Abstract

This review aims to provide a functional, metabolic view of the pathogenesis of benign thyroid disease. Here, we summarize the features of our previous publications on the “WOMED model of benign thyroid disease”. As of 2021, the current state of art indicates that the basic alteration in benign thyroid disease is a metabolic switch to glycolysis, which can be recognized using 3D-power Doppler ultrasound. A specific perfusion pattern showing enlarged vessels can be found using this technology. This switch originates from an altered function of Complex I due to acquired coenzyme Q10 deficiency, which leads to a glycolytic state of metabolism together with increased angiogenesis. Implementing a combined supplementation strategy that includes magnesium, selenium, and CoQ10, the morphological and perfusion changes of the thyroid can be reverted, i.e., the metabolic state returns to oxidative phosphorylation. Normalization of iron levels when ferritin is lower than 50 ng/mL is also imperative. We propose that a modern investigation of probable thyroid disease requires the use of 3D-power Doppler sonography to recognize the true metabolic situation of the gland. Blood levels of magnesium, selenium, CoQ10, and ferritin should be monitored. Thyroid function tests are complementary so that hypo- or hyperthyroidism can be recognized. Single TSH determinations do not reflect the glycolytic state.

Keywords: thyroid, magnesium, selenium, coenzyme Q10, ferritin, mitochondria, oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis, hypoxia

1. Preamble

The practice of good clinical medicine practice requires the exact recognition of fundamental biochemical processes that cause disease. Acquiring this knowledge will allow practitioners to provide an adequate treatment that will modify the key processes of pathogenesis. This goal setting corresponds to concepts brought by Stetenga looking at medical interventions and their effectiveness [1]. A key concept from this publication states the following: “To be effective, a medical intervention must improve one’s health by targeting a disease”. This goal coincides with the principles of effectiveness and efficiency pointed out by Archie Cochrane [2].

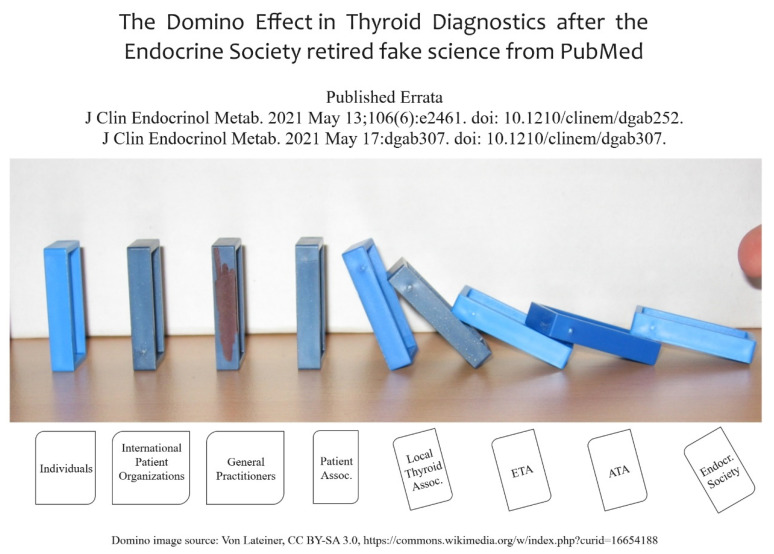

Following the principles related to evidence of research findings and clinical practice [3], a series of guidelines for clinical practice commenced appearing in the 1990s [4]. The Institute of Medicine Committee included the following statement on validity: “VALIDITY: Practice guidelines are valid if, when followed, they lead to the health and cost outcomes projected for them” (p. 10, [4]). The field of clinical practice and thyroid diseases has been shattered in 2021 by an unprecedented action taken by the Endocrine Society. On 26 February 2021, i.e., fourteen years after the publication by Abalovich, Amino, Barbour, Cobin, De Groot, Glinoer, Mandel, and Stagnaro-Green (PMID 17948378), the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism has retired the guideline [5]. The same happened to the 2012 update of the guideline [6] which was written by De Groot, Abalovich, Alexander, Amino, Barbour, Cobin, Eastman, Lazarus, Luton, Mandel, Mestman, Rovet, and Sullivan (PMID 22869843). This action will certainly have a large impact on medical practice since many publications were built upon these misconceptions (Figure 1). It is quite unfortunate that the Endocrine Society did not give precise information about this critical procedure. We have chosen to use the PMID identifiers to avoid any unnecessary citation of these discredited articles.

Figure 1.

Domino effect of retiring clinical practice guidelines affecting thyroid societies and individuals.

