Abstract

The primary startle response (SR) is an innate reaction evoked by sudden and intense acoustic, tactile or visual stimuli. In rodents and humans the SR involves reflexive contractions of the face, neck and limb muscles. The acoustic startle response (ASR) pathway consists of auditory nerve fibers (AN), cochlear root neurons (CRNs) and giant neurons of the caudal pontine reticular nucleus (PnC), which synapse on cranial and spinal motor neurons. The tactile startle response (TSR) is transmitted by primary sensory neurons to the principal sensory (Pr5) and spinal (Sp5) trigeminal nuclei. The ventral part of Pr5 projects directly to the PnC neurons. The SR requires rapid transmission of sensory information to initiate a fast motor response. Alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPAR) are necessary to transmit auditory information to the PnC neurons and elicit the SR. AMPARs containing the glutamate AMPAR subunit 4 (GluA4) have fast kinetics, which makes them ideal candidates to transmit the SR signal. This study examined the role of GluA4 within the primary SR pathway by using GluA4 knockout (GluA4-KO) mice. Deletion of GluA4 considerably decreased the amplitude and probability of successful ASR and TSR, indicating that the presence of this subunit is critical at a common station within the startle pathway. We conclude that deletion of GluA4 affects the transmission of sensory signals from acoustic and tactile pathways to the motor component of the startle reflex. Therefore, GluA4 is required for the full response and for reliable elicitation of the startle response.

Keywords: Startle reflex, AMPAR, GluA4, Caudal pontine reticular nucleus (PnC), principal sensory trigeminal nucleus (Pr5)

Introduction

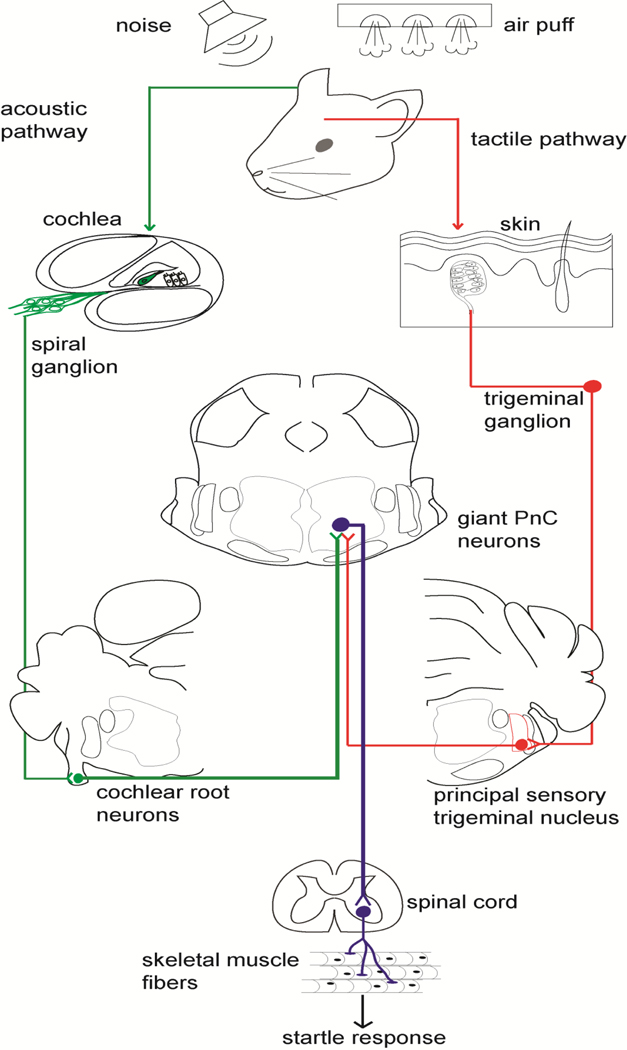

The primary startle response (SR; Fig. 1) is an innate reaction rapidly evoked by a sudden and intense sensory stimulus (Davis et al., 1982; Koch, 1999). In rodents and humans, the SR is expressed behaviorally as reflexive contractions of the face, neck and limb muscles (Caeser et al., 1989; Lingenhöhl and Friauf, 1994). The SR can be elicited by acoustic (Berg and Balaban, 1999; Koch, 1999; Yeomans et al., 2002), tactile (Berg and Balaban, 1999; Schmid et al., 2003; Yeomans et al., 2002) or visual (Berg and Balaban, 1999; Blumenthal et al.2005; Yates and Brown, 1981) stimuli. The acoustic startle response (ASR) is the most extensively studied and its neuronal substrates have been described; it is initiated peripherally through the auditory pathway and centrally processed by only three synapses (Lingenhöhl and Friauf, 1994). The first synapse is made by auditory nerve fibers (AN) on the cell bodies of the cochlear root neurons (CRNs; Harrison et al., 1962; Merchan et al., 1988). The second synapse is made by the thick axons of the CRNs on the giant neurons of the caudal pontine reticular nucleus, the so-called PnC neurons (Kandler and Herbert, 1991; Lingenhöhl and Friauf, 1994; Lopez et al., 1999). The PnC neurons make the third synapse on cranial and spinal motor neurons to elicit the startle response (Lingenhöhl and Friauf, 1994).

Figure 1. Diagram representing current knowledge of the acoustic and tactile startle pathways relevant to this study.

High intensity (broadband or octave centered) acoustic stimulation delivered suddenly activates hair cells in the cochlea, which send acoustic information through the spiral ganglion neurons that form the auditory nerve (AN). The AN sends signals to large neurons in the cochlear root (CRN). The CRNs project mainly contralaterally to giant neurons in the caudal pontine reticular formation (PnC), which mediate the acoustic startle response.

Air puffs applied to the dorsum of the head effectively stimulate skin receptors that send tactile information through the trigeminal nerve, mainly the ophthalmic branch. The trigeminal nerve transmits the signal mainly to neurons in the principal sensory nucleus (Pr5). The caudal Pr5 projects directly to the PnC, which mediates the tactile startle response. Acoustic and tactile startle modalities converge on giant PnC neurons, which project directly to motoneurons and motor interneurons in the spinal cord. These spinal motoneurons in turn activate skeletal muscles to elicit a fast motor response.

The tactile startle response (TSR) pathway (Fig. 1) is less clear. It has been proposed that sensory information from skin receptors in the head is transmitted by primary sensory neurons to the principal sensory (Pr5) and spinal (Sp5) trigeminal nuclei (Yeomans et al., 2002). The ventral portion of Pr5 projects directly to the PnC neurons (Schmid et al., 2003; Yeomans et al., 2002), where the acoustic and tactile pathways converge (Yeomans et al., 2002).

The SR requires rapid transmission of sensory information to initiate a fast motor response. Ionotropic glutamate receptors are necessary to transmit auditory information to the PnC neurons and evoke startle (Ebert and Koch, 1992; Krase et al., 1993; Miserendino and Davis, 1993; Steidl et al., 2004), particularly those of the AMPAR subtype (AMPARs) (Davis et al., 1999; Krase et al., 1993; Ebert and Koch, 1992). Among the AMPARs with the fastest kinetics are those that contain the GluA3 and GluA4 subunits (Geiger et al., 1995; Mosbacher et al., 1994), and such kinetics makes them ideal candidates to rapidly transmit the SR signal. In the auditory pathway, these AMPAR subunits are commonly found in the cochlear nucleus and in the superior olivary complex (Gardner et al., 1999; Hunter et al., 1993; Rubio and Wenthold, 1997; Schmid, et al., 2001). In the ASR pathway, GluA4 is present in the cochlear nerve root (Gomez-Nieto et al., 2008), and a decreased ASR was previously noted in GluA4-KO mice (Sagata et al., 2010). In the TSR pathway, GluA4 is expressed in the trigeminal ganglion (Fernández-Montoya et al., 2016). However, the presence of GluA4 along the SR pathway and its functional role in the tactile and the acoustic startle has not been examined.

There are numerous studies employing extrinsic modulation of the SR (e.g. habituation, sensitization, fear-potentiation and pre-pulse inhibition) to assess sensory processing in rodents and humans (Koch and Schnitzler, 1997; Sinclair et al., 2016), with a strong focus on modulation by cognitive processes (Fendt and Koch, 2013; Hoffman, 1999; Sagata et al., 2010; Sinclair et al., 2017). Only a few studies, however, have focused on the elementary SR itself (Poli and Angrilli, 2015). Importantly, a requirement to understand the extrinsic modulation of the SR is a reliable primary startle response and knowledge of its intrinsic properties (Ison, 2001; Koch and Schnitzler, 1997), as the modulation of SR is affected by the primary startle reactivity (Csomor et al., 2008; Hoffman and Searle, 1968). The present study aims to advance the understanding of the mechanisms underlying fast glutamatergic transmission in the primary SR, particularly to determine the functional role of GluA4 within the primary SR pathway by using GluA4-KO mice.

Our results indicate that GluA4-containing AMPARs are necessary to fully elicit the acoustic and tactile SR. This provides a new perspective on the importance of AMPAR subunit composition in the primary SR pathway.

