Abstract

Oxidation reactions are fundamental transformations in organic synthesis and chemical industry. With oxygen or air as terminal oxidant, aerobic oxidation catalysis provides the most sustainable and economic oxidation processes. Most aerobic oxidation catalysis employs redox metal as its active center. While nature provides non-redox metal strategy as in pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ)-dependent methanol dehydrogenases (MDH), such an effective chemical version is unknown. Inspired by the recently discovered rare earth metal-dependent enzyme Ln-MDH, here we show that an open-shell semi-quinone anionic radical species in complexing with lanthanum could serve as a very efficient aerobic oxidation catalyst under ambient conditions. In this catalyst, the lanthanum(III) ion serves only as a Lewis acid promoter and the redox process occurs exclusively on the semiquinone ligand. The catalysis is initiated by 1e--reduction of lanthanum-activated ortho-quinone to a semiquinone-lanthanum complex La(SQ-.)2, which undergoes a coupled O-H/C-H (PCHT: proton coupled hydride transfer) dehydrogenation for aerobic oxidation of alcohols with up to 330 h−1 TOF.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Homogeneous catalysis

A decade ago the first rare-earth-metal dependent enzyme was discovered, in which a non-redox lanthanide ion is central in the active site of a methanol dehydrogenase. Inspired by this discovery, here the authors show that an open-shell semi-quinone anionic radical species, complexed with lanthanum, could serve as a very efficient aerobic oxidation catalyst under ambient conditions.

Introduction

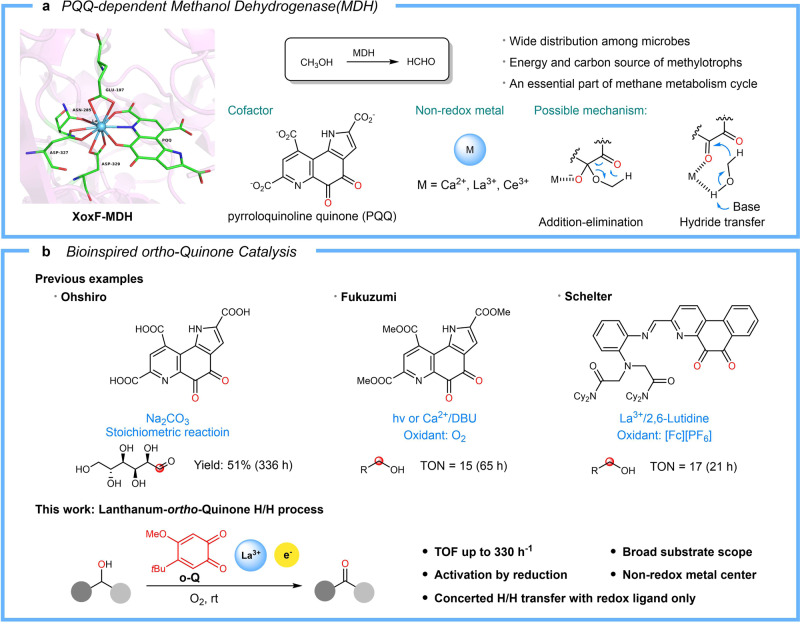

Rare-earth metals are in fact not rare but widely distributed in earth crust and lanthanides such as La and Ce are as abundant as Cu and Zn1. In the living sphere, nature has evolved effective strategies in utilizing earth crust metals as active centers in enzymes. However, a rare earth-metal dependent enzyme was not discovered till 2011, when the first lanthanide enzyme, Ln-MDH was discovered in methylotrophic bacterial by Kawai2,3. Ln-MDH is a lanthanide-dependent methanol dehydrogenase (MDH)4–6, closely resembling its calcium counterpart first discovered in 19677–9. Both MDHs contains a redox-active cofactor, pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) where the oxidation reaction takes place. Mechanistically, the redox cycle between PQQ and its natural substrate methanol proceeds through either an addition-elimination process with a hemiacetal intermediate or direct hydride transfer (Fig. 1a). In both cases, the active sites metals are believed to serve as only non-redox Lewis acid promoter10–15. This mechanistic scenario of Ln-MDH is distinctive from the established alcohol oxidation catalysts wherein redox-active metals such as Pd16–20, Cu21–28, and Fe29–32 are involved.

Fig. 1. Aerobic oxidation of alcohols.

a Left: active sites of XoxF-methanol dehydrogenase (La-MDH) (PDB ID: 6adm). Right: overview of methanol dehydrogenase. b Bio-inspired ortho-quinone catalysis. Upper: previous reports about redox properties of PQQ model compounds. Lower: overview of this work.

The unique mechanistic feature of MDH has drawn significant efforts in pursuing bio-inspired catalysis. Ohshiro demonstrated the synthetic application of PQQ in the oxidation of glucose33–37. Fukuzumi reported a model study of PQQ ester-Ca(ClO4)2 in the aerobic oxidation of alcohols10,11. Schelter synthesized a La-MDH model complex and investigated its catalytic performance in the dehydrogenation of benzyl alcohol with ferricenium ion as an oxidant38. In the latter two cases, efficient catalytic turnover was only observed in the presence of strong organic base (Note: During the revision of this article, a PQQ biomimetic work (Chem. Eur. J. 27, 10087-10098 (2021)) demonstrated the oxidation of 4-methyl benzylalcohol still proceeded without DBU, albeit with lower yield), but the efficiency was still too low to be of any synthetic utility, particularly when comparing with the redox-metal catalysts such as Pd16–20 or Cu-nitroxyl21–28 catalytic system in aerobic oxidation. To achieve effective quinone catalysis remains an open challenge from the synthetic point of view, in spite of the ubiquitous existence of quinone-enzyme in nature. Recently, we and others have developed bio-inspired ortho-quinone catalysts with the cofactor of copper amine oxidase, TPQ39 as a blueprint for the oxidation of amines40–62.