“Science is built of facts the way a house is built of bricks: but an accumulation of facts is no more science than a pile of bricks is a house.”

Henri Poincaré (1854–1912)

Lateiner, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16654188 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

In the following sections, we will summarize our biochemical function-related model of acquired thyroid disease, which aims at restoration of the thyroid, thus restoring health.

2. Introduction

This publication aims to demonstrate concisely our understanding of the metabolic pathogenesis of thyroid disease and to describe the biochemical interventions needed for a successful treatment. Within the context of evidence in medicine, Chambless and Hollon presented the following statement: “…efficacy must be demonstrated in controlled research in which it is reasonable to conclude that benefits observed are due to the effects of the treatment and not to chance or confounding factors…” [7]. Following this principle, we will emphasize the importance of 3D-power Doppler ultrasound examination of the thyroid for the evaluation of the morphology and perfusion of the gland. This methodology has allowed us to recognize that increased thyroid perfusion can be seen in hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, during pregnancy, postpartum, or post-COVID-19 infections. The main biochemical correlate of this situation is coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) deficiency. Based on recent experimental studies by Liparulo et al. concerning the effect of CoQ10 synthesis inhibition on the metabolic switch to glycolysis [8], we can now interpret our sonography findings as being indicative of glycolysis—and hypoxia—in the thyroid. We have been able to confirm this hypothesis through the use of diagnostic imaging using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (Figure 6 in [9]).

Besides CoQ10 deficiency, thyroid disease patients are also deficient in magnesium, selenium, and iron. When these deficiencies are corrected by supplementing the missing elements, we have documented reconstitution of thyroid morphology and perfusion [10]. By this, our approach coincides with the requirements for measuring effectiveness advanced by Stetenga asking for the use of a good measuring instrument together with an adequate measure of outcome [11].

Ultrasound and 3D-perfusion evaluations of the thyroid have never been included in clinical practice guidelines coming from expert consensus meetings. The same applies to laboratory determinations of magnesium, selenium, CoQ10, and iron. These conceptual limitations do not allow us to compare our results with the medical literature dedicated to thyroid diseases.

In the following sections, we will proceed to delineate our clinical practice procedure for patients with thyroid disease.

3. The Clinical Approach

Over two and a half decades, we have conducted consecutive observational studies, sequentially adding elements to the concepts of an acquired mitochondrial disorder and altered function of the endoplasmic reticulum referring to protein repair. Our clinical work has also dealt with the topics of thyroid function and female fertility [9,10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Every patient referred to an examination of the thyroid should go through detailed clinical history taking and ultrasound examination that includes 3D-power Doppler evaluation (Table 1).

Table 1.

The clinical approach to cases where thyroid dysfunction is suspected.

| Parameter | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Clinical history | Has thyroid disease been suspected before? What were the symptoms? |

| Was the previous diagnosis done using “fake” reference values for TSH? | |

| How was the diagnostic approach? Are there any previous ultrasound examinations? What did the power Doppler pattern of thyroid perfusion show? | |

| Are the initial symptoms still present? | |

| Are there any residual symptoms? Fatigue? | |

| Thyroid morphology | Normal structure |

| Inhomogeneous pattern with some areas presenting decreased echogenicity | |

| Pronounced inhomogeneous pattern | |

| Loss of echogenicity, i.e., thyroid pattern is the same as that of muscle | |

| Pronounced changes with fibrosis | |

| Thyroid perfusion | Normal |

| Slight increase with a point-like pattern—suggests magnesium deficiency | |

| Moderate increase with a wire-like pattern—suggests CoQ10 deficiency | |

| Very intense hyper-perfusion—suggests a severe combined deficiency condition | |

| Basic laboratory parameters | Magnesium, ferritin |

| CK and NT-proBNP | |

| Selenium and CoQ10 | |

| Thyroid function parameters | fT3, fT4, TSH. Thyroid antibodies. |

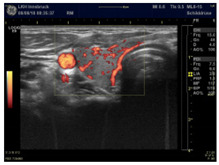

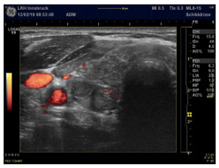

4. Interpretation of Thyroid Ultrasound and 3D-Power Doppler Perfusion

The classical description of chronic thyroid disease was made by Hashimoto in 1912 [29]. In Table 2, we compare the findings of Hashimoto with the relevant biochemical and sonography parameters involved in thyroid disease. The original text in German used by Hashimoto is included in the heading of the corresponding columns.

Table 2.

