Abstract

This study investigated adolescents’ own and parental expectations about cross-group friendships between peers from different socio-economic status (SES). Nepalese adolescents (N = 389, Mage = 14.08; grades: 7–10) evaluated an ambiguous peer encounter between a low and a high SES peer. Overall, adolescents attributed negative intentions to high-SES more than to low-SES peers. Most adolescents expected that high- and low-SES targets could not be friends, that parents of high-SES targets would disapprove of cross-group friendships, referencing social hierarchies and reputation, and that parents of low-SES targets would support friendship citing moral concerns and social mobility. Most adolescents were aware of systemic reasons that underlie SES biases. Given that low SES adolescents often suffer when excluded from peer experiences, these findings indicate that parental socialization strategies should focus not only on protecting children from experiences of discrimination but also from experiences related to social inequalities and a lack of social mobility.

Keywords: Cross-group friendship, Parental expectations, Social inequality, Social mobility, Morality

Economists and political scientists have demonstrated the detrimental effects of social inequalities on adolescents’ healthy development (e.g., Duncan & Murnane, 2011). Such inequalities reflect power imbalances in social systems (Kraus & Keltner, 2013) that contribute to the marginalization of social minority groups. Youth experiencing marginalization face numerous disadvantages, such as exclusion, oppression or discrimination by those who are in power and control over resources. Depending on the social context studied, these marginalized groups reflect different social identity categories, such as race, ethnicity, culture, sex, religion, and socio-economic status (SES), and are at high risk for negative youth development (Causadias & Umaña-Taylor, 2018). As the phenomenon of marginalization is at least partly rooted in biases towards underrepresented groups, social policy designed to reduce social inequalities benefits from understanding the psychological origins of individuals’ beliefs that rectify or perpetuate such disparities. A recent burgeoning of research has been conducted on how adolescents understand and evaluate societal inequalities related to the distribution of wealth among the population (Arsenio, 2018).

However, surprisingly little is known regarding adolescents’ beliefs and perceptions about the marginalized group of individuals at the bottom of the social and economic systems (Kraus & Keltner, 2013), namely adolescents from low SES, since SES has only recently been studied as social identity category from a developmental science perspective (see Ruck et al., 2019). Most research on SES as a group identity variable has shown that adolescents use wealth cues to categorize individuals as members of distinct statuses and increasingly associate information on social activities and personal qualities with SES (Mistry et al., 2015; Sigelman, 2012). Therefore, SES may be a particular salient social category in defining adolescents’ peer relations. Still, it remains unclear whether adolescents’ perceptions of SES affect their peer relations (Ghavami & Mistry, 2019) and how they view parental expectations about such relationships.

While there is evidence that parents represent important socialization agents for their children’s peer relationships (Hughes, et al. 2006), almost no research focuses on adolescents’ perceptions of parental messages to children about SES. A long tradition of research on ethnic-racial socialization (ERS) has examined how parents transmit information regarding race and ethnicity to their children (Hughes et al., 2006) and how this shapes their identity formation (Rivas-Drake & Umaña-Taylor, 2019). This research has demonstrated how parents of ethnic minority groups prepare their children for potential discrimination and barriers related to social hierarchies and social stratification (Hughes et al., 2006; Quintana & Vera, 1999; Rivas-Drake & Umaña-Taylor, 2019). However, this work was predominantly focused on race and ethnicity and little is known about ERS regarding other marginalized groups.

We propose that studying ERS in the context of social inequalities (i.e., beliefs about SES) may add new insights on how adolescents experiencing marginalization perceive the various messages about social obstacles they may face, which in turn reproduce inequalities by limiting beliefs about social mobility (Duncan & Murname, 2011; Ruck et al., 2019). In particular, it remains an open question whether adolescents perceive parents as approving or disapproving of friendships between peers from different socioeconomic status groups (i.e., low and high SES). Furthermore, surprisingly little is known about parental socialization and adolescents’ perceptions of SES outside North American and European contexts. A salient and pressing issue in strongly hierarchical societies is whether adolescents view their parents as supporting friendships across socioeconomic status categories (high and low). Similar to the phenomenon of marginalization in which it depends on the socio-historical context which specific groups are marginalized (Causadias & Umaña -Taylor, 2018), parental perspectives may vary depending on the specific intergroup context and the societal opportunities and constraints social groups face (Hughes et al., 2006).

The current study extended prior research on ERS by focusing on SES and by investigating how adolescents perceive parental messages regarding cross-wealth peer interactions in Nepal, a country with a long history of societal and structural inequalities identified by socioeconomic status. Given that cross-group friendships foster positive intergroup attitudes and reduce intergroup biases (Turner & Cameron, 2016), negative parental expectations for cross-group friendships limit the opportunity for reducing bias based on SES, which has been shown to be a pervasive source of marginalization in adolescence (Arsenio & Willems, 2017).

Growing Up with Social Hierarchies: Consequences for Adolescent Development

Based on recent evidence, we theorized that restrictive social rules associated with social status would influence adolescents’ expectations about cross-group interactions. A study on social hierarchies in India, with children in grades 3 to 11, found that children had strong preferences to interact with high-status rather than low-status group members that were consistent with existing status hierarchies (Dunham et al., 2014). Moreover, the majority of participants expected that most people would have positive stereotypes about high-status members and perceived them as high in wealth, whereas low-status members were considered as mean and relatively poor. Positive beliefs about high-status members were more likely for high-status participants, and increased with age. This finding is in line with adolescents’ increasing understanding of the determinants of social inequalities (Flanagan et al., 2014) and structural obstacles leading to a lack of opportunities (Mistry et al., 2015).

In the case of Nepal, social inequalities are derived from the caste system, an extremely hierarchical social system that divided individuals into different social groups with different social rights, depending on the status of the specific caste in the hierarchy (Gurung et al., 2012). The caste system was deemed illegal in 1963 because it facilitated severe social, political, and economic discrimination of individuals of lower-castes (Tamang, 2014). Still, the remnants of the caste system account for Nepal’s large social inequalities, whereby caste and SES remain correlated social categories (Gurung et al., 2012). Due to this overlap of social categories (i.e., caste and SES), social mobility is restricted, social hierarchies are highly salient and individuals are easily identified by status categories.

We expect that this long history of social inequalities has had consequences for adolescents’ perceptions of social mobility, whereby they may still perceive restrictions that could be reflected in their reasoning about intergroup relations, including cross-group friendships. Accordingly, recent work from South Asian minorities living in Hong Kong suggests that adolescents not only position themselves with regards to the messages they receive from parents but also with regards to the broader social discourse about social minorities (Gu et al., 2017). Building on this work, we aimed to extend research on ERS beyond the focus on direct messages from parents and study what kind of messages adolescents perceive about social marginalization and group biases when reflecting expectations about cross-wealth friendship.

Biases Based on SES in the Context of Social Inequalities

Research has shown that stereotypes about SES are context-sensitive (Burkholder et al., 2019; Elenbaas & Killen, 2018). In academic contexts, high-SES individuals are rated higher in competence than low-SES individuals. In contrast, in social contexts, high-SES individuals are rated more negatively (i.e., selfish, cold, calculating) than are low-SES individuals (i.e., generous, honest, charitable). Moreover, how individuals are perceived based on their SES also depends on their own social status and may have consequences for perceived social mobility. High-SES adolescents may positively distinguish their own group from lower status groups (i.e., show in-group bias) and use specific social cognitions to justify their enhanced status (Nesdale, 2004; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Thus, expressing negative views about low-status individuals may be a strategy of high-status adolescents to maintain their status in the social hierarchy. In contrast, low-status adolescents may be aware of negative stereotypes about the poor; and therefore, distance themselves from being a member of this group by expressing negative views about them (Kay & Jost, 2003).

Further, a handful of studies have investigated adolescents’ perceptions of intergroup relations with regard to their own SES, whereby adolescents from higher SES backgrounds were more likely to consider the economic needs of high SES peers (Burkholder et al., 2019; Elenbaas & Killen, 2018). The current study extends this prior work by investigating whether negative perceptions of traits based on SES are extended to peer contexts and whether adolescents perceive parents as approving of cross-group friendships determined by SES.

Attitudes About Cross-Group Friendship and Parental Expectations About Friendship

Despite their positive effects, cross-group friendships are often discouraged by adults, and particularly by parents (Hitti et al. 2019; Rutland & Killen, 2015). Parents reflect an important source of authority, providing norms for intergroup-encounters (Brenick & Romano, 2016). Research on ERS suggests that parental messages offer guidance on how to manage the social system, with its social rules that determine possibilities related to social status (Hughes et al., 2006). For example, ethnic minority parents actively promote their children’s awareness of discrimination and discuss coping strategies, labeled as preparation for bias. This information becomes more salient during adolescents’ identity seeking processes and is more prominent among parents who themselves faced discrimination or believed that their children had been discriminated against by peers (Hughes & Johnson, 2001; Hughes et al., 2006). ERS research predominantly focuses on parents from racial and ethnic minority groups; however, more insights are needed regarding parents from racial and ethnic majority groups, as parents’ negative attitudes interfere with adolescents’ cross-group friendship (Scott et al., 2020). Racial and ethnic majority parents often convey stereotypes and negative intergroup attitudes to their children, whereby adolescents from high-status groups are more similar to their parents with regards to negative intergroup attitudes as compared to adolescents from low-status groups (Degner & Dalege, 2013). Consequently, research on how adolescents perceive parental expectations about status and mobility is warranted.