Methods

Animals

A total of sixty-six mice (33 wild type and 33 GluA4-KO) were used for this study. The number of mice used for each experiment is stated in the corresponding figure legend. All the experiments were performed using male mice that were eight to twelve weeks of age. All experimental procedures were in accordance with the National Institute of Health guidelines and approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

The generation of GluA4-KO mice (B6.129-Gria4tm1Rlh/J) has been described (Gardner et al, 2005). The mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and housed in an on-site colony at the Division of Laboratory Animal Resources facility at the University of Pittsburgh. Heterozygous mice were intercrossed to generate homozygous (KO), heterozygous and wild type (WT) offspring. Genotypes were confirmed by PCR. The experimenter was blind to the genotype.

Auditory brainstem response (ABR)

Auditory Brainstem Responses (ABRs) are commonly used to assess auditory function in humans and laboratory animals. ABRs are short-latency auditory-evoked far field potentials. In mice, these field potentials are typically recorded using sub dermal electrodes (see below). The field potentials represent the summed neural responses from specific regions of the auditory pathway (from the auditory nerve to the inferior colliculus) (Henry, 1979; Jewett et al., 1970; Melcher and Kiang, 1996). All recordings were conducted in a soundproof chamber and using a Tucker-Davis Technologies (Alachua, FL) recording system as previously described (García-Hernández et al., 2017). Click or tone stimuli were presented to isoflurane-anesthetized mice through a calibrated multi-field magnetic speaker connected to a 2-mm diameter plastic tube inserted into the ear canal. ABRs were recorded by placing subdermal needle electrodes at the vertex of the scalp, at the ventral border of the right pinna and at the ventral border of the left pinna. ABRs were recorded in response to broadband noise clicks (0.1 ms) or tone pips of 4, 8, 12, 16, 24 and 32 kHz (5 ms). Stimuli were presented with alternating polarity at a rate of 21 Hz, with an inter-stimulus interval of 47.6 ms. The intensity levels used were from 80 dB to 10 dB, in decreasing steps of 5 dB. The waveforms of 512 presentations were averaged, amplified 20x and digitalized through a low impedance preamplifier. The digitalized signals were transferred via optical port to a RZ6 processor, where the signals were band-pass filtered (0.3 – 3 kHz) and converted to analog form. The analog signals were digitized at a sample rate of ~200 kHz and stored for offline analyses. Hearing threshold levels were determined from the averaged waveforms, by identifying the lowest intensity level at which clear reproducible peaks were visible. Amplitudes of peak 1 and peak 2 (P1 and P2, respectively) were compared between WT and GluA4-KO mice. For measurements of amplitudes, the peaks and troughs from the click-evoked ABR waveforms were selected manually in BioSigRZ software and exported as CSV files. The peak amplitude was calculated as the height from the maximum positive peak to the following negative trough.

Acoustic and tactile startle responses

All behavioral experiments were conducted in the Rodent Behavior Analysis Core of the University of Pittsburgh between 9 a.m. and 1 p.m. Startle tests were conducted in a Hamilton-Kinder startle reflex station (SM100 version 7.00, 2006; Poway, CA). The station includes a build-in speaker in the ceiling of a sound-attenuated cabinet, a piezoelectric plate and a mouse restrainer, as well as a solenoid/regulator assembly to supply the air for the tactile startle reflex. The sensor plates of all the stations were calibrated with a 1 Newton (±0.05) force generator prior to each session. Responses are reported in Newtons. Sound level measurements inside the cabinet were made with a RadioShack sound level meter, model SMS PL-A (A scale). Stimuli were generated and recorded with the Hamilton-Kinder Startle Monitor software (7.00, 2006). Acoustic startle stimuli were delivered through the built-in speaker, and consisted of white noise bursts of 40 ms at different intensities according to the experimental sessions (see Experimental design). Tactile stimuli were air puffs of 40 ms duration. The air puffs were delivered through a 3/8” OD PVC tube with air holes that was part of the Hamilton-Kinder startle reflex station. The PVC tube was pressurized with air at 90 kPa. This delivery tube was attached to the mouse restrainer lid. The air holes pointed downward, so the air puffs were delivered to the dorsum of the head and thorax of the mouse, as those locations have been shown to be the most effective to evoke tactile startle (Yeomans et al., 2002). The solenoid/regulator assembly was covered with acoustical foam to reduce the acoustic noise generated by the solenoid. To avoid aversive stimulus and damage to the hair cells of the cochlea, we did not use loud sound to mask the noise of the air puff. Since the air puff noise itself produced a small acoustic startle, we elicited and measured this response in the absence of the tactile-elicited startle. To do so, we rotated the PVC tube 180 degrees upwards, towards the ceiling and away from the mouse, before presenting air puffs. This did elicit a small acoustic startle. This acoustic-elicited startle amplitude was measured and was later subtracted from the tactile elicited startle amplitude. Then, we rotated the PVC tube 180 degrees downwards so that subsequent air puffs were presented to the dorsal parts of the head and thorax of the mouse to elicit the tactile startle response.

Experimental design

To reduce anxiety, mice were acclimated to the experimental environment during three days previous to the actual startle response experiment. Littermates that consisted of one WT mouse and one GluA4-KO mouse (and occasionally two of each genotype, if the litter size was large enough) were tested in the same experimental session. Every experimental session started with 5 minutes of acclimation to a 65 dB background white noise before the test. The background noise remained throughout the entire session.

To evaluate the amplitude of the startle, each sound pressure level (65, 75, 85, 95, 105 or 115 dB) was presented ten times in a pseudo-randomized order; the inter-trial interval (ITI) varied randomly from 20 to 30 seconds (short ITI). To rule out muscle fatigue (Valsamis and Schmid, 2011), we also tested intervals of 40 to 60 sec (long ITI).

To assess short-term habituation (STH), we presented 50 consecutive trials of either the 105 dB white noise burst or the air puff (40 ms each), with a fixed ITI of 20 seconds to mice that were not previously exposed to any startle stimuli.

Data analysis

For each trial, the waveform of the startle response was recorded from 50 ms before to 100 ms after the onset of the startle-stimulus (Fig. 2a). Within each test, for a given mouse, the amplitude of the waveforms 50 ms before the stimulus onset, which represented spontaneous non-startle movements, was used as the baseline (Figs. 2c and 2d). Therefore, a discriminator criterion was defined as an amplitude level that was two standard deviations above the mean amplitude of these spontaneous movements, measured during 50 ms before the stimulus onset. The startle amplitude was defined as the maximum value of the first peak after the onset stimulus that exceeded the discriminator criterion (arrowheads in 2c and 2d). This first peak is situated within 50 ms following the stimulus onset. This first peak was considered to be a successful response and the amplitude and latency were measured and averaged. The percentage of responses that exceeded the two standard deviations (2SD) threshold was calculated. For every trial type, for a given mouse, the mean amplitude of the first peak was computed. The scripts for the waveform measurements were developed in MATLAB (R2016b, MathWorks, Natick, MA).

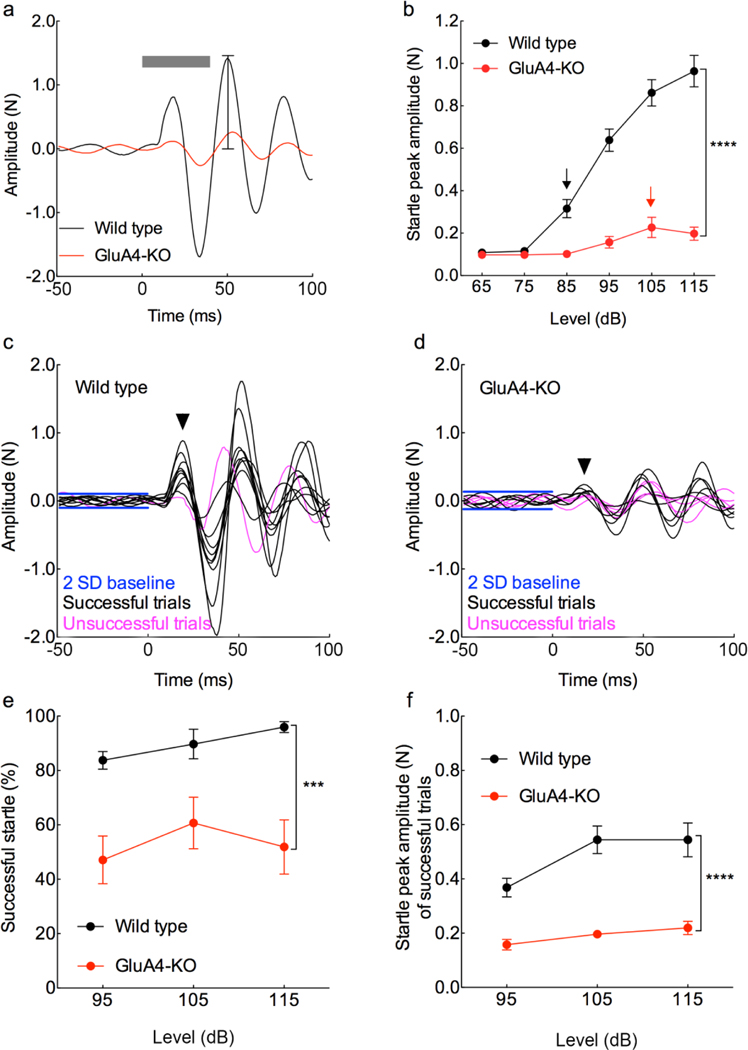

Figure 2. Deletion of GluA4 reduces the acoustic startle response (ASR).