Summary of the WOMED clinical approach to thyroiditis concerning the 3 main findings described by Hashimoto (in the original German description). The clinical validity of diagnostic procedures including power Doppler sonography is explained for every stage.

| “Eigenthümliche Art von Chronischer Entzündung” | “Wucherung des Gefässendothels” | “Fällt Selbst dem Schwunde Anheim” | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Inflammation | Enlarged Endothel | Destruction | |

| TSH | no | no | Elevated in hypothyroidism |

| Thyroid-Abs | Partial correlation | no | no |

| Ferritin | no | no | no |

| Magnesium | yes | yes | Partly |

| Coenzyme Q10 | yes | yes—relates to the dynamics of perfusion | No |

| Selenium | yes | no | Yes in fibrosis |

| Sonography | yes | yes | yes |

| Power Doppler Images |

|

|

|

| Condition | Magnesium def. pattern | CoQ10 def. pattern | Chronic fibrosis |

The findings of the sonography examinations can be translated into a descriptive table indicating which therapeutical approach is needed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Interpretation matrix of 3D-power Doppler Thyroid Sonography.

| Morphology | Perfusion | Magnesium | Coenzyme Q10 | Selenium |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | normal | |||

| Hypo echogenic homogeneous | fine granular | deficiency | ||

| Hypo echogenic inhomogeneous | thickened vessels | deficiency | deficiency | |

| Hypo echogenic inhomogeneous with fibrosis signs | moderately increased | probable | probable | deficiency |

| Very low echogenic | increased | deficiency | deficiency | deficiency |

| Very low echogenic with fibrosis signs | not increased = final stage | - | - | - |

Our clinical practice has brought us to the following prescription recommendations. Magnesium deficiency should be treated with pure magnesium citrate prepared as a magistral formulation at a dose of 3.5 to 4.0 g per day dissolved in water and taken during the day. The amount of elemental magnesium in the magnesium citrate salt corresponds to approximately 8% or 280 to 320 mg/day. The main theoretical advantage of this formulation lies in the ability of citrate to localize inflammation [30]. For the correction of selenium and CoQ10 deficiencies, we have relied on products from Pure Encapsulations® for 15 years and have obtained satisfactory results. The preparations used include selenomethionine (200 µg capsule) and CoQ10 (60 mg capsule). Supplementation begins with 1 capsule of selenomethionine and CoQ10 daily taken together at night during the first 2 weeks. Beginning on the 3rd week, the dose is reduced to only 3 capsules per week of each preparation taken on alternate days. Treatment costs amount to €220 per year or €0.66 per day. The efficacy of supplementation is controlled by laboratory determinations of these parameters. The target values to be reached through supplementation are >0.9 mmol/L for magnesium, >80 µg/dL for selenium, and >1200 µg/L for CoQ10. Ferritin levels should be >50 ng/mL. Power Doppler sonography examinations deliver in vivo information as to the levels of these nutrients and can also be used to monitor the supplementation therapy [10].

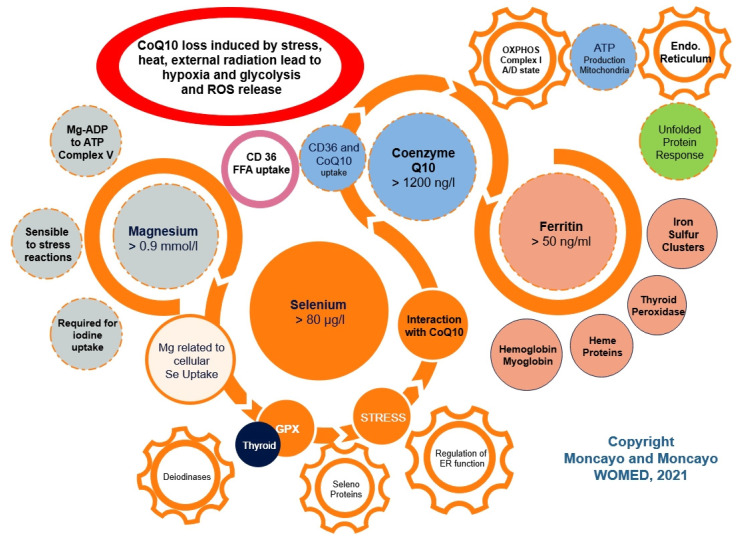

The essence of our concerning approach can be taken from the abstract of the publication by Kitano on Systems biology: “To understand biology at the system level, we must examine the structure and dynamics of cellular and organismal function, rather than the characteristics of isolated parts of a cell or organism” [31]. This biological point of view has been often forgotten by researchers who have evaluated magnesium, selenium, CoQ10, or iron as single, isolated parts of a complex organism in relation to thyroid or heart disease. Our simple model of mitochondrial complexity is shown in Figure 2. Mitochondrial integrity is essential for the prevention of reactive oxidative reactions.

