Abstract

Nicotiana benthamiana has emerged as a complementary experimental system to Arabidopsis thaliana. It enables fast-forward in vivo analyses primarily through transient gene expression and is particularly popular in the study of plant immunity. Recently, our understanding of nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) plant immune receptors has greatly advanced following the discovery of the Arabidopsis HOPZ-ACTIVATED RESISTANCE1 (ZAR1) resistosome. Here, we describe a vector system of 72 plasmids that enables functional studies of the ZAR1 resistosome in N. benthamiana. We showed that ZAR1 stands out among the coiled coil class of NLRs (CC-NLRs) for being highly conserved across distantly related dicot plant species and confirmed NbZAR1 as the N. benthamiana ortholog of Arabidopsis ZAR1. Effector-activated and autoactive NbZAR1 triggers the cell death response in N. benthamiana and this activity is dependent on a functional N-terminal α1 helix. C-terminally tagged NbZAR1 remains functional in N. benthamiana, thus enabling cell biology and biochemical studies in this plant system. We conclude that the NbZAR1 open source pZA plasmid collection forms an additional experimental system to Arabidopsis for in planta resistosome studies.

An open source collection of 72 Golden Gate compatible plasmids accelerates discovery by enabling rapid functional and comparative studies of immune receptor complexes.

Introduction

Nicotiana benthamiana has developed into a popular model system in plant biology, particularly for the study of plant immunity. The appeal of N. benthamiana as an experimental system is primarily due to agroinfiltration, a rapid transient protein expression method that enables cell biology, biochemistry, protein–protein interaction analyses, and other in vivo experiments (Goodin et al., 2008). In addition, N. benthamiana is a member of the asterid group of flowering plants and as such is relatively distant from the classic model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, which belongs to the rosid group. Therefore, N. benthamiana is a complementary experimental system to Arabidopsis that also allows for a broader perspective into the evolution of molecular mechanisms in dicot plants.

Plants use nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) proteins to mount innate immunity against invading pathogens. NLRs are intracellular receptors that detect host cell-translocated pathogen effectors and activate a hypersensitive cell death response that is a hallmark of plant immunity. The recent elucidation of the structures of the inactive and active complexes formed by the Arabidopsis NLR protein ZAR1 (HOPZ-ACTIVATED RESISTANCE1) with its partners receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases (RLCKs) is a major breakthrough in understanding how these immune receptors are activated and function. Activated ZAR1 forms a wheel-like pentamer, termed a resistosome, that undergoes a conformational switch—the death switch—to expose a funnel-shaped structure formed by the N-terminal α1 helices (Wang et al., 2019a, 2019b). The funnel of the ZAR1 resistosome forms a pore on the plasma membrane and the resistosome itself acts as a Ca2+ channel (Bi et al., 2021). The N-terminal α1 helix matches a sequence motif known as MADA motif that is functionally conserved across ∼20% of coiled-coil (CC)-type plant NLRs (Adachi et al., 2019). This indicates that the ZAR1 death switch mechanism may be widely conserved across plant species. Mutations in surface-exposed residues within the α1 helix/MADA motif impair cell death and disease resistance mediated by ZAR1 and other MADA-CC-NLRs (Adachi et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019b; Hu et al., 2020).

Here, we describe a Golden Gate compatible vector system (pZA) that enables functional studies of the ZAR1 resistosome in N. benthamiana. Golden Gate enables modular cloning through assembly of DNA fragments in one-step Type IIS restriction enzyme reactions. Consistent with previous reports (Baudin et al., 2017, 2019; Schultink et al., 2019), we confirmed that Arabidopsis ZAR1 (AtZAR1) does not cause hypersensitive cell death in N. benthamiana when expressed on its own and that N. benthamiana carries an ortholog of ZAR1 (NbZAR1). We developed and validated the pZA plasmid collection and share it as an open source resource that should prove useful for functional and comparative studies of NLR resistosomes in plants.

