Abstract

Introduction

Microneedling (MN) is a minimally invasive procedure involving the induction of percutaneous wounds with medical-grade needles. In this literature review, we investigate clinical data on MN for the treatment of hair loss disorders.

Methods

A literature search was conducted through PubMed up to November 2021 to identify original articles evaluating the use of MN on hair loss disorders. The database was searched using the following keywords: “microneedling,” “micro needling,” “micro needle,” “microneedle,” “needle,” “dermaroller” and “alopecia,” “hair loss,” “alopecia,” “areata,” “cicatricial,” or “effluvium.”

Results

A total of 22 clinical studies featuring 1127 subjects met our criteria for inclusion. Jadad scores ranged from 1 to 3, with a mean of 2. As an adjunct therapy, MN improved hair parameters across genders and a range of hair loss types, severities, needling devices, needling depths of 0.50–2.50 mm, and session frequencies from once weekly to monthly. Across 17 investigations totaling 911 androgenic alopecia (AGA) subjects, MN improved hair parameters when paired with 5% minoxidil, growth factor solutions, and/or platelet-rich plasma (PRP) topicals, or when introduced to subjects whose hair count changes had plateaued for ≥ 6 months on other treatments. Across four investigations on 201 alopecia areata (AA) subjects, MN improved hair parameters as a standalone therapy versus cryotherapy, as an adjunct to 5-aminolevulinic acid and photodynamic therapy, and equivalently when paired with topical PRP versus carbon dioxide laser therapy with topical PRP. Across 657 subjects receiving MN, no serious adverse events were reported.

Conclusions

Clinical studies demonstrate generally favorable results for MN as an adjunct therapy for AGA and AA. However, data are of relatively low quality. Significant heterogeneity exists across interventions, comparators, and MN procedures. Large-scale randomized controlled trials are recommended to discern the effects of MN as a standalone and adjunct therapy, determine best practices, and establish long-term safety.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-021-00653-2.

Keywords: Microneedling, Alopecia, Hair loss

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| There is growing interest in the use of microneedling as a standalone and adjunct therapy for hair loss disorders. |

| This literature reviews summarizes a body of clinical evidence on microneedling for hair loss disorders to evaluate hair loss outcomes, evidence quality, limitations in research, and areas of opportunity for future investigations. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Microneedling improves hair loss parameters across a range of hair loss types, needling devices, needling depths, session frequencies, and combination therapies. |

| While evidence suggests that microneedling might improve hair loss, clinical data are of relatively low quality. With better study designs and efforts to standardize best practices, microneedling could become a staple adjuvant to US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved hair loss treatments. |

Introduction

Alopecia is a common cosmetic concern affecting over 50% of adults throughout a lifetime [1]. Hair loss disorders are typically categorized into scarring and nonscarring alopecias, with treatments dependent on the pathogenesis and diagnosis determined during dermatological evaluation [2]. While drug and nondrug interventions often help to improve many hair loss disorders, treatments for androgenic alopecia (AGA) are typically relegated to stopping the progression of the condition [3]. Moreover, treatments for alopecia areata (AA) and alopecia totalis (AT) remain limited, with recurrence rates high [4]. Consequently, there remains demand for novel and effective hair loss treatments.

Microneedling (MN) is a minimally invasive procedure involving the induction of percutaneous wounds with 0.25–5.00 mm medical-grade needles. First described by Orentreich in 1995 for the use of wrinkles and atrophic scars, MN purportedly releases platelet-derived growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor to promote wound-healing responses, improve angiogenesis, and attenuate or partially reverse fibrosis resulting from acute injury and skin aging [5, 6]. MN can be administered at-home or in-clinic, with devices ranging from needling stamps, manual rollers, and automated pens with or without fractional radiofrequency. Across a range of devices, needling depths, and session frequencies, MN has demonstrated clinical improvements as a standalone and/or adjunct therapy for patients with atrophic scars, actinic keratoses, and pigmentation disorders such as vitiligo and melasma [6, 7].

In the last decade, studies have demonstrated that MN may enhance transdermal delivery, promote anagen-initiating Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and improve dermal papillae stem cell proliferation—thus potentiating therapeutic effects for a variety of hair loss disorders [8–10]. In 2013, the landmark study by Dhurat et al. on 100 AGA subjects found that over a 12-week period, once-weekly MN combined with twice-daily 5% minoxidil increased hair counts significantly versus minoxidil monotherapy [11]. Since then, investigators have continued to assess the effects of MN as both a standalone and adjunct therapy for hair loss.

In this systematic review, we investigate the use of MN as a standalone, adjunct, and comparator therapy on hair loss disorders. We evaluate patient populations, interventions, comparators, MN procedures, outcomes, and adverse events—as well as evidence quality using Jadad scoring. We discuss possible mechanisms by which MN may improve hair loss disorders as a monotherapy and an adjunct intervention. Finally, we identify limitations in the current body of research and provide recommendations for future clinical trials.

Methods

Literature Search

A broad literature search was conducted through PubMed up to November 2021 to identify original articles that evaluate the use of MN on hair loss disorders. The database was searched using combinations of the following keywords: “microneedling,” “micro needling,” “micro needle,” “microneedle,” “needle,” “dermaroller” and “alopecia,” “hair loss,” “alopecia,” “areata,” “cicatricial,” or “effluvium.” This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All search hits were screened and examined for relevant titles and abstracts. Full texts were reviewed to determine eligibility. Articles were included if they featured all of the following: (a) human subjects with scalp hair loss, (b) MN as a standalone or adjunct therapy, and (c) endpoint measurements related to scalp hair. Articles were excluded if they did not feature (a) original data, (b) human data, (c) endpoint measurements for hair parameters, and/or (d) designs that adequately evaluated the effects of MN on hair. This literature review is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

PICOS inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Parameter | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Patients of any age treated for scalp hair loss | |

| Intervention | MN as a standalone or adjunct therapy | MN devices with needle-releasing drugs, acupuncture needles |

| Comparator | How effective is MN at improving hair loss outcomes? | |

| Outcomes | Primary endpoints: phototrichogram, investigator, and/or patient assessments | Any study not designed to adequately test for the standalone or additive effect of MN |

| Study design | Prospective studies | Retrospective design, case series, literature reviews, or nonhuman subjects; studies with fewer than five patients; ongoing clinical trials; Jadad scores lower than 1 |

