Abstract

Context

During the fall of 2020, some high schools across the United States allowed their students to participate in interscholastic sports while others cancelled or postponed their sport programs due to concerns regarding COVID-19 transmission. What effect this has had on the physical and mental health of adolescents is unknown.

Objective

To identify the effect of playing a sport during the COVID-19 pandemic on the health of student-athletes.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Sample recruited via email.

Patients or Other Participants

A total of 559 Wisconsin high school athletes (age = 15.7 ± 1.2 years, female = 43.6%, male = 56.4%) from 44 high schools completed an online survey in October 2020. A total of 171 (30.6%) athletes played (PLY) a fall sport, while 388 (69.4%) did not play (DNP).

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Demographic data included sex, grade, and sport(s) played. Assessments were the General Anxiety Disorder-7 Item for anxiety, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item for depression, the Hospital for Special Surgery Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale for physical activity, and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 for quality of life. Univariable comparisons between the 2 groups were made via t tests or χ2 tests. Means for each continuous outcome measure were compared between groups using analysis-of-variance models that controlled for age, sex, teaching method (virtual, hybrid, or in person), and the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

Results

The PLY group participants were less likely to report moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety (PLY = 6.6%, DNP = 44.1%, P < .001) and depression (PLY = 18.2%, DNP = 40.4%, P < .001). They also demonstrated higher (better) Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale scores (PLY = 23.2 [95% CI = 22.0, 24.5], DNP = 16.4 [95% CI = 15.0, 17.8], P < .001) and higher (better) Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory total scores (PLY = 88.4 [95% CI = 85.9, 90.9], DNP = 79.6 [95% CI = 76.8, 82.4], P < .001).

Conclusions

Adolescents who played a sport during the COVID-19 pandemic described fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression and had better physical activity and quality-of-life scores compared with adolescent athletes who did not play a sport.

Keywords: public health, youth, anxiety, depression

Key Points

High school students who played a sport during the COVID-19 pandemic in the fall of 2020 were less likely to report anxiety and depression symptoms than athletes who did not play a sport.

Compared with high school athletes who did not play a sport, those who did play a sport during the COVID-19 pandemic in the fall of 2020 demonstrated higher physical activity and quality-of-life scores.

Participation in high school sports may have significant physical and mental health benefits for US adolescent athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

An estimated 8.4 million US high school students participate in interscholastic athletics each year.1 Adolescent sport participation has been recognized as having profound positive influences on the health and wellbeing of adolescent students, as evidenced by higher academic achievement, greater levels of physical activity, and decreased levels of anxiety and depression compared with students who did not participate in athletics.2 Additionally, high school sport participation is one of the most important factors for life-long physical activity and health.3

During the spring of 2020, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the disease caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), reached pandemic levels in the United States. Schools were closed and high school sports were cancelled to slow the spread of the disease. Experts4,5 have suggested that although necessary to slow the community spread of the virus, the COVID-19 mitigation strategies may have had profound mental and physical health consequences for students and may have increased the likelihood that youth engaged in sedentary activities and the prevalence of childhood obesity.

Researchers6 have also shown that females, older athletes, team sport participants, and athletes from areas with higher levels of poverty reported more symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as lower levels of physical activity and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in May 2020 during the widespread shutdown. In another study,7 adolescent athletes in May 2020 described more mental health symptoms and displayed lower physical activity and HRQoL scores than similar samples of adolescent athletes before the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the fall of 2020, 14 states in the United States (27%) allowed full fall sport participation and 30 states (60%) allowed modified sport participation; the remaining 6 states and the District of Columbia (13%) did not allow any interscholastic athletic participation.8 In addition, within each state that allowed full or modified participation, individual school districts could determine which sports they offered. Some schools allowed all their fall sports, while other districts sponsored a portion of their sports and postponed or cancelled other sports.9