Results and discussion

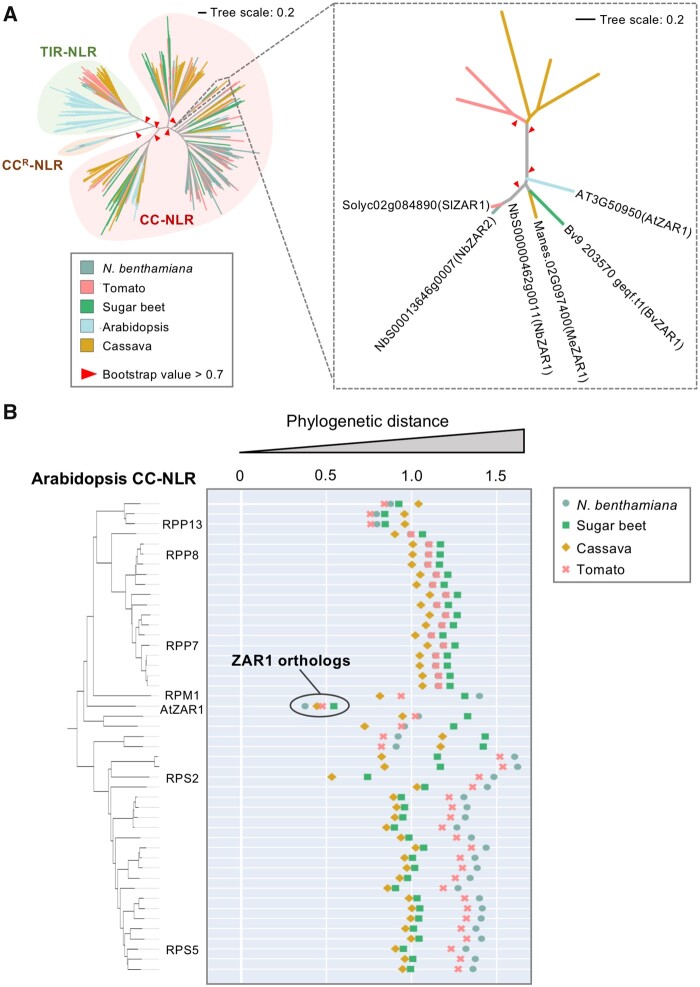

ZAR1 is conserved across distantly related dicot plant species

Baudin et al. (2017) previously reported two orthologs of Arabidopsis ZAR1 and named them NbZAR1 and NbZAR2. We confirmed their findings by performing phylogenetic analyses of NLR proteins using the NB-ARC (nucleotide-binding adaptor shared by APAF-1, certain R gene products and CED-4) domain from five dicot plant species (Arabidopsis, cassava [Manihot esculenta], sugar beet [Beta vulgaris ssp. vulgaris var. altissima], tomato [Solanum lycopersicum], and N. benthamiana) representing three major clades of dicot plants (rosids, aterids, and Caryophyllales). The resulting phylogenetic tree included 829 NLRs, which expectedly clustered into the well-defined NLR classes (Figure 1, A). Arabidopsis ZAR1 (AtZAR1, AT3G50950) fell within a well-supported CC-NLR subclade that included NbZAR1 (NbS00000462g0011), NbZAR2 (NbS00013646g0007), and one gene each from the three other dicot plant species (Figure 1, A). As previously reported (Baudin et al., 2017), NbZAR2 is truncated in the reference N. benthamiana genome (Supplemental Figure S1). The other four genes, NbZAR1, Manes.02G097400 (MeZAR1), Bv9 203570 geqf.t1 (BvZAR1), and Solyc02g084890 (SlZAR1), code for CC-NLR proteins of similar length to AtZAR1, suggesting them as ZAR1 orthologs in each dicot plant species (Supplemental Figure S1).

Figure 1.

ZAR1 is a conserved CC-NLR across distantly related dicot plant species. A, ZAR1 forms a small subclade that is composed of orthologous genes from distantly related dicot plant species. The phylogenetic tree was generated in MEGA7 by the neighbor-joining method using NB-ARC domain sequences of 829 NLRs identified from N. benthamiana (NbS-), tomato (Solyc-), sugar beet (Bv-), Arabidopsis (AT-), and cassava (Manes-) (left panel). The ZAR1 subclade phylogenetic tree is shown on the right panel. Each branch is marked with different colors based on plant species. Red arrow heads indicate bootstrap support >0.7 and are shown for the relevant nodes. The scale bars indicate the evolutionary distance in amino acid substitution per site. Amino acid sequences of the full-length ZAR1 orthologs can be found in Supplemental Figure S1. B, AtZAR1 is highly conserved among dicot CC-NLRs. The phylogenetic (patristic) distances of two CC-NLR nodes between Arabidopsis and other plant species were calculated from the NB-ARC phylogenetic tree in A. The closest patristic distances are plotted with different colors based on plant species. Representative Arabidopsis NLRs are highlighted. The closest patristic distances of two CC-NLR nodes between N. benthamiana and other plant species can be found in Supplemental Figure S2.

Based on our experience, ZAR1 seemed atypical among NLRs for having well-defined orthologs across unrelated dicot species. To directly evaluate ZAR1 conservation relative to other CC-NLRs, we calculated the phylogenetic (patristic) distance between each of the 47 Arabidopsis CC-NLRs and their closest gene from the other plant species based on the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1, A). Interestingly, AtZAR1 stood out among the CC-NLRs as having the shortest phylogenetic distance to its four orthologs (Figure 1, B). Similarly, in a reverse analysis where we plotted the phylogenetic distance between each of the 153 N. benthamiana CC-NLRs to their closest gene from the other species, NbZAR1 again stood out as being exceptionally conserved across all five examined species relative to other N. benthamiana CC-NLRs (Supplemental Figure S2). Multiple alignments of the ZAR1 orthologs from the examined species confirmed the relatively high conservation of ZAR1 with pair-wise sequence similarities ranging from 58% to 86% across the full NLR protein (Supplemental Figure S1). Overall, these analyses confirm NbZAR1 as the N. benthamiana ortholog of AtZAR1 and reveal ZAR1 as possibly the most widely conserved CC-NLR in dicot plants.

Golden Gate compatible plasmids for in vivo ZAR1 resistosome studies

The Golden Gate cloning system enables rapid and high-throughput assembly of multiple sequence modules, such as promotor, terminator, or tags into a common vector (Patron et al., 2015). To facilitate in vivo resistosome studies using this cloning strategy, we first introduced synonymous mutations to BpiI restriction enzyme sites in the coding sequence of AtZAR1 and NbZAR1 to make them both Golden Gate compatible. Next, we generated a synthetic version of NbZAR1, termed NbZAR1syn, for genetic complementation assays in NbZAR1 silencing plants. Shuffled synonymous codon sequences can avoid virus-induced and hairpin RNA-mediated gene silencing (Wu et al., 2016; Derevnina et al., 2021). We cloned the genes into Golden Gate compatible vectors (see Level 0 in Table 1). Each coding sequence was flanked by BsaI restriction enzyme sites and overhang sequences for optimal Golden Gate reactions (Supplemental Figure S3). Therefore, the Level 0 vectors can be used to transfer genes into a variety of Agrobacterium tumefaciens binary vectors for in planta protein expression.

Table 1.