A table summarizing the inclusion and exclusion criteria in our systematic review for clinical studies investigating the use of MN for the treatment of hair loss disorders

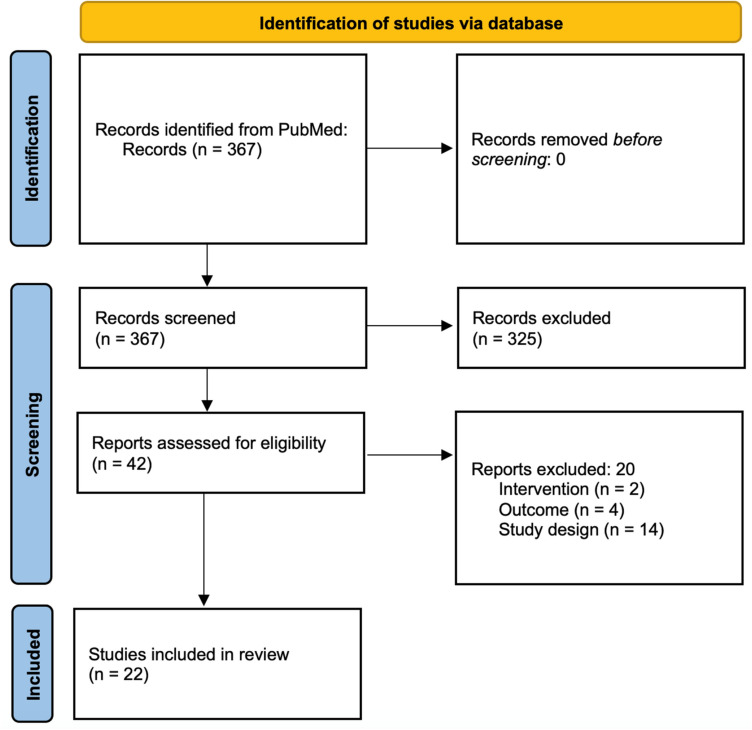

RE and SR each independently identified 367 records for screening. RE, SR, and PD each independently screened all 367 titles and abstracts to assess eligibility, and the 42 full texts to determine inclusion. RE, SR, and PD each independently assessed Jadad scores. Any disagreements in identifications, screenings, selections, and/or Jadad scores were discussed by RE and PD and resolved by RE.

Results

Of the 42 full texts accessed to assess eligibility, 20 were excluded on the basis of the wrong intervention (n = 2), outcome (n = 4), or study design (n = 14). A total of 22 clinical studies met our criteria for inclusion: 17 trials with randomization and 5 nonrandomized prospective cohorts (Fig. 1). Jadad scores ranged from 1 to 3, with a mean score of 2 (Table S1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart. A PRISMA flowchart detailing the process of eligibility for all records reviewed for the literature review, as well as the number of studies identified, screened, excluded, and included

Of the 22 studies, 16 were conducted on AGA subjects, 4 on alopecia areata subjects, 1 on alopecia totalis subjects, and 1 on both AGA and telogen effluvium (TE) subjects. A total of 1127 subjects (856 males and 269 females) were included featuring the following hair loss types: AGA (n = 911), AA (n = 201), AT (n = 8), and TE (n = 7) [11–32].

AGA

Patients

Within studies featuring AGA subjects, enrollment ages ranged from 18 to 70 years, with a subject-weighted average of 33.75 years. Of the 15 studies with male AGA subjects, 1 did not enroll subjects based on a classification system, while 14 included males with hair loss based on the Norwood–Hamilton scale: I (0.0%), II (46.7%), III (93.3%), IV (93.3%), V (60%), and VI (26.7%). Of the seven studies with female AGA subjects, one did not enroll subjects based on any classification system, one enrolled based on Sinclair scores, and five enrolled females with hair loss determined by the Ludwig scale: I (80.0%), II (60.0%), and III (60.0%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Parameter summaries for studies assessing the use of MN on AGA subjects

| Androgenic alopecia (AGA) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Total subjects (sex); alopecia type | Study type | Treatment regimen | MN procedure | No. of MN sessions | Treatment duration | Endpoints | Effectiveness | Adverse events | Jadad score |

| Ramadan et al. [12] | n = 126 (46 m, 80 f); AGA | Combination: PRP, 5% minoxidil, 2.50 mg finasteride (men), 200 mg spironolactone (women) |

Group 1: medications + PRP injections Group 2: medications + MN + topical PRP Group 3: medications |

MN automated pen, 2.00 mm needles, session endpoints marked as three passes followed by PRP application | 6, once every month | 6 months | Hair counts, hair diameters, photographic evaluation |

Yes, in both sexes Hair density increased in group 2 versus group 1; larger effect for groups 1 and 2 versus group 3 |

No serious events reported Twenty-three subjects reported transient pain after PRP |

2 |

| Sohng et al. [13] | n = 29 (24 m, 5 f); AGA | Combination: 5% minoxidil |

Group 1: home-use MN Group 2: home-use MN + 5% minoxidil Group 3: 5% minoxidil |

MN stamp, 0.25 mm spiral needles, endpoint sessions marked as gentle tapping 20 times in target area | 52, twice weekly | 6 months | Hair counts, self assessments | No | No serious events reported; mild and transient pruritus noted in one subject | 2 |

| Burns et al. [14] | n = 11 (f); AGA | Combination: 5% minoxidil + MN added to ongoing hair loss treatments | 5% minoxidil + MN twice per month added to ongoing hair loss treatments | MN automated pen, session endpoints marked as two passes across the frontal, crown, vertex, and upper-parietal scalp | 6, twice every month | 3 months | Photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Investigators noted that 11/11 subjects improved at least 1–1.5 Sinclair scores |

No serious events reported | 1 |

| Gowda et al. [15] | n = 90 (m); AGA | Combination: 5% minoxidil, PRP |

Group 1: 5% minoxidil Group 2: 5% minoxidil + MN Group 3: 5% minoxidil + PRP injections |