In this work, we report an ortho-quinone/lanthanum complex as highly effective aerobic oxidation catalyst. An open-shell semiquinone anionic radical species in complexing with lanthanum(III) ion is found to serve as the catalytically active species for the oxidation of alcohols under aerobic conditions. The catalysis is initialized by 1e--reduction of lanthanum-activated ortho-quinone o-Q to a semiquinone-lanthanum complex La(o-Q-.)2, which undergo a concerted dehydrogenation for aerobic oxidation of alcohols with up to 330 h−1 TOF (Fig. 1b).

Results and discussion

Establishment of optimal condition

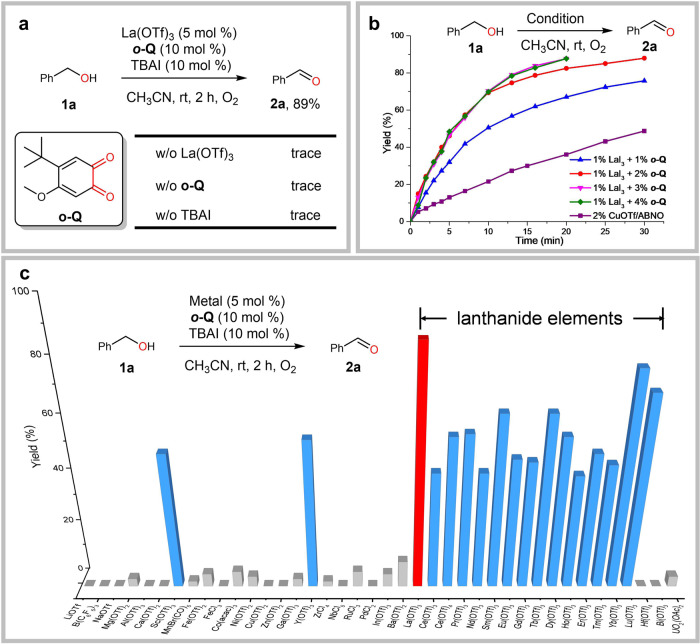

We initially found that a three-component system composed of La(OTf)3, ortho-quinone o-Q (for the performance of other quinones, see Supplementary Fig. 1) and n-Bu4NI was active for the aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohol 1a (Fig. 2a). A survey of different metal salts indicated all rare earth metals (REE) worked well in the reactions with lanthanum(III) ion as the optimal choice in terms of yields (Fig. 2c). In contrast, other metals including base metals such as Mg2+, Li+, Ca2+ or redox metals such as Cu2+, Fe3+ or Pd2+ showed rather poor activity or were even inert (Fig. 2c). We quickly identified LaI3 as the optimal choice in lieu of La(OTf)3 and iodide additive and the two-component catalyst LaI3/o-Q was even more active. The reaction reached to completion in 20 mins with only 1 mol% loading of LaI3-(o-Q)2 (standard condition) (Fig. 2b), showing significantly improved activity over the best Cu/nitroxyl system (CuOTf/ABNO)25. The optimal ratio of La/o-Q was determined to be 1:2 and further increasing the loading of quinone did not lead to any further improvement (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. Selected reaction details.

a Control experiment. b Kinetic profile of the reaction. CuOTf/ABNO condition: benzyl alcohol 1a (0.4 mmol), Cu(MeCN)OTf (2 mol %), 4-MeObpy (2 mol %), ABNO (0.4 mol %), NMI (4 mol %), MeCN (4 mL), room temperature, O2 balloon. c Metal screening (for details, see Supplementary Table 1). Unless noted, reactions were conducted on a 0.4 mmol scale with 0.6 mL MeCN at room temperature under 1 atm O2, and yields were determined by GC using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard. TBAI = Tetrabutylammonium iodide. ABNO = 9-Azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane N-oxyl.