A drawback to the recent studies regarding the effect of COVID-19 on the health of adolescent athletes was the difficulty discerning if the health changes reported were primarily due to restrictions on sport participation or due to other factors, such as the lack of in-person school attendance, increased economic uncertainty, or concerns about contracting the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. Therefore, it is important to determine if sport participation independently affected the health of adolescent athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We are not aware of any research to date that has specifically documented how sport participation during the COVID-19 pandemic affected the mental and physical health of adolescent athletes. This information may assist sports medicine providers, school administrators, and health care policy experts in implementing strategies to improve the short-term and long-term mental and physical health of adolescent athletes in the months and years to come as we transition from the COVID-19 pandemic.10 Thus, the purpose of our study was to measure the effect of sport participation on the mental and physical health of adolescent athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. To accomplish this, we compared self-report data on anxiety, depression, physical activity, and HRQoL for a cohort of athletes who played a sport with a similar cohort of athletes who did not play a sport in Wisconsin during the fall of 2020. We hypothesized that adolescent student-athletes who played a sport would display better mental health, physical activity, and HRQoL than student-athletes who did not play a sport.

METHODS

This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Institutional Review Board in September 2020. During the summer of 2020, return-to-sport guidelines were provided by the National Federation of High School Associations to all high schools in the United States.8 These guidelines specifically mentioned best practices to reduce the spread of COVID-19 transmission and listed the potential risk of COVID-19 transmission by the type of sport.8 Wisconsin allowed individual school districts to determine whether to sponsor interscholastic teams during the fall of 2020.11 Approximately 305 (60%) of the 510 schools opted to sponsor teams for all fall sports, while 104 (20%) opted to offer a limited number of sports, and the remaining 101 (20%) offered no fall sports at their schools. The sports offered most often by schools were boys' and girls' cross-country (78%) and girls' golf (72%). The sports offered least often were football (54%), boys' soccer (50%), and girls' swimming (50%).12

Wisconsin high school athletes (males and females: grades = 9–12, age = 13–19 years) were recruited to participate in the study by completing an anonymous online survey in October 2020. Emails were sent to athletic trainers and coaches at 44 schools to solicit their athletes to participate in the study. The survey was completed anonymously, so no personal health information was collected from participants. However, the survey information pages required the potential participants to acknowledge having read the study information and received their parents' permission to complete the survey. If they clicked yes, they were directed automatically to the survey. If they clicked no, the survey ended. This is standard practice for most anonymous online surveys. The survey contained 69 items and included a section on demographic information, followed by 3 validated instruments used to measure physical activity, mental health, and HRQoL in adolescents. Demographic responses regarding the participant's age, grade, and school name, as well as any high school sport in which he or she competed during the fall and planned to compete in if the sport was offered by the school during the winter and spring of the 2020–2021 school year, were collected. The remainder of the survey consisted of assessments of mental health, physical activity level, and HRQoL.

Mental Health

The General Anxiety Disorder-7 Item (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item (PHQ-9) surveys were used to evaluate anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively.13 The questionnaires asked participants to rate the frequency of anxiety or depression symptoms experienced in the previous 2 weeks. The GAD-7 scale is a valid, reliable, and sensitive measure of anxiety symptoms and differentiated between mild and moderate GAD in adolescents.14 Scores range from 0 to 21, with a higher score indicating increased anxiety. In addition to the total score, GAD-7 categorical scores of 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, and 15–21 corresponded to no, mild, moderate, and severe anxiety symptoms, respectively.14 The PHQ-9 is a 9-item screening questionnaire for depression symptoms with scores ranging from 0 to 27; a higher score indicates a greater level of depression. The PHQ-9 has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for depression screening in adolescent patients aged 13 to 17 years.15 In addition to the total score, PHQ-9 categorical scores of 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–19, and >20 corresponded to minimal or none, mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression symptoms, respectively.16

Physical Activity

Physical activity level was assessed using the Hospital for Special Surgery Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale (HSS Pedi-FABS). This validated 8-item instrument was designed to measure the activity of children between 10 and 18 years old during the past month. Scores range from 0 to 30, with a higher score indicating greater physical activity.17,18

Health-Related Quality of Life

Health-related quality of life was measured with the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL). The 23-item PedsQL questionnaire assesses HRQoL during the previous 7 days. Physical summary (physical function) and psychosocial summary (a combination of emotional, social, and school function) scores, as well as the total PedsQL score, were calculated. Scores range from 0 to 100, and a higher score indicates greater HRQoL. The PedsQL has been validated for use in children ages 2 to 18 years.19,20

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed for the data of those who provided valid, complete surveys. Participants were excluded if they did not complete the entire survey, were not in grades 9 through 12, or indicated they did not plan to play interscholastic sports at their school. Demographic variables were summarized (mean ± SD or No. [%]) overall and by study respondents for sex and fall sport. Individuals were classified as playing (PLY) or not playing (DNP) a fall sport.