a, Representative ASR waveform from a WT (black) and a GluA4-KO (red) mouse, elicited with 115 dB of white noise for 40ms (horizontal gray bar); the vertical bar in the second peak indicates the maximum peak amplitude detected automatically by the system (plotted in b). b, Mean maximum 2nd peak amplitude (±SEM) of the ASR as a function of sound level (dB) is significantly decreased in KO as compared to WT mice (F(1,15)=102.6, p< 0.0001; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 7 WT, 10 KO; Cohen’s f=2.4). There was also a significant effect of sound level (F(2.2,32.8)=105.8, p< 0.0001; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 7 WT, 10 KO; Cohen’s f=2.7). The threshold for the ASR is higher in the GluA4KO than in the WT mice (arrows) as shown by the genotype x sound level interaction (F(5,75)= 59.4, p< 0.0001; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 7 WT, 10 KO; Cohen’s f=2.0). c-d, Example of waveform traces of the ASR from WT and GluA4-KO mice used to determine the amplitude of the 1st peak (arrowheads) and the percentage of successful trials. e, Mean percentage of successful trials of the ASR is significantly reduced in the KO as compared to WT mice (F(1,16) = 19.8, p= 0.0004; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 8 WT, 10 KO; Cohen’s f=1.2). There was no effect of sound level (F(1.97,31.6)=1.34; p=0.28) and no interaction between genotype x sound level (F(2,32)=0.67, p=0.52). f, Mean amplitude of the 1st peak in successful trials of the ASR is significantly reduced in the KO as compared to WT mice (F(1,16) = 54.5, p< 0.0001; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 8 WT, 10 KO; Cohen’s f=3.0). There was an effect of sound level (F(1.78,28.4)=18.4, p< 0.0001; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 8 WT, 10 KO; Cohen’s f=1.1), and a low genotype x sound level interaction (F(2,32)=4.9, p=0.01; Cohen’s f=0.5).

Grip strength

To assess gross motor activity (muscular strength), a grip strength dynamometer (Chatillon, FDE050, Columbus Instruments, Ohio, USA) was used to test forepaw grip strength in WT and GluA4-KO mice. Each mouse was held by the tail and allowed to grasp the pull bar, then pulled backward horizontally. The peak force prior to release of the bar was displayed (in Newtons, N) on the digital screen and recorded. This procedure was repeated five times within intervals of 5 minutes. The force values were averaged for each mouse and plotted.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.1.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com). Values in the plots are presented as mean ± SEM. In all tests, means were considered significantly different if p ≤0.05. To compare the effect of sound level (dB) on the startle response amplitude between genotypes, a two way repeated measures ANOVA (RM two way-ANOVA) was performed (GraphPad Software, Inc. https://www.graphpad.com/guides/prism/latest/statistics/repeated_measures.htm). The factors considered in the RM two way-ANOVA were genotype, sound level, and genotype x sound level interaction. The same ANOVA procedure was applied to compare the effect of stimulus frequencies on ABR thresholds between genotypes, where the factors were genotype, frequency, and genotype x frequency interaction. In analyses of habituation (figure 6) responses were combined together into blocks. To compare differences of the effect of blocks of stimuli on the percentage of startle response between genotypes, the factors were: genotype, block, and genotype x block interaction. As RM two way-ANOVA tests with multiple measurements usually violate the sphericity assumption (Quinn and Keough, 2002), the method Geisser-Greenhouse sphericity correction was applied (GraphPad Software, Inc. https://www.graphpad.com/guides/prism/latest/statistics/stat_sphericity_and_compound_symmet.htm). This correction decreases the degrees of freedom and reduces the risk of a Type 1 error (Quinn and Keough, 2002). To compare differences between two groups, either a Student t-test or a Welch t-test was performed, as stated in the corresponding figure legends. When the sample sizes and/or the variances were different between groups, we applied a t-test with Welch’s correction. With this test the number of degrees of freedom tends to be smaller than (n1+n2-2) (Welch, 1938). To calculate the effect size (ES), we used the Cohen’s equation (Cohen, 1988), a statistical parameter that indicates the magnitude difference between WT and KO mice. In the corresponding figure legends we included the calculated ES of each experimental analysis. Effect sizes are expressed as Cohen’s d for the t-tests or as Cohen’s f for the ANOVA tests (Cohen, 1988).

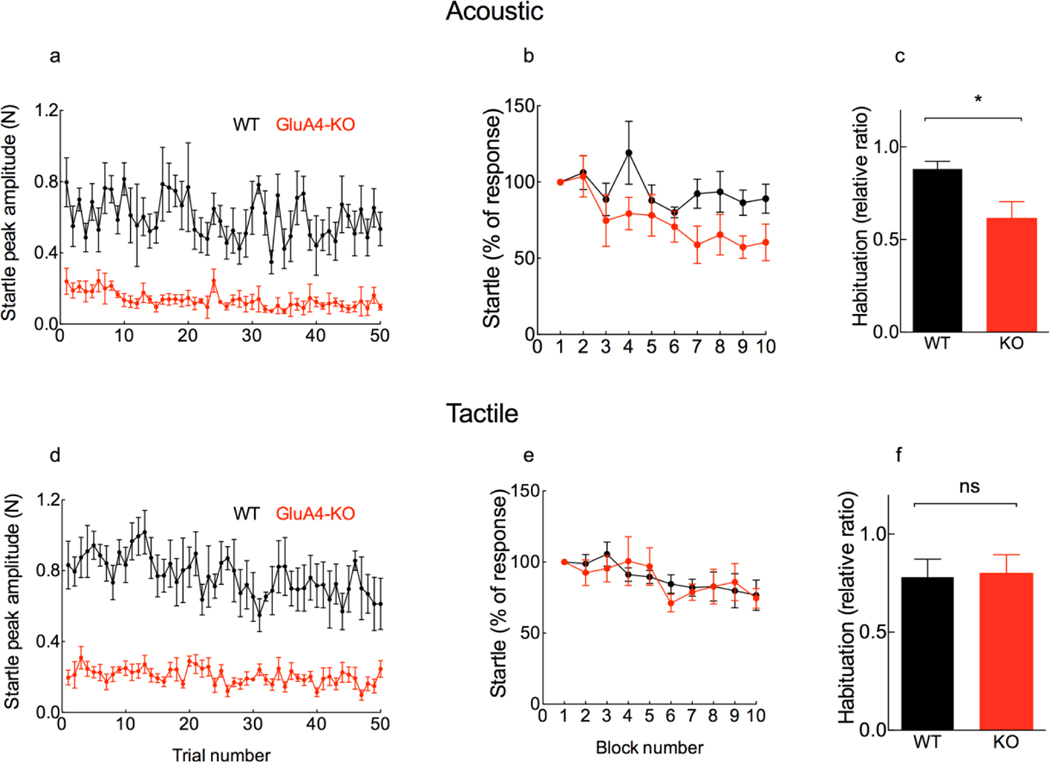

Figure 6. Lack of GluA4 affects short-term habituation of the ASR.

a, Mean maximum 1st peak amplitude (±SEM) of the ASR as a function of repeated acoustic stimulation (50 white noise pulses of 105 dB, 40 ms per pulse, with Inter-trial intervals of 20 s). b, To obtain the percentage change of the startle response (shown in b and e), the fifty trials from plots a and d, respectively, were split into blocks of five trials, and each block of five trials averaged for each mouse; the percentage of startle response in each block is relative to the first block. Mean percentage of the initial startle response is similar between genotypes (F(1,10)=3.5, p= 0.09; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 6 each genotype); there is a significant effect of block number (F(2.54,25.4)=3.49, p=0.03; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 6 each genotype; Cohen’s f=0.59); and there is no genotype x block interaction (F(9,90)=1.15, p=0.33; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 6 each genotype). c, To express habituation, the averaged amplitude of the last ten trials was expressed as a ratio to the averaged amplitude of the first five trials for each mouse, and the mean (±SEM) was plotted as a bar. Short-term habituation of the ASR is significantly increased in the GluA4-KO (0.61 ± 0.22 SD) as compared to WT (0.88 ± 0.10 SD) mice (t(10)=2.68, p= 0.02, unpaired t-test; n= 6 each genotype; Cohen’s d=1.6). d, Mean maximum 1st peak amplitude (±SEM) of the TSR as a function of repeated tactile stimulation (50 air puffs, 40 ms each, with Inter-trial intervals of 20s). e, Mean percentage of the initial startle response is similar between genotypes (F(1,12)=0.06, p= 0.8; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 7 each genotype); there is no significant effect of block number (F(2.77,33.3)=2.9, p=0.05); and there is no genotype x block interaction (F(9,108)=0.69, p=0.71; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 7 each genotype). f, Short-term habituation of the TSR (expressed as described in b above) is similar between genotypes (WT: 0.78 ± 0.25 SD; KO: 0.79 ± 0.29 SD) (t(12)=0.11, p= 0.91, unpaired t-test; n= 7 each genotype).

