Abstract

Background

Acne affects more than 80% of adolescents and young adults, who most often develop acne scars. Supporting data on the effect of acne scars on patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQOL) are limited.

Objective

The aim was to determine how the severity of acne scars impacts the HRQOL of afflicted individuals.

Methods

In this population-based cross-sectional study, 723 adults with facial acne scars but without active acne lesions self-completed the Self-assessment of Clinical Acne-Related Scars (SCARS) questionnaire formulated to investigate degree of acne scarring. The Facial Acne Scar Quality of Life (FASQoL), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and Dysmorphic Concern Questionnaire (DCQ) were completed to assess the attitude of these patients toward their scars and the impact of scarring on their HRQOL.

Results

The mean (standard error) DLQI score for facial acne scars was 6.26 (0.22). Acne scars were considered a ‘very large’ or ‘extremely large’ concern by 19.3% of participants with mild scars as compared to 20.1% and 34.0% of participants with moderate and severe/very severe scars, respectively (P = 0.003). Higher FASQoL scores were associated with increased severity of scarring (P = 0.001). In total, 16.9% of participants had clinical features of dysmorphia (i.e., DCQ > 13). DCQ scores were significantly higher among participants with more severe scarring (mean DCQ score of 8.04 [0.28], 8.40 [0.18], and 10.13 [0.08] among participants with mild, moderate, and severe/very severe acne scars, respectively; P = 0.001). Most commonly reported signs of emotional distress were self-consciousness (68.0%) and worry about scars not going away (74.8%).

Conclusions

This study highlights the significant psychosocial impact of atrophic acne scars in the form of embarrassment and self-consciousness. Individuals with mild scars also expressed significant impact on quality of life that increased with aggravation of scar severity. Patient-reported outcomes provide an insight into the physical, functional, and psychological impact of acne scarring from the patient’s perspective.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40257-021-00628-1.

Key Points

| Atrophic acne scarring had significant psychosocial impact in the form of embarrassment and self-consciousness. |

| Individuals with mild scars also expressed significant impact on quality of life. |

| Patient-reported outcomes provide an insight into the physical, functional, and psychological impact of acne scarring from the patient’s perspective. |

Introduction

Acne, a common chronic inflammatory skin condition, affects more than 80% of adolescents and young adults [1, 2] and ranks among the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide [3, 4]. Scarring can be a major concern for patients with acne, as scars can persist [2], and are often experienced by the majority of acne-afflicted individuals [5–8].

Despite the scarcity of data, acne scarring is thought to be associated with adverse psychosocial disability resulting from embarrassment, self-consciousness, and poor self-esteem. People who develop acne scars often exhibit symptoms of frustration, depression, anxiety, and stress [9], and fear that their appearance may interfere with their academic performance, professional relationships, and chances of future employment [9]. A few attempts have been directed to explore the specific psychological effects of acne scar, a condition separate from acne. Most published reports concerning the impact of acne scars on patient wellbeing are limited to the use of tools that lack the sensitivity and specificity to assess the impact of scars [10]. In addition, these studies report scars according to clinical judgment despite the discrepancy between patient perception of scar severity and dermatologist assessment [5, 7, 11]. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), including symptom severity and impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL), are key components of effective, patient-centered services aimed at capturing and meaningfully incorporating patient experiences, perspectives, needs, and priorities into clinical practice and drug development [12].

In this population-based survey of adults with facial acne scarring but with no evidence of active acne, we aimed to determine the impact of facial acne scars on HRQOL from the patients’ perspective, using recently developed patient self-completion instruments that specifically address acne scarring evaluation.

Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional web-based survey conducted between November 2019 and January 2020 involved a panel of participants that agreed to respond to online health surveys about their medical condition(s). The research complied with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and all international/local data protection legislation and Insights Association/European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR)/European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA). All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. The survey was administered in six countries (the USA, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, and Brazil) in their native languages. A quota sampling method based on geographical location was used to ensure that sampled participants were representative of the acne scar population in these countries. A weighting adjustment method was applied at the country level where deviations were observed between the survey sample structure and the expected age and sex distribution of the acne scar population [13]. Country weights were also used to account for population size (see the electronic supplementary material, Supplementary text 1). Here we report on the weighted data. Based on the formula (click through/panelists who received an email with the study link), the response rate of the survey was approximately 5%.