Scopes

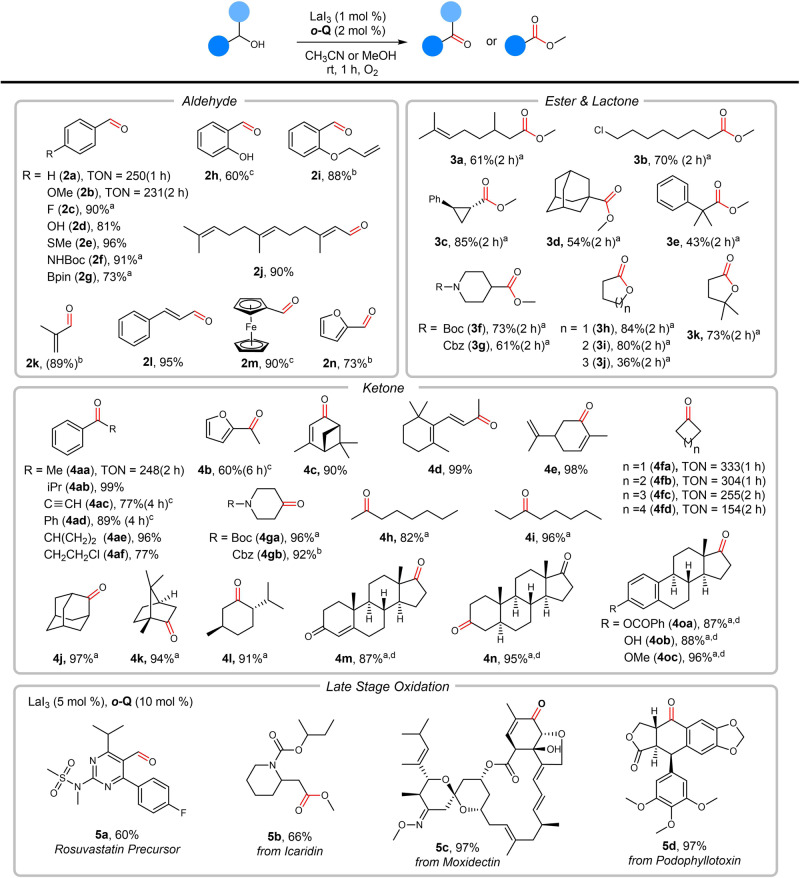

The substrate scope was then explored under the optimal reaction conditions. The reactions worked well with para-substituted benzyl alcohols bearing either electron-donating (Figs. 3, 2a, b, i) or electron-withdrawing substituents (2c). The reaction also tolerated functional groups such as thioether (2e), amine (2 f), boronic acid ester (2 g), and free phenols (2d and 2 h), to note that free phenols didn’t work well in the Cu/TEMPO catalysis system24. Heterocyclic aromatic alcohols such as ferrocene methanol (2 m) and furfuryl alcohol (2n) and allylic alcohols (2j-l) could be equally applied in the current catalysis.

Fig. 3. Substrate scope.

Unless otherwise noted, reactions were conducted on a 1 mmol scale with 1 mL MeCN (for aldehyde, lactone and ketone) or MeOH (for ester) at room temperature under 1 atm O2, and yields were determined by flash column chromatography. Yields in parentheses were determined by 1H NMR. For late stage oxidation, reactions were conducted on 0.2 mmol scale with LaI3 (5 mol%), o-Q (10 mol%) at room temperature under 1 atm O2 and yields were determined by flash column chromatography (for details, see Supplementary Information). aLaI3 (2 mol%), o-Q (4 mol%). bLaI3 (4 mol%), o-Q (8 mol%). cLa(OTf)3 (5 mol%), o-Q (10 mol%), nBu4NI (15 mol%) for 2 h. dMeCN/DCM (v/v = 1:1, 0.5 M).

The reactions with aliphatic alcohols have also been examined to give a mixture of aldehyde and ester (from self-condensation). When the reaction was conducted in methanol, a sole formation of methyl ester could be achieved. Selected examples including long-chain alkyl (3a and 3b), cyclopropyl (3c), bulky alkyl (3d and 3e) and piperidinyl (3f and 3g) were listed in Fig. 3, showing moderate to good activity. Diols such as 1,4-butanediol, 1,5-pentanediol and 1,6-hexanediol could be converted into the corresponding lactones (3h-k) with moderate to high yields. The catalysis also worked extremely well with secondary alcohols including aromatic (4aa-af), allylic alcohols such as verbenol and carveol (4c-e), acyclic (4h-i) and cyclic secondary alcohols (4fa-gb). The alcohols oxidation with testosterone (4 m), androsterone (4n) and estradiol derivates (4oa-oc) went well under this catalysis. Several pharmaceutical intermediates and pesticides were also tested to demonstrate the applicability of our catalysis in the late stage functionalization. Activated benzyl alcohol (Rosuvastatin precursor, 5a) and primary aliphatic alcohol (Icaridin, 5b) would be oxidized to corresponding aldehyde and ester with moderate yields. And secondary alcohol (Moxidectin, 5c and Podophyllotoxin, 5d) proceeded well with nearly quantitative yields. Large scale oxidations were also conducted and more than 200 turnover numbers could be achieved in one hour for benzylic alcohol (2a) and both aromatic and aliphatic alcohols (4aa and 4fa).

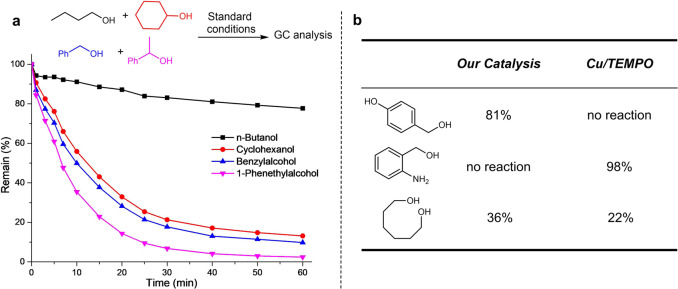

A competitive one-pot experiment was conducted to investigate the chemoselectivity (Fig. 4a). It was noted that the reaction rates with secondary alcohol cyclohexanol and those activated primary alcohols such as benzyl alcohol and 1-phenethylalcohol are comparable and they reacted much faster than aliphatic alcohol such as 1-butanol. In comparison, the typical Cu/TEMPO showed significantly preference to primary alcohols over secondary alcohols24. Our quinone catalytic system could tolerate free phenol but not free anilines, which is distinctive from Cu-TEMPO system (Fig. 4b). In oxidizing sluggish 1,6-hexanediol, the quinone catalyst performed slightly better than Cu/ABNO system26.

Fig. 4. Comparison of our catalyst system with Cu/TEMPO system.

a Competition experiments monitored by GC analysis. Standard conditions: LaI3 (0.004 mmol), o-Q (0.008 mmol), each alcohol substrates (0.1 mmol), MeCN (0.6 mL), room temperature, O2 balloon. b Comparison of our catalyst system and Cu/TEMPO system.