Immunofluorescence

Brain tissues of three WT and two GluA4-KO mice were processed for immunofluorescence. Mice were deeply anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (100 mg/kg each) and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) pH 7.2. Brains were post-fixed overnight in the same fixative and cryoprotected with 30% sucrose overnight, and then cryostat sectioned at a thickness of 30 μm. Sections were rinsed with PB and then incubated in blocking buffer, containing 10% normal goat serum, 1% BSA and 0.3% triton X-100 in PB, for 1 hour at room temperature. The primary antibodies, rabbit anti-GluA4 (2 μg/mL; Chemicon AB1508) or guinea pig anti-Calbindin (1:500; Synaptic Systems 214 004), were added to the sections and incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer. After rinsing well with blocking buffer, the sections were incubated with anti-species specific secondary antibodies, conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 488 or 568 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were visualized using Dapi. Images of immunostained sections were captured on an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with epi-fluorescence illumination (100W mercury burner) and CellSensDimension software for image acquisition (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Acoustic startle

The standard method to evaluate the startle response in mammals is to measure the amplitude of the startle waveform, which reflects the voltage output of the transducer (Davis, 1984). However, the quantification and analysis of the SR varies across laboratories. For instance, some researchers define the startle amplitude as the largest peak-to-peak voltage occurring within 30 ms (Carlson and Willott, 1998), 80 ms (Simons-Weidenmaier et al., 2006) or 200 ms (Cassella and Davis, 1986; Davis et al., 1982; Zhao and Davis, 2004) after the onset of the startle-stimulus. Others report the amplitude from the first positive peak to the following negative trough (e.g. Basavaraj and Yan, 2012; Typlt et al., 2013). This leads to difficulties in comparing results across laboratories.

The waveform generated with the equipment and software used in this study shows at least three prominent positive peaks in our recording window (Fig. 2a), and automatically measures the maximum positive value of the second peak. For our analyses we first plotted the amplitude of that peak as a function of sound level (Fig. 2b) and found that in the GluA4-KO mice the threshold for startle (defined as the sound intensity at which the startle amplitude is significantly higher than the discriminator criterion) is 105 dB, while in the WT the threshold is 85 dB (Fig. 2b arrows). The peak amplitudes are dramatically reduced at all the startle-eliciting sound levels in the GluA4-KO mice, as compared to WT mice (Fig. 2b). Nevertheless, it has been shown that only the first peak of that stereotyped waveform is associated with a startle response in mice (Grimsley et al, 2015). Our findings confirm this conclusion, as the second and third peaks appear even in the absence of a true startle (see magenta trace of Fig. 2c), indicating that the platform of our equipment oscillates after the mouse movement, hiding the non-startle trials (Grimsley et al., 2015 and present observations). Therefore, from now on we define the startle amplitude as the maximum positive value of the first peak after the onset of the startle-stimulus (arrowheads in 2c and 2d), since that peak corresponds to a downward movement (Grimsley et al., 2015) resulting from the extension of the forelimbs in rodents (Davis, 1984; Hoffman and Searle, 1968). Furthermore, the latency of the first peak in our study (Fig. 5c) is consistent with the ASR latency of 17.3 to 22.3 ms reported for mice (Grimsley et al., 2015).We considered the characteristics of the recording equipment to avoid including artifacts like oscillation in the analyses, and to rescue valuable information from the output waveform, such as latency and startle probability. The time window of our recordings was 100 ms, which captured an initial startle waveform and later secondary movements that were probably due to resonant characteristics of the system. We used an initial 50 ms window to exclude the secondary movements from the analyses.

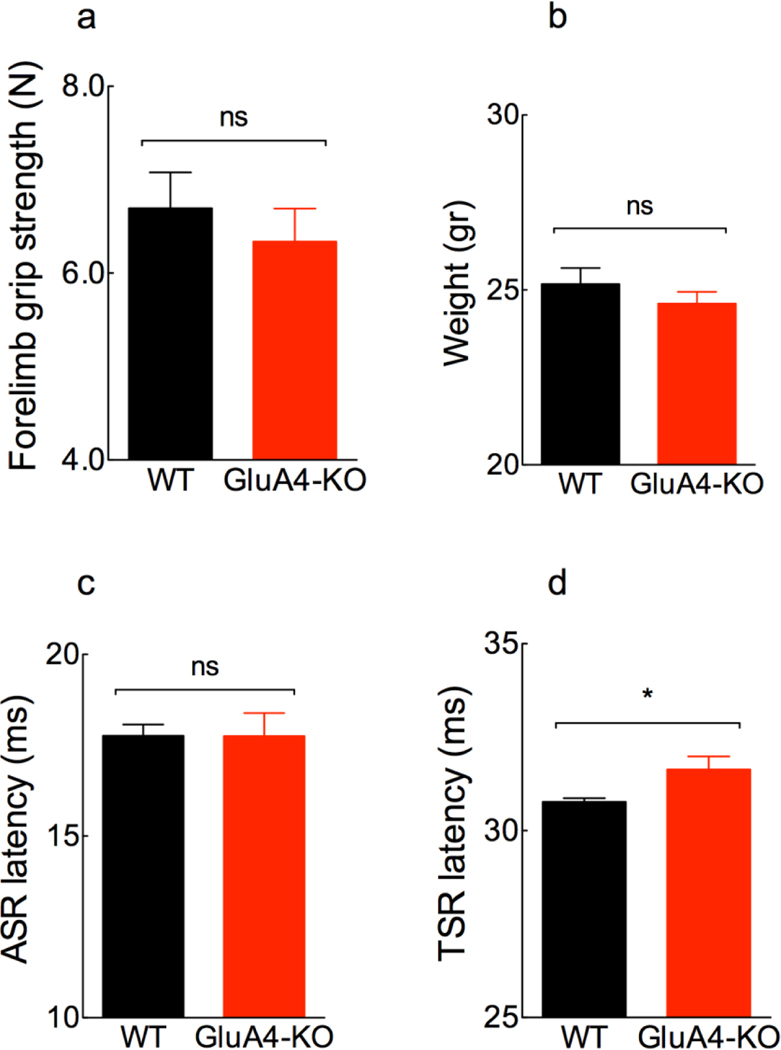

Figure 5. Deletion of GluA4 does not affect the motor component of the SR.

a, Mean forelimb grip strength is similar between WT (6.7 ± 1.2 SD) and KO (6.3 ± 1.2 SD) mice (t (18)= 0.68, p= 0.51, unpaired t-test; n= 9 WT, 11 KO). b, Mean body weight is similar between genotypes (WT: 25.2 ± 2.5 SD; KO: 24.6 ± 1.9 SD) (t (60)= 1.0, p= 0.32, unpaired t-test; n= 30 WT, 32 KO). c, Mean peak ASR latency is similar between genotypes (WT: 17.77 ± 0.74 SD; KO:17.75 ± 1.5 SD) (t (7.12)= 0.02, p= 0. 98, unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction; n= 6 each genotype). d, Mean peak TSR latency is significantly increased in the GluA4-KO (31.6 ± 0.9 SD) as compared to WT mice (30.8 ± 0.3 SD) (t (12)= 2.39, p= 0. 03, unpaired t-test; n= 7 each genotype; Cohen’s d=1.3).

Our analysis of the first peak revealed that several stimuli failed to elicit startle responses in the GluA4-KO mice; therefore, we calculated the response probability by separating the successful and unsuccessful trials from the startle waveforms (2c and 2d). If the amplitude of the first peak (arrowheads) exceeded the discriminator criterion (two standard deviations above the mean baseline), that was considered to be a successful response; the amplitudes of the successful responses were measured and averaged (Fig. 2f). We found that the percent of successful acoustic startle trials in the GluA4-KO mice is significantly reduced at all the intensities tested, as compared to WT mice (Fig. 2e). The amplitude of the successful acoustic startle trials in the GluA4-KO is also significantly reduced (Fig. 2f), as compared to WT mice. This indicates that the lack of GluA4 not only leads to reduced startle responses but also decreases the startle response probability.