Yet, research on how adolescents’ reason about parental messages regarding cross-group friendship is rare. A recent article has called for more research on how parents transmit biases to children (Scott et al., 2020). One of the few studies on adolescents’ perceptions of parental biases shows that adolescents are highly aware of parent biases regarding cross-ethnic relationships (Edmonds & Killen, 2009). This tendency to expect in-group parents to have prejudicial attitudes towards cross-ethnic peers increases from mid to late adolescence (Brenick & Romano, 2016; Hitti, et al. 2019).

The Present Study and Hypotheses

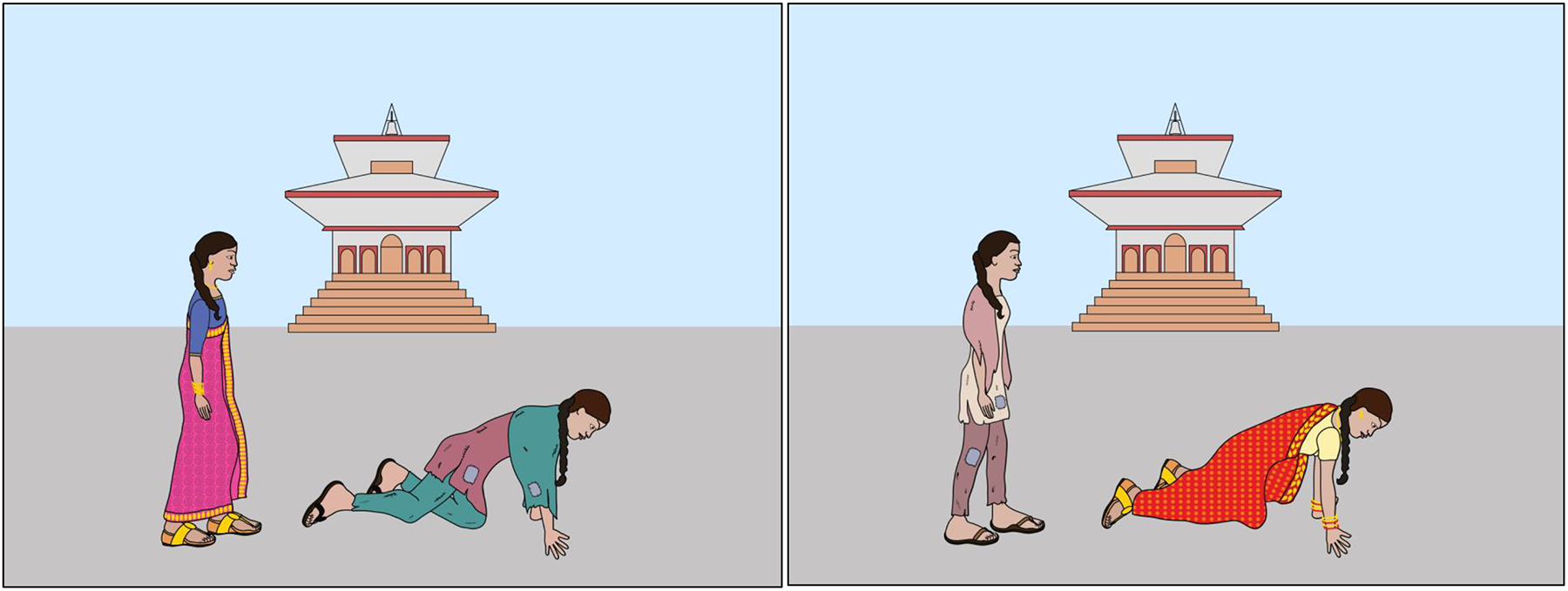

The goal of this study was to investigate parental expectations regarding cross-group friendships in the context of strong inequalities, in order to better understand the perspective of parents as socialization agents in marginalized groups. Specifically, we studied how adolescents interpret the intentions of high- and low-SES peers in a dyadic encounter, whether they view the dyad as having the potential to be friends, and whether the high- and low-SES parent of each peer would want them to be friends. We administered the Ambiguous Situations Task (AST) in which adolescents either viewed an intergroup encounter in which the high-status target had an opportunity to help a low-status peer or viewed a version, in which the roles were reversed; the low-status target had an opportunity to help the other peer (see Figure 1). This task has been used previously to provide a measure of whether individuals attribute intentions differentially based on group membership such as race in the U.S. (McGlothlin & Killen, 2006, 2010), and was modified for use in Nepal through focus groups and pilot testing with Nepalese adolescents (see supplementary files for details).

Figure 1. Ambiguous Situation Task.

Note. The left figure displays a high-SES target as potential transgressor and low-SES target as potential victim and the right figure displays a low-SES target as potential transgressor and high-SES target as potential victim (girls’ version, for the boy’s version please see the supplementary file Figure S1). © Joan Tycko, Illustrator.

Attribution of Intention

The Attribution of Intention assessment consisted of measuring whether participants attributed neutral/positive or negative intentions to a target in a peer dyadic encounter. In line with prior research on adolescents’ negative perceptions of high wealth peers in social situations (Burkholder et al., 2019; Elenbaas & Killen, 2018), we expected that adolescents would have more negative attributions regarding high-SES than low-SES peers (H1a). Moreover, we hypothesized that older adolescents (i.e., in higher grades) would attribute more negative intentions about intergroup encounters based on SES than would younger adolescents (H1b). This expectation was due to findings that throughout adolescence, social and cultural identities and associated group norms become more salient (Killen et al., 2016). If adolescents more strongly identify with their in-groups, in-group bias increases (Nesdale, 2004; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). The increasing understanding of SES, associated social roles, and the complexities of social conventions and social traditions (Mistry et al., 2015; Rogers, 2019) may render SES as a more salient source of identification in older adolescents. Lastly, since higher status groups may express higher in-group bias (Dunham et al., 2014), we expected that high-SES, compared to low-SES, participants would have more positive expectations about high-SES peers (H1c).

Perceived Friendship

Based on previous findings about adolescents’ awareness of social hierarchies (e.g., Dunham et al., 2014; Mistry et al., 2015), we hypothesized that adolescents would not expect that friendships between high- and low-SES peers was feasible which would be reflected in their reasoning about social hierarchies (H2a). We also hypothesized that older adolescents (i.e., in higher grades) would be more pessimistic about friendship than would younger adolescents (H2b) and for adolescents with high as compared to low SES (H2c), which would be reflected in their reasoning about social hierarchies.

Parental Expectations About Friendship

Based on previous findings (e.g., Degner & Dalege, 2013; Edmonds & Killen, 2009), we expected that parental expectations about friendship would vary depending on whether the parents were high- or low-SES, with more negativity related to high-SES parents based on reasoning reflecting conceptions of reputation and social hierarchies, and more positivity related to low-SES parents because of perceived opportunities for social mobility (H3a). Lastly, we assumed that older adolescents in higher grades (H3b) and high SES participants (H3c) would be more negative about parental expectations of high SES parents and be more likely to justify these negative parental expectations based on reputational concerns than would younger adolescents and low-SES participants.

Method

Participants, Region, and Procedure

This project was approved by the human subjects board of the University of Zurich (Project Name: Social Development and Social Change in Nepal, Protocol Nr. 18.12.8). The sample consisted of 389 early adolescents (53% girls) attending grades seven (Mage = 12.88; SDage = 0.77; n = 99), eight (Mage = 13.52; SDage = 0.77; n = 91), nine (Mage = 14.65; SDage = 0.86; n = 102) and ten (Mage = 15.26; SDage = 0.61; n = 97). Since some adolescents did not have birth certificates and roughly estimated their age, we used grade as our developmental and socialization marker given the students’ shared social experiences by grade. Participants attended schools in a remote area in the Kathmandu valley, a region characterized by large social inequalities (Central Bureau of Statistics Nepal, 2011).

Students’ SES was measured using items about housing and property from a representative statistical report on social and economic development in Nepal (CBS, 2011). Based on the data from this representative report, the predictive value of each of these indicators for the real per capita consumption was calculated and used to estimate the real per capita consumption (RPC) for each student in the current sample (for details, see supplemental materials S0). About half of the sample (53%) were Hindu, 43% belonged to a mixture of other Nepalese ethnic backgrounds with different primary languages and customs, and 4% were Dalit (from the lowest status castes).