Golden Gate plasmid resources prepared in this study

| Plasmids | Relevant features | Bacterial selection | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| pZA1 | Golden Gate compatible (GG_) wild-type AtZAR1 with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA2 | GG_AtZAR1D489V with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA3 | GG_AtZAR1L17E with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA4 | GG_AtZAR1L17E/D489V with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA5 | GG_wild-type NbZAR1 with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA6 | GG_NbZAR1D481V with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA7 | GG_NbZAR1L17E with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA8 | GG_NbZAR1L17E/D481V with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA9 | GG_wild-type AtZAR1 without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA10 | GG_AtZAR1D489V without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA11 | GG_AtZAR1L17E without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA12 | GG_AtZAR1L17E/D489V without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA13 | GG_wild-type NbZAR1 without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA14 | GG_NbZAR1D481V without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA15 | GG_NbZAR1L17E without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA16 | GG_NbZAR1L17E/D481V without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA17 | GG_wild-type AtZAR1, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA18 | GG_AtZAR1D489V, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA19 | GG_AtZAR1L17E, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA20 | GG_AtZAR1L17E/D489V, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA21 | GG_wild-type NbZAR1, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA22 | GG_NbZAR1D481V, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA23 | GG_NbZAR1L17E, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA24 | GG_NbZAR1L17E/D481V, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA25 | GG_wild-type AtZAR1-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA26 | GG_AtZAR1D489V-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA27 | GG_AtZAR1L17E-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA28 | GG_AtZAR1L17E/D489V-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA29 | GG_wild-type NbZAR1-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA30 | GG_NbZAR1D481V-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA31 | GG_NbZAR1L17E-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA32 | GG_NbZAR1L17E/D481V-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA33 | GG_wild-type AtZAR1-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA34 | GG_AtZAR1D489V-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA35 | GG_AtZAR1L17E-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA36 | GG_AtZAR1L17E/D489V-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA37 | GG_wild-type NbZAR1-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA38 | GG_NbZAR1D481V-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA39 | GG_NbZAR1L17E-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA40 | GG_NbZAR1L17E/D481V-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA41 | GG_wild-type AtZAR1-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA42 | GG_AtZAR1D489V-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA43 | GG_AtZAR1L17E-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA44 | GG_AtZAR1L17E/D489V-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA45 | GG_wild-type NbZAR1-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA46 | GG_NbZAR1D481V-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA47 | GG_NbZAR1L17E-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA48 | GG_NbZAR1L17E/D481V-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA49 | GG_synthesized NbZAR1 (NbZAR1syn) with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA50 | GG_NbZAR1syn-D481V with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA51 | GG_NbZAR1syn-L17E with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA52 | GG_NbZAR1syn-L17E/D481V with STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA53 | GG_NbZAR1syn without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA54 | GG_NbZAR1syn-D481V without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA55 | GG_NbZAR1syn-L17E without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA56 | GG_NbZAR1syn-L17E/D481V without STOP codon | Spcr | Level 0 |

| pZA57 | GG_NbZAR1syn-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA58 | GG_NbZAR1syn-D481V-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA59 | GG_NbZAR1syn-L17E-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA60 | GG_NbZAR1syn-L17E/D481V-4xMyc, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA61 | GG_NbZAR1syn-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA62 | GG_NbZAR1syn-D481V-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA63 | GG_NbZAR1syn-L17E-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA64 | GG_NbZAR1syn-L17E/D481V-6xHA, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA65 | GG_NbZAR1syn-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA66 | GG_NbZAR1syn-D481V-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA67 | GG_NbZAR1syn-L17E-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA68 | GG_NbZAR1syn-L17E/D481V-eGFP, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA69 | Intron-containing hairpin RNA (ihpRNA)-NbZAR1 | Kmr | RNAi |

| pZA70 | ihpRNA-NbJIM2 | Kmr | RNAi |

| pZA71 | GG_synthesized NbJIM2 (NbJIM2syn)-3xFLAG, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

| pZA72 | GG_XopJ4, Kmr plant selection marker | Kmr | Level 2 |

Spcr, spectinomycin-resistant; Kmr, kanamycin-resistant.

To activate ZAR1 in the N. benthamiana system, we cloned an RLCK XII protein NbJIM2 (XOPJ4 IMMUNITY 2) and Xanthomonas perforans effector XopJ4 with Golden Gate compatible sequences (Table 1). NbJIM2 is an endogenous partner RLCK associating with NbZAR1 and is required for XopJ4 recognition in N. benthamiana (Schultink et al., 2019). As an alternative strategy for activating ZAR1, we generated autoactive ZAR1 by mutating the MHD motif, which is conserved across ZAR1 orthologs (Supplemental Figure S1). Substitution from aspartic acid (D) to valine (V) in the MHD motif generally makes full-length NLRs autoactive (Tameling et al., 2006). MHD mutants of AtZAR1, NbZAR1, and NbZAR1syn (AtZAR1D489V, NbZAR1D481V, and NbZAR1syn-D481V) were cloned into Level 0 vectors (Table 1).

We also generated an inactive version of ZAR1 by substituting leucine 17 to glutamic acid mutation (L17E) in the N-terminal MADA motif, since mutations in the N-terminal MADA motif often impair NLR cell death activity (Supplemental Figure S1; Adachi et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019b). We generated a MADA-mutant series in wild-type and MHD-mutant backgrounds, namely MADA mutants (AtZAR1L17E, NbZAR1L17E, and NbZAR1syn-L17E) and MADA/MHD mutants (AtZAR1L17E/D489V, NbZAR1L17E/D481V, and NbZAR1syn-L17E/D481V) (Level 0 in Table 1).

We assembled all of the ZAR1 genes into binary vector plasmids without epitope tags or with the C-terminal tags 4xMyc, 6xHA, and eGFP (pZA17-48 and pZA57-68 in Table 1). We provide this collection of 72 plasmids (Table 1) as an open access resource for in planta ZAR1 resistosome studies.

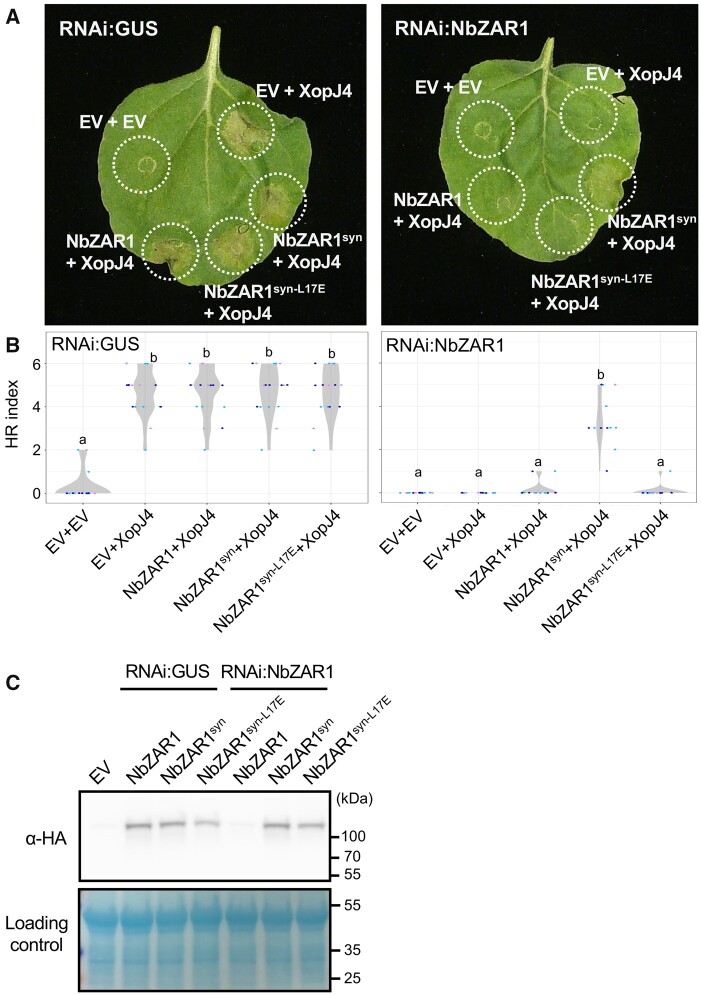

Golden Gate-based genetic complementation assay evaluates effector-activated ZAR1 cell death in N. benthamiana

