Abstract

We have developed a system for rapid typing of adenoviruses (Ads) based on a combination of PCR and restriction endonuclease (RE) digestion (PCR-RE digestion). Degenerated consensus primers were designed, allowing amplification of DNA from all 51 human Ad prototype strains and altogether 44 different genome variants of Ad serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 11, 19, 40, and 41. The 301-bp amplimer of 22 prototype strains representing all six subgenera and the genome variant was selected as a target for sequencing to look for subgenus and genome type variabilities. The sequences obtained were used to facilitate the selection of specific REs for discrimination purposes in a diagnostic assay by following the concept of cleavage or noncleavage of the 301-bp amplimer. On the basis of these results, a flowchart was constructed, allowing identification of subgenus B:2 and D serotypes and almost complete distinction of subgenus A, B:1, C, E, and F serotypes. Application of the PCR-RE digestion system to clinical samples allowed typing of 34 of 40 clinical samples positive for Ad. The genome type determined by this method was identical to that obtained by traditional RE typing of full-length Ad DNA. The remaining six samples were positive only after a nested PCR. Therefore, to reduce the risk of false-negative results, samples scored negative by the PCR-RE digestion system should be evaluated by the described nested PCR. Used in combination, the PCR-RE digestion method and the nested PCR provide a reliable and sensitive system that can easily be applied to all kinds of clinical samples when rapid identification of adenoviruses is needed.

The 51 different serotypes of human adenoviruses (Ads) are classified into six subgenera (subgenera A to F) on the basis of several biochemical and biophysical criteria (33, 49). Typing of Ads has so far mainly been of epidemiological interest. However, the improved knowledge about the differences in virulence among the several types has increased the medical value of typing. Cases of severe acute respiratory illness and also febrile illness with cardiopulmonary failure in infants and young children have been described (9, 30). These syndromes have frequently been associated with subgenus B Ads, preferentially genome variants of Ad type 7, with a high rate of mortality. In adults Ad serotype 2 infections have been shown to be important in the pathogenesis of left-ventricle failure (34). Ads are also among the agents that take advantage of an impaired or destroyed immune system to set up persistent and generalized infections in the immunocompromised host, infections that sometimes result in death (20).

Diagnosis of Ad infections is currently based on virus isolation in cell culture, antibody studies, or antigen detection by immunofluorescence (50). However, the need for rapid and sensitive detection methods has led to PCR being the most well established among all other methods. Primer systems for detection of Ads in general have frequently been used during the last 10 years (5, 6, 10, 31, 32, 35). Ad serotyping is based on neutralization or hemagglutination inhibition (17), but it can also be done by sequencing (29, 44). Genome typing can be done by restriction endonuclease (RE) analysis of full-length Ad DNA (2, 47) and with subgenus- or type-specific PCR primers (5, 24, 35, 37, 38). Recently, different methods have suggested how RE analysis and PCR can be combined to facilitate the typing procedure (7, 24, 39, 45). However, these methods have been incomplete or limited, with results sometimes difficult to interpret. This prompted us to develop a more extensive PCR-RE digestion typing method with a simple and clear-cut final readout. On the basis of hexon sequence data, we have developed new primers corresponding to a conserved region of the hexon gene upstream of the surface loop l1. The sequences of the Ad products framed by these primers were heterogeneous enough to allow discrimination between subgenera and even between serotypes by RE cleavage. We describe here a flowchart of RE digestions that can be used with nonnested PCR products for typing of human Ads. This typing system can be valuable when it is of importance to exclude types with more pronounced virulence, such as the members of subgenus B and Ad type 2 (Ad2) of subgenus C, but also Ad31 of subgenus A, which have frequently been isolated from immunocompromised hosts (20). In addition, the flowchart offers further possibilities for discrimination of more virulent genome variants of types 3 and 7 from among prototype strains. The method is intended for characterization of Ads both in clinical samples and in cell culture fluids.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Virus strains.

All prototype strains except those of Ad16, Ad40, Ad41, and Ad48 to Ad51 were originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The prototype strain of Ad16 was a gift from R. Wigand, Homburg, Germany. Ad40 reference strain Hovi-X and Ad41 prototype strain Tak were originally characterized at Bilthoven, The Netherlands (12). D. Schnurr of the Viral and Rickettsial Disease Laboratory, Berkeley, Calif., kindly donated strains of Ad48 and Ad49 (40). Candidate Ad strains of Ad50 and Ad51 (13) were kindly donated by J. C. deJong, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. The genome variants Ad1D7, Ad1D10, Ad2D5, Ad2D6, Ad2D7, Ad2D25, Ad2D36, Ad2D63, and Ad5D38, classified by the system of Adrian et al. (1), together with Ad7b, Ad7c, Ad7h, Ad7i, and Ad7j, were kindly donated by A. Kajon (22, 23, 30). Ad genome variants 3a, 3a2, 3c, and 3d (28), 4a, 4a1, 4b, 4p1, 4p2, and 4p3 (26), and 11a, 11b, and 11c (27) were kindly donated by Q. G. Li, Umeå, Sweden. Ad19a was described by Wadell and de Jong (48). Genome variants of Ad40 (D2, D5, D9, and D11) and Ad41 (D2, D6, D10, D11, D12, D13, D14, D15, D18, D22, and D24), classified by van der Avoort et al. (46), were kindly donated by Alistair Kidd, Umeå, Sweden. Ad41 strain D389 was described by Allard et al. (4).

Viral isolation.

Ad isolates were obtained by inoculation of tubes of A549 cells or 293 cells (Ad40 and Ad41) with prototype strains or clinical specimens. Cells were grown in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, glutamine, and antibiotics and maintained with Dulbecco's minimum essential medium supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum. Stocks of each virus isolate were grown in the cells and kept frozen at −70°C for further analysis.

DNA extraction.