Individually administered interviews were conducted by local research assistants. The average duration for the administration of the AST was 20 minutes. Active parental consent was obtained for all participants (for illiterate parents, 16% of fathers, 35% of mothers, and 22% of other primary caregivers, research assistants served as witnesses). Seven students (2%) were not included in the final sample since their primary caregivers refused their consent. In addition, adolescent assent was requested and adolescents had the opportunity to terminate the interview at any time (all adolescents completed the session). A subset of the research assistants (fluent in English and Nepalese) translated the interview data from Nepalese to English which was reviewed by the research coordinator.

Ambiguous Situations Task

The AST (McGlothlin et al., 2006; Killen et al., 2010) involves displaying pictures to students that depict a dyadic peer encounter (see Figure 1), whereby participants evaluate whether an individual is helping or hindering in a situation in which the intentions are ambiguous (e.g., did the target peer push the other one down, or will the target peer help the other one?). In this task, the social group membership of that individual is systematically varied to compare whether negative intentions are more likely attributed to the perpetrator based on group membership (for more details, see the supplementary file, S1).

For the current study, status was varied by the SES of the target, one was from a high-SES background (e.g., nice clothes) and one was from a low-SES background (e.g., old, torn clothes). Since Nepal represents a novel context for research on this topic, focus groups were conducted on adolescents’ interpretations of peer encounters to adapt the measure (for details see online appendix S1). To ensure that participants viewed the SES depictions as intended, pilot data were collected from adolescents (N = 24) unfamiliar with the purpose of the study. They rated the story protagonists on a social ladder with regard to their SES (0 = lowest end in the wealth pyramid, 10 = highest end). Since all adolescents ascribed ratings between 2–4 to the low, and 7–9 to the high SES character, we concluded that they perceived the pictures as interactions between low-and high-SES individuals. During the focus groups and the experiment, the research assistants were specifically instructed not to label the characters as low- and high-SES (or related terms). All pictures were gender-matched.

The types of dependent measures included both binary responses (yes/no) as well as reasoning data. There were seven dependent measures for this task for the three assessments (attribution of intention, perceived friendship, parental expectations about friendship): 1) Attribution of intention, adolescents explained what happened in the picture (“What do you think happened in this picture?”; coded as negative, neutral/positive, see Table 1); 2) Perceived friendship between the two story protagonists (“Do you think the two characters are friends?”; coded as no = 0, yes = 1); 3) Reasoning about perceived friendship (“Why are/aren’t they friends?”; coded as shared interests, moral concerns, or social hierarchies, see Table 1); 4) Judgments about high-SES parental expectations (“Do you think the parents of this [experimenter points to the high-SES girl/boy] want the two children to be friends?”; no = 0, yes = 1); 5) Judgments about low-SES parental expectations (“Do you think the parents of this [experimenter points to the low-SES girl/boy] want the two children to be friends?”; no = 0, yes = 1); 6 & 7) Reasoning for high- and low-SES parental expectations (“Why do you think that his/her parents want/do not want them to be friends?”; coded as moral concerns, social mobility, social hierarchies, or reputation, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Reasoning Category, Description, and Examples for Attribution of Intention, Perceived Friendship, and Parental Expectations

| Category | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Attribution of Intention | ||

| Negative | Discrimination, Physical and Relational Aggression | “This rich girl looks like she is not

letting her go into the temple.” “One rich girl is beating up a poor girl, she pushed her.” “It looks like one poor person has got sick and fell down. And it looks like the other rich person is not bothered by him.” |

| Neutral / Positive | Neutral and/or positive activities of the character | “One person is on the ground. The other

person is walking.” (neutral) “The rich girl was on her way to the temple. She was wearing high heels and fell. The poor girl helps her up.” (positive) |

| Perceived Friendship | ||

| Similarity | Emphasis on (lacking) shared interests and common experiences | “Their houses might be close by. They study in the same class and play together.” |

| Moral concerns | References to the potential harm or help to the character on the ground | “If they were friends she would not be

treating her like that. She is not supporting her.” (negative

intentions) “Because she is helping and taking good care of him.” (positive intentions) |

| Social hierarchies | Reference to social hierarchies | “He is very rich and he is poor. Their

levels don’t match up.” “One is poor and the other one is rich. Even if the rich makes poor their friend then they humiliate them a lot. That’s why poor people don’t even want to be friends with them.” |

| Parental Expectations about Friendship | ||

| Moral concerns | Equal treatment of others and other-oriented concern | “When she fell down, she was just

watching and not helping. Later on, if they become friends then she

might not help when there are problems.” “Her family says she can be friends with anyone regardless of who it is.” |

| Social mobility | Friendship as a resource for social mobility through academic, social or financial support | “Because it is a big thing to help the

poor. So that the future of the poor person is also

brighter.” “They feel if the rich become their friends they will get to learn things, their future would be bright, and the rich wouldn’t discriminate them anymore.” “If they would be friends, their daughter would be liked by all, would go to school and make a lot of rich friends wear nice clothes, and eat nice food.“ |

| Social hierarchies | Reference to social hierarchies, traditions related to hierarchies, the caste system | “Because their levels don’t

match up. You have to be friends with the people from your same level.

Those friends are able to support you when you work on something. That

is why rich people do not want their daughter to be friends with such a

poor girl.” “Rich families say that you shouldn’t be friends with such poor families because their lifestyle is different. They have certain standards. They buy expensive things and wear nice clothes.” |

| Reputation | Reference to reputation and sanctions from the social community or negative influences from being around low SES peers | “The rich family’s relatives

might be rich as well and if she takes her [low SES] to her home then

her reputation might get ruined. They believe that if you become friends

with the poor then you lose respect.” “They might think that having poor friends can make them poor.” “It is because their [high SES] son would be like him [low SES] and get bad and undisciplined.” |

Reliability Coding

The reasoning data gained from the AST were coded by a team of four trained research assistants (for details, see supplementary materials S2). The two coding categories (i.e., distinguishing between negative = 0 and positive/neutral attributions = 1) for attribution of intention were based on previous research (Dodge et al., 2015; McGlothlin et al., 2006). To develop the reasoning codes about friendship expectations, the social reasoning developmental theory (Killen et al., 2016) was used. This theory integrates social domain theory (Smetana, 2011; Turiel, 1983) and the social identity perspective, which is relevant for understanding group dynamics (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). In addition to categories developed in previous research about friendship expectations (Edmonds & Killen, 2009; McGlothlin et al., 2006), we distinguished the category reflecting intergroup dynamics to reflect differential reasoning about social mobility, social hierarchies, and reputation. These considerations were based on system justification theory (Kay & Jost, 2003) and recent work on adolescents’ reasoning about social inequalities (Elenbaas, 2019). Light’s Kappa (1971) was κ = .95 for the attribution of intention, κ = .88 for the reasoning about perceived friendship, and κ = .82 for both reasoning questions about parental expectations (κ > .80 is considered as almost perfect agreement; Hallgren, 2012).

Since SES and caste are correlated social categories in Nepal, we accounted for the possibility that adolescents may use caste or a combination of caste and SES in their interpretations of the ambiguous peer encounter and reasoning about friendship expectations. In order to control for potential culturally specific narratives about caste, we computed the number of references to caste in each of the reasoning categories. The frequency of references that were about both, caste and wealth, was very low for all dependent variables (i.e., 4–6%). The frequency of references that were only about caste, were even lower (i.e., 2–3% of all answers). Thus, adolescents predominantly interpreted the AST in terms of SES.

Data Analytic Strategy

Using well validated measures from social-cognitive development and drawing on social domain theory (Smetana, 2011; Turiel, 1983, 2014), participants’ open-ended responses were analyzed quantitatively, using several statistical methods. For each assessment, we conducted a set of analyses to answer our specific hypotheses.

To analyze attribution of intention, we conducted a generalized linear model (GLM) accounting for the binary metric of the variable. We entered the predictor variables, SES of the target (hypothesis 1a), grade and student SES (hypotheses 1b & 1c), while controlling for gender effects (identified in previous research, e.g., McGlothlin et al., 2006). In order to understand whether and how the reasoning about perceived friendship was associated with perceived friendship (hypothesis 2a), a chi-square test was performed. In detail, we created a 2 by 3 cross-table (perceived friendship: no / yes by the three types of reasoning: social hierarchies, similarities, moral concerns). Next, we analyzed whether adolescents’ perceived friendship between the two characters were different depending on their grade and SES (hypotheses 2b & 2c), while controlling for gender and the attributed intention. Since the perceived friendship variable was binary (0 = no, 1 = yes), we conducted a GLM. To analyze whether the reasoning associated with friendship expectations differed depending on adolescents’ grade and SES (hypotheses 2b & 2c), we conducted a multinomial logit model (MLM). MLM estimate the probability that one category of the dependent variable is chosen over the other, whereby a reference category is chosen, which is compared to all other categories. In order to test whether adolescents differed in their expected friendship regarding high- and low-SES parents’ expectations, we first used an Exact McNemar test. Next, similar to the analyses for perceived friendship, two chi-square tests were used to analyze the relationships between judgment and reasoning (hypothesis 3a; expected friendship: no / yes by reasons: moral concerns, social mobility, social hierarchy and reputation). In order to visualize differences between the reasoning categories and to estimate confidence intervals, two simple multinomial logit models were created with entering the parental expectation (no/yes) as predictor for differences in the reasoning categories. Lastly, to analyze our hypotheses regarding differences in reasoning about parental expectations of high SES parents by grade and student SES (hypotheses 3b & 3c), we conducted a GLM (i.e., for high-wealth parents’ expectations), followed by an MLM.