To validate constructs generated by the Golden Gate assembly, we first tested whether XopJ4-triggered cell death is dependent on NbZAR1 in the N. benthamiana transient expression system. We used a hairpin-silencing construct (RNAi:NbZAR1) that mediates silencing of NbZAR1 when transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaves (Supplemental Figure S4). Silencing of NbZAR1 suppressed cell death triggered by XopJ4, compared with the RNAi:GUS silencing control (Figure 2, A and B). We further performed an agroinfiltration complementation assay using a silencing-resilient version of NbZAR1 (NbZAR1syn). Unlike the original NbZAR1, NbZAR1syn complemented the cell death response triggered by XopJ4 in NbZAR1 silencing leaves (Figure 2, A and B). Consistent with this genetic complementation phenotype, NbZAR1syn was expressed in the RNAi:NbZAR1 background at a similar level to the RNAi:GUS control (Figure 2, C). These results indicate that our construct series enables functional studies of the ZAR1 resistosome in the N. benthamiana transient expression system.

Figure 2.

The NbZAR1 MADA motif mediates XopJ4-triggered cell death in N. benthamiana. A, Cell death observed in N. benthamiana leaves after expression of ZAR1 and XopJ4. The leaves were infiltrated with Agrobacterium strains carrying ZAR1 and XopJ4 overexpression constructs at 1 d after initial agroinfiltration of RNAi constructs. Nicotiana benthamiana leaf panels expressing non-epitope-tagged wild-type and variant proteins of NbZAR1 were photographed at 5 d after the second agroinfiltration. B, Violin plots showing cell death intensity scored as an HR index based on three independent experiments. Statistical differences among the samples were analyzed with Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.01). C, In planta protein accumulation of wild-type NbZAR1 and the variant. For anti-HA immunoblot, total proteins were prepared from N. benthamiana leaves at 2 d after the second agroinfiltration. Empty vector control is described as EV. Equal loading was checked with Reversible Protein Stain Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

L17E mutation in NbZAR1 N-terminal α1 helix impairs XopJ4-triggered cell death in N. benthamiana

Given that mutations in surface-exposed residues within the N-terminal α1 helix/MADA motif impair cell death by Arabidopsis ZAR1 (Wang et al., 2019b), we hypothesized that the intact α1 helix is required for NbZAR1-mediated cell death in response to XopJ4. To test this hypothesis, we used a MADA-mutant NbZAR1syn-L17E in the complementation assay of RNAi:NbZAR1. Unlike NbZAR1syn, NbZAR1syn-L17E did not complement the XopJ4-triggered cell death response in RNAi:NbZAR1 leaves (Figure 2, A and B). We confirmed that NbZAR1syn-L17E protein was expressed in NbZAR1 silencing leaves (Figure 2, C). Thus, we conclude that similar to Arabidopsis ZAR1, the N-terminal α1 helix/MADA motif in activated NbZAR1 mediates the cell death response in N. benthamiana.

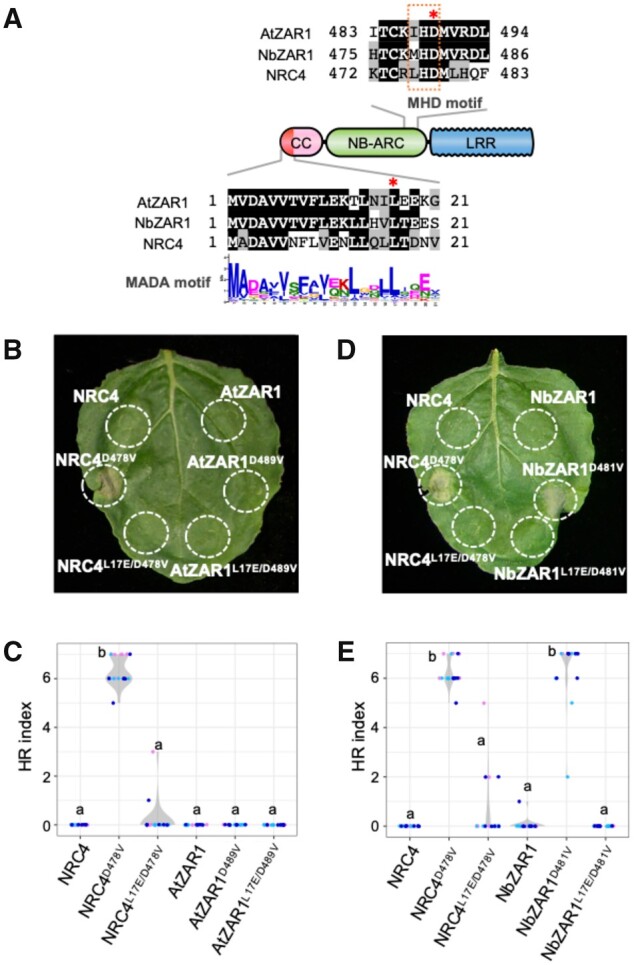

Unlike Arabidopsis ZAR1, NbZAR1 triggers autoimmune cell death in N. benthamiana

Next, we investigated the effect of a MHD mutation on AtZAR1 and NbZAR1 autoimmunity in the N. benthamiana system (Figure 3, A). As recently reported by Baudin et al. (2019), AtZAR1 did not trigger macroscopic cell death in N. benthamiana leaves even when the full-length protein carries the D489V mutation in the MHD motif (Figure 3, B and C). In contrast, NbZAR1 caused macroscopic cell death when the MHD mutant NbZAR1D481V was expressed in N. benthamiana leaves (Figure 3, D and E). NRC4 (NLR required for cell death 4) was used as a control MADA-CC-NLR, because its MHD mutant NRC4D478V causes autoactive cell death in N. benthamiana leaves (Adachi et al., 2019). Our results indicate that unlike Arabidopsis ZAR1, full-length NbZAR1 can be made autoactive in N. benthamiana through mutation of the MHD motif. These results are consistent with a previous report that AtZAR1 does not complement NbZAR1 cell death activity when co-expressed with XopJ4/JIM2 (Schultink et al., 2019). We conclude that unlike AtZAR1, NbZAR1 is probably compatible with endogenous RLCK and can therefore display autoactivity when expressed on its own in N. benthamiana leaves.