After providing informed consent, all potential participants completed the sociodemographic questions and were screened for survey eligibility. Eligible participants were male and female patients between 18 and 55 years (inclusive) of age. At screening, participants were required to have mild to very severe atrophic acne scars on their faces as well as a history of previous mild to very severe acne. Participants’ acne was to be clear (no active lesions) or almost clear (e.g., a few scattered blackheads or whiteheads [open or closed comedones] and very few acne bumps [papules]) during the 2 years prior to the survey. Thirteen participants (1.8%) who could not recall the exact date of the previous acne episode were included in the survey. The presence and severity of acne was self-reported. Participants were requested to grade the severity of their facial acne on a scale from 0 to 5 using a six-category global system of acne classification based on the self-rated global assessment [14]. To help self-assessment of acne severity, photo scales were provided as examples of severity alongside text descriptions. The Self-assessment of Clinical Acne-Related Scars (SCARS) questionnaire was used to rate the severity of facial atrophic acne scars [15]. Photographs of the different types of post-acne scars were shown to patients to help them recognize atrophic scars. The SCARS questionnaire comprises five questions, each with five possible answers to be scored from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater acne scar severity. The clinical interpretation of SCARS scores is as follows: 0–2, clear/almost clear scarring; 3–6, mild scarring; 7–10, moderate scarring; 11–20, severe/very severe scarring. The questionnaire captured demographic information (e.g., sex, age, and residential background) and clinical characteristics of acne and scarring (e.g., age at the onset of acne and acne scars, age at the time of initial management of acne and acne scars, age at the time of initial treatment for acne and acne scars by a medical institution, time period without acne, family history of acne scars, self-assessed severity of acne and acne scars). The questions dealing with perceptions of acne scars were mainly formulated for validated HRQOL scales, including the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI™) [16] and the Facial Acne Scar Quality of Life (FASQoL™) [15] referenced to the preceding week. The Dysmorphic Concern Questionnaire (DCQ™) [17] was also included to measure cognitive and behavioral symptoms of overconcern with physical appearance due to acne scars, with no time frame per developer instructions. Conditions concerning the questionnaire’s translation and use were fulfilled per the developer’s requests. A series of individual questions regarding psychosocial variables (e.g., stress, anxiety, or depression self-report; feeling of embarrassment; fear of being photographed; and stigma) and coping behaviors (e.g., avoidance of participation in public activities and concealing of acne scars) were also included. Questions for the survey were generated based on insights from previous in-depth qualitative interviews of patients with acne scars residing in study countries [18] and further validated by clinical experts (JT and BD). Linguistic translation was conducted in accordance with the conventional methodology (TransPerfect, October 2019).

In addition to the survey content, clinical experts (JT and BD) also contributed to the development of the acne screening criteria and selection of PRO measures.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the survey (weighted) data set. For continuous variables, mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) were calculated. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies. This report presents the results for all countries together. Additional analyses are ongoing, and their results will be reported in upcoming publications.

The DLQI and questionnaires were scored as per their respective guidelines. The DLQI comprised ten questions, each with four possible answers and scores from 0 to 3. The overall response scores were 0–30, with higher scores indicating greater impairment in HRQOL. The clinical interpretation of DLQI scores was as follows: 0–1, no effect at all on the patient’s life; 2–5, a small effect on the patient’s life; 6–10, a moderate effect on the patient’s life; 11–20, a very large effect on the patient’s life; 21–30, an extremely large effect on the patient’s life [16]. The FASQoL comprised ten questions, each with five possible answers and scores from 0 to 4. The total score range was 0–40, with higher scores reflective of greater HRQOL impairment. The DCQ comprised seven questions, and each had four possible answers with a maximum of 3 points and total maximum and minimum scores of 21 and 0, respectively; the cut-off was 14 for ‘clinical’ dysmorphic concern and 11–13 for ‘sub-clinical’ dysmorphic concern [17].