MN roller, 1.50 mm needles, session endpoints marked as passes longitudinally, vertically, and diagonally until pinpoint bleeding noted | 4, once every month | 4 months | Hair counts, photographic evaluation |

Yes Hair counts increased in groups 1, 2, and 3; investigators noted improvements in group 3 |

No serious events reported in MN group | 1 |

| Shome et al. [16] | n = 50 (25 m, 25 f); AGA | Combination: intradermal versus MN delivery of growth factor solution |

Group 1: intradermal QR678 Neo(®) Group 2: MN + QR678 Neo(®) topical |

MN roller, 1.50 mm needles, session endpoints marked as 4–5 passes longitudinally, vertically, and diagonally until light erythema noted | 8, once every 3 weeks | 12 months | Hair counts, hair diameters, photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Hair counts and hair diameters increased in groups 1 and 2; no difference in changes to hair counts and diameters in group 1 versus 2 |

No serious events reported; transient scalp itchiness higher in group 2 | 2 |

| Ozcan et al. [17] | n = 62 (m); AGA | Combination: PRP solution |

Group 1: PRP injections Group 2: MN + PRP solution |

MN automated pen, 1.50 mm needles | 4, once every two weeks then once after 1 month | 10 weeks | Hair counts, hair diameters, pull tests, photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Hair counts and hair diameters increased in groups 1 and 2; changes to anagen:telogen hairs increased in group 2 versus group 1 |

No events reported | 2 |

| Yu et al. [18] | n = 40 (m); AGA | Combination: 5% minoxidil, growth factors |

Group 1: saline + MN Group 2: 5% minoxidil + MN Group 3: growth factors + MN Group 4: 5% minoxidil + growth factors + MN |

MN roller | 16, once weekly | 16 weeks | Hair counts, hair diameters, photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Hair density increased in groups 2, 3, and 4 |

No serious events reported Three subjects developed mild erythema which alleviated after 24 hours |

3 |

| Bao et al. [19] | n = 75 (m); AGA | Combination: 5% minoxidil |

Group 1: 5% minoxidil Group 2: MN Group 3: 5% minoxidil + MN |

MN automated pen, 1.00–2.00 mm needles, session endpoints marked as hemorrhage and redness | 8, once every 3 weeks | 24 weeks | Hair counts, hair diameters, photographic evaluation |

Yes Hair counts increased in groups 1, 2, and 3; hair density increased in groups 2 and 3; larger improvements for group 3 versus groups 1 and 2 |

Twelve events related to scalp irritation were noted; all resolved within 4 days; no differences in occurrence across groups | 3 |

| Aggarwal et al. [20] | n = 30 (m); AGA | Split scalp: MN, PRP |

Side 1: MN Side 2: MN + PRP injections |

MN roller, 1.50–2.00 mm needles, session endpoints marked as gentle rolling until pinpoint bleeding | 4, once monthly | 6 months | Hair counts, hair diameters, self assessments |

Yes Hair counts and hair diameters increased in sides 1 and 2; no difference in change of hair counts and hair diameters in side 1 versus side 2 |

No serious events reported | 3 |

| Faghihi et al. [21] | n = 59 (29 m, 30 f); AGA | Combination: 5% minoxidil |

Group 1: 5% minoxidil Group 2: 5% minoxidil + MN 1.2 mm Group 3: 5% minoxidil + MN 0.6 mm |

MN automated pen, 1.20 or 0.60 mm needles, session endpoints marked as pinpoint bleeding | 6, once every 2 weeks | 12 weeks | Hair counts, hair diameters, photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Hair counts and diameters increased in groups 1, 2, and 3; change in hair counts and diameters greater in group 3 versus group 1; change in hair diameters greater in group 2 versus group 1 |

More pain reported from MN in group 2 versus 3 | 2 |

| Starace et al. [22] | n = 50 (14 m, 36 f); AGA, TE | Combination: MN added to ongoing hair loss treatments | MN every 3 weeks added to ongoing hair loss treatments | MN roller, 1.50 mm needles, 20–25 minute sessions, session endpoints marked as eight passes longitudinally, vertically, and diagonally in affected regions or until mild erythema and pinpoint bleeding noted | 3, once every 4 weeks | 6 months | Hair counts, hair diameters, photographic evaluation, self assessments |

AGA: yes, in both sexes TE: yes Hair counts and hair diameters increased |

No serious events reported | 1 |

| Kumar et al. [23] | n = 60 (m); AGA | Combination: 5% minoxidil |

Group 1: 5% minoxidil Group 2: 5% minoxidil + MN |

MN roller, 1.50 mm needles, session endpoints marked as passes longitudinally, vertically, and diagonally in affected regions until pinpoint bleeding noted | 8; four sessions (month 1), two sessions (month 2), two sessions (month 3) | 12 weeks | Hair counts, photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Hair counts increased in group 2 versus group 1; higher self assessment scores in group 2 versus group 1 |

No serious events reported | 2 |

| Yu et al. [24] | n = 19 (m); AGA | Split scalp: 5% minoxidil |

Side 1: 5% minoxidil Side 2: 5% minoxidil + fractional radiofrequency MN |

Fractional radiofrequency MN, 1.50 mm needles | 5, once every 4 weeks | 5 months | Hair counts, hair diameters, photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Hair counts and hair diameters increased in sides 1 and 2; changes to hair counts and diameters greater in side 2 versus 1 |

No serious events reported | 3 |

| Bao et al. [25] | n = 60 (m); AGA | Combination: 5% minoxidil |

Group 1: 5% minoxidil Group 2: MN Group 3: 5% minoxidil + MN |

MN automated pen, 1.50–2.50 mm needles, session endpoints marked as 3–4 passes until redness and/or hemorrhaging noted | 12, once every 2 weeks | 24 weeks | Hair counts, hair diameters, photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Hair counts increased in groups 1, 2, and 3; hair counts, hair diameters, photographic evaluations, and self assessments better in group 3 versus groups 1 and 2 |

No serious events reported; no differences in adverse event reporting across groups | 3 |

| Shah et al. [26] | n = 50 (m); AGA | Combination: 5% minoxidil, PRP |

Group 1: 5% minoxidil Group 2: 5% minoxidil + MN + PRP injections |

MN roller, 1.50 mm needles, session endpoints marked as eight passes longitudinally, vertically, and diagonally in affected regions or until mild erythema | 6, once monthly | 6 months | Photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Photographic evaluations better in group 2 versus group 1 |