Each isolate was used to inoculate confluent monolayers of A549 or 293 cells in 75-cm2 plastic flasks. When an extensive cytopathic effect was evident (48 to 72 h postinfection), intracellular full-length viral DNA was extracted as described by Shinagawa et al. (42). DNA to be used in PCR and PCR-RE analysis was purified by the QIAamp Blood Mini kit protocol (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany).

Clinical samples.

Forty specimens confirmed to be Ad positive by cell culture, immunofluorescense, or PCR in routine diagnostic work during the period from November 1994 to April 1995 were included in a retrospective study. Materials analyzed included 13 stool samples, 9 eye and 3 throat swab samples, 7 nasopharyngeal aspirate samples, 1 bronchoalveolar lavage sample, 3 cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples, 1 serum sample, 1 urine sample, and 2 vesicle materials (Table 1). The specimens were stored at −70°C until viral DNA was purified with the QIAamp Blood Mini kit.

TABLE 1.

Summary of patient data including age, sample source, and symptoms together with PCR and typing results for 40 clinical samplesa

| Positive samples no. | Patient age | Patient sample | Symptoms | One-step PCR result | Type by PCR-RE digestion analysisb | Type by RE analysis of full-length Ad DNAc | Nested PCR result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 mo | Feces | Diarrhea | Positive | 7 gen. var. | No sample left | ND |

| 2 | 22 yr | Throat swab sample | Fever, pharyngeal conjuctivitis headace | Positive | 7 gen. var. | 7b | ND |

| 3 | 22 yr | Conjunctiva | Pharyngeal conjunctivitis | Positive | 7 gen. var. | 7b | ND |

| 4 | 2.5 yr | Feces | Diarrhea | Positive | 40 | 40 | ND |

| 5 | 40 yr | Conjunctiva | Keratoconjunctivitis | Positive | 4 | 4a | ND |

| 6 | 39 yr | Eye sukb sample | Fever, pharyngeal conjunctivitis | Positive | 7 gen. var. | 7b | ND |

| 7 | 22 mo | Feces | Fever, conjunctivitis, bronchitis, otitis | Positive | 41 | 41 | ND |

| 8 | 29 yr | Conjunctiva | Conjunctivitis | Positive | 7 gen. var. | 7b | ND |

| 9 | 2.5 yr | Throat sample | Fever, exanthema, pharyngitis | Positive | 7 gen. var. | 7b | ND |

| 10 | 15 mo | CSF | Fever, stiff neck, photophobia | Positive | 31 | 31 | ND |

| 11 | 2.5 yr | Feces | Fever, exanthema | Positive | 7 gen. var. | 7b | ND |

| 12 | 13 mo | Feces | Diarrhea, vomiting | Positive | 31 | 31 | ND |

| 13 | 1 yr | NPA | Fever | Positive | 2, 5, or 6 | No sample left | ND |

| 14 | 72 yr | BAL | Pneumonia, | Positive | 2, 5, or 6 | No sample left | ND |

| 15 | 2 yr | NPA | Fever, cough | Positive | 2, 5, or 6 | No sample left | ND |

| 16 | 3 mo | Feces | Diarrhea, edema | Positive | 2, 5, or 6 | No sample left | ND |

| 17 | 22 yr | Vesicles | Stomatitis, fever | Positive | 1 | No sample left | ND |

| 18 | 20 yr | Vesicles | Genital ulcers | Positive | 2, 5, or 6 | No sample left | ND |

| 19 | 61 yr | CSF | Neuropathy | Positive | 1 | No sample left | ND |

| 20 | 3 mo | NPA | Lower respiratory infection | Positive | 2, 5, or 6 | No sample left | ND |

| 21 | 74 yr | NPA | Fever, meningitis | Positive | 2, 5, or 6 | No sample left | ND |

| 22 | 4 yr | Urine | ? | Negative | ND | No sample left | Positive |

| 23 | 38 yr | Eye swab sample | Conjunctivitis | Positive | 3 gen. var. | 3a | ND |

| 24 | 35 yr | Eye swab sample | Conjunctivitis | Negative | ND | No sample left | Positive |

| 25 | 35 yr | Throat swab sample | Pharyngitis | Positive | 7 gen. var. | 7b | ND |

| 26 | 9 yr | NPA | Fever, cough, | Negative | ND | No sample left | Positive |

| 27 | 46 yr | NPA | Fever, cough | Negative | ND | No sample left | Positive |

| 28 | 24 yr | Eye swab sample | Pharyngeal conjunctivitis | Negative | ND | No sample left | Positive |

| 29 | 19 yr | Eye swab sample | Pharyngeal conjunctivitis | Negative | ND | No sample left | Positive |

| 30 | 6 mo | NPA | Bronchitis, cough | Positive | 2, 5, or 6 | No sample left | ND |

| 31 | 61 yr | Feces | ? | Positive | 2, 5, or 6 | No sample left | ND |

| 32 | 2 yr | Feces | Gastroenteritis | Positive | 41 | 41 | ND |

| 33 | 1 yr | Feces | Gastroenteritis | Positive | 31 | 31 | ND |

| 34 | 16 mo | Feces | Gastroenteritis | Positive | 41 | 41 | ND |

| 35 | 4 mo | Feces | Diarrhea, vomiting | Positive | 40 | 40 | ND |

| 36 | 3 yr | Feces | Diarrhea | Positive | 7 gen. var. | 7b | ND |

| 37 | 44 yr | Serum | ? syndrome | Positive | 3 gen. var. | No sample left | ND |

| 38 | 36 yr | CSF | Guillain-Barré(?), pneumonitis | Positive | 2, 5, or 6 | 5 D2 | ND |

| 39 | 2.5 yr | Feces | Enteritis | Positive | 1 | No sample left | ND |

| 40 | 33 yr | Eye swab sample | ? | Positive | 3 gen. var. | 3a | ND |

Abbreviations: NPA, nasopharyngeal aspirits; BAL, broncoalveolar lavage sample; gen. var., genome variant; ND, not determined.