The continuous variables were analyzed using the Student’s t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) if one of the variables being compared had two or more levels (e.g., age groups). Dependency between the chosen variables was determined using the Pearson’s correlation test. The Spearman correlation analysis was performed to investigate the relationships between ordinal and interval level variables. Categorical variables were analyzed by the chi-squared independence test with Yates correction and by Fisher’s exact test. All tests were two-tailed, and a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Multivariate Regression

Multivariate models were built to adjust for variables identified in the literature as likely to be independently associated risk factors for acne scars or those that impacted the HRQOL (i.e., age, sex, urban versus rural residential background and country of residence, acne scar severity grade, type of skin, education, and employment status). Country was modeled as the primary sampling unit to account for clustering of data at the country level. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were generated. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. STATA version 15 was used for analyses.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 723 patients with post-acne scars were included in this survey (see the electronic supplementary material, Supplementary Table 1, for socio-demographic data). At the time of questionnaire completion, all patients self-reported clear (16%) or almost clear (84%) acne, and had atrophic acne scars on their faces. Of all patients, 31.6%, 49.6%, and 18.8% had mild, moderate, and severe to very severe acne scars (mean severity score of 8.1 [SEM 0.09] on the SCARS scale of 0–20, 20 being the most severe) (Supplementary Table 1). The most commonly self-reported type of atrophic acne scars was ‘ice pick’ scars (reported by 599 patients; 82.8%), followed by ‘boxcar’ scars (n = 162; 22.4%) and ‘rolling’ scars (n = 53; 7.4%).

The severity of acne scars significantly increased in patients who had experienced higher facial acne severity in the past (mean scar severity score of 8.51 [0.06] in the moderate to very severe acne group vs 7.71 [0.16] in the mild acne group [P = 0.009]) as well as in those who experienced longer duration of facial acne (P value for trend = 0.006) (data not shown). No difference was observed in acne scar severity scores based on gender (P = 0.120), age group (P = 0.116), or Fitzpatrick scale (P = 0.491).

Impact of Acne Scars on HRQOL

DLQI Scale Analyses

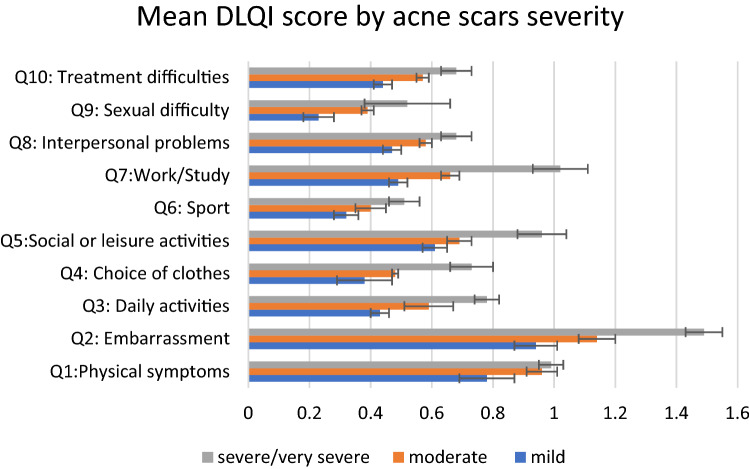

In total, 545 patients (75.4%) indicated facial scars as a concern (Table 1). Most patients were self-conscious about their scars (76%), and almost half reported scarring to have a negative impact on their social and leisure activities (48.1%) and work performance (41.7%) (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 1a, b, see the electronic supplementary material). The mean (SEM) DLQI score for facial acne scars was 6.26 (0.22). Overall, 22.5% of patients reported a DLQI score > 10 (‘very large’ or ‘extremely large’ impact). No significant differences were observed in DLQI scores across countries (P = 0.308). High DLQI scores were more frequently reported in patients with self-rated higher severity of scars. A DLQI score > 10 was reported by 19.3% of patients with mild acne scars as compared to 20.1% and 34.0% of patients with moderate and severe/very severe scars, respectively (P = 0.003).

Table 1.

