Abstract

In this report, we present a PCR protocol for rapid identification of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli on a LightCycler instrument. In a multiplex assay, the genes encoding Shiga toxin 1 and Shiga toxin 2 are detected in a single reaction capillary. A complete analysis of up to 32 samples takes about 45 min.

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC), a worldwide emerging pathogen responsible for sporadic cases of disease as well as serious outbreaks (18; K. G. Liddell, Letter, Lancet 349:502–503, 1997), is producing one or more Shiga toxins (Stxs). These toxins are subdivided into two major classes, Stx1 and Stx2. Stx2e is an Stx2 variant that is produced mainly by E. coli isolates associated with edema disease in pigs (10), although strains expressing it may also cause hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) in humans (4). EHEC is endemic in cattle and other domestic animals, thereby rendering food, mostly undercooked beef and unpasteurized milk, the main route of infection (2). However, transmission of EHEC from person to person is also possible (11, 13). Effective prevention of the disease is therefore crucially dependent on rapid detection of the causative pathogen. Due to various strain differences, reliable identification of EHEC by culture methods is almost impossible (14). In recent years numerous PCR protocols have been developed that target stx1 and stx2 genes and genes of other EHEC pathogenicity factors (1, 3, 8). One to 10 organisms can be detected per assay (12). Recent developments in PCR technology now allow rapid cycling combined with fluorescence-based identification and verification of PCR products. We are presenting here the first protocol for detection of EHEC on a LightCycler instrument (17). In a multiplex assay, stx1 and stx2 genes are identified in a single reaction capillary. Melting curve analysis allows discrimination between stx2 and stx2e, the gene encoding the pig edema disease toxin. This protocol was validated with 48 pretested Stx-producing E. coli (STEC) isolates from diagnostic samples and 37 negative controls.

Online PCR monitoring with the LightCycler.

The LightCycler system (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) offers two different fluorescence formats. SYBR Green I is a dye that binds unspecifically to double-stranded DNA (16) and hybridization probes, which allows sequence-specific detection by using fluorescence energy transfer (FRET) between two fluorophores (9). Fluorescence is measured in three different channels: F1 (530 nm) for SYBR Green I, F2 (640 nm) for LightCycler Red 640, and F3 (710 nm) for LightCycler Red 705. To obtain a melting curve the samples are denatured at 95°C, cooled to about 50°C, and then slowly heated at a temperature transition rate of 0.2°C/s, while fluorescence is monitored continuously. For improved visualization of melting temperatures, melting peaks are derived from the data obtained during this melting curve routine by plotting the negative derivative of fluorescence over temperature versus temperature [−d(F)/dT versus T].

Bacterial strains and DNA extraction.

We studied 37 Stx-negative strains (Table 1) and 48 STEC strains isolated from human stools and beef samples (Table 2). The latter had been tested for the presence of stx1 and stx2 gene sequences by conventional PCR and gel analysis. The Stx double producer E. coli EDL 933 was the reference strain for optimization of the PCR protocol. One microgram of total DNA from EHEC EDL 933 was calculated to be the genomic equivalent of about 2 × 108 of these organisms, based on a genome size of approximately 4.5 Mb for E. coli. Bacterial DNA was extracted from overnight cultures with a DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

TABLE 1.

Negative controls used in the studya

| Isolate no. | Speciesa | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aeromonas hydrophila | CI |