Typing results with the suggested enzymes in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 with the one-step PCR product as a template.

Results of traditional typing, which involves the evaluation of specific migration patterns on agarose gels of full-length Ad DNA cleaved with different REs.

PCR amplification.

The outer primer pair, hex1deg (5′-GCC SCA RTG GKC WTA CAT GCA CAT C-3′) and hex2deg (5′-CAG CAC SCC ICG RAT GTC AAA-3′), which created a 301-bp product, was used for both sequencing and diagnosis. The nested primer pair, nehex3deg (5′-GCC CGY GCM ACI GAI ACS TAC TTC-3′) and nehex4deg (5′-CCY ACR GCC AGI GTR WAI CGM RCY TTG TA-3′), produced an amplimer of 171 bp. All primer sequences are found between base pair position 21 and position 322 in the coding region of the hexon gene (3). One-step amplifications were carried out in 100-μl reaction mixtures containing 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 100 μM, each primer at a concentration of 0.5 μM, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.). A total of 30 μl of QIAgen-eluted DNA was added to each reaction mixture. The reaction tubes were placed in an MJ Research PTC-200 thermal cycler and were held at 94°C for 3 min, immediately followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The final cycle had a prolonged extension time of 5 min. One-tenth of the PCR mixture was subjected to nested PCR in an identical mixture but with nested primers. After amplification was completed, 10 μl of the single or the nested PCR product was electrophoresed in 2% NuSieve GTG plus 1% SeaKem ME agarose (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) at 10 V/cm for 90 min. The bands were visualized by staining with 0.25 μg of ethidium bromide per ml and inspection under UV light.

RE analysis. (i) Amplified products.

Aliquots of 5 to 15 μl of the one-step PCR mixture containing approximately 1 μg of the amplimer were digested for 2 to 3 h with 5 U of different endonucleases under conditions specified by the manufacturers (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass., and Promega Corporation). Enzyme digests were analyzed on 2% NuSieve GTG plus 1% SeaKem ME agarose gels (FMC Bioproducts) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) at 6 V/cm for 2 to 3 h.

(ii) Genomic adenovirus DNA.

A total of 2 μg of full-length genomic DNA from each viral DNA preparation was used for specific Ad typing. The DNA was digested with 10 U of the restriction enzymes BamHI, SmaI, and EcoRI or BglII for 4 to 5 h and electrophoresed in 1% SeaKem ME agarose at 2 V/cm for 16 h.

Sequencing of PCR products.

The one-step PCR products of unsequenced Ad types 1, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 18, 19, 19a, 21, 31, 34, 35, 37, and 44, together with previously sequenced Ad types 3, 4, 7, 12, 40, and 41, were separately ligated into the pT7 Blue T-vector (Novagene) and transformed to Novablue competent cells. Plasmids from positive recombinants were purified by the QIAgen midi purification protocol. The Pharmacia AutoRead Sequencing kit was used for the sequencing reactions, together with 5′ fluorescein-labeled primers (T7 promoter and U19 reverse primers). The sequencing reactions were loaded on a 6% 7 M urea acrylamide gel on a Pharmacia Automated Laser Fluorescent DNA sequencer. The MegAlign program of DNAStar (DNAStar Inc., Madison, Wis.) was used for sequence alignment and to infer phylogenesis.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the new sequences reported from this article are as follows: AF161559 for Ad1, AF161560 for Ad6, AF161561 for Ad8, AF161562 for Ad9, AF161563 for Ad10, AF161564 for Ad13, AF161565 for Ad19, AF161566 for Ad19a, AF161567 for Ad37, AF161568 for Ad44, AF161569 for Ad4, AF161570 for Ad11, AF161571 for Ad14, AF161572 for Ad21, AF161573 for Ad34, AF161574 for Ad35, AF161575 for Ad18, and AF161576 for Ad31.

RESULTS

Primers.

New degenerate primers were designed by modifying already described oligonucleotides (5, 6) corresponding to a conserved region within the hexon gene. By comparing sequence data from previously published sequences with newly published sequences of Ad3, Ad7, and Ad16 of subgenus B (36), together with Ad12 (43) and Ad48 (11) of subgenus A and subgenus D, respectively, the new outer primers (primers hex1deg and hex2deg) were designed. Degenerate base positions were introduced into the primer sequences to allow annealing to all 51 known prototypes including the new serotypes Ad50 and Ad51, together with 44 different genome types (data not shown). The modification was done to increase the homology to the hexon nucleotide sequences of Ad subgenus B members. The hexon primers used earlier (5) have been shown to require a lower annealing temperature for subgenus B compared to the temperatures required for the other subgenera, allowing amplification of this particular subgenus; this is mostly due to mismatches at the 3′ ends (9, 14, 31, 32). The nested degenerate primers were designed by comparing sequence data from this work with the newly published sequence data for Ad types 3, 7, 12, 16, and 48. These primers, nehex3deg and nehex4deg, were used in this study for confirmation of the Ad types in six clinical specimens that were not positive by a one-step PCR but that created a fragment of 171 bp.

Sequencing results.

