Abstract

A group of 76 consecutive human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients with fever of unknown origin (n = 52) or fever associated with pulmonary diseases was evaluated in order to assess the usefulness of PCR with peripheral blood in the diagnosis and follow-up of visceral leishmaniasis. We identified 10 cases of visceral leishmaniasis among the 52 patients with fever of unknown origin. At the time of diagnosis, all were parasitemic by PCR with peripheral blood. During follow-up, a progressive decline in parasitemia was observed under therapy, and all patients became PCR negative after a median of 5 weeks (range, 6 to 21 weeks). However, in eight of nine patients monitored for a median period of 88 weeks (range, 33 to 110 weeks), visceral leishmaniasis relapsed, with positive results by PCR with peripheral blood reappearing 1 to 2 weeks before the clinical onset of disease. Eight Leishmania infantum and two Leishmania donovani infections were identified by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. PCR with peripheral blood is a reliable method for diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients. During follow-up, it substantially reduces the need for traditional invasive tests to assess parasitological response, while a positive PCR result is predictive of clinical relapse.

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is increasingly reported in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive subjects living in the countries of the Mediterranean basin, especially Spain, Italy, and France, where over 90% of the published cases have been observed (1, 20). The diagnosis of VL among HIV-positive patients is hampered by the lack of specific signs and symptoms, unreliable serology, and poor sensitivity of direct microscopic diagnosis (1, 8). Furthermore, bone marrow aspirations and biopsies are invasive procedures, and in vitro parasite isolation is difficult and time-consuming. Recently, PCR with peripheral blood, bone marrow aspirates, and lymph node or spleen biopsy specimens of immunocompromised patients has proved to be more rapid, sensitive, and specific than the traditional diagnostic methods (5, 9, 11, 12, 15, 18).

In the present study, VL has been diagnosed by means of microscopic demonstration of Leishmania in bone marrow and/or the buffy coat from peripheral blood and/or by culture in blood-based medium (4). We considered VL highly probable in patients without parasitological evidence of Leishmania but with suggestive clinical signs and symptoms and/or significantly positive indirect fluorescent-antibody test (IFAT) titers (≥1:80).

Between January 1997 and August 1999, we enrolled 76 HIV-positive subjects (CD4+-cell counts, ≤200/μl) with fever of unknown origin (FUO) (n = 52) or fever associated with radiological evidence of pulmonary disease (PDs) (n = 24) (Table 1). As an additional control group, peripheral blood samples from 143 healthy blood donors attending two different transfusion centers in Milan, Italy, were also included in the study.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and laboratory features of population studied

| Feature | No. (%) of patientsa

|

|

|---|---|---|

| FUO (n = 52) | PD (n = 24) | |

| Male | 41 (85.4) | 18 (75) |

| Intravenous drug user | 36 (69.2) | 18 (75) |

| No. of CD4 cells/μl (median [range]) | 98 (1–200) | 82 (1–200) |

| Patients with the following no. of CD4 cells/μl | ||

| <50 | 17 (35.5) | 8 (33.4) |

| 51–100 | 8 (16.6) | 5 (20.8) |

| 101–200 | 23 (47.9) | 11 (45.8) |

| No. of HIV RNA copies/ml (median [range]) | 5,000 (200–900,000) | 10,000 (400–800,000) |

| Patients with <500 HIV RNA copies/ml | 16 (33.3) | 7 (29.2) |

| Treatment with HAART | 25 (52) | 12 (50) |

| Previous AIDS diagnosis | 29 (60.4) | 12 (50) |

| Signs and symptoms | ||

| Fever | 48 (100) | 24 (100) |

| Anemia | 32 (66.6) | 7 (14.6) |

| Splenomegaly | 30 (62.5) | 6 (12.5) |

| Hepatomegaly | 28 (58.3) | 7 (14.6) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 10 (20.8) | 2 (8.3) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 18 (37.5) | 5 (20.8) |

| Neutropenia | 15 (31.2) | 5 (20.8) |

| Final diagnosis | ||

| Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection | 17 (35.4) | |

| VL | 10 (18.8) | |

| Cytomegalovirus infection | 9 (12.6) | |

| FUO | 5 (10.4) | |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 4 (8.3) | |

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | 4 (8.3) | |

| Extrapulmonary tuberculosis | 3 (6.2) | |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 19 (79.2) | |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 5 (20.8) | |

Unless indicated otherwise.