| 2 | Bacillus subtilis | ATCC 6633 |

| 3 | Bacillus subtilis | ATCC 6051 |

| 4 | Campylobacter coli | CI |

| 5 | Campylobacter jejuni | ATCC 33560 |

| 6 | Candida albicans | ATCC 10231 Typ 3 |

| 7 | Citrobacter freundii | CI |

| 8 | Enterobacter cloacae | CI |

| 9 | Enterococcus faecalis | ATCC 10541 |

| 10 | Enterococcus faecalis | ATCC 19433 |

| 11 | Enterococcus faecalis | CI |

| 12 | Enterococcus faecium | ATCC 19434 |

| 13 | Enterococcus faecium | CI |

| 14 | Escherichia coli | ATCC 18229 |

| 15 | Escherichia coli | ATCC 25922 |

| 16 | Escherichia coli | ATCC 29079 |

| 17 | Escherichia coli | ATCC 35218 |

| 18 | EAEC O42 | CI |

| 19 | EIEC 4608/58 | CI |

| 20 | EPEC 2348/69 | CI |

| 21 | ETEC | CI |

| 22 | Helicobacter cinaedi | CI |

| 23 | Helicobacter pylori | CI |

| 24 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 10031 |

| 25 | Morganella morganii | CI |

| 26 | Plesiomonas shigelloides | CI |

| 27 | Proteus mirabilis | ATCC 1453 |

| 28 | Proteus vulgaris | CI |

| 29 | Pasteurella canis | CI |

| 30 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 27853 |

| 31 | Salmonella enteritidis | CI |

| 32 | Salmonella typhimurium | CI |

| 33 | Shigella flexneri | CI |

| 34 | Staphylococcus aureus | CI |

| 35 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | ATCC 12228 |

| 36 | Streptococcus agalactiae | CI |

| 37 | Yersinia enterocolitica | CI |

CI, clinical isolate; EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; EIEC, enteroinvasive E. coli; EPEC, enteropathogenic E. coli; ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli.

TABLE 2.