The new degenerate hexon primers, hex1deg and hex2deg, were used to amplify DNAs of several Ad prototype strains for sequencing purposes. The one-step PCR products of Ad types 12, 18, and 31 (subgenus A), Ad types 3, 7, 11, 14, 21, 34, and 35 (subgenus B), Ad1 and Ad6 (subgenus C), Ad types 8, 9, 10, 13, 19, 19a, 37, and 44 (subgenus D), Ad4 (subgenus E), and Ad40 and Ad41 (subgenus F) were selected. The length of the amplimer produced was 301 bp for each of the 23 different types sequenced. Our sequencing results for Ad types 3, 7, 12, 40, and 41 were identical to those for the same prototype strains published previously, which led us to not publish the data. However, the sequencing result for Ad4p presented here is not in concordance with the recently published sequence of the same strain, Ad4 prototype strain RI-67, ATCC (Pring-Åkerblom et al., 1995, EMBL database accession number X84646). (i) The sequence of Pring-Åkerblom et al. has a G at position 99 in the hexon open reading frame (ORF), whereas our sequence has a C, which introduces a SmaI site in the former sequence. However, SmaI could not digest either the DNA of the Ad4 prototype strain (ATCC) or the DNA from six genome variants of Ad4. (ii) A transposition of two nucleotides, nucleotides 194 and 195, in the hexon ORF is also noted when the sequence of Pring-Åkerblom et al. (GC) is compared with ours (CG). Nucleotides G and C at that position would contribute to a BlpI site, which cannot be demonstrated in a digestion experiment with this enzyme either in the prototype strain or in the six different genome variants. On the basis of these results we suggest a second version of the Ad4 prototype hexon ORF sequence at nucleotides 46 to 299 (GenBank accession number AF161569).

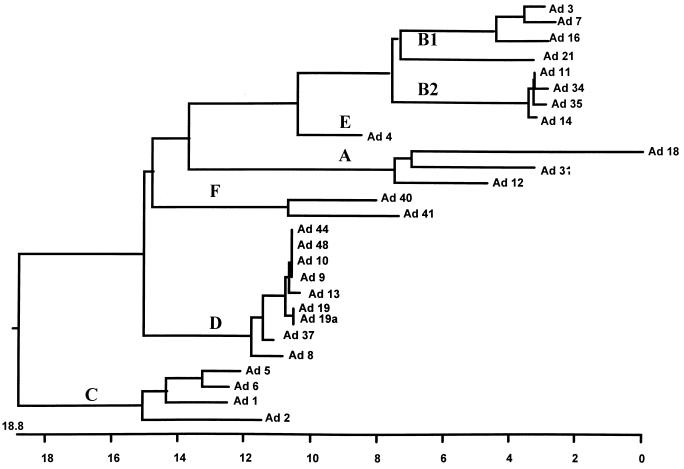

Although the amplified products originated from a conserved part of the hexon-coding gene, the sequencing data for the 26 prototype strains and genome type 19a were heterogeneous enough to allow discrimination between subgenera and even between different serotypes (Fig. 1). Bailey and Mautner (8) have previously described trees that represent other Ad gene sequences and that also show a branching pattern of the serotypes that is in good correlation with the classification into the six subgenera (subgenera A to F).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of 27 different Ad types showing the subgenus relationship between the 253-bp sequence at positions 46 to 299 within the hexon gene. The view is unbalanced, and the scale beneath the tree measures the distance between sequences. Published sequences from the GenBank database of Ad2 (J01917), Ad3 (X76549), Ad5 (X02997), Ad7 (X76551), Ad12 (X73487), Ad16 (X74662), Ad40 (X51782), Ad41 (X51783), and Ad48 (U20821) are also included.

RE analysis.

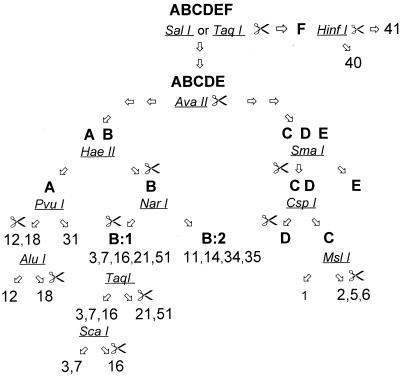

The sequencing data were further analyzed for the presence of distinctive RE cleavage sites to discriminate between Ad subgenera and, if possible, between different types (GCG Map program, version 9.1). The selection of enzymes was based on their cleavage or noncleavage of the 301-bp PCR product (i.e., 253 bp with the primer sequences subtracted), a strategy that offers a simple and user-friendly detection system. When alternatives were present, the cost of the enzymes and their availability on the market were taken into consideration to direct the choice. Conceivable enzymes were tested with the 301-bp amplimer of all 51 Ad prototype strains together with the amplimers of 44 different genome variants of the virus to create a flowchart that was as simple as possible but that still discriminated the types. A compilation of all the digestions then resulted in a scheme of the most suitable REs to be used (Fig. 2). Hence, cleavage by SalI and/or TaqI means that the amplified product originates from subgenus F and that further typing can be done by the use of HinfI to discriminate between Ad40 and Ad41. If the product is not cleaved by SalI or TaqI, the second RE to be used is AvaII, which determines what branch is to be followed next; the left branch, representing subgenera A and B, or the right branch, representing subgenera C, D, and E. Consequently, noncleavage by AvaII leads to the left branch, with HaeII being a third choice of RE. HaeII discriminates subgenus A from subgenus B. Complete distinction of subgenus A serotypes can further be done by digestion with PvuI and AluI. Subgenus B can be divided into two clusters, clusters B:1 and B:2, with NarI. Cluster B:2 represents a dead-end and virus cannot be further typed with this system, whereas cluster B:1 can be completely typed apart from difficulties in discriminating Ad21 from new type Ad51. By digestion with TaqI, Ad21 and Ad51 can be separated from Ad3, Ad7, and Ad16. Furthermore, Ad16 can be identified by ScaI cleavage. The final distinction between Ad3 and Ad7 must be done by following a second flowchart (Fig. 3). This scheme is somewhat complicated since amplimers of the prototypes (3p and 7p) respond differently to digestion compared to the responses of the genome types of these two types. Cleavage instructions are presented in Fig. 3.

FIG. 2.

Flowchart of REs for typing of PCR products framed by the general hexon primers hex1deg and hex2deg. The symbol of a pair of scissors indicates that the product will be cleaved by the enzyme in question, whereas no symbol indicates an uncleaved product. See Results for further information on the use of the flowchart.

