Abstract

This cross-sectional study uses Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality data to compare incidence of cervical cancer in the lowest–socioeconomic status neighborhoods with that in higher–socioeconomic status neighborhoods of New York City from 2012 through 2016.

Cervical cancer is preventable, and the risk of developing the disease has been linked to accessibility of preventive services.1 In the United States, access to health care services is linked to socioeconomic status (SES) and has been implicated in contributing to health disparities.2 New York, the US’s most densely populated major city, exhibits significant racial and socioeconomic inequities.3 This study sought to quantify the association between neighborhood SES and the incidence of cervical cancer in New York City.

Methods

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study of women residing in New York City from 2012 through 2016. We abstracted cases of cervical cancer and age-standardized incidence rates by New York City neighborhood (as defined in the Public Use Microdata Areas of the 2010 decennial census) from the New York State Cancer Registry and linked these with self-reported neighborhood-level data from the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. This study was exempted from informed consent and review by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board. The data analysis was performed from July 1 to October 16, 2020. We calculated an SES index for each neighborhood by using a weighted combination of measures of crowding, real-estate values, poverty rates, incomes, educational attainment, and unemployment, developed and validated by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.4 We fitted a Poisson regression model with robust SEs to estimate the association between cervical cancer incidence and neighborhood SES index, modeling SES as a continuous variable. We estimated neighborhood cancer incidence rates and rate ratios (and corresponding 95% CIs, for which 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant) associated with residence in lowest-SES neighborhoods (10th percentile) compared with highest-SES neighborhoods (90th percentile). Data analysis was performed using Stata, version 16 (StataCorp LLC) and RStudio, version 1.3.1073 (RStudio).