Investigated school characteristics were the type of instructional delivery method and the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. The type of instructional delivery method (online only, in person, or hybrid [a combination of in person and online]) was determined by reviewing the information on each school's website. The percentage of the students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch for each school was obtained from the publicly available online data through the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.21

We compared means and 95% CIs for each continuous outcome measure between fall sport participation groups by analysis-of-variance models that controlled for age, sex, type of teaching method, and percentage of students who were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. Ordinal logistic regression models were used to estimate the percentages of levels of anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9) by group. These models controlled for the same covariates listed earlier. All tests had a .05 significance level. Analyses were conducted in R for statistical computing (version 3.5; Foundation for Statistical Computing).

RESULTS

A total of 559 high school athletes (age = 15.7 ± 1.2 years, female = 43.6%, male = 56.4%) completed the survey. Due to the convenience sampling design, information regarding the response rate was unavailable. A total of 388 (69.4%) participants stated they did not play (DNP) an interscholastic sport at their school, whereas 171 (30.6%) reported they did play (PLY) an interscholastic sport. The majority (n = 257, 66.2%) of those in the DNP group attended schools that cancelled all fall sports, and 91.4% (n = 355) attended schools that delivered all instruction online. The percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch was 25.9% ± 10.3%. A summary of the participant characteristics is found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics for Adolescent Athletes Who Did or Did Not Play a High School Sport in the Fall 2020

| Variable |

All Participants (n = 559) |

Did Play a Fall Sport (n = 171) |

Did Not Play a Fall Sport (n = 388) |

P Value |

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 15.7 ± 1.2 | 15.7 ± 1.2 | 15.7 ± 1.2 | .895 |

| Sex, No. (%) | <.001 | |||

| Female | 244 (43.6) | 93 (54.7) | 151 (39.0) | |

| Male | 313 (56.4) | 77 (45.3) | 236 (61.0) | |

| Grade, No. (%) | .173 | |||

| 9 | 130 (23.3) | 40 (23.4) | 90 (23.2) | |

| 10 | 167 (29.9) | 51 (29.8) | 116 (29.9) | |

| 11 | 145 (25.9) | 36 (21.1) | 109 (28.1) | |

| 12 | 117 (20.9) | 44 (25.7) | 73 (18.8) | |

| No. of schools | 44 | 25 | 23 | |

| Instructional delivery method, No. (%) | <.001 | |||

| Online | 374 (66.9) | 19 (11.1) | 355 (91.4) | |

| Hybrid (in person and online) | 113 (20.2) | 83 (48.5) | 30 (7.7) | |

| In person | 72 (12.8) | 69 (40.3) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, No. (%) | 25.9 (10.3) | 34.0 (13.3) | 22.9 (7.0) | <.001 |

In the PLY group, 148 (86.5%) of the participants attended schools that offered all fall sports, with 40.3% (n = 69) attending school in person. Individuals in the PLY group were most likely to report playing volleyball (n = 66, 38.6%), football (n = 53, 31%), or boys' soccer (n = 22, 12.9%). Those in the DNP group most commonly noted that they had intended to play football (n = 160, 41.2%) or volleyball (n = 51, 13.1%); 79 (20.4%) did not play a fall sport but intended to play a high school winter or spring sport. A summary of planned sport participation is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Planned Sport Participation for Adolescent Athletes Who Did or Did Not Play a High School Sport in the Fall 2020, No. (%)