Comparison of the prevalence of moderate, large, and extremely large effects of acne scars on HRQOL according to age, sex, type of skin (Fitzpatrick scale), and severity of acne scars

| DLQI score mean (SEM) | No effect score (0–1), n (%) | Mild effect score (2–5), n (%) | Moderate effect score (6–10), n (%) | Very large effect score (11–20), n (%) | Extremely large effect score (21–30), n (%) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 6.26 (0.22) | 178 (24.6) | 253 (35.0) | 129 (17.9) | 140 (19.3) | 23 (3.1) | |

| Sex | 0.135 | ||||||

| Male | 6.34 (0.19) | 98 (28) | 108 (31.0) | 62 (17.6) | 67 (19.3) | 15 (4.2) | |

| Female | 6.17 (0.31) | 80 (21.4) | 145 (38.8) | 68 (18.2) | 72 (19.4) | 8 (2.2) | |

| Age groups (years) | 0.021 | ||||||

| 18–24 | 7.19 (0.53) | 16 (17.2) | 29 (32.2) | 21 (22.6) | 24 (25.8) | 2 (2.2) | |

| 25–45 | 6.56 (0.25) | 113 (21.8) | 185 (35.7) | 97 (18.8) | 104 (20.0) | 20 (3.8) | |

| 46–55 | 4.09 (0.13) | 49 (43.7) | 39 (34.4) | 11 (10.0) | 12 (10.9) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Scar severity on face | 0.014 | ||||||

| Mild | 5.00 (0.30) | 75 (32.7) | 82 (35.7) | 28 (12.2) | 43 (18.7) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Moderate | 6.34 (0.22) | 78 (21.8) | 133 (37.0) | 76 (21.1) | 59 (16.6) | 13 (3.5) | |

| Severe or very severe | 8.12 (0.39) | 25 (18.5) | 39 (28.5) | 26 (19.0) | 37 (27.6) | 9 (6.4) | |

| Fitzpatrick scale | 0.223 | ||||||

| Type I: light, pale white | 7.85 (1.83) | 3 (9.86) | 12 (38.11) | 9 (29.1) | 5 (16.80) | 2 (6.12) | |

| Type II: white, fair | 4.98 (0.27) | 33 (32.81) | 38 (37.06) | 14 (13.86) | 16 (15.50) | 1 (1.00) | |

| Type III: medium, white to olive | 6.34 (0.27) | 48 (24.04) | 69 (34.63) | 35 (17.87) | 40 (20.16) | 7 (3.30) | |

| Type IV: olive, moderate brown | 5.53 (0.56) | 49 (26.45) | 66 (35.22) | 39 (20.91) | 28 (15.04) | 4 (2.39) | |

| Type V: brown, dark brown | 6.89 (0.66) | 35 (20.34) | 65 (38.37) | 26 (15.51) | 37 (21.65) | 7 (4.14) | |

| Type VI: black, very dark brown to black | 8.81 (0.50) | 10 (28.47) | 4 (11.43) | 5 (15.30) | 14 (39.20) | 2 (5.60) |

DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, HRQOL health-related quality of life

*P value for the comparison of HRQOL scores across each variable category (e.g., male vs female)

Fig. 1.

Mean (SEM) DLQI scores for each questionnaire item (Q1–Q10) based on acne scarring severity grades. Each question was scored from a minimum of 0 (i.e., no impact on HRQOL) to a maximum of 4 (i.e., very strong impact on HRQOL). P values for the comparison of scores across acne scarring severity groups for adjusted analyses including age, sex, residential background and country of residence, acne scar severity grade, type of skin, education, and employment status are as follows: Q1 = 0.036; Q2 = 0.001; Q3 = 0.001; Q4 = 0.051; Q5 = 0.001; Q6 = 0.087; Q7 = 0.002; Q8 = 0.017; Q9 = 0.033; Q10 = 0.020. DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, HRQOL health-related quality of life, Q DLQI questionnaire item number

The association between DLQI score and scar severity per SCARS instrument (Fig. 1) remained significant in the analyses stratified by age and sex, as well as in the multivariate models accounting for confounding factors (i.e., age, sex, employment status, education, country of residence, and Fitzpatrick scale) (Supplementary Table 2). The multivariate analysis showed that, on average, the youngest group (18–24 years old) experienced the greatest impact of acne scar on HRQOL (Supplementary Table 2; Supplementary Fig. 1a); gender difference did not always reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