Results

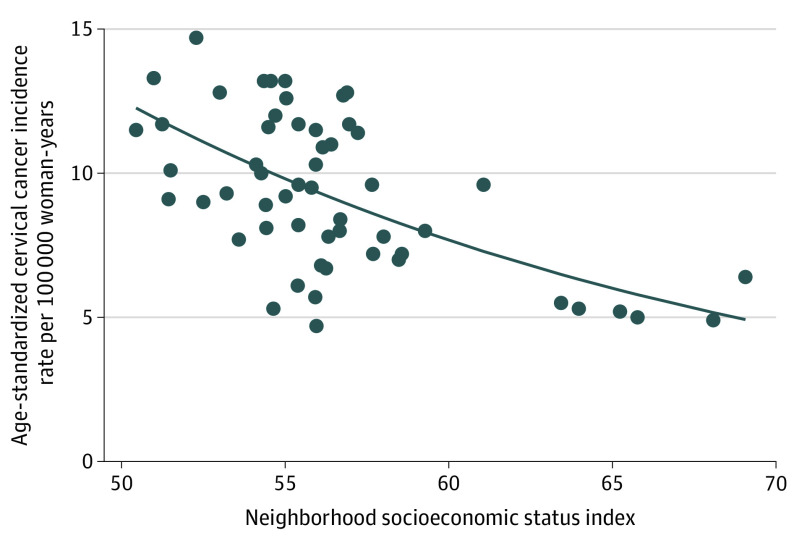

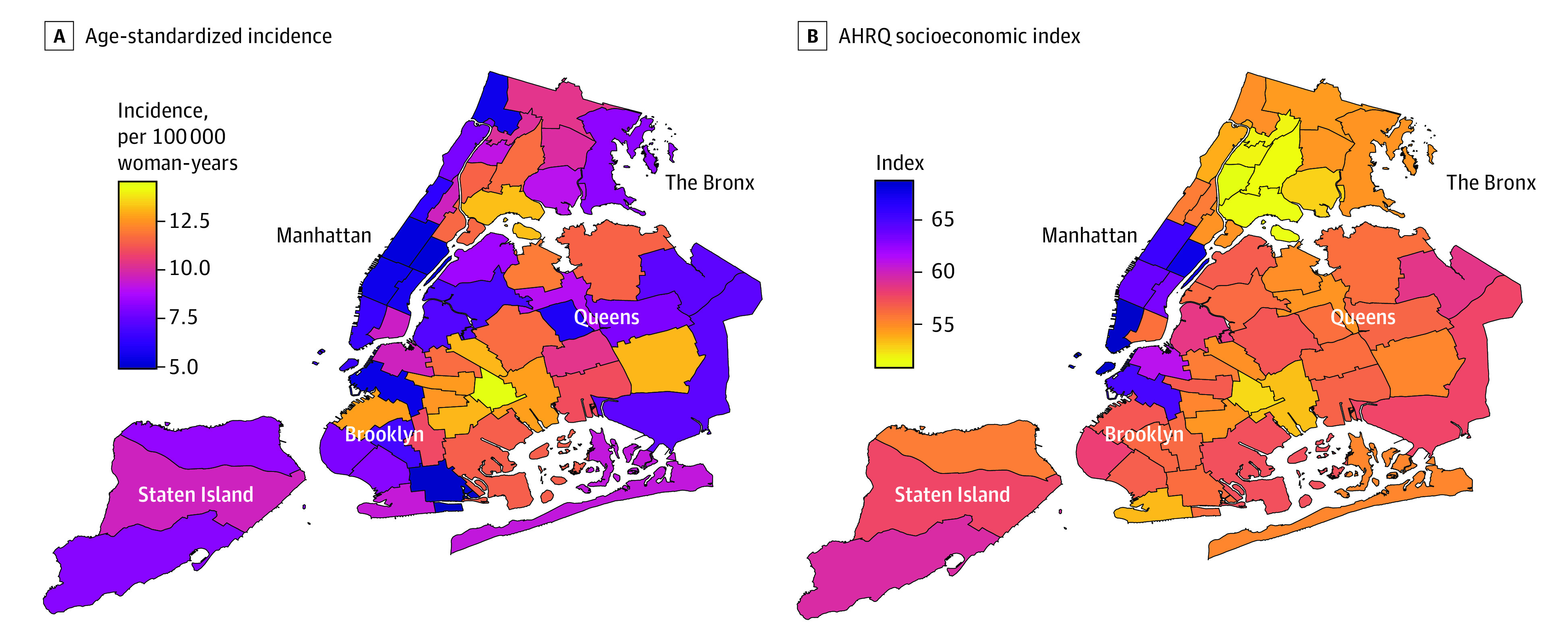

There were 932 cases of cervical cancer diagnosed in 55 New York City neighborhoods from January 1, 2012, through December 31, 2016, corresponding to an age-standardized incidence rate of 9.1 cases per 100 000 woman-years (95% CI, 8.7-9.5 cases per 100 000 woman-years). Age-standardized cervical cancer incidence rates varied across neighborhoods, ranging from 4.4 (95% CI, 2.9-7.4) to 14.7 (95% CI, 10.8-19.5) cases per 100 000 woman-years. We identified substantial variation in self-reported socioeconomic and demographic factors among neighborhoods. Neighborhoods with the highest SES index values (top decile) were predominately populated by White residents (68.9%), with fewer Hispanic (11.6%) or Black (4.5%) residents. Conversely, bottom-decile SES neighborhoods were principally populated by Hispanic (60.1%) and Black (33.5%) residents and fewer White residents (3.0%). Neighborhood SES index was strongly associated with cervical cancer incidence (Figure 1): after age-standardization, women residing in the lowest-SES neighborhoods were 73% more likely to develop cervical cancer than those in the highest-SES neighborhoods (interdecile incidence rate ratio, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.52-1.96; P < .001), corresponding to incidence rates of 11.2 (95% CI, 10.3-12.2) and 6.5 (95% CI, 5.9-7.1) cases per 100 000 woman-years, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Maps of Cervical Cancer Incidence and Socioeconomic Status in New York City’s Neighborhoods.

Heat maps of New York City neighborhoods show the age-standardized cervical cancer incidence rates (per 100 000 woman-years) (A) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Socioeconomic Index (B) by neighborhood in New York City.

Figure 2. Association Between Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and Cervical Cancer Rates.

Each point corresponds to a neighborhood, and the line is the estimated age-standardized cervical cancer rate from a bivariable Poisson regression model.

Discussion

In this population-based, cross-sectional study, we found that New York’s lowest-SES neighborhoods, populated predominantly by Black and Hispanic residents, had cervical cancer incidence rates 73% higher than the mostly White populations of the city’s highest-SES neighborhoods. The magnitude of this disparity exceeds those associated with Black race, Hispanic ethnicity, or residence in a rural county in a population-based study of the US.5 The existence of this disparity among persons living in proximity highlights the need to implement targeted neighborhood-level interventions to increase access to, and utilization of, preventive services, including vaccination and screening. Interventions that leverage social determinants of health, including neighborhood and built environment, social/community support systems, education, economic stability, and health care access, to increase cancer screening in vulnerable populations, have been shown to be cost-effective.6

This study has some limitations. Because this was a cross-sectional study, it cannot establish a causal link between neighborhood SES and cervical cancer incidence. Further, since this study relied on a neighborhood-level measure of SES, these data cannot be used to quantify person-level associations between SES and cervical cancer risk. Nevertheless, the findings of this study suggest that scalable, evidence-based interventions that incorporate community and sociocultural context may be especially important to promoting prevention, vaccination, and early detection and to reduce disparities in diverse urban centers with large immigrant populations.

References

- 1.Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, et al. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1340-1348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1917338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer PA, Penman-Aguilar A, Campbell VA, Graffunder C, O’Connor AE, Yoon PW; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Conclusion and future directions: CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report—United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl. 2013;62(3):184-186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karpati A, Kerker B, Mostashari F, et al. Health Disparities in New York City. New York City Dept of Health & Mental Hygiene; 2004. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_other_2004_jul_health_disparities_in_new_york_city_karpati_disparities_pdf.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonito AJ, Bann C, Eicheldinger C, Carpenter L. Creation of New Race-Ethnicity Codes and Socioeconomic Status (SES) Indicators for Medicare Beneficiaries: Final Report, Sub-Task 2. Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality; 2008. AHRQ Publication 08-0029-EF. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu L, Sabatino SA, White MC. Rural-urban and racial/ethnic disparities in invasive cervical cancer incidence in the United States, 2010-2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E70. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohan G, Chattopadhyay S. Cost-effectiveness of leveraging social determinants of health to improve breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(9):1434-1444. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]