Figure 2.

A simple model of mitochondrial complexity showing interactions of magnesium, selenium, CoQ10, and iron in relation to the function of mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum. The red oval depicts the critical situation of CoQ10 deficiency leading to glycolysis and ROS release.

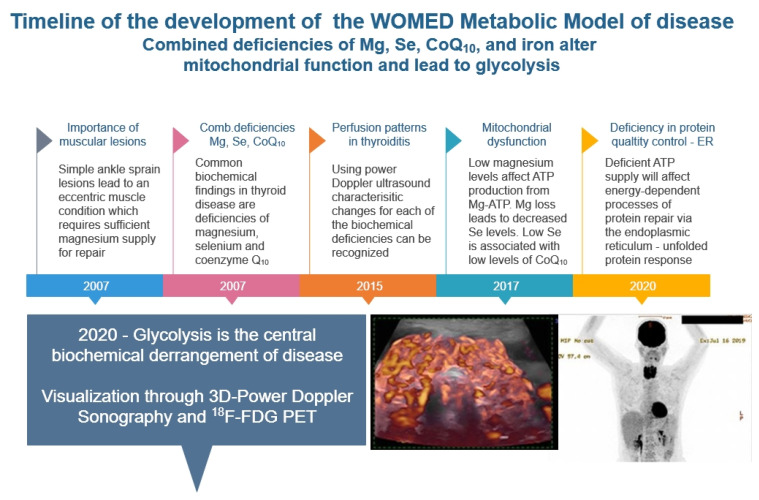

A timeline representation of our research leading to the detection of glycolysis—as a simile of hypoxia—is shown in Figure 3. The 18F-FDG PET image shows the concomitant glycolytic condition of the thyroid and heart.

Figure 3.

Timeline of our clinical investigations leading to the recognition of glycolysis as a key mechanism of disease affecting the thyroid and the heart.

5. Discussion

Several versions of “conventional” treatment approaches for thyroid disease have appeared in the past decades [32]. The predominant thesis of treatment adequacy contained in such guidelines has been to monitor TSH by laboratory determinations [33]. One gains the impression that thyroid treatment is exclusively oriented toward achieving specific TSH levels [34]. This practice philosophy ignores the investigation of basic pathogenetic processes present in the thyroid gland as well as clinical aspects and symptoms reported by patients. It is therefore not surprising to find several reports of treated patients who complain about residual symptoms (Table 4). This situation of dissatisfaction was the starting point for our studies in 2007.

Table 4.

Selected citations on failed thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

| Taylor (1970) [35] | “It may be the experience of many clinicians, as it has been ours, that a very small group of patients with hypothyroidism are not entirely well on thyroxine replacement alone.” |

| Walsh J.P. (2002) [36] | “… higher prevalence of symptoms consistent with hypothyroidism, such as impaired memory and clarity of thought, tiredness, weight gain, somatic pain and physical clumsiness.” |

| Saravanan (2002) [37] | “This community-based study is the first evidence to indicate that patients on thyroxine replacement even with a normal TSH display significant impairment in psychological well-being” |

| Weetman A.P. (2006) [38] | “The majority of patients who demand thyroid hormone treatment for multiple symptoms, despite normal thyroid function tests, have functional somatoform disorders.” |

| Okosieme (2016) [39] | “However, the management of patients with a sub-optimal clinical response remains challenging.” |

| McAnich and Bianco (2016) [40] | “The euthyroid yet symptomatic patient.” |

| Sheehan (2016) [41] | “Increasingly, when a physician informs a patient that their thyroid is not the cause of their symptoms, the patient is dissatisfied and even angry.” |

| Chaker (2017) [42] | “However, a substantial proportion of patients who reach biochemical treatment targets have persistent complaints.” |

| Stott (2017) [43] | “Levothyroxine provided no apparent benefits in older persons with subclinical hypothyroidism.” |

| Jonklaas (2017) [44] | “However, despite the successes in treating hypothyroidism, there are clearly diseases aspects of treating hypothyroidism that are not yet understood.” |

| Feller (2018) [45] | “These findings do not support the routine use of thyroid hormone therapy in adults with subclinical hypothyroidism.” |