FASQoL Scale Analyses

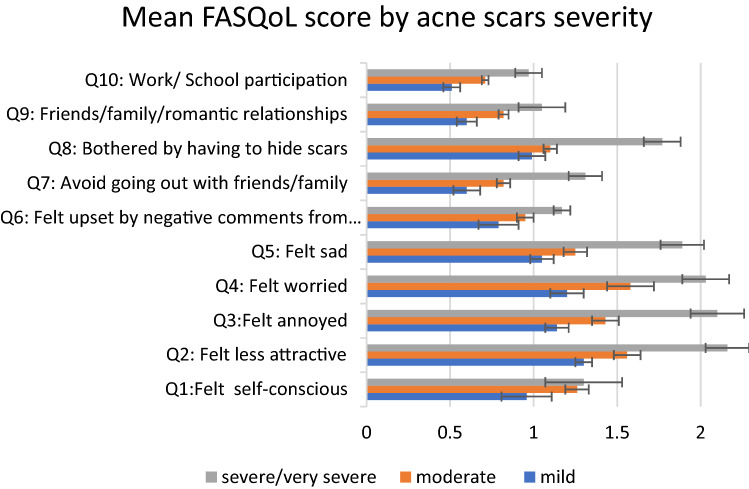

The mean FASQoL score for facial acne scars was 11.54 (SEM 0.55) on a 1–40 scale where 40 reflected the highest HRQOL impairment. The mean score was significantly different across countries, and was higher in the USA (12.48 [0.73]) and Brazil (12.08 [0.81]) than in the EU countries (8.92 [0.51]) (the USA vs EU, P = 0.0001; Brazil vs EU, P = 0.001). Overall, emotional wellbeing was the most impacted dimension of FASQoL (Fig. 2). The most frequently reported emotional distress features were feeling less attractive (77.4%), self-conscious (68.0%), annoyed (75.4%), and worried about scars not going away (74.8%). Sadness associated with acne scars affected 68.4% of participants (Fig. 2). Being bothered about having to hide scars was also a frequently reported concern in FASQoL (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean (SEM) FASQoL scores for each questionnaire item (Q1–Q10) based on acne scarring severity grades. Each question is scored from a minimum of 0 (i.e., no impact on HRQOL) to a maximum of 3 (i.e., very strong impact on HRQOL). P values for the comparison of scores across acne scarring severity groups for adjusted analyses including age, sex, residential background and country of residence, acne scar severity grade, type of skin, education, and employment status are as follows: Q1 = 0.003; Q2 = 0.001; Q3 = 0.001; Q4 = 0.001; Q5 = 0.001; Q6 = 0.001; Q7 = 0.002; Q8 = 0.001; Q9 = 0.015; Q10 = 0.003. FASQoL Facial Acne Scar Quality of Life, HRQOL health-related quality of life, Q FASQoL questionnaire item number

In the multivariate analysis, higher FASQoL scores were associated with increased severity of scarring (mean [SEM] FASQoL of 9.14 [0.54], 11.48 [0.53], and 15.73 [1.00] in patients with mild, moderate, and severe/very severe acne scars, respectively; P = 0.001). HRQOL impairment was also higher among younger participants (mean score of 13.61 [0.69], 11.90 [0.58], and 8.17 [0.36] for participants from the 18–24, 25–45, and 46–55 years age groups, respectively; P = 0.002) and female patients (mean score of 10.46 [0.53] and 12.55 [0.59] among male and female patients, respectively; P = 0.002).

Overall, there was a significant correlation between DLQI and FASQoL scores (Pearson’s r = 0.683; P < 0.001) (data not shown).

DCQ Analyses

The mean DCQ score for facial acne scarring was 8.61 (0.18) on a scale of 0–21, 21 indicating more overconcern with acne scar appearance. DCQ scores were significantly higher among participants with more severe acne scarring (mean DCQ score of 8.04 [0.28], 8.40 [0.18], and 10.13 [0.08] among patients with mild, moderate, and severe/very severe acne scars, respectively; P = 0.001) (Fig. 2). Overconcern with scar appearance was more commonly reported by female patients (7.85 [0.09] and 9.33 [0.26] in male and female patients, respectively; P = 0.0004) and younger participants (9.77 [0.34], 8.60 [0.16], and 7.72 [0.21] for 18–24, 25–45, and 46–55 years age groups, respectively; P = 0.004) (data not shown).