Taken together, our methodological approach considered the interrelatedness of the dependent variables, by including them as control variables for the other measures, and accounted for the different distributions of the dependent variables (i.e., binary, multinomial). Since the students were from 17 different school classes, we also considered between-group variance (i.e., differences at the classroom level). Based on using different model comparisons, differences in the variables of interest between classrooms were very small and not significant; thus, following recommendations of Bliese (2000), the use of hierarchical models was not appropriate (for details see supplemental materials S3).

Results

Attribution of Intention (AoI)

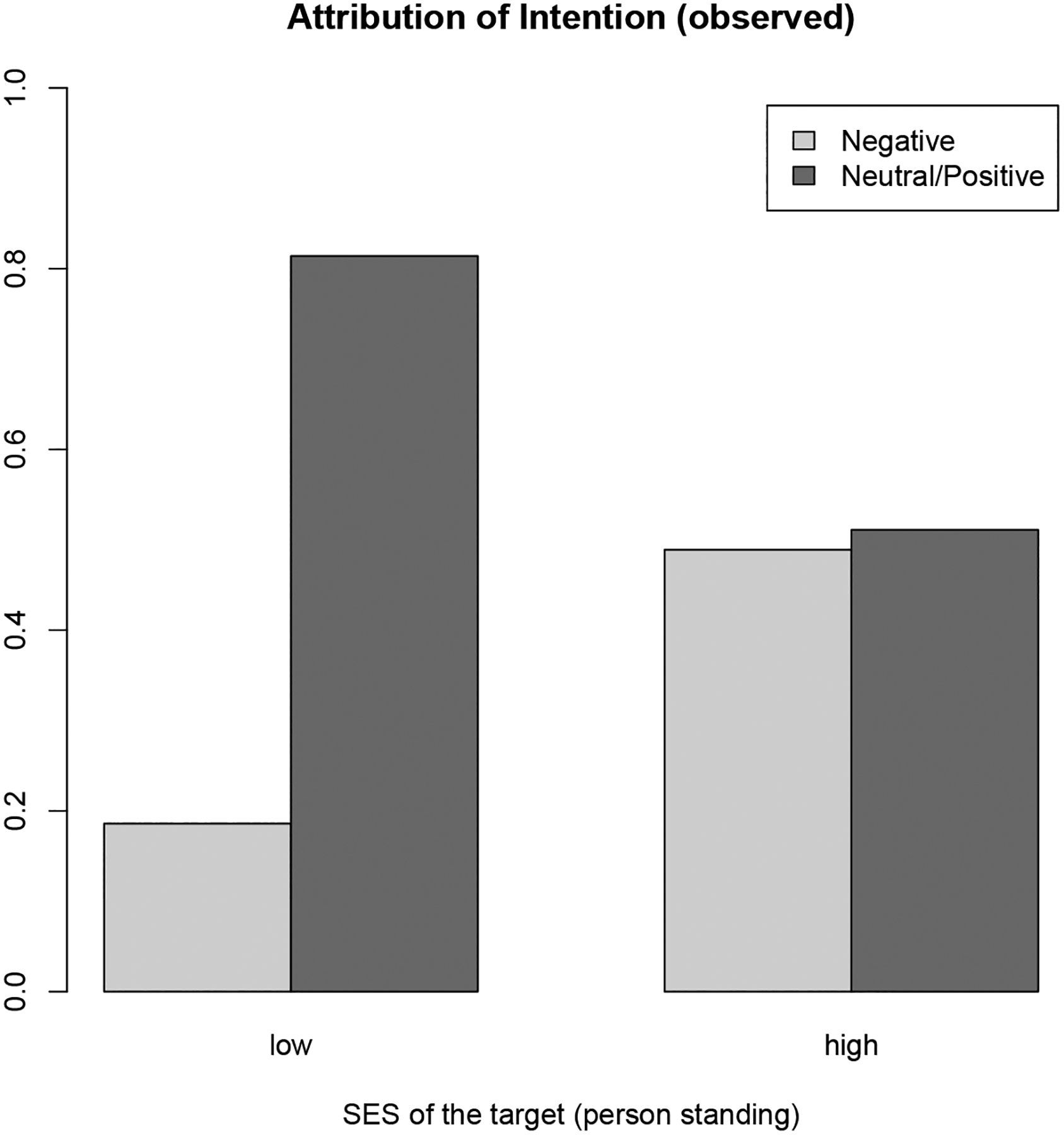

Frequencies revealed that 33% of the participants attributed negative intentions and 65% of the adolescents attributed neutral or positive intentions to the target (for examples of statements that were coded as negative or neutral/positive, see Table 1). Supporting our first hypothesis (H1a), the results from the first GLM (see Table 2, Model 1) showed that adolescents ascribed 4.65 times more neutral/positive intentions rather than negative intentions to the low-SES than to the high-SES target. The data in Figure 2 show that 81% of adolescents ascribed neutral/positive intentions to the low-SES target, while 51% of adolescents ascribed neutral/positive intentions to the high-SES target. Thus, most attributes of the scenario were positive or neutral. However, also confirming H1a, when negative attributions were present, participants were twice as likely to associate negative attributions with the high-SES rather than the low SES target (see Figure 2). In addition, and in line with our hypothesis regarding grade (H1b), adolescents in grade 10 were significantly less likely to attribute positive intentions than younger adolescents (see Table 2, Model 1). No significant differences emerged for adolescents’ own SES (H1c).

Table 2.

Results of the Generalized Linear Model Regressing Attribution of Intention (AOI), Perceived Friendship, and Parental Expectations for High-SES Parents on Student SES, Grade, and Target SES

| Model 1 Attribution of Intention | Model 2 Perceived Friendship | Model 3 Parental Expectations: High SES | |

|---|---|---|---|

| exp(coef) [95% CI] | exp(coef) [95% CI] | exp(coef) [95% CI] | |

| Sex (0 = male) | 0.40 [0.24, 0.65]*** | 1.23 [0.71, 2.16] | 1.54 [0.96, 2.53]† |

| Grade 8 vs. 7 | 0.87 [0.44, 1.70] | 1.26 [0.59, 2.69] | 1.04 [0.55, 1.97] |

| Grade 9 vs. 7 | 0.84 [0.43, 1.64] | 0.91 [0.42, 1.99] | 0.65 [0.34, 1.24] |

| Grade 10 vs. 7 | 0.50 [0.25, 0.95]* | 1.21 [0.56, 2.62] | 0.50 [0.25, 0.99]* |

| Student SES | 0.89 [0.71, 1.13] | 0.82 [0.61, 1.09] | 0.75 [0.58, 0.95]* |

| SES of target (0 = low) | 0.21 [0.13, 0.34]*** | 1.55 [0.88, 2.76] | 0.66 [0.40, 1.08] |

| Attribution of intention (0 = negative) | 1.52 [0.82, 2.92] | 1.22 [0.71, 2.13] | |

| Parental expectations for low-SES parents | 3.89 [1.90, 8.86]*** | ||

| R 2 GLM | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| χ2HL, p | 7.23, p = 0.51 | 10.13, p = 0.26 | 5.11, p = 0.75 |

Note. AOI (0 = negative, 1 = neutral/positive). The variable student SES was z-transformed. Control variables: Sex, attribution of intention (for friendship beliefs and parental expectations high SES) and parental expectations for low-SES parents (for parental expectations high-SES). We report log-odds with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for effect sizes and indicate Mc Fadden’s pseudo- R2 (Long & Freese, 2006) and Hosmer and Lemeshow’s goodness of fit test (Hosmer, Lemeshow, & Sturdivant, 2013) for model fit statistics.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001, two-tailed.

Figure 2. Observed Frequencies of the Attribution of Intention as a Function of Target SES.

Note. The y-axis reflects the percentage of how many times attributions were coded as negative respective neutral/positive (1 = 100%).

Perceived Friendship and Reasoning

In line with H2a, we found that for all adolescents, only 18% believed that the low- and high-SES story characters were friends. We analyzed the reasoning underlying adolescents’ perceived friendship (i.e., the cross-table between the reasoning categories moral concerns, similarity, and social hierarchies and answering the friendship question with yes or no) by using a chi-square test. This test revealed that students who perceived friendship as feasible used different reasons to justify their answer than students who did not, χ2(2) = 188.17, p < .001. When inspecting the total percentages of the answers in each reasoning category by friendship beliefs, it became apparent that adolescents referenced social hierarchies (37%) and moral concerns (41%) when they believed that the two characters were not friends (5% mentioned lacking similarity). Of the small proportion of adolescents who believed the two characters were friends, 4% referenced moral concerns and 13% referenced reasons of similarity (0% referenced social hierarchies). Thus, partially supporting H2a, the vast majority of adolescents referenced social hierarchies, in addition to moral reasons, when they viewed friendship as unlikely (for specific examples see Table 1).