EHEC and STEC strains used in the study

| Isolate no. | Laboratory code | LightCycler PCR result

|

Serotype | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 | stx2 | ||||

| 1 | 485/98 | + | − | O145:H− | This study |

| 2 | 531/98 | + | − | O145:H− | This study |

| 3 | 563/98 | + | − | O113 | This study |

| 4 | 633/98 | − | + | O26:H− | This study |

| 5 | 741/98 | − | + | O121:H− | This study |

| 6 | 768/98 | − | + | O30:H21 | This study |

| 7 | 802/98 | − | + | O157:H− | This study |

| 8 | 889/98 | + | − | O26:H− | This study |

| 9 | 959/98 | − | − | ONT:H− | This study |

| 10 | 1115/98 | + | + | O157:H− | This study |

| 11 | 1244/98 | − | + | O6:H8 | This study |

| 12 | 1273/98 | − | + | O6:H8 | This study |

| 13 | 1295/98 | − | + | ONT:H− | This study |

| 14 | 1306/98 | + | + | O157:H− | This study |

| 15 | 1568/98 | + | − | O103:H− | This study |

| 16 | 1613/98 | + | − | ONT | This study |

| 17 | 1695/98 | + | − | O103:H− | This study |

| 18 | 54/99 | + | − | O103:H18 | This study |

| 19 | 90/99 | − | + | O157:H− | This study |

| 20 | 109/99 | − | + | O157:H− | This study |

| 21 | 173/99 | + | + | O26:H− | This study |

| 22 | 209/99 | − | + | O113:H18 | This study |

| 23 | 240/99 | − | + | O30:HNT | This study |

| 24 | 285/99 | + | − | O145:HNT | This study |

| 25 | 328/99 | − | − | O16:H6 | This study |

| 26 | 431/99 | − | − | O157:H7 | This study |

| 27 | 497/99 | + | − | O103:H4 | This study |

| 28 | 516/99 | + | − | ONT:H− | This study |

| 29 | 575/99 | − | + | O157:H− | This study |

| 30 | 576/99 | − | + | O157:H− | This study |

| 31 | 594/99 | + | − | ONT:H− | This study |

| 32 | 649/99 | − | + | ONT:H9 | This study |

| 33 | 680/99 | + | + | O157:H− | This study |

| 34 | 713/99 | + | − | O115:H10 | This study |

| 35 | 720/99 | + | − | O111:H− | This study |

| 36 | 789/99 | + | − | O103:HNT | This study |

| 37 | 791/99 | + | − | O91:HNT | This study |

| 38 | 809/99 | + | − | O103:H2 | This study |

| 39 | 826/99 | + | − | O82:H− | This study |

| 40 | 827/99 | − | + | O157:H− | This study |

| 41 | 834/99 | + | − | O103:H2 | This study |

| 42 | EDL 933 | + | + | O157:H7 | 15 |

| 43 | EDL 973 | + | − | O157:H7 | 15 |

| 44 | 86-24 | − | + | O157:H7 | 5 |

| 45 | 126814/97 | − | + | O26:H11 | This study |

| 46 | ED 42 | − | + | O101:H− | 4 |

| 47 | ED 43 | − | + | O101:H14 | 4 |

| 48 | ED 68 | − | + | O101:H14 | 4 |

PCR primers and probes.

Primers (MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany) and probes (TIB MOLBIOL, Berlin, Germany) (Table 3) were designed by using the alignments of 27 previously published stx1 and stx2 sequences (Table 3). FRET hybridization probes for detection of stxA1 and stxA2 were marked with LightCycler Red 705 and LightCycler Red 640 as acceptor dyes, respectively. The stxA1-specific probes matched 100% to all sequences aligned, while the stxA2-specific probes had two mismatches with all stx2e sequences.

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide sequences of primers and probes used in the study

| Primer or probe | Name | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Function | Positionab | Tmc (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primers | |||||

| stx1 | StxA1 598 | AGT CGT ACG GGG ATG CAG ATA AAT | Sense | 598–621 | 56.9 |

| StxA1 1015 | CCG GAC ACA TAG AAG GAA ACT CAT | Antisense | 1015–992 | 55.3 | |

| stx2 | StxA2 679 | TTC CGG AAT GCA AAT CAG TC | Sense | 679–698 | 52.5 |

| StxA2 942 | CGA TAC TCC GGA AGC ACA TTG | Antisense | 942–922 | 54.6 | |

| Probes | |||||

| stx1 | StxA1 FL 724 | CTG TCA CAG TAA CAA ACC GTA ACA TCG CTC-X | FL probe | 724–695 | 65.5 |

| StxA1 LC 693 R7 | LC-TGC CAC AGA CTG CGT CAG TGA GGT-ph | Red 705 probe | 693–670 | 67.5 | |

| stx2 | StxA2 FL 769 | MAG AGC AGT TCT GCG TTT TGT CAC TGT CA-X | FL probe | 769–797 | 65.0 |

| StxA2 LC 799 R6 | LC-AGC AGA AGC CTT ACG CTT CAG GC-ph | Red 640 probe | 799–821 | 63.3 |

Sequence M19473 (7) is used as reference for the nucleotide positions of stx1-specific primers and probes; X07865 (6) serves as reference sequence with all stx2-specific oligonucleotides.

Sequences used for alignment: eight stx1 sequences (accession nos. M19473, M23980, M16625, M17358, Z36899, Z36900, Z36901, AJ32761), three stx2 sequences (accession nos. X07865, E03959, E03962), nine stx2v sequences (accession nos. AF043627, L11079, M59432, X65949, Z37725, X61283, X67514, Z50754, AJ272135), and seven stx2e sequences (accession nos. M21534, M36727, U72191, X81415, X81416, X81417, X81418).

Tm, melting temperature.

PCR.

The amplification program included an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 120 s and 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 s, annealing at 55°C for 5 s (reached with a touchdown from 60°C over the course of the first five cycles), and extension at 72°C for 20 s. The temperature transition rate was 20°C/s. A melting curve analysis was performed after the last amplification cycle. Additionally, all amplification products were visualized by conventional gel electrophoresis. The 20-μl sample volume in a glass capillary contained the following: for all single PCR experiments, 2 μl of 10× LightCycler DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), 10 pM each primer, 4 mM MgCl2, and 10 μl of DNA; for all multiplex experiments, 2 μl of 10× LightCycler DNA Master for hybridization probes (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), concentrations of primers and MgCl2 identical to those described above, 3 pM each hybridization probe, and 8 μl of DNA.