No events reported | 2 |

| Dhurat et al. [11] | n = 100 (m); AGA | Combination: 5% minoxidil |

Group 1: 5% minoxidil Group 2: 5% minoxidil + MN |

MN roller, 1.50 mm needles, session endpoints marked as passes longitudinally, vertically, and diagonally in affected regions until mild erythema | 12, once weekly | 3 weeks | Hair counts, photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Hair counts increased in groups 1 and 2; hair counts increased in group 1 versus 2; higher photographic evaluations and self assessments in group 1 versus 2 |

No serious events reported | 3 |

| Lee et al. [27] | n = 11 (f); AGA | Split scalp: growth factor solution |

Side 1: growth factor solution + MN Side 2: saline + MN |

MN automated pen, 0.50 mm needles | 5, once weekly | 5 weeks | Hair counts, self assessments |

Yes Hair counts increased in side 1 versus side 2 |

No events reported | 1 |

A table summarizing all included studies assessing the use of MN on AGA subjects. Each study summary features parameters regarding author, year of publication, total subjects, gender, study type, treatment regimen, MN procedure, number of MN sessions, treatment duration, assessment endpoints, effectiveness, adverse events, and Jadad score

Interventions and Comparators

In total, 536 subjects received MN therapy, while 375 received other hair loss interventions. Across all study groups, MN was included as a standalone therapy in 6 groups (n = 105). As an adjunct therapy, MN was evaluated alongside topical minoxidil in 10 groups (n = 234), proprietary topicals and/or growth factor solutions in 3 groups (n = 46), PRP in 2 groups (n = 61), continued medication use in 1 group (n = 50), PRP and systemic medications in 1 group (n = 42), PRP with topical minoxidil in 1 group (n = 25), topical minoxidil and continued medications in 1 group (n = 11), and topical minoxidil alongside growth factors in 1 group (n = 10) (Table 2).

MN Procedures

MN devices tested included manual rollers (n = 8), automated pens (n = 7), manual stamps (n = 1), and automated fractional radiofrequency pens (n = 1). Needle lengths ranged from 0.25 to 2.50 mm, with a mean needle length of 1.39 mm.

The frequency of MN sessions ranged from twice weekly to once monthly, with a mean session frequency of once per 2.64 weeks. The number of MN sessions ranged from 3 to 52, with a mean of 9.53 MN sessions per study. Treatment durations averaged 20.01 weeks.

While four studies did not specify MN session endpoints, 13 studies standardized endpoints by a number of passes, directions, and/or taps (n = 3), mild erythema (n = 3), a number of passes and/or bleeding (n = 3), or passes until hemorrhage (n = 4) (Table 2).

Outcomes

In total, 15 of 17 studies assessed hair parameters through phototrichograms (i.e., hair counts, hair diameters, and/or hair densities). Of the 17 studies, 6 included MN-only groups, whereas all studies tested MN alongside other hair loss interventions.

Of the six MN monotherapy groups, two noted significant increases to total hair counts, one found significant increases to hair diameters and total hair density, and three showed no effect [13, 18–20, 25, 27].

Of the seven studies testing MN with 5% minoxidil, six found statistically significantly increased hair counts versus 5% minoxidil alone, and for a range of devices and needle lengths: rollers, automated pens, and fractional radiofrequency devices with depths from 0.60 to 2.50 mm [11, 15, 18, 19, 21, 23, 25]. However, Sohng et al. tested 5% minoxidil with a 0.25 mm needling stamp twice-weekly and found no effect on hair parameters [13]. When comparing 5% minoxidil with 0.60 mm or 1.20 mm needle lengths, Faghihi et al. found that 0.60 mm needle lengths led to significant hair count and diameter increases versus 5% minoxidil, whereas 1.20 mm needle lengths only saw hair count increases versus 5% minoxidil [21].

All three studies testing MN alongside proprietary topicals and/or growth factors noted increases to hair counts [16, 18, 27]. Lee et al. and Yu et al. demonstrated improved hair parameters but no differences across groups when comparing MN use with topical versus intradermal delivery of proprietary products and/or growth factors [18, 27]. Conversely, Ozcan et al. found that MN alongside either topical or injectable PRP significantly increased hair counts and diameters similarly across groups, but that subjects receiving MN alongside topical PRP saw greater improvements to anagen:telogen hairs [17]. Interestingly, in a split-scalp study, Aggarwal et al. showed that both MN and MN with PRP injections increased hair diameters and density equivalently—with no significant differences noted across groups [20].

Two studies tested the introduction of MN alongside ongoing hair loss medications [14, 22]. Burns et al. found that twice monthly MN combined with 5% minoxidil improved Ludwig scores for 11/11 females who had previously plateaued for ≥ 6 months on other hair loss treatments [14]. Starace et al. showed that the addition of MN improved hair counts in those already using hair loss treatments for > 1 year (Table 2) [22].

Adverse Events

Across 536 subjects receiving MN, no serious adverse events were reported. Of mild adverse events, transient pain, scalp irritation, and mild erythema were most commonly reported. Withdrawal rates across MN groups were low and comparable to non-MN groups.

AA and AT

Patients

Of the five studies with AA and AT subjects, enrollment ages ranged from 16 to 45 years, with a subject-weighted average of 28.34 years. Three investigations enrolled subjects with hair loss gradients according to Severity Of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score, one study enrolled on the basis of severe AA, and one study enrolled on the basis of AT (Table 3).

Table 3.