| Variable |

All Participants (n = 559) |

Did Play a Fall Sport (n = 171) |

Did Not Play a Fall Sport (n = 388) |

| Planned fall sport participation | |||

| Cheer or dance | 23 (4.1) | 3 (1.8) | 20 (5.2) |

| Cross-country | 41 (7.3) | 16 (9.4) | 25 (6.4) |

| Football | 213 (38.1) | 53 (31.0) | 160 (41.2) |

| Soccer (boys) | 53 (9.5) | 22 (12.9) | 31 (8.0) |

| Swim (girls) | 20 (3.6) | 1 (0.6) | 19 (4.9) |

| Tennis (girls) | 13 (2.3) | 10 (5.8) | 3 (0.8) |

| Volleyball | 117 (20.9) | 66 (38.6) | 51 (13.1) |

| None | 79 (14.1) | 79 (20.4) | |

| Planned winter or spring participation | |||

| Baseball | 103 (18.4) | 31 (18.1) | 72 (18.6) |

| Ice hockey | 22 (3.9) | 4 (2.3) | 18 (4.6) |

| Lacrosse | 32 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (8.2) |

| Soccer (girls) | 205 (36.7) | 82 (48.0) | 123 (31.7) |

| Softball | 66 (11.8) | 33 (19.3) | 33 (8.5) |

| Swim (boys) | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.8) |

| Tennis (boys) | 7 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.8) |

| Track | 120 (21.5) | 48 (28.1) | 72 (18.6) |

| Wrestling | 35 (6.3) | 8 (4.7) | 27 (7.0) |

| Other sporta | 24 (4.3) | 3 (1.8) | 21 (5.4) |

Other sport includes bowling, gymnastics, rugby, power lifting, and skiing (alpine and downhill).

Mental Health

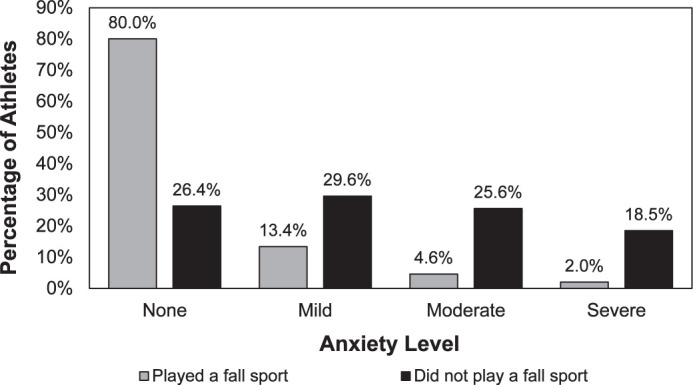

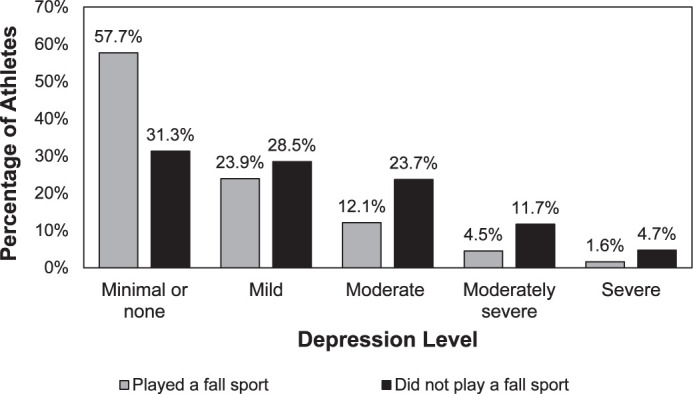

The PLY participants were more likely to demonstrate GAD-7 symptom scores of 0 to 4, indicating no or minimal anxiety (PLY = 80.0% versus DNP = 26.4%), whereas the DNP athletes were more likely to display scores of 10 to 21, indicating more moderate to severe anxiety than the PLY group (DNP = 44.1% versus PLY = 6.6%; Figure 1). The PLY group was more likely to provide PHQ-9 scores of 0 to 4, reflecting no or minimal depression (PLY = 57.7% versus DNP = 31.3%), whereas the DNP athletes were more likely to report scores of 10 to 27, indicating more moderate to severe depression than the PLY group (DNP = 40.1% versus PLY = 18.2%; Figure 2). The DNP group had a higher (ie, worse) GAD-7 score than the PLY group (8.4 [95% CI = 7.2, 9.5] versus 3.2 [95% CI = 2.2, 4.3], P < .001) as well as a higher (ie, worse) PHQ-9 score than the PLY group (7.6 [95% CI = 6.4, 8.8] versus 3.9 [95% CI = 2.8, 4.9], P < .001). The total GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores for both groups are found in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of anxiety symptoms for adolescent athletes who did and those who did not play a high school sport in the fall of 2020.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of depression symptoms for adolescent athletes who did and those who did not play a high school sport in the fall of 2020.