Figure 3.

NbZAR1 triggers autoimmune cell death in N. benthamiana leaves and requires an intact MADA motif for autoactivity. A, Schematic representation of substitution sites in AtZAR1, NbZAR1, and NRC4. Mutated sites are shown with red asterisks on the sequence alignment. B and D, Cell death observed in N. benthamiana leaves after expression of ZAR1 mutants. Nicotiana benthamiana leaf panels expressing non-epitope-tagged wild-type and variant proteins of AtZAR1 and NbZAR1 were photographed at 5 d after agroinfiltration. C and E, Violin plots showing cell death intensity scored as an HR index based on three independent experiments. Statistical differences among the samples were analyzed with Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.01).

The endogenous RLCK partner JIM2 is required for NbZAR1 autoimmune cell death

To test the hypothesis that the endogenous RLCK partner is required for NbZAR1 autoactivity (Schultink et al., 2019), we used RNAi:NbJIM2 (Supplemental Figure S4) and coexpressed the hairpin silencing construct with autoactive NbZAR1D481V. Compared with the RNAi:GUS silencing control, RNAi:NbJIM2 significantly reduced cell death by NbZAR1D481V (Supplemental Figure S5). Moreover, a synthetic version of NbJIM2 with a codon shuffled sequence (NbJIM2syn) restored the NbZAR1D481V autoimmune cell death response (Supplemental Figure S5). Although a pathogen effector was not used to activate NbZAR1, this experiment shows that autoactive NbZAR1 is dependent on its partner RLCK NbJIM2. This indicates that NbZAR1D481V may require an RLCK to form a signaling competent conformation like the AtZAR1 resistosome (Wang et al., 2019a, 2019b).

NbZAR1 autoimmune cell death is dependent on its N-terminal α1 helix

Next, we tested whether NbZAR1 requires an intact N-terminal α1 helix/MADA motif for triggering autoactive cell death. We expressed the double MADA/MHD mutant NbZAR1L17E/D481V in N. benthamiana leaves using agroinfiltration and observed that the L17E mutation significantly reduced the cell death activity compared with NbZAR1D481V (Figure 3, D and E). This result indicates that an intact N-terminal α1 helix is necessary for NbZAR1D481V autoactivity. Given that the α1 helix forms a funnel-shaped structure that is a key structural component of the activated ZAR1 resistosome and its translocation into the plasma membrane (Wang et al., 2019b), we conclude that the NbZAR1D481V experimental system recapitulates the resistosome model in N. benthamiana.

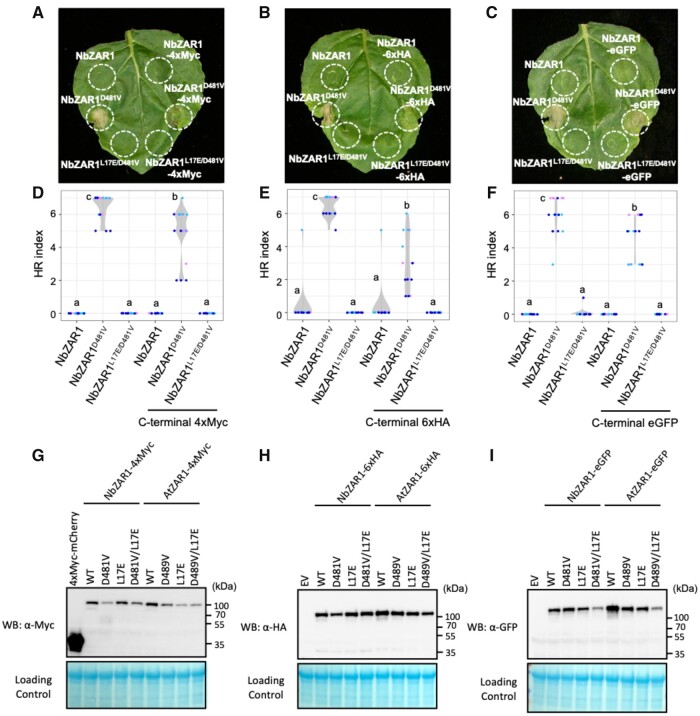

C-terminally tagged NbZAR1 is functional in N. benthamiana

Nicotiana benthamiana agroinfiltration is a powerful method for in vivo cell biology, biochemistry, and protein–protein interaction analyses, but this experimental system requires that the target protein remains functional and intact after fusion to an epitope or fluorescent tag (Goodin et al., 2008; Bally et al., 2018). We therefore set out to determine the degree to which NbZAR1 can tolerate protein tags (Table 1). We focused on C-terminal tags, given that N-terminal tag fusion is known to interfere with the AtZAR1 cell death activity (Wang et al., 2019b). We tested NbZAR1D481V constructs fused to three different tags, 4xMyc, 6xHA, and eGFP by agroinfiltration. In all three cases, NbZAR1D481V retained the capacity to trigger autoactive cell death although the response was weaker than the non-epitope-tagged NbZAR1 positive control (Figure 4, A–F). We also showed by western blot analyses that these C-terminally tagged NbZAR1 accumulated at detectable levels in N. benthamiana leaves and generally formed a single band indicative of minimal protein degradation (Figure 4, G–I). We conclude that C-terminal tagging of NbZAR1 doesn’t dramatically interfere with the activity and integrity of this NLR protein.

Figure 4.