Parameter summaries for studies assessing the use of MN on AA and AT subjects

| Alopecia areata (AA), alopecia totalis (AT) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Total subjects (gender); alopecia type | Study type | Treatment regimen | MN procedure | No. of MN sessions | Treatment duration | Endpoints | Effectiveness | Adverse events | Jadad score |

| Aboeldahab et al. [28] | n = 80 (50 m, 30 f); alopecia areata (AA) | Comparison: cryotherapy versus MN |

Group 1: cryotherapy Group 2: MN |

MN automated pen, 1.00–2.00 mm needles, session endpoints marked as 4–5 passes longitudinally, vertically, and diagonally | 6, once every 2 weeks | 12 weeks | Hair counts, hair density, Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores, photographic evaluation, self assessments |

Yes Hair counts, hair density, SALT scores, photographic evaluation, and self assessments improved in groups 1 and 2; higher changes to SALT scores in group 2 versus 1 |

No adverse events in group 2 | 3 |

| Ragab et al. [29] | n = 60 (48 m, 12 f); AA | Combination: PRP solution |

Group 1: PRP injections Group 2: fractional CO2 laser + PRP topical Group 3: MN + PRP topical |

MN roller, 1.50 mm needles, session endpoints marked as 4–5 passes longitudinally, vertically, and obliquely until mild erythema noted | 3, once monthly | 3 months | SALT |

Yes SALT scores improved in groups 1, 2, and 3; no difference in SALT scores across groups |

No serious events reported; pain higher in group 1 versus group 3 | 3 |

| Abdallah et al. [30] | n = 20 (19 m, 1 f); AA | Intrapatient comparison: triamcinolone acetonide injections, minoxidil 5% injections |

Patch 1: triamcinolone acetonide injections Patch 2: 5% minoxidil injections Patch 3: triamcinolone acetonide injections + 5% minoxidil injections Patch 4: MN Patch 5: control |

MN roller, session endpoints marked as 4–5 passes longitudinally, vertically, and diagonally | 4, once every 4 weeks | 16 weeks | SALT, Lesional Area & Density (LAD) scores |

Yes SALT and LAD scores decreased in patches 1, 2, 3, and 4; largest differences seen in patches 1 and 3 versus patch 5 |

No serious events reported | 2 |

| Giorgio et al. [31] | n = 41 (17 m, 24 f); AA | Combination: 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy |

Group 1: MN Group 2: 5-aminolevulinic acid + photodynamic therapy Group 3: MN + 5-aminolevulinic acid + photodynamic therapy |

MN automated pen, 1.00 mm needles, session endpoints marked as 5 minute of passes on AA-affected areas | 6, once every 3 weeks | 18 weeks | 4-point scale |

Yes No change in group 1; improvements noted in 53% of group 2 and 94% of group 3 |

No events reported | 1 |

| Yoo et al. [32] | n = 8 (2 m, 6 f); alopecia totalis (AT) | Split scalp: 5-aminolevulinic acid + photodynamic therapy |

Side 1: MN + methyl 5-aminolevulinic acid + photodynamic therapy Side 2: methyl 5-aminolevulinic acid + photodynamic therapy |

MN roller, 5.00 mm needles | 3, once every 4 weeks | 12 weeks | Histological assessments (4 mm punch biopsy) | No | No serious events reported | 1 |

A table summarizing all included studies assessing the use of MN on AA and AT subjects. Each study summary features parameters regarding author, year of publication, total subjects, gender, study type, treatment regimen, MN procedure, number of MN sessions, treatment duration, assessment endpoints, effectiveness, adverse events, and Jadad score

Interventions and Comparators

In total, 114 subjects received MN therapy while 95 received other hair loss interventions. Of the five studies featuring AA and AT subjects, three compared treatments across patients (n = 181), while two compared treatments across lesions within the same patients (n = 28).

Across all study groups, MN was included as a standalone therapy in three groups (n = 68). As an adjunct therapy, MN was evaluated alongside a PRP topical in one group (n = 20), and with 5-aminolevulinic acid or methyl 5-aminolevulinic acid alongside photodynamic therapy in two groups (n = 25). As a comparator, MN was included as a control against cryotherapy in one group (n = 40), PRP injections in one group (n = 20), fractional CO2 laser alongside a PRP topical in one group (n = 20), triamcinolone acetonide injections in one group (n = 20), 5% minoxidil injections in one group (n = 20), and 5-aminolevulinic acid or methyl 5-aminolevulinic acid alongside photodynamic therapy in two groups (n = 23) (Table 3).

MN Procedures

MN devices tested included manual rollers (n = 3) and automated pens (n = 2). Needle lengths ranged from 1.00 to 5.00 mm, with a mean needle length of 2.25 mm.

The frequency of MN sessions ranged from once every 2 weeks to once monthly, with a mean session frequency of once every 3.46 weeks. The number of MN sessions ranged from three to six, with a mean of 4.40 MN sessions per study. Treatment durations averaged 14.20 weeks.

While one study did not specify MN session endpoints, four studies standardized endpoints by a number of passes (n = 2), a number of passes and/or mild erythema (n = 1), or minutes of passes in affected areas (n = 1) (Table 3).

Outcomes

In total, two of five studies assessed hair parameters through objective measurements (i.e., phototrichograms or 4 mm punch biopsies). Subjective measurements for the remaining three studies included Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores (n = 2), Lesional Area & Density (LAD) scores (n = 1), and/or a four-point scale (n = 1).

Of the three studies testing standalone MN groups, Aboeldahab et al. and Abdallah et al. showed that MN alone increased hair density and improved SALT scores, respectively [28, 30]. However, Giorgio et al. demonstrated no changes to hair parameters using a four-point scale to evaluate MN alone [31].

When comparing MN with cryotherapy, Aboeldahab et al. found significant increases to hair counts and hair densities across both interventions, with MN demonstrating greater changes to SALT scores versus cryotherapy [28]. Conversely, Abdallah et al. found that triamcinolone acetonide injections with and without 5% intradermal minoxidil led to greater improvements to SALT and LAD scores versus controls than MN alone [30].

As an adjunct therapy, Giorgio et al. showed that MN alongside 5-aminolevulinic acid and photodynamic therapy improved 94% of AA lesions versus 53% of lesions receiving only 5-aminolevulinic acid and photodynamic therapy [31]. However, Yoo et al. found that in AT subjects, methyl 5-aminolevulinic acid and photodynamic therapy with and without MN led to no hair parameter improvements according to 4 mm punch biopsies [32].

Finally, Ragab et al. demonstrated that, over a 3-month period, MN alongside topical PRP improves SALT scores similarly to fractional CO2 laser therapy alongside topical PRP (Table 3) [29].