| Yamamoto (2018) [46] | “… no evidence of benefit of levothyroxine therapy on obstetrical, neonatal, childhood IQ or neurodevelopmental outcomes.” |

| Mayor (2018) [47]—editorial comments on Feller | “The results, reported in JAMA, showed that thyroid hormone therapy (for 3–18 months) was associated with reducing the mean thyrotropin value into the normal reference range when compared with placebo (range 0.5–3.7 mIU/L v 4.6–14.7 mIU/L). But no improvement was found in thyroid related symptoms or quality of life.” |

| Hennessey (2018) [48] | “Persistent symptoms in patients who are biochemically euthyroid with LT4 monotherapy may be caused by several other conditions unrelated to thyroid function, and their cause should be aggressively investigated by the clinician.” |

| Peterson (2018) [49] | “While the study design does not provide a mechanistic explanation for this observation, future studies should investigate whether preference for DTE is related to triiodothyronine levels or other unidentified causes.” |

| Bekkering (2019) [50] | “For adults with SCH, thyroid hormones consistently demonstrate no clinically relevant benefits for quality of life or thyroid related symptoms, including depressive symptoms, fatigue |

| Taylor (2019) [51] | “… many patients have persistent concerns and dissatisfaction with their thyroid hormone replacement.” |

| de Montmollin 2020 [52] | ”In older adults with SCH and high symptom burden at baseline, L-thyroxine did not improve hypothyroid symptoms or tiredness compared with placebo.” |

| Samuels (2020) [53] | “Serum TSH levels are often measured in patients who report these nonspecific symptoms, and these patients are then treated for mild elevations in TSH that may be unrelated to the presenting symptoms.” |

| Mitchell (2021) [54] | “The main findings of this survey were a high rate of dissatisfaction with treatment and care. The form of thyroid hormone replacement taken did not correlate with treatment satisfaction.” |

| Perros (2021) [55] | “Interventions using L- T4 + L- T3 have been disappointing and are unlikely to unlock the persistent symptom enigma for the majority of patients.” |

| Borson-Chazot (2021) [56] | “In hypothyroidism, QoL appears to be influenced by a number of physiological, behavioral, cognitive and/or lifestyle factors that are not strictly related to thyroid hormone levels.” |

Our first study on nutrients and thyroid disease was focused on selenium, zinc, and vitamin C [19]. The identification of selenium deficiency as a common finding in benign and malignant diseases brought us back to look at the literature on this element. The starting point for investigations on the role of selenium in liver disease was set in 1957 by Schwarz and Foltz [57]. They described the beneficial effect of selenium in the context of dietary necrotic liver degeneration. In a fraction originally called Factor 3, they discovered that selenium was present. Two central observations on the relation between selenium and CoQ10 were done by Green et al. in 1961 [58] and by Hidiroglou in 1967 [59]. Administering selenium improved the tissue levels of CoQ10 in the experimental animals. A similar observation about this relation was published by Vadhanavikit and Ganther in 1993 [60]. This physiological aspect has not been considered in many studies that have chosen to study the effects of selenium or CoQ10 given as single agents to overcome putative oxidative changes. Another study speculated that the lowering of CoQ10 levels depended on the depressed GSH-Px activity that resulted from selenium deficiency [61].

In situations of selenium deficiency, mitochondrial structure and also the electron transport function were described as being altered [62]. A study on the distribution of selenium in mitochondria revealed that the highest concentration was found in the inter-membrane space, the inner membrane, and the matrix [63]. These studies delivered biochemical function concepts for our concept of acquired mitochondrial dysfunction.

The identification of glycolysis in the thyroid and the heart using diagnostic imaging methods [9] directed our attention to studies using similar methodology. The literature contains several descriptions of studies that have looked at diffuse thyroid uptake of 18F-FDG in PET imaging. Albano et al. recently reviewed this topic concerning thyroiditis [64]. Albano and many other authors found in the literature consider that the nature behind tracer uptake in the thyroid has remained unexplained. Although the professional background of the authors is nuclear medicine, their conclusions did not convey the real interpretation of images done with 18F-FDG PET, i.e., glycolysis. It is also noteworthy that an intense tracer uptake in the heart (Figure 2 in [64]) was left uncommented. Based on an ongoing literature evaluation being done by us, we believe that cardiac uptake also represents a situation of CoQ10 deficiency.