The results from the second GLM (see Table 2, Model 2) showed that perceived friendship did not significantly vary as a function of students’ grade or student SES. In order to examine whether adolescents differed in their reasoning depending on their grade and SES, we calculated a MLM (see Table 3, Model 1). The results indicated that there were no grade-related differences in students’ social reasoning for perceived friendship, disconfirming H2b. The reasoning provided differed depending on SES, with high SES participants being more likely to reference social hierarchies over similarity than low SES participants. However, as there was no difference for friendship beliefs (i.e., yes/no), H2c was only partially supported.

Table 3.

Results of the Multinomial Logit Model on Adolescents’ Social Reasoning About Friendship and About Parental Expectations Regarding Friendship Potential Between the Low- and High-SES Story Characters

| Model 1: Perceived friendship | Model 2: High SES parents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity n = 66 | Moral concerns n = 164 | Social Mobility n = 28 | Social hierarchies n = 131 | Reputation n = 117 | |

| exp(coef) [95% CI] | exp(coef) [95% CI] | exp(coef) [95% CI] | exp(coef) [95% CI] | exp(coef) [95% CI] | |

| Sex (0 = male) | 0.77 [0.41, 1.45] | 0.74 [0.46, 1.20] | 2.56 [0.94, 6.96]† | 0.90 [0.50, 1.61] | 0.65 [0.35, 1.18] |

| Grade (0 = 7 & 8, 1 = 9 & 10) | 1.15 [0.61, 2.14] | 0.83 [0.52, 1.34] | 0.51 [0.19, 1.36] | 1.27 [0.70, 2.27] | 1.96 [1.07, 3.59]* |

| Student SES | 0.63 [0.45, 0.90]* | 0.86 [0.68, 1.08] | 0.93 [0.58, 1.51] | 1.17 [0.88, 1.57] | 1.29 [0.96, 1.74]† |

| SES of target (0 = low) | 2.45 [1.26, 4.77]** | 1.51 [0.91, 2.51] | 3.44 [1.29, 9.21]* | 1.69 [0.91, 3.15]† | 2.12 [1.11, 4.05]* |

| Attribution of Intention | 1.86 [0.87, 3.94] | 0.86 [0.50, 1.47] | 4.62 [1.20, 16.38]* | 0.82 [0.43, 1.58] | 1.33 [0.67, 2.69] |

| Difference in model deviance | 39.13 | 56.31 | |||

| Explained deviance | 0.05 | 0.06 | |||

Note. Reference category for perceived friendship: Social hierarchies (n = 132). Reference category for parental expectations about high SES parents: Moral concerns (n = 79). The exponentiated coefficients of the MLM models express the ratio of choosing the other reasoning categories over the reference category for an increase of one unit in the predictor variable. For example, students in grades 9 & 10 have a 1.96 times higher chance of referencing reputation over moral concerns compared to students in grades 7 & 8.

In order to increase statistical power, lower and higher grades were combined. The variable student SES was z-transformed. Control variables: Sex, SES of the target, and attribution of intention. We report log-odds with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for effect sizes and indicate the model deviance of the final model as compared to the model deviance of the null model for model fit statistics and the explained deviance (see Guisan & Zimmermann, 2000).

< .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001, two-tailed.

Parental Expectations About Friendship and Reasoning

To compare whether adolescents differed in their answer patterns regarding high- and low-SES parents’ expectations, we used an Exact McNemar test with central confidence intervals (Fay, 2018), which was significant χ2(1) = 180.66, p < 0.001, odds ratio = 0.04[CI95 = 0.02, 0.08], Φ = 0.18. In line with H3a, 81% of adolescents thought that the low SES parents would want the two story characters to be friends, while only 30% of the adolescents reported that the high SES parents would approve of that friendship.

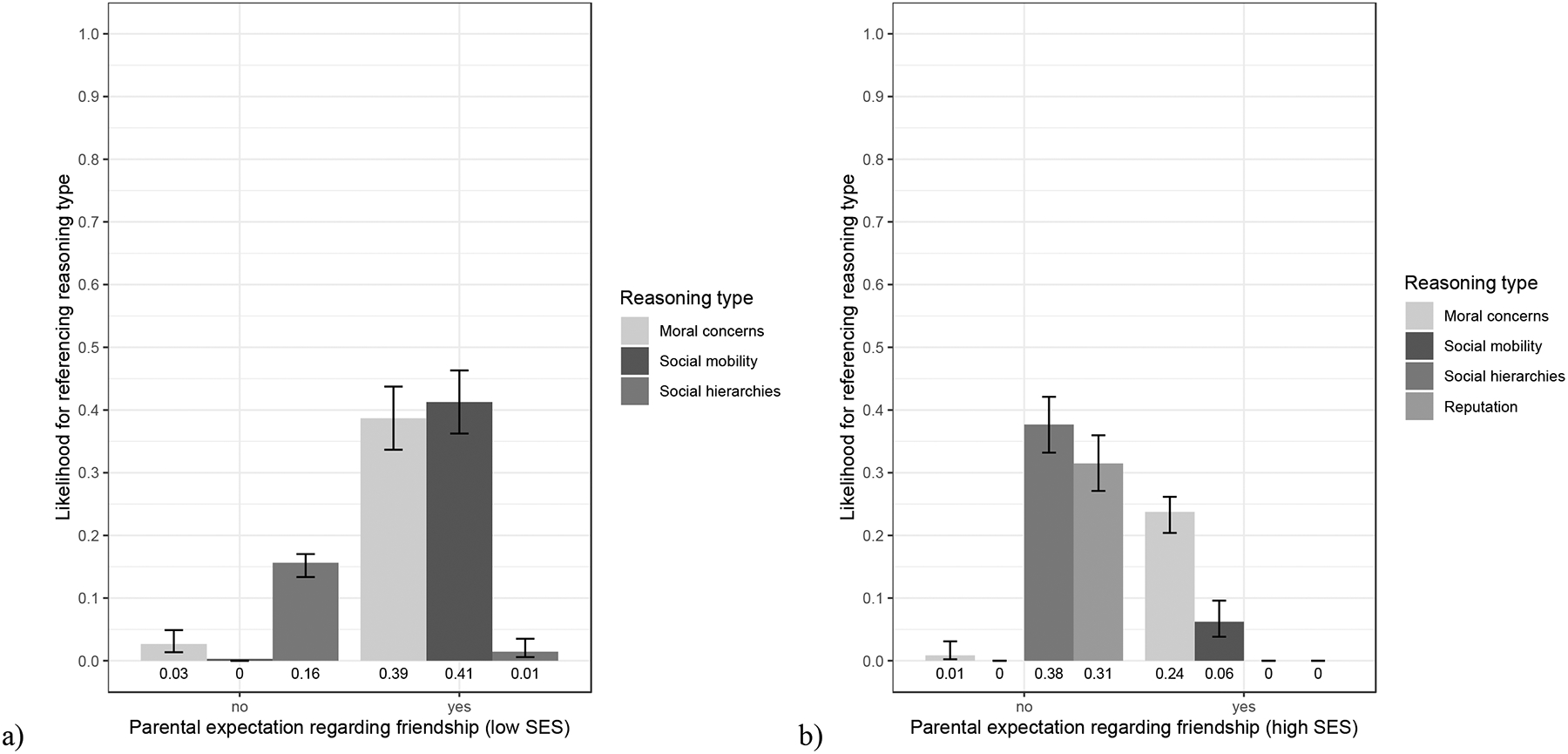

Reasoning About Low SES Parents’ Friendship Expectations

A chi-square test revealed that adolescents who perceived that low SES parents would approve of the friendship used different reasons to justify their answer than students who did not, χ2(2) = 245.85, p < .001. The expected likelihood for the reasons that adolescents used to justify parental expectations and their 95% confidence intervals are displayed in Figure 3a (for examples, see Table 1). Supporting H3a, adolescents were more likely to use reasons of social mobility (in addition to other-oriented concern) when they believed that low-SES parents wanted the story characters to be friends (see Figure 3a). Since there was almost an absolute difference in comparing the likelihood of choosing moral concerns respective social mobility to the likelihood of social hierarchies, no statistical follow-up tests were conducted. Figure 3a also shows that the likelihood of choosing reasons of social hierarchies was significantly higher than moral concerns for negative parental expectations.

Figure 3. Estimated Values for Adolescents’ Reasoning About Parental Expectations Regarding Friendship Between the Two Story Characters, for the Parents of the a) Low-SES and b) High-SES Targets.

Note. The bars display transformed log-odds of the likelihood of referencing a specific reasoning type with 95% confidence intervals. The values have been estimated based on a multinomial-logit model for low and for high SES parents respectively. The number below each bar reflects percentage of the specific category with regard to the total answers provided (whereby all categories together add up to 100%).