Adverse Events

Among 114 subjects receiving MN, no serious adverse events were reported. Of mild adverse events, transient pain and mild erythema were most common. Of the five studies, no withdrawals were reported in MN or non-MN groups.

Discussion

Clinical studies demonstrate generally favorable results for MN as an adjunct therapy for AGA and AA. However, data are of relatively low quality and should be interpreted with caution. Due to significant heterogeneity across interventions, comparators, and MN procedures (i.e., devices, needle lengths, session frequencies, and session endpoints), we could not conduct a meta-analysis. Here we discuss the proposed mechanisms of MN, limitations in the current body of research, and design considerations for future studies.

Mechanisms

AGA

In AGA-affected hair follicles, dihydrotestosterone dysregulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, induces transforming growth factor β1, and triggers apoptosis in dermal papillae and epithelial cells. This leads to a shortened anagen phase, reductions to dermal papillae cell cluster sizes with each re-entry into anagen and, consequently, microvascular degradation alongside progressive hair follicle miniaturization [33–36]. In mid-to-late stages of miniaturization, perifollicular fibrosis is often observed and may reduce the effectiveness of both systemic and topical AGA treatments [37].

As a monotherapy for AGA, data on MN are limited, and the mechanisms by which MN might improve AGA remain speculative. In a pooled linear regression across six subgroups, Gupta et al. found that MN significantly increased total hair counts, by more than 5% topical minoxidil [38]. However, two of the subgroups were a part of split-scalp studies assessing MN versus PRP injections or topical growth factor solutions [20, 27]. Therefore, the possibility of percutaneous treatment diffusion across scalp zones cannot be discounted.

Animal models suggest that MN may promote anagen-initiating Wnt/β-catenin signaling and dermal papillae stem cell proliferation. In particular, percutaneous wounds from MN appear to activate hair follicle stem cells, platelet-derived growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor—potentiating the initiation of angiogenesis, neocollagenesis, and a new anagen cycle [5–7, 9, 10]. Clinical data show that MN reduces scarring and improves the density and thickness of epidermal and dermal skin layers [39, 40]. In two randomized controlled clinical trials, Bao et al. found that MN alone increased terminal hair counts—with their latter study analyzing biopsies from a subset of AGA subjects showing that MN alone upregulated protein levels of both FZD3 and LEF-1 but not β-catenin [19, 25]. However, RT-PCR testing revealed no statistical increases to mRNA expression—with the authors postulating that the inconsistent results might be due to small sample sizes, infrequent needling sessions, shallow needling depths, and/or posttranscriptional modifications [25].

As an adjunct therapy, MN may improve AGA by enhancing transdermal delivery, and by improving sulfation and Wnt pathway expression when paired with topical minoxidil. Henry et al. demonstrated in vitro that 0.15 mm needles inserted into human skin for 10 seconds enhanced transdermal permeability of calcein by more than 1000-fold [41]. These effects may partly explain the equivalent and/or additive improvements to hair parameters from intradermal growth factors or PRP injections versus MN alongside their topical applications [16, 17]. Additionally, MN may enhance topical minoxidil activation. Topical minoxidil is a pro-drug that requires sulfation by sulfotransferase enzymes in the outer root sheath of hair follicles [8]. Goren et al. demonstrated that reduced sulfotransferase activity in hair follicles predicted topical minoxidil nonresponders [42]. More recently, Sharma et al. found that, over 21 days, once-weekly microneedling led to a median increase in sulfotransferase activity of 37.5% [8]. Finally, Bao et al. demonstrated that MN with 5% minoxidil upregulated the expression of FZD3, LEF-1, and β-catenin in mRNA and protein more than MN or 5% minoxidil monotherapy—suggesting that the addition of MN might amplify the effects of minoxidil on the Wnt pathway [19].

AA and AT

AA and AT are autoimmune forms of alopecia resulting from the collapse of immune privilege in affected hair follicles. In particular, peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrates appear to induce apoptosis in hair follicle keratinocytes—leading to inflammation, impaired hair shaft production, and sometimes hair shaft miniaturization within the same hair cycle. While the histologic features of AA and AT are well studied, their underlying pathogenesis remain poorly understood—with researchers speculating the involvement of immunological shifts related to genetic and environmental factors [4].

As a monotherapy for AA and AT, data on MN are unrobust. While Aboeldahab et al. and Abdallah et al. noted improvements to AA from MN alone, these results should be interpreted with caution due to relatively small sample sizes, as well as the 50% spontaneous recoveries observed in many AA studies with adequate controls [28, 30]. Moreover, Giorgio et al. found no effect from MN alone in AA subjects [31]. As an adjunct therapy, Giorgio et al. suggested that the release of growth factors from MN may induce immunosuppressive actions that amplify the effects of substances such as 5-aminolevulinic acid [31]. Ragab et al. found that MN alongside topical PRP improved hair parameters similarly to PRP injections, and suggested that MN may also enhance transdermal delivery for AA [29].

Limitations

Due to significant heterogeneity across MN studies regarding interventions, comparators, MN devices, needle lengths, session frequencies, and session endpoints, our systematic review does not include a meta-analysis and cannot establish best practices for MN procedures.

Faghihi et al. found hair parameters improved more when pairing 5% minoxidil with fortnightly MN using an automated pen with needle lengths of 0.60 mm versus 1.20 mm [21]. Faghihi et al. postulated that puncture depths of 0.60 mm still generate enough of an inflammatory response for stem cell and growth factor recruitment, but without damaging the hair follicle bulge residing 1.00–1.80 mm from the skin surface [43]. Interestingly, Sasaki found that with MN automated pens, needling lengths matched penetration depths up to 1.50 mm [44]. Due to user pressure variability and needle entry angulation, Lima et al. estimated that a 3.00 mm MN manual roller only penetrates to skin depths 50–70% of its needle length [45]. Taken together, equivalent MN penetration depths of 0.60–0.80 mm may be achievable with MN automated pens and MN manual rollers set to needle lengths of 0.60–0.80 mm and 1.25–1.50 mm, respectively. Relatedly, Fernandes postulated that MN device preferences do not matter so long as the skin is penetrated to the same depths [46]. Regardless of standardizations for MN devices or needle lengths, additional methodological considerations—i.e., session durations, frequencies, and endpoints—still likely exert influence over the degree of inflammation induced, and thereby the magnitude of outcomes across a variety of hair parameters. As such, no procedural best practices can be ascertained with the current body of evidence.