C-terminal tagged NbZAR1 triggers autoimmune cell death in N. benthamiana leaves. A–C, Cell death observed in N. benthamiana leaves after expression of ZAR1 mutants. Nicotiana benthamiana leaf panels expressing wild-type and variant proteins of NbZAR1 with C-terminal 4xMyc, 6xHA, or eGFP tag were photographed at 5 d after agroinfiltration. D–F, Violin plots showing cell death intensity scored as an HR index based on three independent experiments. Statistical differences among the samples were analyzed with Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.01). G–I, In planta protein accumulation of AtZAR1 and NbZAR1 variants. For anti-Myc, anti-HA, and anti-GFP immunoblots of AtZAR1, NbZAR1, and the mutant proteins, total proteins were prepared from N. benthamiana leaves at 2 d after agroinfiltration. Empty vector control is described as EV. Equal loading was checked with Reversible Protein Stain Kit (Thermo Fisher).

Toward in vivo studies of the ZAR1 resistosome

We conclude that the open source pZA plasmid resource we developed can serve as valuable reagents for in vivo resistosome studies in N. benthamiana that complements the Arabidopsis system and provides a foundation for future studies. Effector-activated and autoactive NbZAR1 can be readily tested by agroinfiltration in N. benthamiana leaves and assayed for cell death activity. This indicates the effectiveness of our plasmid resource to monitor the activated state of ZAR1 in the N. benthamiana system. We also note one advantage of the ZAR1 MADA mutants, which are presumably activated but unable to trigger cell death. This mutation strategy enables protein purification or microscopic observation of effector-activated/autoactive ZAR1 using plant tissues without cell death response that generally perturbs biochemical and cell biology studies. Since NbZAR1D481V tolerates different C-terminal tags and each variant protein expresses well in N. benthamiana, the pZA plasmid resource can be applied for in planta cell biology, biochemical, and protein–protein interactions studies of the ZAR1 resistosome.

The pZA toolkit complements existing resources in Arabidopsis. Of particular interest is the visualization of activated NLR oligomers in vivo. Recently, an ∼900 kDa complex associated with activated AtZAR1 was detected in Blue Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) analysis using Arabidopsis protoplasts (Hu et al., 2020). Bi et al. (2021) monitored subcellular dynamics of AtZAR1 resistosomes on the plasma membrane in Arabidopsis protoplasts under total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Nicotiana benthamiana agroinfiltration offers a rapid and effective alternative expression system to the Arabidopsis protoplast system used by Hu et al. (2020) and Bi et al. (2021) that can be explored in the future.

Nicotiana benthamiana is rapidly developing as an excellent experimental system to study oligomeric complexes by different types of NLRs. Jacob et al. (2021) detected oligomer formation of a CCR-NLR (RPW8-type CC-NLR) AtNRG1.1 (N REQUIREMENT GENE 1.1) in BN-PAGE when they expressed an AtNRG1.1 autoactive MHD mutant in N. benthamiana leaves. Imaging analysis showed AtNRG1.1 MHD mutant forms punctate structures on the plasma membrane of N. benthamiana epidermal cells (Jacob et al., 2021). Martin et al. (2020) solved a cryo-electron microscopy structure of activated TIR-NLR (Toll/interleukin-1 receptor-NLR) ROQ1 (RECOGNITION OF XOPQ 1) by purifying activated ROQ1 protein from N. benthamiana leaves. Therefore, the N. benthamiana system has potential as a protein expression platform for structural studies of both resting and activated states of NLRs in vivo.

Here, we describe that ZAR1 stands out among CC-NLRs for being widely conserved across dicot plants. Recently, we expanded on these analyses and reconstructed the evolutionary history of ZAR1 across angiosperms (Adachi et al., 2021). Notably, ZAR1 orthologs were identified not only from dicot plant species but also from a monocot, taro (Colocasia esculenta). Thus, we conclude that the origin of ZAR1 traces back to early flowering plant linages ∼220 to 150 million years ago (Jurassic period). However, it still remains unknown how ZAR1 orthologs vary in their molecular and biochemical activities among flowering plant species. The pZA system enables evolutionary studies of the ZAR1 resistosome. Further comparative analyses between AtZAR1, NbZAR1, and other orthologs would help answer questions about the molecular evolution of the resistosome as a mechanism to trigger NLR-mediated immunity.

Materials and methods

Plant growth conditions

Wild-type N. benthamiana was propagated in a glasshouse and, for most experiments, grown in a controlled growth chamber with temperatures of 22°C–25°C, humidity 45%–65%, and a 16/8-h light/dark cycle.

Bioinformatic and phylogenetic analyses

We used NLR-parser (Steuernagel et al., 2015) to identify NLR sequences from the protein databases of tomato (Sol Genomics Network, Tomato ITAG release 2.40), N. benthamiana (Sol Genomics Network, N. benthamiana Genome v0.4.4), A. thaliana (https://www.araport.org/, Araport11), cassava (M. esculenta) (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/, Phytozome v13, Manihot esculenta v7.1), and sugar beet (B. vulgaris ssp. vulgaris var. altissima) (http://bvseq.molgen.mpg.de/index.shtml, RefBeet-1.2). The obtained NLR sequences from NLR-parser were aligned using MAFFT v. 7 (Katoh and Standley, 2013), and the protein sequences that lacked the p-loop motif were discarded to make the NLR dataset (Supplemental File S1). The gaps in the alignments were deleted manually in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016) and the NB-ARC domains were used for generating phylogenetic trees (Supplemental File S2). The neighbor-joining tree was made using MEGA7 with JTT model and bootstrap values based on 100 iterations (Supplemental File S3). Amino acid sequences of ZAR1 orthologs and the percent identity are listed in Supplemental Files S4, S5.

To calculate the phylogenetic (patristic) distance, we used Python script based on DendroPy (Sukumaran and Holder, 2010). We calculated patristic distances from each CC-NLR to the other CC-NLRs on the phylogenetic tree (Supplemental File S3) and extracted the distance between CC-NLRs of Arabidopsis or N. benthamiana to the closest NLR from the other plant species. The script used for the patristic distance calculation is available from GitHub (https://github.com/slt666666/Phylogenetic_distance_plot).

