. 10.1007/s10552-013-0235-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South Carolina Cancer Alliance. (2019). Services and initiatives, cervical cancer. Retrieved from https://www.sccancer.org/initiatives/cervical-cancer/.

- South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. Public Health Statistics and Information Services: Division of Biostatistics and Health GIS. (2019a). SCAN cancer incidence. Full (Research) File. Retrieved from http://scangis.dhec.sc.gov/scan/cancer2/fullinput.aspx.

- South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. Public Health Statistics and Information Services: Division of Biostatistics and Health GIS. (2019b). SCAN cancer mortality. Retrieved from http://scangis.dhec.sc.gov/scan/cancer2/mortinput.aspx.

- Spruill IJ, Leite RS, Fernandes JK, Kamen DL, Ford ME, Jenkins C, et al. (2013). Successes, challenges and lessons learned: Community-engaged research with South Carolina’s Gullah population. Gateways, 6. 10.5130/ijcre.v6i1.2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohl AE, Mendoza G, Ghant MS, Cameron KA, Simon MA, Schink JC, et al. (2015). Barriers to prevention: Knowledge of HPV, cervical cancer, and HPV vaccinations among African American women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 212(1), 65. e61–65. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson GM, & Ward AJ (1995). Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: Toward a participant-friendly system. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 87(23), 1747–1759. 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teteh DK, Dawkins-Moultin L, Robinson C, LaGroon V, Hooker S, Alexander K, et al. (2019). Use of community forums to increase knowledge of HPV and cervical cancer in African American communities. Journal of Community Health, 44(3), 492–499. 10.1007/s10900-019-00665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsu VD, & Ginsburg O. (2017). The investment case for cervical cancer elimination. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 138(Suppl. 1), 69–73. 10.1002/ijgo.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Fredua B, et al. (2017). National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(33), 874–882. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6633a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Fredua B, et al. (2019). National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2018. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(33), 718–723. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Laken M, Anderson T, Bopp M, Bryant D, Carter R, et al. (2007). The health-e-AME faith-based physical activity initiative: Description and baseline findings. Health Promotion Practice, 8(1), 69–78. 10.1177/1524839905278902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf BJ, Ramos PS, Hyer JM, Ramakrishnan V, Gilkeson GS, Hardiman G, et al. (2018). An analytic approach using candidate gene selection and logic Forest to identify gene by environment interactions (GE) for systemic lupus erythematosus in African Americans. Genes (Basel), 9(10). 10.3390/genes9100496. pii: E496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]