Reasoning About High SES Parents’ Friendship Expectations

A chi-square test revealed that adolescents who perceived that high SES parents would approve of the friendship used different reasons to justify their answer than students who did not, χ2(3) = 332.11, p < .001. Further supporting H3a, Figure 3b (i.e., the expected likelihood for the reasons that adolescents used to justify parental expectations and their 95% confidence intervals) shows that adolescents expected that high-SES parents would not approve of the friendship because of reasons of social hierarchies and reputation. Since the results showed an absolute difference between using reasons about reputation and hierarchies over moral concerns to justify negative parental expectations, no statistical follow-up tests were required. Figure 3b also shows that adolescents justified positive parental expectations for high-SES parents with predominantly moral concerns.

The Role of Participant SES and Grade for Parental Expectations and Reasoning

To test the role of SES and grade for parental expectations, we first conducted a GLM to investigate differences with regards to parental expectations, followed by a MLM to analyze the reasoning provided to justify parental expectations. Supporting our expectations (H3b & H3c), older adolescents in grade 10 (log odds[95% CI] = 0.50 [0.25, 0.99]) and participants with higher SES backgrounds (log odds[95% CI] = 0.75 [0.58, 0.95]) were significantly more pessimistic regarding parental approval for cross-group friendship than younger adolescents in grade 7 and participants with lower SES (see Table 2, Model 3). Further supporting hypothesis H3b, the findings from the MLM model (see Table 3, Model 2) revealed that older adolescents in grades 9 and 10 (log odds[95% CI] = 1.96 [1.07, 3.59]) were more likely to reference reasons of reputational concerns than younger adolescents. A similar tendency was found for SES, whereby participants with higher SES backgrounds (log odds[95% CI] = 1.29 [0.96, 1.74]) were more likely to mention reputational concerns. However, as this difference was not statistically significant, H3c was not supported. As we did not have specific hypotheses concerning adolescents’ reasoning about low SES parental expectations, these findings are reported in the supplementary file (see Tables S2 and S3).

Explorative Post-Hoc Analyses Regarding the Role of Parental Expectations

As we were interested to understand how parental expectations about low- and high-SES parents were connected, we conducted explorative post-hoc analyses. When looking at a cross-table of both parental expectations, it became apparent that 98% of the adolescents displayed one of three different expectation patterns: they either perceived that both parents would not approve of the friendship (16%), both parents would want the friendship (28%) or that the low-SES parents would want the friendship and the high-SES parents would not approve (54%). Thus, we analyzed whether these answer patterns regarding parental expectations were also associated with answer patterns in adolescents’ reasoning about parental expectations. When adolescents believed that both parents of the story protagonists were against the friendship, they most likely referenced reasons about social hierarchies for both parents (and in addition reputation for high SES parents). When they believed that both parents would approve, they were most likely to references moral concerns, followed by social mobility reasons for both parents. When they believed that the low-SES parents would want the friendship, but high-SES parents would not approve, they mostly referenced social mobility, followed by moral concerns for low SES parents and reasons of social hierarchies and reputation for high SES parents. Statistically, the likelihood of referencing specific categories when belonging to one of the three answer patterns for parental expectations, was significant for reasoning about low SES parents, χ2(4) = 256.70, p < .001, and reasoning about high SES parents, χ2(6) =307.72, p < .001 (detailed frequencies can be found in Table S4 in the supplementary file). Since there were very clear patterns and we did not have specific hypotheses regarding how the reasonings would differ in these categories, we did not conduct follow-up tests. Taken together, the exploratory post-hoc analyses suggest that adolescents’ expectations about whether low and high SES parents would approve of cross-SES friendship were related to their differentiated beliefs about social mobility and social hierarchies.

Discussion

The novel findings of this study were that adolescents living in Nepal, a society defined by strong societal inequalities and hierarchies in which low SES groups are at high risk of marginalization, expressed an awareness of the structural barriers. These barriers reflected obstacles to social mobility, expressed by pessimistic views about cross-SES friendships (82% were pessimistic) and about parental expectations regarding friendship. When asked about their expectations that high-SES parents would support cross-SES friendships, most adolescents (70%) were negative and explained this on the basis of expectations about high-SES parents’ concerns about social hierarchies (“Because their levels don’t match up. You have to be friends with the people from your same level. Those friends are able to support you when you work on something. That is why rich people do not want their daughter to be friends with such a poor girl.”) and reputational concerns, whereby breaking the norms inherent in the socially hierarchical system would lead to downward mobility (“The rich family’s relatives might be rich as well and if she takes her [low SES] to her home then her reputation might get ruined. They believe that if you become friends with the poor then you lose respect”). This pattern was stronger for older adolescents and adolescents from high SES backgrounds as compared to younger adolescents, and those from low SES families.

In contrast, most adolescents expected that low SES parents would want the friendship to exist, and partly due to the opportunity for upward mobility (“They feel if the rich become their friends they will get to learn things, their future would be bright, and the rich wouldn’t discriminate them anymore.”), and moral concerns about equal treatment of others (“Her family says she can be friends with anyone regardless of who it is.”). For those 19% of adolescents who expressed negative expectations of low-SES parents, most of the participants mentioned social hierarchies with the rationale to avoid discrimination (“Even if her [low SES] parents tell her to become friends with her, her [high SES] parents will not accept her as her friend and neither will they allow her inside their house.”).

Moreover, when analyzed together, three patterns emerged that were clearly associated with different reasoning patterns: both parents would disapprove, 16%; both parents would approve, 28%; and the low SES parents would want the friendship and the high-SES parents not, 54%. More than half of all adolescents believed that low SES parents would want the cross-group friendship predominantly for reasons of social mobility (and moral concerns), while the high-SES parents would be pessimistic because of social hierarchies and concerns about reputation. If adolescents were positive about both parents, they expressed beliefs about social mobility and moral concerns, while the minority of adolescents (i.e., 16%) was pessimistic about both parents, voicing predominantly social hierarchies (and reputation for high-SES parents). These patterns additionally highlight how reasoning about parental expectations regarding cross-group friendship reflected their understanding of the societal system, with restrictions on social relationships on one hand and beliefs about social mobility on the other hand.

The current study extends previous research on ERS in the U.S. which has focused on parental socialization strategies that prepare their children for bias and discrimination. In the current study, it was also demonstrated that adolescents received messages about the obstacles to social mobility regarding SES, and the barriers for cross-SES friendships as expressed by parents and particularly by high SES parents. Given that SES diversity exists within and between racial and ethnic groups in most countries, it may be helpful for ERS research to examine how adolescents (from both racial and ethnic minority and majority backgrounds) perceive parental support for cross-SES friendships. What messages, if any, do adolescents receive from their parents that contribute to their marginalization, opportunities for social mobility and the barriers that exist to it?

Thus, the concept of limited social mobility may be a future avenue to investigate and integrate in the multidimensional measurement of ERS. Similar concepts were previously identified as part of the construct “racial barrier awareness”, for example in the adolescent racial socialization scale (Brown & Krishnakumar, 2007). Moreover, research has yielded inconsistent findings on the associations between racial barrier socialization and adolescent adjustment (Cooper & McLyod, 2011). Thus, future research on how parental socialization messages vary among different marginalized groups could shed light, not on the multidimensionality of this construct, but also on the implications for adolescent development.

When further considering previously identified strategies that parents use for educating their children about intergroup relations (Hughes et al., 2006), we identified reasoning that reflected egalitarianism (i.e., no-one should be discriminated, everybody should have the same chances in life) in adolescents’ moral considerations. In addition, some adolescents mentioned that low-SES parents would disapprove of cross-group friendship because the high-SES parents would hurt the low-SES character (emotionally or physically). In contrast to the traditional approach of investigating ERS, which focuses on the parents’ perspective, we examined adolescents’ perspectives. Moreover, we investigated adolescents’ perspectives for SES, which is different from race and ethnicity. We propose that the novel findings of this study have implications for ERS research, such as investigating how social and ethnic minority and majority adolescents in different cultural contexts perceive parental messages, and the extent that it varies by the social group membership.

Interestingly, in this study, adolescents’ reasoning revealed their different interpretations of parental messages, depending on the parents’ social status. This resonates with recent work from Hong Kong, where Asian minority groups chose between using different languages (i.e., their native vs. the host language), depending on whether their interaction partners belonged to social minority or social majority groups (Gu et al., 2017). In order to justify their choices, they voiced parental expectations about cross-group interactions as well as negative societal perceptions about social minority groups living in Hong Kong.

Adolescents’ Reasoning about and Evaluations of Societal Inequalities in Nepal

Most Nepalese adolescents recognized the structural barriers that exist, and reasoned about the inequalities that created these constraints. These findings challenge past theories which claimed that individuals living in rigidly structured societies accepted the social structure as part of their interpersonal obligation and would not consider challenging the system out of a duty-bound obligation to uphold societal norms (see Wainryb & Rechia, 2014; Turiel, 2014, for a discussion). Thus, adolescents’ reasoning did not simply mirror the perceived societal restrictions but included negative evaluations of societal inequalities.