PCR optimization and sensitivity.

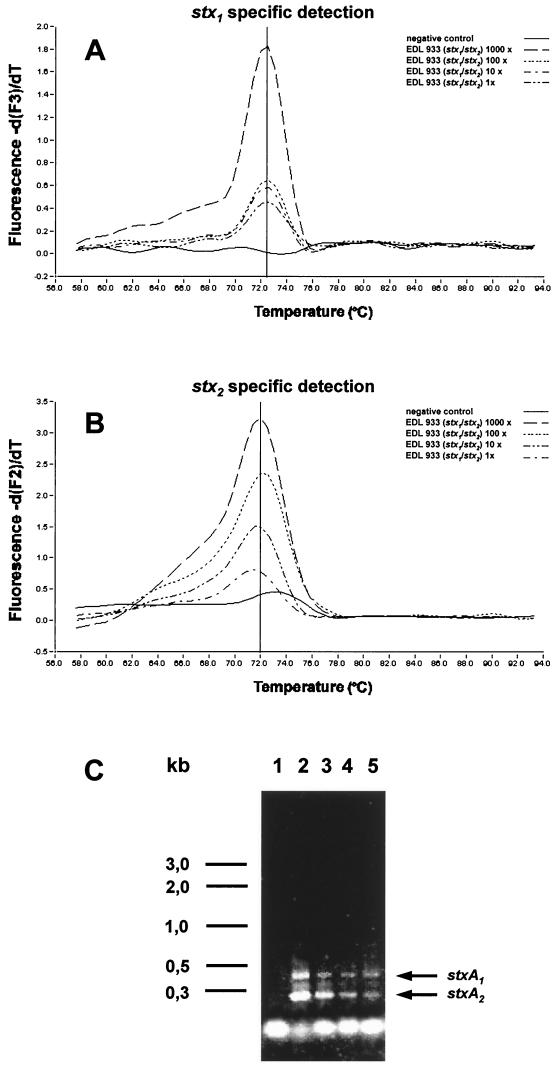

The PCR protocol was optimized in two steps. First, the stxA1- and stxA2-specific primer pairs were both evaluated with single PCRs in SYBR Green I format. At an MgCl2 concentration of 4 mM we were able to detect a single copy of either stx gene of EHEC EDL 933, which corresponds to a sensitivity of one organism per sample. In the second step we used both sets of primers together with the stxA1- and stxA2-specific hybridization probes in a multiplex assay. Without changing the MgCl2 concentration we could still maintain a sensitivity of one organism per sample, as shown by a 10-fold dilution series from 1,000 to 1 genome equivalents of our reference strain (Fig. 1). With the hybridization probes, the PCR products were found to reproducibly yield melting peaks at 72°C for both stxA1 and stxA2 (Fig. 1). In the multiplex application, none of the 37 Stx-negative strains tested positive, while PCR data obtained for all STEC isolates with known genotypes (Table 2) corresponded without exception to the results from the pretesting.

FIG. 1.

Multiplex amplification of a dilution series of the Stx double producer EHEC EDL 933 for evaluation of sensitivity of the PCR protocol. (A) stx1-specific signal in the −d(F)/dT plot of the third channel (LightCycler Red 705); (B) stx2-specific signal in the −d(F)/dT plot of the second channel (LightCycler Red 640) (the melting points of both stx genes were 72°C); (C) submarine agarose gel of the PCR products. A negative control (lane 1) and 10-fold dilution series of genome equivalents of EHEC EDL 933 (lanes 2 to 5) at 1,000 copies (lane 2), 100 copies (lane 3), 10 copies (lane 4), and 1 copy (lane 5) were tested. Both PCR fragments had the expected size of 418 bp for stxA1 and 246 bp for stxA2, calculated from the nucleotide positions of their amplification primers. A 1-kb DNA ladder was used as the DNA size marker (left side of the panel).