Overall, 16.9% of patients reported a DCQ score > 13, indicating overconcern with self-appearance of clinical significance; no significant differences were noted across countries (P = 0.604). In the multivariate analysis, the risk of clinical dysmorphic concern was significantly higher among participants with severe or very severe scars (adjusted OR 2.27, 95% CI 1.76–2.92, P = 0.001) and the youngest patients (OR 2.72, 95% CI 1.22–6.07, P = 0.023).

In comparison with the participants without dysmorphic concern, those with dysmorphic concern more often avoided activities associated with public exposure (e.g., video chatting [adjusted OR 3.82, 95% CI 2.70–5.41, P = 0.001], participation on social media [OR 3.75, 95% CI 2.15–6.57, P = 0.002], being photographed [OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.80–2.69, P = 0.001], participation in sport activities [OR 4.21, 95% CI 1.01–17.51, P = 0.049], participation in extracurricular activities [OR 3.59, 95% CI 2.48–5.20, P = 0.001], and going out with friends [OR 5.14, 95% CI 3.28–8.04, P = 0.001]). These patients were also more likely to report feeling less attractive (OR 3.08, 95% CI 1.77–5.35, P = 0.003) or embarrassed (OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.60–2.83, P = 0.001).

Overall, the DCQ score moderately correlated with DLQI (r = 0.47; P < 0.001) and FASQoL (r = 0.60; P < 0.001) scores (data not shown).

Discussion

The studies addressing the patient’s perspective on the impact of acne scars on their quality of life are sparse. In the present study, we used a self-rated acne scar severity tool and a generic HRQOL scale widely used in dermatology (DLQI) in combination with an acne scar-specific HRQOL scale (FASQoL) to determine the impact of facial acne scars on patient wellbeing without the influence of acne, as the participants were confirmed to have no acne at the time of survey completion. The DLQI-based assessment revealed a mean score of 6.26, suggesting that acne scars impair HRQOL in a manner comparable to other disabling skin conditions such as Behçet’s syndrome (DLQI 5.7), Darier’s disease (DLQI 5.89), Hailey–Hailey disease (DLQI 6.06), rosacea (DLQI 6.1), cutaneous lupus erythematosus (DLQI 6.50), and pityriasis rosea (DLQI 6.36) [19]. These results are in line with the few reports on acne scars published so far that have recorded DLQI scores of 5.61 [20] and 6.3 [21] in Asian populations.

We identified ‘acceptability to self and others’ and ‘social functioning’ as the key areas of impact on DLQI and FASQoL. Concerns with stigmatization and low self-esteem were also reported. Overall, 17% of participants showed signs of overconcern with acne scar appearance and reported coping behaviors such as hiding their scars or avoiding public exposure.

Multivariate analysis controlling for confounding factors (e.g., socio-demographics) suggested severe acne scars, young age, and female gender to be independently associated with the presentation of psychosocial distress in patients with acne scars. Higher self-rated severity of scarring was associated with increased HRQOL scores in the domains of social and emotional health. This observation is consistent with the previous findings, suggesting a significant association between perceived severity of skin conditions and poorer HRQOL [22]. Nevertheless, 19% of participants with mild acne scars showed high impairment in HRQOL, indicative of the negative effect of even mild acne scars on self-image.

Previous studies have also reported female patients to be more self-conscious and embarrassed about their skin than male counterparts [22, 23]. We could not establish statistical significance for gender differences, possibly supporting the recent views of men becoming more psychologically affected with their appearance [22] and thus reducing the previously reported gender gap [24].

A major advantage of this study is that all participants were recruited from opt-in online panels drawn from the general population, which is important to comprehensively assess the possible impact of the disease across the wide clinical and demographic variability noted in the general population [25]. By excluding patients with concurrent active acne and acne scars, we more accurately focused on the burden of acne scars alone rather than active acne or acne scars combined. The survey aimed at representing several regions and continents in the world. The overall psychological impact of acne scarring was similar across the different countries, as reflected by the DLQI and mean DCQ scores. However, some differences were observed with FASQoL. Additional data are warranted to further explore this finding. As the study comprised a population of volunteers, a non-response selection bias is possible, and the final survey sample may not completely represent the total scarred population. Our study had several limitations. The recruitment relied on self-reported severity to identify people with mild, moderate, and severe acne scars. A gap between dermatologists’ clinical definition of acne scars and people’s own perception of the disorder has been reported in the literature, and therefore, a priori, we may expect a proportion of false-negative and false-positive answers. We attempted to improve the reliability of the self-reported diagnosis by facilitating self-assessment of severity with a validated acne scars grading system tool, i.e., SCARS [15], and photographs with examples of acne and acne scars were provided to assist with self-recognition.