Control experiments

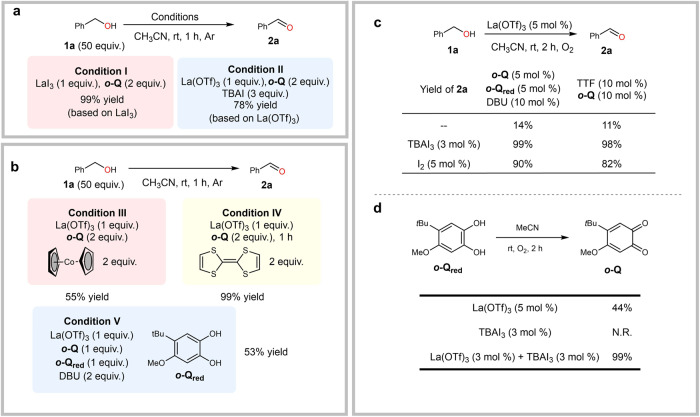

The real active catalytic species was first investigated. In control experiments, removing any of the three catalytic species, o-Q, La(OTf)3 or TBAI completely shut down the reaction (Fig. 2a), which implied La3+, ortho-quinone catalyst and iodide additive were all essential for this aerobic oxidation. Stoichiometric reactions with either LaI3-o-Q or La(OTf)3-o-Q-TBAI proceeded smoothly under argon (Fig. 5a, Condition I and II), suggesting that the substrate-oxidizing active specie was generated from LaI3 and o-Q, and oxygen served as the terminal oxidant for the recycling of the catalyst.

Fig. 5. Control experiment.

a Stochiometric reactions. b Other in situ generated semiquinone species control experiments. Yields were based on the amount of La3+. c, d Role of iodine. TTF = tetrathiafulvalene. DBU = 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene. TBAI3 = tetrabutylammonium triiodide.

Characterizations and verification of the active species

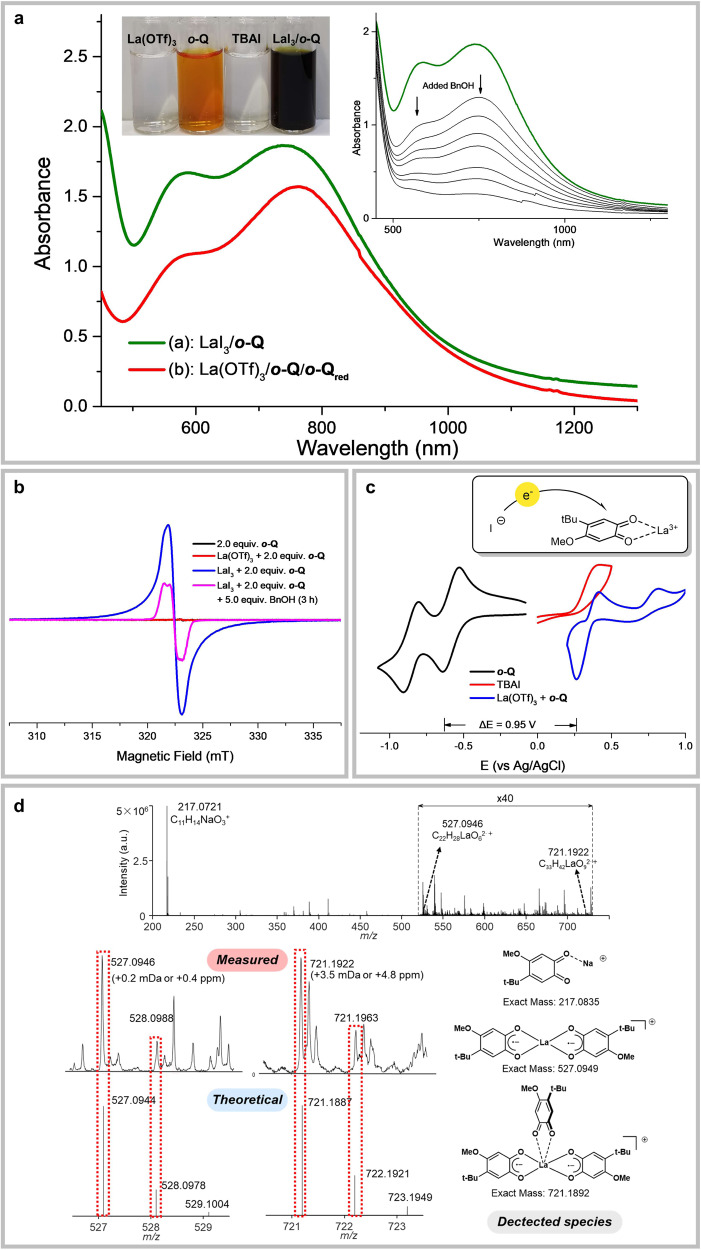

Dramatic color change was noted during the reaction process. When iodide additive was added to a solution of La(OTf)3 and o-Q, or upon mixing LaI3 with o-Q, an instant color change from red to dark green was observed (Fig. 6a) and the color changed back to red when the reaction was complete. UV–visible spectrum of the dark green solution indicated a new absorption at 570 and 750 nm. Previously, similar absorptions were reported for semiquinone radical anion in the presence of metal ion such as Sc(III) or Zn(II) (Fig. 6a)63,64. It should be noted a Ce-MDH was crystallized with their active site existed in the form of a Ce(III)-semiquinone anionic radical complex65. However, its mechanistic relevance remains obscure. EPR spectrum of the catalytic system confirmed the existence of an organic radical species with g = 2.003 (peak-to-peak linewidth is 1.2 mT) (Fig. 6b), and the simulation supported a semiquinone radical in coordination with La(III) (Supplementary Fig. 2)66. In comparison, no obvious EPR signal was detected with only ortho-quinone.