Table 3.

Comparison of Anxiety, Depression, Physical Activity, and Quality-of-Life Scores for Adolescent Athletes Who Did and Those Who Did Not Play a High School Sport in the Fall of 2020

| Variable |

All Participants (n = 559) |

Did Play a Fall Sport (n = 171) |

Did Not Play a Fall Sport (n = 388) |

P Value |

| General Anxiety Disorder-7 Item total score | 6.5 (5.8, 7.2)a | 3.2 (2.2, 4.3) | 8.4 (7.2, 9.5) | <.001 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item total score | 6.3 (5.6, 7.1) | 3.9 (2.8, 4.9) | 7.6 (6.4, 8.8) | <.001 |

| Hospital for Special Surgery Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale total score | 18.7 (17.9, 19.6) | 23.2 (22.0, 24.5) | 16.4 (15.0, 17.8) | <.001 |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 score | ||||

| Physical summary score | 88.4 (86.9, 89.9) | 92.3 (90.1, 94.4) | 86.5 (84.1, 88.9) | .004 |

| Psychosocial summary score | 79.5 (77.5, 81.6) | 86.4 (83.3, 89.4) | 75.9 (72.5, 79.3) | <.001 |

| Total score | 82.6 (80.9, 84.3) | 88.4 (85.9, 90.9) | 79.6 (76.8, 82.4) | <.001 |

Values in parentheses represent the 95% CI when age, sex, teaching delivery (in person, online, or hybrid) method, and percentage eligible for free or reduced-price lunch were controlled.

Physical Activity and HRQoL

Physical activity, as measured by HSS Pedi-FABS scores for the PLY group, was 41% higher (ie, better) than for the DNP group (PLY = 23.2 [95% CI = 22.0, 24.5] versus DNP = 16.4 [95% CI = 15.0, 17.8], P < .001; Table 2). The HRQoL for athletes in the PLY group was higher (better) than for the DNP athletes. Specifically, the PedsQL physical health summary score for the PLY group were higher than for the DNP group (PLY = 92.3 [95% CI = 90.1, 94.4] versus DNP = 86.5 [95% CI = 84.1, 88.9], P = .004), as was the psychosocial health summary score (PLY = 86.4 [95% CI = 83.3, 89.4] versus DNP = 75.9 [95% CI = 72.5, 79.3], P < .001) and the total PedsQL score (PLY = 88.4 [95% CI = 85.9, 90.9] versus DNP = 79.6 [95% CI = 76.8, 82.4], P < .001; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the mental health status, physical activity level, and HRQoL between high school athletes who were and those who were not able to participate in interscholastic sports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our work builds on research6,7 that demonstrated dramatic changes in physical and mental health after the cancellation of high school sports in the spring of 2020. A limitation of the prior investigations was difficulty discerning if the health changes reported were primarily due to the restrictions on sport participation or the result of other factors such as sex, age, socioeconomic status, or the lack of in-person school attendance. After controlling for grade, sex, school instructional delivery method, and the percentage of students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch, we found that athletes who did not play interscholastic sports in the fall 2020 experienced worse symptoms of anxiety and depression, lower levels of physical activity, and worse HRQoL than athletes who did play sports during that time. This suggests that the reinitiation of sport participation may result in significant improvements in mental and physical health for adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mental Health

Athletes who played high school sports in the fall of 2020 demonstrated fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression than those athletes who did not play a sport. Specifically, the DNP group was more than 6 times as likely to describe moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and more than twice as likely to acknowledge moderate to severe symptoms of depression, even after we adjusted for age, sex, type of school instruction, and percentage of students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch. This seemed to suggest that although PLY athletes continued to experience slightly higher levels of depression and anxiety than historical values, the mental health burden among DNP athletes was considerably worse.7 In fact, the DNP group displayed levels of moderate to severe anxiety and depression symptoms similar to those identified in a nationwide sample of adolescent athletes in May 2020 (anxiety = 36.7%, depression = 27.1%).7 Given the adolescent mental health crisis that existed before the onset of COVID-19 and the known mental health benefits of sport participation, these data seemed to indicate that adolescent athletes who are unable to return to sports may be at a significantly greater risk for mental health concerns.