The DNA extracted from 300 μl of EDTA-anticoagulated peripheral blood and bone marrow aspirate was assayed by means of a Leishmania-specific PCR. One microgram of extracted DNA was loaded into each PCR mixture.

A linearized plasmid (kindly provided by J. Eckert, Institute of Parasitology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland) containing the complete Leishmania infantum small-subunit (SSU) rRNA gene was used to assess PCR sensitivity. As PCR and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis-positive controls, we used promastigotes of four Leishmania reference strains: L. infantum zymodeme MON1 (MHOM/TN/IPT1), Leishmania donovani zymodeme MON2 (MHOM/IN/80/DD8), Leishmania tropica zymodeme MON60 (MHOM/SU/74/K27), and L. major zymodeme MON4 (MHOM/SU/73/5ASKH). The promastigote pellets were resuspended in 600 μl of proteinase K (120 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) digestion buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.0], 0.5% Tween 20, 0.5% Nonidet P-40 [all reagents were from Sigma]), and the mixture was incubated at 56°C overnight. After inactivation of the proteinase K at 95°C for 15 min, the crude lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min and 5 μl of the supernatant was used in each PCR mixture.

The presence and integrity of human DNA in the extracted samples were assessed by amplifying a 252-bp fragment of the β-globin gene with the following primers: hβ3if (5′-CGGCTGTCATCACTTAGACCTC-3′) and hβ4ir (5′-CTTCATCCACGTTCACCTTGC-3′). PCR for the SSU rRNA gene of Leishmania involved the use of the R223 and R333 set of primers, originally described by van Eys et al. (18), which amplify a 359-bp fragment of the SSU rRNA genes of the different Leishmania taxa. PCRs were performed in a final volume of 100 μl containing 1 μg of template DNA (or 5 μl of crude lysate), each primer at a concentration of 0.2 μM, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 2.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1× PCR Buffer II (Perkin-Elmer). Cycling parameters were as follows: initial denaturation of 9 min at 94°C; 10 cycles at 94°C for 30 s and 60°C for 1 min, with a 1-s increment per cycle; 40 cycles of 10 s at 94°C, followed by 70 s at 60°C, with a 1-s increment per cycle; and a final 7 min of incubation at 72°C, which terminated the reaction. PCR products were visualized by UV-light exposure after standard agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining.

PCR sensitivity was assessed by the limiting dilution method and signal distribution analysis as described elsewhere and was five copies of each PCR target (i.e., Leishmania and human β-globin) (13; Z. Wang, and J. Spadoro, Abstr. 94th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. D-256, p. 141, 1994).

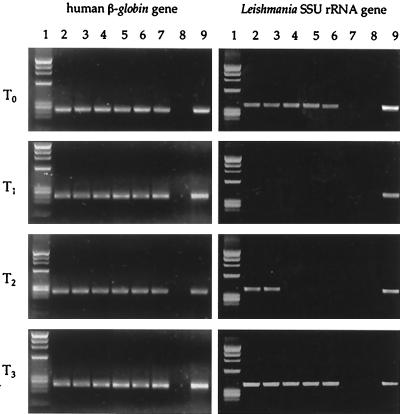

In order to estimate the parasite burden in peripheral blood and bone marrow samples, six 10-fold serial dilutions of the extracted DNA were performed. Each dilution sample separately underwent amplification with human β-globin and Leishmania-specific primers (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Leishmania burden in patient 1, estimated by semiquantitative PCR with peripheral blood. Six serial 10-fold dilutions of the extracted DNA separately underwent amplification with human β-globin and Leishmania-specific primers. Lane 1, molecular weight marker; lanes 2 to 7, serial 10-fold dilutions from 1 μg to 1 pg of target DNA; lane 8, negative control; lane 9, positive control. T0, time of clinical presentation with VL (fever, pancytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly); T1, 2 weeks following successful treatment with a negative result by PCR with peripheral blood; T2, time of follow-up at 34 weeks with reappearance of a positive PCR result without clinical symptoms of VL; T3, time of follow-up at 36 weeks with an increase in the parasite burden and the reappearance of symptoms of VL.