Fig. 6. Characterization of active species.

a UV–Vis spectrum. Sample concentration: 1.0 mM in MeCN. (a): LaI3 (1.0 mM) and o-Q (2.0 mM); (b): La(OTf)3 (1.0 mM), o-Q (1.0 mM), o-Qred (1.0 mM), DBU (2.0 mM). Inset: The time profile of stoichiometric benzyl alcohol quenching experiment. (Supplementary Fig. 5). b EPR spectrum. Sample concentration: LaI3 (0.1 M) and o-Q (0.2 M) in MeCN at 298 K. c CV test. Sample concentration: 4.0 mM in electrolyte solution (0.1 M nBu4NPF6 in MeCN). d High-resolution mass spectrum of LaI3 and o-Q in MeCN at 298 K.

Cyclic voltammograms (CV) of o-Q showed a reduction peak at −0.63 V (vs Ag/AgCl), and this was shifted to 0.32 V (vs Ag/AgCl) in the presence of La(OTf)3, a positive shift as large as 0.95 V (Fig. 6c). All the other REE metals also showed large but varied positive shift of the reduction potential of o-Q (Supplementary Fig. 3). Hence, the coordination of quinone by coordination to lanthanides38 could dramatically facilitate its single electron oxidation of iodide (TBAI) (Eox = 0.39 V vs Ag/AgCl). In comparison, the redox potential gap between free o-Q and TBAI was 1.03 V, largely disfavored for electron transfer67, and we did not observe any obvious change when mixing only o-Q and TBAI. Next, reductive initiators other than iodide have been tested and the addition of cobaltocene or tetrathiafulvalene could also initiate the stochiometric reaction with comparable activity (Fig. 5b, Condition III and IV).

Furthermore, the oxidation could also proceed when equal amount of o-Q and hydroquinone o-Qred were employed, such a combination was known to be able to generate semiquinone radical anionic species under basic conditions and this was verified by UV–vis in our case (Fig. 6a and Fig. 5d, Condition V)64. Moreover, adding benzyl alcohol into the dark green solution of LaI3/(o-Q)2 showed gradually decrease of adsorption as monitored by UV–visible spectroscopy (Fig. 6a) and increasingly formation of benzaldehyde was observed by GC (Supplementary Fig. 5). Similar quenching of the EPR signal was also clearly noted (Fig. 6b), indicating the consumption of the semiquinone intermediate. Taken together, these results strongly supported the involvement of the reductively generated semiquinone anionic radical in the active catalytic cycle and iodide served as a single electron donor for reductive generation of the active species.

We have tried to elucidate the structure of the La(III)-semiquinone complex in both solid and solution phase. Unfortunately, efforts to determine the solid structure by crystalizing the possible complex have been in vain. We then investigated the solution phase complexation between lanthanum (III) and semiquinones by ESI-MS. The MS spectra showed several signals clearly indicating the existence of La-semiquinone complexes (Fig. 6d). We were able to identify a major peak at 527.0946, ascribing to the expected 1:2 complex of La(o-Q-.)2+ (Fig. 6d). A minor peak at 721.1922 could also be assigned as La(o-Q-.)2+ binding with an additional neutral o-Q, an indication of dynamic and multi- binding behavior between La(III) and quinone/semiquinone.

Proposed catalytic cycle

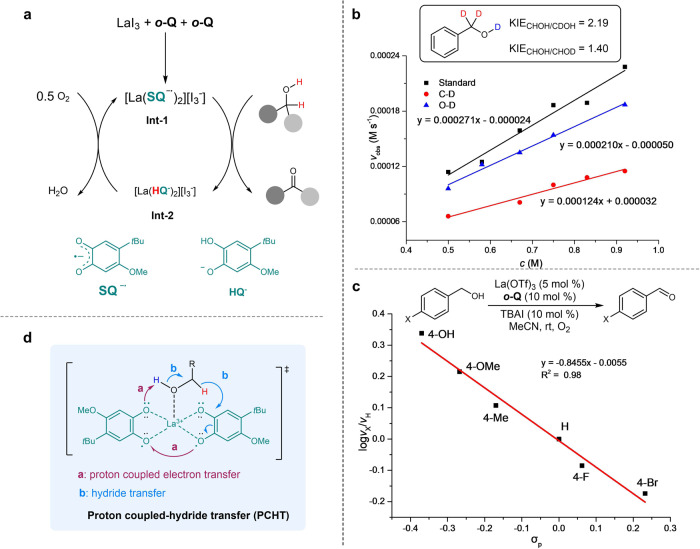

Based on the above experimental observations, a catalytic cycle was proposed as shown in Fig. 7a. After coordinating with LaI3, o-Q would be reduced by iodide anion via SET to form a radical dianion complex (Int-1) involving a La(III) metal center coordinated with at least two molecules of semiquinone radical anion SQ–∙. Alcohol would then coordinate with lanthanum center, following by oxidative dehydrogenation to afford the corresponding aldehyde or ketone. Ester and lactone could be formed via second dehydrogenation from a semi-acetal intermediate. The reduced hydroquinone HQ– complex (Int-2) would be re-oxidized by oxygen to regenerate Int-1 (Fig. 7a). In the kinetic analysis of the reaction progress, we observed product inhibition effect (Supplementary Fig. 14), adding support to the coordination mode. In addition, the preference for ester formation with aliphatic alcohols can also be explained by the relatively strong binding of aliphatic aldehyde with lanthanum metal comparing with benzaldehyde.

Fig. 7. Proposed catalytic cycle and kinetic studies.

a Proposed catalytic cycle. b Kinetic isotope effects of benzyl alcohol 1a. c Hammett correlation of para-substituted benzyl alcohols. d Proposed proton-coupled hydride transfer model.