Adolescents in this study were very aware of the lack of opportunities for social mobility and explicitly stated that they viewed it as unfair (“In our society, there is a practice of discrimination between rich and poor. I really don’t like this because all humans are equal. If discrimination prevails, our country cannot develop and will go down.”). This research extends recent literature that has focused on children’s conceptions of social class and their perceptions of individuals from different social class backgrounds (e.g., Ghavami & Mistry, 2019) by demonstrating consequences of such beliefs for intergroup attitudes and behaviors (Ruck et al., 2019). Evidence from system justification theory suggests that stereotypes about the rich and poor can serve to justify the existing social order (Arsenio & Willems, 2017).

In the current study, the pattern of results was different since adolescents were more likely to attribute negative intentions to the high-SES target; more than half of adolescents who saw the high-SES peer as a potential transgressor voiced negative expectations (e.g., “He is discriminating him.”). In contrast, most adolescents who witnessed the low SES character in the role of a potential transgressor voiced positive or neutral views (e.g., “She is going to help the person on the ground.”). This lack of negative attributions of intentions towards the low-SES target was interesting in light of recent findings that U.S. children and adolescents’ express preferences for individuals who are paired with high-wealth cues and evaluate high-SES individuals more positively than low SES individuals (Mistry et al., 2015; Sigelman, 2012). With regards to the present study, negative perceptions of high SES individuals in social contexts could be more of a reflection that social hierarchies contradict principles of fairness and equality (“It is not rational to discriminate her because she is in tattered clothes. Some people consider themselves superior because of their money. She [high SES character] should consider her [low SES character] a human like herself.”).

We infer, based on the findings, that adolescents’ preferences for high-wealth over low-wealth peers reflect their understanding of status hierarchies, their beliefs about social mobility, and their desire for upward social mobility rather than negative attitudes about peers from low-income backgrounds. Accordingly, a recent study by Mistry and colleagues (2015) showed slightly higher positive evaluations for rich-and middle-class individuals as compared to poor individuals, but negative attitudes were only minimally higher for poor than for middle class and rich individuals. Therefore, when adolescents express more positive beliefs about social mobility, their positive aspirations could be reflected in positive evaluations of high SES individuals. This tendency to perceive chances for social mobility could account for the vastly positive evaluations of high-wealth individuals found in U.S. samples. Compared to European countries, U.S. adolescents are more likely to underestimate actual economic inequality and focus on opportunities for social mobility (Arsenio, 2018; Niehues, 2014).

The findings reported here need to be interpreted with regards to the context of this study. In Nepal, adolescents witness oppression and exclusion of marginalized youth, whereby low-wealth members experience dire living conditions in contrast to high-wealth individuals. This observation, alone, does not account for the negative intentions ascribed to the high SES story characters, however, as many high-income individuals who observe low-income living conditions often justify it with negative trait attributes (“they must be lazy”). In the present study in which adolescents voiced expectations that the high-status individual would cause harm to the low SES individual by not helping or discriminating against the low-status individual the reasoning was not about trait attributions such as “lazy” but focused on the social structure (see Table 1 for examples). Extending this recent work with a sample of Nepalese adolescents growing up in similar contexts (i.e., characterized by prejudice and experienced injustice), the current study shows that adolescents acknowledged the connection between prejudice and economic inequality and deemed it as unfair (“It is extremely not okay because in our society, even today, there is a practice of discrimination. A number of people have been affected due to this practice.”). Similar patterns may exist in different cultural contexts, where the discrimination of marginalized youth, such as ethnic and racial minority groups, renders these youth among the poorest of the country, whereby systemic biases exist that do not allow for social mobility. There is evidence from other countries that higher levels of perceived wealth inequality correlate with more negative evaluations of the society and greater preferences for redistributing resources (Arsenio, 2018; Flanagan & Kornbluh, 2019; Niehues, 2014). Further understanding adolescents’ voices from different social contexts characterized by inequalities is an important avenue for future research.

Age and SES Differences Regarding Societal Restrictions for Cross-Group Friendship

A novel finding of this research was that older adolescents were more likely to attribute negative intentions to the dyadic peer encounter based on SES and more likely to justify negative parental expectations for high-SES parents with reputational concerns than were younger adolescents. According to the idea that negative perceptions of the high SES character in the social context might reflect adolescents’ considerations and negative evaluations of social hierarchies, this age difference could be due to more differentiated social-cognitive skills and a more detailed understanding of the social context. Research has shown that older adolescents have more cognitive capacity to understand the abstract concepts related to societal inequalities (Ruck et al., 2019). In addition, they provide more complex explanations for poverty, including a combination of structural and individual attributions, acknowledging systemic causes of societal inequalities (Flanagan et al., 2014). Moreover, older adolescents’ reasoning about societal inequalities reflects not only the understanding of social conventions and traditions, which increases with age (Mistry et al., 2015), but the coordination of these aspects with moral concerns related to equality (Arsenio & Willems, 2017; Killen & Rutland, 2011). Adolescents in this study evaluated social hierarchies negatively due to concepts of equality. However, at the same time, they became increasingly concerned with reputational aspects of crossing group boundaries and increasingly acknowledged the risk of downward mobility for their families. This finding resonates with prior work showing that older adolescents increasingly integrate nonmoral concerns and contextual factors (Arsenio & Willems, 2017) when reasoning about societal issues.

The current study specifically extends this prior knowledge by showing that such principles are applied to the context of peer relations, with increasing acknowledgment of the restrictions on friendship selection. This is particularly important, since with the transition to young adulthood, these restrictions could extend to areas beyond friendship selection, such as marriage and occupation and increasingly limit opportunities for social mobility. Therefore, for older adolescents who are close to this transition, knowledge related to status and hierarchies becomes increasingly important. In addition, the potential role of parents as socialization agents limiting or approving cross-SES relationships becomes more powerful during this developmental period, which provides an area for future research.

Similar to adolescents in higher grades, adolescents with higher SES in this study were more likely to reference social hierarchies as barriers to cross-group friendship, were less optimistic regarding parental expectations of high SES parents, and more likely (although not significantly different from low SES adolescents) to refer to reputational concerns to justify these negative expectations for cross-friendship. Therefore, high-status adolescents growing up in deterministic social structures may be more likely to see their social interactions as determined by the social system than low status adolescents, since breaking these social conventions (by having cross-group friends) may have downward negative consequences for their own and their family’s social status (“She is a person from a higher level. If she [high SES] hangs out with her [low SES] then people would say bad things.”).

Moreover, considering that adolescents’ reasoning reflects messages received by parents and society, the finding is also in line with previous work from U.S. and European samples, whereby children from high-status groups reported more negative intergroup attitudes when their parents also were negative about intergroup attitudes, as compared to low-status children and their parents (Degner & Dalege, 2013). Future research should clarify the mechanisms by which adolescents learn about power inequalities through socialization.

Limitations and Future Directions

In the current work, the majority of adolescents did not expect that the two characters could be friends. This was based on the ambiguous encounter of helping or hindering a peer. These findings reflected adolescents’ pessimistic views regarding the social system (e.g., “Because most people do not become friends with the poor and people discriminate them in the society. If they would be friends, their daughter would be liked by all, would go to school, wear nice clothes, and eat nice food.”). Yet, this was only one context, and it would be fruitful for future research to examine adolescents’ expectations for cross-SES friendships in other contexts at school or at home. What contexts might it be more feasible and why? In contrast to parental expectations, friendship expectations were not differentiated by low- or high SES of the participant. Thus, examining these judgments in a range of social contexts would provide a fuller picture of expectations for cross-group friendship.

Future research could also measure whether adolescents themselves would want to be friends with low- or high-SES students, that is, their own desire for cross-group friendship or their actual cross-group friendship. To fully understand how cross-group friendships emerge in societies with strong social inequalities, a combined approach of adolescents’ expectations, own desire for friendship and social network data on their realized friendships would provide much needed information regarding the role of SES in adolescent development. By using this approach, peer influences on adolescents’ developing understanding of societal inequalities could be investigated in addition to parental socialization. Thus, it would be beneficial to obtain parental data about their attitudes and expectations for cross-SES friendships for their adolescents. While the current study investigated adolescents’ understanding of parental socialization, it did not directly measure parental socialization. Thus, future research could investigate, from a longitudinal perspective, whether adolescents’ expectations about low and high SES parental expectations predict their own friendship choices.

Moreover, with regard to the methodological approach, future research could further establish generalizability of the AST across different ecological contexts. A recent study investigating children’s hostile attribution biases in 12 ecological contexts, including countries from African, American, Asian, European regions and the Middle East found reliable results (Dodge et al., 2015). Lastly, since the current study included multiple dependent measures, we adjusted the p-values hypotheses-wise (for details see the supplementary file, S5). Thereby, the effects regarding students’ SES remained significant, while the effects regarding grade differences became non-significant (all below p < .10). Future research should thus replicate these findings with more power to detect small effects.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

Taking a developmental science approach, this study investigated how adolescents living in a country with a long history of societal and structural inequalities, conceptualized obstacles to social equality. While the awareness of specific social barriers increased with age, most adolescents were critical, referring to moral concerns about the benefits of social equality. Adolescents explicitly reflected on their awareness of the social barriers due to social hierarchies, and the negative consequences for social inclusion.