The quantification results for the positive samples by the serial dilution PCR (Fig. 1 and 2) were arbitrarily expressed as the number of Leishmania parasites per 5 × 106 peripheral blood leukocytes, assuming that each parasite harbors 160 copies of the SSU rRNA gene (18). Negative samples were considered to have less than 1 parasite per 150,000 leukocytes (i.e., 1 μg of DNA extracted from peripheral blood).

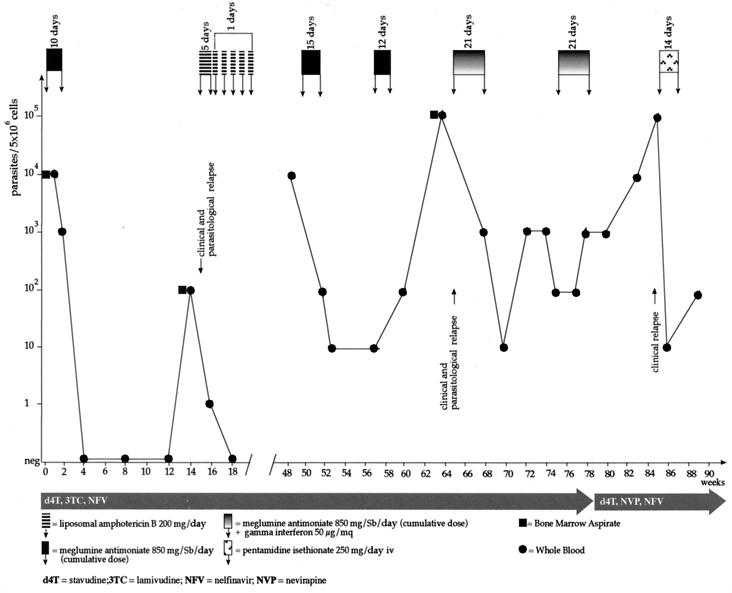

FIG. 2.

Graphic representation of the course of VL in patient 2. The increase in the parasite burden is followed by the reappearance of symptoms (clinical and parasitological relapse). Circles, PCR performed with peripheral blood; squares, PCR performed with bone marrow aspirates; iv, intravenous; Sb, antimony.

Identification of the Leishmania to the species level was obtained by PCR-RFLP analysis of a Leishmania-specific nuclear repetitive genomic sequence as described by Minodier et al. (9).

Leishmania stocks isolated in vitro were characterized by means of starch gel electrophoretic analysis of 15 isoenzymes (malate dehydrogenase [EC 1.1.1.3.7], malic enzyme [EC 1.1.1.4.0], isocitrate dehydrogenase [EC 1.1.1.4.2], 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase [EC 1.1.1.4.4], glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase [EC 1.1.1.4.9], glutamate dehydrogenase [EC 1.4.1.3], diaphorase NAD [reduced form] [EC 1.6.2.2], two isoforms of purine-nucleoside phosphorylase [EC 2.4.2.1], two isoforms of glutamate-oxoloacetate transaminase [EC 2.6.1.1], phosphoglucomutase [EC 2.7.5.1], fumarate hydratase [EC 4.2.1.2], mannose phosphate isomerase [EC 5.3.1.8], and glucose phosphate isomerase [EC 5.3.1.9]) as described previously (7), using three Leishmania reference strains: MHOM/TN/80/IPT1 for L. infantum zymodeme MON1, MHOM/IN/80/DD8 for L. donovani zymodeme MON2, and MHOM/ET/93/IPB-096 for L. donovani zymodeme MON37.

The Leishmania-specific PCR was negative for the 24 samples of peripheral blood and 10 bone marrow aspirates obtained from the control subjects with PD and the 143 blood specimens from healthy blood donors. PCR was performed with 52 samples of peripheral blood and 31 bone marrow aspirates from the 52 patients with FUO.