Mechanism of the dehydrogenation process

In Fukuzumi and Schelter’s biomimic quinone catalysis, organic base was essential to facilitate the oxidative process and the reactions were believed to proceed via a stepwise deprotonation and hydride transfer mechanism, and the latter step may follow either an addition-elimination or direct hydride transfer pathway. In our case, no obvious base effect was observed (Supplementary Table 6) and KIE effect was found on both O–H and C–H of benzylic alcohol (KIEO–H = 1.40, KIEC–H = 2.19) (Fig. 7b)68–70. These observations were supportive of a coupled O–H/C–H hydrogen transfers instead of stepwise deprotonation and hydride transfer. Each of the two semiquinone moieties SQ–∙ may concurrently accept a hydrogen (Fig. 7a). A Hammett plot with para-substituted benzyl alcohols revealed a preference for electron-rich substitutions with ρ = −0.84 (Fig. 7c), suggesting that positive charge was developing during H-transfer, an indication of hydride transfer. At this point, the detailed H-transfer mechanism remains to be elucidated, pending further structural characterization of the active intermediate (e.g. Int-1 or Int-2). We proposed a proton-coupled hydride transfer (PCHT) pathway to account for the experimental observations (Fig. 7d). Concerted H-atom transfer, though can not be completely excluded, was unlikely considering the rather low BDE of hydroquinone o-Qred (75 kcal/mol by DFT vs 96 kcal/mol for C-H bond in methanol). The absence of radical-rearrangement products with radical-probe substrates (e.g. 2i, 3c, and 4fa) also disproved the existence of discrete radical intermediates during hydrogen-transfer, and is in support of hydride transfer. Preliminary DFT calculations were conducted to support the proposed PCHT pathway (Supplementary Fig. 16).

Inspired by natural lanthanide-dependent enzyme, Ln-MDH, we have developed in this work an efficient LaI3/ortho-quinone aerobic oxidation catalyst for alcohol oxidation. The lanthanide-ortho-quinone catalysis demonstrated high activity over a broad range of alcohols, providing practical accesses to aldehydes, ketones as well as esters. Mechanistic studies uncovered that a lanthanum complex with semiquinone radical anion served as the real active catalytic species and the dehydrogenation proceeded most likely via proton coupled-hydride transfer. Though semiquinone radicals are frequently observed in quinoproteins, their function remains obscure. This study implies a possible functioning mode of semiquinone radicals beyond simply positing as a recycling intermediate of quinone cofactors. From the synthetic point of view, the reductive activation strategy as well as the resulted radical anion as redox ligand provides a new twist in exploring aerobic oxidation catalysis.

Method

General procedure for alcohol oxidation

A flame-dried 10 mL flask was flushed with O2 and equipped with an O2 balloon. LaI3 (5.19 mg, 0.01 mmol) were added to the solution of o-Q (3.88 mg, 0.02 mmol) and alcohol (1.0 mmol) in 1.0 mL of CH3CN. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. After the reaction was completed, the crude reaction product was purified though a silica gel using 1:10-1:5 EtOAc/petro ether to give a pure product. For some volatile aldehyde, yields were determined by 1H NMR.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Jin-Pei Cheng and Prof. Lei Jiao for helpful discussions. This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (21861132003 and 22031006 to S. L.) and Tsinghua University Initiative Scientific Research Program for financial support. S.L. is supported by the National Program of Top-notch Young Professionals.

Source data

Author contributions

S.L. conceived and directed the project. Ruipu Z. optimized the reaction conditions, examined the substrate scope and studied the mechanism with the help of Runze Z., L.Z., and M.-T.Z. L.Z. carried out DFT calculation. R.J. and Runze Z. carried out HRMS analyzation with the help of Y.Xia. Ruipu Z. and S.L. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Martine Largeron and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work

Data availability

All other data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-28102-4.