While 8 of 22 clinical studies on MN included groups to evaluate MN alone (n = 174), only 1 study compared MN monotherapy against an untreated control patch for AA (n = 20). Moreover, 21 of 22 clinical studies on MN assessed hair parameter changes over periods of less than 52 weeks. Study durations of less than 52 weeks often do not allow investigators to separate the effects of any intervention against seasonal fluctuations to hair cycling—particularly in the absence of untreated control groups [47, 48].

Finally, 4 out of 22 clinical studies utilized split-scalp study designs to evaluate MN against or as an adjuvant to topicals and/or injectables. Since MN is suspected to enhance transdermal drug delivery, split-scalp study designs leave open the possibility of percutaneous drug diffusion across scalp zones, thus limiting the interpretability of endpoint assessments.

Recommendations

Large-scale, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials assessing the use of MN for hair loss are needed. Future investigations should consider study durations of at least 12 months, include groups for MN as a monotherapy, and evaluate MN against a placebo (i.e., manual rollers with removed needles, automated pens with uninstalled needle cartridges, and/or an untreated control group). Split-scalp studies should be avoided, particularly when evaluating MN against or as an adjuvant to topicals and/or injectables. Finally, studies evaluating the use of MN across different procedural standards (i.e., shorter needle lengths and more frequent sessions versus longer needle lengths and less frequent sessions) will help toward establishing best practices.

Conclusion

Among 22 clinical studies featuring 1127 subjects, MN as an adjunct therapy improved hair parameters across genders as well as a range of hair loss types, hair loss severities, needling devices, needling depths of 0.50–2.50 mm, and session frequencies from once weekly to once monthly—with no serious adverse events reported. However, results should be interpreted with caution due to significant heterogeneity across study interventions, comparators, and MN procedures (i.e., devices, needle lengths, session frequencies, and session endpoints). Large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to discern the effects of MN as a standalone and adjunct therapy, determine best practices for MN procedures, and establish long-term safety data. Study designs should consider 12-month durations, include groups using MN as a monotherapy, and evaluate MN against a placebo and/or untreated group.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

RE contributed to the concept/design, systematic review process, and writing of the manuscript. RE, SR, and PD contributed to the systematic review process.