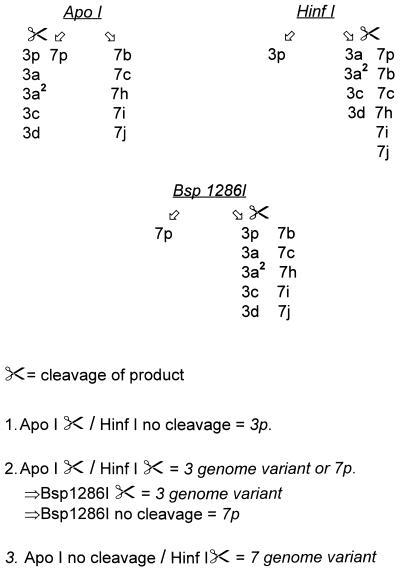

FIG. 3.

Flowchart of REs used for partial typing of prototypes and genome types of Ad3 and Ad7, subgenus B1. The symbol of a pair of scissors indicates that the product will be cleaved by the enzyme in question, whereas no symbol indicates an uncleaved product.

By following the right branch in Fig 2, noncleavage of the amplimer by SmaI can distinguish subgenus E from subgenera C and D. CspI can discriminate between subgenera C and D, and subgenus C can finally be partially typed with MslI. Subgenus D leads to a second dead-end since the similarity in the amplimer sequences makes it impossible to further type this subgenus with the REs available today.

It is very important to use the RE within the flowcharts by following the correct direction from the top to the bottom, as recommended in the text. Several enzymes have their recognition sites in the sequences of more than one subgenus or type, and when introduced too early, the results will be misleading. For example, the RE SmaI that is used in the flowchart to discriminate subgenera C and D from subgenus E will also digest subgenus F members and Ad18 of subgenus A.

Products representing Ad31 will pass the flowchart without being cleaved by any enzyme. To confirm that no inhibitors will prevent cleavage of the DNA, HinfI can be used as a DNA quality control. This RE will cut Ad31, and furthermore, it is inexpensive and is already present within the flowchart.

The RE SalI digests all genome variants of subgenus F tested so far except genome type D9 of Ad40. TaqI can discriminate all known genome types of subgenus F but also cleaves Ad21 and Ad51. However, the TaqI restriction profiles of Ad21 and Ad51 are clearly different from that of the subgenus F Ads. Ad40 and Ad41 amplimers representing all known genome types are cleaved by TaqI, yielding two fragments of 191 and 110 bp, and the Ad21 and Ad51 amplimers are cleaved, yielding two fragments of 231 and 70 bp (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of TaqI restriction profiles of amplified DNA of prototype strains of Ad types 21, 51, 40, and 41.

The digestion of the Ad16 amplimer with ScaI yields a small fragment of 41 bp, together with a larger fragment of 260 bp. The efficiency of this enzyme has, in our hands, not always been 100%, so the 260-bp product will comigrate together with the undigested 301-bp amplimer, giving twin bands on the gel. However, the interpretation of the result is still simple.

Tests with clinical samples.

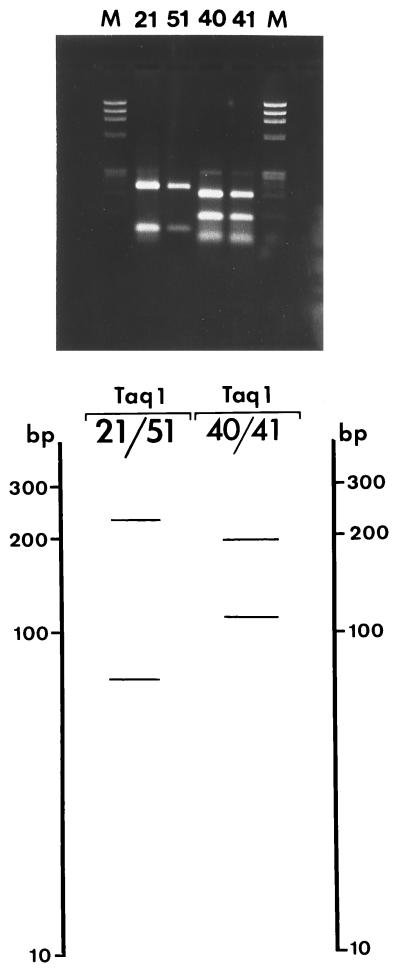

The enzymes indicated in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 were repeatedly tested (more than four times) with all 51 prototype strains and 44 genome variants (data not shown). As a final test, 40 Ad-positive samples were added to the study to estimate the use of the typing system in diagnostic work. The assay was performed directly with clinical samples, and 34 of the 40 samples were positive by a one-step PCR and could be typed by following the RE cleavage schemes. The six additional samples became positive when the general nested PCR primers were used, creating a 171-bp product too short to be used in the typing system presented here. Thirteen members of subgenus C were found, represented by 10 samples of type Ad2, Ad5, or Ad6 and 3 samples of type Ad1. Two of the subgenus C-positive samples were CSF samples from adults. The second most common subgenus found was subgenus B, represented by nine genome types of serotype Ad7, together with three genome types of serotype Ad3. The viruses in two samples with type Ad40 and three samples with type Ad41 represented subgenus F. Type Ad31 of subgenus A was found in CSF from a child and in fecal samples from two different adults. Finally, type Ad4, the only member of subgenus E, was found in the eye of a 40-year-old woman. No member of subgenus D was identified. All the results for the positive clinical samples together with patient data are summarized in Table 1. Some examples of the restriction profiles of the PCR products derived from clinical samples are given in Fig. 5.

FIG. 5.