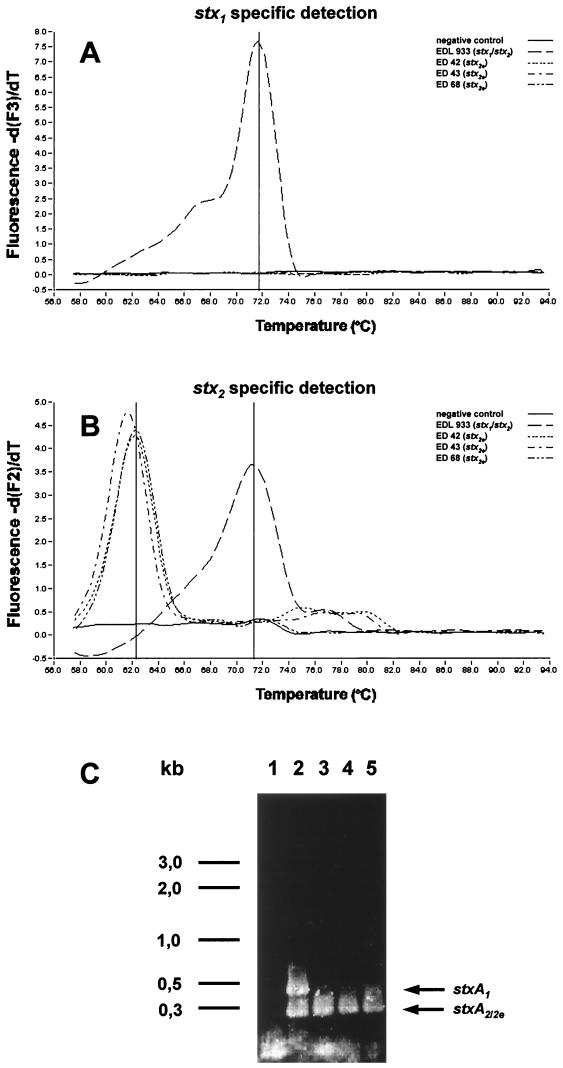

Discrimination between stx2/2v and stx2e alleles.

The PCR products of three EHEC isolates, isolates ED 42, ED 43, and ED 68 (Table 2), harboring the gene of the pig edema disease toxin (4), yielded melting peaks at only 62.5°C in the second channel (Fig. 2), where the stx2-specific fluorescence signal is recorded. This temperature downshift resulted from the mispriming of the stxA2-specific hybridization probes upon binding to stx2e target sequences as described above. The lowered melting points could easily be distinguished from the stx2/2v peaks at 72°C in the same channel (Fig. 2), making the stx2e genes clearly identifiable in this assay without further sequencing.

FIG. 2.

Multiplex PCR of EHEC EDL 933 and three strains harboring stx2e, the gene of the pig edema disease toxin. (A) stx1-specific signal in the −d(F)/dT plot of the third channel (LightCycler Red 705); (B) stx2 specific signal in the −d(F)/dT plot of the second channel (LightCycler Red 640). (the melting points were 72°C for stx1 and stx2 and 62.5°C for stx2e); (C) agarose gel of the respective PCR products. A negative control (lane 1) and EHEC EDL 933 (lane 2), EHEC ED 42 (lane 3), EHEC ED 43 (lane 4), and EHEC ED 68 (lane 5) were tested. The size of the three stxA2e amplicons was 246 bp, as expected. The positions of a 1-kb DNA ladder are indicated along the left side of the panel.