6. Conclusions

We consider that our model corresponds to epidemiological definitions when health problems are considered: “the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events in specific populations and the application of this study to control of health problems” [65]. TSH alone is not the central health problem and should not be taken as the ultimate minimalistic evaluation parameter of thyroid disease. We firmly believe that diagnostic imaging with advanced sonography techniques [9,20] for the investigation of thyroid disease has been a game-changer element that has broadened our view about the real disease pathogenesis. We propose that the examination procedure described by us in this manuscript can lead to a substantial improvement of clinical practice at times when multi-author practice recommendations have been dismantled [5,6].

Author Contributions

R.M. and H.M. contributed equally to the development of the pathogenesis model based on their clinical investigations. R.M. wrote the manuscript and created the figures. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was self-funded by WOMED, Innsbruck. No public funding was involved.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The cited publications of our previous research have appeared as open-source material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stegenga J. Effectiveness of medical interventions. Stud. Hist. Philos. Biol. Biomed. Sci. 2015;54:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.shpsc.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cochrane A.L. Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Health Services. 1st ed. Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust; Nuffield, UK: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haines A., Jones R. Implementing findings of research. BMJ. 1994;308:1488–1492. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6942.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine; Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines . Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. National Academies Press; Washington, DC, USA: 1990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrigendum to: “Management of Thyroid Dysfunction during Pregnancy and Postpartum: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline”. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021;106:e2844. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corrigendum to: “Management of Thyroid Dysfunction during Pregnancy and Postpartum: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline”. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021;106:e2461. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambless D.L., Hollon S.D. Defining empirically supported therapies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1998;66:7–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liparulo I., Bergamini C., Bortolus M., Calonghi N., Gasparre G., Kurelac I., Masin L., Rizzardi N., Rugolo M., Wang W., et al. Coenzyme Q biosynthesis inhibition induces HIF-1α stabilization and metabolic switch toward glycolysis. FEBS J. 2021;288:1956–1974. doi: 10.1111/febs.15561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moncayo R., Moncayo H., Reisenzahn J. Global view on the pathogenesis of benign thyroid disease based on historical, experimental, biochemical, and genetic data identifying the role of magnesium, selenium, coenzyme Q10 and iron in the context of the unfolded protein response and protein quality control of thyroglobulin. J. Transl. Genet. Genom. 2020;4:356–383. doi: 10.20517/jtgg.2020.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. Proof of concept of the WOMED model of benign thyroid disease: Restitution of thyroid morphology after correction of physical and psychological stressors and magnesium supplementation. BBA Clin. 2015;3:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stegenga J. Measuring effectiveness. Stud. Hist. Philos. Biol. Biomed. Sci. 2015;54:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.shpsc.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moncayo H.E., Moncayo R. Thyroid function and infertility. Hum. Reprod. 1997;12:2854–2856. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moncayo H.E., Penz-Koza A., Marth C., Gastl G., Herold M., Moncayo R. Vascular endothelial growth factor in serum and in the follicular fluid of patients undergoing hormonal stimulation for in-vitro fertilization. Hum. Reprod. 1998;13:3310–3314. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.12.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moncayo R., Moncayo H., Kapelari K. Nutritional treatment of incipient thyroid autoimmune disease. Influence of selenium supplementation on thyroid function and morphology in children and young adults. Clin. Nutr. 2005;24:530–531. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moncayo R., Moncayo H., Virgolini I. Reference values for thyrotropin. Thyroid. 2005;15:1204–1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moncayo H., Dapunt O., Moncayo R. Diagnostic accuracy of basal TSH determinations based on the intravenous TRH stimulation test: An evaluation of 2570 tests and comparison with the literature. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2007;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. A musculoskeletal model of low grade connective tissue inflammation in patients with thyroid associated ophthalmopathy (TAO): The WOMED concept of lateral tension and its general implications in disease. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2007;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapelari K., Kirchlechner C., Högler W., Schweitzer K., Virgolini I., Moncayo R. Pediatric reference intervals for thyroid hormone levels from birth to adulthood: A retrospective study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2008;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moncayo R., Kroiss A., Oberwinkler M., Karakolcu F., Starzinger M., Kapelari K., Talasz H., Moncayo H. The role of selenium, vitamin C, and zinc in benign thyroid diseases and of Se in malignant thyroid diseases: Low selenium levels are found in subacute and silent thyroiditis and in papillary and follicular carcinoma. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2008;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. Advanced 3D Sonography of the Thyroid: Focus on Vascularity. In: Thoirs K., editor. Sonography. 1st ed. Intech; Rijeka, Croatia: 2012. [(accessed on 19 December 2021)]. pp. 273–292. Available online: http://www.intechopen.com/articles/show/title/thyroid-sonography-in-3d-with-emphasis-on-perfusion. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. Exploring the aspect of psychosomatics in hypothyroidism: The WOMED model of body-mind interactions based on musculoskeletal changes, psychological stressors, and low levels of magnesium. Woman-Psychosom. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2014;1:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.woman.2014.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. The WOMED model of benign thyroid disease: Acquired magnesium deficiency due to physical and psychological stressors relates to dysfunction of oxidative phosphorylation. BBA Clin. 2015;3:44–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moncayo R., Ortner K. Multifactorial determinants of cognition—Thyroid function is not the only one. BBA Clin. 2015;3:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moncayo R., Zanon B., Heim K., Ortner K., Moncayo H. Thyroid function parameters in normal pregnancies in an iodine sufficient population. BBA Clin. 2015;3:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuefer S., Moncayo H., Moncayo R. The role of magnesium and thyroid function in early pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization (IVF): New aspects in endocrine physiology. BBA Clin. 2015;3:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. A post-publication analysis of the idealized upper reference value of 2.5 mIU/L for TSH: Time to support the thyroid axis with magnesium and iron especially in the setting of reproduction medicine. BBA Clin. 2017;7:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. Applying a systems approach to thyroid physiology: Looking at the whole with a mitochondrial perspective instead of just TSH values or why we should know more about mitochondria to understand metabolism. BBA Clin. 2017;7:127–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moncayo R., Matzak K. Therapiemöglichkeiten für Patienten mit Morbus Hashimoto. [(accessed on 19 December 2021)];Univers. Inn. 2019 20:52–57. Available online: https://www.medmedia.at/univ-innere-medizin/therapiemoeglichkeiten-fuer-patienten-mit-morbus-hashimoto/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto H. Zur Kenntniss der lymphomatösen Veränderung der Schilddrüse (Struma lymphomatosa) Arch. Klin. Chir. 1912;97:219–248. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ercan M.T., Aras T., Unlenen E., Unlu M., Unsal I.S., Hascelik Z. 99mTc-citrate versus 67Ga-citrate for the scintigraphic visualization of inflammatory lesions. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1993;20:881–887. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(93)90155-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitano H. Systems biology: A brief overview. Science. 2002;295:1662–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.1069492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biondi B. The normal TSH reference range: What has changed in the last decade? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98:3584–3587. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biondi B., Wartofsky L. Treatment with thyroid hormone. Endocr. Rev. 2014;35:433–512. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiovato L., Magri F., Carlé A. Hypothyroidism in Context: Where We’ve Been and Where We’re Going. Adv Ther. 2019;36:47–58. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01080-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor S., Kapur M., Adie R. Combined thyroxine and triiodothyronine for thyroid replacement therapy. Br. Med. J. 1970;2:270–271. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5704.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh J.P. Dissatisfaction with thyroxine therapy-could the patients be right? Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2002;2:717–722. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4892(02)00209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saravanan P., Chau W.F., Roberts N., Vedhara K., Greenwood R., Dayan C.M. Psychological well-being in patients on ‘adequate’ doses of l-thyroxine: Results of a large, controlled community-based questionnaire study. Clin. Endocrinol. 2002;57:577–585. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weetman A.P. Whose thyroid hormone replacement is it anyway? Clin. Endocrinol. 2006;64:231–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okosieme O., Gilbert J., Abraham P., Boelaert K., Dayan C., Gurnell M., Leese G., McCabe C., Perros P., Smith V., et al. Management of primary hypothyroidism: Statement by the British Thyroid Association Executive Committee. Clin. Endocrinol. 2016;84:799–808. doi: 10.1111/cen.12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McAninch E.A., Bianco A.C. The History and Future of Treatment of Hypothyroidism. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016;164:50–56. doi: 10.7326/M15-1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheehan M.T. Biochemical Testing of the Thyroid: TSH is the Best and, Oftentimes, Only Test Needed—A Review for Primary Care. Clin. Med. Res. 2016;14:83–92. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2016.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaker L., Bianco A.C., Jonklaas J., Peeters R.P. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 2017;390:1550–1562. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30703-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stott D.J., Rodondi N., Kearney P.M., Ford I., Westendorp R.G.J., Mooijaart S.P., Sattar N., Aubert C.E., Aujesky D., Bauer D.C., et al. Thyroid Hormone Therapy for Older Adults with Subclinical Hypothyroidism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:2534–2544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jonklaas J. Persistent hypothyroid symptoms in a patient with a normal thyroid stimulating hormone level. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2017;24:356–363. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feller M., Snel M., Moutzouri E., Bauer D.C., de Montmollin M., Aujesky D., Ford I., Gussekloo J., Kearney P.M., Mooijaart S., et al. Association of Thyroid Hormone Therapy With Quality of Life and Thyroid-Related Symptoms in Patients With Subclinical Hypothyroidism: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320:1349–1359. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamoto J.M., Benham J.L., Nerenberg K.A., Donovan L.E. Impact of levothyroxine therapy on obstetric, neonatal and childhood outcomes in women with subclinical hypothyroidism diagnosed in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022837. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayor S. Thyroid hormone therapy does not improve symptoms in subclinical hypothyroidism, review finds. BMJ. 2018;363:k4154. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hennessey J.V., Espaillat R. Current evidence for the treatment of hypothyroidism with levothyroxine/levotriiodothyronine combination therapy versus levothyroxine monotherapy. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2018;72:e13062. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peterson S.J., Cappola A.R., Castro M.R., Dayan C.M., Farwell A.P., Hennessey J.V., Kopp P.A., Ross D.S., Samuels M.H., Sawka A.M., et al. An Online Survey of Hypothyroid Patients Demonstrates Prominent Dissatisfaction. Thyroid. 2018;28:707–721. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bekkering G.E., Agoritsas T., Lytvyn L., Heen A.F., Feller M., Moutzouri E., Abdulazeem H., Aertgeerts B., Beecher D., Brito J.P., et al. Thyroid hormones treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism: A clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;365:l2006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor P., Bianco A.C. Urgent need for further research in subclinical hypothyroidism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019;15:503–504. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0239-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Montmollin M., Feller M., Beglinger S., McConnachie A., Aujesky D., Collet T.H., Ford I., Gussekloo J., Kearney P.M., McCarthy V.J.C., et al. L-Thyroxine Therapy for Older Adults With Subclinical Hypothyroidism and Hypothyroid Symptoms: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;172:709–716. doi: 10.7326/M19-3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samuels M.H. Dissatisfaction with Hypothyroidism Treatment Is Associated with Patient Expectations and Prior Health Care Provider Experiences. Clin. Thyroidol. 2020;32:548–551. doi: 10.1089/ct.2020;32.548-551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitchell A.L., Hegedüs L., Žarković M., Hickey J.L., Perros P. Patient satisfaction and quality of life in hypothyroidism: An online survey by the british thyroid foundation. Clin. Endocrinol. 2021;94:513–520. doi: 10.1111/cen.14340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perros P., Van Der Feltz-Cornelis C., Papini E., Nagy E.V., Weetman A.P., Hegedüs L. The enigma of persistent symptoms in hypothyroid patients treated with levothyroxine: A narrative review. Clin. Endocrinol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/cen.14473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borson-Chazot F., Terra J.L., Goichot B., Caron P. What Is the Quality of Life in Patients Treated with Levothyroxine for Hypothyroidism and How Are We Measuring It? A Critical, Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10:1386. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwarz K., Foltz C.M. Selenium as an Integral Part of Factor 3 against Dietary Necrotic Liver Degeneration. Nutrition. 1957;79:3292–3293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green J., Edwin E.E., Diplock A.T., Bunyan J. Role of selenium in relation to ubiquinone in the rat. Nature. 1961;189:748–749. doi: 10.1038/189748a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hidiroglou M., Jenkins K., Carson R.B., Brossard G.A. Selenium and coenzyme Q10 levels in the tissues of dystrophic and healthy calves. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1967;45:568–569. doi: 10.1139/y67-068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vadhanavikit S., Ganther H.E. Decreased ubiquinone levels in tissues of rats deficient in selenium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;190:921–926. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vadhanavikit S., Ganther H.E. Selenium deficiency and decreased coenzyme Q levels. Mol. Asp. Med. 1994;15((Suppl. 1)):S103–S107. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rani P., Lalitha K. Evidence for altered structure and impaired mitochondrial electron transport function in selenium deficiency. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1996;51:225–234. doi: 10.1007/BF02784077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xing L., Chen C., Li B., Yu H., Chai Z.F. Distribution and location of selenium and other elements in different mitochondrial compartments of human liver by neutron activation analysis. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2006;269:527–534. doi: 10.1007/s10967-006-0260-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Albano D., Treglia G., Giovanella L., Giubbini R., Bertagna F. Detection of thyroiditis on PET/CT imaging: A systematic review. Hormones. 2020;19:341–349. doi: 10.1007/s42000-020-00178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams R., Wright J. Epidemiological issues in health needs assessment. BMJ. 1998;316:1379–1382. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The cited publications of our previous research have appeared as open-source material.