Disclosures

Robert S. English, Sophia Ruiz, and Pedro DoAmaral have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1.Gan DC, Sinclair RD. Prevalence of male and female pattern hair loss in Maryborough. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10(3):184–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vidal CI. Overview of alopecia: a dermatopathologist's perspective. Mo Med. 2015;112(4):308–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman KD, Rotonda J, Shah AK, Meehan AG. Long-term treatment with finasteride 1 mg decreases the likelihood of developing further visible hair loss in men with androgenetic alopecia (male pattern hair loss) Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18(4):400–406. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trüeb RM, Dias MFRG. Alopecia areata: a comprehensive review of pathogenesis and management. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(1):68–87. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8620-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orentreich DS, Orentreich N. Subcutaneous incisionless (subcision) surgery for the correction of depressed scars and wrinkles. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21(6):543–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1995.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iriarte C, Awosika O, Rengifo-Pardo M, Ehrlich A. Review of applications of microneedling in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:289–298. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S142450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziaeifar E, Ziaeifar F, Mozafarpoor S, Goodarzi A. Applications of microneedling for various dermatologic indications with a special focus on pigmentary disorders: A comprehensive review study. Dermatol Ther. 2021:e15159. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Sharma A, Surve R, Dhurat R, Sinclair R, Tan T, Zou Y, et al. Microneedling improves minoxidil response in androgenetic alopecia patients by upregulating follicular sulfotransferase enzymes. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34(2):659–661. doi: 10.23812/19-385-L-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YS, Jeong KH, Kim JE, Woo YJ, Kim BJ, Kang H. Repeated microneedle stimulation induces enhanced hair growth in a murine model. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(5):586–592. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.5.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito M, Yang Z, Andl T, Cui C, Kim N, Millar SE, et al. Wnt-dependent de novo hair follicle regeneration in adult mouse skin after wounding. Nature. 2007;447(7142):316–320. doi: 10.1038/nature05766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhurat R, Sukesh M, Avhad G, Dandale A, Pal A, Pund P. A randomized evaluator blinded study of effect of microneedling in androgenetic alopecia: a pilot study. Int J Trichol. 2013;5(1):6–11. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.114700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramadan WM, Hassan AM, Ismail MA, El Attar YA. Evaluation of adding platelet-rich plasma to combined medical therapy in androgenetic alopecia. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(5):1427–1434. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sohng C, Lee EH, Woo SK, Kim JY, Park KD, Lee SJ, et al. Usefulness of home-use microneedle devices in the treatment of pattern hair loss. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(2):591–596. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burns LJ, Hagigeorges D, Flanagan KE, Pathoulas J, Senna MM. A pilot evaluation of scalp skin wounding to promote hair growth in female pattern hair loss. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(3):344–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gowda A, Sankey S, Kumar S. Comparative study of efficacy of minoxidil versus minoxidil with platelet rich plasma versus minoxidil with dermaroller in androgenetic alopecia. Int J Res Dermatol. 2021;7(2):279. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shome D, Kapoor R, Vadera S, Doshi K, Patel G, Mohammad KT. Evaluation of efficacy of intradermal injection therapy vs derma roller application for administration of QR678 Neo. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(10):3299–3307. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozcan KN, Sener S, Altunisik N, Turkmen D. PRP application by dermapen microneedling and intradermal point-by-point injection methods, and their comparison with clinical findings and trichoscan in patients. Dermatol Ther. 2021 doi: 10.1111/dth.15182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu CQ, Zhang H, Guo ME, Li XK, Chen HD, Li YH, et al. Combination therapy with topical minoxidil and nano-microneedle-assisted fibroblast growth factor for male androgenetic alopecia: a randomized controlled trial in Chinese patients. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;134(7):851–853. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao L, Zong H, Fang S, Zheng L, Li Y. Randomized trial of electrodynamic microneedling combined with 5% minoxidil topical solution for treating androgenetic alopecia in Chinese males and molecular mechanistic study of the involvement of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Dermatol Treat. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1770162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggarwal K, Gupta S, Jangra RS, Mahendra A, Yadav A, Sharma A. Dermoscopic assessment of microneedling alone versus microneedling with platelet-rich plasma in cases of male pattern alopecia: a split-head comparative study. Int J Trichol. 2020;12(4):156–163. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_64_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faghihi G, Nabavinejad S, Mokhtari F, Fatemi Naeini F, Iraji F. Microneedling in androgenetic alopecia; comparing two different depths of microneedles. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(4):1241–1247. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starace M, Alessandrini A, Brandi N, Piraccini BM. Preliminary results of the use of scalp microneedling in different types of alopecia. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19(3):646–650. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar MK, Inamadar AC, Palit A. A randomized controlled, single-observer blinded study to determine the efficacy of topical minoxidil plus microneedling versus topical minoxidil alone in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2018;11(4):211–216. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_130_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu AJ, Luo YJ, Xu XG, Bao LL, Tian T, Li ZX, et al. A pilot split-scalp study of combined fractional radiofrequency microneedling and 5% topical minoxidil in treating male pattern hair loss. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(7):775–781. doi: 10.1111/ced.13551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bao L, Gong L, Guo M, Liu T, Shi A, Zong H, et al. Randomized trial of electrodynamic microneedle combined with 5% minoxidil topical solution for the treatment of Chinese male androgenetic alopecia. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2020;22(1):1–7. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2017.1376094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah KB, Shah AN, Solanki RB, Raval RC. A comparative study of microneedling with platelet-rich plasma plus topical minoxidil (5%) and topical minoxidil (5%) alone in androgenetic alopecia. Int J Trichol. 2017;9(1):14–18. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_75_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YB, Eun YS, Lee JH, Cheon MS, Park YG, Cho BK, et al. Effects of topical application of growth factors followed by microneedle therapy in women with female pattern hair loss: a pilot study. J Dermatol. 2013;40(1):81–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aboeldahab S, Nada EEA, Assaf HA, Gouda ZA, Abu El-Hamd M. Superficial cryotherapy using dimethyl ether and propane mixture versus microneedling in the treatment of alopecia areata: a prospective single-blinded randomized clinical trial. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(5):e15044. doi: 10.1111/dth.15044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ragab SEM, Nassar SO, Morad HA, Hegab DS. Platelet-rich plasma in alopecia areata: intradermal injection versus topical application with transepidermal delivery via either fractional carbon dioxide laser or microneedling. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2020;29(4):169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdallah MAE, Shareef R, Soltan MY. Efficacy of intradermal minoxidil 5% injections for treatment of patchy non-severe alopecia areata. J Dermatol Treat. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1793893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giorgio CM, Babino G, Caccavale S, Russo T, De Rosa AB, Alfano R, et al. Combination of photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolaevulinic acid and microneedling in the treatment of alopecia areata resistant to conventional therapies: our experience with 41 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45(3):323–326. doi: 10.1111/ced.14084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo KH, Lee JW, Li K, Kim BJ, Kim MN. Photodynamic therapy with methyl 5-aminolevulinate acid might be ineffective in recalcitrant alopecia totalis regardless of using a microneedle roller to increase skin penetration. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(5):618–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inui S, Fukuzato Y, Nakajima T, Yoshikawa K, Itami S. Androgen-inducible TGF-beta1 from balding dermal papilla cells inhibits epithelial cell growth: a clue to understand paradoxical effects of androgen on human hair growth. FASEB J. 2002;16(14):1967–1969. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0043fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inui S, Fukuzato Y, Nakajima T, Yoshikawa K, Itami S. Identification of androgen-inducible TGF-β1 derived from dermal papilla cells as a key mediator in androgenetic alopecia. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2003;8(1):69–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winiarska A, Mandt N, Kamp H, Hossini A, Seltmann H, Zouboulis CC, et al. Effect of 5α-dihydrotestosterone and testosterone on apoptosis in human dermal papilla cells. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;19(6):311–321. doi: 10.1159/000095251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lolli F, Pallotti F, Rossi A, Fortuna MC, Caro G, Lenzi A, et al. Androgenetic alopecia: a review. Endocrine. 2017;57(1):9–17. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1280-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.English R, Ruiz S. Conflicting reports regarding the histopathological features of androgenic alopecia: Are biopsy location, hair diameter diversity, and relative hair follicle miniaturization partly to blame? Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:357–365. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S306157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta AK, Quinlan EM, Venkataraman M, Bamimore MA. Microneedling for hair loss. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jocd.14525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alster TS, Li MKY. Microneedling of scars: a large prospective study with long-term follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(2):358–364. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000006462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El-Domyati M, Barakat M, Awad S, Medhat W, El-Fakahany H, Farag H. Microneedling therapy for atrophic acne scars: an objective evaluation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8(7):36–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henry S, McAllister DV, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR. Microfabricated microneedles: a novel approach to transdermal drug delivery. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87(8):922–925. doi: 10.1021/js980042+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goren A, Castano JA, McCoy J, Bermudez F, Lotti T. Novel enzymatic assay predicts minoxidil response in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27(3):171–173. doi: 10.1111/dth.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jimenez F, Izeta A, Poblet E. Morphometric analysis of the human scalp hair follicle: practical implications for the hair transplant surgeon and hair regeneration studies. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(1):58–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sasaki GH. Micro-needling depth penetration, presence of pigment particles, and fluorescein-stained platelets: clinical usage for aesthetic concerns. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(1):71–83. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lima EVdA, Lima MdA, Takano D. Microneedling: experimental study and classification of the resulting injury. Surg Cosmet Dermatol; 2013;110–114.

- 46.Fernandes D. Commentary on: micro-needling depth penetration, presence of pigment particles, and fluorescein-stained platelets: clinical usage for aesthetic concerns. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(1):86–88. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Randall VA, Ebling FJ. Seasonal changes in human hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124(2):146–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trüeb RM. Telogen effluvium: Is there a need for a new classification? Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2(1–2):39–44. doi: 10.1159/000446119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.