Our LightCycler-based multiplex PCR assay for detection of STEC delivers results quickly and makes it easy to repeat experiments that have failed. That is what will make this LightCycler application especially attractive for areas of work with a large number of samples, such as stool diagnostics in clinical microbiology or food safety surveillance. Furthermore, the protocol that we developed not only can detect stx2e but also can discriminate it from stx2/2v alleles by means of a melting curve analysis, a feature potentially interesting for epidemiology.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Bitter-Suermann for continuous support and encouragement. We thank K. Drexler, S. Kafert, and N. Kornprobst for helpful discussions. We also thank A. Donohue-Rolfe, from whose laboratory we received EHEC isolates 86-24, EDL 933, and EDL 973, and S. Franke and R. Bauerfeind, who gave us strains ED 42, ED 43, and ED 68.

This study was financially supported by the Zentrum für Zelltherapie/Cytonet, Hannover, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brian M J, Frosolono M, Murray B E, Miranda A, Lopez E L, Gomez H F, Cleary T G. Polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infection and hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1801–1806. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1801-1806.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle M P. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and its significance in foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;12:289–301. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90143-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fagan P K, Hornitzky M A, Bettelheim K A, Djordjevic S P. Detection of shiga-like toxin (stx1 and stx2), intimin (eaeA), and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) hemolysin (EHEC-hlyA) genes in animal feces by multiplex PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:868–872. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.868-872.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franke S, Harmsen D, Caprioli A, Pierard D, Wieler L H, Karch H. Clonal relatedness of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli O101 strains of human and porcine origin. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3174–3178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3174-3178.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin P M, Ostroff S M, Tauxe R V, Greene K D, Wells J G, Lewis J H, Blake P A. Illnesses associated with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. A broad clinical spectrum. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:705–712. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-9-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson M P, Neill R J, O'Brien A D, Holmes R K, Newland J W. Nucleotide sequence analysis and comparison of the structural genes for Shiga-like toxin I and Shiga-like toxin II encoded by bacteriophages from Escherichia coli 933. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;44:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson M P, Newland J W, Holmes R K, O'Brien A D. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the structural genes for Shiga-like toxin I encoded by bacteriophage 933J from Escherichia coli. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karch H, Meyer T. Single primer pair for amplifying segments of distinct Shiga-like-toxin genes by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2751–2757. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2751-2757.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livak K J, Flood S J, Marmaro J, Giusti W, Deetz K. Oligonucleotides with fluorescent dyes at opposite ends provide a quenched probe system useful for detecting PCR product and nucleic acid hybridization. PCR Methods Appl. 1995;4:357–362. doi: 10.1101/gr.4.6.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marques L R, Peiris J S, Cryz S J, O'Brien A D. Escherichia coli strains isolated from pigs with edema disease produce a variant of Shiga-like toxin II. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;44:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mead P S, Griffin P M. Escherichia coli O157:H7. Lancet. 1998;352:1207–1212. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paton A W, Paton J C, Goldwater P N, Manning P A. Direct detection of Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin genes in primary fecal cultures by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3063–3067. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.3063-3067.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paton A W, Ratcliff R M, Doyle R M, Seymour M J, Davos D, Lanser J A, Paton J C. Molecular microbiological investigation of an outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome caused by dry fermented sausage contaminated with Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1622–1627. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1622-1627.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paton J C, Paton A W. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:450–479. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley L W, Remis R S, Helgerson S D, McGee H B, Wells J G, Davis B R, Hebert R J, Olcott E S, Johnson L M, Hargrett N T, Blake P A, Cohen M L. Hemorrhagic colitis associated with a rare Escherichia coli serotype. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:681–685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303243081203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skeidsvoll J, Ueland P M. Analysis of double-stranded DNA by capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detection using the monomeric dye SYBR Green I. Anal Biochem. 1995;231:359–365. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.9986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wittwer C T, Ririe K M, Andrew R V, David D A, Gundry R A, Balis U J. The LightCycler: a microvolume multisample fluorimeter with rapid temperature control. BioTechniques. 1997;22:176–181. doi: 10.2144/97221pf02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yukioka H, Kurita S. Escherichia coli O157 infection disaster in Japan, 1996. Eur J Emerg Med. 1997;4:165. doi: 10.1097/00063110-199709000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]