Auditory processing

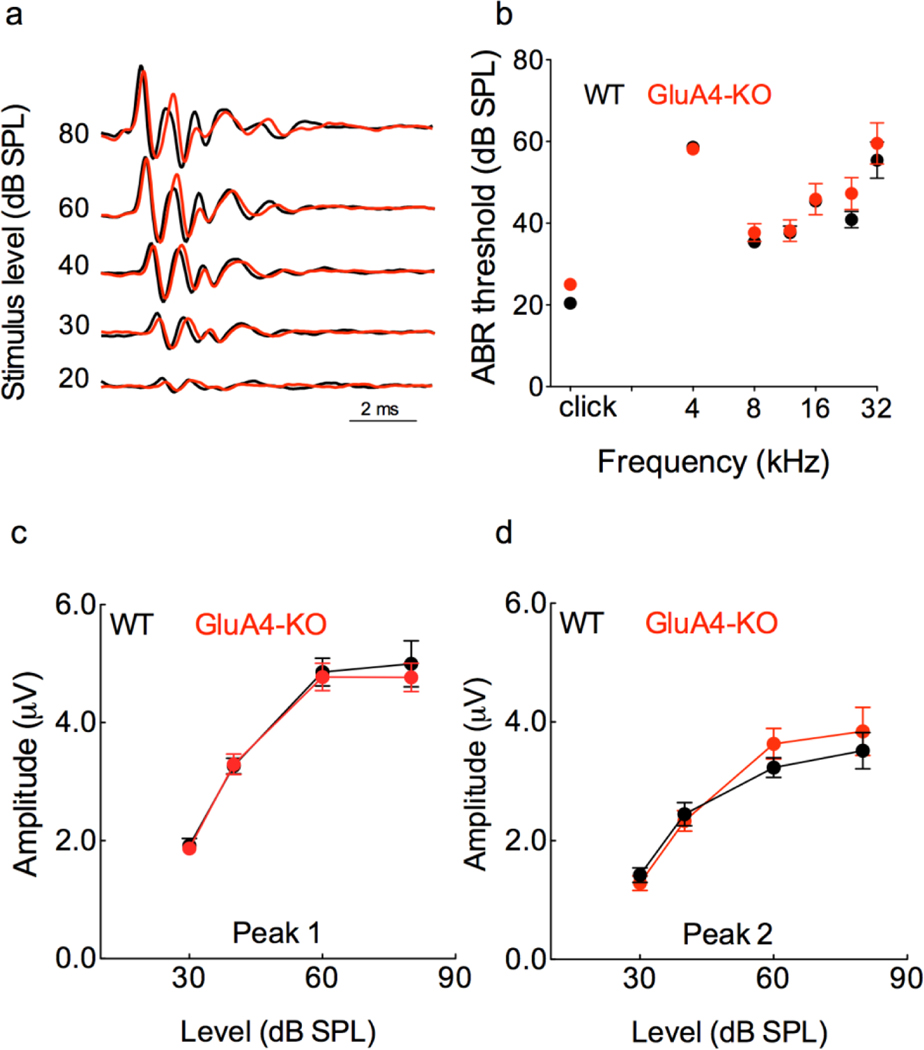

Since the threshold for startle in the GluA4-KO mice is increased by 20 dBs when compared to the WT mice (Fig. 2b), we measured auditory sensitivity by recording ABRs from WT and GluA4-KO mice. We found no differences in ABR thresholds between genotypes, neither for clicks nor for tones (Fig. 3a and 3b). This suggests that hearing sensitivity is normal in the absence of GluA4. To further evaluate auditory processing, we measured the amplitudes of peaks 1 and 2 (P1 and P2, respectively), discernible in all the traces from click-evoked ABRs (Fig 3a). We plotted peak amplitudes as a function of sound pressure level, and found that P1 and P2 are similar between genotypes (Fig. 3c and 3d). This suggests normal auditory processing in the auditory nerve and in the cochlear nucleus. Therefore, the reduced acoustic startle in the GluA4-KO mice is not a consequence of hearing loss or peripheral auditory dysfunction.

Figure 3. Lack of GluA4 does not affect auditory sensitivity.

a, Averaged ABR waveforms evoked with clicks from WT (black) and GluA4-KO (red) mice. b, Mean ABR thresholds (±SEM) are similar between genotypes (F(1,28) = 1.41, p= 0. 24; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 15 each genotype). There was an effect of stimulus frequency (F(2.8,78)=85.9, p< 0.0001; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 15 each genotype; Cohen’s f=1.7), and there was no genotype x frequency interaction (F(6,168)=0.59, p=0.74).c-d, Mean amplitude (±SEM) as a function of sound level (dB) for peaks 1 and 2 (P1 and P2) from click-evoked ABRs. Amplitudes of P1 and P2 are similar between genotypes (P1: F(1,26) = 0.13, p= 0.71; P2: F(1,26) = 0.20, p= 0.65; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 14 each genotype). There was an effect of sound level (P1: F(2.01,52.3)=139.5, p< 0.0001; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 14 each genotype; Cohen’s f=2.3; P2: F(2.01,52.3)=81, p< 0.0001; RM two way-ANOVA; n= 14 each genotype; Cohen’s f=2.3), and there was no genotype x sound level interaction (P1: F(3,78)=0.2, p=0.89; P2: F(3,78)=1.4, p=0.24).

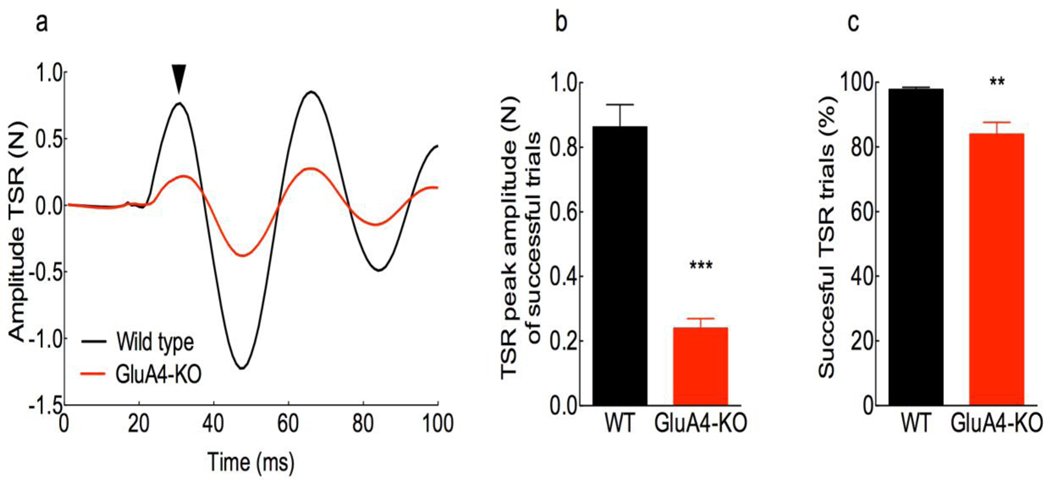

Tactile startle

Another startle modality that is activated independently of the acoustic is the tactile startle pathway, and both converge at the PnC neurons (Pilz et al., 2004; Yeomans et al., 2002). We hypothesized that if the deletion of GluA4 affects only the acoustic SR, the tactile SR should be normal in GluA4-KO mice. We evaluated the 1st peak (Fig. 4a arrowhead) startle amplitude in response to ten air puffs, and found that the tactile startle amplitude of successful trials (Figs. 4a and 4b) was significantly reduced in the GluA4-KO (mean=0.24, SD= 0.08) as compared to WT mice (mean=0.86, SD=0.19). Additionally, the percent of successful tactile startle in the GluA4-KO mice (mean=83.9,SD=10.4) was significantly decreased as compared to WT mice (mean=97.8, SD=2.0) (Fig. 4c). These results show that GluA4 is important for both acoustic and tactile SR pathways.

Figure 4. Deletion of GluA4 reduces the tactile startle response (TSR).

a, Representative TSR waveform from a WT (black) and a GluA4-KO (red) mouse, elicited with air puffs. Such waveforms were used to determine the amplitude of the 1st peak (arrowhead) and the percentage of successful trials. b, Mean amplitude of the 1st peak in successful trials of the TSR is significantly reduced in KO (0.240 ± 0.08 SD) as compared to WT mice (0.86 ± 0.19 SD) (t (9.49)= 8.21, p<0.0001, unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction; n= 8 each genotype; Cohen’s d=4.1). c, Mean percentage of successful trials of the TSR is significantly reduced in the GluA4-KO (83.9 ± 10.4 SD) as compared to WT mice (97.8 ± 2.0 SD) (t (7.47)= 3.68, p=0.007, unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction; n= 9 WT, 8 KO; Cohen’s d=2.1).

Motor function

The fact that both acoustic- and tactile-elicited startle responses are significantly decreased in the absence of GluA4 prompted us to evaluate the gross motor function of the startle pathway, which is common to both sensory modalities. One of the earliest motor responses in the whole-body startle of rodents is the extension of the forelimbs (Davis, 1984). To assess motor function in the forelimb muscles, we measured forelimb grip strength in WT and GluA4-KO mice. We found that the grip strength is similar in WT and GluA4-KO mice (Fig. 5a). Since the output force depends on the size of the mouse, we compared their body weight, and found it to be comparable between genotypes (Fig. 5b). These results show that the lack of GluA4 does not lead to changes in forelimb muscle strength or body weight.

