Abstract

Sequence analysis at the 35-fold-repetitive B1 locus identified three restriction sites capable of discriminating type I (mouse-virulent) from type II or III (mouse-avirulent) strains of Toxoplasma gondii. B1 PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of 8 type I, 17 type II, and 8 type III strains confirms the specificity of the assay. It should now be possible to ask whether strain genotype affects the severity and type of clinical disease in humans.

Toxoplasmosis is a potentially fatal disease of the developing human fetus and immunocompromised (e.g., AIDS and transplant) patients and can cause severe ocular disease in otherwise healthy individuals (7, 10, 14). Recent population genetic studies have identified a remarkably limited number of Toxoplasma gondii genotypes in nature, the vast majority of which fall into one of only three distinct lineages (9). One of these lineages (type I) is highly virulent in mice (13). It is unclear whether a similar situation exists for human infection as inadequate data exist correlating the genotype of Toxoplasma with the symptoms and severity of disease that results. Studies to date have been hampered by the lack of a serological test to discriminate between strains and by insufficient parasite numbers in biopsy material for direct PCR amplification of single-copy polymorphic loci. Nevertheless, preliminary indications are that type II strains predominate in infections of immunocompromised patients and that type I strains are relatively overrepresented in congenital infections (8). More recently, we have uncovered a striking bias toward type I or type I-like strains associated with severe and/or atypical ocular toxoplasmosis in infected immunocompetent adults (M. E. Grigg, J. Ganatra, J. C. Boothroyd, and T. P. Margolis, submitted for publication).

B1 is a tandemly arrayed 35-fold-repetitive gene routinely used for the highly specific and sensitive PCR detection of Toxoplasma gondii present in clinical specimens (3–6, 11, 12). Given its widespread use for diagnosis of T. gondii infection, we explored whether this locus could be used for genotyping the strains responsible for causing disease in infected individuals. We envisaged that if concerted evolution operates on the B1 locus, all 35 B1 genes should be highly conserved within a given strain, yet perhaps differ between strains, and thus make it possible to determine strain type in raw isolates where parasite DNA exists in vanishing amounts.

PCR primers were designed to amplify a large portion (∼2 kb) of each B1 gene repeat from archetypal type I, II, and III lineage strains to maximize our chances of identifying relevant polymorphisms that encode diagnostic restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs). For this study, we used the following well-characterized strains: RH (type I, mouse virulent), Prugniaud or PDS (type II, mouse avirulent), and CEP (type III, mouse avirulent). PCR amplification was carried out on 104 parasite equivalents of either purified genomic DNA (prepared as described in reference 1) or cell lysate (prepared as described in reference 13). Each PCR utilized 5 μl of PCR Buffer (10× Perkin-Elmer PCR buffer containing 15 mM MgCl2), 0.1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, 10 pmol of each primer, and 1.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. Each of the 30 cycles consisted of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s. PCR amplification was performed using an automated thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer 140). PCR products were visualized using an ethidium-stained 0.8% agarose gel.