Among the subjects with FUO, a definitive diagnosis of VL was obtained for nine subjects and a diagnosis of probable VL was obtained for 1 subject (patient 10) (Table 2). This patient received anti-Leishmania treatment, and after 66 weeks he suffered a clinical relapse, during which Leishmania parasites could be microscopically demonstrated in the bone marrow.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of HIV-seropositive patients with VLa

| Parameter | Trait or result for patient no.:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3b | 4 | 5c | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9d | 10 | |

| Age (yrs) | 45 | 33 | 32 | 28 | 31 | 37 | 38 | 27 | 29 | 32 |

| Sex | M | F | F | M | M | M | M | M | M | M |

| HIV risk factor | IVDU | IVDU | Hetero | IVDU | IVDU | IVDU | IVDU | IVDU | Hetero | IVDU |

| HIV stage | C3 | C3 | C3 | C3 | B3 | B3 | C3 | C3 | C3 | C2 |

| CD4 (no. of cells/μl) | 10 | 78 | 4 | 158 | 94 | 82 | 6 | 62 | 10 | 190 |

| HIV-RNA (no. of copies/ml) | <500 | <500 | 1,000,000 | 27,000 | 800,000 | 4,900 | <500 | 3,750 | 107,000 | 54,000 |

| HAART at the time of VL diagnosis | d4T, 3TC, IDV | d4T, 3TC, IDV | No | No | No | AZT, 3TC, IDV | d4T, NVP, IDV | d4T, 3TC, RTV | No | No |

| Primary VL diagnosis (no. of wks from primary VL to VL relapse) | No (44) | Yes | No (76) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No (40) | No (188) | Yes | Yes |

| Follow-up (no. of wks) | 75 | 88 | 6 | 94 | 6 | 30 | 88 | 100 | 6 | 110 |

| VL relapse(s) (no. of wks) | 32, 52 | 14, 48, 63, 84 | 44 | 73, 95 | 36 | 105 | ||||

| IFAT serology and titer | Pos, 1:320 | Pos, 1:80 | Pos, 1:1,280 | Neg | Pos, 1:256,000 | NA | Neg | Pos, 1:80 | Neg | Pos, 1:80 |

| Microscopy result (sample[s]) | Pos (Bm, Gb) | Pos (Bm) | Pos (Pe) | Pos (Bm) | Pos (Bm) | Pos (Bm) | Pos (Bm) | ND | Pos (Bm, Eb) | Neg (Bm) |

| Culture result (sample) and Leishmania isoenzyme characterization | Pos (Bm), Leishmania spp. | Pos (Bm), L. donovani MON37 | NA | Neg (Bm) | Pos (Bm), Leishmania spp. | NA | Pos (Bm, Wb), L. infantum MON1 | Pos (Wb), L. infantum MON1 | Neg (Bm) | NA |

| PCR-RFLP analysis result | L. donovani | L. donovani | L. infantum | L. infantum | L. infantum | L. infantum | L. infantum | L. infantum | L. infantum | L. infantum |

| Wb PCR result | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos |

| Bm PCR result | Pos | Pos | ND | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | ND | Pos | NA |

| Biopsy PCR (sample) | Pos (Gb) | Pos (Pe) | Pos (Eb) | |||||||

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; IVDU, intravenous drug user; Hetero, heterosexual transmission; Bm, bone marrow; Wb, whole blood; Gb, gastric biopsy; Eb, esophageal biopsy; Pe, pleural effusion; NA, not available; ND, not done; d4T, stavudine; 3TC, lamivudine; AZT, zidovudine; IDV, indinavir; RTV, ritonavir; NVP, nevirapine.

Patient died 7 weeks after VL diagnosis from P. carinii pneumonia.

Patient died 21 weeks after VL diagnosis from Kaposi's sarcoma.

Patient died 51 weeks after VL diagnosis from non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

PCR-RFLP analysis for Leishmania species identification was performed for all patients. A single 250-bp band suggestive of L. infantum infection was observed for eight subjects, while two bands of 180 and 70 bp, a characteristic pattern of L. donovani, were evident for two subjects (patients 1 and 2).

Four Leishmania stocks were obtained in culture, three of which underwent identification by isoenzyme analysis: two isolates were identified as L. infantum zymodeme MON1 (isolates 7 and 8) and one was identified as L. donovani zymodeme MON37 (isolate 2), thus confirming the identification obtained by the molecular technique, PCR-RFLP analysis.

All patients affected by VL received one of the following treatments at standard doses: meglumine antimoniate (four patients), liposomal amphotericin B (three patients), or amphotericin B desoxycholate (three patients).