Experts22 have pointed out that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the mental health of youth, which may be related to decreased socialization, increased family strain, and reduced access to support services. As such, we recognized that factors beyond sport participation, such as the ability to attend school in person, may have contributed to adolescent mental health. In addition, anxiety and depression in adolescent athletes have been associated with sex and grade in school. Nonetheless, after controlling for the type of school instructional delivery (online, in person, or hybrid), age, and sex, sport participation remained significantly associated with large improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms. Therefore, we can reasonably assume that the increased symptoms we identified among the DNP group were at least partly attributable to the lack of sport participation.

Our results also support previous findings23,24 that sport participation improved the mental health of youth and adolescents. Recent authors7 observed that during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, 11.4% of student athletes who were unable to participate in sports reported moderate to severe levels of depression symptoms, which was 4 times higher than the rate (2.8%) seen in student-athletes before the COVID-19 pandemic. This outcome supports the premise that sport participation may represent an important mechanism for improving the mental health of adolescents as society continues to attempt to mitigate the effect of COVID-19 in the months and years to come.

Physical Activity

During the COVID-19 pandemic, high school athletes who played high school sports had a higher level of physical activity than athletes who did not play a sport. Notably, the total HSS Pedi-FABS score for the PLY group was similar to scores for healthy high school–aged athletes before COVID-19 (24.7 [95% CI = 24.5, 24.9]).7 Similarly, the HSS Pedi-FABS scores for the PLY group were similar to scores for adolescents from Donovan et al (23.8 ± 5.3)25 as well as to normative data from Fabricant et al (20.2 ± 7.2).18 Further, the HSS Pedi-FABS scores for the PLY group were nearly twice as high as those in high school athletes who were unable to play any sports in May 2020 (12.1 [95% CI = 11.7, 12.5]). Finally, the DNP group's scores were 25% and 45% lower than scores reported by Fabricant et al18 and Donovan et al,25 respectively. This may indicate that playing a sport enabled these athletes to mitigate, to some degree, the low level of physical activity during the initial onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Physical activity is known to have a beneficial effect on a wide range of health outcomes in adolescents, including sleep, academic success, wellbeing, and mental health.3,4,26 Therefore, the identified decrease in mental health in the DNP group may have been at least partly due to the removal of the positive effects of physical activity in adolescents. In addition, childhood obesity was a public health crisis before COVID-19 and is projected to become worse as a result.5 Decreased physical activity in adolescents may also have long-term negative effects and implications in terms of increased risks for obesity and cardiometabolic disease if these levels remain low for prolonged periods.27 Chronically low levels of physical activity may also compound the mental health consequences of the current crisis and increase the risk.28 Returning to high school sport opportunities is a complex situation and requires careful consideration. Stakeholders should consider the promotion of physical activity for adolescents a top priority during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Health-related quality of life is a measure of wellbeing, which has been associated with self-perceived health, longevity, and healthy behaviors.29 We found that adolescent athletes who had returned to sport in fall 2020 demonstrated higher HRQoL than those athletes who were unable to return to sport. This finding is consistent with prior studies30–33 that showed individuals with increased physical activity or interscholastic sport participation (or both) had higher HRQoL scores than inactive adolescents and high school nonathletes. Therefore, it is not surprising that HRQoL scores for the PLY athletes were higher than those for the DNP athletes.