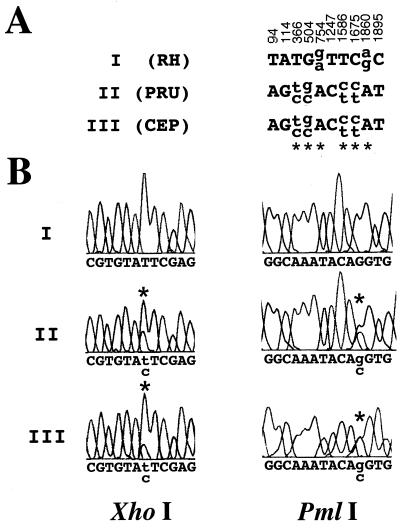

Sequence analysis was performed by the Stanford PAN facility on gel-purified DNA (UltraClean 15 DNA Purification kit; MoBio Labs) from the PCR-amplified material to ensure that the sequence obtained accurately reflects the nucleotide(s) present in most or all 35 B1 genes. Comparison of the DNA sequence for B1-amplified material from each of the three strains identifies only 10 polymorphic sites. This confirms that there exists remarkable sequence conservation (∼99.5%) regardless of the archetypal strain examined among all B1 genes (Fig. 1A). All 10 polymorphic sites distinguish the virulent RH strain from the two avirulent strains, which gave the same sequence. At four of the polymorphic sites, a single, homogeneous nucleotide substitution is present in the RH repeats compared with the other two. For the remaining six sites, demarcated by an asterisk in Fig. 1A, a substantial and reproducible number of the B1 gene repeats in a given strain possess one or the other of two nucleotides. Note that the relative ratio of nucleotides at these two-nucleotide sites varies somewhat between amplifications, as evidenced by multiple sequencing reads, but that there is always a substantial representation of both (Fig. 1B; data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Sequence analysis at B1. (A) Polymorphic sites that exist between the three major lineages are represented. B1 sequences were obtained from three archetypal type I, II, and III strains (RH, Prugniaud, and CEP, respectively). The numerical positions annotated refer to the numbered sites in the published sequence (GenBank accession no. AF179871). Sites demarcated by an asterisk indicate polymorphic sites at which two nucleotides are observed at significant levels (the upper letter represents the more abundant nucleotide) in the PCR-amplified material. Nucleotide positions 366, 504, and 1586 fall within potential restriction sites for XhoI (C/TCGAG), PmlI (CAC/GTG), and XcmI (CCAN5/N4TGG), respectively, in the type II and III sequences. PCR primers used for amplification and sequencing were as follows: S1, 5′-CGACAGAAAGGGAGCAAGAG (positions 10 to 29); S2, 5′-CCGGGCAAGAAAATGAGAT (positions 1005 to 1023); AS1, 5′-ACGCTGTGTCTCCTCTAGGC (positions 1043 to 1024); and AS2, 5′-CATGGTTTGCACTTTTGTGG (positions 1991 to 1972). Parenthetical numbers indicate GenBank nucleotide positions. (B) DNA sequence electropherogram of the B1 PCR-amplified population for RH (type I), Prugniaud (type II), and CEP (type III). Dye peaks shown bracket the polymorphic XhoI and PmlI restriction endonuclease sites. At positions 366 and 504, denoted by the asterisks, two nucleotide peaks are clearly present only in the sequences from the avirulent strains.

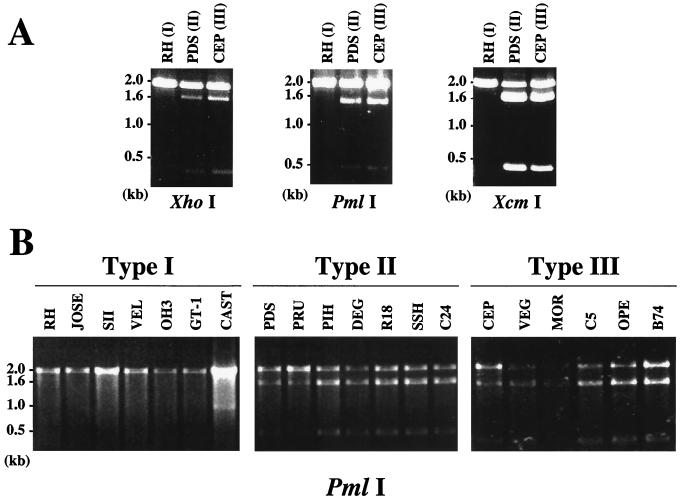

Three of the six two-nucleotide sites fall within potential restriction sites for XhoI, PmlI, and XcmI, at positions 366, 504, and 1586, respectively (Fig. 1A). RFLP analysis of three independent PCR amplifications confirm that all three enzymes consistently and reproducibly digest some but not all B1 amplification products from the two avirulent strains, whereas no digestion is observed for the virulent RH strain PCR product (Fig. 2A). To ascertain whether the diagnostic restriction sites determined by sequencing are in fact universal among avirulent lineages, seven type I, seven type II, and six type III strains were subjected to B1 PCR-RFLP analysis. These 20 strains are all of independent origin and were previously typed by extensive analysis at multiple loci (9, 13). For all three polymorphic restriction sites, digests identify the same RFLP pattern seen for archetypal strains (i.e., no digestion of virulent but partial digestion of all avirulent strains amplified), thus confirming a highly specific assay capable of discriminating avirulent from virulent strains of Toxoplasma (Fig. 2B [PmlI]; data not shown [XhoI and XcmI]). Although some variation in the ratio of cut to uncut DNA exists among avirulent strains, because of the nature of PCR, we do not feel confident that it is possible to discriminate between avirulent strains within the same lineage based on the ratio observed (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

B1 PCR-RFLP analysis distinguishes virulent from avirulent strains. (A) XhoI, PmlI, and XcmI digestion of B1 PCR-amplified DNA from RH (I), PDS (II), and CEP (III). (B) PmlI digestion of B1 PCR-amplified product from parasite genomic DNA preparations of seven type I, seven type II, and six type III strains was carried out. For more detailed information on strains amplified, see references 9 and 13.

Given the highly limited population structure of Toxoplasma, in which three distinct clonal lineages comprise >94% of the strains thus far identified, single-locus B1 genotyping of clinical samples should correctly distinguish virulent type I strains from avirulent strains with a high degree of confidence. The existence of multiple diagnostic restriction sites at B1 will likewise increase the confidence for the specific diagnosis of which archetypal strain type is present.