RE digestion profiles of PCR products of viruses from six different clinical samples representing subgenera A, B1, C, E, and F. Sections: 1, Ad31, subgenus A, patient 10; 2, Ad7 variant, subgenus B1, patient 2; 3, Ad 4, subgenus E, patient 5; 4, Ad1, subgenus C, patient 39; 5, Ad40, subgenus F, patient 4; 6, Ad41, subgenus F, patient 34. See Table 1 for patient data. φX174 DNA digested with HaeIII was used as a molecular size marker. The symbol of a pair of scissors indicates that the product will be cleaved by the enzyme in question.

Traditional RE typing of Ad genomic DNA.

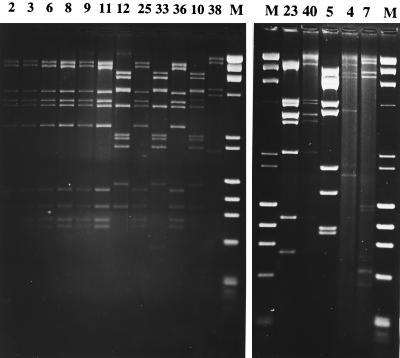

To confirm the results of typing by PCR-RE digestion, traditional RE typing was performed with full-length genomic viral DNA. The confirmation was limited because of restricted amounts of material, and therefore, only 20 of the original samples positive by a one-step PCR could be included. The specimens were inoculated onto cells, and all of them displayed a cytopathic effect characteristic of Ad infection. Ad-specific DNA was prepared from the positive cultures, and a type-specific migration pattern was obtained by BamHI digestion (Fig. 6). These results were further confirmed by digestion with SmaI, EcoRI, or BglII (data not shown). All the results obtained were in concordance with the PCR-RE typing results and also introduced more specific information about genome variants such as 3a, 4a, 5D2, and 7b (Table 1).

FIG. 6.

BamHI restriction patterns of full-length Ad DNAs extracted from cells infected with viruses from different patient samples. The numbers above each lane indicate the patient number listed in Table 1. Patients 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 11, 25, and 36 were infected with Ad7b. Patients 10, 12, and 33 were infected with Ad31, patient 38 was infected with Ad5 D2, patients 23 and 40 were infected with Ad3a, patient 5 was infected with Ad4a, and finally, patients 4 and 7 were infected with Ad40 and Ad41, respectively. Molecular size standards consisted of bacteriophage λ DNA digested with HindIII and φX174 DNA digested with HaeIII.

DISCUSSION

In 1 day the identification of Ad isolates for epidemiological surveillance can be done by using the PCR-RE digestion method. The identification is generally based on genomic typing by DNA analysis with REs or neutralization tests, which both involve cell cultivation, which consumes about 2 weeks of time. A typing method based on PCR offers a great possibility to identify fastidious Ads or Ads in specimens toxic to cell cultivation, since modern DNA extraction techniques adapted to all kinds of human tissue and fluids are available today. If necessary, this PCR-RE digestion method can be combined with more laborious systems to extend the typing capacity to include subgenus B2 and subgenus D (35, 37, 39, 44).

The Ad types within a subgenus are similar in their tropisms pathogenic potentials, tendencies to cause a latent infection, and levels of occurrence or reactivation in immunosuppressed individuals. Therefore, in the clinical setting, identification of Ads by determination of subgenus alone is often but not always sufficient when a more virulent strain must be excluded. A system of subgenus typing by PCR with the VA RNA gene regions as a target has been described; the system can be used with further differentiation with REs to confirm the subgenus identity (24). A multiplex PCR for subgenus-specific detection with selective primers from the loop l4 gene region of the hexon has also been published (38). However, in these two systems, together with other PCR typing systems (39, 45), discrimination between the different types is performed by comparing the migration of small fragments of similar sizes in a gel, a result that can ocassionally be very difficult to interpret, despite the use of high-resolution gels or high-quality molecular size markers. The PCR-RE digestion method described here provides an intelligible flowchart with a simple and clear-cut final readout, namely, cleavage or noncleavage of a PCR amplimer.

This typing system is based on cleavage of one-step PCR products. Occasionally, a one-step reaction is not sufficient to allow detection of virus DNA. To avoid the risk of false-negative results, a nested system can be used. The general pair of nested primers described herein will produce an internal product of 171 bp that can perhaps be used for partial typing since several REs have their cleavage recognition sites located in the central part of the sequences. However, a flowchart based entirely on RE cleavage of this short fragment would be too incomplete to be practicable. Instead, cell culture can be performed prior to PCR amplification if the virus concentration in a sample is too low. However, both nested PCR and combined cell culture-PCR are powerful tools and can easily detect persistent Ad infections in stool samples. The Ad that is found in a sample should therefore not always be considered the cause of illness since infections caused by members of subgenus C and serotype Ad3 are characterized by a prolonged intermittent excretion in stool (19).

The modified primers used here are highly degenerate. The primers were tested for homology to all available sequences in the GenBank database, with no indication of unspecific binding. Furthermore, the two sets of primers, including the ones used for nested PCR, have been used in routine diagnostic work for 5 years without the introduction of unspecific amplifications. The viruses in a limited number of clinical samples were typed with the PCR-RE digestion system to evaluate the method. The comparison with full-length DNA-RE typing in this study indicated that the PCR-RE digestion method is reliable and can be used as a tool for characterization of Ads in samples in daily routine diagnostic work. Furthermore, in our study the distribution of genotypes into each subgenus was similar to the distributions found in an extensive epidemiological study of 200 Ad isolates from the Stockholm area of Sweden from 1987 to 1992 (21). All 200 Stockholm isolates were typed by using RE analysis of full-length Ad DNA. Nine percent of the 34 samples contained Ads of subgenus A in our study, whereas 8% of the samples in the Stockholm study contained Ads of subgenus A. The only member that we found was type 31, which also was predominant in Stockholm. Subgenus B Ads were responsible for 35% of the Ad infections found in Umeå, whereas they were responsible for 25.5% of the Ad infections in Stockholm. The higher figure was probably due to an outbreak of type 7b during this short 6-month period of sampling. The distribution of members of subgenus C was very similar in both studies: 38% in Umeå, and 34% in Stockholm. No representative of subgenus D was found in Umeå, whereas 22.5% of the infections in Stockholm were caused by subgenus D, dominated by one nosocomial outbreak of keratoconjunctivitis due to adenovirus 19a. Ads of subgenus E were found in 3% of the typed samples in both areas, whereas Ads of subgenus F caused symptoms in 15% of the patients in our study and 7% of the patients in the Stockholm study.