Moreover, this study provided new data outside North America and Europe that shed light on adolescents’ perceptions of parental messages about peer friendships that cross SES boundaries (high and low SES), and how these perceptions reveal adolescents’ views about social hierarchies and reputation. These insights from Nepal provide new research questions given that SES biases exist in North America and Europe regarding upward mobility. For example, dramatic variability exists regarding SES in the U.S. (Smeeding, 2016), yet, very little is known about whether adolescents perceive SES as a barrier for friendship.

With more research in multiple societal contexts, these findings contribute to social science policy research on how to improve the situation of adolescents from less advantaged social backgrounds (Arsenio, 2018). An important factor to consider are adolescents’ perceptions about familial expectations. The current study highlights how such perceptions capture perceptions of the social system, with the awareness of how cross-group friendships might negatively affect social mobility. Therefore, policies aiming to improve intergroup relations need to consider the central messages that adolescents perceive and target their sources. Thus, a systemic approach that fosters positive messages about intergroup relations, including the family environment is encouraged, specifically as opportunities for cross-group friendships are a powerful way to create inclusive societies (Turner & Cameron, 2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The last author was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, R01HD093698.

Contributor Information

Jeanine Grütter, Jacobs Center for Productive Youth Development, Universität Zürich.

Sandesh Dhakal, Tribhuvan University, Nepal.

Melanie Killen, University of Maryland.

References

- Arsenio W (2018). The wealth of nations: International judgments regarding actual and ideal resource distributions. Current Directions in Psychological Science. Advance online publication. 10.1177/0963721418762377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenio WF, & Willems C (2017). Adolescents’ conceptions of national wealth distribution: Connections with perceived societal fairness and academic plans. Developmental Psychology, 53, 463–74. 10.1037/dev0000263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliese PD (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Klein KJ & Kozlowski SW (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TL, & Krishnakumar A (2007). Development and validation of the Adolescent Racial and Ethnic Socialization Scale (ARESS) in African American families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 1072–1085. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9197-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brenick A, & Romano K (2016). Perceived peer and parent outgroup norms, cultural identity, and adolescents’ reasoning about peer intergroup exclusion. Child Development, 87, 1392–1408. 10.1111/cdev.12594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder AR, Elenbaas L, & Killen M (2019). Children’s evaluations of intergroup exclusion in interracial and inter-wealth peer contexts. Child Development. 10.1111/cdev.13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causadias JM, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2018). Reframing marginalization and youth development: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist, 73, 707–712. 10.1037/amp0000336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics Nepal [CBS] (2011). National Living Standard Survey.

- Cooper SM, & McLoyd VC (2011). Racial barrier socialization and the well-being of African American adolescents: The moderating role of mother–adolescent relationship quality. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 895–903. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00749.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner J, & Dalege J. (2013). The apple does not fall far from the tree, or does it? A meta-analysis of parent-child similarity in intergroup attitudes. Psychological Bulletin, 139, 1270–1304. 10.1037/a0031436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone PS, Lansford JE, Sorbring E, Skinner AT, Tapanya S, … Pastorelli C (2015). Hostile attributional bias and aggressive behavior in global context. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 9310–9315. 10.1073/pnas.1418572112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, & Murnane RJ (2014). Restoring opportunity: The crisis of inequality and the challenge for American education. Harvard Education Press and the Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Y, Srinivasan M, Dotsch R, & Barner D (2014). Religion insulates ingroup evaluations: The development of intergroup attitudes in India. Developmental Science, 17, 311–319. 10.1111/desc.12105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds C, & Killen M (2009). Do adolescents’ perceptions of parental racial attitudes relate to their intergroup contact and cross-race relationships? Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 12, 5–21. 10.1177/1368430208098773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L (2019). Perceptions of economic inequality are related to children’s judgments about access to opportunities. Developmental Psychology, 55, 471–481. 10.1037/dev0000550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L, & Killen M (2018). Children’s perceptions of economic groups in a context of limited access to opportunities. Child Development, 90, 1632–1649. 10.1111/cdev.13024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay MP, (2018). exact2×2: Exact conditional tests and matching confidence intervals for 2 by 2 tables. ftp://ftp2.de.freebsd.org/pub/misc/cran/web/packages/exact2×2/vignettes/exact2×2.pdf

- Flanagan CA, & Kornbluh M (2019). How unequal is the United States? Adolescents’ images of social stratification. Child Development, 90, 957–969. 10.1111/cdev.12954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan CA, Kim T, Pykett A, Finlay A, Gallay EE, & Pancer M (2014). Adolescents’ theories about economic inequality: Why are some people poor while others are rich? Developmental Psychology, 50, 2512–2525. 10.1037/a0037934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu MM, Mak B, & Qu X (2017). Ethnic minority students from South Asia in Hong Kong: Language ideologies and discursive identity construction. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 37, 360–374. 10.1080/02188791.2017.1296814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung Y, Suwal BR, Pradhan MS, & Tamang MS (2012). Nepal Social Inclusion Survey. Caste, ethnic, and gender dimensions of socio-economic development, governance, and social solidarity. Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology, Tribhuvan University. [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami N, & Mistry RS (2019). Urban ethnically diverse adolescents’ perceptions of social class at the intersection of race, gender, and sexual orientation. Developmental Psychology, 55, 457–470. 10.1037/dev0000572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren KA (2012). Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 8, 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitti A, Elenbaas L, Noh J, Rizzo MT, Cooley S, & Killen M (2019). Expectations for cross-ethnic inclusion by Asian American children and adolescents. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. Advance online publication. 10.1177/1368430219851854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW Jr., Lemeshow SA, & Sturdivant RX (2013). Applied Logistic Regression. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, & Johnson DJ (2001). Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63, 981–995. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00981.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 747–770. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AC, & Jost JT (2003). Complementary justice: Effects of “poor but happy” and “poor but honest” stereotype exemplars on system justification and implicit activation of the justice motive. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 823–837. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Elenbaas L, & Rutland A (2016). Balancing the fair treatment of others while preserving group identity and autonomy. Human Development, 58, 253–272. 10.1159/000444151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, & Rutland A (2011). Children and social exclusion: Morality, prejudice, and group identity. Wiley/Blackwell Publishers. 10.1002/9781444396317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Kelly MC, Richardson C, & Jampol NS (2010). Attributions of intentions and fairness judgments regarding interracial peer encounters. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1206–1213. 10.1037/a0019660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus MW, & Keltner D (2013). Social class rank, essentialism, & punitive judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 247–261. 10.1037/a0032895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlothlin H, & Killen M (2006). Intergroup attitudes of European American children attending ethnically homogeneous schools. Child Development, 77, 1375–1386. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00941.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlothlin H, & Killen M (2010). How social experience is related to children’s intergroup attitudes. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 625–634. 10.1002/ejsp.733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Brown CS, White ES, Chow KA, & Gillen-O’ Neel C (2015). Elementary school children’s reasoning about social class: A mixed-methods study. Child Development, 86, 1653–1671. 10.1111/cdev.12407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale D (2004). Social identity processes and children’s ethnic prejudice. In Bennett M & Sani F (Eds.), The Development of the Social Self (pp. 219–246). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Niehues J (2014). Subjective perceptions of inequality and redistributive preferences: An international comparison. http://www.relooney.com/NS3040/000_New_1519.pdf

- Quintana SM, & Vera EM (1999). Mexican American children’s ethnic identity, understanding of ethnic prejudice, and parental ethnic socialization. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 21, 387–404. 10.1177/0739986399214001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, & Umaña-Taylor A (2019). Below the surface: Talking with teens about race, ethnicity and identity. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruck MD, Mistry RS, & Flanagan CA (2019). Children’s and adolescents’ understanding and experiences of economic inequality: An introduction to the special section. Developmental Psychology, 55, 449–456. 10.1037/dev0000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutland A, & Killen M (2015). A developmental science approach to reducing prejudice and social exclusion: Intergroup processes, social-cognitive development, and moral reasoning. Social Issues and Policy Review, 9, 121–154. 10.1111/sipr.12012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KE, Shutts K, & Devine PG (2020). Parents’ role in addressing children’s racial bias: The case of speculation without evidence. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15, 1178–1186. 10.1177/1745691620927702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman CK (2012). Rich man, poor man: Developmental differences in attributions and perceptions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 113, 415–429. 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeeding T (2016). The case for reducing child poverty in America. Pathways: Stanford Center on Poverty & Inequality. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development: How teens construct their worlds. West Sussex, England: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner JC (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In Austin WG & Worchel S (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Tamang DD (2014). Introduction: Citizens, society, and state. Crafting an inclusive future for Nepal. In Tamang DD & Maharjan MR (Eds.), Citizens, society, and state. Crafting an inclusive future for Nepal (pp. 1–10). Mandala Book Point. [Google Scholar]