Since the SR involves a fast motor response (Yeomans et al., 2002), we evaluated the latencies of the SR to assess the speed of the response in both WT and GluA4-KO mice. Generally, when amplitude decreases in behavioral response tests the latency increases (Pilz and Schnitzler, 1996). Since we found decreases in the amplitude of both the ASR and TSR, we expected to find increased latencies for both responses. However, we observed that latencies of the ASR were similar between genotypes (Fig. 5c), while the TSR latency is slightly increased in the GluA4-KO as compared to WT mice (Fig. 5d). This indicates a slightly slower startle response in the absence of GluA4 in the tactile pathway. The fact that only the tactile but not the acoustic startle response is delayed suggests that GluA4 is involved in the TSR before multimodal integration in the PnC, probably at the level of the Pr5 neurons. However, due to the limited number of mice available for these observations, this conclusion must remain tentative and will not be discussed further.

Short-term habituation

We evaluated short-term habituation of the acoustic and tactile startle as a means to assess the sensory function of the SR pathway (Simons-Weidenmaier et al., 2006; Valsamis and Schmid, 2011). Habituation is defined as the decreased behavioral response to a specific stimulus that is presented repeatedly (Rankin et al., 2009). Short-term habituation of the startle is a property of the baseline startle pathway (Davis, 1984) that is caused by synaptic depression of the acoustic (CRNs) or the trigeminal (Pr5) sensory axon terminals (Pilz et al., 2004; Simons-Weidenmaier et al., 2006) that synapse on the PnC sensorimotor neurons (Lingenhöhl and Friauf, 1992, 1994; Schmid et al., 2003; Yeomans and Cochrane, 1993).

If habituation occurs, reduced startle amplitude is expected after repeated auditory or tactile stimulation. Therefore, we presented fifty consecutive white noise stimuli (105 dB, 40 ms per stimulus, with an interval of 20 s between stimuli) or fifty consecutive air puffs (40 ms per puff with an interval of 20 s between stimuli) to WT and GluA4-KO mice.

To compare short-term habituation curves between WT and GluA4-KO mice, we plotted the first peak amplitude of successful startle responses (Figs. 6a and 6d). To evaluate short-term habituation, the fifty trials plotted in 6a and 6d were split into blocks, each consisting of five trials that were averaged for each mouse. Each block was then divided by the first block to obtain the percentage of the initial startle response (Figs. 6b and 6e). By comparing these habituation curves, we found that the mean percentage of the startle reflex is similar between genotypes for both acoustic (Fig. 6b) and tactile (Fig. 6e) modalities. With successive trials, however, the ASR is slightly reduced in the GluA4-KO as compared with WT mice (Fig 6b). To further express short-term habituation, we plotted the ratio of the averaged amplitude of last ten trials-to-first five trials of each mouse (Figs. 6c and 6f). With this approach we found that short-term habituation of the TSR is similar between genotypes (Fig. 6f), while short-term habituation of the ASR is significantly increased in the GluA4-KO as compared to WT mice (Fig. 6c). In this study it was difficult to discern habituation, because our GluA4-KO mice already had a decreased response amplitude and fewer successful responses (Figs. 2 and 4). However, comparing initial responses with final responses in the same mice allowed us to detect habituation. The results suggest that the lack of GluA4 increased short-term habituation of the acoustic startle reflex. However, due to the limited number of mice available for these observations, this conclusion must remain tentative and will not be discussed further.

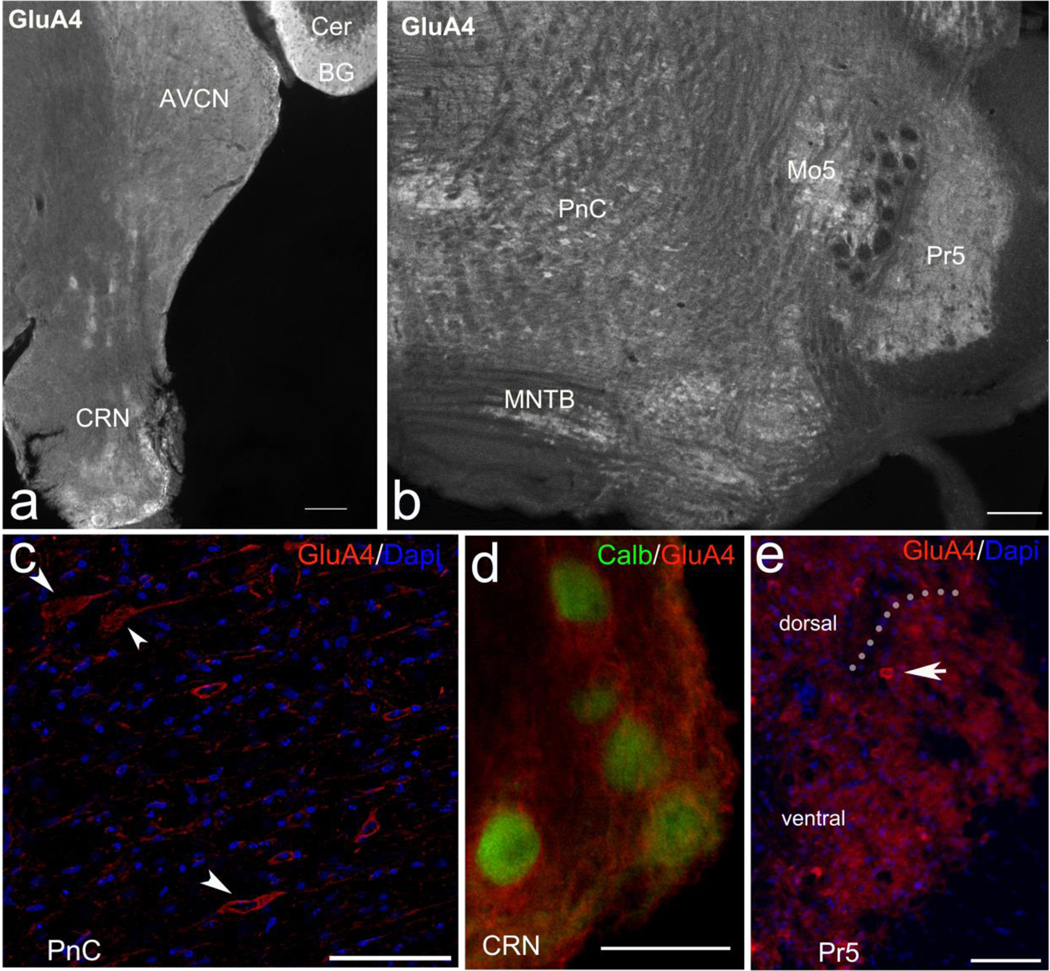

Immunolocalization of GluA4 in the SR pathway

Since both acoustic and tactile SR are noticeably reduced in the GluA4-KO mice, we assessed the immunolocalization of GluA4 in brainstem nuclei involved in the SR pathway. We used anti-GluA4 antibody on brainstem sections from WT mice, and used the cerebellum of the same brainstem section as a positive control. The expression of GluA4 in the cerebellum has been widely studied using immunofluorescence (Shevtsova and Leitch, 2012). We used brainstem sections from GluA4-KO mice as a negative control, and found no GluA4 immunolabeling (data not shown). In agreement with previous reports (Douyard et al., 2007; Saab et al., 2012), we found strong immunolabeling of GluA4 in the Bergmann glia of the cerebellum (Fig. 7a). Within the auditory nerve root, as previously shown (Gómez-Nieto et al., 2008), we found immunoreactivity to GluA4 mainly on glial cells around the CRN (Fig. 7a and 7d). In the Pr5, GluA4 is immunolocalized mainly in the neuropil and in some small cell bodies (Fig. 7b and 7e). In the PnC, GluA4 is located mainly in the cell bodies of large neurons (Fig. 7b and 7c). Our results support the idea that neurons common to ASR and TSR, probably those in the PnC, need GluA4 to mediate full acoustic and tactile startle responses.

Figure 7. GluA4 is localized in the primary SR pathway.

a, Immunofluorescence of GluA4 is in the cerebellum (Cer) labeling the Bergmann glia (BG), the anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN) and in the cochlear root nucleus (CRN). b, GluA4 is also localized in the caudal pontine reticular nucleus (PnC), the motor nucleus of the trigeminal nerve (Mo5), the principal sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve (Pr5) and the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB). c, The cell bodies of PnC giant neurons (arrowheads) are immunolabeled with GluA4. d, GluA4 in the CRN is observed surrounding calbindin (calb) labeled cell bodies. e, GluA4 in the Pr5 is mainly in the neuropil and in some small cell bodies (arrow pointing to one cell); doted line divides the Pr5 into the dorsal (above) and the ventral (below) parts of the nucleus. Scale bars: a, 200 μm; b, 100 μm; c-e, 50 μm.