On the other hand, it is important to consider the patient subjective acne scars severity rating; PROs, including symptom severity, serve as a key component of effective, patient-centered services aimed at capturing and meaningfully incorporating patient experiences, perspectives, needs, and priorities into clinical practice and drug development This is supported by others reporting that, despite significant correlations between patients’ subjective severity assessment of acne scarring and HRQOL, doctors’ acne scarring severity assessments do not correlate strongly with patients’ own assessments of severity or HRQOL impact [26]. Accordingly, PRO measures are currently being used in medical product development to support labeling claims [12].

In summary, this study highlights the significant psychosocial impact of atrophic acne scars. Individuals with mild scars also expressed significant impact on quality of life that increases with aggravation of scar severity. These data suggest that PROs provide unique information on the physical, functional, and psychological impact of acne scarring from the patient’s perspective. Therefore, inquiry of patient-reported severity and disease impact using HRQOL measures is warranted to more completely characterize the disease burden, assess treatment efficacy, and direct patient management.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was sponsored by Galderma. Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Dr. Maria Angeles Brooks and Dr. Nihar Masurkar, Kantar Health (France) and funded by Galderma. The authors thank the study participants for their participation in this study.

Declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Galderma.

Conflict of interest

JT has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and received grants/honoraria from Almirall, Boots Walgreens, Bausch, Cipher, Galderma, L'Oreal, and Sun. SB has acted as an advisor for AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co, Actelion Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Almirall-Hermal GmbH, Amgen GmbH, Celgene GmbH, Galderma Laboratorium GmbH, Janssen-Cilag GmbH, Leo Pharma GmbH, Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Menlo Therapeutics, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Pfizer Pharma GmbH, Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH, and UCB Pharma GmbH, and has received speaker honorarium from Novartis Pharma GmbH, AbbVie, MSD, Pfizer, Janssen-Cilag, La Roche-Posay, Actelion, GSK, BMS, Celgene, Almirall, and Hexal-Sandoz. FCB has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and received grants/honoraria from Almirall, Cassiopea, Foamix Pharmaceuticals, Galderma, and Ortho Dermatologics. RC is an employee of Galderma. JH has acted as an advisor, consultant, and/or speaker and received honoraria from Almirall, BioPharmX, Cassiopeia, Cutanea, Cutera, Dermira, EPI Health, Galderma, La Roche-Posay, Ortho Dermatologics, Sol Gel, Sun, and Vyne. AH has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and received grants/honoraria from Allergan, Cassiopea, Galderma, GSK, La Roche-Posay, Novan, Ortho Dermatologics, Regeneron Sanofi, and Vyne. EL has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and received grants/honoraria from AbbVie, Aclaris Therapeutics Inc., Allergan Inc., Almirall, AstraZeneca, Athenix, Biopelle Inc., BioPharmX, Biorasi LLC, BMS, Brickell Biotech Inc., Cassiopea S.p.A., Celgene, Cellceutix, ChemoCentryx, Cutanea Life Sciences, Demira, Dow Pharmaceutical Sciences Inc., Dr Reddy's Laboratory, Eli Lilly and Company, Gage Development Company LLC, Galderma Laboratories L.P., Galderma USA, Hovione, Kadmon Corporation LLC, La Roche-Posay, LEO Pharma, Medimmune, Menlo Therapeutics, Moleculin LLC, Neothetics, Nielsen Holdings N.V,, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer Inc., Promius Pharma LLC, Sebacia Inc., Sienna Labs Inc., SkinCeuticals LLC, Sol-Gel Technologies, UCB, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC. AL has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and received grants/honoraria from Galderma, GSK, L’Oreal, La Roche-Posay, Origimm, Leo Pharma, and Proctor & Gamble. MR has acted as an advisor and/or speaker and received honoraria from Eucerin, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Leo Pharma. JW has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and received grants/honoraria from Almirall, Bausch, Cassiopea, Cutera, EPI Health, Foamix, Galderma, and Ortho Dermatologics. BD has acted as an advisor, consultant, and/or speaker and received honoraria from BMS, Galderma, La Roche-Posay, Merck Serono, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi.