Plasmid constructions

For Golden Gate cloning system, wild-type and MHD-mutant clones of AtZAR1 and NbZAR1 were synthesized through GENEWIZ Standard Gene Synthesis with synonymous mutations to BpiI restriction enzyme sites. The synthetic fragment of NbZAR1 was designed manually to introduce synonymous substitution by following N. benthamiana codon usage. The fragment was synthesized through GENEWIZ Standard Gene Synthesis and then subcloned into pICSL01005 (Level 0 acceptor for CDS no stop modules, Addgene no.47996) or pICH41308 (Level 0 acceptor for CDS modules, Addgene no.47998) together with the remaining NbZAR1 fragment to generate full-length NbZAR1syn. Primers used for amplifying the NbZAR1 fragment are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

To generate MADA motif mutants of AtZAR1 and NbZAR1, the leucine (L) 17 in the MADA motif was substituted to glutamic acid (E) by site-directed mutagenesis using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To make AtZAR1 and NbZAR1 clones for C-terminal tagging, the stop codons were removed by PCR using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All wild-type and mutant cording sequences of AtZAR1 and NbZAR1 were cloned into pCR8/GW/D-TOPO (Invitrogen) as level 0 modules (Weber et al., 2011). Primers used for the site-directed mutagenesis and removing the stop codon are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

The level 0 plasmids of AtZAR1, NbZAR1, and NbZAR1syn were used for Golden Gate assembly with or without C-terminal tag modules, pICSL50009 (6xHA, Addgene no. 50309), pICSL50010 (4xMyc, Addgene no. 50310), or pICSL50034 (eGFP, TSL SynBio) into the binary vector pICH86988 (Engler et al., 2014).

Golden Gate compatible XopJ4 and NbJIM2syn clones were synthesized through GENEWIZ Standard Gene Synthesis and were subcloned into the pICH86988 vector. pICSL50007 (3xFLAG, Addgene no. 50308) was used to make the C-terminal 3xFLAG fusion construct of NbJIM2syn.

To prepare the RNAi construct, the silencing fragments were amplified from NbZAR1 and NbJIM2 cDNA by Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using primers listed in Supplemental Table S1. The purified amplicons were cloned into the pRNAi-GG vector (Yan et al., 2012).

Transient gene-expression and cell death assays

Transient gene expression in N. benthamiana was performed by agroinfiltration according to methods described by Bos et al. (2006). Briefly, 4-weeks old N. benthamiana plants were infiltrated with A. tumefaciens Gv3101 strains carrying the binary expression plasmids. Agrobacterium tumefaciens suspensions were prepared in infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, and 150 μM acetosyringone, pH5.6) and were adjusted to OD600 = 0.5. Macroscopic cell death phenotypes were scored according to the scale of Segretin et al. (2014) modified to range from 0 (no visible necrosis) to 7 (fully confluent necrosis).

To perform genetic complementation assays in RNAi:NbZAR1 and RNAi:NbJIM2 backgrounds, we initially infiltrated A. tumefaciens strains carrying RNAi constructs (OD600 = 0.5). At 1 d after the first agroinfiltration, we performed second agroinfiltration using mixtures of two different A. tumefaciens strains to complement NbZAR1/NbJIM2 expression and overexpress cell death triggering genes. In this second agroinfiltration, we adjusted the final concentration of each A. tumefaciens suspension to OD600 = 0.3.

RNA extraction and semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Plant total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). A total of 500 ng RNA of each sample was subjected to reverse transcription using SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Semi-quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) was performed using DreamTaq (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 22, 32, and 36 amplification cycles for EF-1α, NbJIM2, and NbZAR1, respectively. Primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Protein immunoblotting

Protein samples were prepared from six discs (8 mm diameter) cut out of N. benthamiana leaves at 2 d after agroinfiltration and were homogenized in extraction buffer (10% [v/v] glycerol, 25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 2% [w/v] PVPP, 10 mM DTT, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail [SIGMA], 0.5% [v/v] IGEPAL [SIGMA]). The supernatant obtained after centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min was used for SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was performed with HA-probe (F-7) HRP (Santa Cruz Biotech), c-Myc (9E10) HRP (Santa Cruz Biotech), or GFP (B-2) HRP (Santa Cruz Biotech) in a 1:5,000 dilution. Equal loading was checked by taking images of the stained PVDF (polyvinylidene difluoride) membranes with Pierce Reversible Protein Stain Kit (#24585, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Plasmid distribution

All pZA plasmids are available through Addgene through the Kamoun Lab page https://www.addgene.org/Sophien_Kamoun/.

Statistical analyses

HR indexes were visualized as a violin plot using the “ggplot2” package (Wickham, 2016). Tukey’s HSD test was applied to HR indexes using the “TukeyHSD” function in R (version 3.6).

Accession numbers

DNA sequence data used in this study can be found in reference genome or GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: AtZAR1 (AT3G50950, NP_190664.1), NbZAR1 (NbS00000462g0011, AXY05280.1), NbZAR2 (NbS00013646g0007), SlZAR1 (Solyc02g084890, XP_004232433.1), MeZAR1 (Manes.02G097400, P_021604862.1), BvZAR1 (Bv9_203570_geqf.t1, XP_010688776.1), NbJIM2 (NbS00009407g0011, MH532571.1), and XopJ4 (AF221058.1).

Supplemental data

Supplemental Figure S1. Sequence alignment of full-length ZAR1 ortholog proteins.

Supplemental Figure S2. NbZAR1 is highly conserved across dicot species.

Supplemental Figure S3. Golden Gate level 0 modules of AtZAR1 and NbZAR1 genes.

Supplemental Figure S4. NbZAR1 and NbJIM2 silencing in N. benthamiana.

Supplemental Figure S5. NbJIM2 is required for NbZAR1 autoactive cell death in N. benthamiana.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used for generating Golden Gate constructs in this study.

Supplemental File S1. Amino acid sequences of full-length NLRs in the NLR dataset.

Supplemental File S2. Amino acid sequences for NLR phylogenetic tree.

Supplemental File S3. NLR phylogenetic tree file.

Supplemental File S4. Amino acid sequences of ZAR1 orthologs.

Supplemental File S5. Percent identity matrix of ZAR1 orthologs by Clustal2.1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to several colleagues especially Sophien Kamoun’s group members for discussions and ideas. We also thank Mark Youles of TSL SynBio for invaluable technical support and Mauricio Contreras for suggesting the pZA name.