Discussion

The present study shows that deletion of GluA4 leads to a pronounced decrease of amplitude and probability of successful acoustic and tactile startle responses. The reduced ASR in the GluA4-KO mice is not a consequence of hearing loss or peripheral auditory dysfunction, as the auditory thresholds and amplitudes of P1 and P2 of the ABR are similar between genotypes. The fact that both, acoustic and tactile startle responses, are reduced in the absence of GluA4 indicates that this receptor subunit is critical at a common region within the acoustic and tactile startle pathways. Since the final common path of both startle modalities is the motor pathway, we assessed grip strength to evaluate motor function, and found it to be similar between genotypes, ruling out gross motor dysfunction caused by the lack of GluA4.

The next common upstream factor in the acoustic and tactile startle modalities is the population of giant neurons in the caudal pontine reticular nucleus, where the sensory signals converge to be integrated and transmitted to cranial and spinal motor neurons (Davis, 1984; Lingenhöhl and Friauf, 1994; Yeomans et al., 2002). Therefore, we assessed the immunolocalization of GluA4 in the PnC neurons.

In view of the GluA4 immunoreactivity of the PnC neurons, we suggest that the GluA4 subunit acts at the level of the PnC neurons, an obligatory relay for both the acoustic and the tactile sensory modalities (Fig. 1). It is possible that the lack of GluA4 in the PnC prevents the startle signal coming from the CRN and the Pr5 to be integrated in the PnC neurons, as AMPARs are generally located at the postsynaptic density of glutamatergic synapses (Diering and Huganir, 2018; Rubio and Wenthold, 1997). However, we cannot completely exclude a role of GluA4 in the synapses of PnC axons on motor neurons involved in startle reflex, as AMPA receptors are critical mediators of signal transmission along the SR pathway (Krase et al., 1993; Ebert and Koch, 1992) and GluA4 is also present in the spinal cord (Tachibana et al., 1994).

To elicit an ASR, the synchronized onset responses in the PnC neurons are necessary to promote summed activation of motor neurons (Lingenhöhl and Friauf, 1994). Since the GluA4 AMPAR subunit is present in the PnC neurons (Fig. 7c) and its presence produces currents with very fast kinetics (Geiger et al., 1995; Mosbacher et al., 1994), it is plausible to propose that GluA4 is necessary to elicit fast synaptic responses in the PnC neurons which would subsequently activate motor neurons to elicit a full startle response. This is supported by the observation that in the absence of GluA4 there is a dramatic decrease of acoustic and tactile SR amplitudes, and the amplitude of the SR is correlated with the magnitude of the response in the PnC neurons (Koch et al., 1992; Wu et al., 1988). Additionally, the decreased probabilities of successful acoustic and tactile startle responses found in the GluA4-KO mice may come from failures of synaptic transmission in the PnC, as AMPARs allow high fidelity signal transmission (Greger et al., 2017) and GluA4 is necessary in some specialized synapses in the brainstem to facilitate faithful neurotransmission (Yang et al., 2011).

We conclude that deletion of the GluA4 subunit of the AMPAR affects the transmission of sensory signals from acoustic and tactile pathways to the motor component of the startle reflex, and that the GluA4 subunit is required for the full response and for reliable elicitation of the startle response.

Highlights.

Amplitude of acoustic and tactile startle response is decreased in GluA4-KO mice

The lack of GluA4 leads to reduced startle probability

Reduced SR is not a consequence of auditory or motor dysfunction

GluA4 is immunolocalized in the CRN, Pr5 and PnC

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (grant DC013048). We are grateful to: Cai Hou-Ming for maintaining the mouse colony and genotyping; Laura Miller for introducing SGH to the use of the startle equipment; Brian Brockway for helpful technical discussions; Karl Kandler for helpful discussions of preliminary results; Srivartun Sadagopan for advice with MATLAB programming; Steven Potashner for proof reading and help with English; Alejandro Frias-Villegas for advise with statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Author statement