The importance of Ads as a cause of disseminated disease has remained underappreciated, perhaps since Ad infections have been diagnosed primarily through the use of cell culture. The fact that cell culture is sometimes insensitive for the detection of this virus has hindered recognition of the role that Ads may play in morbidity and mortality in patients with symptoms not normally associated with this virus (9, 15, 16, 18, 25, 41).

When designing primers it is important to introduce sequences derived not only from prototype strains since prototype strains and genome types of the same serotype do not exhibit identical sequences and the prototype strains are presumed to circulate more rarely in the population. In spite of this fact, we cannot exclude the possibility that there exist in nature other Ad strains whose hexon regions do not have the same restriction properties as those seen in the present study. However, this method can facilitate typing of human Ads in a variety of different sample materials and thereby also contribute to an increased understanding of the pathological importance of these viruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. C. deJong, A. Kajon, A. Kidd, Q. G. Li, D. Schnurr, and R. Wigand for the Ad strains used in the study. We also thank P. Juto for access to clinical samples and J. Forssell for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian T, Sassinek J, Wigand R. Genome type analysis of 480 isolates of adenovirus types 1, 2, and 5. Arch Virol. 1990;112:235–248. doi: 10.1007/BF01323168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adrian T H, Wadell G, Hierholzer J C, Wigand R. DNA restriction analysis of adenovirus prototypes 1 to 41. Arch Virol. 1986;91:277–290. doi: 10.1007/BF01314287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akusjärvi G, Aleström P, Pettersson M, Lager M, Jörnvall H, Pettersson U. The gene for the adenovirus 2 hexon polypeptide. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:13976–13979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allard A, Wadell G, Evander K M, Lindman G K K. Specific properties of two enteric adenovirus 41 clones mapped within early region 1A. J Virol. 1985;54:145–150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.54.1.145-150.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allard A, Girones R, Juto P, Wadell G. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of adenoviruses in stool samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2659–2667. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2659-2667.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allard A, Albinsson B, Wadell G. Detection of adenoviruses in stools from healthy persons and patients with diarrhea by two-step polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol. 1992;37:149–157. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890370214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allard A, Kajon A, Wadell G. Simple procedure for discrimination and typing of enteric adenoviruses after detection by polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol. 1994;44:250–257. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890440307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey A, Mautner V. Phylogenetic relationships among adenovirus serotypes. Virology. 1994;205:438–452. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardosa M J, Krishnan S, Hooi Tio P, Perera D, Chang Wong S. Isolation of subgenus B adenovirus during a fatal outbreak of enterovirus 71-associated hand, foot, and mouth disease in Sibu, Sarawak. Lancet. 1999;354:987–991. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper R J, Yeo C Y, Bailey A S, Tullo A B. Adenovirus polymerase chain reaction assay for rapid diagnosis of conjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford-Miksza L, Schnurr D P. Analysis of 15 hexon proteins reveals the location and structure of seven hypervariable regions containing serotype-specific residues. J Virol. 1996;70:1836–1844. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1836-1844.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Jong J C, Wigand R, Kidd A H, Wadell G, Kapsenberg J G, Muzerie C J, Wermenbol A G, Firtzlaff R-G. Candidate adenoviruses 40 and 41: fastidious adenoviruses from human infant stool. J Med Virol. 1983;11:215–231. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890110305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Jong J C, Wermenbol A G, Verweij-Uijterwaal M W, Slaterus K W, Wertheim-van Dillen P, van Doornum G J J, Khoo S H, Hierholzer J C. Adenoviruses from AIDS patients, including two new candidate serotypes: Ad50 and Ad51 of subgenus D and B1, respectively. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3940–3945. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3940-3945.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Echavarria M, Forman M, Ticehurst J, Dumler J S, Charache P. PCR method for detection of adenovirus in urine of healthy and human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3323–3326. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3323-3326.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Echavarria M S, Ray S C, Ambinder R, Dumler J S, Charache P. PCR detection of adenovirus in a bone marrow transplant recipient: hemorrhagic cystitis as a presenting manifestation of disseminated disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:686–689. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.686-689.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flomenberg F, Gutierrez E, Piakowski V, Casper J T. Detection of adenovirus DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells by polymerase chain reaction assay. J Med Virol. 1997;51:182–188. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199703)51:3<182::aid-jmv7>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fong C K Y. Adenoviridae. In: Hsiungs C D, editor. Diagnostic virology. 4th ed. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press; 1994. pp. 232–235. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forsnes E V, Eggleston M K, Wax J R. Differential transmission of adenovirus in a twin pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:817–818. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox J P, Hall C E, Cooney M K. The Seattle Virus Watch. VII. Observations of adenovirus infections. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105:362–386. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hierholzer J C. Adenoviruses in the immunocompomised host. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:262–274. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.3.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson M E, Andersson M A, Thörner P. Adenoviruses isolated in the Stockholm area during 1987–1992: restriction endonuclease analysis and molecular epidemiology. Arch Virol. 1994;137:101–115. doi: 10.1007/BF01311176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kajon A, Wadell G. Genome analysis of South American adenovirus strains of serotype 7 collected over a 7-year period. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2321–2323. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2321-2323.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kajon A E, Mistchenko A S, Videla C, Hortel M, Wadell G, Avendaño L F. Molecular epidemiology of adenovirus acute lower respiratory infections of children in the south cone of South America (1991–1994) J Med Virol. 