To permit greater sensitivity and rapid detection of parasite material for genotyping of T. gondii in clinical samples, we developed a set of nested primers optimized to PCR amplify B1 DNA around the XhoI and PmlI restriction sites. PCR primers used for amplification are as follows: Pml/S1, 5′-TGTTCTGTCCTATCGCAACG (positions 128 to 147); Pml/S2, 5′-TCTTCCCAGACGTGGATTTC (positions 152 to 171); Pml/AS1, 5′-ACGGATGCAGTTCCTTTCTG (positions 707 to 688); and Pml/AS2, 5′-CTCGACAATACGCTGCTTGA (positions 682 to 663). Parenthetical numbers indicate GenBank nucleotide positions. Using this PCR approach, we have examined 24 additional clinical samples, and in all cases involving clear type I, II, or III strains (determined by multilocus PCR-RFLP analysis), the B1 assay correctly distinguishes type I virulent from type II or III avirulent strains (data not shown). In the very rare strains that are not type I, II, or III, the B1 RFLP pattern was either type I-like (not cut by XhoI nor PmlI) or type II/III-like (cut by XhoI and PmlI), or, for one, there was a novel pattern (cut by PmlI but not XhoI) (data not shown).

In conclusion, the B1 assay described should permit the rapid and sensitive detection of parasite material in clinical samples for routine genotyping of strains from patients infected with T. gondii. As with any single-locus genotyping strategy, however, the rare, atypical strains in the population structure of T. gondii (reported to occur at ∼5% frequency [9]) will not be correctly assigned by this methodology. The recent success of amplifying B1 from the peripheral blood of individuals suffering from acute disease should likewise obviate the need for recovering parasite material by more invasive biopsy and/or make it possible to determine the genotype in biopsy material when the amount of parasite DNA is too small to detect polymorphic single-copy loci (2). Moreover, prenatal diagnosis of congenital Toxoplasma infection by B1 PCR amplification from amniotic fluid is a routinely performed procedure (6). Our assay should provide the diagnostic means to readily determine whether T. gondii infection is caused by a mouse-virulent or -avirulent strain and whether strain type influences disease outcome in humans. Such information will allow the aggressiveness of the treatment to be matched to the predicted severity of the disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Sibley and Dan Howe for providing some of the parasite lysates used in this study. We are grateful to the Jules Stein Eye Institute for equipment support and Gary Holland in particular for his enthusiastic encouragement.

This work was supported by grants from the Alameda County District Attorney's Office (Food Safety Initiative) and from the National Institutes of Health (AI21423 and AI41014).

REFERENCES

- 1.Black W M, Boothroyd J C. Development of a stable episomal shuttle vector for Toxoplasma gondii. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3972–3979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bou G, Figueroa M S, Marti-Belda P, Navas E, Guerrero A. Value of PCR for detection of Toxoplasma gondii in aqueous humor and blood samples from immunocompetent patients with ocular toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3465–3468. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3465-3468.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burg J L, Grover C M, Pouletty P, Boothroyd J C. Direct and sensitive detection of a pathogenic protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii, by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1787–1792. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.8.1787-1792.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danise A, Cinque P, Vergani S, Candino M, Racca S, De Bona A, Novati R, Castagna A, Lazzarin A. Use of polymerase chain reaction assays of aqueous humor in the differential diagnosis of retinitis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1100–1106. doi: 10.1086/513625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grover C M, Thulliez P, Remington J S, Boothroyd J C. Rapid prenatal diagnosis of congenital Toxoplasma infection by using polymerase chain reaction and amniotic fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2297–2301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.10.2297-2301.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hohlfeld P, Daffos F, Costa J M, Thulliez P, Forestier F, Vidaud M. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis with a polymerase-chain-reaction test on amniotic fluid. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:695–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409153311102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holland G N. Reconsidering the pathogenesis of ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:502–505. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howe D K, Honore S, Derouin F, Sibley L D. Determination of genotypes of Toxoplasma gondii strains isolated from patients with toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1411–1414. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1411-1414.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howe D K, Sibley L D. Toxoplasma gondii comprises three clonal lineages: correlation of parasite genotype with human disease. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1561–1566. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter C A, Remington J S. Immunopathogenesis of toxoplasmic encephalitis. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1057–1067. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.5.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones C D, Okhravi N, Adamson P, Tasker S, Lightman S. Comparison of PCR detection methods for B1, P30, and 18S rDNA genes of T. gondii in aqueous humor. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:634–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montoya J G, Parmley S, Liesenfeld O, Jaffe G J, Remington J S. Use of the polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1554–1563. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibley L D, Boothroyd J C. Virulent strains of Toxoplasma gondii comprise a single clonal lineage. Nature. 1992;359:82–85. doi: 10.1038/359082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong S Y, Remington J S. Toxoplasmosis in pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:853–861. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]