Funding

This work was funded by the Gatsby Charitable Foundation (S.K., TSL), Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (S.K., BBS/E/J/000PR9795 and BB/V002937/1), and European Research Council (S.K., NGRB and BLASTOFF).

Conflict of interest statement. S.K. receives funding from industry on NLR biology.

S.K. and H.A. designed the research, supervised the work, and wrote the manuscript. A.H., H.P., T.S., and H.A. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. All authors read and edited the manuscript.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/General-Instructions) is Hiroaki Adachi (adachi.hiroaki@bs.naist.jp).

References

- Adachi H, Contreras MP, Harant A, Wu CH, Derevnina L, Sakai T, Duggan C, Moratto E, Bozkurt TO, Maqbool A, et al. (2019) An N-terminal motif in NLR immune receptors is functionally conserved across distantly related plant species. eLife 8:e49956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi H, Sakai T, Kourelis J, Gonzalez Hernandez JL, Maqbool A, Kamoun S (2021) Jurassic NLR: conserved and dynamic evolutionary features of the atypically ancient immune receptor ZAR1. bioRxiv preprint 10.1101/2020.10.12.333484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bally J, Jung H, Mortimer C, Naim F, Philips JG, Hellens R, Bombarely A, Goodin MM, Waterhouse PM (2018) The rise and rise of Nicotiana benthamiana: a plant for all reasons. Annu Rev Phytopathol 56:405–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin M, Hassan JA, Schreiber KJ, Lewis JD (2017) Analysis of the ZAR1 immune complex reveals determinants for immunity and molecular interactions. Plant Physiol 174:2038–2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin M, Schreiber KJ, Martin EC, Petrescu AJ, Lewis JD (2019) Structure–function analysis of ZAR1 immune receptor reveals key molecular interactions for activity. Plant J 101:352–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi G, Su M, Li N, Liang Y, Dang S, Xu J, Hu M, Wang J, Zou M, Deng Y, et al. (2021) The ZAR1 resistosome is a calcium-permeable channel triggering plant immune signaling. Cell 184:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos JI, Kanneganti TD, Young C, Cakir C, Huitema E, Win J, Armstrong MR, Birch PR, Kamoun S (2006) The C-terminal half of Phytophthora infestans RXLR effector AVR3a is sufficient to trigger R3a-mediated hypersensitivity and suppress INF1-induced cell death in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant J 48:165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derevnina L, Contreras MP, Adachi H, Upson J, Cruces AV, Xie R, Sklenar J, Menke FLH, Mugford ST, MacLean D, et al. (2021) Plant pathogens convergently evolved to counteract redundant nodes of an NLR immune receptor network. bioRxiv preprint 10.1101/2021.02.03.429184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler C, Youles M, Gruetzner R, Ehnert TM, Werner S, Jones JD, Patron NJ, Marillonnet S (2014) A golden gate modular cloning toolbox for plants. ACS Synth Biol 3:839–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodin MM, Zaitlin D, Naidu RA, Lommel SA (2008) Nicotiana benthamiana: its history and future as a model for plant–pathogen interactions. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 21:1015–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Qi J, Bi G, Zhou JM (2020) Bacterial effectors induce oligomerization of immune receptor ZAR1 in vivo. Mol Plant 13:793–801 (pii: S1674-2052(20)30066-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob P, Kim NH, Wu F, El-Kasmi F, Chi Y, Walton WG, Furzer OJ, Lietzan AD, Sunil S, Kempthorn K, et al. (2021) Plant “helper” immune receptors are Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channels. Science 17:eabg7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30:772–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Qi T, Zhang H, Liu F, King M, Toth C, Nogales E, Staskawicz BJ (2020) Structure of the activated ROQ1 resistosome directly recognizing the pathogen effector XopQ. Science 370:eabd9993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patron NJ, Orzaez D, Marillonnet S, Warzecha H, Matthewman C, Youles M, Raitskin O, Leveau A, Farré G, Rogers C, et al. (2015) Standards for plant synthetic biology: a common syntax for exchange of DNA parts. New Phytol 208:13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultink A, Qi T, Bally J, Staskawicz B (2019) Using forward genetics in Nicotiana benthamiana to uncover the immune signaling pathway mediating recognition of the Xanthomonas perforans effector XopJ4. New Phytol 221:1001–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segretin ME, Pais M, Franceschetti M, Chaparro-Garcia A, Bos JI, Banfield MJ, Kamoun S (2014) Single amino acid mutations in the potato immune receptor R3a expand response to Phytophthora effectors. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 27:624–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuernagel B, Jupe F, Witek K, Jones JD, Wulff BB (2015) NLR-parser: rapid annotation of plant NLR complements. Bioinformatics 31:1665–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukumaran J, Holder MT (2010) DendroPy: a Python library for phylogenetic computing. Bioinformatics 26:1569–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tameling WI, Vossen JH, Albrecht M, Lengauer T, Berden JA, Haring MA, Cornelissen BJ, Takken FL (2006) Mutations in the NB-ARC domain of I-2 that impair ATP hydrolysis cause autoactivation. Plant Physiol 140:1233–1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang J, Hu M, Shan W, Qi J, Wang G, Han Z, Qi Y, Gao N, Wang H-W, et al. (2019a) Ligand-triggered allosteric ADP release primes a plant NLR complex. Science 364:eaav5868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Hu M, Wang J, Qi J, Han Z, Wang G, Qi Y, Wang H-W, Zhou J-M, Chai J (2019b) Reconstitution and structure of a plant NLR resistosome conferring immunity. Science 364:eaav5870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber E, Engler C, Gruetzner R, Werner S, Marillonnet S (2011) A modular cloning system for standardized assembly of multigene constructs. PLoS ONE 6:e16765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H (2016) ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York. ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4 [Google Scholar]

- Wu CH, Belhaj K, Bozkurt TO, Birk MS, Kamoun S (2016) Helper NLR proteins NRC2a/b and NRC3 but not NRC1 are required for Pto-mediated cell death and resistance in Nicotiana benthamiana. New Phytol 209:1344–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan P, Shen W, Gao X, Li X, Zhou P, Duan J (2012) High-throughput construction of intron- containing hairpin RNA vectors for RNAi in plants. PLoS ONE 7:e38186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.