References

- 1.Cheisson T, Schelter EJ. Rare earth elements: Mendeleev’s bane, modern marvels. Science. 2019;363:489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.aau7628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hibi Y, et al. Molecular structure of La3+-induced methanol dehydrogenase-like protein in methylobacterium radiotolerans. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2011;111:547–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitriyanto NA, et al. Molecular structure and gene analysis of Ce3+-induced methanol dehydrogenase of Bradyrhizobium sp. MAFF211645. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2011;111:613–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keltjens JT, Pol A, Reimann J, Op den Camp HJM. PQQ-dependent methanol dehydrogenases: rare-earth elements make a difference. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;98:6163–6183. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5766-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotruvo JA. The chemistry of lanthanides in biology: recent discoveries, emerging principles, and technological applications. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019;5:1496–1506. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daumann LJ. Essential and ubiquitous: the emergence of lanthanide metallobiochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:12795–12802. doi: 10.1002/anie.201904090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anthony C. Quinoprotein-catalysed reactions. Biochem. J. 1996;320:697–711. doi: 10.1042/bj3200697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsushita K, et al. Quino-proteins: structure, function, and biotechnological applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002;58:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s00253-001-0851-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anthony C. The Quinoprotein dehydrogenases for methanol and glucose. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004;428:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itoh S, Kawakami H, Fukuzumi S. Modeling of the chemistry of quinoprotein methanol dehydrogenase. oxidation of methanol by calcium complex of coenzyme PQQ via addition−elimination mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:439–440. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itoh S, Kawakami H, Fukuzumi S. Model studies on calcium-containing quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenases. catalytic role of Ca2+ for the oxidation of alcohols by coenzyme PQQ (4,5-dihydro-4,5-dioxo-1H-pyrrolo[2,3-f]quinoline-2,7,9-tricarboxylic acid) Biochemistry. 1998;37:6562–6571. doi: 10.1021/bi9800092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Reddy SY, Bruice TC. Mechanism of methanol oxidation by quinoprotein methanol dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:745–749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610126104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prejano M, Marino T, Russo N. How can methanol dehydrogenase from methylacidiphilum fumariolicum work with the alien Ce(III) ion in the active center? a theoretical study. Chem.-Eur. J. 2017;23:8652–8657. doi: 10.1002/chem.201700381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lumpe H, Pol A, Op den Camp HJM, Daumann LJ. Impact of the lanthanide contraction on the activity of a lanthanide-dependent methanol dehydrogenase—a kinetic and DFT study. Dalton Trans. 2018;47:10463–10472. doi: 10.1039/c8dt01238e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picone N, Op den Camp HJ. Role of rare earth elements in methanol oxidation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019;49:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson KP, Larock RC. Palladium-catalyzed oxidation of primary and secondary allylic and benzylic alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3185–3189. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimura T, Onoue T, Ohe K, Uemura S. Palladium(II)-catalyzed oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes and ketones by molecular oxygen. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:6750–6755. doi: 10.1021/jo9906734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brink G-J, Arends IWCE, Sheldon RA. Green, catalytic oxidation of alcohols in water. Science. 2000;287:1636–1639. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigman MS, Jensen DR. Ligand-modulated palladium-catalyzed aerobic alcohol oxidations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:221–229. doi: 10.1021/ar040243m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung K, et al. Chemoselective Pd-catalyzed oxidation of polyols: synthetic scope and mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:7593–7602. doi: 10.1021/ja4008694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semmelhack MF, Schmid CR, Cortes DA, Chou CS. Oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes with oxygen and cupric ion, mediated by nitrosonium ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:3374–3376. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gamez P, Arends IWCE, Reedijk J, Sheldon RA. Copper(II)-catalysed aerobic oxidation of primary alcohols to aldehydes. Chem. Commun. 2003;2003:2414–2415. doi: 10.1039/b308668b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumpulainen ET, Koskinen AM. Catalytic activity dependency on catalyst components in aerobic copper-TEMPO oxidation. Chem.—Eur. J. 2009;15:10901–10911. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoover JM, Stahl SS. Highly practical copper(I)/TEMPO catalyst system for chemoselective aerobic oxidation of primary alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:16901–16910. doi: 10.1021/ja206230h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steves JE, Stahl SS. Copper(I)/ABNO-catalyzed aerobic alcohol oxidation: alleviating steric and electronic constraints of Cu/TEMPO catalyst systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:15742–15745. doi: 10.1021/ja409241h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie X, Stahl SS. Efficient and selective Cu/nitroxyl-catalyzed methods for aerobic oxidative lactonization of diols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:3767–3770. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badalyan A, Stahl SS. Cooperative electrocatalytic alcohol oxidation with electron-proton-transfer mediators. Nature. 2016;535:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature18008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCann SD, Lumb J-P, Arndtsen BA, Stahl SS. Second-order biomimicry: in situ oxidative self-processing converts Copper(I)/diamine precursor into a highly active aerobic oxidation catalyst. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017;3:314–321. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin W, et al. Iron chloride/4-acetamido-TEMPO/sodium nitrite-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of primary alcohols to the aldehydes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma S, et al. Development of a general and practical iron nitrate/TEMPO-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes/ketones: catalysis with table salt. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011;353:1005–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang X, Zhang J, Ma S. Iron catalysis for room-temperature aerobic oxidation of alcohols to carboxylic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:8344–8347. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang X, Liu J, Ma S. Iron-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of alcohols: lower cost and improved selectivity. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2019;23:825–835. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Itoh S, Mure M, Ohshiro Y. Oxidation of D-glucose by coenzyme PQQ: 1,2-enediolates as substrates for PQQ oxidation. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1987;1987:1580–1581. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohshiro Y, et al. Micelle enhanced oxidation of amines by coenzyme PQQ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:3465–3468. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Itoh S, Kato N, Ohshiro Y, Agawa T. Oxidative decarboxylation of α-amino acids with coenzyme PQQ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:4753–4756. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itoh S, Kato N, Ohshiro Y, Agawa T. Catalytic oxidation of thiols by coenzyme PQQ. Chem. Lett. 1985;14:135–136. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mure M, Suzuki A, Itoh S, Ohshiro Y. Oxidative Cα–Cβ fission (dealdolation) of β-hydroxy amino acids by coenzyme PQQ. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1990;1990:1608–1611. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McSkimming A, Cheisson T, Carroll PJ, Schelter EJ. Functional synthetic model for the lanthanide-dependent quinoid alcohol dehydrogenase active site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:1223–1226. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janes SM, et al. A new redox cofactor in eukaryotic enzymes: 6-hydroxydopa at the active site of bovine serum amine oxidase. Science. 1990;248:981–987. doi: 10.1126/science.2111581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Largeron M, Neudorffer A, Fleury MB. Oxidation of unactivated primary aliphatic amines catalyzed by an electrogenerated 3,4-azaquinone species: a small-molecule mimic of amine oxidases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:1026–1029. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Largeron M, Chia-roni A, Fleury MB. Environmentally friendly chemoselective oxidation of primary aliphatic amines by using a biomimetic electrocatalytic system. Chem. -Eur. J. 2008;14:996–1003. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Largeron M, Fleury MB. A biologically inspired Cu(I)/topaquinone-like co-catalytic system for the highly atom-economical aerobic oxidation of primary amines to imines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:5409–5412. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Largeron M, Fleury MB. A metalloenzyme-like catalytic system for the chemoselective oxidative cross-coupling of primary amines to imines under ambient conditions. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015;21:3815–3820. doi: 10.1002/chem.201405843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Largeron M, Fleury MB. A bioinspired organocatalytic cascade for the selective oxidation of amines under air. Chem.—Eur. J. 2017;23:6763–6767. doi: 10.1002/chem.201701402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wendlandt AE, Stahl SS. Chemoselective organocatalytic aerobic oxidation of primary amines to secondary imines. Org. Lett. 2012;14:2850–2853. doi: 10.1021/ol301095j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wendlandt AE, Stahl SS. Bioinspired aerobic oxidation of secondary amines and nitrogen heterocycles with a bifunctional quinone catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:506–512. doi: 10.1021/ja411692v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wendlandt AE, Stahl SS. Modular o-quinone catalyst system for dehydrogenation of tetrahydroquinolines under ambient conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:11910–11913. doi: 10.1021/ja506546w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li B, Wendlandt AE, Stahl SS. Replacement of stoichiometric DDQ with a low potential o-quinone catalyst enabling aerobic dehydrogenation of tertiary indolines in pharmaceutical intermediates. Org. Lett. 2019;21:1176–1181. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qin Y, Zhang L, Lv J, Luo S, Cheng J-P. Bioinspired organocatalytic aerobic C-H oxidation of amines with an ortho-quinone catalyst. Org. Lett. 2015;17:1469–1472. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang R, Qin Y, Zhang L, Luo S. Mechanistic studies on bioinspired aerobic C-H oxidation of amines with an ortho-quinone catalyst. J. Org. Chem. 2019;84:2542–2555. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.8b02948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goriya Y, Kim HY, Oh K. o-Naphthoquinone-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of amines to (ket)imines: a modular catalyst approach. Org. Lett. 2016;18:5174–5177. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Golime G, Bogonda G, Kim HY, Oh K. Biomimetic oxidative deamination catalysis via ortho-naphthoquinone-catalyzed aerobic oxidation strategy. ACS Catal. 2018;8:4986–4990. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nguyen KM, Largeron M. A bioinspired catalytic aerobic oxidative C-H functionalization of primary aliphatic amines: synthesis of 1,2-disubstituted benzimidazoles. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015;21:12606–12610. doi: 10.1002/chem.201502487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang R, Qin Y, Zhang L, Luo S. Oxidative synthesis of benzimidazoles, quinoxalines, and benzoxazoles from primary amines by ortho-quinone catalysis. Org. Lett. 2017;19:5629–5632. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim K, Kim HY, Oh K. Aerobic oxidation approaches to indole-3-carboxylates: a tandem cross coupling of amines-intramolecular mannich-oxidation sequence. Org. Lett. 2019;21:6731–6735. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Si T, Kim HY, Oh K. Substrate promiscuity of ortho-naphthoquinone catalyst: catalytic aerobic amine oxidation protocols to deaminative cross-coupling and N-nitrosation. ACS Catal. 2019;9:9216–9221. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pawar SA, Chand AN, Kumar AV. Polydopamine: an amine oxidase mimicking sustainable catalyst for the synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles under aqueous conditions. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019;7:8274–8286. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Largeron M, Deschamps P, Hammada K, Fleury M-B. A dual biomimetic process for the selective aerobic oxidative coupling of primary amines using pyrogallol as a precatalyst. Isolation of the [5 + 2] cycloaddition redox intermediates. Green Chem. 2020;22:1894–1905. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thorvea PR, Maji B. Aerobic primary and secondary amine oxidation cascade by a copper amine oxidase inspired catalyst. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021;11:1116–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thorvea PR, Maji B. Deaminative olefination of methyl n-heteroarenes by an amine oxidase inspired catalyst. Org. Lett. 2021;23:542–547. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c04060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Largeron M. Aerobic catalytic systems inspired by copper amine oxidases: recent developments and synthetic applications. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:4722–4730. doi: 10.1039/c7ob00507e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang R, Luo S. Bio-inspired quinone catalysis. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2018;29:1193–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yuasa J, Fukuzumi S. Thermochromism of the disproportionation equilibrium of π-dimer radical anion complexes bridged by scandium ions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:642–644. doi: 10.1039/b316234f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ulas G, Lemmin T, Wu Y, Gassner GT, DeGrado WF. Designed metalloprotein stabilizes a semiquinone radical. Nature Chem. 2016;8:354–359. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bogart JA, Lewis AJ, Schelter EJ. DFT study of the active site of the XoxF-type natural, cerium-dependent methanol dehydrogenase enzyme. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015;21:1743–1748. doi: 10.1002/chem.201405159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Witwicki M, Jezierska J. DFT insight into o-semiquinone radicals and Ca2+ ion interaction: structure, g tensor, and stability. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2013;132:1383. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheng J-P, Lu Y, Zhu X, Mu L. Energetics of multistep versus one-step hydride transfer reactions of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) models with organic cations and p-quinones. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:6108–6114. doi: 10.1021/jo9715985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mueller JA, Goller CP, Sigman MS. Elucidating the significance of β-hydride elimination and the dynamic role of acid/base chemistry in a palladium-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9724–9734. doi: 10.1021/ja047794s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schultz MJ, Adler RS, Zierkiewicz W, Privalov T, Sigman MS. Using mechanistic and computational studies to explain ligand effects in the palladium-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:8499–8507. doi: 10.1021/ja050949r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoover JM, Ryland BL, Stahl SS. Mechanism of Copper(I)/TEMPO-catalyzed aerobic alcohol oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:2357–2367. doi: 10.1021/ja3117203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All other data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request. Source data are provided with this paper.