A follow-up semiquantitative PCR with peripheral blood showed a progressive reduction in the circulating parasite burden while the patients were receiving therapy: 9 of the 10 patients were negative after 14 weeks, while 1 (patient 7) was negative after 21 weeks. Eight patients with HIV-VL coinfection were monitored for a median period of 88 weeks (range, 30 to 110 weeks). Semiquantitative PCR was performed monthly with peripheral blood samples. In all cases Leishmania parasitemia detected by PCR was associated with clinical relapse but preceded the reappearance of symptoms by a mean period of 1 to 2 weeks (Fig. 2). During follow-up, 3 patients died a median of 21 weeks after the diagnosis of VL (range, 7 to 51 weeks): patient 3 died of pulmonary failure due to Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, patient 5 died of disseminated Kaposi's sarcoma, and patient 9 died of pulmonary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

At the time of the diagnosis of VL, 5 of 10 patients (patients 1, 2, 6, 7, and 8) were receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), but sustained suppression of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) replication (i.e., ≤500 copies of HIV RNA/ml) was present in only three patients. During follow-up, HAART was initiated in two patients (patients 4 and 9) and was changed in four patients (patients 1, 2, 6, and 8). VL relapsed in patients with virological suppression of HIV-1 replication (patients 1 and 2), as well as in those showing no virological response to HAART (patients 6, 7, and 8).

In all but one patient, CD4+-cell counts remained below the absolute value of 200/μl. The only patient (patient 4) who remained relapse-free and who was uninterruptedly negative as determined by PCR with peripheral blood after 114 weeks of follow-up showed progressive immune reconstitution under HAART, as demonstrated by increasing CD4 T-cell counts (496/μl after 94 weeks and 850/μl at the last follow-up visit).

Previous studies of HIV-infected patients have demonstrated that the sensitivity of PCR for the diagnosis of VL ranges from 82 to 98% (3, 12, 14, 15). Our findings confirm this sensitivity for individuals coinfected with HIV-1 and also provide further evidence that the altered immune response in patients with HIV-Leishmania coinfection not only is responsible for the persistence of parasites, despite a clinical response to specific therapy, but also favors blood dissemination, as documented by a positive result by PCR with peripheral blood (7, 10, 19).

Furthermore, quantitation of parasitemia by PCR is extremely useful in monitoring treatment efficacy and predicting relapse. In this regard, our data are in agreement with and complement the findings of a recent study performed in France in which qualitative PCR with peripheral blood was used in the diagnosis and follow-up of VL in both immunosuppressed and immunocompetent patients (5). Although all of our patients had a negative result by PCR with peripheral blood 6 to 21 weeks after completion of antileishmania treatment, all but one experienced a resurgence of parasitemia, and importantly, the increase in the parasite burden correlated with clinical disease relapse. From a pathogenic point of view, these results show that a parasitological cure is seldom achieved in HIV-infected patients with VL, even when a control bone marrow aspiration performed after the completion of treatment fails to reveal Leishmania amastigotes. From a clinical standpoint, we confirm the findings of Lachaud et al. (5) that a positive result by PCR with peripheral blood is indicative of the presence of viable Leishmania parasites since it correlates with clinical disease. We observed VL relapses among the patients responding well or not at all to HAART, although the only patient who remained free of relapse after 2 years of follow-up showed the best immunological response (a progressive increase in CD4+-lymphocyte counts to above 800/μl), thus indirectly confirming the fact that the cytokines produced by specific subsets of CD4+ cells play a prominent role in promoting protective immunity against parasitic infections.

Our preliminary results seem to indicate a good degree of correlation between the results of PCR-RFLP analysis and those of the traditional methods of species characterization. Although isoenzyme characterization was used only for three Leishmania strains, it confirmed the identification obtained by PCR-RFLP analysis. As expected on the basis of previous findings (1), VL was prevalently caused by L. infantum, the common agent of VL in the Mediterranean basin, but it is noteworthy that one patient was infected with L. donovani (zymodeme MON37), a species that is not considered endemic in the Mediterranean area. However, the presence of this species has recently been suspected in the Middle East (2, 16, 17). Our patient had a long history of worldwide travel and drug addiction and may have acquired the infection during a trip to Turkey about 10 years before VL was diagnosed or as a result of mechanical transmission between intravenous drug users, as suspected in the case of a Portuguese patient with L. donovani infection (2).