1996;48:151–156. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199602)48:2<151::AID-JMV6>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kidd A H, Jönsson M, Garwicz D, Kajon A, Wermenbol A G, Verweij M W, de Jong J C. Rapid subgenus identification of human adenovirus isolates by a general PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:622–627. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.622-627.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuwano K, Kawasaki M, Kunitake R, Hagimoto N, Nomoto Y, Matsuba T, Nakanishi Y, Hara N. Detection of group C adenovirus DNA in small-cell lung cancer with the nested polymerase chain reaction. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1997;123:377–382. doi: 10.1007/BF01240120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, Wadell G. The degree of genetic variability among adenovirus type 4 strains isolated from man and chimpanzee. Arch Virol. 1988;101:65–77. doi: 10.1007/BF01314652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q G, Hambraeus J, Wadell G. Genetic relationship between thirteen genome types of adenovius 11, 34, and 35 with different tropism's. Intervirology. 1991;32:338–350. doi: 10.1159/000150218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Zheng G, Liu Y, Wadell G. Molecular epidemiology of adenovirus types 3 and 7 isolated from children with pneumonia in Beijing. J Med Virol. 1996;49:170–177. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199607)49:3<170::AID-JMV3>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Q G, Henningsson A, Juto P, Elgh F, Wadell G. Use of restriction fragment analysis and sequencing of a serotype-specific region to type adenovirus isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:844–847. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.844-847.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mistchenko A S, Robaldo J F, Rosman F C, Koch E R R, Kajon A. Fatal adenovirus infection associated with new genome type. J Med Virol. 1998;54:233–236. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199803)54:3<233::aid-jmv15>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris D J, Bailey A S, Cooper R J, Turner P C, Jackson R, Corbitt G, Tullo A B. Polymerase chain reaction for rapid detection of ocular adenovirus infection. J Med Virol. 1995;46:126–132. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890460208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris D J, Cooper R J, Barr T, Bailey A S. Polymerase chain reaction for rapid diagnosis of respiratory adenovirus infection. J Infect. 1996;32:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(96)91250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy F A, Fauquet C M, Bishop D H L, Ghabrial S A, Jarvis A W, Martelli G P, Mayo M A, Summers M D, editors. Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Sixth report. Vienna, Austria: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pauschinger M, Bowles N E, Fuentes-Garcia F J, Pham V, Kuhl U, Schwimmbeck P L, Schultheiss HP, Towbin J A. Detection of adenoviral genome in the myocardium of adult patients with idiopathic left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 1999;10:1348–1354. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.10.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pring-Åkerblom P, Adrian T. Type- and group-specific polymerase chain reaction for adenovirus detection. Res Virol. 1994;145:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(07)80004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pring-Åkerblom P, Trussenaar F E J, Adrian T. Sequence characterization and comparison of human adenovirus subgenus B and E hexons. Virology. 1995;212:232–236. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pring-Åkerblom P, Adrian T, Köstler T. PCR-based detection and typing of human adenovirus in clinical samples. Res Virol. 1997;148:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(97)83992-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pring-Åkerblom P, Trijssenaar F E J, Adrian T, Hoyer H. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction for subgenus-specific detection of human adenoviruses in clinical samples. J Med Virol. 1999;58:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saitoh-Inagawa W, Oshima A, Aoki K, Itoh N, Isobe K, Uchio E, Ohno S, Nakajima H, Hata K, Ishiko H. Rapid diagnosis of adenoviral conjunctivitis by PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2113–2116. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2113-2116.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnurr D, Dondero M. Two new candidate adenovirus serotypes. Intervirology. 1993;36:79–83. doi: 10.1159/000150325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schnurr D, Bollen A, Crawford-Miksza L, Dondero M E, Yagi S. Adenovirus mixture isolated from the brain of an AIDS patient with encephalitis. J Med Virol. 1995;47:168–171. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shinagawa M, Matsuda A, Ishiyama T, Goto H, Sato G. A rapid and simple method for preparation of adenovirus DNA from infected cells. Microbiol Immunol. 1983;27:817–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1983.tb00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sprengel J, Schmitz B, Heuss-Neitzel D, Zock C, Doerfler W. Nucleotide sequence of human adenovirus type 12 DNA: comparative functional analysis. J Virol. 1994;68:379–389. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.379-389.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeuchi S, Itoh N, Uchio E, Aoki K, Ohno S. Serotyping of adenoviruses on conjunctival scrapings by PCR and sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1839–1845. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1839-1845.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tiemessen C T, Nel M J. Detection and typing of subgroup F adenovirus using the polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods. 1996;59:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(96)02015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Avoort H G A M, Wermenbol A G, Zomerdijk T P L, Kleijne J A F W, van Asten J A A M, Jensma P, Osterhaus A D M E, Kidd A H, de Jong J C. Characterization of fastidious adenovirus types 40 and 41 by DNA restriction enzyme analysis by neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Virus Res. 1989;12:139–158. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(89)90060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wadell G, Hammarskjöld M-L, Winberg G, Varsanyi T M, Sundell G. Genetic variability of adenoviruses. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1980;354:16–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb27955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wadell G, de Jong J C. Restriction endonucleases in identification of a genome type of adenovirus 19 associated with keratoconjunctivitis. Infect Immun. 1980;27:292–296. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.2.292-296.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wadell G, Allard A, Evander M, Li Q. Genetic variability and evolution of adenoviruses. Chem Scripta. 1986;26B:325–335. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wadell G, Allard A, Hierholzer J C. Adenoviruses. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F, Yolken R N, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 970–982. [Google Scholar]