Availability of data and material

A copy of the study questionnaire is available on request. Individual data cannot be shared for privacy reasons.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

JT, BD, RC: made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work and the analysis or interpretation of data; drafted the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. SB, FC-B, JH, AH, EL, AL, MR, JW: made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data; revised the work critically for important intellectual content; approved the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval

The Kantar Independent Review Board/Ethics Committee conducted a detailed review of the study and reached a favorable opinion on the 30th of September 2021 (retrospective approval).

Consent to participate

All participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, Dreno B, Finlay A, Leyden JJ, et al. Management of acne: a report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(1 Suppl):S1–37. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, Dréno B, Kang S, Leyden JJ, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5 Suppl):S1–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin AR, Lookingbill DP, Botek A, Light J, Thiboutot D, Girman CJ. Health-related quality of life among patients with facial acne—assessment of a new acne-specific questionnaire. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26(5):380–385. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, Bolliger IW, Dellavalle RP, Margolis DJ, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Investig Dermatol. 2014;134(6):1527–1534. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Layton AM, Henderson CA, Cunliffe WJ. A clinical evaluation of acne scarring and its incidence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(4):303–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan J, Kang S, Leyden J. Prevalence and risk factors of acne scarring among patients consulting dermatologists in the USA. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(2):97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poli F, Dreno B, Verschoore M. An epidemiological study of acne in female adults: results of a survey conducted in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(6):541–545. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeung CK, Teo LH, Xiang LH, Chan HH. A community-based epidemiological study of acne vulgaris in Hong Kong adolescents. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82(2):104–107. doi: 10.1080/00015550252948121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(2):246–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18131897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilgen E, Derya A. There is no correlation between acne severity and AQOLS/DLQI scores. J Dermatol. 2005;32(9):705–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman GJ. Management of post-acne scarring. What are the options for treatment? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1(1):3–17. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. US Food & Drug Administration. 2009. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-reported-outcome-measures-use-medical-product-development-support-labeling-claims. Accessed 03 Mar 2021.

- 13.Bhate K, Williams HC. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(3):474–485. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan JK, Tang J, Fung K, Gupta AK, Thomas DR, Sapra S, et al. Development and validation of a comprehensive acne severity scale. J Cutan Med Surg. 2007;11(6):211–216. doi: 10.2310/7750.2007.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Layton A, Dréno B, Finlay AY, Thiboutot D, Kang S, Lozada VT, et al. New patient-oriented tools for assessing atrophic acne scarring. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6(2):219–233. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0098-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oosthuizen P, Lambert T, Castle DJ. Dysmorphic concern: prevalence and associations with clinical variables. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;32(1):129–132. doi: 10.3109/00048679809062719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan JCR, Leclerc M, York J, Dréno B. The burden of acne scars: a qualitative study on patient experience. In: EADV 29th Congress; New Frontiers in Dermatology and Venereology P0052; 2020.

- 19.Basra MKA, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994–2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(5):997–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuah SY, Goh CL. The impact of post-acne scars on the quality of life among young adults in Singapore. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8(3):153–158. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.167272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chularojanamontri L, Sethabutra P, Kulthanan K, Manapajon A. Dermatology life quality index in Thai patients with systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77(6):683–687. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.86481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassan J, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D, Richards H, Yates VM. The individual health burden of acne: appearance-related distress in male and female adolescents and adults with back, chest and facial acne. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(8):1105–1118. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellett SC, Gawkrodger DJ. The psychological and emotional impact of acne and the effect of treatment with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140(2):273–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips KA, Castle DJ. Body dysmorphic disorder in men. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed). 2001;323(7320):1015–1016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7320.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ball HL. Conducting online surveys. J Hum Lact. 2019;35(3):413–417. doi: 10.1177/0890334419848734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas CL, Kim B, Lam J, Richards S, See A, Kalouche S, et al. Objective severity does not capture the impact of rosacea, acne scarring and photoaging in patients seeking laser therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):361–366. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.