The total PedsQL score for the PLY athletes was higher than the score for high school athletes when sports were cancelled (mean = 76.7, 95% CI = 76.0, 77.5).6 Further, the total PedsQL score reported by the PLY athletes was similar to scores recorded in 14- to 18-year-old athletes before the pandemic by Lam et al (89.4 ± 9.6 to 90.5 ± 10.2),31 Snyder et al (89.5 ± 10.1 to 93.6 ± 7.6),30 and McGuine et al7 (90.9 ± 0.4). The increased score for the PLY group may also be attributed to aspects of sport participation beyond the opportunity for structured physical activity, such as goal setting, emotional support, and social interaction with teammates. Thus, by playing a sport, adolescents may be able to return to a “normal” or “expected” level of HRQoL, similar to that experienced before the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the other hand, the total PedsQL score (mean ± SD) for the DNP athletes was lower (79.6 ± 2.8) than in nonathletes (85.8 ± 11.4) reported by Lam et al.31 Interestingly, the DNP score was similar to scores reported in populations of youth ages 5 to 18 years with chronic conditions such as asthma (74.8 ± 16.5), cardiac disease (77.4 ± 14.5), and diabetes (80.3 ± 12.9) as determined by Varni et al.32 The reduced HRQoL in the DNP group may have been due in part to the decreased physical activity levels we noted previously. However, because HRQoL is multifactorial, the score for the DNP group was likely also affected by other consequences of the lack of sport participation, such as the continued loss of social interaction and loss of identity. Nonetheless, this difference persisted after we controlled for school instructional delivery type, grade, sex, and the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, suggesting that the differences may reflect the lack of sport participation itself. Further, the fact that the PLY group's HRQoL was similar to data collected before the pandemic may indicate that providing sport opportunities can positively influence multiple dimensions of adolescent health. Moving forward, validated health and wellbeing measurements provide a common metric for future researchers to compare their results with our data.33 These metrics may help policymakers with decisions that affect the health and wellbeing of student-athletes in the coming months and years as we transition beyond the immediate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.34

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the data were self-reported to online surveys and were not the result of a clinical examination conducted by a health care provider. Still, our findings were consistent with those from investigators4 and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,34 who stated that COVID-19 would influence the mental and physical health of youth. Second, we acknowledge that a response bias may have been present. We cannot know for certain if the sample was representative of all the athletes at the schools or biased toward athletes who were more likely to respond if they experienced the most profound effects on their health. Third, due to the survey delivery method, our sample may have been biased toward athletes from higher socioeconomic groups with easy access to internet services. Fourth, we used the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch for each school as a measure of economic status for individual respondents. We believed this would be more accurate as a measure of economic status than asking students to accurately report their household income. Finally, we recognize that mental health and overall wellbeing are complex and potentially affected by other factors for which we were not able to account and which could have confounded the results. Specifically, we did not ask the respondents whether they had any fear of contracting the COVID-19 virus. However, we were able to control for sex, age, school instruction, and the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch to better define the effects that sport participation may have during COVID-19. Future authors could improve our understanding of the effect of sport on adolescent health by including nonathletes to compare with athletes who could and those who could not participate in sport.

CONCLUSIONS

Adolescent athletes who were able to return to sport participation in fall 2020 reported dramatically lower symptoms of anxiety and depression, higher physical activity levels, and higher HRQoL, even after we adjusted for grade, sex, and the type of school instructional delivery. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, we hope that this information will help inform public health experts, school administrators, and sports medicine and mental health providers regarding the potential physical and mental health benefits associated with participation in organized sports for adolescents. We recognize that returning to organized sports is a complex topic and requires careful consideration. Nonetheless, research continues to suggest that sport participation during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with significant mental and physical health benefits in adolescents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge and thank all the student-athletes who participated in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Participation in school athletics. Child Trends. 2020. Accessed July 12. https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/participation-in-school-athletics .

- 2.Bailey R. Physical education and sport in schools: a review of benefits and outcomes. J Sch Health . 2006;76(8):397–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kniffin KM, Wansink B, Shimizu M. Sports at work: anticipated and persistent correlates of participation in high school athletics. J Leadersh Organ Stud . 2015;22(2):217–230. doi: 10.1177/1548051814538099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr . 2020;174(9):819–820. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An R. Projecting the impact of the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic on childhood obesity in the United States: a microsimulation model. J Sport Health Sci . 2020;9(4):302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGuine TA, Biese KM, Petrovska L, et al. The health of US adolescent athletes during Covid-19 related school closures and sport cancellations. J Athl Train . 2020]. [published online ahead of print November 5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.McGuine TA, Biese K, Hetzel SJ, et al. Changes in the health of adolescent athletes: a comparison of health measures collected before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Athl Train . 2021;56(8):836–844. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0739.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidance for opening up high school athletics and activities. National Federation of State High School Associations. 2020. Accessed December 28. https://www.nfhs.org/media/3812287/2020-nfhs-guidance-for-opening-up-high-school-athletics-and-activities-nfhs-smac-may-15_2020-final.pdf .