In conclusion, PCR seems to be one of the most sensitive means of detecting Leishmania spp. among HIV-infected patients. The presence of a positive result by PCR with peripheral blood is always associated with clinical disease. This method could be used as an alternative, noninvasive method of screening individuals with suspected VL or as a tool for monitoring the efficacy of treatment and the appearance of relapse of subclinical disease. Finally, it allows rapid decision making in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of HIV-infected patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvar J, Canavate C, Gutierrez-Solar B, Jiménez M, Laguna F, Lopez-Vélez R, Molina R, Moreno J. Leishmania and human immunodeficiency virus coinfection: the first 10 years. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:298–319. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.2.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campino L, Santos-Gomes G, Pratlong F, Dedet J P, Abranches P. The isolation of Leishmania donovani MON18 from an AIDS patient in Portugal: possible needle transmission. Parasite. 1994;1:391–392. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1994014391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa J M, Durand R, Deniau M, Rivollet D, Izri M, Houin R, Vidaud M, Bretagne S. PCR enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1831–1833. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1831-1833.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gramiccia M, Gradoni L, Troiani M. Heterogeneity among zymodemes of Leishmania infantum from HIV-positive patients with visceral leishmaniasis in south Italy. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;128:33–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lachaud L, Dereure J, Chabbert E, Reynes J, Mauboussin J-M, Oziol E, Dedet J-P, Bastien P. Optimized PCR using patient blood samples for diagnosis and follow-up of visceral leishmaniasis, with special reference to AIDS patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:236–240. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.236-240.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Looker D, Miller L A, Elwood H J, Stickel S, Sogin M L. Primary structure of the Leishmania donovani small subunit ribosomal RNA coding region. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;16:7198. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.14.7198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez-Velez R, Laguna F, Alvar J, Pérez-Molina J A, Molina R, Martinez P, Villarrubia J. Parasitic culture of buffy coat for diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:937–939. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.937-939.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medrano F J, Canavate C, Leal M, Rey C, Lissen E, Alvar J. The role of serology in the diagnosis and prognosis of visceral leishmaniasis in patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:155–162. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minodier P, Piarroux R, Gambarelli F, Joblet C, Dumon H. Rapid identification of causative species in patients with Old World leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2551–2555. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2551-2555.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molina R, Canavate C, Cercenado E, Laguna F, Lopez-Velez R, Alvar J. Indirect xenodiagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in 10 HIV-infected patients using colonized Phlebotomus perniciosus. AIDS. 1994;8:277–279. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199402000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuzum E, White F, Thakur C, Dietze R, Wages J, Grogl M, Berman J. Diagnosis of symptomatic visceral leishmaniasis by use of the polymerase chain reaction on patient blood. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:751–754. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osman O F, Oskam L, Zijlistra E E, Kroon N C M, Schoone G J, Khalil E A G, El-Hassan A M, Kager P A. Evaluation of PCR for diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2454–2457. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2454-2457.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parravicini C, Lauri E, Baldini L, Neri A, Poli F, Sirchia G, Moroni M, Galli M, Corbellino M. Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus infection and multiple myeloma. Science. 1997;278:1969–1970. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5345.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piarroux R, Gambarelli F, Dumon H, Fonets M, Duncan S, Mary C, Toga B, Quilici M. Comparison of PCR with direct examination of bone marrow aspiration, myeloculture, and serology for diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in immunocompromised patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:746–749. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.746-749.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piarroux R, Gambarelli F, Toga B, Dumon H, Fontes M, Dunan S, Quilici M. Interest and reliability of a polymerase chain reaction on bone marrow samples in the diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in AIDS. AIDS. 1996;10:452–453. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199604000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qubain H I, Saliba E K, Oskam L. Visceral leishmaniasis from Bal'a, Palestine, caused by Leishmania donovani s.l. identified through polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Acta Trop. 1997;68:121–128. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rioux J A, Lèger N, Haddad N. Infestation naturelle de Phlebotomus tobbi (Diptera, Psychodidae) par Leishmania donovani s. st. (Kinetoplastida, Trypanosomatidae), en Syrie. Parassitologia. 1998;40:148. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Eys G J J M, Shoone G J, Kroon N C M, Ebeling S B. Sequence analysis of small subunit ribosomal RNA genes and its use for detection and identification of Leishmania parasites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;51:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolday D, Berhe N, Akuffo H, Britton S. Leishmania-HIV interaction: immunopathogenic mechanisms. Parasitol Today. 1998;15:182–187. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Leishmania-HIV coinfection south western Europe 1990–1998 retrospective cases. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1999;74:365–375. [Google Scholar]