We, the authors, certify that we participated substantially in the study “Role of GluA4 in the acoustic and tactile startle responses” and wrote the submitted manuscript. This manuscript has not been submitted to any other journal than in Hearing Research. We agree to take public responsibility for the contents of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Basavaraj S, Yan J, 2012. Prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle reflex as a function of the frequency difference between prepulse and background sounds in mice. PLoS One 7 (9): e45123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg WK, Balaban MT 1999. Startle elicitation: stimulus parameters, recording techniques, and quantification. In: Startle modification: Implications for neuroscience, cognitive science, and clinical science. Eds. Dawson ME, Schell AM, Bohmelt AH Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal TD, Cuthbert BN, Filion DL, Hackley S, Lipp OV, van Boxtel A. 2005. Committee report: Guidelines for human startle eyeblink electromyographic studies. Psychophysiology 42(1): 1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson S, Willott JF, 1998. Caudal pontine reticular formation of C57BL/6J mice: responses to startle stimuli, inhibition by tones, and plasticity. Journal of Neurophysiology 79 (5): 2603–2614. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassella JV, Davis M, 1986. The design and calibration of a startle measurement system. Physiology and Behavior 36 (2): 377–383. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Csomor PA, Yee BK, Vollenweider FX, Feldon J, Nicolet T, Quednow BB, 2008. On the influence of baseline startle reactivity on the indexation of prepulse inhibition. Behavioral Neuroscience 122 (4): 885–900. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Gendelman DS, Tischler MD, Gendelman PM, 1982. A primary acoustic startle circuit: lesion and stimulation studies. Journal of Neuroscience 2 (6): 791–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-06-00791.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, 1984. The mammalian startle response. In: Neural mechanisms of startle behavior. Ed. Eaton RC Springer Science & Business Media, New York. pp. 287–351. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Walker DL, Lee Y, 1999. Neurophysiology and neuropharmacology of startle and its affective modulation. In: Startle modification: Implications for neuroscience, cognitive science, and clinical science. Eds. Dawson ME, Schell AM, Bohmelt AH Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- De Pitta M, Volman V, Berry H, Ben-Jacob E, 2011. A tale of two stories: astrocyte regulation of synaptic depression and facilitation. Plos Computational Biology 7 (12): e1002293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diering GH, Huganir RL, 2018. The AMPA receptor code of synaptic plasticity. Neuron 100 (2): 314–329. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douyard J, Shen L, Huganir RL, Rubio ME, 2007. Differential neuronal and glial expression of GluR1 AMPA receptor subunit, and the scaffolding proteins SAP97 and 4.1N during rat cerebellar development. Journal of Comparative Neurology 502 (1): 141–156. doi: 10.1002/cne.21294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert U, Koch M, 1992. Glutamate receptors mediate acoustic input to the reticular brain stem. Neuroreport 3 (5): 429–432. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199205000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. 2007. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods 39(2): 175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendt M, Koch M, 2013. Translational value of startle modulations. Cell and Tissue Research 354 (1): 287–295. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Montoya J, Buendia I, Martin YB, Egea J, Negredo P, Avendaño C, 2016. Sensory input-dependent changes in glutamatergic neurotransmission related genes and proteins in the adult rat trigeminal ganglion. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 28 (9): 132. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Hernández S, Abe M, Sakimura K, Rubio ME, 2017. Impaired auditory processing and altered structure of the endbulb of Held synapse in mice lacking the GluA3 subunit of AMPA receptors. Hearing Research 344: 284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner SM, Takamiya K, Xia J, Suh JG, Johnson R, Yu S, Huganir RL, 2005. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptor plasticity is mediated by subunit-specific interactions with PICK1 and NSF. Neuron 45 (6): 903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner SM, Trussell LO, Oertel D, 1999. Time course and permeation of synaptic AMPA receptors in cochlear nuclear neurons correlate with input. Journal of Neuroscience 19 (20): 8721–8729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08721.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger JR, Melcher T, Koh DS, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH, Jonas P, Monyer H, 1995. Relative abundance of subunit mRNAs determines gating and Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors in principal neurons and interneurons in rat CNS. Neuron 15 (1): 193–204. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Nieto R, Horta-Junior JA, Castellano O, Herrero-Turrion MJ, Rubio ME, López DE, 2008. Neurochemistry of the afferents to the rat cochlear root nucleus: possible synaptic modulation of the acoustic startle. Neuroscience 154 (1): 51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger IH, Watson JF, Cull-Candy SG, 2017. Structural and functional architecture of AMPA-type glutamate receptors and their auxiliary proteins. Neuron 94 (4): 713–730. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsley CA, Longenecker RJ, Rosen MJ, Young JW, Grimsley JM, Galazyuk AV, 2015. An improved approach to separating startle data from noise. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 253: 206–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JM, Warr WB, 1962. A study of the cochlear nuclei and ascending auditory pathways of the medulla. Journal of Comparative Neurology 119: 341–379. doi: 10.1002/cne.901190306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KR. 1979. Auditory brainstem volume-conducted responses: origins in the laboratory mouse. Journal of the American Auditory Society 4 (5): 173–8. PMID: 511644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HS, 1999. A historical note on the “discovery” of startle modification. In: Startle modification: Implications for neuroscience, cognitive science, and clinical science. Eds. Dawson ME, Schell AM, Bohmelt AH Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HS, Searle JL, 1968. Acoustic and temporal factors in the evocation of startle. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America 43 (2): 269–282. doi: 10.1121/1.1910776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C, Petralia RS, Vu T, Wenthold RJ, 1993. Expression of AMPA-selective glutamate receptor subunits in morphologically defined neurons of the mammalian cochlear nucleus. Journal of Neuroscience 13 (5): 1932–1946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-01932.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison JR, 2001. The acoustic startle response: Reflex elicitation and reflex modification by preliminary stimuli. In: Willott JF Handbook of Mouse Auditory Research: From Behavior to Molecular Biology. Ed. Willot JF. Boca Raton. pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jewett DL, Romano MN, Williston JS. 1970. Human auditory evoked potentials: possible brain stem components detected on the scalp. Science 13; 167 (3924):1517–8. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3924.1517. PMID: 5415287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Herbert H, 1991. Auditory projections from the cochlear nucleus to pontine and mesencephalic reticular nuclei in the rat. Brain Research 562 (2): 230–242. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90626-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Lingenhöhl K, Pilz PK, 1992. Loss of the acoustic startle response following neurotoxic lesions of the caudal pontine reticular formation: possible role of giant neurons. Neuroscience 1992 49 (3): 617–25. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90231-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Schnitzler HU, 1997. The acoustic startle response in rats--circuits mediating evocation, inhibition and potentiation. Behavioral Brain Research 89 (1–2): 35–49. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)02296–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, 1999. The neurobiology of startle. Progress in Neurobiology 59 (2): 107–128. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krase W, Koch M, Schnitzler HU, 1993. Glutamate antagonists in the reticular formation reduce the acoustic startle response. Neuroreport 4 (1): 13–16. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingenhöhl K, Friauf E, 1992. Giant neurons in the caudal pontine reticular formation receive short latency acoustic input: an intracellular recording and HRP-study in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology 325 (4): 473–492. doi: 10.1002/cne.903250403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingenhöhl K, Friauf E, 1994. Giant neurons in the rat reticular formation: a sensorimotor interface in the elementary acoustic startle circuit? Journal of Neuroscience 14 (3 Pt 1): 1176–1194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01176.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López DE, Saldaña E, Nodal FR, Merchán MA, Warr WB, 1999. Projections of cochlear root neurons, sentinels of the rat auditory pathway. Journal of Comparative Neurology 415 (2): 160–174. PMID: 10545157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher JR, Kiang NY. 1996. Generators of the brainstem auditory evoked potential in cat. III: Identified cell populations. Hearing Research 93(1–2): 52–71. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00200-6. PMID: 8735068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchán MA, Collia F, López DE, Saldaña E, 1988. Morphology of cochlear root neurons in the rat. Journal of Neurocytology 17 (5): 711–725. doi: 10.1007/BF01260998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miserendino MJ, Davis M, 1993. NMDA and non-NMDA antagonists infused into the nucleus reticularis pontis caudalis depress the acoustic startle reflex. Brain Research 623 (2): 215–222. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91430-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosbacher J, Schoepfer R, Monyer H, Burnashev N, Seeburg PH, Ruppersberg JP, 1994. A molecular determinant for submillisecond desensitization in glutamate receptors. Science 266 (5187): 1059–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.7973663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilz PK, Schnitzler HU. 1996. Habituation and sensitization of the acoustic startle response in rats: amplitude, threshold, and latency measures. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 66 (1): 67–79. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilz PK, Carl TD, Plappert CF, 2004. Habituation of the acoustic and the tactile startle responses in mice: two independent sensory processes. Behavioral Neuroscience 118 (5): 975–983. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli E, Angrilli A, 2015. Greater general startle reflex is associated with greater anxiety levels: a correlational study on 111 young women. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 9: 10. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn GP. and Keoug MJ. 2002. Experimental design and data analysis for biologist. Cambridge University Press. p 318. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin CH, Abrams T, Barry RJ, Bhatnagar S, Clayton DF, Colombo J, Copola G, Geyer MA, Glanzman DL, Marsland S, McSweeney FK, Wilson DA, Wu C-F, Thompson RF, 2009. Habituation revisited: an updated and revised description of the behavioral characteristics of habituation. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 92 (2): 135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio ME, Wenthold RJ, 1997. Glutamate receptors are selectively targeted to postsynaptic sites in neurons. Neuron 18 (6): 939–950. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saab AS, Neumeyer A, Jahn HJ, Cupido A, Boele H-J, Simek AAM, Scheller A, Le Meur K, Götz M, Monyer H, Sprengel R, Rubio ME, de Zeeuw C, Deitmer JW, Kirchhoff F, 2012. Bergmann glial AMPA receptors are required for fine motor coordination. Science 337 (6095): 749–753. doi: 10.1126/science.1221140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N, Iwaki A, Aramaki T, Takao K, Kura S, Tsuzuki T, Kawakami R, Ito I, Kitamura T, Sugiyama H, Miyakawa T, Fukumaki Y, 2010. Comprehensive behavioural study of GluR4 knockout mice: implication in cognitive function. Genes Brain and Behavior 9 (8): 899–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid S, Guthmann A, Ruppersberg JP, Herbert H, 2001. Expression of AMPA receptor subunit flip/flop splice variants in the rat auditory brainstem and inferior colliculus. Journal of Comparative Neurology 430 (2): 160–171. doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid S, Simons NS, Schnitzler HU, 2003. Cellular mechanisms of the trigeminally evoked startle response. European Journal of Neuroscience 17 (7): 1438–1444. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Weidenmaier NS, Weber M, Plappert CF, Pilz PK, Schmid S, 2006. Synaptic depression and short-term habituation are located in the sensory part of the mammalian startle pathway. BMC Neuroscience 7: 38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair D, Oranje B, Razak KA, Siegel SJ, Schmid S, 2017. Sensory processing in autism spectrum disorders and Fragile X syndrome-From the clinic to animal models. Neuroscience and Bioehavioral Reviews 76 (Pt B): 235–253. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevtsova O, Leitch B, 2012. Selective loss of AMPA receptor subunits at inhibitory neuron synapses in the cerebellum of the ataxic stargazer mouse. Brain Research 1427: 54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidl S, Faerman P, Li L, Yeomans JS, 2004. Kynurenate in the pontine reticular formation inhibits acoustic and trigeminal nucleus-evoked startle, but not vestibular nucleus-evoked startle. Neuroscience 126 (1): 127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M, Wenthold RJ, Morioka H, Petralia RS, 1994. Light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical localization of AMPA-selective glutamate receptors in the rat spinal cord. Journal of Comparative Neurology 344(3): 431–54. doi: 10.1002/cne.903440307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd KJ, Darabid H, Robitaille R, 2010. Perisynaptic glia discriminate patterns of motor nerve activity and influence plasticity at the neuromuscular junction. Journal of Neuroscience 30: 11870–11882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3165-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Typlt M, Mirkowski M, Azzopardi E, Ruettiger L, Ruth P, Schmid S, 2013. Mice with deficient BK channel function show impaired prepulse inhibition and spatial learning, but normal working and spatial reference memory. PLoS One 8 (11): e81270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsamis B, Schmid S, 2011. Habituation and prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle in rodents. Journal of Visualized Experiments 55: e3446. doi: 10.3791/3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch BL 1938. The significance of the difference between two means when the population variances are unequal. Biometrika 29 (3/4): 350–362. [Google Scholar]

- Wu MF, Suzuki SS, Siegel JM, 1988. Anatomical distribution and response patterns of reticular neurons active in relation to acoustic startle. Brain Research 457 (2): 399–406. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90716-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, Aitoubah J, Lauer AM, Nuriya M, Takamiya K, Jia Z, May BJ, Huganir RL, Wang Y, 2011. GluA4 is indispensable for driving fast neurotransmission across a high-fidelity central synapse. Journal of Physiology 589 (17): 4209–4227. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.208066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates SK, Brown WF. 1981. Light-stimulus-evoked blink reflex: methods, normal values, relation to other blink reflexes, and observations in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 31 (3): 272–81. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans JS, Li L, Scott BW, Frankland PW, 2002. Tactile, acoustic and vestibular systems sum to elicit the startle reflex. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 26 (1): 1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans JS, Cochrane KA, 1993. Collision-like interactions between acoustic and electrical signals that produce startle reflexes in reticular formation sites. Brain Research 617 (2): 320–328. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Davis M, 2004. Fear-potentiated startle in rats is mediated by neurons in the deep layers of the superior colliculus/deep mesencephalic nucleus of the rostral midbrain through the glutamate non-NMDA receptors. Journal of Neuroscience 24 (46): 10326–10334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2758-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]