- 9.Sports seasons modifications update. National Federation of State High School Associations. 2020. Accessed December 9. https://www.nfhs.org/articles/sports-seasons-modifications-update/

- 10.Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health . 2020;14:20. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Board defines alternate fall season; winter & spring seasons shortened. Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association. 2020. Accessed November 14. https://www.wiaawi.org/News/bulletin-issue-1-2020-21 .

- 12.Schools declare for fall or alternate fall season sport season. Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association. 2020. Accessed November 14. https://www.wiaawi.org/Sports/Fall/Girls-Volleyball/News/schools-declare-for-fall-or-alternate-fall-season .

- 13.Andrews JH, Cho E, Tugendrajch SK, Marriott BR, Hawley KM. Evidence-based assessment tools for common mental health problems: a practical guide for school settings. Child Sch . 2020;42(1):41–52. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdz024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mossman SA, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK, et al. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: signal detection and validation. Ann Clin Psychiatry . 2017;29(4):227A–234A. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, et al. Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics . 2010;126(6):1117–1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke K, Wu J, Yu Z, et al. Patient Health Questionnaire Anxiety and Depression Scale: initial validation in three clinical trials. Psychosom Med . 2016;78(6):716–727. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabricant PD, Robles A, Downey-Zayas T, et al. Development and validation of a pediatric sports activity rating scale: the Hospital for Special Surgery Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale. Pedi-FABS HSS, editor. Am J Sports Med . 2013;41(10):2421–2429. doi: 10.1177/0363546513496548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabricant PD, Suryavanshi JR, Calcei JG, Marx RG, Widmann RF, Green DW. The Hospital for Special Surgery Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale (HSS Pedi-FABS): normative data. Am J Sports Med . 2018;46(5):1228–1234. doi: 10.1177/0363546518756349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care . 2001;39(8):800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr . 2003;3(6):329–341. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0329:tpaapp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.School nutrition program statistics. Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. 2020. Accessed January 1. https://dpi.wi.gov/school-nutrition/program-statistics .

- 22.Singh S, Roy D, Sinha K, Parveen S, Sharma J, Joshi G. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: a narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res . 2020;293:113429. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vella SA, Cliff DP, Magee CA, Okely AD. Associations between sports participation and psychological difficulties during childhood: a two-year follow up. J Sci Med Sport . 2015;18(3):304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vella SA. Mental health and organized youth sport. Kinesiol Rev . 2019;8(3):229–236. doi: 10.1123/kr.2019-0025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donovan L, Hetzel S, Laufenberg CR, McGuine TA. Prevalence and impact of chronic ankle instability in adolescent athletes. Orthop J Sports Med . 2020;8(2):2325967119900962. doi: 10.1177/2325967119900962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valkenborghs SR, Noetel M, Hillman CH, et al. The impact of physical activity on brain structure and function in youth: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20184032. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J, Välimäki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a 21-year tracking study. Am J Prev Med . 2005;28(3):267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, Perrin EM, Armstrong SC. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in US children, 1999–2016. Pediatrics . 2018;141(3):e20173459. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Accessed December 3. https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/wellbeing.htm .

- 30.Snyder AR, Martinez JC, Bay RC, Parsons JT, Sauers EL, Valovich McLeod TC. Health-related quality of life differs between adolescent athletes and adolescent nonathletes. J Sport Rehabil . 2010;19(3):237–248. doi: 10.1123/jsr.19.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lam KC, Valier AR, Bay RC, McLeod TC. A unique patient population? Health-related quality of life in adolescent athletes versus general, healthy adolescent individuals. J Athl Train . 2013;48(2):233–241. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.2.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM. Impaired health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic conditions: a comparative analysis of 10 disease clusters and 33 disease categories/severities utilizing the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes . 2007;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson A, Koontz JS. Youth sports in the wake of COVID-19: a call for change. Br J Sports Med . 2021;55(14):764. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-103288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2020;69(32):1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]